Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

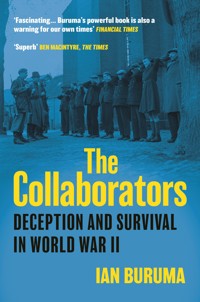

'A multiple biography with overlapping chronology is a tricky feat and Buruma pulls it off magnificently.' Ben Macintyre, The Times On the face of it, the three characters here seem to have little in common - aside from the fact that each committed wartime acts that led some to see them as national heroes, and others as villains. All three were mythmakers, larger-than-life storytellers, for whom the truth was beside the point. Felix Kersten was a plump Finnish pleasure-seeker who became Heinrich Himmler's indispensable personal masseur - Himmler calling him his 'magic Buddha'. Kersten presented himself after the war as a resistance hero who convinced Himmler to save countless people from mass murder. Kawashima Yoshiko, a gender fluid Manchu princess, spied for the Japanese secret police in China, and was mythologized by the Japanese as a heroic combination of Mata Hari and Joan of Arc. Friedrich Weinreb was a Hasidic Jew in Holland who took large amounts of money from fellow Jews in an imaginary scheme to save them from deportation, while in fact betraying some of them to the German secret police. Sentenced after the war as a traitor and a con artist, he is still regarded by supporters as the 'Dutch Dreyfus'. All three figures have been vilified and mythologized, out of a never-ending need, Ian Buruma argues, to see history, and particularly war, and above all World War II, as a neat tale of angels and devils. In telling their often-self-invented stories, The Collaborators offers a fascinating reconstruction of what in fact we can know about these fantasists and what will always remain out of reach. It is also an examination of the power and credibility of history: truth is always a relative concept but perhaps especially so in times of political turmoil, not unlike our own.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY IAN BURUMA

The Churchill Complex: The Rise and Fall of the SpecialRelationship from Winston and FDR to Trump and Johnson

A Tokyo Romance: A Memoir

Their Promised Land:My Grandparents in Love and War

Theater of Cruelty:Art, Film, and the Shadows of War

Year Zero: A History of 1945

Taming the Gods:Religion and Democracy on Three Continents

The China Lover: A Novel

Murder in Amsterdam:Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism:The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies (with Avishai Margalit)

Inventing Japan: 1853–1964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Playing the Game: A Novel

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers,Transvestites, Gangsters, Drifters and OtherJapanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo (text by Donald Richie;photographs by Ian Buruma)

This edition published by arrangement with Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Ian Buruma, 2023

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Photo credits appear on page 281.

Book design by Amanda Dewey

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83895-765-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-766-7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Hilary

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

One. PARADISE LOST

Two. IN ANOTHER COUNTRY

Three. MIRACLES

Four. A LOW, DISHONEST DECADE

Five. CROSSING THE LINE

Six. BEAUTIFUL STORIES

Seven. THE SHOOTING PARTY

Eight. THE ENDGAME

Nine. FINALE

Ten. AFTERMATH

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgments

Credits

Notes

Index

PROLOGUE

On the face of it, the three main characters in this book have very little in common: Felix Kersten was a plump bon vivant who became famous, or notorious, as the personal masseur of Heinrich Himmler, mass murderer and head of the SS. Himmler’s fond nickname for him was the Magic Buddha. Aisin Gyoro Xianyu, or Jin Bihui, or Dongzhen (“Eastern Jewel”), but best known by her Japanese name Kawashima Yoshiko, was a cross-dressing Manchu princess who spied for the Japanese secret police in China. Friedrich, or Frederyck, or Freek Weinreb, was a Hassidic Jewish immigrant in Holland who took money from other Jews by pretending to save them from deportation to the death camps, but in fact ended up betraying some of them to the German police.

In May 1947, Weinreb was about to be sentenced for his wartime behavior. A stocky, slightly stooped figure with thick glasses, he had the air of a Talmudic scholar whose mind floated high above worldly affairs. His judges belonged to the Special Court for cases of treachery and collaboration during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. The public prosecutor accused Weinreb of the most fantastic swindle ever perpetrated in his country. Defenders of Weinreb saw him as a modern-day Dreyfus, a Jewish scapegoat for crimes committed by Gentiles. Some Jews who had survived the war and known Weinreb during the occupation regarded him as a ruthless fraudster who collaborated with the Gestapo. Weinreb himself liked to compare the story of his life to a Hassidic miracle tale.

The trial of Kawashima Yoshiko, in October 1947, was a much more raucous affair. The court in Beijing was overwhelmed by huge crowds who wanted to get a glimpse of the “Mata Hari of the Orient.” Pandemonium inside the courtroom prompted the judges to shift the action to the gardens outside, where thousands more people were pressing to get in, some to find a precarious perch in the plane trees surrounding the court. Tofu and watermelon vendors were doing brisk business.

Kawashima, her hair cut short like a man’s, wearing purple slacks and a white polo sweater, was accused of betraying her native country of China, organizing a private army in support of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and spying for the Japanese in Shanghai. Her exploits as the lover of senior Japanese officers and swaggering around occupied China like a wild samurai were reported in lurid detail in all the papers. Most of her alleged misdeeds took place in the 1930s, when Japanese armies marauded across China with great savagery.

The oddest thing about Kawashima’s trial was that many of the accusations against her were lifted straight from movies, novels, and other fictions, concocted during the war by Japanese propagandists and sensation-mongers, often with her full collaboration. Kawashima was at least partly a fictional figure. The peculiar mixture of fabrication and facts resulted in her execution on a bleak early morning in Beijing.

Himmler’s masseur, Felix Kersten, was never put on trial. Born in Estonia but naturalized as a Finnish citizen, Kersten didn’t betray his country, since Finland cooperated with Nazi Germany, only changing sides quite late in the war. But Kersten was certainly a collaborator. Still, taking care of a genocidal murderer’s mental and physical wellbeing, as his masseur and confidant, was reprehensible, perhaps, but not a war crime. Kersten’s myths were largely made up after the war, when he reconstructed his past as a story of brave resistance, claiming to have used his unique position in Himmler’s court to save millions of innocent lives.

All three were what Germans call a Hochstapler. The word originally referred to a beggar who, when cornered in an awkward situation, puts on the airs of a high-class person. The usual translations in English are “fraud,” “bluffer,” or “con artist.” They were in some ways like the famous fictionalized eighteenth-century Hochstapler Baron von Münchhausen, who claimed, among other feats, to have traveled to the moon, ridden a cannonball, and wrestled a giant crocodile. They were such successful storytellers that some of their most outlandish claims were still widely believed long after the war was over, in Kersten’s case even by some highly respected historians.

As some of Weinreb’s defenders quite rightly pointed out, fraud, fake identities, made-up stories, and other forms of deceit were an inextricable part of wartime culture. Members of the resistance in occupied countries adopted false names. Subterfuge was the essential nature of their business. But the same was true of the regimes they fought. Dictatorship rules by terror and propaganda. A lie repeated often enough becomes the truth. Was it Joseph Goebbels who said that, or was it Vladimir Lenin? Conspiracy theories and other fantasies thrive when accurate information is lacking, either because the truth is suppressed or too dangerous to speak about openly. Wars offer the ideal conditions for mythomaniacs, self-invented figures, chancers who live their real lives as fictional characters, but they are not the only such conditions.

Much about the three subjects in this book seems alarmingly contemporary, at a time when a typical Hochstapler from reality TV shows can become president of the United States, when critical information is dismissed as “fake news,” and large numbers of people believe in plots and conspiracies that bubble up from the collective imagination of the internet. Weinreb, Kersten, and Kawashima thrived in World War II, but one can easily imagine them as avatars in the social media world. The conditions of war, in other words, are not so remote.

I grew up in an atmosphere thick with tall tales, boys’ stories, movies, sonorous memorial speeches, and unreliable personal memories that gave a patently bogus account of the dark war years preceding my birth. In some countries this was a matter of government policy. General de Gaulle, presiding over a deeply wounded society, where rancor over wartime behavior, in collaboration or resistance, could easily have boiled over in civil war, used his authority as a resister of the first hour to paint a picture of an “eternal France,” whose citizens had been staunch in their opposition to the German foe. This eternal France had been liberated by its own people, he claimed, its own army, with “support and help of all of France”—and, yes, of course, it had to be admitted, almost as an after-thought, also with the “help of our dear and formidable allies.” This was a myth, a falsehood, a fraud if you like.

In France, it was perhaps a necessary fraud. I was born in a country, the Netherlands, where Weinreb arrived as an immigrant from Lwów in 1916, and Kersten had lived happily and profitably before 1940, and after 1945. The Netherlands was not about to erupt in civil war. But the myth of nationwide resistance was as potent during my childhood as it was in France. Maybe this, too, was necessary in a way. Occupation by a foreign enemy is a humiliating experience. In a term that would now strike people as old-fashioned, it was as though the nation, after surrendering to superior German force in May 1940, had been emasculated. The stories of resistance, told over and over in my youth, were a way to cope with that humiliation, to regain national pride, to rebuild a patriotic spirit, to feel good about who we were, a people of heroic resisters. No doubt a similar process, just as deceptive, played out in all countries that had been under occupation.

In no country has the truth about the wartime past been more contested and elusive than in Japan. Kawashima Yoshiko is remembered as a tragic rather than a culpable figure in Japanese movies, musicals, manga, novels, and history books. Guilt can result in just as many myths as subjugation.

The sinister figure of the collabo, as such people were called in France, was an essential element in the national morality tales of the late 1950s. God cannot exist without Satan. We were aware that a minority had committed the cardinal sin of collaborating actively with the enemy. They were the fallen ones, the symbols of depravity, whose crimes served to highlight the glowing virtuousness of the plucky majority. The word in Dutch for those who opposed the Germans was goed, that is “good” or “decent,” and those who didn’t were fout, “wrong,” not just politically but morally. These were absolute categories. You were either good, or you were not. There was no in-between.

It took at least a decade for countermyths to appear, cracking the facade of postwar self-delusions. New histories, novels, movies, and television programs revealed, cautiously at first, but then with more and more vehemence as the protest movements of the 1960s accelerated, that the story of societies under German occupation had been far less heroic than we had been led to believe. It also dawned on us that the complexities of resistance and collaboration made simple morality tales of good versus evil seem inadequate, even trite.

People joined the resistance for all kinds of reasons. Some did it because they felt morally compelled by their religious or political beliefs, and some out of a sense of common (or not so common) decency. Others, not necessarily any less decent, joined because they craved adventure. Some enjoyed the thrill of danger and violence. The consequences of violent action could be severe for other people who were less drawn to adventure but were caught in brutal reprisals. For this reason, resisters often became romantic heroes after the war, long after their righteous deeds sometimes did more harm than good. In any case, active resisters were a minority everywhere.

Reasons for collaboration were just as diverse. Some of the harshest vengeance after the war was meted out to the least serious offenders, especially women who had slept with the enemy, out of desire, loneliness, ambition, pleasure in the good life, or indeed, who knows, out of love—but rarely because of any profound ideological commitment. Again, the sense of national humiliation, especially among men, inflamed the jeering crowds who humiliated these women in turn: parading them through the streets, heads shaven, covered in filth, spat on, and sometimes raped. The cruel faces of such gleeful mobs are familiar from any number of paintings of Christ’s road to Calvary. The fact that Kawashima Yoshiko was the only one of the three collaborators in this book to have been executed for what she did owed something to the violence of such emotions.

Many collaborators did far worse things than sleep with the enemy. Occupation armies and criminal regimes invariably provide a chance for all kinds of people to rise from dark corners of society and lord it over others with vengeful glee: failed artists become arbiters of official taste; petty criminals acquire fancy ranks and run prison camps; disbarred lawyers, corrupt bureaucrats, doctors with troubled histories, and marginal politicians are able to form a new elite and enjoy the trappings of high office under a foreign tyranny. This is what made the fascist years ideal for Hochstapler, fantasists who entered a world of violent make-believe. And, of course, there is often a great deal of dishonest profit to be made out of other people’s misfortunes.

But not all collaborators were gangsters, grifters, or corrupt opportunists. Mayors clung to their positions while telling themselves that resigning would open the door to successors who would surely be worse. Factory owners cooperated because they didn’t want their companies to be confiscated; and, after all, they might claim, they treated slaves from local concentration camps better than Nazi bosses would have done. Lawyers and judges acquiesced to Nazi laws and regulations citing their belief in the rule of law. To salvage their conscience, they consoled themselves with the thought that the exact nature of those laws was not up to them to determine. As for the buyers and sellers of looted properties, or providers of all manner of services to the new rulers, well, someone had to keep the economy going.

But there were also people, some of them highly educated, who believed that a new Europe, led by Germany, would stand firm against the twin evils of “Judeo-Bolshevism” and “Judeo-American-capitalism.” Such alleged dangers, usually minus the obsession with Jews, inspired similar bonds of brotherhood in Asia, where the Japanese empire embarked on its brutal campaign to liberate fellow Asians from communism, as well as from Western imperialism. The Japanese occupation of China and other parts of Asia gave rise to the same kinds of criminal types, deluded idealists, social and professional failures, vengeful brutes, chancers, businessmen, and other opportunists who operated in Europe under Hitler’s flag. But just as some people suffering the depredations and humiliations of Soviet rule cooperated with the Germans, because Stalinism seemed worse, some prominent Asians collaborated with the Japanese out of a genuine desire to rid their countries from Western colonial rule.

None of these three figures neatly fit into any of these types. Very few people, collaborators or resisters, can be reduced to single types. Human beings, even malicious or craven ones, are too complicated for that. But the highly eccentric lives of Kersten, Kawashima, and Weinreb contain elements that mark the stories of many collaborators: greed, idealism, thrill seeking, power hunger, opportunism, and even a conviction, not always misplaced, that they were doing some good.

To say that collaboration and resistance cannot be pressed into morality tales of good versus evil doesn’t mean that these characteristics are always evenly distributed. Bad things can be done with good intentions, and bad people can sometimes do good. Moral judgment has to deal with degrees. Felix Kersten certainly did some good, even as he played his role as a member of a mass killer’s court. But none of the three was utterly depraved. They were all too human, especially in their frailties. Similar frailties can be seen in many figures strutting around the public sphere today. That is why I chose to write about them, and by doing so to reflect on the question of collaboration: human weakness is more interesting to me than saintliness or heroism, perhaps because it is easier to imagine oneself as a sinner than as a saint.

Another reason for my interest in these three people is the complexity of their backgrounds. Kersten, the Baltic German, was first a Finn and then, after the war, a Swede, who lived at various times in The Hague, Berlin, and Stockholm. Kawashima was born in China, as the daughter of a Manchu prince, but raised in Japan as the adopted child of a Japanese ultranationalist. Weinreb moved with his parents from Lwów to Vienna, and then to a seaside resort in Holland, where he grew up. He died in Switzerland, a fugitive from Dutch justice and a revered dispenser of religious wisdom derived from obscure readings of the Bible.

Since the question of resistance and collaboration played such a large part in the patriotic education of my generation, it is tempting to conclude that a cosmopolitan milieu or muddled provenance would necessarily result in divided loyalties. But this is a temptation to be resisted. Multifarious loyalties don’t have to be in conflict. And an exaggerated patriotism is often the mark of a person with more than one nation in his or her background, if only because of a conviction that loyalty to one or the other needs to be proven. Whether this stems entirely from one’s own heart or is the result of social pressure is a question that cannot be answered in general terms. People may not even know themselves.

But the tangled international lives of Kersten, Weinreb, and Kawashima are not irrelevant. Emerging from mixed cultural and national backgrounds, they were swept up by world events in complicated ways. Great art can emerge from uncertain and multifarious identities, but so can more sinister forms of self-invention. I am writing this at a time of deep social and political divisions, in a society where collective identities are insisted upon, while individual identities are increasingly fluid and mixed, where a constant barrage of conspiratorial fantasies is replacing political debate, and where people inhabit not just different places but different conceptual worlds. I have chosen my leading figures, then, not as typical examples of treachery, but as figures who reinvented themselves in a time of war, persecution, and mass murder, when moral choices often had fatal consequences but were rarely as straightforward as we were told to believe after the dangers had lifted.

Hochstaplers are by definition unreliable narrators of their own stories. There is much about the lives of Kersten, Kawashima, and Weinreb that will remain unknowable. All three wrote personal accounts, but always with a particular purpose in mind: to embellish their biographies with exotic tales of adventure, or with demonstrations of great courage and gallant acts of resistance.

Of course, all memories are endlessly reedited, in the minds of individuals as much as in the histories of nations. Political fashions and new discoveries, changing tastes and shifting rules of moral conduct, all these factors affect our views of the ever-receding past. This doesn’t mean that everything is fiction, as some theorists, no less influenced by fashion than anyone else, would have us believe. There are factual truths. People were gassed. Cities were sacked. Atom bombs were dropped. We need to be reminded of these facts; they tell us much about why we are who we are. Much of what most people know about the past, however, is based on fiction: movies, novels, comic books, computer games. Collective memories are shaped by scholarship, but even more by the imagination. That is why made-up stories are worth paying attention to. They tell us much about who we are too.

The life stories of my three subjects are by no means entirely imagined. All three contain factual truths. Even critics of Weinreb admit that while he told many fibs about himself, his descriptions of daily life under German occupation often ring true. I set myself the task of telling their stories, because the facts they reveal about how people lived through some of the most horrific times of the last century are illuminating. But so are the lies.

One

PARADISE LOST

1: Helsinki

After the war, when Felix Kersten was anxious to settle with his wife and three sons in Sweden as a Swedish citizen, his previous occupation as the private masseur of Heinrich Himmler was a problem. The Swedes, already a trifle defensive about their neutral position during the war, when business relations with Germany had been profitable and useful services had been rendered to the Third Reich, were not especially keen to bestow nationality upon a man who had been in the thick of the Nazi elite.

The swift publication in various languages of Kersten’s memories and wartime notes, all heavily edited, must be read in this light. What makes his accounts especially confusing is that they are so different from one another. The Kersten Memoirs, first published in the United States in 1947, reads like a series of short essays about Himmler’s character, and his disobliging views on such subjects as Jews and homosexuals. Much of the rest of the book is about Kersten’s heroic interventions on behalf of political prisoners, the Dutch population, Scandinavians, and Jews. The Swedish translation is similar but gives conflicting accounts on various matters. The German edition omits Kersten’s most dramatic feat (dramatic, but not necessarily true): how he persuaded Himmler (and by extension Hitler himself) not to carry out a plan to deport the entire Dutch population to Poland in 1941. Himmler (so Kersten tells us) was ready to abandon this grandiose and no doubt murderous project if only Kersten could relieve his intolerable stomach pain through the magic of his healing hands. The story is of course included in the Dutch edition of 1948, entitled Clerk and Butcher (Klerk en beul ), edited and amended by a young man who had worked for the underground resistance press during the war—“good” in other words. This man, Joop den Uyl, would one day be the socialist prime minister of the Netherlands.

The picture of Kersten’s childhood, as conveyed in the Dutch edition (the others don’t go into his youth), is idyllic, almost like a fairy tale of a “good” man who loved people of all races and creeds. He was born in 1898, in Dorpat, a town in Livonia, part of Estonia, once ruled by the Swedish king, but then a province of the tsar’s Russian empire. In the sixteenth century, Kersten’s paternal ancestors had moved from Holland to Germany, where they lived as farmers until Kersten’s grandfather Ferdinand was killed by an angry bull. His widow then moved to a huge baronial estate in Livonia, where her son, Friedrich Kersten, met a Russian woman named Olga Stubbing, whose family owned quite a lot of land. They flourished, and Olga gave birth to Felix, who was named after the French president Félix Faure by his godfather, the French ambassador in Petersburg. The family had done well.

Kersten describes the sleepy environment of his childhood as a kind of cosmopolitan paradise, a cultural crossroads combining the best of everything: Scandinavian individualism, Russian grandeur, and European humanism and enlightenment. German was the dominant language of his class, but Kersten’s idea of Germany, he assures his readers, had nothing to do with Prussian militarism. Rather, it was the land of Goethe that was cherished, with its culture of “freedom, education, universality and love.” His school friends were Baltic Germans, like himself, as well as Russians and Finns. They all got along fine. And the “Jewish problem” didn’t exist at all. Kersten remembers the Jewish milliners and tinsmiths in his town with great fondness. He could still taste the delicious matzos handed out by Jewish friends during Passover. He often mused, later in life, why the whole of Europe could not be as peaceful as the lovely Livonian countryside of his childhood.

This rather pink-spectacled vision of his Baltic Garden of Eden leaves out certain things that are revealed in an admiring account of Kersten’s life, entitled The Man with the Miraculous Hands (Les mains du miracle), by Joseph Kessel, himself a fascinating figure. He was a Jewish member of the French resistance during the war, and author of, among other books, Belle de Jour, which Luis Buñuel made into one of his greatest films. Kessel, although skeptical at first, decided to believe Kersten’s stories, many of which Kessel heard firsthand. It is not immediately clear why. Kessel cannot have been naive. Kersten must have appealed to his romantic imagination. He liked heroic tales. Apart from Belle de Jour, Kessel is also the author of one of the best books written about the French resistance during the war, Army of Shadows (L’armée des ombres). Unlike his later book on Kersten, this was meant to be an imaginary account based on true facts. It was published in London before the end of the war. Fiction came easily to this superb journalistic storyteller. Army of Shadows, too, was the source of a cinematic masterpiece, made in 1969 by Jean-Pierre Melville, the great director of French gangster pictures.

Kessel paints the Estonia of Kersten’s youth as a Gogolesque outpost of the Russian empire, where the peasants would drop to their knees whenever families of Kersten’s rank passed them on the road. Kersten, he says, used to a life of ease, would have been oblivious to the misery of the people around him. He also mentions that Kersten’s mother, Olga, sang beautifully at charity parties, earning her the name of Livonian Nightingale. Her other talent was for massage. She is said to have had the power to cure people of all kinds of ailments with her expert hands, a gift inherited by her son.

The Livonian idyll came to a sudden end in the revolutionary era of the early twentieth century. Kersten writes that armies from different countries brought death and destruction to his native land, and that hatred was sown between the different peoples by their rulers. Estonia was an important base for the Russians during World War I, and Estonians first fought on the Russian side. Then, after the tsar’s regime was toppled in 1917, Estonian nationalists attempted to establish an independent Republic of Estonia. They were opposed by Estonian Bolsheviks, who wanted to be with their Russian comrades, as well as by Baltic Germans, who hoped to be the rulers of a German-dominated United Baltic Duchy. In 1918, German troops occupied the country, but not for long. They were soon replaced by Russian Bolsheviks, and Estonia became part of a Russian empire once again. Kersten’s parents lost their properties and were deported to a remote village on the Caspian Sea.

Kersten himself was in Germany when the war began. He had done poorly at school. A spoiled, lazy youth clinging to his indulgent mother, Kersten mainly took pleasure in eating too much. His reputation as a gourmand started early. As a teenager, he already looked and acted the part. His father thought he needed a firmer hand and sent him first to a boarding school in Riga, where the boy failed to shine, and then decided that he should study agriculture in Germany. This, too, was not much to his liking, but cut off from his family by the war, he somehow finished his studies and found a job on a large estate in Anhalt, in the eastern part of the country.

What happened to Kersten then is very hazy. One version—Kessel’s— has it that Kersten was drafted into the kaiser’s army, since the German government considered the Baltic Germans to be compatriots, as they would in World War II. Another book mentions a claim that Kersten won the Iron Cross at the Battle of Verdun. The author speculates that Kersten might have invented this feat himself to gain a smooth entry into the Finnish army. In yet another account, by the German writer Achim Besgen, Kersten became a soldier only when a German army, led by General Rüdiger von der Goltz, entered Finland to fight with the Finns against Russia. It is possible that he was part of a regiment of Finns in the German army, or he might have joined the Finnish army.

This was Kersten’s first experience of confused loyalties and collaboration. As a Baltic German, he was on the German side; as a subject of the tsar, he was on the Russian side; and as an Estonian, he would, at different times, have been opposed to both powers. In any event, he did take some part in the struggle for independence in Finland and the Baltic states. Collaborating with Germany would have been the best way to confront the common Russian enemy. But it wasn’t quite so simple. Finland, like Estonia, had been part of the Russian empire and declared independence only in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution. “Red” Finns, supported by the Russians, then fought a civil war with the “whites,” supported by Germany. When Kersten entered Finland and the Baltic states as an officer in a Finnish army, not only was he was fighting for independence from Russia, but he was doing so as an anti-Communist ally of Germany. Allegiance to this cause did not end with the defeat of imperial Germany in 1918.

Kersten’s military career was short. After spending much of the winter of 1918 in the freezing Nordic marshes, his legs were paralyzed by rheumatism, and he spent several months in a hospital in Helsinki. “I entered my new fatherland on crutches,” is how he put it. Again, his manner of leaving the army is controversial: he claimed that he did so of his own free will, but there are Finnish reports that say he was dismissed for forging documents to get a promotion. He was in any case now a Finnish citizen, and terribly bored. Lying in bed, Kersten watched the doctors tending to the wounded men, and, as he later recalled, childhood memories of the helplessness of injured people came back to him. He wanted to help. This would be his stated mission in life, helping the suffering and the wounded.

Massage was a popular form of therapy in Finland at the time, and one of the top practitioners was a Dr. Ekman, a major in the Finnish army, and head of the hospital in Helsinki. In Kersten’s own story, Major Ekman took one look at Kersten’s big, powerful hands and said they were worth a fortune. Joseph Kessel’s book, unusually, is slightly less dramatic. In his version, Kersten told Ekman that he wanted to be a surgeon. Ekman said that that would take years of study. Kersten was not the studying type. No, he said, grasping Kersten’s meaty palm, these hands are perfect for massaging, not surgery.

2: Lwów

Friedrich (“Freek”) Weinreb freely admits that his memoirs are subjective and that to look for factual accuracy would be missing the point. He tells his readers: “If you wish to hear the story of my life, or rather of a certain period of my life, you will have to get used to accepting strange events as the truth. However you wish to interpret them, they are true to me.”

It all began in the city of Lemberg (in German), or Lwów (in Polish), and now Lviv (in Ukrainian), where Weinreb was born in 1910. Lwów was a lively cultural center in the Galician part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. This “Little Paris,” with its Belle Epoque opera house, its grand cafés, its Viennese-Renaissance buildings, its Polish universities, its Yiddish newspapers, its Ukrainian churches, and its fine Jewish musicians, was a model of cosmopolitanism. First German and then Polish were the main common languages. Yiddish and Ukrainian were spoken as well, though not in the most highly educated circles.

“Only in Lwów!” (“Tylko we Lwowie!”) was the biggest hit song of the 1930s, known to all Poles: “Where else do people feel as good as here? / Only in Lwów . . .” The hit was sung by two radio comedians known as Szczepko and Tońko. Tońko’s real name was Henryk Vogelfänger, a Jewish lawyer, who escaped to London, where he became Henry Barker. My friend, the British journalist Anthony Barker, remembers visits as a child to the Polish Hearth Club in London, where, to the young boy’s astonishment, middle-aged ladies would swoon at the sight of his father, reliving in their minds a little bit of the lost world of prewar Lwów.

About 30 percent of the population of Lwów was Jewish, until the Germans came in 1941. In the years that followed, almost all the Jews were slaughtered, either in Bełżec, the nearest extermination camp, or in Janowska, a camp outside Lwów, where members of the National Opera were ordered to provide musical accompaniment to torture and mass shootings, before being shot themselves. There are photographs of Heinrich Himmler visiting the latter camp in 1941 or 1942. Smiling in his raincoat, full of bonhomie, Himmler shakes hands with Fritz Katzmann, the camp commander, who wrote an official report in June 1943 on “the Solution to the Jewish Question in the District of Galicia.” By the time Katzmann was finished there, 434,329 Jews had been killed. When Lwów was Judenrein, “cleansed of Jews,” Himmler ordered his SS men on the spot to make sure all traces of mass murder were eliminated.

Friedrich Weinreb remembers his childhood as “a lost paradise.” One thing that was lost, once his parents decided to flee Lwów in 1914, when Russian troops chased out the Austro-Hungarian army and people were afraid that the Cossacks were about to start a pogrom, was something that Weinreb later dismissed as a dangerous illusion: the idea that secular liberal Jews could assimilate into a humane world of reason and enlightenment. The setting for his childhood paradise was a large, comfortable, well-furnished family house in a nice neighborhood, where Yiddish was seldom heard, and the sight of bearded Jewish beggars was rare. In fact, in his recollection, Weinreb as a child had no concept of Jews, or any other distinctions based on background or ethnicity. His parents believed that this was what modern, European, civilized life was all about. German was the only language spoken in the Weinreb home. Weinreb’s father, David, who had studied business in Czernowitz, that other great multiethnic, multicultural, multilingual, multireligious Habsburg town that would lose most of its original inhabitants, had worked hard to replace his native Yiddish with the language of High Culture, which could only be German. Hermine Sternhell, Weinreb’s mother, grew up in Wiznitz, not far from Czernowitz, where Jews once made up almost 90 percent of the population. But she never doubted that their culture was German, rooted in the Germany that Felix Kersten recalled as the land of freedom, education, universality, and love. As keen members of the German Kultur, these cultivated, idealistic Jews could feel superior to the Ukrainian peasants, not to speak of the unenlightened, poor, religious Jews.

Weinreb had vivid memories of the day when his childhood world collapsed. He was on holiday with his mother in Jaremca (now Yaremche), a lovely spa in the Carpathian Mountains with gold-domed Orthodox churches and charming wooden houses. The smell of pine forest and the sweet sounds of birds and waterfalls were as unforgettable to him as the taste of those matzos on Passover in Kersten’s memories of Livonia. After a leisurely picnic in the woods, he and his mother returned by carriage to a graceful little hotel belonging to his aunt. That is when he heard the words “war” and “mobilization” for the first time. The Russians were coming. Men were being called up. Pogroms might follow. There was panic everywhere. Families were escaping in horse-drawn carts filled with everything they could carry. Weinreb’s father turned up from Lwów with terrifying tales of soldiers shooting in the streets. They found a place on a crowded freight car bound for the Hungarian border. The life of exile, of moving from one seedy hotel to another, of being an unwanted guest, of having to learn the codes of new cultures, and of viewing the past in the dense mist of nostalgia, had begun. His mother blamed the Russians and the cowardly French. She still believed in the Austrian kaiser and the civilizing influence of German culture. Weinreb claims that it was then that he had his first intimation of how cold, cruel, and stupid the world really was.

3: Beijing

Kawashima Yoshiko—or Dongzhen, as she was still called as a child—was the fourteenth daughter of Aisin Gyoro Shanqi, or Prince Su, a member of the Manchu imperial family that ruled China as the Qing Dynasty for more than two and a half centuries. She, too, had hazy memories of a charmed world that collapsed around her when she was a mere toddler. What she didn’t recall (and given her age, she couldn’t have recalled very much) was instilled in her, like a family myth, as she grew up.

Kawashima’s sparse memories of her early childhood are related in her memoir, In the Shadow of Chaos (Doran no kage), published in Japan in 1937, the year that Japanese Imperial Army troops occupied China’s major cities and committed some of their worst crimes. She starts her account with detailed descriptions of her father, Prince Su, and the Japanese man who would later adopt her, Kawashima Naniwa. A little oddly, she apologizes to her readers for spending so many words on her two fathers, but this, she says, is because she must first explain how her cossetted world was shattered by “rebellions, riots, revolutions and counterrevolutions.” Which is really a roundabout way of explaining her own story of collaboration with Japan, and the men who put her on that path.

Prince Su, a small, plumpish, round-faced man, had once been a very grand figure in the imperial court. His household in Beijing matched his high status. With a wife, thirty-eight children, and four concubines, he lived in a mansion with two hundred rooms, many in the gilded French style, with cascading chandeliers, Louis XV furniture, and a pipe organ. The compound also had several fine gardens with beautiful fountains, a well-stocked stable, and a private theater. The family had its own running water system and supply of electricity. Like all Manchu grandees, whose ancestors were tribal chieftains from the drab northeastern plains, dusty and hot in summer, and swept by freezing Siberian winds in winter, Prince Su combined elements of his Manchu heritage with high Chinese culture. He continued to wear his queue, a Manchu custom that had also been imposed on the Han Chinese, much to their loathing, and he had a romantic attachment to horse riding and falconry, but he was also a proud connoisseur of the Peking Opera, regular performances of which took place in his private theater.

The prince held a succession of important positions, in charge at various times of taxes, the police, and the Ministry of the Interior. He was a traditionalist but not in his prime a reactionary. As interior minister, he tried to improve hygienic conditions in the capital. He was responsible for such innovations as public toilets. When a plague reached Beijing from Manchuria in 1910, he made sure that bodies were cremated, and he stopped the trade in white mice, which were suspected of carrying the disease.

Although China had been ruled by dynasties that originated in the barbarian wilds beyond the Great Wall before, the Manchus had been resented as vulgar foreign upstarts from the time they took power in 1644. Loyalists of the Chinese Ming Dynasty resisted the Qing in the seventeenth century and dreamed of restoring native Chinese rule. The Taiping Rebellion in the mid-nineteenth century, led by a messianic figure who believed he was the brother of Christ and promised to lead the Chinese people to the Kingdom of Heaven, was infused with Han Chinese animus against the supposedly decadent Manchus. The uprising ended in failure, but once it was suppressed, up to thirty million people had died, often horribly. Han chauvinism also fired up activists in the early twentieth century. They were excited by Western notions of nationhood, revolution, and the Darwinian struggle for national survival. These modern ideas mostly came to them via Japan, where many of the Chinese Nationalists went to study.

In 1905, Sun Yat-sen, commonly known as the Father of the Nation, and a Christian convert, organized a revolutionary movement with Chinese students in Tokyo. His Revolutionary Alliance was supported by Japanese who dreamed of purging the Asian continent of Western colonial powers and giving it back to the Asians. Some were Sinophiles and romantic pan-Asian dreamers, some were right-wing gangsters with fascist ideals. Sun himself devised a vague set of principles, combining nationalism, democracy, and socialism, that made up his vision of China’s future.

The main reason Japan appealed to Chinese revolutionaries was its success in turning a quasi-feudal samurai junta into a modern nationstate. When, in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Japan became the first Asian nation in centuries to defeat a Western power, Asians rejoiced. Russian government propaganda described the war as a clash between Christians and Buddhists. Leo Tolstoy, a pacifist, saw it differently. The Japanese, he lamented, had learned the lessons too well from rapacious modern Western nations who had lost their spiritual bearings.

Many modern Chinese felt inspired by Meiji Japan and its Western culture in translation. Their ideals were in many ways “progressive.” Women insisted on getting a proper education and refused any longer to hobble around on bound feet (hitherto, only Manchu women exempted themselves from this custom, something that made conservative Chinese men recoil from their “big feet”). One of the women who joined Sun Yatsen’s Revolutionary Alliance arrived in Japan to escape from an unhappy arranged marriage. Her name was Qiu Jin. She liked to dress up in men’s clothes, was drawn to military action, and experimented with bombs. Back in China, she became a radical schoolteacher and entered the dense world of secret societies plotting to overthrow the imperial government. She got caught, was tried, and was executed for sedition.

Whether Kawashima Yoshiko ever regarded Qiu as a model can’t be known—she never mentioned her in her writings, and they espoused opposite causes—but their lives followed a similar course, including a taste for men’s clothes and military action. Born in 1907, Kawashima was just four years old when the Qing Dynasty came to a violent end. But the ancien régime lived on as a legend in her mind, fed by the people around her, not least her two fathers, Manchu and Japanese, who dreamed of bringing it back one day. This would continue to haunt her. Ever since she could clearly remember, she heard talk about restoring the Qing Dynasty and her family’s fortunes with Japanese help.

Prince Su was a member of the same regime that people like Qiu Jin wished to topple. And yet he admired modern Japan as much as they did, not so much because of any progressive ideals, even though he might have subscribed to some of them, but because of Japan’s growing power. Like the Japanese backers of Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Alliance, he, too, despite his questionable taste for French rococo opulence, wanted to purge Asia from Western domination, but by strengthening the Qing empire, not destroying it.

Alas for him, the empire began to unravel very swiftly in the late autumn of 1911. It began with a bomb going off by accident in Wuhan, where revolutionary agitators had been trying out explosive devices in the Russian concession area. This set the uprising in motion: Manchu officers were assassinated, revolutionaries took over cities, more and more government troops went over to the rebels.

Prince Su, like many ousted Manchu aristocrats, fled Beijing in February 1912. Disguised as a poor Chinese merchant, accompanied by a Japanese army captain dressed in similar garb, he escaped to the port of Shanhaiguan, where he boarded a Japanese naval ship bound for Port Arthur, the former Russian naval base in Manchuria, now firmly under Japanese control. A little more than a week later, the Qing imperial court ceded all political authority to the Republic of China.

Other Manchu officials fled to different parts of China, but none, except Prince Su, chose to live in an area controlled by the Japanese. The prince offered a complicated explanation. He had intended to make his way to Mukden (today’s Shenyang, the seat of the original Manchu imperial court), to reach out to the powerful local warlord. Together they would raise enough troops to topple the new republic. But his way to Mukden had been blocked, possibly on Japanese orders, so he had no choice but to go to Port Arthur. This does not sound quite right. He was probably drawn to the Japanese, because he hoped to get their support for his antirepublican resistance. He had been led up this particular garden path by Japanese friends, who fed his revanchist fantasies. To make the story even more convoluted, these friends included some of the same activists who had supported Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary project in Tokyo. One of them was Kawashima Naniwa, a pan-Asianist adventurer who would end up adopting Prince Su’s daughter as his own, which is how Dongzhen became Kawashima Yoshiko.*

Prince Su never gave up his dream of restoration and vowed never to set foot on republican soil, except under the banners of the Qing Dynasty. His children, including Dongzhen/Yoshiko, followed their father to Port Arthur on another Japanese ship, amid sobbing retainers. This is the atmosphere, thick with intrigues and betrayals, in which they grew up, pining for a world that was lost forever.

__________

*Not out of disrespect or false familiarity, but to avoid confusion with her adoptive father, I shall follow the example of other biographers and refer to her as Yoshiko from here on.

Two

IN ANOTHER COUNTRY

1: Vienna

Hitler had left Vienna two years before the Weinreb family arrived there from Hungary in 1915. A failed artist who had been staying in a flophouse and made a kind of living by drawing mawkish postcards of Viennese tourist spots, Hitler called the city a “racial Babylon.” He didn’t mean this kindly. The notorious mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, much admired by the young Hitler, had been an antisemitic demagogue who ranted for years about the “Jewish grip” on the press, higher education, the arts, and so on.

Vienna was still the capital of a great empire in 1915, but it was a decaying empire, with the hapless Emperor Franz Joseph fast losing control of Czech, Hungarian, Polish, German, Serbian, and other ethnic groups agitating for national independence. Only the Jews had no nation to agitate for, unless one includes the distant dream of Zion, and so they were the last and most loyal of Franz Joseph’s subjects. Hence the emperor’s reputation in antisemitic circles for being under the influence of nefarious Jewish interests; he was, in a popular expression of the time, “Jewified.”

Joseph Roth, the great Jewish writer born in a small town near Lwów, who became a Viennese Francophile and died of alcoholism in Paris, wrote beautifully about the question of belonging. Jews, he wrote, “don’t have a home anywhere, but they have graves in every cemetery.” Czechs, Slovenes, Germans, Hungarians, have their own soil. Jews don’t. And so, in Roth’s analysis, they would have done much better if Franz Joseph’s relatively benign cosmopolitan empire had stuck together. Roth’s best novel, Radetzky March, is a tribute to this imperial polity, the k. and k., Kaiserlich und Königlich, Imperial and Royal, also known as Kakania. The end of empire was a disaster for the Jews.

They came streaming into Vienna’s North Station, often with fake papers, or invented names to make things easier for the immigration officers, or stories that didn’t quite hold up under scrutiny. But, as Friedrich Weinreb said in the memoir of his youth: “Identity documents are untouchable, they are sacred, they are taboo.” The unlucky ones were sent back, only to return for another try with a different set of documents. The lucky ones lived in poor Viennese districts, large families stuck in one room, in cramped, filthy apartments, sewing clothes, changing currencies, peddling stuff in the streets, or selling their bodies. It was these poor Jews who shocked Hitler when he first came to the “racial Babylon.” They were the Jewish proletariat, the flotsam of empire, the unwanted gate-crashers, despised by the non-Jewish Viennese bourgeoisie, as well as the less prosperous Christians, and, perhaps even more, by members of the wealthy Jewish bourgeoisie, who viewed these Ostjuden, these impoverished newcomers from east and central Europe, in their threadbare kaftans, shabby suits, beards, and black hats, as an embarrassing and disruptive nuisance.

Elevated way above the Jewish proletariat, living in another country, as it were, high Jewish Vienna—wealthy, secular, proudly assimilated—still flourished, despite Karl Lueger’s demagoguery. Sigmund Freud gave lectures on psychoanalysis; Arthur Schnitzler wrote plays about the erotic entanglements of the upper classes; Karl Kraus was the most celebrated journalist in town; and Arnold Schoenberg, experimenting with atonal music, vowed to give the decadent French a lesson in the true German spirit—ironic in the light of what was soon to come when Germans called his atonal music an example of “Jewish degeneracy.” Schnitzler and Schoenberg were born in Leopoldstadt, a part of Vienna where many Jews lived. Freud and Kraus came from small towns in Moravia and Bohemia.

In 1922, after the war and the end of empire, Hugo Bettauer wrote an extremely popular novel entitled The City Without Jews (Die stadt ohne Juden). Two years later it was made into an expressionist film. The city is called Utopia, but it is in fact Vienna. The antisemitic government decides that Jews have too much influence and need to be expelled. But life and culture after the Jews are gone proves to be so dull and mediocre that they are asked to come back again. The novel was really a piece of wishful thinking. Shortly after the movie came out, Bettauer was murdered by a Nazi dental technician named Rothstock, who wanted to save German culture from Jewish influence. Proud of having killed the “slimy Jewish swine,” the assassin was confined to a mental institution but was pronounced “cured” after little more than a year, upon which he decided to move to Germany.

When the Weinreb family arrived at the North Station, not knowing where to park their suitcases or how to survive, about 10 percent of Vienna’s more than two million citizens were Jews. Quite where the Weinrebs thought they belonged in the pecking order was unclear, probably even to themselves. They had lived in Lwów, but they weren’t Poles, let alone Ukrainians. They weren’t Zionists or religious Jews. The harsh but warm comforts of shtetl culture were closed to them. They were loyal subjects of k. and k., when Kakania was dying. Mrs. Weinreb never stopped believing in the beneficence of Emperor Franz Joseph. And something Joseph Roth wrote about eastern European Jewish illusions about the West, the promised land of freedom, opportunity, and justice, applied to David and Hermine Weinreb as well. To the Ostjuden, Roth said, “Germany is still the country of Goethe, Schiller, and the German poets, whose works every studious Jewish youngster knows better than our Nazified high school graduates.”

Friedrich Weinreb, whose full Jewish name was Ephraim Fishl Jehoshua Weinreb, then only five years old, had no idea where he was, or so he wrote in retrospect. He was “hanging in the air.” His parents “represented a disappointed Western idealism and longed for something vague.” Quite what they were longing for is not spelled out. In the literal sense of losing their status and material comfort, as well as a home, the Weinrebs were déclassé, neither proletarian nor part of a settled Viennese middle class, and far removed from the upper class. Karl Kraus, the literary scourge of antisemites who himself dabbled in antisemitic tropes, might have made fun of Hermine Weinreb’s pretentious Germanophilia, that eminently vulnerable trait of trying too hard to assimilate, but neither she nor her husband was anywhere near to being powerful or influential enough to attract Kraus’s scorn.

Then, still holed up in a dark house on the Odeongasse in Leopoldstadt, where hungry children cried all the time, and women screamed when they heard about a husband or brother killed in the war, the child Weinreb had a kind of epiphany. That, at any rate, is how he would describe it. His father, David, a nervous and now sickly man, had been called up to serve in the Austrian army but was soon invalided out and sent to a sanatorium.

It was just when the precocious child was wondering where he belonged that his maternal grandfather, Nosen Jamenfeld, came for a visit. He wasn’t always called Jamenfeld. This was another one of those names that emerged from the lazy pen of some petty immigration officer. Benjamin Feld had been contracted to Jamenfeld. Jamenfeld or Feld came from a “dreamworld” of which Weinreb had been entirely unaware: the old world, so often sentimentalized (Chagall paintings, Fiddler on the Roof, and the like), of revered scholars of the Torah, cherished traditions, and Hassidic dances. Listening to his grandfather’s stories of illustrious ancestors and miraculous wonder rabbis, Weinreb claims that for the first time he felt a sense of security in the midst of confusion and pandemonium. Perhaps, he writes, “the downfall of the world my parents had longed for had restored the links to the world of their parents.”

From his grandfather, Weinreb heard stories full of wonder and mystery passed on by wise men in every generation. His grandmother, Channa, spoke of 127 famous sages, leaders, and scholars in her family. One great-grandfather, Avreimel, was so learned that scholars came to visit him in remote Bukovina from as far away as Jerusalem. The family also vaunted a relation to Shaul Wahl Katzenellebogen, the Jew who occupied the Polish throne for one day in 1587 because the electors couldn’t agree on any of the candidates. Even King David himself was said to be an ancient ancestor. In a bizarre but not untypical flight of fancy, Weinreb wonders in his memoir whether the power of these distinguished ancestors might now have been concentrated in him alone.

One thing seems puzzling to Weinreb, however. How could his maternal family of pious sages and scholars possibly have allowed their daughter to marry a simple man like his father, who had no leanings toward anything spiritual at all? Grandfather Jamenfeld could enlighten the boy on this matter also. David Weinreb may have been a simple businessman, but he was descended from a famous traveling preacher, the Maggid of Nadvirna, a town of great Hassidic dynasties. This teller of sacred stories possessed ancient texts with extremely difficult insights into the holy books, which can only have come from the Prophet Elijah himself. Even if these insights would never be accessible to Weinreb’s father, his son might well be the chosen one to enter their mysteries.

Weinreb had another fantasy, stemming from those difficult years in Vienna. Surrounded as he was by people in great distress about losing loved ones in the war, he dreamed that he would take them by the hand and lead them into a beautiful garden, where they would meet their lost husbands and brothers again. Meanwhile, their benefactor, after creating this miracle, would disappear into the shadows. The women, crying tears of joy, would turn to him, but he would be gone.

2: Port Arthur/Lüshun

Port Arthur was once a quiet fishing village at the tip of the Liaodong peninsula, a kind of dagger aimed at China from Korea across the strait. The Chinese call it Lüshun, the Japanese, Ryojun. Westerners named it Port Arthur in the nineteenth century, after a British naval surveyor named William C. Arthur, who fetched up there during the Second Opium War. In the 1880s, the Qing imperial government commissioned the German arms manufacturer Krupp, which had already supplied the Chinese with big guns, to fortify the village as a naval base.

During the Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japanese troops battling their way into Lüshun/Ryojun had found the heads of Japanese POWs displayed on spikes. This provoked an orgy of vengeful brutality, during which Imperial Japanese soldiers hacked, bombed, and shot thousands of Chinese to death, a macabre foretaste of what was to come several decades later in cities like Shanghai and, most notoriously, Nanjing.

When Prince Su’s family was exiled in Lüshun/Ryojun, in a two-story redbrick mansion that had once been a Russian hotel, bits and pieces of classicist and baroque-style architecture were all that was left from the period of tsarist rule. The Russians would never have been in Lüshun at all if Japan had not been pressed by Western powers to relinquish its claim to the city after conquering it in the war against China. Russia had forced the Chinese government to lease the Liaodong peninsula with Port Arthur at its tip to the tsar. Still furious over this humiliation, the Japanese took back Port Arthur in 1904, in the Russo-Japanese War, at the cost of almost sixty thousand casualties on their own side, and more than half that number of Russians. The hilly khaki-colored landscape around the naval base was littered with the corpses of men mowed down by machine guns and howitzers. Once the siege was over, the Russian fleet sunk, and the Japanese victorious, the next aim was to expand Japanese influence over the rest of Manchuria, as well as Inner Mongolia. Japan coveted the land as a buffer against Russia, as a source of coal, iron, copper, tungsten, and other natural resources for its industry, and, eventually, as a lebensraum for Japanese farmers, teachers, soldiers, artists, businessmen, architects, engineers, prostitutes, spies, and a wide variety of dubious adventurers, eager to break out of the cramped and insular borders of the Japanese archipelago.

And so, Prince Su, once the family had settled down in the former Russian hotel in Lüshun, decided to give his thirty-eight children, born from his wife and concubines, not just a solid grounding in the Chinese classics, and such vigorous Manchu pastimes as horse riding, but also a strong dose of modern Japanese learning. There is a photograph of little Dongzhen/Yoshiko that must have been taken soon after the family’s forced exile from Beijing. She looks solemn, dressed in a traditional Chinese embroidered silk robe. But people remembered seeing Prince Su’s children going to school in Japanese uniforms. Japanese teachers were hired to instruct them in language, literature, and mathematics. The household was run like a Japanese army barracks: daily calisthenics, cold baths, runs up and down the local hills in the thick snow. Soon the older children were sent to the local Japanese school, invariably dressed in kimonos. They were instructed to bow to the Japanese emperor at the start of each day.

Life cannot have been easy for a family used to having servants take care of all their needs. They, too, like the Weinrebs in Vienna, had lost their status and clung to memories of an idealized past. National allegiances became complicated. Manchus were not only out of power but no longer a coherent or sovereign people. They were simply citizens of the Republic of China, to which they felt no loyalty. But Yoshiko recalls in her memoir how her father would try to turn misfortune into a virtue.