Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

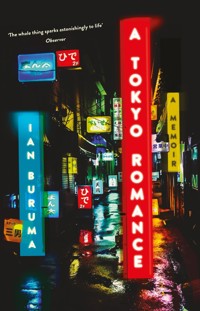

When Ian Buruma arrived in Tokyo as a young film student in 1975, he found a feverish and surreal metropolis in the midst of an economic boom, where everything seemed new and history only remained in fragments. Through his adventures in the world of avant-garde theatre, his encounters with carnival acts, fashion photographers and moments on-set with Akira Kurosawa, Buruma came of age. For an outsider, unattached to the cultural burdens placed on the Japanese, this was a place to be truly free. A Tokyo Romance is a portrait of a young artist and the fantastical city that shaped him, and a timeless story about the desire to transgress boundaries: cultural, artistic and sexual.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 314

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ATokyoRomance

ALSO BY IAN BURUMA

Their Promised Land: My Grandparents in Love and War

Theater of Cruelty: Art, Film, and the Shadows of War

Year Zero: A History of 1945

Taming the Gods: Religion and Democracy on Three Continents

The China Lover: A Novel

Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

Inventing Japan: 1853–1964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Playing the Game: A Novel

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons,Sacred Mothers, Transvestites, Gangsters, Driftersand Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo

(text by Donald Richie; photographs by Ian Buruma)

First published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Ian Buruma, 2018

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78239-799-1

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-800-4

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-801-1

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-802-8

Photographs by the author

Designed by Amanda Dewey

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In memory of Donald Richie, Norman Yonemoto, and Terayama Shuji

Cultural initiation entails metamorphosis, and we cannot learn any foreign values if we do not accept the risk of being transformed by what we learn.

— Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness,New York: NYRB, 2011

ATokyoRomance

ONE

The last thing he said to me, before I closed the door of his smartly decorated loft apartment in Amsterdam, was to stay away from Donald Richie’s crowd. This was in the summer of 1975. I can’t remember the name of the man who offered this advice, but I have a vague memory of what he looked like: close-cropped gray hair, hawkish nose, an elegant cotton or linen jacket; midsixties, I guessed, a designer perhaps, or a retired advertising executive. He had lived in Japan for some years, before retiring in Amsterdam.

Donald Richie introduced Japanese cinema to the West. I knew that much about him. That he was also a novelist, the author of a famous book about traveling around the Japanese Inland Sea, much praised by Christopher Isherwood, and the director of short films that had become classics of the 1960s Japanese avant-garde I didn’t know. But I had read two of his books on Japanese movies and was instantly drawn to the tone of his prose: witty, in a wry, detached way, and polished without being arch or prissy. Reading Richie made me want to meet him, always a perilous step for a fan that can easily end in sharp disillusion. There was not much biographical information on the covers of his books, but his 1971 introduction to Japanese Cinema was written in New York, so I assumed that he was an American.

In any case, I was still in Amsterdam, and Richie was, so far as I knew, in the United States, or possibly in Japan, where I was bound in a month or two, for the first time in my life. My Pakistan International Airlines ticket had been booked. My place at the film department of Nihon University College of Art in Tokyo was secure, as was the Japanese government scholarship that would pay for my living expenses. The thought of moving to Tokyo for several years was intensely exciting but alarming too. Would I be isolated and homesick and spend much of my time writing to people six thousand miles away? Would I come back in a few months, humiliated by moral defeat? I had a Japanese girlfriend named Sumie, who would move to Japan as well, but still.

One of the most appealing features of Richie’s books on Japanese cinema was the way he used the movies to describe so much else about Japanese life. You got a vivid idea of what people were like over there, how they behaved in love, or in anger, their bittersweet resignation in the face of the unavoidable, their sense of humor, their sensitivity to the transience of things, the tension between personal desires and public obligations, and so on.

Richie’s fond picture of Japan through its movies was not particularly exotic. But then exoticism had never been Japan’s main attraction to me anyway. Nor was I interested in traditional pursuits like Zen Buddhism, or tea ceremonies, let alone the rigors of the martial arts. The imaginary characters in the movies described by Richie seemed recognizably human, more human indeed than characters in most American or even European films I had seen. Or maybe it was the common humanity of figures in an unfamiliar setting that made it seem that way. Perhaps that is what excited me most about Japan, which was still no more than an idea, an image in my mind: the cultural strangeness mixed with that sense of raw humanity that I got from the movies, some of which I had seen in art houses in Amsterdam and London, or at the Paris Cinémathèque française, and some of which I had only read about in Donald Richie’s books.

I actually stumbled into Japan by accident. Asian culture had played no part in my childhood in Holland, even though The Hague, my hometown, still had a nostalgic whiff of “the Orient,” since people returning from the East Indian colonies used to retire there in large nineteenth-century mansions near the sea, complaining of the cold and damp climate, missing the easy life, the clubs, the tropical landscapes, and the servants. I liked Indonesian food, one of the few reminders of the recent colonial past, and the peculiar Indo-Dutch variety of Chinese cuisine: fat oversized spring rolls, thick and oily fried noodles with a fiery Indonesian sambal sauce made of chilies and garlic, the delicacy of the original coarsened by the greed of northern European appetites. My father’s elder sister had the misfortune of being sent out to the Dutch East Indies as a nanny just before World War II; she ended up spending most of her time in a particularly grim Japanese POW camp. So no nostalgia there.

Asia meant very little to me. But ever since I can remember I dreamed of leaving the safe and slightly dull surroundings of my upper-middle-class childhood, a world of garden sprinklers, club ties, bridge parties, and the sound of tennis balls in summer. As a child, I was fascinated by the story of Aladdin, rubbing his magic lamp. It is possible that the mix of enchanted travels and faraway lands (he lived in an unspecified city in China) left a mark. The Hague was in any case not where I intended to end up.

Perhaps I was prejudiced from an early age against my native country. My mother was British, born in London, the eldest daughter in a highly cultured Anglo-German-Jewish family, which in my provincial eyes seemed immensely sophisticated. My uncle, John Schlesinger, whom I adored, was a well-known film director. He was also openly gay, and his milieu of actors, artists, and musicians added further spice to the air of refinement I soaked up vicariously. Like many artists, John was both self-absorbed and open to new sensations, anything that stirred his imagination. He wanted to be amused, surprised, stimulated. And so I was always eager to impress, giving a performance of one kind or another, mimicking mannerisms, styles of dress, or opinions that I thought might spark his interest. Of course, despite the posturing, I never felt I was being interesting enough. And recalling my efforts in retrospect is more than a little embarrassing.

But in fact performance came naturally to me. I grew up with two cultures: lapsed Dutch Protestant on my father’s side, assimilated Anglo-Jewish on my mother’s. I could “pass” in both, but never felt naturally at ease in either. My destiny was to be half in, half out— of almost anything. Passing was my default state. In the meantime, there was never any doubt in my mind that glamour was always somewhere else, in London, especially in my uncle’s house, when I was still living in Holland, but preferably somewhere farther afield, where I didn’t have to choose.

By the time I was finally liberated from school and set out to live for a year in London, being “into Asia” had become a fashionable attitude: hippie trips to India in a Volkswagen bus, a superficial acquaintance with Ravi Shankar’s sitar music, the cloying smell of joss sticks in tea shops selling hash paraphernalia and Tibetan trinkets. I got to know some Indian hippies in England, who made the most of their mysterious Eastern provenance and were far more successful with impressionable European women than I could ever have hoped to be. One of them, an Assamese Christian from Bangalore, named Michael, was as much of a performer as I was, and he used his exotic allure to the fullest advantage.

The first Japanese I ever met weren’t even really Japanese. In 1971, instead of heading east in a Volkswagen bus before settling down to study at university, I traveled west, to California. I was nineteen. I stayed at the house of a friend of my uncle’s in Los Angeles, an alcoholic brain surgeon (his hands were steady during operations, I was told). He introduced me to an intense young man named Norman Yonemoto. Slim, tall, with large myopic eyes, which bulged alarmingly when he got excited, Norman bore some resemblance to Peter Lorre, the German actor, in his role as Mr. Moto, the Japanese detective. Like so many young men who drifted to LA, Norman had movie ambitions. For the time being he was making gay porno films. The money was OK. But Norman took gay porno seriously. He was an artist.

Norman was a third-generation Japanese American, raised in what is now Silicon Valley, where his parents cultivated flowers. There was no talk about Japan, however, when Norman acted as my guide in Los Angeles, zooming around the freeways in his silver Volkswagen Beetle, usually in the company of Nick, his Nordic-looking boyfriend. We cruised along Santa Monica Boulevard, where handsome young hustlers who hadn’t made it into the movies hung back casually against parked cars, scanning the road for a pickup. We went downtown at night, where Mexican girls were paid by the dance in dark halls with broken neon lights. Transvestites trawled for drunken truck drivers in menacing little bars stuck behind the once glamorous art deco movie houses. The alcoholic brain surgeon took us to a miniature Western town, a kind of erotic theme park, named Dude City, with saloons entered through swinging doors, where naked boys in cowboy boots danced on the bar tops. An olive-skinned young man in a white T-shirt kissed me on the lips. The surgeon chuckled and whispered that he was Taiwanese.

This was Norman’s world, and it seemed a very long way from Japan. I was in a state of fascinated culture shock: Southern California was more exotic to me than any place I had ever seen, or would yet see in later years, stranger in its way to European eyes than Calcutta, Shanghai, or Tokyo. Whatever vestiges of a disjointed Japanese upbringing Norman might still have had up in the flower gardens of Santa Clara County, they had long been shed in favor of his California dream of rough sex and making movies. He embraced LA in all its tawdry glamour.

Rough sex was not for me. The kiss from the Taiwanese was as far as it went at Dude City. My sexual life at that stage had consisted of some fumbling affairs with a number of girls, and a few boys. Most of what I knew I had learned from a more experienced girl from Stuttgart with long blond hair and a Walküre figure who had taken me in hand in London with immense tact and tenderness. But what I lacked in real experience, I made up for in knowingness. Hanging out in gay bars, cruising downtown LA, seeing things I had never seen before, brought me a little closer, I thought, to the sophistication that I associated with my uncle and his friends. It was also very far away from the garden sprinklers of The Hague, which was perhaps the main point.

Norman’s younger brother Bruce, who joined us one day from Berkeley, where he was studying art, was rather different. Like me, still searching for his sexual orientation, Bruce was more political than his brother, quicker to pick an argument; he was “into” French theorists. Paris, albeit just in the mind, was his intellectual center, more than LA. Unlike Norman, Bruce was also interested in Japan. This emerged one night when the three of us did a rather conventional thing for the time: we went to Disneyland, in the heart of Orange County, after sharing a tab of LSD.

My memories of that night are still vivid, even though jumbled up in a bit of a blur: The Supremes performed on a gilded stage, changing glittering costumes after every song— that, at any rate, is how I remember it. Norman’s eyes shone as he discoursed on the Southern Californian scene while pointing at the childlike caricatures of other cultures displayed in a ride named It’s a Small World. In my jacked-up mental state I kept wondering what it all meant, which led to feverish discussions about the meaning of “it.”

Compared with Norman’s wide-eyed animation, Bruce’s soft round face, a little like a painting of a Japanese Buddha, betrayed little. But something in our acid-fueled experience of this Californian fantasy world sparked an argument about identity, less about the meaning of “it” than about who we were and where we came from. “We are Americans,” cried Norman in a state of great agitation. “We get to make ourselves over. We can be whatever we want.” Whereupon Bruce said: “What about thousands of years of Japanese culture? All that can’t just disappear. Anyway, when whites look at us, they don’t see Americans, they see Asians. We’re Asians, whether we like it or not.”

There was nothing much I could contribute to this discussion. And perhaps not too much should be made of these earnest attempts at self-definition. But I like to think that on that night, somewhere between the Pirates of the Caribbean and the Jungle Cruise, a seed of my future orientation toward Japan was planted. For it was not long after that, back in Holland, that I had to make up my mind what to study at university. I tried the law for a month or two before deciding it was not for me. I had already dabbled in art history, at the Courtauld Institute in London, where I worked in the picture library and attended lectures on Picasso by the art historian and former Soviet spy Anthony Blunt. One day, while I was studying a picture of a Joan Miró painting, I felt the stale breath of a man leaning over my shoulder, who exclaimed: “Is that art?” A burly figure in a tweed jacket, he was an expert in medieval English church foundations. I concluded that art history wasn’t really for me either.

And so I plumped for Chinese. It was different, it sounded glamorous, it might be useful one day, I liked Chinese food, and possibly lodged somewhere in the back of my mind were memories of Aladdin, Disneyland, or that Taiwanese boy in Dude City.

This was in 1971. China was still in the last throes of the Cultural Revolution. Few people bothered to learn Chinese at Leyden University then. Fewer still could have any hope of ever visiting China, which was accessible only to group tours organized by friends of the Chinese people. These were not my friends. The department of Sinology, housed in a former lunatic asylum, was tiny. My fellow students could be neatly divided into two groups: dreamers enamored by the distant romance of Maoism, and scholars who wanted to spend the rest of their lives grazing such academic fields as Tang poetry or Han dynasty law. I did not fit into either category, and was never a happy Sinologist. I spent more time in that first year dancing with Chinese boys at the DOK disco club in Amsterdam than I did on classical Chinese. The sensual allure of “the East,” first glimpsed in those Indian friends in London, was more tangible on the DOK dance floor than in the Analects of Confucius.

China seemed impossibly remote, an abstraction really, like a distant planet. And the modern texts we had to read, culled from Communist Party publications like Red Flag, or the People’s Daily, were so deadened by the wooden jargon of official rhetoric, such a sad degradation of the concise beauty of classical Chinese, that my interest in contemporary China soon ran dry. One of the worst insults to the traditional economy of the written Chinese language was the way sentences would run on and on, as though they were literal translations from Karl Marx’s German. And the heavy-handed sarcasm owed more to the official Soviet style than to anything in the Chinese rhetorical tradition.

Then two things happened to steer me in a different direction. I saw a movie by François Truffaut, entitled Bed and Board (Domicile Conjugal). The story was relatively simple. A nice young man in Paris, named Antoine, played by Truffaut’s favorite actor and alter ego Jean-Pierre Léaud, has just got married to Christine, a nice French girl (Claude Jade). She is already pregnant with their first child. One day, on a job for an American firm, Antoine meets Kyoko, the daughter of a Japanese business client: willowy, with long shiny black hair and dark eyes set in a pale moon face, and dressed in an exquisite kimono, Kyoko, acted by the famous Pierre Cardin model Hiroko, shimmers on the screen like a mysterious Oriental fantasy.

And that is exactly what she turns out to be: a mirage. Antoine is hopelessly smitten by her silky beauty and her strange and graceful manners: little paper flowers that open in glasses of water to reveal her amorous sentiments for Antoine, and similarly exotic refinements. Christine, who has had her baby by now, realizes that Antoine is cheating on her. For a while Antoine can’t help himself, but in the end the dream begins to pall. He and Kyoko have nothing to say to each other. Paper flowers and sweet accented nothings are no longer enough. He longs for the familiar bourgeois certainties of Christine. The Oriental hallucination fades. Antoine comes down to earth. Husband, wife, and baby son get back together on solid French terrain.

It is a charming film, not Truffaut’s very best perhaps, but wise and funny. I suppose the idea was to warn the viewer not to be taken in by exotic fantasies; true depth of feeling can only be found with people who have a culture in common. Transcending the borders of language and shared assumptions will result in disillusion.

I’m afraid that I refused to get the message. I fell in love with Kyoko. I wanted a Kyoko in my life, perhaps even more than one. How happy I would be in the land of Kyokos.

More than twenty years later, when I was living in London, I received an invitation to be part of a jury at a modest film festival in France. And there, among my fellow jury members, was a stylish middle-aged Japanese lady dressed in a kimono with a discreet pattern of pink cherry blossoms on a pale blue background. Hiroko, the former Pierre Cardin model and star in Truffaut’s film, was now the wife of a grand French fashion executive. I told her how I had once fallen in love with her. She replied in her soft tinkling voice: “Ça m’arrive souvent”; you’re not the first one to say that.

It must have been around the time I first set eyes on Kyoko, in 1972 or 1973, that I first saw a performance of Terayama Shuji’s theater group, Tenjo Sajiki, at the Mickery Theater in Amsterdam. Mickery, located in a former cinema, whose art deco fixtures were left intact, was for some years a mecca of avant-garde theater from all over the world. The young Willem Dafoe performed there with Theatre X and later the Wooster Group. There were groups from Poland, Nigeria, as well as most of the artistic capitals of the West. One of the more memorable visits was by a drama workshop formed by convicts at San Quentin prison in California (young women queued up around the block to meet the ex-cons). I used to go to Mickery regularly, hanging out, as was customary at the time, with the actors in the café after their performances.

Tenjo Sajiki, meaning the cheapest seats in the theater, or “the Gods” in English, was from Tokyo. The founder and director, Terayama Shuji, an aloof but charismatic figure dressed in dark suits and blue high-heeled denim shoes, was a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, photographer, and filmmaker, who functioned as a kind of Pied Piper in Tokyo, gathering around him a shifting retinue of runaways, misfits, and eccentrics, who acted as living props in his surreal theatrical fantasies. Terayama’s plays and movies owed something to various Western influences— a bit of Fellini here, Robert Wilson there— but far more to Japanese fairground entertainments, carnival freaks, striptease shows, and other forms of theatrical lowlife.

Seeing the Tenjo Sajiki for the first time was like squinting through the keyhole of a grotesque peep show full of extraordinary goings-on. I had never seen anything remotely like it. It brought back old memories of magic boxes, lit from the inside, full of strange objects I had concocted with a child’s morbid imagination.

The first play I witnessed at the Mickery in 1972 was entitled Ahen Senso, or Opium War. Less a coherent story than a series of tableaux, Opium War was staged outside the theater, as well as inside, where the public was led by a succession of guides into different rooms, decorated with old Japanese movie posters, blown-up details of erotic woodblock prints, lurid comic books, and props that seemed to have been lifted from a 1920s whorehouse. Naked girls were displayed in a variety of peculiar poses, and ventriloquists in chalky Kabuki makeup spoke through dolls dressed like Toulouse-Lautrec while being whipped by a female dominatrix in a black SS cap reciting a Japanese poem. Kimonoed ogres from ancient Japanese ghost stories mingled with men in women’s makeup wearing World War II uniforms. One naked man had Chinese characters tattooed all over his body. A beautiful young girl in a purple Chinese dress cut the head off a live chicken. The air of violence and the fact that at certain times we were boxed into metal cages caused an older man in the audience to panic; it reminded him of his incarceration in a Japanese POW camp as a child. During a performance in Germany, members of the audience had accidentally been set on fire. There were rumors of fistfights between actors and the public, which fitted Terayama’s vision of theater as a kind of criminal enterprise. All this was accompanied by music, sometimes soft and seductive, sometimes deafening and faintly sinister, a mixture of Pink Floyd– like psychedelic riffs, prewar Japanese popular tunes, and Buddhist chanting, composed and performed by a long-haired man named J. A. Caesar in a top hat. It was deeply weird, over-the-top, largely unintelligible, perversely erotic, rather frightening, and totally unforgettable.

After the performance the petite young actors gathered in the café. But since only a few of them spoke broken English, the barrier between performers and public was barely breached. They were dressed like hip young Westerners— jeans, leather jackets, boots, velvet pants. But some also wore wooden Japanese geta and padded kimono jackets. The Tenjo Sajiki seemed to be from a world that was at once familiar, or at least recognizable, and utterly strange. I knew that I had witnessed a theatrical fantasy, but I still thought that if Tokyo was anything like this, I needed to join the circus and get out of town. Going back to the leaden prose of Red Flag or the Confucian classics was a letdown after Terayama Shuji and his troupe. To Tokyo, I thought. As soon as possible.

I can’t remember what other advice I was given by the man in Amsterdam, apart from staying away from Donald Richie’s crowd. Nor did he divulge why Richie’s company was so reprehensible. Despite my air of knowingness, I was still a callow youth (“You don’t know much about people, do you?” said a Franco-Vietnamese fashion designer, after he picked me up at the DOK disco, where he had bragged about an affair with Alain Delon). But I knew enough to suspect some homosexual rivalry, some fit of social pique. I didn’t care: to Tokyo!

The Tenjo Sajiki

TWO

What astonished me about Tokyo on first sight in the fall of 1975 was how much it resembled a Tenjo Sajiki theater set. I assumed that Terayama’s spectacles were the madly exaggerated, surreal fantasies of a poet’s feverish mind. To be sure, I did not come across ventriloquists in nineteenth-century French clothes being whipped by leather-clad dominatrices. But there was something theatrical, even hallucinatory, about the cityscape itself, where nothing was understated; representations of products, places, entertainment, restaurants, fashion, and so on were everywhere screaming for attention.

Chinese characters, which I had studied so painstakingly at Leyden University, loomed high in plastic or neon over freeways or outside the main railway stations, on banners hanging down from tall office buildings, on painted signs outside movie theaters and nightclubs known as “cabarets,” promising all manner of diversions that would have been hidden from sight in most Western cities. In Tokyo, it seemed, very little was out of sight.

Donald Richie, I later learned, did not read Chinese or Japanese script, luckily for him, as his friend the eminent scholar of Japanese literature Edward Seidensticker once remarked a little tartly: the gracefully painted or luridly neon-lit characters, many of them of very ancient origin, looked beautifully exotic, as long as you didn’t know what they signified—commercials for soft drinks, say, or clinics specializing in the treatment of piles (surprisingly common in Japan).

The visual density of Tokyo was overwhelming. In the first few weeks I just walked around in a daze, a lone foreigner bobbing along in crowds of neatly dressed dark-haired people, taking everything in with my eyes, before I learned how to speak properly or read. I just walked and walked, often losing my way in the maze of streets in Shinjuku or Shibuya. Much of the advertising was in the same intense hues as the azure skies of early autumn. I realized now that the colors in old Japanese woodcuts were not stylized at all, but an accurate depiction of Japanese light. Plastic chrysanthemums in burnt orange and gold were strung along the narrow shopping streets to mark the season. The visual barrage of neon lights, crimson lanterns, and movie posters was matched by the cacophony of mechanical noise: from Japanese pop tunes, advertising jingles, record stores, cabarets, theaters, and PA systems in train stations, and blaring forth from TV sets left on all day and night in coffee shops, bars, and restaurants. It made J. A. Caesar’s background music to the Tenjo Sajiki plays seem almost hushed.

I did not delve into the thick of Japanese life immediately. For several weeks, before looking for an apartment with my girlfriend, Sumie, I stayed in a kind of buffer zone, a cultural halfway house. A British relative, named Ashley Raeburn, was the representative of Shell in Japan. He lived with his wife, Nest, in a huge mansion in Aobadai, a plush hilly district high above the tumult of the main commercial hubs of the city. Behind the house was a wide sloping lawn, kept green in all seasons, where we played croquet on Sundays. The sound of sprinklers reminded me of my childhood in The Hague. Ashley was driven to his work in a Rolls-Royce. Food was served at a long chestnut table, polished to a high sheen, by one of the uniformed staff, summoned after each course with a bell. The contrast with the city I took in with my eyes and ears during the day could not have been greater. As long as I stayed with Ashley and Nest, Tokyo was still a spectacle, a kind of theater, from which I could retreat every evening into the quasi-colonial opulence of Aobadai.

The only glimpses I got of a strictly Japanese world in Ashley’s mansion were entirely belowstairs, as they used to call it in grand English country houses. Sitting by the fire with Ashley and Nest, cradling an after-dinner whiskey while discussing Japan and the Japanese, was comfortable enough. But I preferred having endless cups of green tea in the kitchen, trying hard to straighten out my broken Japanese with the chauffeur, a jokey ex-policeman, or the cook, and the kind ladies who served us at dinner. Being given rides in the Shell Rolls-Royce made me feel conspicuous and was something of an embarrassment. But my preference for belowstairs was less a matter of reverse snobbery than a desire to penetrate the mysteries of Japan. If I was to fit in, I had better learn fast. It was in the kitchen that I received my first lessons in linguistic etiquette, how to use different forms depending on who I was talking to. The chauffeur and the cook could address me in familiar language, since I was much younger than they were. But I had to address them in more deferential terms. Not just idioms, but personal pronouns and even verb endings change according to age, gender, and social status. This essential part of the Japanese language is not only hard to master at first, but becomes increasingly important as one’s skill improves. One difficulty I faced was that I spoke feminine Japanese by mimicking my girlfriend, which made me sound a bit like a simpering drag queen. And I would soon learn that the more fluent one became in Japanese, the more jarring slips in etiquette would sound to the native ear. Since my Japanese was still quite basic, my infelicities at Aobadai were forgiven.

Roaming around Tokyo by day, I thought of my culture shock when I first saw Los Angeles, that sense of being on a huge movie set, quickly built and quick to come down, with its architectural fantasies of Tudor, Mexican Moorish, Scottish Baronial, and French beaux arts. It was a shock because I had never seen such a city before. Accustomed to the solidity of historic cities in Europe, I was both fascinated by LA and a trifle smug, as though growing up in a more antique environment conveyed some kind of moral superiority. Tokyo, like many postwar Asian cities, with their ubiquitous billboards and strip malls, owed a lot to the Southern Californian model, but Tokyo’s density— the crowds, the noise, the visual excess— made LA seem staid in comparison.

One particular coffee shop sticks in my mind as a typical example of the city I first saw in the mid-1970s. It was called Versailles, located underground, near the east exit of Shinjuku station, one of the largest stations in Tokyo. To get there you had to go down some steep concrete steps, with the noise of advertising jingles from a famous camera store still ringing in your ears. All of a sudden, there you were, in the drawing room of an eighteenth-century French château, with candelabras, marble walls, gilded Louis XIV– ish furniture, and the sound of baroque music. Naturally, everything was made of plastic and plywood. People spent hours in this ersatz splendor, smoking and reading comic books, while listening to Richard Clayderman tinkling Eine kleine Nachtmusik. Versailles was demolished a long time ago, as were most coffee shops of that time. There might be a Starbucks there now, or a restaurant offering a fusion of Japanese and northern Italian cuisine.

Much of what I first observed in 1975 had been built in the 1960s, when the economic boom was gathering speed. Nothing much older was to be seen, apart from some temples and shrines, and a few early twentieth century brick buildings that survived firestorms and bombs. Tokyo had been modernized along Western lines in the late nineteenth century, half destroyed by an earthquake in 1923, and reduced to miles of rubble by American bombs in 1945. The sixties were a great period for cheap fantasy architecture. After years of austerity following the ruinous war, there was a hunger for real, but mostly still imaginary, luxury. Few Japanese in those days had the means to travel abroad, and so a make-believe abroad was built in Japan to cater to people’s dreams, hence the Louis XIV cafés, or the German beer halls, or a well-known short-time hotel, named the Queen Elizabeth 2, built of concrete in the shape of an ocean liner, complete with recorded foghorns.

The first Disneyland to be built outside the United States was in Japan, in 1983, not far from Narita International Airport. Donald Richie once wrote that there was no need for one, for the Japanese already had a Disneyland called Tokyo. The nonresidential areas of the city certainly had the ephemeral air of a theme park. Richie’s admirer, Christopher Isherwood, the British novelist who had made Los Angeles his home after living in Berlin before the war, wrote the following words about his adopted city: “What was there, on this shore, a hundred years ago? And which, of all these flimsy structures, will be standing a hundred years from now? Probably not a single one. Well, I like that thought. It is bracingly realistic. In such surroundings, it is easier to remember and accept the fact that you won’t be here, either.”*

There is something very Japanese in this sentiment, the quiet acceptance of evanescence. I quoted Isherwood’s words at the memorial for Norman Yonemoto, who died in Los Angeles in 2014.

I think Isherwood would have liked Tokyo in the 1970s. The wartime gloom had made way for frenetic hedonism. But above all, the sense of illusion would have appealed to his penchant for Oriental mysticism, the idea of the fleetingness of things. There is nevertheless an important difference between Tokyo and LA. History does not run deep in LA, whereas Tokyo, or Edo as it used to be called, was already a small castle town in the twelfth century. In the eighteenth century, Edo was the second-largest city in the world, after Beijing. So the plastic-fantastic Tokyo I encountered in 1975, with its motley collection of pastiche buildings, owing something to many parts of the world, albeit in a much altered form, was built on deep layers of history.

The palimpsest that is modern Tokyo still shows traces of its past, in the layout of the streets, for example. But history mostly lives on in historical memory expressed in popular culture, as myth. Even the very recent past was steeped in legend in Tokyo. Just a few years into the new decade, the sixties were already remembered in a haze of nostalgia for youthful rebellion and experiment. “You should have been here then,” the old hands would say. Ah, the student demos in 1968, the underground the-ater performances at Hanazono Shrine, the “happenings” near Shinjuku station, where the local hippies known as futenzoku (crazy tribe) hung out, the early movies of Oshima Nagisa, the posters by Yokoo Tadanori, Shinoyama Kishin’s photography, the foundation of Butoh dance by Hijikata Tatsumi.

By the time I arrived, the futenzoku had moved on. You were more likely to encounter the last mutilated World War II veterans in white kimonos and wooden limbs playing sad wartime ballads on accordions at Shinjuku station than hippies strumming guitars. Some would say that the party came to a neatly timed end in 1970 with the suicide of Mishima Yukio, the novelist who staged his violent samurai death by slitting his stomach surrounded by his uniformed band of handsome young militiamen after a failed coup d’état at a military base in the middle of Tokyo. In fact, cultures don’t end so much as mutate. By 1975, the rebels of the previous decades, including Terayama Shuji, had become respected figures, were given prestigious prizes, and were invited to international festivals.

Perhaps it is the speed of destruction and construction in Tokyo that evokes nostalgia. There was always a “then” that was sorely missed. Not so very long ago the entire city was made up of canals and wooden houses, which regularly went up in flames in firestorms called the “Flowers of Edo.” Very few buildings were meant to last forever: no great stone cathedrals. The monumental is not part of the Japanese style. History in Tokyo is only visible in fragments: a ruined nobleman’s garden here, a rebuilt Shinto shrine there, or a tiny bar, now sadly forsaken, where Mishima once held court.

Donald Richie was a young reporter for the Stars and Stripes