11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

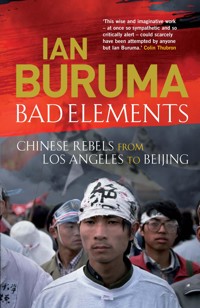

Who speaks for China? Is it the old men of the politburo or activists like Wei Jingshsheng, who spent eighteen years in prison for writing a emocratic manifesto? Is China's future to be fund amid the boisterous sleaze of an electoral cmpaign in Taiwan, or in the manoeuvres by which ordinary residents of Beijing quietly resist the authority of the state? These are among the questions that Ian Buruma poses in this enlightening and often moving tour of Chinese dissidence. Travelling through the U.S., Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong and the People's Republic, Ian Buruma tells the stories of Chinese rebels who dare to stand up to their rulers, exploring their chances of success in the face of the most powerful dictatorship on earth. From the exiles of Tiananmen to the hidden Christians of rural China, he brings alive the human dimension to their struggles and reveals the world's most secretive superpower through the eyes of its dissidents.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Bad Elements

Ian Buruma is the Henry R. Luce Professor of Human Rights and Journalism at Bard College in New York state. His previous books includeGod’s Dust,The Wages of Guilt,AnglomaniaandMurder in Amsterdam, which won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize for the Best Current Interest Book and was shortlisted for The Samuel Johnson Prize. He was the recipient of the 2008 Shorenstein Journalism Award, which honoured him for his distinguished body of work, and the 2008 Erasmus Prize.

‘Part travelogue, part political analysis, Buruma has used his insights and the remarkable confidences gained from his interviewees to build a picture of various opposition movements, highlighting their similarities and differences. At the same time, he attempts an understanding of the meaning of Chinese identity and of the relationship between Chinese tradition and the nature of modern Chinese states… Everyone interested in the politics of China and the Chinese diaspora should read this book.’ Delia Davin, TLS

‘The Chinese dissident, by contrast to the Russian, has generally been a remote figure… Ian Buruma’s Bad Elements helps make amends. The political and cultural questions which rage through it are vested in characterful men and women with shocking pasts and largely unheroic presents… Bad Elements embodies a way of approaching both Chinese political culture and the Chinese conscience. It is the fruit of dedicated travel and research, and above all of a mind too stringent to be misled – even by its own hopes.’ Colin Thubron, Spectator

‘Ian Buruma dissects the Chinese dissident community at home and abroad with sympathy yet sobriety… He does not confine his enquiry to those who have dared defy the Party in Beijing, but discusses dissent with Chinese practitioners in Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong, and goes off in pursuit of those willing to talk inside the People’s Republic.’ Graham Hutchings, Literary Review

‘A brilliant examination of who these exiles are and what has driven them to strive for democracy in a country that is seen as interested in nothing but money… Impressively comprehensive.’ Ian Johnson, Wall Street Journal

‘Detailed and perceptive, and the anatomisations of the individuals who have been the face of China’s exiled opposition is excellent.’

A. C. Grayling, Prospect

Also by Ian Buruma

The China Lover

Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo Van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism: A Secret History of Anti-Westernism

Inventing Japan: From Empire to Economic Miracle 1853–1964

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Japan and Germany

A Japanese Mirror: Heroes and Villains of Japanese Culture

Playing the Game

God’s Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers,

Transvestites, Gangsters, Drifters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo

First published in the United States in 2001 byRandom House, Inc., New York.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2002 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson and in paperback in 2003 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd.

This paperback edition, with a new introduction, published in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © 2001 Ian Buruma

‘Introduction’ copyright © 2009 Ian Buruma

The moral right of Ian Buruma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 184354 963 5E-book ISBN 978 178239 837 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Grove Atlantic LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1n 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For R. V. Schipper

Contents

Introduction

Introduction to the 2003 edition: Chinese Whispers

PART I: THE EXILES

Chapter 1: Exile from Tiananmen Square

Chapter 2: Waiting for the Messiah

Chapter 3: Stars of Arizona

Chapter 4: Mr. Wei Goes to Washington

Chapter 5: China in Cyberspace

PART II: GREATER CHINA

Chapter 1: Chinese Disneyland

Chapter 2: Not China

Chapter 3: The Last Colony

PART III: THE MOTHERLAND

Chapter 1: Frontier Zones

Chapter 2: Roads to Bethlehem

Chapter 3: The View from Lhasa

Chapter 4: A Deer Is a Deer

Acknowledgements

Glossary of Names

Notes

Index

Introduction

Much had changed in China when I wrote Bad Elements ten years after the Tiananmen Massacre of 1989. Even more has changed since then. New buildings, ever taller, ever bigger, have made cities like Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing virtually unrecognizable to anyone who has been away for longer than six months. Old neighbourhoods – what is left of them – disappear overnight, to be replaced by more and more highrises, more shopping malls, more theme parks, sometimes replicating in miniature or in painted concrete ancient landmarks that have just been razed. This isn’t just a matter of economic growth, it is a transformation.

So was I wrong to detect a whiff of decay in the authoritarian one-party state when I travelled in the People’s Republic of China ten years ago? Was I misguided in my belief that the protesters, dissidents, and free spirited Chinese who often paid so dearly for their efforts to promote a political, as well as an economic, transformation mattered?

It is not hard to find many educated, prosperous, urbane citizens in the wealthier coastal regions who will say so. The foreign traveller in China today will often be told, sometimes in excellent English, that the country is not yet ready for the democratic freedoms my ‘bad elements’ demanded. China is too big, one hears, China is too large, Chinese history is too old, the Chinese masses are still too uneducated, in fact, China is just too damned complicated for democracy to take root. The whip-hand of authoritarian government is still essential to keep chaos at bay and create the necessary conditions for prosperity to grow. Democracy, so the argument goes, is a luxury, the icing on the cake, to be enjoyed once wealth and education is had by all; first food and shelter, then, possibly, freedom.

An alternative argument, which comes down to pretty much the same thing but has a more patriotic ring to it, is that China already has its own kind of democracy, a Chinese democracy in line with native traditions and history, a quasi-Confucian system where wise and benevolent rulers act, as it were by osmosis, according to the wishes of the people. And the people, instead of indulging in selfish demands for individual rights – which might suit Western culture, but is alien to the Chinese way – believe in sacrificing their private interests for the collective good, for the good of China, for the good of a great nation with five thousand years of history.

These arguments will be expressed, usually with great conviction, while one’s attention is drawn to those tall, glitzy buildings, and those shopping malls stuffed with all the luxuries of the modern world. Look at what China has achieved in twenty years! Don’t the figures speak for themselves?

So why should it matter what such voices in the wilderness as Wei Jingsheng, who spent fourteen years in prison before being sent into exile in the United States, still say about the lack of democracy in China? Or former student leaders of the Tiananmen demonstrations, some of whom now have successful business careers in the West, and some who still languish on the margins of exile publishing and academe. After all, their voices are no longer much heard in China. Chinese born just before and after 1989 have barely heard of the protests and the killings, let alone of people who played prominent roles back then. Parents won’t talk about it lest their children get into trouble. And the children have other things to worry about, like getting ahead in the exciting but sometimes brutal world of authoritarian capitalism.

Critics of the exiled dissidents like to point out that the former protesters are out of touch with developments in contemporary China. Since they no longer live there, and most are not even allowed to go back for family visits, memories are all they have left of the country they once sought, and sometimes still seek, to change.

It is true that China has moved on since Tiananmen. But this doesn’t mean that dissidents have disappeared. New people have emerged, lawyers who bravely take on sensitive cases of corruption, environmental damage, or workers’ rights. There is even some room on the Internet, or in scholarly journals, for serious discussions about democratic theory, as long as the supremacy of the Communist Party is not directly challenged. People talk of the need for more civic rights. Commercial newspapers report on scandals, news of which travels fast through cyberspace. In a one party state, such scandals can be the closest thing to political reporting, since crime and politics are sometimes close relations.

There is doubt that personal freedoms, in terms of sexual and romantic desires, private consumption, artistic expression, and religious practices, have been expanded in China. The deal made by the ruling party and the urban middle class is politically astute. Individuals are free to do or say a great deal more than they could in the past. They can own their own houses. Up to a point, they can choose their own jobs. But organized activity, by and large, is still subject to state control, even if such control is not always effectively enforced.

As long as the state guarantees order, a number of personal freedoms, and above all, the chance for the better educated to grow more and more prosperous, most people will not demand the rights taken for granted by any citizen of a liberal democracy. In short, for the sake of getting rich people have agreed to stay out of politics.

The majority of educated Chinese, precisely the sort of people who would have been protesting in Beijing and other cities all over China in 1989, accepted the deal. So it is hardly surprising that they are often the ones who will tell the enquiring foreigner that democracy doesn’t matter, or doesn’t fit the Chinese way. Worldly sophisticates are often the first to dismiss the importance of dissident voices, or people who still argue, at great risk to themselves, that China could be different, that political freedoms must match economic freedoms, and that a one-party dictatorship is unworthy of a civilized people.

Such voices are dismissed with particular contempt, when they come from abroad, from those exiled protesters who have grown ‘out of touch.’ And the foreigner who ventures to point out China’s political shortcomings, and lament the speed with which memories of Tiananmen have been swept under a nationwide rug, can often count on a blast of sometimes peevish nationalism: who is he to comment on Chinese affairs, of which the meddling foreigner is bound to be as ignorant as he is arrogant.

Such a reaction is not always without foundation. Many foreigners are indeed arrogant, as well as ignorant, and far too prone to adopt the preaching tone of the missionary in colonial times. Yet I suspect that the quick dismissal of political dissidence is not entirely divorced from a nagging sense of moral unease about having accepted a political deal that is perhaps opportune, but not entirely honorable. Many Chinese who have gone for the money after the tragic failures of 1989 cannot really have forgotten their earlier idealism. As is true everywhere, of course, idealism fades as people grow older and set in their ways. But the spirit of 1989, the desire for a freer, more open, less corrupt society, where citizens have rights, and don’t have to lie to stay out of trouble, is surely not dead. It could be revived very swiftly if circumstances change, as they surely will; no society, certainly not China, stays the same for ever.

In fact, as I write this introduction almost twenty years after Tiananmen, the circumstances are changing already, quite rapidly. China has not escaped from the credit crisis that is ravaging the world economy. The stock market has plunged. Newly unemployed workers are returning in huge numbers from the urban industrial zones and construction sites to their villages where they won’t find much work either. The poor, often cheated out of their wages by corrupt bosses, backed by local Party officials, are certainly not going to get richer soon. Their anger often explodes in riots. But these violent eruptions are local, and can still be contained with force.

But what about the middle-class pact? The consequences of that unravelling are perhaps far greater, for it is hard to see how the Communist Party can continue in power without the backing of the educated class. Even authoritarian governments need some sense of legitimacy to survive. Ideological legitimacy, already fading fast after the horrors of the Cultural Revolution, was lost in the crackdown on Tiananmen Square. The promise of order and high-speed economic growth was the only legitimacy the Party had left, as technocrats began to replace ideologues in the leadership. Now that this promise, too, is being lost, the middle-class may not stick to its part of the bargain. They might not agree to stay out of politics for much longer.

I am as loath to predict what might happen in the future as I was when I wrote my book in 1999, but one can imagine certain possibilities. One is a traditional Chinese pattern of local rulers replacing a crumbling central power. Provincial bosses, like the warlords of a hundred years ago, might take control of their regions. They are unlikely to be friends of democracy. Or extreme nationalism might be stirred up by an increasingly fearful government, keen to deflect the energy of middle-class resentment onto foreign targets. But this is a tactic full of risk. For this, too, could follow a traditional Chinese pattern, as radical nationalism is turned against the government itself, as a punishment for its weakness. Then again, the Chinese armed forces, anxious to restore order in the unruly empire, might step in and attempt to crush all dissent.

There is a more positive alternative, however, to these old routes to violence and oppression. It has been expressed with great eloquence in a remarkable document, first signed by more than three hundred Chinese citizens, ranging from law professors to businessmen, farmers, and even some Party officials. The three hundred odd names were soon joined by thousands more. Charter 08 appeared at the end of 2008, on the sixtieth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It was drawn up as a conscious echo of an earlier charter, written by Czechoslovakian dissidents in 1977, demanding human rights in a stagnant satellite of the Soviet empire. One of the spokesman was Vaclav Havel. He spent more than five years in prison as a result.

Charter 08 is not a radical document. There are no threats of violence, or vengeful sentiments. All the signatories demand is free elections, an independent judiciary, freedom of speech, and basic human rights. But of course, in a one-party dictatorship, these demands are radical. And so one of the ‘bad elements’ I wrote about twenty years ago, a quiet-spoken intellectual named Liu Xiaobo, was promptly arrested and jailed. Others, too, were rounded up, harrassed, and interrogated. One thing is clear: dissidents clearly do matter to the rulers of the People’s Republic of China.

They matter because they have refused to stick to the post-‘89 deal. They demand to be citizens in the true sense of the word. To be a citizen is to have a political voice. Several thousand unarmed people signing a charter obviously lack the force to topple the regime. For the government to be afraid of Liu Xiaobo, and his fellow democrats, as individuals, would be absurd. But their ideas are seen, quite correctly, as a direct challenge to the legitimacy of the one-party state.

To dismiss these ideas merely as ‘Western’ notions that have befuddled the minds of a few intellectuals would be a grave mistake, and an insult to the Chinese. There is no need for China to imitate the West, or mimic its models. All the signers of the Charter want is to follow the examples of South Korea, Taiwan, or Japan, all of which have functioning democracies. The Communist Party rulers might yet be able to block the route to political freedom, but after Charter 08 (or the republican revolution of 1911, or the May 4 Movement of 1919, or Tiananmen in 1989) it can never be denied that many Chinese ardently wish for it.

Considering the alternatives, all of which would mean more violence and oppression, this desire is not only justified, and worthy of a great civilization, but the recipe most likely to result in long-term social stability, which is in the interest of all of us, in China and outside.

This is why the ‘bad elements’ still matter more than ever. Dissenters may change, new names will replace older ones, but an idea is kept alive, no matter how adverse the circumstances, an idea that may be publicly articulated by few, but is supported by many. My book was meant to pay tribute to those few, who have truly sacrificed their own interests for a collective ideal. This new edition is published in the same spirit, and as a declaration of hope that one day their sacrifices will pay off and all Chinese will live in freedom.

Introduction to the 2003 edition: Chinese Whispers

Strange things happen when Chinese dynasties near their end. Dams break, earthquakes hit, clouds appear in the shape of weird beasts, rain falls in odd colors, and insects infest the countryside. These are the ill omens of moral turpitude and political collapse. While greed and cynicism poison the society from within, barbarians stir restlessly at the gates. Corrupt officials, whose authority can no longer rely on the assumption of superior virtue, exercise their power with anxious and arbitrary brutality. When people, even those who live far from the centers of power, begin to sense that the Mandate of Heaven is slipping away from their corrupted rulers, rebellious spirits press their claims as the saviors of China, with promises of moral restoration and national unity. Millenarian cults and secret societies proliferate and sometimes explode in massive violence.

At the end of the Han dynasty, in the second century, a faith-healing sect named the Yellow Turbans caused havoc. Their leader, a Taoist priest, promised to lead his followers to “the Way of Great Peace” (Taiping Dao), and although he was killed in A.D. 184, the rebellion of the Yellow Turbans took more than twenty years to put down.

The end of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, in the fourteenth century, came after a rash of local rebellions. One of them was staged by a secret society called the White Lotus, whose folk-Buddhist leaders issued dark warnings of an imminent apocalypse. The apocalyptic theme was later picked up by another peasant messiah, a martial arts master and herbal healer named Wang Lun, who rebelled against the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty at the end of the eighteenth century. In 1900, a martial arts sect known in the West as the Boxers rose, convinced that a sacred spirit made them impervious to foreign bullets. They were wrong and died in large numbers.

The Qing was finally brought down in 1911, about fifty years after a frustrated scholar called Hong Xiuquan unleashed his Taiping army to establish God’s Heavenly Kingdom in China. He claimed to be a brother of Jesus Christ. He denounced the Manchus as agents of Satan. His crusade left 20 million dead.

Mao Zedong fitted quite neatly in this long line of peasant messiahs. Like his predecessors, he led a rural revolt to expel the barbarians, punish evildoers, and unite the empire. He abhorred superstitution, but his version of “scientific socialism” would reach the same degree of religious frenzy as Hong’s Heavenly Kingdom.

Many people in China felt that the Mandate of Heaven had slipped from the Communist Party in the summer of 1989. Once the terrified rulers had sent in tanks to crush unarmed citizens, they had lost their claim to superior virtue. Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought, which had replaced Confucianism as the official dogma and system of ethics, could no longer captivate minds, even in the Party itself. The rigid puritanism of Mao’s age had made way for the heady amorality and wild corruption of China’s new capitalism. And at the end of the millennium, a new millenarian cult had arrived, led by yet another faith-healing messiah. Most followers of Falun Gong were harmless elderly folk trying to preserve their good health through breathing exercises. Yet the government behaved as if another revolution were at hand.

Strange flowers bloom in the People’s Republic of China. They also bloom in Taiwan, the United States, Hong Kong, and Singapore. But in a dictatorial one-party state, religion fills the gaps left by the absence of secular politics. That is why meditators, tree huggers, heavy breathers, or Evangelical Christians can suddenly find themselves blown up into dangerous counterrevolutionaries. In China, every believer in an unorthodox faith is a potential dissident, whether he knows it or not. When the right to rule is justified by dogma, a moral code, a controlling worldview, and the fatherly wisdom of leaders blessed with superhuman virtue, any alternative dogma existing outside the control of the great and virtuous leaders will be seen as a mortal threat.

I believe that Communist Party rule will end in China; sooner or later all dynasties do. But when or how, I cannot say. Will one authoritarian dynasty be replaced, once again, by another, in the name of national unity and superior virtue? Or will the Chinese finally be able to govern themselves in a freer and more open society? The example of Taiwan, whose citizens can now speak freely and elect their own government, shows that it is possible. The example of Singapore, which combines relative economic liberalism with political authoritarianism, points in another, equally plausible, direction.

It was with these questions in mind that I traveled through the Chinese-speaking world between 1996 and 2001 – from the diaspora of exiles in the West, to Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the People’s Republic of China. During these years, I witnessed the “handover” of Hong Kong, the first free presidential election in Taiwan, and the beginning of the Falun Gong demonstrations in China. I saw a great deal of vitality – even optimism – on the way, especially in the economic sphere, in China no less than in Singapore or Hong Kong. But there were constant rumblings, too, a kind of background noise of angry people thrown out of work in newly privatized factories, of farmers being squeezed for money by corrupt officials, of religious believers being punished for exercising their faith in public. There was an unmistakable stink of political, social, and moral decay in the People’s Republic, the smell of a dynasty at the end of its tether.

How to describe the problem of China, with its perpetual seesaws between enforced unity, order, and moral orthodoxy on the one hand and violent religious and political mutinies on the other? It had haunted me since that summer of 1989, when so many Europeans regained their liberties while Chinese failed in their attempt to gain theirs. Perhaps I should start with three stories about walls, metaphorical and real.

In the beginning there were many walls – often little more than small fortified humps in the northern plains – which separated settled Chinese states from the barbarian nomads. But legend has it that in the third century A.D., slaves of the wicked Qin emperor pulled the various walls together to form one Great Wall. The Qin emperor was the first monarch to turn several states into one. China really began with him. The Western term for China is named after his state. We don’t actually know much about the Qin emperor. But he has gone down in history as the first great dictator, the pinnacle of a new cosmic order, who killed his critics and made bonfires of their books. Mao Zedong, a keen amateur historian, admired him greatly.

The Great Wall was never very effective in keeping out belligerent barbarians, and there are few remaining traces of the Qin. Much of the wall was built only in the sixteenth century, and even those parts are crumbling. It is more as an idea, or a symbol, that the Great Wall cast a lasting spell. First it was a symbol of China’s isolation and its rulers’ wish to control an enclosed, secretive, autarchic universe, a walled kingdom in the middle of the world. The Great Wall was seen as an expression of the Qin emperor’s dream of controlling everything and everyone in his empire. He wished to rule not only over his subjects’ bodies but also over their thoughts. The Great Wall, replicated in smaller city walls all over China – and within those city walls in even smaller walls, encircling private family compounds – stands for protection as well as oppression. One implies the other: you are controlled for your own protection; a giant prison is built for the safety of its inmates. An author from Hong Kong once wrote: “There are numerous walls within the Chinese world; the Great Wall itself merely protects the Chinese against Devils from without.”

The notion of protecting China, or Chineseness, has a long history. Chinese rebels against the Mongol rulers of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) and against the Manchus of the Qing (1662–1911) claimed to be saving Chinese civilization from the barbarians. But the Manchu emperors, too, justified their rule by acting as the self-appointed protectors of Chinese civilization; after all, they claimed to have restored order and virtue and to have unified the empire after the chaos of the late Ming dynasty. The same symbols recur in Chinese history, but their meanings can shift with time. From having been for centuries a symbol of tyranny, the Great Wall after the late nineteenth century became a positive symbol of Chinese achievement, national unity, and cultural security. France had its Eiffel Tower, and the British had their houses of Parliament; China had its Great Wall.

The dream of Chinese unity behind the protective stones of the Great Wall has not faded. The “homecoming” of Hong Kong in 1997 was celebrated by a massive ballet performance in Beijing featuring, among other set pieces, a Great Wall constructed from an army of drilled Chinese bodies, glistening with the sweat of their exertions. Large drums were thumped. Massive choruses rejoiced: The compatriots of Hong Kong were safely back inside the gates, under the protection and control of the Qin emperor’s political descendants. How the Hong Kong Chinese themselves felt about this blessing was not considered to be relevant.

In 1978 and 1979, however, another kind of wall had suddenly come into public view. It was made of gray brick, stood long and low in the center of Beijing, and was nothing much to look at, certainly not a tourist attraction. Mao Zedong had died two years earlier. After decades of total government control, a political thaw of sorts had set in, and the low wall in Beijing was quickly covered in poems, posters, letters, and proclamations, which often voiced complaints about abusive officials. In those giddy days of transition from Maoism to Deng Xiaoping’s authoritarian semi-capitalism, or “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” that unpretentious wall in Beijing was almost the only forum of free public debate in China. And it was there that a little-known electrician and underground magazine editor pinned up his poster about the “Fifth Modernization” and signed it with his name: Wei Jingsheng. Deng had announced four modernizations: in agriculture, science, technology, and national defense. Wei added democracy, without which, he wrote, “the four others are nothing more than a newfangled lie.”

It was an extraordinary thing to have done. Wei said what many Chinese thought. But to do so in public was an act of extreme bravery, and to put his own name to it was foolhardy. He had gone against the orthodoxy of the state and openly criticized its supreme ruler. He lived under a dictatorship but behaved as if he were free. As most Chinese would have expected, the hand of authority came down hard, on Wei himself and on the so-called Democracy Wall movement. Wei would spend the next sixteen years in jail, much of the time in solitary confinement, tormented to the point of madness, but never broken. The Democracy Wall movement became part of a silent history, suppressed by the government but kept alive among Chinese in exile. The wall itself was torn down, to make way for a branch of the Bank of China and a glass-paneled display promoting China’s economic progress under the benevolent guidance of Deng Xiaoping.

There is also a third wall, fictional, the wall of a prison cell. It was described by a brilliant novelist, Han Shaogong. Like many Chinese intellectuals, Han was forced to “go down” to a remote rural area after the Cultural Revolution. He spent the 1970s tilling the fields in a small Hunanese village. Out of this experience came an extraordinary novel, Maqiao Dictionary, which is a kind of spoof anthropological dissection of village life through the language of its people. Each chapter is inspired by a slang expression. One of these is “democracy cell.”

The story is told by a local gambler, whom Han springs from jail by paying his fine. Dressed in rags, his hair matted with lice, the gambler stinks so badly that Han makes him take a bath before hearing his story. Refreshed, the man starts to whine. He had been really unlucky this time.

Unlucky?

Yes, this time he had experienced the worst: a democracy cell.

A democracy cell?

Well, says the man, it’s like this: in most prisons, every cell has a boss and a hierarchy of henchmen. The boss gets to eat the best food and the best spot to sleep, and when he wishes to peep at the female prisoners through a tiny window in the wall, his cellmates must prop him up, sometimes for hours, until they buckle under the strain. But, hard though it may be, at least there is order. Every man gets his food. You have time to wash your face and to piss. You might even get some rest. Such an arrangement is better than a democracy cell. Democracy is what you get when there is no cell boss. The men fight one another like savages. They all want to be boss. Unity breaks down. Gangs go to war: Cantonese against Sichuanese, northeasterners against Shanghainese. There is no chance of getting sleep. You can’t wash. You get lousy in no time, people are injured, and sometimes even killed.

This vignette of rural prison life is a perfect illustration of a common Chinese attitude toward democracy, or indeed political freedom. Many Chinese – and not just the rulers – associate democracy with violence and disorder. Only a big boss can make sure the common people get their food and rest. Only the equivalent of an emperor can keep the walled kingdom together. Without him, the Chinese empire will fall apart: region will fight region, and warlord will fight warlord. These assumptions rest on thousands of years of authoritarian rule, beginning with the first Qin emperor and his cursed Great Wall. And they are faithfully repeated by many in the West who presume to understand China.

This is what Deng Xiaoping is alleged to have feared in 1989, when he decided to take harsh measures to stop the student demonstrations. Meeting at his walled compound with the standing committee of the Politburo, Deng said: “Of course we want to build socialist democracy, but we can’t possibly do it in a hurry, and still less do we want that Western-style stuff. If our one billion people jumped into multiparty elections, we’d get chaos like the ‘all-out civil war’ we saw during the Cultural Revolution.”

“That Western-style stuff.” A recurring theme in China, and other autocracies outside the Western world, is the assumption that only Europeans and Americans should have the benefit of democratic institutions. It is of course a theme running through European colonial history, too. But if China has a history of despots ruling over the great Chinese empire, it also has a history of schisms and disorder and disunity, of rebellions, and of brave, mad, and foolhardy men and women who defied the orthodoxy of their given rulers. Of course rebels are not necessarily democrats. But dismissing democracy as “Western-style stuff” would consign one billion Chinese to political subservience forever. That is why I approach the Chinese-speaking world in this book through the rebels, the dissidents, the awkward squad that resists authoritarianism. What is their idea of freedom? Or of China? What does dissidence mean in a Chinese society? What makes people try, against all the odds, to defy their rulers? What chance do they have of succeeding? Will those virtual walls that make China the largest remaining dictatorship on earth ever come down?

When I studied Chinese at university in the early 1970s, at the end of the Cultural Revolution, China was mostly an abstraction, as remote and physically inaccessible as the distant past. You could not go and see China with your own eyes unless you joined an organized tour of “Friends of the Chinese People” or a rigidly supervised scholarship program. For most of us, then, looking at China was an exercise in philology or semiology: you examined the official texts for subtle shifts of tone in Party propaganda, and for added information, you scrutinized photographs to observe who was sitting where at what state banquet. This kind of thing never appealed to me. I had no interest in trying to decipher the intrigues inside Mao’s court by catching the tiny rays of light that sometimes penetrated the Chinese wall. I was never a China watcher.

Yet I remained preoccupied with China, for the same reasons that I have been interested in Germany and Japan. Chinese, like Japanese and Germans – and most other peoples in fact, though not always with similar dire consequences – carry a heavy load of national mythology. Yet while Chinese have no trouble identifying themselves with China, they are often hard-pressed to explain what they mean by that. Modern Chinese nationalism, like all forms of mystical nationalism, is based on a myth – the myth of “China” itself, which rests on a confusion of culture and race. Again and again, Chinese have sacrificed themselves and others for the sake of this myth, as abstract in its way as the China we studied in the early 1970s.

During the handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China in 1997, a man named Lim Ken-han caused an astonishing fuss. Lim was the conductor of the Hong Kong China Philharmonic orchestra, which prided itself on being “100 percent Chinese,” unlike the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which contained musicians of various nationalities. Lim was furious when the latter was invited to play at the patriotic handover festivities, instead of his own orchestra, which was, in his words, “racially more suited.” What, apart from hurt professional pride, was the source of his fury? Lim was not a Communist. He was born in the Dutch East Indies, educated in Amsterdam, and went to live in China only in 1952, to help rebuild the motherland. Like so many other patriots from overseas, Lim became a victim of the Cultural Revolution. His sin was to have claimed that Western composers were worth hearing, even in China. Before he escaped to the relative freedom of Hong Kong, Lim’s patriotism was rejected in a horrible manner. For five years he was forced to clean toilets. Yet here he was in a rage because he was unable to express his love for China, or “China,” with his “100 percent Chinese” orchestra.

What, then, is the “China” that inspires such devotion? Going through some old magazine cuttings from the time I lived in Hong Kong in the 1980s, I found various expressions of “Chineseness,” all vague, all, it seems, deeply felt. In 1984, an Indonesian-Chinese wrote in a Hong Kong paper: “Back in my Southern Hemisphere, I feel the wind of the night in my face and lean out of my window, looking longingly at the stars – I pray with all my heart for the glory and good fortune of my ancestral land.” A Chinese-American expressed his sentiments in another Hong Kong magazine: “‘China’ is a cultural entity which flows incessantly, like the Yellow River, from its source all the way to the present time, and from here to a boundless future. This is the basic and unshakable belief in the mind of every Chinese. It is also the strongest basis for Chinese nationalism. No matter which government is in power, people will not reject China, for there is always hope for a better future a hundred or more years from now.” This same man described the Chinese people, wherever they may be, in Beijing, or Toronto, Hong Kong, or Amsterdam, as “an almost sacred and thus unassailable entity.”

The language is overblown, but the Chinese-American patriot managed to convey the nature of Chinese nationalism, of the myth of “China.” The religious phrases form part of the confusion. “China” is more than a nation-state, although both the nation and the state are parts of the myth; “China” is all that is “under heaven,” a cosmic idea. Even though China has been broken up into various states throughout much of its history, the ideal state of affairs is the unity of all under heaven, protected by barbarian-resistant walls. Although Chinese is not one language but many languages that can be expressed in more or less the same literary form, the myth is that “Chinese” is one. Although many races live under heaven, the majority Han race is supposed to be one, and when Chinese speak of “Chinese,” they really mean the Han; but in fact even the Han are made up of many different ethnic groups, whose origins may not even be in China. Although the cosmic state under heaven is supposed to represent harmony and order, the real state of China has been marked by thousands of years of conflict and disorder. Although Chinese civilization is a complex mixture of many cultures, both high and low, the myth has reduced it to one great tradition, roughly described as Confucianism.

“China,” then, is an orthodoxy, a dogma, which disguises politics as culture and nation as race. Order under heaven is based on “correct thinking.” Heterodoxy “confuses” people’s minds and should therefore be stamped out. The Communist Party imposed its own dogma while claiming the Chinese myth, too. Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, and, latterly, socialism with Chinese characteristics may have replaced Confucianism as the reigning orthodoxy, but those who challenge the orthodoxy – the most precise definition of dissidents – are branded as “unpatriotic,” “anti-Chinese,” or even “un-Chinese,” as well as “counter-revolutionary,” as though all these amounted to the same thing.

My general preoccupation with the Chinese myth came into sharper focus one evening in the winter of 1996, when I was asked to introduce the activist Harry Wu to an audience in Amsterdam. Wu, who lived in California, was in Europe to promote his latest book on political prisoners in China’s forced-labor camps. I met him for breakfast on the day of his talk. He struck me as a man who was driven by his cause to the point of obsession. After spending nineteen years in prison for being a “rightist” (he had criticized the Soviet crackdown on the Hungarian uprising in 1956), this was hardly surprising. While fiercely spearing his ham and scrambled eggs, he spoke about thousands of prisons and labor camps in China containing hundreds of thousands of prisoners. He spoke about the brutal struggle for survival in those terrible places. He spoke about the trade in organs plucked from the corpses of freshly executed prisoners. And he spoke about China, a “miserable country,” with venom; the Chinese people were “fanatical in their selfishness,” he said. He gobbled his breakfast up in big mouthfuls. The sound of his mouth working on his ham and eggs was all that broke, for a few seconds at a time, his tirade against his fellow Chinese.

That evening, he spoke to a large audience. Again the stories about the labor camps, the detention centers, and the prisons. Again the tales of his personal suffering and his sense of guilt at having survived, by stealing the last scraps of food from others who were starving. (Once he actually scraped something barely edible from a rat hole, thereby depriving the rat.) He finished by making an eloquent speech in favor of civil liberties and democracy.

Then it was time for questions. One man asked him about the approximate number of people who had been detained in labor camps. About 50 million, Wu thought. Someone else asked him about Mao, and yet another person about the reforms under Deng Xiaoping. Then a young woman raised her hand. She looked Chinese and I assumed she was until she opened her mouth and spoke English in a thick Dutch accent. “Mr. Wu,” she said. “We are both Chinese, and it is not easy to talk about our culture in front of non-Chinese.” Indeed, she found it painful to discuss the problems of “our Chinese culture.” But, she continued, wouldn’t Mr. Wu agree with her that democracy was an alien concept in Chinese culture? And that being so, how could we possibly expect such Western values to take root in “our Confucian tradition”?

Wu looked at her impatiently. I could see the muscles in his jaw stiffen. I can’t remember his precise answer. But he was used to this kind of thing; he heard it from Chinese-Americans all the time. In her naïve way, the Dutch woman expressed the Chinese myth, the orthodoxy, seemingly as a critic but in fact as someone who took it at face value, as though “our Confucian tradition” were a stone monument, unchanged and unchanging, as though it were the only tradition in China.

Harry Wu comes from a highly educated Catholic family in Shanghai. This alone would have made him an outsider in Communist China. He is also a damaged survivor of terrible brutality, which makes him obsessive, difficult, impatient, and perhaps ruthless. But for whatever reason, he is a man who defied orthodoxy. There are other Chinese like him, who are neither Christian nor from a background of high education. It was while listening to Wu and his Dutch questioner that evening that I had the idea of writing about “China” from the point of view of the mavericks, the rebels, and the dissidents. Their personal stories would, I hoped, help us understand the mesmerizing force of the Chinese myth as well as the reasons why some people are brave or mad enough to challenge it.

These stories took me to all parts of the Chinese-speaking world, because I wanted to show how people who shared the same cultural traditions could choose very different ways to organize their societies. Politics is never a pure reflection of some monolithic culture. There are in fact several Chinas. Seen from Beijing, Taiwan is a renegade Chinese province. Seen from Taipei, Taiwan is the legitimate Republic of China to some and the independent republic of Taiwan to others, depending on their politics. Hong Kong is now part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) but still retains its own government. Although more than 70 percent of its citizens are ethnically Chinese, Singapore is not part of China at all. But its government likes to think of itself as a model Chinese government, based on so-called Asian values, which are really more like a pastiche of Confucian values, which serve very nicely as a justification for the conservative Chinese ideal of that moral authoritarian order in which every person knows his place under heaven.

Encounters with Chinese dissidents and protesters threw up new questions. Why were so many of them Christians? Some, like Harry Wu, had Christian parents; many more had converted. Is it perhaps true, as Christians often claim, that a faith which came of age in Europe can be the only basis for liberal institutions that also ripened there? Is there something about Christianity – its egalitarianism, perhaps – that lends itself to struggles for political freedom? Or will other faiths, more in tune with Chinese traditions, provide the spur for political change? What, if any, is the connection between spiritual and political change?

This book, the product of my journeys among the Chinese awkward squad, cannot offer a definite answer to these questions. The Chinese world is changing too fast for anyone to be definite about anything. My conclusions have to be tentative. Naturally, I have my sympathies and prejudices, which reflect to some degree my own background and upbringing. Testing them in places where different norms operate is part of the fascination of travel. But my aim is not to tell the reader what to think, or to predict the future; it is, rather, to make political questions less abstract by providing a context that is nothing if not human, personal, individual. Having studied China as an abstraction in the early 1970s, I have tried to bring it alive as a society of individuals, with peculiar personal histories. If this helps readers to understand the politics of Chinese-speaking nations, so much the better. If it makes them realize that Chinese (not “the Chinese,” another abstraction) are not utterly unlike us, whoever we may be, and that freedom from torture, persecution, and spiritual or intellectual coercion is a common desire among all human beings and not merely a Western notion, it would be better still.

My Chinese journeys were not continuous. But if there is no strictly chronological logic to the journeys, there is a geographical one. I approached the center from the periphery: Beijing is the center, the last stop. From Los Angeles, then, to Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) on the fringes of China, to the final destination. This lends a certain coherence to my enterprise, but there is a political logic to it as well: as a rule, individual freedom diminishes the closer one gets to the center. The U.S. is freer than Taiwan, Taiwan is freer than Hong Kong, Hong Kong is freer than the SEZs, and the SEZs are freer than Beijing. If one imagines Chinese state orthodoxy to be a game of Chinese whispers, the greater the distance from the center, the more the message loses its power, even though faint echoes can still be heard as far away as Amsterdam.

Part I

The Exiles

Chapter 1

Exile from Tiananmen Square

We will never know how many people were killed during that sticky night of June 3 and the early hours of June 4, 1989. A stink of burning vehicles, gunfire, and stale sweat hung heavily on Tiananmen Square; thousands of tired bodies huddled in fear around the Monument to the People’s Heroes, with its carved images of earlier rebels: the Taiping, the Boxers, the Communists of course, and also the student demonstrators of May 4, 1919, who saw “Mr. Science” and “Mr. Democracy” as the twin solutions to China’s political problems. The huge, rosy face of Chairman Mao stared from the wall of the Forbidden City across three or four dead bodies lying where his outsize shoes would have been had his portrait stretched that far. Tracer bullets and flaming cars lit up the sky in bursts of pale orange. Loudspeakers barked orders to leave the square immediately, or else. Spotlights were switched off and then on again. And over the din of machine-gun fire, breaking glass, stamping army boots, screaming people, wailing sirens, and rumbling APCs, young voices, hoarse from exhaustion, sang the “Internationale,” followed by the patriotic hit song of the year, “Descendants of the Dragon”:

In the ancient East there is a dragon;

China is its name.

In the ancient East there lives a people,

The dragon’s heirs every one.

Under the claws of this mighty dragon I grew up

And its descendant I have become.

Like it or not—

Once and forever, a descendant of the dragon . . .

The words, which reduced the remaining students to tears, expressed pride in “Chineseness” as well as a sense of oppression that goes with it. The singer and composer of the song was Hou Dejian, a Taiwanese rock star who had moved to China from Taiwan in 1983, his way of coming “home,” of feeling fully Chinese. But the oppression soon got to him. So he became a kind of rock ’n’ roll mentor of the Tiananmen Movement, his last great hope for a patriotic resolution to China’s problems. When the shooting began, some students elected to die rather than retreat, but Hou talked them out of such pointless self-sacrifice, and negotiated with the army so the students could leave the Square alive. Afterward, he was forced to go back to Taiwan, where, disgusted with Chinese politics, he turned his attention to Chinese folk religions instead.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!