11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

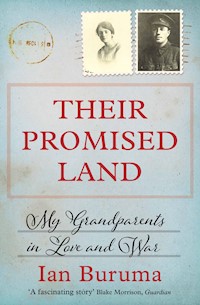

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Ian Buruma's maternal grandparents, Bernard and Winifred (Bun & Win), wrote to each other regularly throughout their life together. The first letters were written in 1915, when Bun was still at school at Uppingham and Win was taking music lessons in Hampstead. They were married for more than sixty years, but the heart of their remarkable story lies within the span of the two world wars. After a brief separation, when Bernard served as a stretcher bearer on the Western Front during the Great War, the couple exchanged letters whenever they were apart. Most of them were written during the Second World War and their correspondence is filled with vivid accounts of wartime activity at home and abroad. Bernard was stationed in India as an army doctor, while Win struggled through wartime privation and the Blitz to hold her family together, including their eldest son, the later film director John Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy, Sunday Bloody Sunday), and twelve Jewish children they had arranged to be rescued from Nazi Germany. Their letters are a priceless record of an assimilated Jewish family living in England throughout the upheavals of the twentieth century and a moving portrait of a loving couple separated by war. By using their own words, Ian Buruma has created a spellbinding homage to the sustaining power of a family's love and devotion through very dark days

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

ALSO BY I AN BURUMA

Theater of Cruelty: Art, Film, and the Shadows of War

Year Zero: A History of 1945

Taming the Gods: Religion and Democracy on Three Continents

The China Lover: A Novel

Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

Inventing Japan: 1853-1964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

Playing the Game

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers, Transvestites, Gangsters, Drifters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo (text by Donald Richie, photographs by Ian Buruma)

First published in the United States of America in 2016 by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2016 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Ian Buruma, 2016

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84887-938-6 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-940-9 E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-541-6 Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-941-6

Printed in Great Britain Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26-27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Isabel and Josephine

CONTENTS

DON'T LIKE THE NAME

One

FIRST LOVE

Two

GOING TO WAR

Three

THE LONG WAIT

Four

SAFE HAVEN

Five

THE BEGINNING

Six

THE END OF THE BEGINNING

Seven

EMPIRE

Eight

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

Nine

THE END

Epitaph

Acknowledgements

Index

DON'T LIKE THE NAME

Asked whether he believed in happy marriage, Philip Roth replied: “Yes, and some people play the violin like Isaac Stern. But it’s rare.”

—Claudia Roth Pierpont, Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books

When I think of my maternal grandparents, I think of Christmas. Since they both lived into the 1980s, I can think of many other things too. But Christmas at St. Mary Woodlands House, the large vicarage in Berkshire where they lived next to Woodlands St. Mary’s, a mid-Victorian Gothic church, now no longer in use, will always be my childhood idyll.

Age in these memories is rather indistinct. Anything between six and fourteen, I suppose. Roughly between 1958 and 1966. Between grey Marks and Spencer shorts and my powder-blue Beatles hat.

Nothing could ever match the thrill of arriving late at night, exhausted and a little sick from spending much of the day in our family car thick with my mother’s cigarette smoke, having started early that morning in The Hague, crossing the choppy North Sea on a Belgian ferryboat smelling of petrol fumes and vomit (the British Rhine Army going home), waiting for hours in the customs shed at Dover, crawling endlessly along one-lane country roads, taking in the familiar English winter odours of soot and bonfire smoke, and then finally pulling into the gravelled drive of St. Mary Woodlands, to be greeted with the jovial laughter of my grandfather, “Grandpop,” wearing a green tweed jacket and smoking a pipe.

The two-storey house with its large windows and elephant-grey stucco walls was not grand, even though my memory has greatly expanded its size as though it were one of the great English country houses. It was not. But it was spacious. And it gave off a sense of solid Victorian comfort. A lawn, about the size of two football fields, at the rear of the house, flanked by broad flowerbeds tended by my grandmother, backed into a line of high oak trees, home to hundreds of cawing rooks, looking out to what is now the M4 motorway.

The lawn was used in summer for games of croquet and village fêtes. Ladies in hats inspected the wooden tables laden with prize fruits, vegetables, and homemade cakes. There were coconut shies, a tombola, and lucky dips. The vicar of St. Mary’s mingled with surgeons, retired colonels, assorted family members, and the odd local aristocrat, such as Lady S., who was cheerfully drunk before lunch, and usually accompanied by a formidable lady in tweeds, known to us as “Major C.” Sherry was served on the terrace. High tea came with cakes, scones, chocolate biscuits, and cucumber sandwiches. These domestic scenes were always bathed in sunshine, of course, followed by the long shadows and golden light of early summer evenings.

Christmas at St. Mary Woodlands, my sister and me

Just so, in my mind’s eye, the lawn never failed to be buried under a thick blanket of snow at Christmas.

After piling out of my father’s car, we would enter the house through the kitchen, where Laura, the beloved family cook, hovered over the stove, a cigarette dangling from the corner of her mouth on the verge of dripping ash onto a freshly roasted lamb.

There were other “char ladies” who loom large in my childhood memories, such as the toothless Mrs. Tuttle, the pale and birdlike Mrs. Dobson, and an enormously stout lady with a neighing laugh, named Mrs. Mackerell, with whose husband, “Old Butt,” my grandfather would repair once a year to a local pub for his Christmas drink.

To the side of the kitchen was Laura’s room, a dark, messy space with a strong whiff of sweat, dog, and unwashed stockings. This was where the only television set in the house was installed. TV was not really approved of by my grandparents, hence perhaps its banishment to the house’s least salubrious corner. I spent many happy hours there, alone or sometimes with Laura, watching English comedy shows in black and white (Frankie Howerd and Sidney James) and American westerns (The Lone Ranger and Gunsmoke). No one else watched television much. An exception was made when a member of the family was on the TV. My aunt Susan played Samuel Pepys’s wife in a series based on his diaries; my uncle John, before becoming a famous film director, made documentaries for the BBC about fine English cheeses, World War II generals, art school students, and Georges Simenon speaking about his sexual conquests through a haze of tobacco smoke. John also had a brief career as an actor. I remember seeing him in Laura’s room as a minstrel pretending to play the mandolin while singing a song to Roger Moore in an episode of Ivanhoe.

A narrow passage led from the kitchen to the main hall, where a wide and elegant staircase climbed to the bedrooms on the first floor. From early December onward the walls along the stairs were covered up to the ceiling in Christmas cards, hundreds and hundreds of them, like leaves of ivy on a garden wall. Making sure to send Christmas cards to everyone she knew, or who might possibly be offended if they didn’t get one, was an annual source of neurotic obsession for my grandmother, or “Granny,” who would be mortified to receive a card from anyone she might possibly have overlooked.

My grandmother and me in 1953

It was not just the Christmas cards that spoke of a certain air of excess. Everything about Christmas seemed a trifle overdone, certainly more lavish than anything we were used to at home in Holland—the mistletoe, the ubiquitous holly, the candles, and especially, in the large drawing room looking out onto the garden, the Christmas tree, whose opulence, like so much else, might be slightly magnified by memory, but not much. Dripping with gold and silver baubles, festooned with streams of glittery trimmings, angels dangling from pretty little candlesticks, the tree was topped by a shining angel stretching her arms all the way to the high ceiling. This totem of pagan abundance, looking over a small mountain range of beautifully wrapped presents at its base, was not really vulgar—Granny had excellent taste. It was just very, very big.

The impression was clear: here was a family that was serious about Christmas.

Christmas Day, for my two sisters and me, began as early as four or five o’clock in the morning, when we could no longer contain ourselves and would fall upon the Christmas stockings, seemingly made for giants, bulging with nuts, chocolates, fruits, and a panoply of presents. Gifts that were too bulky to be stuffed into these huge cotton sausages were tied to them with string: an illustrated edition of Kipling’s Jungle Book, a much-wished-for toy Colt revolver, a set of paints and brushes, a plastic model of a Lancaster bomber, and much more that I have forgotten. Family friends who stayed as guests and received equally bountiful stockings assumed that this was the extent of the Christmas presents, slightly baffled why this seasonal ritual was dealt with so early in the day. Little did they know.

After a cup of tea and biscuits taken in bed, a cooked breakfast was waiting for us on warm silver domed platters laid out on the mahogany sideboard in the downstairs dining room. There were sausages and tomatoes, devilled kidneys, plump brown kippers glistening in butter, scrambled, poached, or boiled eggs freshly hatched in the chicken coop next to the gardener’s cottage, and various kinds of toast with an assortment of homemade jams. This was just the beginning of a daylong feast of Edwardian gluttony, interrupted only by a brisk walk in the morning on the snowy top of Inkpen Beacon, marked by an old wooden gibbet where murderers used to be hanged. Then came the opening of presents after lunch, and a languid hour or two after tea of listening to classical music records presented to one another by the adults.

There was always music at St. Mary Woodlands. Classical music was a kind of family cult, and deep knowledge about opera, especially Wagner’s operas, as well as the music of Brahms, Mozart, and Beethoven, was almost a requirement. As was playing an instrument with some degree of skill. Granny had been a very fine violinist. Aunt Hilary had played the violin as a professional. And my mother, Wendy, was a keen amateur cellist. Uncle John had played the piano, but switched as a teenager, much to the dismay of his parents, to performing conjuring tricks. Hilary’s twin brother, Uncle Roger, once played the French horn. He probably knew more about music than anyone else—the classics, that is, modern music being dismissed as “plonkety-plonk,” and pop music as rubbish.

My father’s taste ran to jazz, which was tolerated in moderation, since he had after all married my mother, who shared some of his passions, but this was sometimes the subject of good-natured mockery. Noël Coward, revered by my grandfather— aside from Brahms, whose music never failed to bring a tear to his eyes—was one thing, Duke Ellington quite another. My own fondness as a teenager for Cliff Richard was, however, disapproved of. I could have my wished-for Cliff Richard records, but had to listen to The Young Ones or Expresso Bongo with the sound turned right down, my ears glued to the mono loudspeaker under the grand piano when no one else was around. Uncle John, who bought me my first Cliff Richard LPs, also included a record of Nat King Cole, whose songs were considered more elevating. I outgrew Cliff Richard but never really developed a taste for Nat King Cole.

Christmas lunch was a succession of traditional dishes, beautifully cooked by Laura: turkey filled with stuffing, sausages, bread sauce, and so on, followed by a rich plum pudding carried into the darkened dining room with much pomp by Laura, whose annual tear would drop into the flaming brandy.

In the old days, before World War II, when the family lived in London, my grandparents would dress up every night for dinner, while their children were confined to the nursery. Standards had been relaxed since then. And the family was no longer required to jump to attention during the monarch’s Christmas speech either.

Grandpop sat at the head of the table, an absurd paper hat from a Christmas cracker wrapped around his bald head and a pipe firmly lodged between his nicotine-stained teeth. He had the appearance of a friendly frog, his round face creased with laughter. He was a paediatrician, and his main prescription for a healthy life was the combination of fresh air and alcohol. When we were very small, he would offer us a brandy cork to sniff. When I was about fourteen I was given the choice between beer and cider to drink at lunch. My choice of cider did not entirely please him, since beer was considered a more manly drink. When the Christmas weather was especially severe, he would smack his lips and announce that he would spend the night outside on the lawn. Always on cue, my grandmother would protest (which was the whole point), and after a ritual palaver the plan was quietly abandoned.

My mother’s youngest sibling was Aunt Susan, the most bohemian among the immediate family members; she once insisted on travelling across Spain barefoot, leaving her with a painful skin disease. Susan was having some success as an actress, not just on television, but as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company (she played Nerissa in a famous Stratford production with Peter O’Toole as Shylock). We adored her. Other members of the family sitting around the Christmas table included Gabriel, Uncle Roger’s first wife, and their son, Paul. The men in my mother’s family were all short, stocky, and prematurely bald, and the women were even shorter and had thick wavy dark brown hair, except for Aunt Susan, who was fair, and Granny, whose perfectly coiffed hair was set in waves of salt and pepper.

Uncle John often invited a “chum” down for Christmas, who would share his bedroom. When I was very young, I never quite understood why these nice young men didn’t want to marry my aunt Susan. After all, they usually shared an interest in “the stage.”

The family conversation might best be described as a kind of creative chaos. The main thing was to be heard in the cacophony of stories and inside jokes. You had to be quick if you were to be noticed. Sharp wit and the skill to tell a good story were essential, preferably at the top of your voice. The worst possible sin was to be a bore. Faces under the coloured paper hats grew steadily ruddier as candles flickered in the silver candelabra and the contents of the Christmas crackers sprawled across the table amid the walnuts, the dried fruits, and the crystal glasses. Opera performances around Europe were recalled. Family anecdotes retold. John and Roger giggled like schoolboys. And Granny and Grandpop sat back and surveyed the scene with patriarchal and matriarchal pride.

No wonder these occasions could strike an outsider as a trifle overpowering. It was hard to get a word in. We were a tight-knit clan. And yet the family was far from closed to outsiders. On the contrary, my grandparents had a quasi-Oriental concept of hospitality. They took pride in the number of guests they welcomed at St. Mary Woodlands. It was a sign of their generosity. Rather like those Christmas cards in the hall, friends were proof of the family’s worth, even perhaps of its acceptance.

I cannot say I felt overpowered. But coming as my sisters and I were from a relatively provincial Dutch town, the glamour of family Christmas in England made our lives seem rather drab in comparison. If acceptance was an issue, it was about my place in the family, and the culture it represented. This was not a straightforward matter. Even the tightest-knit clans consist of concentric circles. At the centre, holding it all together, were the grandparents, Granny and Grandpop, Bernard and Winifred (“Bun” and “Win”), around whom everything revolved. The following circles were made up of the next generations. But the family extended further, to circles of great-uncles and -aunts, cousins, and nephews and nieces, and then there were even more distant relatives, some of them refugees from twentieth-century catastrophes, and an adopted family of twelve Jewish children whom my grandparents had helped to escape from Hitler’s Berlin.

I grew up in the warm embrace of the inner circle, trying to come up to the image I had of my grandparents, their grandeur in my eyes, St. Mary Woodlands.

An idyll is usually associated with a pastoral scene, a childhood Garden of Eden, a place to which there can be no return. Mine was set in a very English countryside. Everything about St. Mary Woodlands—the fêtes, the pony rides in summertime, the village cricket, and, above all, Christmas—seemed very, very English. And indeed, the superiority of Englishness, to my grandparents, was never in doubt. They were far too well travelled and cosmopolitan to look down on foreigners, let alone to exclude them. They were not like the guest at a local Sunday-morning drinks party, who replied to my mother’s casual remark, made in a flagging attempt at small talk, that our car in the drive was the only one with foreign number plates, that this was “nothing to be proud of.” On the contrary, English superiority would more often be expressed by being especially polite to foreigners, while being careful not to seem patronizing.

And yet my sisters and I were made aware from a very early age that there was something faintly amusing about our foreign background, about the way we spoke an incomprehensible guttural language, or “Double Dutch,” as the family would call it. John and his chums delighted in doing imitations of Queen Juliana’s admittedly comical accent in her efforts to speak English.

And so, to live up to the idyll of St. Mary Woodlands, I became something far more laughable than being foreign; I became a little Anglophile, an aspiration my grandparents, perhaps feeling secretly flattered, were happy to indulge: cricket bats and checked Viyella shirts for Christmas, regimental ties and blue blazers for my birthdays. My pocket money was spent on comics, like Eagle or Beano, featuring English public schoolboy heroes winning football games, and blond, square-jawed RAF aces downing Messerschmitts.

As with the Cliff Richard records, this too I outgrew in time. But perhaps never entirely. Like a memory of Eden, the aura of St. Mary Woodlands will never quite fade away. The superior Englishness represented by my grandparents will remain unattainable, and yet it lingers, as a kind of distant goal, or perhaps just a form of nostalgia.

I once introduced an American friend to my grandparents, years after they had moved from St. Mary Woodlands to a more manageable cottage nearby. It must have been sometime in the late 1970s; we had been to see a new punk rock band in London the night before. My friend, Jim, said that my grandparents were the most English people he had ever met. Their home, he said, was like something out of Agatha Christie.

And yet the Englishness of my grandparents was not as clear-cut as it seemed. For they too aspired to a kind of idyll. They also lived up to an ideal. Apart from my grandfather’s mother, Estella Ellinger, who was born in Manchester, my great-grandparents all came from Germany. As did Estella’s father, Alexander Ellinger. Her mother, Mathilda van Oven, was born in Holland. They were all German Jews. Which is to say that my grandparents, Bernard Schlesinger and Win Regensburg, were English in the way their German Jewish ancestors were German, and that was, if such a thing were possible, more so, or at least more self-consciously so, than the “natives.”

This was partly a matter of class. Already solidly middle-class in Germany, my family did even better in England, where at least one of my two maternal great-grandfathers made a fortune as a stockbroker in the City of London. It is the old immigrant story, assimilation as the sign of higher education and prosperity. Jews like my grandparents, in Germany, France, Holland, or Hungary, wanted to shed their minority status, as though it were an unsightly scar. Marks of difference— language, customs, dress, even religion, at least of the Orthodox kind—had been discarded. They wished to be accepted as something they genuinely were: loyal citizens steeped, often more so than the Gentiles themselves, in the cultures they had made their own. If anything, there was an overeagerness to do well, to speak German, French, or English more correctly, more beautifully than the Gentiles, to be more deeply versed in the literature or the music—and, of course, have finer Christmas trees.

German Jews in particular are still ridiculed by Jews with Eastern European roots for their stiff manners and highfalutin ways. The typical Yekke, as he is called in Israel, punctilious, pedantic, quick to disapprove, the type of immigrant who insists on dressing in a three-piece suit under the palm trees of the Holy Land, is a figure of fun, as well as being rather despised. It was typical Yekkes who thought the Nazis would never touch them, because they had fought in the Great War and had the medals to prove it. This type of tragic illusion was less the object of pity than of scorn.

That Yekkes often treated poorer, less assimilated Jews with snobbish disdain, as unwelcome riff-raff who would give decent civilized Jews a bad name, is beyond doubt. My grandparents were not entirely immune to this type of snobbery. The Israeli philosopher Moshe Halbertal, an Orthodox Jew born in Uruguay, once pointed out to me the important distinction between assimilated and “closeted” Jews. He disapproved of the latter. I would say my grandparents were more assimilated than closeted, although my grandmother at times had at least one leg behind the closet door.

They never converted to Christianity, at any rate, and never denied their Jewish background. My grandfather grew up in an Orthodox household; his father—a great lover of Richard Wagner’s music, by the way—had insisted on that. But there was not a trace of his religious upbringing left by the time I knew him (except possibly a hint of grumpiness on Christmas morning). Jewishness was often a topic of conversation in the family. I have no idea where the family code word “forty-five,” meaning Jewish, came from or when it was first used. But my grandmother in particular was always keen to find out whether a new friend or acquaintance was “forty-five.” Some people (all my close relations) looked distinctly “forty-five,” and some didn’t. But it was a neutral term, which bestowed no special merit, or indeed demerit, to the person under scrutiny.

To be Jewish, then, was not a source of shame. My grandparents just didn’t want to make a fuss about it, lest others might be tempted to do so. They were born in England, were educated in the usual manner of the English upper middle class: public school, in his case, and Oxford and Cambridge. They were British and had the perfect right to insist on it, and yet their sense of belonging was never simply to be taken for granted.

Their loyalty to Britain and its institutions was perhaps extreme, but it partly came from gratitude. The society in which they were born and bred did not turn on them, as Germany had done on its most loyal Jewish citizens. When there were instances of anti-Jewish prejudice, Bernard and Win, as I shall call them from now on, were usually too proud to show that it bothered them. The retired colonel in the local village, who was heard to mutter when my grandparents moved there, “Don’t like the name, don’t like the money,” was a figure of fun in the family, his words quoted as a kind of running gag at the Christmas table. And so Bernard volunteered for army service every time there was a crisis, all the way up to the Cuban missiles, when he was already in his sixties and had to be politely informed that his services to queen and country were no longer really required.

It is easy to curl one’s lip from the relative safety of a different age at their sense of gratitude. Grateful for what? Now their kind of melting into the Gentile world might be considered a form of denial, even cowardice. Why didn’t they insist on their true “identity” as Jews? But I refuse to see their lives in that light. Who is to say what anyone’s true identity is anyway? If they made a conscious choice, it was to move away from the narrow circle of their parents, the genteel Hampstead world of German Jewish immigrants, well-off, cultivated, but largely confined to their own kind. Bernard and Win were not immigrants and felt no need to seek the security of an émigré milieu. And yet certain aspects of the German Jewish background stuck with them: the worship of classical music, my grandmother’s anxiety always to be at her best, never to stick out, to avoid embarrassment at all costs, the exaggerated patriotism, and the almost fetishistic love of family, as a haven of safety.

Inside this haven, the two of them had built an impregnable fortress of their own. More than anything else, including their country, or even their own children, they adored each other. It was there, in their family of two, that they really felt safe. There is something idyllic about such rare unions, romantic and unassailable. When they died, Bernard in 1984 and Win in 1986, the family really disintegrated with them. Once they were gone, the centre did not hold.

Two of their children, my mother, who died of cancer at the age of forty-three, and Susan, who killed herself at the age of thirty, went long before them. John, mute after several strokes, died in Palm Springs, California, in 2003. Roger followed a few years later. Only Hilary is still alive, a member of the Opus Dei, after having converted to Roman Catholicism many years ago.

I sometimes go on a sentimental journey to St. Mary Woodlands. But apart from the familiar landscape, nothing of my idyll remains. The main house looks oddly cramped and is painted in a different colour, the garden looks nothing like the way it did before, and the gardener’s cottage is now a separate and no doubt expensive country home. Then there is the distant roar of traffic on the M4. I am sure it is still a lovely place for someone. But an idyll can exist only in memory.

The lives of most people, unless they were very famous, slip away into oblivion when those who still remember them die in their turn. These days few people even leave a record of their existence; whatever is there in digital form will disappear soon. E-mails are not written to last.

But Bernard and Win did leave a record, not because they wished to be immortal or even wanted others to see it, but simply because they couldn’t bear the thought of throwing it away. In the barn of John’s country house in Sussex was a stack of steel boxes filled with mouse droppings and hundreds of letters, the first of which was written in 1915, when Bernard was still at boarding school and Win was studying music in London. The last ones were written in the 1970s.

Most of them are love letters, written from the trenches in France in World War I, from Oxford and Cambridge in the 1920s, from Germany in the 1930s, from a variety of places in World War II. Often, especially when Bernard was away for three years in India as an army doctor during the war, they wrote every day, knowing the letters would take weeks, and sometimes months, to reach the other side. Even though some are missing, I don’t think that even one letter was ever consciously thrown away. They express their most intimate thoughts and emotions which were never supposed to be read by anyone else. (When her father died, Win burnt all his letters, because she believed that it would be rude to read a person’s private correspondence.) They may well have been alarmed at the thought that theirs would be read one day by their grandson, who is considerably older now than they were when the bulk of the letters were written, much less by a larger audience.

None of us have identical memories of people. We all make up stories about those we love, or hate, just as we do about ourselves. The story about Bernard and Win that I have pieced together from their letters may not have been the story chosen by others who knew them, let alone by themselves. Some might, for instance, have put more emphasis on their generosity, not just in material terms, supporting people with money, or giving thoughtful presents. Their generosity of spirit was at least as remarkable.

One story that stands out for me, as an example, is beyond the scope of this book, which ends in 1945, but is still intimately linked to their narrative as I have chosen to present it. After all their talk in wartime letters of the hateful Germans, whose targets of mass killing would, if they had been able to reach them, have included Bernard and Win and all their children, after all the news of murdered relatives, of the mounds of corpses at Bergen-Belsen, and the gas chambers of Auschwitz, after all that, they contacted a German POW camp near Newbury in 1946 to invite two of Hitler’s former soldiers to spend Christmas at their family home in Kintbury.

It was, in my aunt Hilary’s recollection, a somewhat stilted occasion. How could it have been otherwise? Too much had to be left unspoken. The immediate past was still mined with explosives, however innocent these particular Germans might have been of one of history’s darkest crimes. It was too soon for a Jewish family to celebrate Christmas with German soldiers.

But the Germans never forgot this gesture of kindness. For them it restored a sense of humanity that had been all but destroyed in the last decade. I like to think that Bernard and Win reached out to these men in the same spirit with which they rescued the twelve Jewish children. They did it out of common decency. I say common, but in fact, of course, it was highly uncommon.

There is much of this spirit in the letters. But decency is not the same thing as love, which is the main subject of the correspondence. Expressions of love, except in good poetry, when they are transformed into art, can be cloying. In fact, the love between Bernard and Win is not the main subject of this book either. Instead, I have selected passages that express how they saw themselves in relation to the world they lived in. What interested me were the stories they told each other and themselves about who they were.

Questions of class, culture, and nationality can be addressed in a scholarly way, with statistics and sociological theory. But this was of no interest to me. I wanted to find out how two people very close to me dealt with these questions themselves. They are questions I have asked myself in pretty much every book I have written. The reason is autobiographical. Growing up with more than one culture, with parents of different nationalities and religious backgrounds (I leave race and ethnicity aside), forces one to think about one’s place in the world. It is the fate of all people who feel for one reason or another that they are in a minority. If you are in the majority, you can afford to swim along with the mainstream without giving it too much thought. But a Jew in a society of mostly Gentiles, a Muslim in Europe, a black in a predominantly white country, or a homosexual, especially in places where love of your own sex is unaccepted, is forced to consider his or her place more deeply, to make up his or her own story.

This implies choice. Some of us have more freedom to choose our own identities than others, depending on time, place, and social position. I had more freedom than my grandparents. They had more freedom than people from a less privileged background, or Jews faced with more anti-Semitism.

Bernard and Win wrote to one another about their place in the world as insiders who were outsiders too, a perspective that also marks the films of their son John: Billy Liar, Midnight Cowboy, Sunday Bloody Sunday, An Englishman Abroad. By using their own words, I have contrived to produce a kind of novel in letters, with myself as a kind of Greek chorus. What emerged might not be how they would have liked to see themselves. Their portraits inevitably reflect my own preoccupations, so it should be read as a type of memoir as well. And always, in the background, like a classical score, there is the music that accompanied the lives of two very British Jews, whose favourite piece was composed by Richard Wagner as a private tribute to his wife and children: the Siegfried Idyll. It was first performed in 1870, on Christmas Day.

One

FIRST LOVE

April 25, 1915:

Dear Winnie,

I hope you won’t get bored with this effusion of correspondence. But, no,—I don’t see why I should apologize as you are one up on me & this in the shape of a letter. Moreover it is only polite to answer a letter from a lady. So “as you were” & cross all this first lot out. This brings me back to the beginning, doesn’t it & nothing said but a whole page used? That is “comme il est fait” as they say in Germany.

So begins the first letter in my possession sent by Bernard to Winnie, as he still called her then. It can’t have been the first one he ever wrote. In a letter written in 1919, he reminds her of her first letters to him, signed “Winifred Regensburg.” Winifred was a name she loathed with a passion, hence the change to Winnie, or later to Win, or sometimes Wincie, anything but Winifred.

Win in Hampstead

The facetious tone is that of the jokey schoolboy that Bernard would adopt on occasion for the rest of his life. “Ooooh, Doctor!” the cleaning ladies would squeal as he rolled the empty beer bottles along the corridor to the kitchen at St. Mary Woodlands when he was well into his seventies. He was nineteen years old when he wrote this letter. Win was a year younger.