11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

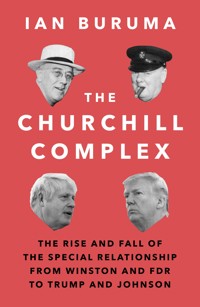

It is impossible to understand the last 75 years of British and American history without understanding the Anglo-American relationship, and specifically the bonds between presidents and prime ministers. FDR of course had Churchill; JFK famously had Macmillan, his consigliere during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Reagan found his ideological soul mate in Thatcher, and George W. Bush found his fellow believer, in religion and in war, in Tony Blair. In a series of shrewd and absorbing character studies, Ian Buruma takes the reader on a journey through the special relationship via the fateful bonds between president and prime minister. It's never been a relationship of equals: from Churchill's desperate cajoling and conniving to keep FDR on side, British prime ministers have put much more stock in the relationship than their US counterparts did. For Britain, resigned to the loss of its once-great empire, its close kinship to the world's greatest superpower would give it continued relevance, and serve as leverage to keep continental Europe in its place. As Buruma shows, this was almost always fool's gold. And now, as the links between the Brexit vote and the 2016 US election are coming into sharper focus, it is impossible to understand the populist uprising in either country without reference to Trump and Boris Johnson, though ironically, they are also the key, Buruma argues, to understanding the special relationship's demise.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE CHURCHILL COMPLEX

Also by Ian Buruma

A Tokyo Romance: A Memoir

Their Promised Land: My Grandparents in Love and War

Theater of Cruelty: Art, Film, and the Shadows of War

Year Zero: A History of 1945

Taming the Gods: Religion and Democracy on Three Continents

The China Lover: A Novel

Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

Inventing Japan: 1853–1964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Playing the Game: A Novel

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers, Transvestites, Gangsters, Drifters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo (text by Donald Richie; photographs by Ian Buruma)

This edition published by arrangement with Penguin Press,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Ian Buruma, 2020

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Book design by Amanda Dewey

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-465-8

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-466-5

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-467-2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For John Ryle

CONTENTS

One• UNDER THE SIGN OF VICTORY

Two• BLOOD AND HISTORY

Three• THE EMPIRE IS DEAD, LONG LIVE THE EMPIRE

Four• THE ROAD TO SUEZ

Five• AN ANGLO-AMERICAN BOND

Six• THE CLOSE RELATIONSHIP

Seven• TO EUROPE AND BACK

Eight• AN EXTRAORDINARY RELATIONSHIP

Nine• KINDER, GENTLER

Ten• TOO MUCH CONVICTION

Eleven• THE FINEST MOMENT

Twelve• AFTER THE CRASH

Thirteen• GRAND ILLUSIONS

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

One

UNDER THE SIGN OF VICTORY

It seems to me that God, with infinite wisdom and skill, is

training the Anglo-Saxon race for an hour sure to come . . .1

· REV. JOSIAH STRONG, 1885

When the war is over we shall live in an Anglo-American world.

There will be other great powers, but the sanctions on which the

West reposes will be the ideas for which England and America

have fought and won, and the machines behind them.

· CYRIL CONNOLLY

I saw Winston Churchill. On my seventh birthday, in 1958. My grandparents took my younger sister and me to see Peter Pan at the Scala Theatre in London. When she wasn’t too drunk to perform, Sarah Churchill played Peter. Quite often she played Peter while drunk as well. Once, she audibly said “Fuck!” when she landed awkwardly after flying across the stage unsteadily on a wire.

Nothing like that happened on the afternoon we attended the play. Or if it did, I can’t remember. What I do recall is the moment Sarah’s father arrived. The memory is a kind of audiovisual blur: a pale face in the spotlight, a pudgy hand emerging from a fur muff to make the V sign, and everyone around me, including my very patriotic British grandparents, breaking into wild applause. (The fur muff is a detail I know only from the photograph published in the papers the next day.) Being Jewish, my grandparents felt strongly that Churchill had saved their lives. The extraordinary enthusiasm of that moment, the shining eyes and the raucous cheering for an old man in a theater box, has stayed with me; it was a bit like watching adults behave like rowdy children, which fitted the story of Peter Pan in a way, the boy who never grew up.

I must have had only a very vague idea who Churchill was. But reminders of the war were still around us: waterlogged bomb craters all over London, drunken soldiers from the British Rhine army throwing up on the ferry from the Hook of Holland to Harwich, and a steady diet of British comic books featuring dashing Spitfire pilots and beastly Germans. At home in The Hague, where I was born to a Dutch father, I assembled plastic Airfix models of Lancaster bombers. And British people we would meet at family parties in England still spoke to foreigners with the polite condescension that those who had lived through their finest hour still reserved for those who had been defeated.

Recent history was experienced by people of my age—I was born just six years after the war—largely as myth, in which Churchill played an important part. We were allowed a day off school to watch his funeral in black-and-white on television. This was just another reminder that we had been liberated from the Germans by people who spoke English. Canadians finished the job in the early spring of 1945, but American and British troops, as well as Canadians, had already entered the country from the south in 1944 and were dropped in the autumn of the same year along the Rhine in the disastrous Battle of Arnhem. Polish troops had played a heroic part, too, but this was not widely known. The language of freedom was English. Canadian troops were billeted in my paternal grandparents’ house in Nijmegen, near Arnhem. The women danced with their liberators to Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.” Hershey bars and silk stockings were liberally distributed in return for favors, which in many cases might have been granted anyway. And it was never forgotten that in the “hunger winter” of 1944–45, British and American bombers dropped onto a starving population bags of flour, corned beef, margarine, and chewing gum.

My own perception of Europe’s liberation, like that of most people of my age, was largely shaped by the movies. Some of the most powerful cinematic memories bear little relation to artistic quality, or indeed historical accuracy. I still cannot watch The Longest Day, Darryl Zanuck’s Hollywood reenactment of the D-Day landings, without weeping. All the Anglo-American stereotypes are there: Robert Mitchum, the macho Yankee chomping on a cigar while leading his men onto Omaha Beach; Sean Connery as a plucky Scottish private; Peter Lawford as Lord Lovat, accompanied by his own bagpiper—the very idea of a bagpiper playing under German fire is enough to reduce me to tears; John Wayne, dropped from the sky over Normandy to sort things out; and Kenneth More, the unflappable Royal Navy captain wading through the surf with his bulldog named Winston.

If the ghost of Churchill hovered around my childhood in The Hague, its presence was felt even more keenly in Washington, DC, and it lingered far longer. Presidents from John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush and beyond have hoped to follow the great war leader’s example and save the world for democracy. His was the heroic myth they felt they had to live up to.

So tenacious has the aura of Churchill been that a political row erupted in 2016 over his bust in the Oval Office when Donald Trump was about to move in. Trump’s people placed a bust of Churchill in the office with great fanfare, claiming that President Obama had replaced it with a bust of Martin Luther King Jr. Boris Johnson—the British politician who expressed warm feelings for Trump, wrote a shallow hagiography of Winston Churchill, encouraging flattering comparisons to the author, and would later become prime minister—attributed this “swap” to “an ancestral dislike of the British Empire.”2 In fact, the sculpture that Obama replaced had been loaned to George W. Bush by Tony Blair, while an older bust of Churchill, once given by Britain to Lyndon B. Johnson, was being repaired. Obama quite properly gave the new bust back once the old one was restored. Now the old bust perches behind the desk of Trump, whose scowl might be mistaken for an attempted impersonation of Churchillian gravitas.

Churchill the man has been more popular in the US than his country ever was. Even presidents who had little time for the British revered Churchill. There are several possible reasons for this. Churchill’s own (belated) sentimental feelings for the native country of his beloved mother, Jennie Jerome from Brooklyn, New York, were often expressed in flowery speeches all over the US. His frequent references to “the English-speaking peoples” and Anglo-Saxon “kith and kin” no doubt appealed to Americans of a certain age and class. But Churchill’s main attraction, I believe, lies in the same myth that colored my childhood, which ties in closely to the view many Americans have of themselves: the beacon of liberty, the city on the hill, the land of the brave, the exceptional nation that freed the world from dictators. Churchill, although only half-American, became the symbol of this defiance of tyranny. He is the bulldog face of Anglo-American notions of valor.

Another ghost haunts Washington, DC, as well as London, along with Churchill’s. Indeed the two are intimately linked. That is the ghost of Munich, the city where the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain signed an agreement with Hitler in September 1938 that allowed Germany to take a chunk of Czechoslovakia with impunity. Chamberlain thought he had bought “peace for our time.” Churchill, speaking in Parliament, called it a “total and unmitigated defeat.” He thought this “bitter cup” could be averted only once Britain recovered its “moral health and martial vigor” and arose again to take a “stand for freedom as in the olden time.”

It is possible, as some maintain, that if Britain and France had taken that stand in 1938, Hitler’s ambition of conquering Europe would have been thwarted. Others continue to argue that Chamberlain had no choice, since Britain was not ready to fight a war against Germany, and the US was in no mind to get involved. But the mythical verdict, still repeated in political speeches, and celebrated in the movies, is that Chamberlain was a shortsighted and cowardly appeaser and Churchill the hero. Ever since, whenever a foreign crisis has loomed, from the Suez Canal to the Korean peninsula, from Vietnam to the Falkland Islands, and from Bosnia to Iraq, the specter of Munich is invoked by Anglo-American leaders who want to go down in history as Churchill, not Chamberlain.

Churchill is often credited with coining the phrase “Special Relationship.” He certainly made it popular, if only to convince the Americans to come to Britain’s rescue in the perilous early years of World War II. Since then, despite Churchill’s mythical spirit living on in the White House, the Anglo-American relationship has been more special in London than in Washington. Given the growing gap in relative power and influence between the two countries, this was inevitable. Indeed, as Britain’s power waned, clinging to the Special Relationship was one way for the British to maintain an illusion that the glow of its finest hours under Roosevelt and Churchill had not been totally extinguished. British leaders might have been reduced to playing a steadily diminishing and sometimes demeaning role of impoverished but worldly-wise Greeks in the American Rome, but in their own eyes at least, this still allowed them to sup at a higher table than the other Europeans.

Britain’s tortured relationship with the European continent, resulting at this time of writing in acrimonious wrangling over Brexit, is partly the result of Britain’s nostalgia for the Special Relationship. Churchill himself spoke out in favor of a united Europe in 1946, even though he was vague about Britain’s participation, but his spirit has made it harder for Britain to regard itself as a European nation on par with Germany or France, and to find its proper place in common European political and financial institutions.

There are many ways to chronicle the Special Relationship between Britain and the United States since they joined forces in World War II. One would be to examine the history of close cooperation between the British and American intelligence agencies. Another would be to describe the building of international financial institutions, such as the IMF and the World Bank. One of the promises made by Churchill and Roosevelt in their Atlantic Charter of 1941 was “global economic cooperation.” Defeating Hitler, fascism, and the Japanese Empire was an internationalist enterprise. The postwar order, solidified in the Cold War, was set up by Britain and the US to defend democracies against their despotic enemies. If an anti-Communist despot was supported nonetheless, as long as he served Anglo-American interests, this was generally regarded in Washington and London as a necessary form of hypocrisy.

However, this book is not a history of institutions. I have chosen to write about the evolution and erosion of an idea, the Anglo-American myth that I grew up with. All US and British leaders have been touched by the history of World War II, even those who were not yet born when Roosevelt and Churchill drew up the Atlantic Charter. The story of those leaders and how they related to one another is also the story of their respective countries and how they affected the rest of the world, west as well as east.

It is my view that the shared myth has been both magnificent and a curse. History can inspire but also bedevil. How a wartime alliance that defeated Hitler, with the indispensable help of Stalin’s Red Army, ended up after more than half a century of peace and prosperity in the West in the dispiriting and dangerous bluster and self-delusion of Trump and Brexit, is a melancholy tale. Britain and the US, despite all their flaws, were once regarded as models of openness, liberalism, and generosity. Even if they by no means always lived up to these ideals, the two English-speaking nations still offered some hope for what the Hungarian-born writer Arthur Koestler once called “the internally bruised veterans of the totalitarian age.”

Now, perhaps only for the time being, the internationalist ideals set out in the Atlantic Charter have made way for populist agitation against immigrants, a hugely destructive British divorce from Europe, and an American president whose greatest wish is to build a big wall to keep the tired, poor, huddled masses from entering the US. Enoch Powell, a British Tory politician who held many reprehensible views, said once, quite wisely, that all political lives end in failure, “for that is the nature of politics and human affairs.” The same might be said of the hopes of once great nations. That doesn’t make those hopes any less admirable.

Two

BLOOD AND HISTORY

Let not England forget her precedence of teaching nations how to live.

· JOHN MILTON (TO PARLIAMENT)

Before World War II, there was not much love lost between the British and Americans. Few people had the means to travel across the Atlantic. Historic wounds—the Boston Tea Party, wars of independence, 1812—were, if not fresh, still remembered in America. True, the US had joined the Allies in World War I in 1917 as an “associated power,” and left more than fifty thousand dead on European soil (another sixty thousand died of disease, most because of the flu epidemic in 1918). But German and Irish Americans, and quite a few other “hyphenated” citizens not of British stock, had reason to be bitter about being made to feel like suspect outsiders in their own country. The great American journalist H. L. Mencken, who still spoke German with his parents, was so bruised by this experience that he later refused to see the conflict with Hitler’s Germany as anything but “Roosevelt’s war.”

American Anglophilia existed, of course, but as in Europe, it was mostly a form of snobbery, a kind of mimicry of upper-class manners, popular among East Coast elites, the kind of people who sent their sons to English-style boarding schools and later to the pseudo-Gothickry of Ivy League universities. In his History of the American People (1902), Woodrow Wilson, a Southerner of Scots-Irish extraction, and the man responsible for getting his country into the European war, extolled the special virtues of “the self-helping race of Englishmen.”1 This splendid race, he enthused, having outsmarted the wily French, provided the necessary backbone to the New World. In 1918, after the war was won, Wilson was stung by domestic criticisms that he had been too easily swayed by British interests. And so, at a victory banquet given to him at Buckingham Palace by King George V, he tempered his earlier sentiments: “You must not speak of us who come over here as cousins, still less as brothers; we are neither. Neither must you think of us as Anglo-Saxons, for that term can no longer be rightly applied to the people of the United States.”2

When the British in 1940 and ’41, desperate for American help in a war that threatened to overwhelm them, used their finest rhetoric about common values, the shared English language, and the Anglo-American love of freedom, most Americans refused to be drawn in. Many were wary of being outwitted by the silver-tongued British, and suspicious that Britain was fighting selfishly to preserve its empire, for which few Americans felt any affection. In late 1941, General George Marshall, chief of staff, was still not keen to give the British all they wanted. But even he felt that there was “too much anti-British feeling” among his military colleagues—“Our people were always ready to find Albion perfidious.”3

But many of the British grandees sent out to solicit US help didn’t like the Americans much either. When Lord Halifax took up his post as ambassador to Washington in December 1940, he wrote to the former prime minister Stanley Baldwin: “I have never liked Americans, except odd ones. In the mass I have always found them dreadful.” Lord Linlithgow, the bungling viceroy of India, the man who would make the horrendous Bengal famine of 1943 so much worse, commiserated: “The heavy labour of toadying to your pack of pole-squatting parvenus! What a country, and what savages those who inhabit it!”4 John Maynard Keynes was dispatched to Washington in 1917 to secure loans for the British war effort. His impression: “The only really sympathetic and original thing in America is the niggers, who are charming.”5

Winston Churchill made a great deal of his friendship with Roosevelt, which he regarded as the cornerstone of the Special Relationship: “I wooed Roosevelt more ardently than a young man woos a maiden.” But he was often scathing about America in private conversations. In 1928, at a dinner party in his home, he said that the US was “arrogant, fundamentally hostile to us, and [wishing] to dominate world politics.”6 When Roosevelt first met Churchill in 1918, at a dinner in London, he didn’t care for him at all. Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the navy, found Churchill, who was minister of munitions, an intolerable snob. Churchill, in Roosevelt’s recollection, had “acted like a stinker . . . lording it all over us.”7 When the two leaders met again in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, in 1941, Churchill had entirely forgotten their first encounter. Roosevelt had not.

Roosevelt, despite his quasi-aristocratic airs, was never an Anglophile. If anything, he was rather proud of his Dutch ancestry. Like most Americans, he had little time for European colonial empires, but he is said to have made an exception for the Dutch East Indies, even though the Dutch probably behaved worse toward their colonial subjects than the British did. So references to Anglo-Saxon roots and shared bloodlines failed to move the American president’s cool and calculating heart.

Churchill, on the other hand, talked about his bloodlines a great deal, and not just out of wartime necessity. Receiving an honorary degree at Harvard in 1943, he told his admiring audience, “You will find in the British Commonwealth and Empire good comrades to whom you are united by other ties besides those of state policy and public need. To a large extent they are the ties of blood and history. Naturally I, a child of both worlds, am conscious of these.”8

Historians have claimed that Churchill invented the Special Relationship as a necessary move to win the war. This is true, up to a point. The Anglo-American alliance might never have been forged if France were not overrun in the spring of 1940. But Churchill only made the term famous six years later, in his speech at Fulton, Missouri, when he urged the Americans to stand firm against Communism and continue the “fraternal association of the English-speaking peoples.” He insisted upon the “Special Relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.” To Churchill the idea of the English-speaking peoples, of transatlantic kith and kin, was more than an expedient strategy; it defined him as a man. His relationship with the US was a personal twist on a romantic idea that long preceded him.

Before he died in 1902, Cecil Rhodes established a scholarship at Oxford University for students from the US and the British Empire to nurture a common idea of empire and cement “the union of the English-speaking peoples throughout the world.” This matched the imperial sentiments of Rudyard Kipling, who sent his poem The White Man’s Burden (“Take up the white man’s burden—/Send forth the best ye breed . . .”) to Theodore Roosevelt in 1899, then governor of New York, to encourage the Americans to bring Anglo-American enlightenment to the conquered Filipinos—“Your new caught sullen peoples,/Half devil and half child.”

In that same year, when the British were trying to subdue the Boers in South Africa, Joseph Chamberlain, who was prime minister as well as foreign secretary, called for a “new triple alliance between the Teutonic race and the two great branches of the Anglo-Saxon race.” On the other side of the Atlantic, Theodore Roosevelt’s supporter Albert J. Beveridge, a “progressive” senator from Indiana, exclaimed, “God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-admiration. No! He has made us the master-organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns.”9

So the idea that the Anglo-Saxon races were called upon to subdue barbarians and order the world was already current when Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt were still children. It was the kind of thinking that justified colonial rule and resulted in some of Churchill’s worst traits, such as his contempt for the people of India. (“I hate Indians. They are a beastly people with a beastly religion.”) The inclusion of the “Teutons” in this line of thought might suggest a kind of crypto-Nazism, which would be highly ironic considering the history of the two world wars.

In fact, there actually was more than a hint of this. One of the intellectual fathers of nineteenth-century Anglo-Saxonism was the historian and politician Edward Augustus Freeman, famous for his History of the Norman Conquest. His approval of the US was unusual for an Englishman of his time. And he was clearly a racist. Benjamin Disraeli was, in his view, “a dirty Jew.” Freeman condoned Russian pogroms, and anti-Chinese riots in California too. After all, he thought, these were “only the natural instinct of any decent nation to get rid of filthy strangers.”10

And yet, Freeman was not a conservative, but a liberal supporter of William Gladstone. The notion that Anglo-Saxons and Teutons were a superior breed was not so much based on bloodlines as on the claim to a unique love of liberty. This is something that appealed to German romantics as well, the ancient Teutonic spirit of freedom, expressed in German literature, but also, so some Germans claimed, in Rembrandt’s paintings and Shakespeare’s plays, the “Nordic” greatness of which, they believed, emerged only in German translation. But the idea goes back much further than the age of the great bard. Here is Freeman again, on the victory in 9 AD over the Roman army by a Germanic tribe led by Arminius: “Arminius ‘liberator Germaniae,’ is but the first of a roll call which goes on to Hampden and Washington.”

John Hampden, one of Churchill’s heroes, was a politician who fought with the Ironsides in the English Civil War for parliamentary rule and against the absolute power of the king. He was killed in battle in 1643. His, or for that matter George Washington’s, link to Arminius is tenuous at best, but it made for a peculiar political conceit.

The name left unmentioned in this pantheon of liberty is that of Pericles, who lived long before the Angles, the Saxons, or the Teutons had even been heard of. But his oration about the exceptional nature of Athens, spoken in 431 BC, after the first battle of the Peloponnesian War, could be read as a kind of blueprint for Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism. He spoke of the laws that afforded equal justice to all men, and of the “freedom we enjoy in our government.” The people of Athens, like the imagined English-speaking peoples more recently, “dwelt in the country without break in the succession from generation to generation, and handed it down free to the present time by their valor.”

The concept of the English-speaking peoples now has an imperialist ring, promoted in our time by certain conservative historians. Churchill himself told the Americans at Fulton that “70 or 80 millions of Britons spread about the world” (meaning Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa) stood ready to defend “our traditions and our way of life.” What he really meant was spelled out more clearly in a letter to Eisenhower in 1953: “Britain with her eighty million white English-speaking people.”11 But the origins of the term are less blimpish.

During the American Civil War, the main British political parties, as well as much of the upper class, supported the Confederacy. Radical leaders, however, such as Richard Cobden and John Bright, supported the antislavery cause of the North. Their vision of the English-speaking peoples was one of working-class solidarity against the landowning classes in both countries. William E. Forster, a Liberal politician in Gladstone’s government, gave his name to what his boss called “Forsterism”: the idea that Anglo-American Protestants were called by God to spread democracy to the world’s benighted peoples. It was Forster, Cobden, and Bright who first promoted the idea of the common, freethinking, democratic English-speaking peoples, as opposed to the autocratic upper classes from which Churchill sprang.

The radical cause was not something one would associate with Churchill anyway. And he had such a limited interest in Anglo-Saxonism that he poured cold water over a pet project of his adored mother, an expensive magazine called The Anglo-Saxon Review. But the Whiggish conceit that the love of freedom was the birthright of English speakers stretching back, if not to the Teutonic rebellion against Rome then at least to King Alfred, was certainly part of his makeup. Churchill brought this up on some unexpected occasions. When Joseph Chamberlain wanted to strengthen the imperial economy by erecting a tariff wall around British possessions, Churchill rebelled and made a plea for free trade. “The strength and splendour of our authority,” he declaimed, “is derived not from physical forces, but from moral ascendency, liberty, justice, English tolerance, and English honesty.”12

None of this would have impressed Franklin D. Roosevelt. And yet, despite his earlier misgivings about the British politician, Roosevelt sought Churchill out in 1939, a little over a week after Britain had declared war against Germany. Churchill was first lord of the Admiralty then. The letter, addressed to “My Dear Churchill,” expressed Roosevelt’s wish to be kept “in touch personally with anything you want me to know about.” This was an unusual request for a US president to make of a mere British cabinet minister. But the president told his ambassador in London, the egregiously Anglophobic Joseph Kennedy, that Churchill was likely to become prime minister, so Roosevelt wanted “to get my hand in now.”13

Apart from a flair for aristocratic affectations—the long cigarette holder, the cigar, the top hats—the two consummate political showmen had one important thing in common: a romance with the sea, and thus with naval matters. In Churchill’s letters to Roosevelt, he referred to himself as “Naval Person,” and after he became prime minister as “Former Naval Person.” Roosevelt was a keen student of Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan’s books, and had corresponded with the author. In his book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, written in 1890, Mahan explains how British greatness was due to their mastery of the seas. Like the Dutch, who conquered the seas before, this had to do in Mahan’s view with a natural instinct for trade, which, he argued, stemmed from geography, culture, politics, religion, and race. (The English and the Dutch, he claimed, were “radically of the same race.”)14 A bit oddly for an American, Mahan had good things to say about colonialism too: “In yet another way does the national genius affect the growth of sea power in its broadest sense; and that is in so far as it possesses the capacity for planting healthy colonies.”15 The US, he thought, should emulate Britain, if not in planting colonies, then certainly in asserting power over the seas, in “a cordial understanding” with Great Britain, since both nations “are controlled by a sense of law and justice, drawn from the same sources, and deep-rooted in [their] instincts.”16

Carl Schmitt commented on Mahan, rather favorably, in his book Land and Sea, published in 1942. Schmitt was a German legal theorist who joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and provided legal justifications for Hitler’s dictatorship. His argument in Land and Sea is that Mahan was right: Britain and the US had owed their immense power to ruling the seas, the result of a typically Protestant entrepreneurial spirit. Catholic powers, he believed, were more land bound. What Mahan had not foreseen, Schmitt argued, was that sea power had become obsolete in the machine age, where airplanes had “lifted man high above the plains and the waves.”

Roosevelt might not have gone that far, but he did take Schmitt’s point. In his State of the Union address in 1940, he acknowledged that most Americans did not want to send their boys to fight in Europe a second time. But he also made it plain that in an age of modern aircraft and long-range battleships, the US could not survive “as a self-contained unit . . . inside a high wall of isolation, while outside the rest of Civilization and the commerce and culture of mankind are shattered.” The US government would insist that military actions be banned within a three-hundred-mile zone of the US coast. Naval Person answered Roosevelt’s letter of 1939 with the promise that “we wish to help you in every way in keeping the war out of American waters.”

But of course Churchill wanted much more than that. He knew that Germany could not be defeated without full American participation in the war. The problem was that despite Roosevelt’s opposition to the isolationists, there was not nearly enough political will to comply. Many Americans, including Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, were convinced in 1940 that Britain was losing the war, and didn’t see why they should fight for British interests anyway. Roosevelt was also keenly aware of Woodrow Wilson’s failure in 1919 to get the Senate to back his foreign commitments, specifically his attempt to build a new world order through the League of Nations. The world order, although something very much on the president’s mind, was not of great concern to most Americans.

Within weeks of becoming prime minister on May 10, 1940, Churchill begged the Americans to intervene when France was buckling to the German Blitzkrieg. They did not. He asked for American destroyers to be sent across the Atlantic. The defense of Britain, he said, depended on it. It was “the only hope of averting the collapse of civilization.”17 To keep up British morale at a very bleak time, and perhaps to boost his own as well, Churchill remained optimistic that the Americans would soon change their minds and come in. A collection of Churchill’s prewar speeches, entitled Blood, Sweat and Tears, was published in the US with the express purpose of convincing Americans to come to the rescue. One of these speeches had been made on American radio in October 1938: “If ever there was a time when men and women who cherish the ideals of the founders of the British and American Constitutions should take earnest counsel with one another, this time is now.”18

This bit of rhetoric, too, drew on old ideas about Anglo-American communalities. Not race, or language, but political institutions were the glue that held the English speakers together. Churchill, and others, liked to draw a straight line from the Magna Carta to the Declaration of Independence. Speaking on the Fourth of July, 1918, he claimed that a “similar harmony exists between the principles of that Declaration and all that the British people have wished to stand for, and have in fact achieved at last both here at home and in the self-governing Dominions of the Crown.”19 He tactfully omitted to say that it was American independence from the Crown that was being celebrated on that day.

There were no doubt Americans who were susceptible to this kind of talk. Churchill’s wartime speeches were widely broadcast in the US. Roosevelt was, however, too worried about public opinion to be so easily swayed. But the US could still benefit from British distress. Roosevelt agreed in 1940 to lend fifty old destroyers in exchange for the right to use British bases in Newfoundland and the Caribbean. It was, in Roosevelt’s own words, “a ‘deal’—and very successful from our trading point of view.”20

The ships were in poor shape and took some time to become operational. Guns, tanks, and planes were also shipped over, but they had to be fully paid for, since the US Neutrality Act made it impossible to lend credit to countries at war. It was hoped that these measures would allow Britain to protect itself without American intervention. But this proved to be such a drain on British finances that Roosevelt devised a scheme in 1941 whereby the US could lend, lease, sell, exchange, or otherwise dispose of military equipment to its allies. The US, in Roosevelt’s words, would be “the great arsenal of democracy.” But before the Lend-Lease Act was passed in March 1941, Britain had to dump assets in the US for much less than their real worth and hand over South African gold reserves as well. And the loan of war materials still had to be repaid by giving the US rights to British bases overseas. It was a hard bargain, which Churchill delicately but not quite accurately called “the most unsordid act in whole of recorded history.”21

Roosevelt defended his decision to help American allies in one of his most quoted speeches, the State of the Union address on January 6, 1941. He said the US could not stand aside in the war against dictators. Americans had to be prepared to defend themselves and help the free nations. But he also laid out his vision for the future, which was a mixture of old and new ideas. The mission should be to fight for four essential human freedoms: freedom of expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear of physical aggression. And these should be defended “everywhere in the world.” It was as though the New Deal had become a universal American goal. The speech ended: “This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God. Freedom means the supremacy of human rights everywhere. Our support goes to those who struggle to gain those rights and keep them. Our strength is our unity of purpose.”

The words that would haunt the Special Relationship, certainly while Churchill was alive, were “everywhere in the world.” And “the supremacy of human rights” was not traditionally why countries went to war. But the aim to save the world from barbarism and establish a liberal order was rooted in older notions of Manifest Destiny and the proselytizing spirit of Christianity, especially in its Protestant forms. When territorial conflicts between Britain and the US were resolved in the Treaty of Washington in 1871, an Anglo-American union was briefly proposed, which, in the words of a Washington newspaper, “would enable the English-speaking peoples to give law to the world, and at the same time be the means of increasing and strengthening the people everywhere who are struggling to secure for themselves, and for their children, the inestimable blessing which we now enjoy—the God-given right of self-government.”22 Roosevelt’s words were not quite so high flown, and Manifest Destiny was not foremost in his mind, but rhetorically, at least, the Anglo-American relationship was becoming more like the alliance Churchill had been hoping for all along.

Harry Hopkins, New Dealer and confidant to the president, was asked to administer Lend-Lease. In January 1941, Hopkins, a frail man never in the best of health, was sent to Britain to assess the situation. Refreshingly direct in his manner, Hopkins expressed a concern that Churchill disliked Americans, including their president. Churchill replied that this was an entirely false impression, no doubt spread maliciously by that Irish American ambassador, Joseph Kennedy.

After a lavish dinner by candlelight held in Hopkins’s honor at Ditchley Park, Churchill gave a rambling speech, designed perhaps to appeal to his guest’s New Deal sentiments. Churchill spoke of a new era of freedom and peace, where the humble English worker would feel safe and sound in his cottage home, equal before the law, and without fear of the knock on the door by the secret police. Those, he concluded, were the only British war aims. Hopkins rose to his feet, and drawled in his Iowa accent: “Well, Mr. Prime Minister, I don’t think the president will give a damn for your cottagers.” He paused, while the shocked company drew its breath: “You see, we’re only interested in seeing that goddamn son of a bitch Hitler get licked.” After that, Churchill saw that all was well, and the diners amused themselves by watching a newsreel of Hitler and Mussolini meeting at the Brenner Pass, which one of the guests declared to be “funnier than anything Charlie Chaplin produced in The Great Dictator.”23

But the Americans still had not committed themselves to entering the war. Letters went back and forth from Former Naval Person to President Roosevelt, keeping the president abreast of mostly disastrous military affairs in North Africa and the Middle East. Germany launched its war on the Soviet Union in June 1941, and Churchill told his assistant private secretary Jock Colville that it was essential to help the Russians. Still a staunch anti-Communist, Churchill said that if Hitler invaded hell, he would make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.

In late July, Churchill finally got his wish to meet Roosevelt. Harry Hopkins told him the president was now ready to see him. The second encounter between the two men obviously couldn’t be on neutral US territory, so it took place, quite appropriately, at sea, in Newfoundland.

Churchill’s own account of the war is not always reliable. He wrote, or at least supervised the writing of, his multivolume The Second World War, in the late 1940s and early 1950s. One topic about which he could not be candid was the patchy Anglo-American relationship. After completing the final volume in 1953, he reassured President Eisenhower that nothing he wrote would “impair the sympathy and understanding which exists between our two countries.” But there is no reason to doubt the veracity of Churchill’s description of his sea voyage to Newfoundland.

Churchill boarded the Prince of Wales on August 4, together with Harry Hopkins and some of Britain’s top military staff. A letter was sent by Former Naval Person to remind the president that it was “twenty-seven years ago to-day that Huns began their last war. We must make a good job of it this time. Twice ought to be enough. Look forward so much to our meeting.”24 This was assuming a little too much, perhaps, since 80 percent of Americans, according to opinion polls, still opposed any involvement of US troops in the war.

Churchill was full of hope, however, as he settled down in choppy seas to read C. S. Forester’s novel Captain Hornblower, R.N., about a Royal Navy captain swashbuckling his way through the Napoleonic Wars. He also watched That Hamilton Woman, a movie he had already seen four times (and misnamed Lady Hamilton nonetheless). Laurence Olivier plays Admiral Nelson to great effect. The Battle of Trafalgar is shown with much panache. A few months before, the New York Times critic had praised the movie in stirring terms: “Now that the spirit of Nelson is again at large upon the deep and the expectations of England are being triumphantly fulfilled, it is altogether fitting that the greatest Admiral ever to lead a British fleet, at this moment should be pictured with profound affection and respect upon the screen.”25

Churchill made a little speech after the screening: “Gentlemen, I thought the film would interest you, showing great events similar to those in which you have been taking part.”

Roosevelt, in the meantime, keen to avoid any impression that he wanted his country to take a direct part in those great events, pretended to go out on a recreational cruise on his presidential yacht. In the open seas he slipped on board the USS Augusta, with his most senior military officers, including General George Marshall. Unlike the camouflaged British battleships, the US Navy ships were painted in a pristine gray.

Nearing Newfoundland, Churchill, dressed in the uniform of Trinity House, a British outfit that administered lighthouses, turned to Hopkins a bit nervously and wondered whether Roosevelt would like him. Hopkins assured him that he would. “You’d have thought,” Hopkins recalled later, “Winston was being carried up into the heavens to meet God.”26 The true nature of how the Special Relationship would develop over time could not have been expressed more succinctly.

What followed was a great deal of fraternal pomp, visits, and return visits between the Prince of Wales and Augusta, mingling of the ships’ crews, bands playing national anthems, and discussions between British and American admirals and generals, which didn’t really go anywhere: the war-hardened British found the Americans a little wet behind the ears, and the Americans were still wary of British motives. Churchill eagerly awaited a statement from Roosevelt that the US would finally do battle as an Allied nation. But the president had something else in mind: a joint declaration of broad principles, somewhat along the lines of his State of the Union address, and the Four Freedoms.

This was not exactly what Churchill had hoped for. He writes a little defensively in his war memoirs, “Considering all the tales of my reactionary, Old World outlook, and the pain this is said to have caused the President, I am glad it should be on record that the substance and spirit of what came to be called the ‘Atlantic Charter’ was in its first draft a British production cast in my own words.”27

Perhaps. There was much in it the two leaders could agree upon: that neither country sought aggrandizement, territorial or otherwise; that no territorial changes would be made against the freely expressed wishes of the people concerned; that people should have the right to choose the form of government under which they would live; that essential produce would be distributed fairly, domestically and between nations; and that international organization would ensure peace in the world and allow people to traverse “the seas and oceans without fear of lawless assault or the need of maintaining burdensome armaments.”

There were, however, a few sticking points that revealed fissures in the Anglo-American fraternity (this was still a man’s world). The US insisted that there should be free trade in the world “without discrimination.” Despite Churchill’s own rousing defense of free trade during Joseph Chamberlain’s tariff campaign in 1903, he now felt constrained to protect the special trade agreements struck between the dominions and colonies of the British Empire (“imperial preference”). Churchill insisted on taking out the words “without discrimination” and inserting a clause about “existing obligations.” He got his way.