22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

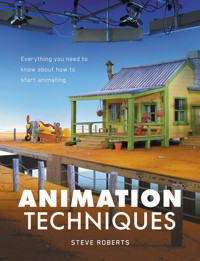

Animation can be used to illustrate, simplify and explain complicated subjects, as well as to transform stories into engaging, fantastical narratives. There are many types of animation, all of which can incorporate different artistic techniques such as sculpture, drawing, painting, printing and textiles. In this practical guide, animation tutor Steve Roberts explores the twelve basic principles of animation, demonstrating the different techniques available and offering helpful exercises for readers to practise in their chosen style. From pencils to pixels, flip books to feature films, and plasticine to puppets, this helpful book covers everything you need to know about how to start animating and will be of great interest for anyone looking to learn how to make their own animated films.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 263

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ANIMATION

TECHNIQUES

STEVE ROBERTS

ANIMATION

TECHNIQUES

STEVE ROBERTS

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Steve Roberts 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 936 5

Images from The Koala Brothers © Famous Flying Films and Koala Brothers Ltd.

Cover design by Sergey Tsvetkov

CONTENTS

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE

1 WHAT IS ANIMATION?

2 ANIMATION PRINCIPLES

3 PERFORMANCE IN ANIMATION

4 2D ANIMATION

5 PUPPET ANIMATION

6 3D COMPUTER ANIMATION

7 HOW TO MAKE AN ANIMATED FILM

8 PROMOTING YOUR ANIMATION AND WORKING IN ANIMATION

GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS

FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

INDEX

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is dedicated to the memory of Shaun McGlinchey (1962–2019), brilliant animator, inspiration and the best friend a person could have.

A huge thank you to Dee, Felix and Emily, the most important people in my life.

Thanks to Simon and Sara Bor for giving me my first job in animation.

An enormous thank you to David Johnson, Haemin Ko and Katie Chan for the case studies and the use of their images.

Thanks to Doreen Edemafaka for getting me into puppet animation and allowing me to show an image of her set.

Thanks to Adrian Gillan for being such a great life model and allowing images of him to be used in Haemin Ko’s case study.

Huge thanks to Andy Blazdell (CelAction), Dean Cesaron (TVPaint) and Ton Roosendaal (Blender) for coming up with such amazing software and permission to use images of the brilliant tools we get to use as animators.

Big thanks to Roger Todd for help with casting latex puppet heads and Rich Metson for help with Blender.

Monumental thanks to my best animating mates, Paul Stone, Mal Hartley and Vanessa Luther-Smith. I would not be who I am without you!

Finally, a gigantic thank you to Central St Martins for employing me for so long, thanks to Shaun Clark for putting up with my foibles and thanks to all the students I have ever taught. I have learnt so much more from you than you have learnt from me!

PREFACE

MY BACKGROUND

I have worked in animation for almost forty years. In that time, I’ve seen a huge amount of change in the way that animation can be produced, but the basic principles of animation have remained the same. As a child, I was fascinated by animation, whether watching it on television or at the cinema. I found it amazing that drawings or puppets could move, as if by magic.

The Do-it-Yourself Film Animation book, linked to the BBC television series, The Do-it-Yourself Film Animation Show.

When I was ten years old, there was a series on BBC television in the UK called The Do-it-Yourself Film Animation Show, introduced by an animator called Bob Godfrey. In this series, Bob showed how to do cartoon animation using various techniques, how to write for animation and how to use sound for animation. It was a complete revelation to me. I was bought the book as a present and pestered my parents for a cine camera with ‘single frame release’. Unfortunately, a cine camera that sophisticated would be incredibly expensive, so I stuck to making animated films as flipbooks in the back of my school exercise books. (In fact, I met an old English teacher of mine a few years ago and she asked me what I was doing now. ‘I’m an animator,’ I replied. ‘Oh, that figures! You were terrible at English, but I always looked forwards to watching your latest movie in the back of your exercise books!’)

In the early 1980s, I finally got to try some animation when I was doing a foundation course in art at the age of eighteen. I bought a second-hand Russian clockwork standard 8mm cine camera, built a rostrum to mount it on and had a go at doing cut-out animation. I can’t really say the results were particularly impressive, but I was hooked. However, for some strange reason I decided to do a BA course in fine art and sculpture. The problem with fine art is that you need to dig deep into your soul in order to produce decent work. Having looked deep into my soul, I discovered there was nothing there, so I dropped out of art college. I didn’t have any plan of what I was going to do next, but then fate took a hand when my mother showed me an advert in a local newspaper, asking for a college leaver to work in an animation studio.

I went for the interview, showing the artwork I had done on my foundation course and got the job. I ended up painting cells on the kitchen table of a new start-up animation company and loved every minute of it. I found that my employers, Simon and Sara Bor of Honeycomb Animation, had studied at West Surrey College of Art and Design in Farnham. Simon had been taught there by Bob Godfrey. When I learnt this, I decided to study animation at Farnham. I also worked in animation studios at the weekends and during the holidays in order to supplement my income. Since that time, I have worked on television series, adverts, feature films and short educational films. I even worked for Bob Godfrey!

The advertisement in a local newspaper that changed my life.

I started directing short animated films for the BBC in the early 1990s and in 1994 began teaching animation back at my old college in Farnham. From the late 1990s, I have specifically trained animators at Central St Martins College of Art and Design to work in the animation industry and over 600 people now have a career in animation as a result. I have devised my own class structure and worked out the best way to learn animation quickly and thoroughly.

From the late 1990s, I have used computers to produce animation, both 2D and 3D. It’s always nice to experiment with new techniques and technology, but I still use the old-fashioned lessons learnt over my career. Recently I have moved into puppet animation and produced two films using puppets and clay.

So, all in all I have had a long career in animation and I’m sure it will keep me busy for a few years to come.

ABOUT THIS BOOK

Animation and the concept of continuous moving images have been around for thousands of years, predating live-action films (an animation device powered by an oil lamp was invented in China in 150BC). In fact, you could think of live-action films as a development of animation. But as well as having existed for such a long time and involving a lot of traditional techniques, animation is also at the cutting edge of modern technology.

Animation is brilliant at explaining difficult concepts and making them understandable to all. It can put over stories in an engaging way, ranging from being realistic to completely fantastic. Almost any artistic technique – for example, sculpture, drawing, painting, printing, textiles, flower arranging and make-up – can be incorporated into animation. If you have a visual style or artistic technique, you can animate with it.

There is always something new to learn about animation and you will never know it all. In order to make an animated film, you need to do lots of research and will end up finding out a lot about the world around you.

This book will go through the basics of animation in Chapters 1, 2 and 3. These incorporate the twelve rules of animation along with suitable exercises to illustrate these rules. Chapters 4, 5 and 6 will go through the different techniques of animation and you can try the exercises in your chosen animation style. The last two chapters will go through how to make a short animated film and how to get it seen by an audience.

Some people believe that animation is very expensive and takes a long time to do, but if you have a great script and keep the technique simple, you can produce an entire, amazing film on your own that will look magical compared to a live-action film. If you want a worthwhile hobby or a fulfilling career, animation has it all.

1

WHAT IS ANIMATION?

Many people have tried to sum up what animation is and it is consequently open to several different interpretations. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, animation means to ‘Breathe life into; enliven, make lively’. This is a rather general interpretation of the word. For a more specific definition, the world’s largest animation festival (Annecy International) defines it as ‘Any audio-visual animation, created frame by frame whatever the technique, made for the cinema, television and any other screening platform may be entered.’

What’s clear here is that animation is something that consists of a series of images played one after the other in order to create movement, each of those images being partly or completely created by some method.

A recreation of an early human being creating a cave painting with movement.

The one thing that animation relies on is the persistence of vision. This is where the light receptive nerve endings in the eye continue to see an object, even after the light has ceased to be emitted from the object. It means that if we see a succession of images that change slightly from image to image, it will create the illusion of movement. This is helped by a ‘shutter’ which will create a millisecond of black between each image in order to help the eye register each picture.

A SHORT HISTORY OF ANIMATION

In order to understand animation, we need to look back in history to see its origins.

If we go right back to the first images created by Homo sapiens, often those images were there to help capture movement. Early cave paintings depict animals with multiple legs, giving the impression of galloping. Centuries later, Greek vases depicted athletes going through sequential images of the sports in which they were engaging. During the Renaissance in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italy, Leonardo da Vinci created sequences of motion with drawings in his amazing and copious collection of sketches.

A recreation of a Greek vase showing sequential movement.

A Chinese inventor and craftsman called Ding Huan invented a device that created movement from a series of paintings on a cylinder, which was hung over an oil lamp and the heat of the lamp caused the cylinder to rotate. When the images were viewed through the slits of an umbrella type device, they would appear to move. This was invented in Han Dynasty China around 150BC.

The Ding Huan device used to produce animation – the first of its type.

Many centuries later, Joseph Plateau invented the Phenakistiscope, also known as the Spindle Viewer, in 1832. The Phenakistiscope was a disc split into equal segments, with an image drawn on each one. This was mounted on a stick. Slots were cut into the disc and the images would be viewed through the slots while holding the disc up to a mirror. When the disc was spun quickly, looking at one segment at a time would cause the images to create motion. The slots created a shutter between the eye and the images.

The Phenakistiscope (or Spindle Viewer) was invented by Joseph Plateau in 1832 as a way of causing images to create motion.

William Horner invented the Zoetrope in 1833. The Zoetrope consisted of a cylinder with slots in the side, balanced on a spindle. Inside was placed a paper strip of drawings, each showing a slight difference from one image to the next. Once the cylinder was spun, looking at the pictures through the slots created the illusion of movement. The slots acted as a shutter between each of the images.

The Zoetrope, invented by William Horner in 1833. When the cylinder was spun, the images on the inside of the cylinder came to life.

The first flip-book animation appeared in September 1868 and was patented by John Barnes Linnett, under the name Kineograph. This consisted of a series of drawings displaying frame by frame movement, stapled together in a stiff book and the pages flipped one after the other by the thumb. (You can make something similar with a pad of sticky notes.)

A flip book made from sticky notes (using the same principle as patented by John Barnes Linnett).

The Mutoscope (or a ‘What the Butler Saw’ machine). This was invented in 1894 by Herman Casler.

A more elaborate version of this was called the Mutoscope (or a ‘What the Butler Saw’ machine). This was invented in 1894 by Herman Casler. A sequence of images on cards was mounted on a drum and viewed though a small peephole. A crank was turned to rotate the drum and show each image, one after the other. The images were taken from film and then printed on to the cards.

In 1877, Eadweard Muybridge developed a system of creating sequential photographs of animals and humans that displayed their movement in accurate detail. He was financed in this endeavour by Leland Stanford, a wealthy race-horse owner. He also created the Zoopraxiscope for projecting these sequential photographs in 1879. Not exactly animation, but providing lots of information for animators. His books Animals in Motion (1899) and The Human Figure in Motion (1901) are still in print today and are well worth buying by any budding animator.

A series of images similar to those captured by Eadweard Muybridge.

At the same time in France, Charles-Émile Reynaud developed the Praxinoscope, which was an improvement on the Zoetrope, using light and glass mirrors in order to improve the animation of the images. He also invented the idea of projecting animation on to a screen. His Théâtre Optique device consisted of 300 to 700 gelatin plates (with images hand-painted on them) mounted in cardboard frames and taped together, and incorporating perforations to register against the gear wheels they ran around. A light would project through the images on to a screen and it created a soft, blurred impression of animated movement. In many ways it was also a development of magic lantern shows, which projected still or puppet-like movement images on to a screen. His invention could be thought of as the first ever cinematic experience.

All of these earliest examples of the moving image could be considered ‘animation’, so in many ways live-action film could be regarded as an offshoot of animation, not the other way round. Inspired by Eadweard Muybridge, in 1899, Thomas Edison created the Kinetoscope (though it was developed by his employee, William Dickson). It was a precursor to the ‘What the Butler Saw Machine’, where the movie was viewed through a peephole. It relied on a thin piece of film that ran past the eyehole, through a series of gears with a light to illuminate the film. Edison and Dickson developed the Kinetograph, a sophisticated (for the time) cine camera to shoot the movies.

One of the first uses of film to produce projected motion can be ascribed to the Lumière brothers. Auguste and Louis Lumière are considered the first ever movie makers. They both worked for their father, who was a pioneer photographer and photographic platemaker. Auguste and Louis developed machines that would mechanize the platemaking process. Later on, they set to work to make a film camera and projector. They acquired the rights to Léon Guillaume Bouly’s Cinematograph (a combined film camera and projector) and incorporated it into their own device. These were demonstrated in 1895. Their films consisted of documenting real life and none was more than a minute long. The first film shows workers leaving the Lumière factory. The brothers never developed their system and refused to sell their cameras and projectors to any film-makers. They spent the rest of their careers developing colour photography.

THE HISTORY OF DIFFERENT ANIMATION TECHNIQUES

Drawn Animation

Probably the first ever drawn animated film was Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (using a chalkboard and cut-out technique) by James Stuart Blackton in 1906. Blackton was a comic artist, a ‘chalk talk’ music hall entertainer and a journalist with an interest in new technology. He interviewed Thomas Edison about his new invention, the Vitascope (a form of electric projector), and Edison invited Blackton to draw him as they were filmed with his new, hand-cranked, camera. When Blackton saw the film, he noticed that at certain points of the movie the drawn line would suddenly get longer. This happened when the camera had stopped filming, but Blackton had continued drawing. This intrigued Blackton. He was most impressed and bought a camera, projector and several prints of films from Edison. These films were incorporated into Blackton’s stage shows.

A chalkboard music hall act, which led to some of the first film animation.

One of the earliest films Blackton produced was The Enchanted Drawing (1900). This was more a demonstration of one of his stage shows than an animated film. He drew a wine bottle on a piece of paper, then the drawn champagne bottle turned into a real bottle of champagne. Obviously at this point they stopped cranking the camera and substituted the drawing for the real bottle, before cranking the camera again. This led to further experiments and Blackton worked out that a certain amount of rotation of the crank of the camera would result in one frame of film being exposed.

Humorous Phases of Funny Faces was drawn on a blackboard with chalk and the lines rubbed out and redrawn in order to move them, cranking the camera slightly between each of the drawings. The film consisted of a man smoking a cigar, then a man and woman looking at each other and the man then blowing cigar smoke in the lady’s face. There is also a sequence involving a clown and a dog, with one arm and one leg drawn on black paper and moved (paper cut-out animation).

The first animated movie drawn entirely on paper and shot on film was Émile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie of 1908. This film was made as a series of ink drawings on paper but was shot on negative film. It gave the impression of being white lines on a black surface, like chalk on a blackboard. It is likely that the camera would have been placed on some kind of rostrum. The camera would have been facing down, so that the drawings could be placed under the camera and shot one at a time more easily.

Another pioneer of animation was Winsor McCay. He did not invent animation and used basic techniques to produce his films, but he elevated animation to a form of high art. His first film, Little Nemo, made in 1911 is an amazing piece of animation and displays a wonderful sense of performance and movement, combined with the greatest artistry. His film was even coloured by hand and has a beautiful, ethereal quality.

Up to this point 2D animated films had emphasized the magic of drawings moving. They were not trying to be anything other than a collection of drawings and something that was created by hand. From here, there were further developments. Light boxes and a paper registration system were used so that the previous drawing could still be seen.

Around 1913, the Bray Studio in New York developed the use of cellulose acetate sheets. The characters were traced from the original drawings on to these sheets so that the background behind the character could be seen, rather than everything having to be shot on one sheet of paper. This made shooting a scene more complicated, so more sophisticated rostrums were developed and also things called exposure sheets (or dope sheets) on which to record the shooting information. (The Bray Studio made more money from the patent of this technique than it did from making cartoons.) The studio also divided the labour up into the different processes of creating a cartoon: animating (an animator would create key drawings and mark the timing on a dope sheet); in-betweening (an assistant animator would take the animator’s key drawings and do the drawings between each of these keys to create smooth movement); tracing (the drawings would be traced on to the acetate sheets); and painting (a painter would colour in the characters on the reverse of the acetate sheets). A background artist would paint the backgrounds. A camera person would shoot the backgrounds and acetate sheets, combined, one frame at a time. An editor would cut the film together, ready to be printed and sent out to cinemas. All of this led to drawn animated films being made more efficiently.

Walt Disney used one of the early synchronized sound systems (Pat Powers’ Cinephone system) in order to make one of the first sound cartoons, Steamboat Willie (1928), staring Mickey Mouse. This really revolutionized animation. Sound is almost 50 per cent of what is taken in when viewing an animated film. Walt Disney Studios was also the first animation company to secure the rights to use Technicolor, a three-colour film process, which really put the company ahead in the cinema. The first Technicolor film was Flowers and Trees (1932). Around this time, Walt Disney Studios began developing storyboards, which greatly added to the narrative structure of animated movies.

Walt Disney Studios also developed the use of the multiplane camera, which gave depth of field to a movie, creating a richer image. The first film to use this was The Old Mill (1937). It was also used to great effect in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

From this point on, drawn animation stuck to these basic principles for the best part of sixty years. The exception was the introduction of the Xerox process at Disney, which meant that a lot of money could be saved on the tracing process and a more accurate vision achieved of the drawings created by the animator. The first film to use this process was One Hundred and One Dalmatians made in 1961. It was only in the early 1990s that drawings were scanned into a computer and coloured on screen.

Each piece of technology added to the illusion that these were more than drawings moving and were the real living expressions of an artist’s imagination.

Stop-Motion

James Stuart Blackton may also be responsible for the first ever stop-motionanimated film, The Humpty Dumpty Circus (1898). In this film a collection of circus animal toys performs for a group of children. Unfortunately, only a few stills of this ground-breaking film exist.

Some of the earliest stop-frame animation involved the animation of matches.

Another contender for the first puppet animation is possibly Matches: An Appeal (1899 or 1914) by British film-maker Arthur Melbourne Cooper. This is a rather hotly contested one! It was an advert for the Bryant & May Match company, thought to have been made in 1914 to encourage people to buy matches for soldiers on the front line during World War I. However, it has been suggested that it could have been made for soldiers serving in the Second Boer War in 1899. It consisted of figures made of matches, jointed by wire, playing football and cricket and writing the appeal on a wall.

Amongst the many films made by Cooper was Dolly’s Toys (1902). This consisted of a group of toys that came alive while their owners were not looking (predating Toy Story by nearly 100 years)! A film with a similar theme was Dreams of Toyland (1908), where a boy and his mother went to a toy shop and bought lots of toys. When the boy went to sleep, he dreamed that his toys came alive. They engaged in several fights and ended up with a major car crash! Generally, most early puppet films involved inanimate objects coming to life in a magical way.

In Lithuania, Władysław Starewicz made several films as Director of the Museum of Natural History in the city of Kaunas. From this, he conceived the idea of making films with dead insects, jointed with wire. His first fictional animated film was Lucanus Cervus (1910).

Generally, stop-motion animators were very secretive about their techniques, none more so than Willis O’Brien, who made the animated sections in the feature film The Lost World (1925). O’Brien was very coy about what he was doing and how he did it. He was probably the first person to use jointed armatures and latex rubber to create realistic-looking animals and dinosaurs. Based on the Arthur Conan Doyle book, this was the first feature film to use puppet animation. O’Brien animated the dinosaurs and they were shown as if they were the real thing. When O’Brien disappeared into his studio, he shut everybody out in order to keep his techniques secret. He went on to animate the star of the feature film King Kong (1933).

King Kong was animated by Willis O’Brien in 1933.

Early 3D animation was mainly done in wireframe and computers were not fast enough to play the animation back. Wireframe models constructed in the computer consist of wire-like edges for each shape, with no area coloured between the ‘wires’.

It would seem that drawn animators were open about what they were doing and the fact that their films consisted of drawings moving, like a kind of magic. They would also emphasize the huge amount of work involved and how many drawings had to be made to produce the movies. On the other hand, puppet animators tended to keep their techniques secret and tried to give the impression that what they were doing was the real thing and not animation at all. Dolls or matches had magically come to life, or ‘real’ dinosaurs were filmed in some exotic location. Early 3D computer animation also had a similar mystique!

Computer Animation

Some of the earliest computer animation was produced using military plotting applications. These produced abstract shapes that would morph from one thing to another. An early example can be seen in the title sequence of the Alfred Hitchcock film Vertigo (1958), animated by John Whitney.

In Canada, Peter Foldes made Metadata in 1971, using a computer that could calculate a metamorphosis from one plotted drawing to another. These images were then printed out, shot on a conventional rostrum camera and played back on film.

In 1972, Ed Catmull and Fred Parke produced A Computer Animated Hand at the University of Utah. This is one of the earliest examples of 3D computer animation. Some of this animation was used in the feature film Future World in 1976. Later, Catmull, Parke and John Lasseter went on to form Pixar with Steve Jobs.

So many advances have been made in 3D animation that it is almost impossible to document them all. The ability to articulate joints, the lighting, the rendering and shading of images and the use of motion capture (the interpretation of a real actor’s movements to an animated character) are just some of the amazing advances that have been made.

We now have the prospect of animating and making films in virtual reality, using headsets. Animation has always relied on the latest technology, whether it was creating optical-illusion based toys, or using cellulose acetate sheets, engineered armatures or the computer.

WHERE TO USE ANIMATION

It is true to say that you can do anything with animation.

Sometimes the reason for an animated film existing is to show off the design style of the illustrations used. Animation tends to work better where it is used to do something that can’t be done with live-action movies. If it can be done with live action, it’s going to be much easier and look better if real people act out the plot. Animation can take you beyond everyday life.

Animation is great for recreating something that doesn’t exist or can’t be filmed. It has recently been used a lot in documentaries to fill in the gaps where live-action footage is unavailable. Sometimes it can be cheaper to commission animation, rather than buying archive footage.

Anything fantastical and imaginative will work well in animation. This is particularly true of Manga-style films, which cover fairly realistic people put into fantastical situations. If a film is well scripted and performed, it does not take long for an audience to suspend its disbelief and become engaged with the story.

The anthropomorphism of animals has always been a popular theme for animated films. In the early days it was the easiest way to get an animal or inanimate object to display life. What could be more amazing to an audience than to have an animal or an object behaving like a human being! The first real animated movie star was Felix the Cat. His creators (Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan) were originally inspired by Charlie Chaplin and other early comedy film stars, but pushed this slapstick humour into a whole new surreal world, where the most amazing things could happen. Felix was dealt a fatal blow by the noisy Mickey Mouse, with Felix gaining sound far too late to compete. These early animated films were not just aimed at children, but at a much wider audience. They were also lauded by leading intellectuals and artists of the day. Walt Disney was considered an artistic genius.

Animation can also be used to illustrate, simplify and explain complicated subjects in a way that viewers will understand. This may range from basic ‘explainers’ for how to use a piece of the latest technology, to governments detailing their latest pieces of policy. You will see huge amounts of animation on Facebook, putting over different points of view, or delivering ‘fake news’.

Animation is also great at selling things. Most adverts have some kind of animation in them, even if they are not fully animated. This could range from simple moving graphics or moving lettering, to special effects inserted into a live-action movie, or even to a full-on mini-animated feature.

Animation has been used in lots of multimedia events, such as projection on to buildings and large-scale video screens. It can make the ordinary seem fantastic.

So, keep your mind open and think about what you want to do with animation!

WHERE TO SEE ANIMATION

The best way to see animation is to go to animation festivals, or to film festivals that have an animation section. There may be an animation festival near you; various websites list animation festivals all over the world. At these festivals, you will get to see some of the latest animated films, long before anyone else. It is good to understand the breadth and scope of what animation can do and all the different styles that are used nowadays. It is worth noting that the latest animation produced by individuals tends not to be available on the web. A lot of animators will keep their movies to show at festivals first and when they have done their ‘festival run’ will release them for open viewing to the world by the internet. This is usually about two years after the first release date.

Browse websites like YouTube and Vimeo. Often, you can come across some little gem that may be a few years old, but that you find really inspirational. A fantastic place to see some revolutionary animation is the National Film Board of Canada website. The National Film Board of Canada has been producing ground-breaking animation for over eighty years and most of its output is now free to watch.