2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

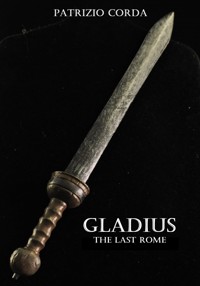

- Herausgeber: Patrizio Corda

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

465 AD. - In the years leading up to the final fall of the Western Roman Empire, young Aphranius Siagrius finds himself inheriting his father Aegidius' rule, a now Roman-Barbarian kingdom

covering much of northern Gaul and completely disconnected from the rest of the empire.

As the years pass, Syagrius helplessly witnesses the unraveling of a world he had believed to be eternal.

But the misfortunes of his era will not make him desist from pursuing his greatest dream.

Now an independent ruler, the man who went down in history as “King of the Romans” will find, inspired by the idea

of a great of the past, a way to bring a defunct Western empire back to life.

Clinging desperately to that intuition of his, the only hope of having a future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Aphranius Siagrius. The Last Eagle

Indice dei contenuti

APHRANIUS SIAGRIUS. THE LAST EAGLE

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

XLVII

XLVIII

XLIX

L

LI

LII

LIII

LIV

LV

LVI

LVII

LVIII

LIX

LX

LXI

LXII

LXIII

LXIV

LXV

LXVI

LXVII

LXVIII

LXIX

LXX

LXXI

LXXII

LXXIII

LXXIV

LXXV

LXXVI

LXXVII

LXXVIII

LXXIX

LXXX

LXXXI

LXXXII

LXXXIII

LXXXIV

LXXXV

LXXXVI

LXXXVII

LXXXVIII

LXXXIX

XC

XCI

XCII

XCIII

XCIV

XCV

XCVI

XCVII

XCVIII

XCIX

C

CI

CII

CIII

CIV

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THANKS

Literary property reserved ©2024 Patrizio Corda

APHRANIUS SIAGRIUS. THE LAST EAGLE

Patrizio Corda

To my mother

Major cities and fortifications in Britain in 410 AD.

I

The enigma

Arles, June 458 AD.

"Aegidius, bring me the boy."

Surprised by that sudden request, Aegidius nodded and immediately rushed down the stairs.

He broke into the large forecourt of the residence, where Siagrius was busy overseeing the drill of the buccellarii placed to guard the entire perimeter.

He laid his hand on his son's shoulder.

"Caesar desires your presence," he announced to him transfixed.

Upon hearing those words, Siagrius stiffened and gave himself a look.

He was drenched in sweat, and was in a state not at all befitting an interview of that importance.

He quickly restarted his hair, blond and slightly curly, wiping his forehead with the sleeve of his robe. Then he began to climb the steps with his heart in turmoil.

He found the emperor, Julius Valerius Majoran, sitting in the space he had set up as an office for that sojourn.

The latter had always loved Gaul more than Italy, to the point of fomenting the rumors of the malignant who believed he was even interested in transferring his rule there, to the detriment of Rome.

As soon as he had arrived, he had arranged for a desk to be set up right on the terrace of that recently restored old residence. From there it was possible to enjoy a splendid view of the Rhone River. He had to admit that that expanse of pearly water, calm and kissed by the summer sun, was a splendid setting.

It was a picture that encouraged more the idleness of the ancients than the fervent and feverish work for which Majoran was known. Indeed, all around him was a swarm of secretaries and young lawyers.

Indeed, one of his fixed nails had always been the revision of laws, which during the chaotic reigns of his predecessors had accumulated contradicting each other and in fact nullifying each other.

On the minds of those green and bright associates of his depended the outcome of the restoration he so hoped for.

Not even 40 years old, the august man was a man who was already beginning to show signs of that wearisome activity.

Wavy, straw-colored hair was whitening along his temples, and sleepless nights spent studying and making plans had left large purplish bags under his eyes.

Nevertheless, the emperor, with his gentle features, delicate oval and always friendly demeanor, naturally inspired good-naturedness and confidence.

Had it not been for the purple he wore, it would have been a feat to recognize him as the holder of ultimate power in what remained of the glorious Western Roman Empire.

As soon as he saw him, Majoran gave him a radiant smile that contrasted with the fatigue that made his face look so drawn.

He cordially motioned him to come closer.

Siagrius mentioned a bow.

"Holy august one, I am here as you have requested. I ask you to forgive my horrible appearance."

Majoran laughed amiably, putting down the documents he held in his hand.

"An aspect that fully reflects the dedication to the work you have been assigned. How could I possibly resent that? Now sit down."

Siagrius timidly obeyed.

The emperor remained silent for a few moments, his gaze fixed on an indefinite point.

"The sky and water are so similar in appearance, yet they are different, sharply divided. So are the West and the East. However hard they try to claim absolute supremacy, aspiring to encompass within them the whole world, this will never be possible. Never. They will never be able to prevent..."

"Prevent what?" interrupted Siagrius.

How had he allowed himself?

Interrupting the august one as he granted him the honor of listening to him!

Perhaps that was why he kept calling him a boy: although he was about to turn twenty-eight, he had not yet learned to restrain himself, merely following orders.

Something in which his father, magister militum for Gaul, excelled.

A fundamental attitude in order to get ahead.

He bowed his head, mortified.

But Majoran seemed not to have noticed his recklessness. He kept his gaze fixed toward the horizon.

At that moment a seagull, an unusual presence for that place, swooped down toward the water, lapping at its surface.

"This is what I mean," resumed the emperor, pointing to the scene. "Neither we nor the Eastern Empire will ever be able to oppose those who for centuries have been knocking on our doors and crossing our borders, driven by the instinct to survive. Just as it will never be possible for the birds to stop plying the skies and gliding over the waters."

Siagrius looked at him interdicted.

He had failed to understand the analogy between two such vast and powerful political realities and two among the kingdoms of nature.

Majoran realized his bewilderment, and gave him another of his usual, affable smiles.

He shook his head, as if scolding himself for being so abstruse.

"You don't have to fret, Aphranius," he heartened him. "The time has not yet come for you to look at the world in a certain way. One day, you will understand."

"I beg your pardon, sacred august," he said embarrassed.

"Nothing to forgive, boy. Now go on, and go back to your drills. I have great confidence in your work, with which I am already satisfied. You are indeed your father's worthy son."

Flattered by those words, Siagrius took his leave with a bow.

But before returning to his duties, he turned around one last time.

He saw Majoran hunched over his papers, the river in front of him.

And he thought back to that last smile of hers before he dismissed him.

Good-natured, almost fatherly.

But with a tinge of concern and disillusionment that left him deeply troubled.

II

The future of the Empire

Arles, June 458 AD.

That same evening, Siagrius decided to indulge in his usual walk around the city. It was really hard for him to give it up. After a long day spent practicing and coordinating the buccellarii charged with presiding over the residence of Majoran, getting lost in the streets of Arles was ideal for relaxing the body and mind.

Following the emperor on that short journey had given him the opportunity to visit many places, but none of them could ever compete.

Like so many other times, he stopped in front of the splendid amphitheater building, a true jewel of the city, even more striking under the evening sky near sunset.

Everywhere on the streets of Arles it was possible to breathe in the infectious vitality of its inhabitants. People filled the markets, talked in the open air, and continued to engage in the arts and culture.

Most of all, they loved living, with a carefreeness that instead concealed an awareness of the precious gift they had been given.

He certainly could not have said the same about Italy.

Majoran had inherited a catastrophic situation, the child of political uncertainty and an unhealthy environment in which figures less and less worthy of the purple had followed one another to power.

This had come to be reflected in the embarrassing neglect they had observed during their brief journey. Roads, once the pride of the empire, defaced by ditches and wild grass. The monuments of the past in a state of neglect, reduced to shelters for wretches or worse still to veritable urinals.

The statues scarred, either by alleged churchmen who feared arcane demons were hiding in them, or by poor men looking for material to work with or resell.

In all those circumstances he had seen the august man seething with rage and growing livid in the face. He had heard him complain, indignant and hurt, about the unworthy state of what remained of the greatest domain in history.

Passion, perhaps more than a sense of duty, moved Majoran.

And they were moving after him.

He decided to get lost in the busiest streets of the city.

In Gaul there seemed to be no perception of what was happening at such a short distance. He had heard from his father that, however, compared to the past, Arles itself had shrunk in size.

The world was becoming depopulated.

The population centers shrank, and the distances between them grew.

But the citizens of Arles were smiling.

They bought merchandise, laughed, kept good taste in dressing. The colors and scents were everywhere, and they were calling him all the time.

He would have been happy to live in such a place.

It seemed an avuncular reality to the woes of the world, an island protected from the negative things surrounding it.

Beyond those walls, people were becoming savages.

The number of uneducated people was growing, and young people often aspired to be athletes or warriors, unaware that such paths could be taken in conjunction with a minimum of training.

Ignorance was rampant and consequently encouraged the spread of superstitions. It benefited monks and members of the Holy Church, who took advantage of it to precept new adherents or to ingratiate themselves with rich widows, guaranteeing access to the kingdom of heaven in exchange for substantial donations.

The imperial coffers also did not allow for helping the tens of thousands of needy in the Urbe alone. That task had ended up falling to the very Church, which had gladly accepted it, aware of the immediate return in terms of popularity and influence.

He was sorry to pass such judgment on the Lord's ministers, but so be it. His father, as a true military man, had never paid much attention to spirituality, and had raised him accordingly.

He decided for that evening to extend the route.

Not one of the great monuments of Arles escaped his sight.

The Baths of Constantine, the Forum, the Circus erected under Antoninus Pius.

Impressive yet aesthetically mind-blowing structures.

Even in Gaul, the echo of Rome's greatness resounded crystal clear.

By the time he had finished that splendid wandering, night was approaching.

With legs heavy but spirit refreshed by immersion in those pulsating streets brimming with life, he set out for the imperial residence.

He continued to look around ecstatically.

Could a place like that, so prosperous and happy, have survived even when surrounded by an oppressive reality that only cast ominous omens for the future?

He hoped he would.

The venture into which the Caesar they were serving had precisely the goal of avoiding what seemed irreparable.

The slow agony of their world, a putrescent and grotesque body that had been dragging on for centuries.

Perhaps, as Majoran had told him, the time had not yet come for him to ask such questions.

He was still young.

He could not, after all, claim to already predict what would happen in the future.

But that did not tear him away from the apprehension that gripped him.

Because that future, so near and gloomy, would be the one in which he would live.

III

One hope

Arles, June 458 AD.

Siagrius watched his father finish his dinner in silence.

Although already well over forty, Aegidius retained the vigor of a young man. He possessed an incredibly robust physique, which would have been said of a man in the prime of life were it not for the network of wrinkles that already scourged his sun-baked face of a thousand campaigns. He wore his blond hair very short, and his strong, hunched septum nose gave him a perpetually serious air, although his brown eyes, always alert, actually concealed the irony typical of old-fashioned warriors, devotees of the camaraderie spirit among soldiers.

Aegidius became aware of his son's gaze.

He read there the desire for answers.

He guessed about what.

"I know what you're thinking."

"Me?" asked Siagrius, taken by surprise.

"Of course. You are my son. I notice that you are trying to hold back concern about what you have seen in the last period. Well, I want you to take it easy. We are in good hands."

"But I would never dare to question Caesar's talents."

"I know it well," nodded Aegidius, drinking his wine in one gulp. "Let me tell you a little about the man to whom we swore allegiance. Majoran is a nobleman, a senator and the son of senators. But above all, he is a Roman. A true Roman, just like us."

To Siagrius that seemed a stretch. He knew full well that his father was a native of Lyons, and that he was related to the same Siagrians who had given the empire the well-known senator from whom he had taken his name. They did not have a single drop of Italic blood in their veins. In the eyes of true ancient Romans they would have seemed barbarians, like any other people living outside of the Urbe. But he dared not object.

"But although he is a nobleman, he has retained the legalitarian spirit of his ancestors. He does not tolerate stealing, injustice or abuse of power. And he knows the value of memory. That is why he cares so much about the monuments of the past, even though he is a Christian."

"I noticed," said Siagrius. This was an understatement, to say the least: not infrequently, Majoran had even gone so far as to slip into unflattering judgments about the Holy Church.

"And he is not only a politician and an expert in economics and agrarianism, all of which someone like me understands nothing about. He was also an excellent general in his youth. Not for nothing did the great Aetius want him on his side when he faced Attila and his terrible Huns at the Battle of the Catalauni Fields. In that confrontation, the august was one of those who distinguished himself most. And yet, when Valentinian's folly deprived us of the leadership of Aetius, he had the humility to step aside without claiming anything. The transparency of his soul and his honesty were unparalleled. Unfortunately."

"Why do you say that, father?"

Aegidius sighed bitterly.

"You see, my son, when Aetius died we all feared the worst. The last defender of the empire, the man who had driven out the invincible Attila was gone. We were defenseless. The barbarian peoples who had rushed to Rome's aid only in the name of respect for Aetius would return to undermine the borders. This was what we expected, and in fact numerous provinces were lost. But then, Majoran arrived. He did not ask for the purple, mind you. It was fate that gave it to him, believing that the time had come for the turning point, for rebirth."

Aegidius had fought that same terrible battle with Majoran, and was like him very attached to the figure of Flavius Aetius, the late general who had saved the empire.

But Valentinian III's envy and fear had cost him his life.

Whenever he talked about it, Aegidius would end up getting mad, and then his eyes would get moist. It was like that that time, too.

"Caesar is a gift from the Lord. He is our last chance to save the empire. Because no one will help us. You saw, too, how long it took Leo, emperor of the East, to recognize him. Only by relying on him can we rise again, and get rid of the invading barbarians. You know what? Majoran may be even better than Aetius. He may not be as formidable a general, but politically he is much more lucid. Although..."

"What?" urged Siagrius.

"Too honest," Aegidius said, lapidary. "He loves justice to the point that he does not understand that it sometimes comes through less than exemplary actions. Do you think everyone loves him unconditionally just because he is the new augustus? I remind you that in Gaul he is not at all well liked. Everyone here still mourns the former emperor Avitus, who owned half of Auvergne. Not to mention the Church and Pope Leo. Nevertheless, Majoran hopes to convince everyone with good government. I wonder why. He knows very well too that by now, patriotic love and moral rigor are utopias, relics of the past."

Such was his father's disillusionment that he threw Siagrius into sorrow.

Although he was a young adult, he retained the swinging and easily provoked emotionality of adolescents.

The image of that august man animated by good intentions but unable to guard against his enemies disheartened him.

Making him doubt the possible success of his plan.

"But then..."

"Then it will be up to us to do what he fails to do," Aegidius reacted vigorously, pride in his own role in his eyes. "Caesar is alone against everyone. And it is our duty to help him. Remember, Siagrius, that his cause is ours. On the outcome of it depends the future of us all. We fight for the man. And we must preserve him. At all costs."

That emotional and heartfelt speech by his father was enough to restore Siagrius’ lost confidence.

The security of being on the right side.

Next to the only emperor worth dying for.

IV

Insidia

Rome, July 458 AD.

He had locked himself in his office in the heart of the Lateran Basilica.

He didn't want to see anyone. And he did not want anyone to see him like that. The first among God's servants on earth could not show himself in the grip of the basest and vilest human feelings.

But so it was.

Letting go on his own seat, Pope Leo closed his eyes, clenching his fists as tightly as he could.

He would have liked to pulverize those feelings with the force of his hands. Instead, he was forced to deal with them.

Forced to face the reality of the facts.

He felt belittled.

That's what it was.

Diluted by a ghost, and that new and insignificant face.

Flavius Aetius.

They were still talking about him!

People still praised him as a demigod. Perhaps they forgot that it was he who had stopped the demon Attila, shown him the crucifix, and foretold the wrath of the apostles if he dared to violate the Immortal Urbe. Did they no longer remember him?

Had they already forgotten the days of the sack of Rome, when it was only through his intercession that the Vandals had not slaughtered the population?

The same population he had provided for!

Was one fact of arms enough to erase everything he had done?

He did not deserve it.

In addition, he now had to deal with another character who seemed to have every intention of limiting him, of relegating him to the role of a mere ecclesiastical official, as if even God's will had to bow its head before the motives of politics.

The new augustus, Julius Valerius Majoran.

Not for nothing, a former general of that damned Aetius.

His name had come completely new to his ears. He had never heard of him. Until the time had come for their first interview.

He expected a dumbed-down old man, interested only in the clamor of the purple and not in making it a real instrument of government.

Instead, he was confronted by a young man in the prime of his life with a decidedly rare intellect.

A nobleman who seemed to have the welfare of the people at heart.

But above all, a mind he had failed to read.

This infuriated him, and he had to restrain himself from punching the desk with all his might.

It had been a cordial but vacuous dialogue, a continuous succession of ritual formulas and catchphrases that extolled the communion of purpose between empire and church for the good of all.

But when he had looked into his eyes, he had been unable to understand.

Was he lying, or was he really serious?

Did he really intend to raise the empire? And how, then?

Initially he had thought him clueless, a person absorbed in that glorious but now uninfluential role almost by accident. As Avitus had been, for that matter.

Then, however, he had reverted to a feeling he had hoped never to experience again.

Diving into those eyes, it had seemed to him that he was groping in the dark, that he had not the slightest certainty to hold on to.

Unable to understand whether he was facing a subject, an ally, or even worse, an enemy to defend himself against.

Exactly what he had felt every single time he had dealt with Aetius.

Could it have been?

Who was this Majoran, in truth?

Was he really that honest, to the point of almost looking like a fool, or was he hiding something else?

When that interview had ended, he had come out of it interjected and upset.

But most importantly, defeated.

For of one thing he was certain.

The emperor understood this, while he did not.

That's where that irritation came from, that envy, that animosity that felt natural, such as he had not felt in a long time.

Majoran understood how much he valued the primacy of his Church, the status he had managed to confer on it, and its position in the collective imagination of an increasingly uncouth and ignorant people.

He had guessed his plans, his aspirations.

His prediction of an empire that, close to collapse, would end up relying in all things on him, the voice of God on earth.

He, on the other hand, had not been able to get the slightest idea of the man with whom, from there on, he should try to have at least a civilized relationship.

In order not to make an exceedingly dangerous enemy, given the consensus he enjoyed in Rome, both among the wretched and the noble.

But the truth was one, he confessed to himself in tremors.

And it was that Majoran, for him, was already an enemy.

Whatever he really wanted.

In the dimness of that room, Leo felt as if stripped of his ecclesiastical vestments.

He had become overwhelmed by emotions, and the worst ones at that.

Without manifesting the slightest desire to oppose it.

Reframing man.

And by virtue of this, feeling terribly unstable.

His position was no longer as secure as it used to be, when he had been convinced that he had become indispensable. That much was certain.

But he would do anything to become one again.

V

Friends and enemies

Surroundings of Sinuessa, August 458 AD.

They all found themselves back at camp, exhausted but with hearts swelling with excitement and pride at the outcome of that confrontation.

After a succession of bitter humiliations, culminating in the ignominious sack of Rome three years earlier, the empire triumphed again. And it did so precisely at the expense of the Vandals, those who, led by Genseric, had violated the City of the Apostles.

It had been a lightning-fast descent and conducted at a forced pace, theirs.

As soon as he had learned of the Vandal landing in Campania, Majoran had immediately ordered all the forces in his retinue to march.

Forces he had personally led.

Although outnumbered and mainly composed of barbarian mercenaries his troops, with Aegidius the executing arm of his insights, had routed the enemy.

Not content, Majoran had ordered the survivors to be pursued as they tried to return to the ships with the loot. Carnage had ensued, as well as the recovery of much of the stolen goods.

Several dozen Vandals had been captured and had come to the camp naked, beaten, and chained. As much as he disliked such filth, the august one had allowed these to be the object of his men's mockery and insults.

They would have been resold as slaves, thus giving a little respite to the suffering imperial coffers. Most importantly, they would have paraded wherever they went.

A strong message needed to be sent to the population.

The empire was now ruled by a finally worthy augustus, skilled in both politics and military maneuvering.

Anyone since then would have to deal with it.

At the risk of ending up just like those Vandals.

Siagrius, still electric from the adrenaline of the fight, rushed off his horse and dashed under the large tent where the emperor had gathered his generals to praise them.

Among them, he glimpsed his father. Tired yes, but completely unharmed.

It was yet another test of courage in his glittering career.

Unfortunately for him, just then Majoran decided to retire to his quarters to indulge in some rest.

Aegidius came to meet his son, taking him under his arm.

"Father, we have won!" he told him in exaltation.

Aegidius barely smiled, leading him into their tent. Once inside, he let himself go to the ground with a thud, visibly tried.

"Yes, it's true. We won, at least this time."

Siagrius helped him undress his lorica, and handed him some water, which his father drank greedily. Then he knelt beside him.

"I was thinking about something, father," he said doubtfully.

"To what?"

"It's true, we won and it will surely resonate throughout Italy all the way to Urbe and Ravenna...but I was wondering why..."

"...why us?"

"Exactly," Siagrius admitted, disappointed in his predictability. "I mean, the troops of the patrician Ricimerus were stationed in the peninsula anyway..."

Aegidius emitted a contemptuous grunt. He stood up again, his bare, imposing torso shiny from sweat.

"This is quickly said. Majoran may be a man of almost unnerving honesty at times, but he is no fool. The truth is that he does not trust Ricimerus at all."

Siagrius looked at him stunned.

How could an emperor not trust his own patrician, the most prominent military figure under him, the designated protector of the most precious borders, the Italic ones?

"Do I need to remind you who Ricimerus is?" made Aegidius without hiding his contempt. "He is a barbarian. But that is not the issue. As excellent a commander as he is, nothing about him inspires confidence. And the august one knows this well, because he served together with him in the army. He knows that the Swabian is not a man to be trusted completely. There is no loyalty in his heart. And he also knew that leaving him alone in Italy for too long could harm his consent. Ricimerus can never rise to the purple because of his impure blood, but he could put someone else in a position to do so, if he had sufficient time and space. Don't you think so?"

Siagrius had never thought about it.

In his mind still unaware of the vileness to which ambition could lead, he had always believed that the imperial hierarchies were upheld by a crystalline, absolute and inviolable loyalty.

This, despite what had happened to past emperors.

"You must remember," Aegidius added with a sigh, "that the faction opposed to Caesar is not limited to the conspirators in Gaul or Genseric with his Vandals. Other enemies move in the shadows, and they are closer than we think."

"So Father, do you think the emperor catapulted himself here to Italy so quickly because he suspected something?"

"No. I don't think he suspects anything yet. There is no evidence, after all. However, we could call it a preemptive descent. That is. Majoran is not maneuverable, and Ricimerus knows that. He would never agree to be an august puppet. But someone else might like the compromise. That's why we came back here: to reaffirm the soundness of his position."

Although overwhelmed by that endless amount of information and background, Siagrius nodded decisively.

He was now clearer about the context in which they were moving.

A reality that was finally being revealed to their eyes, with all its evil plots unfolding in the darkness.

A reality with one man at the center, surrounded by enemies.

A man they should have had their backs to.

Whether he liked it or not.

VI

The gamble

Ravenna, October 458 AD.

Ricimer could not contain his astonishment at what he had heard. His crystalline eyes snapped open, two large, shining gems in a hard, snow-white face, contrasting with his long raven hair and thick, bristly beard.

He looked at the emperor. He seemed paler than usual.

He tapped his fingers against the armrest of his seat.

He could not tell if he was nervous about having to give them that news, or something else.

After all, he had always resented Ravenna. He had more than once called it, in moments of confidence, a city designed for lake creatures and not for men.

He resolved to break that increasingly heavy silence.

"Truly you will not take me with you, holy august one?"

"No. We feel that your presence at the moment is more useful in Italy, Patrician."

The pluralis maiestatis. This meant only one thing.

He was no longer talking to Julius Valerius, the young nobleman with whom he had shared a career in the army. Now, he was facing the august Majoran.

And that forced him to accept that verdict without the right to oppose it. He simply bowed his head.

"A few weeks ago I sent the trusted Aegidius and his son Siagrius to Gaul. The goal is to reestablish the supremacy of the empire in that province, which has long reasoned as an independent entity. After that it will be the turn of Spain, which we intend to take back as soon as possible. But above all, Patrician, there is another reason why it is necessary for me to go to Gaul as soon as possible."

Leaving me here to handle the grits, Ricimerus thought.

"It needs me to show myself to those people. They need to know who the new augustus of the West is. I would be a fool if I believed that those people do not still mourn the late Augustus Avitus. It is necessary that I gain support even there, where my candidacy has been publicly opposed."

Ricimerus wrinkled his nose at the memory of Avitus.

Perhaps Majoran forgot that it was the two of them, joining forces, who had deposed that incapable man.

And now he talked about it as if he had been a holy man, a martyr.

Even the idea that he was turning to Spain did not exalt him.

There now reigned the Visigoths. A people to whom he owed half his own blood. The prospect of their extermination sent him into a rage.

"Sacred august one, if I may say so," he said then, in a cavernous but deferential tone, "this is a journey not without danger, for you."

"I can't afford to stay here," replied Majoran piquantly, in a completely unprecedented tone that shocked Ricimerus.

He was witnessing his ultimate transformation.

From an educated and quiet man to an august one capable of unexpected authority.

To his detriment, to boot.

"As you well know, Aegidius settled in Arles just in time before the Visigoths themselves laid siege to it. It is of paramount importance that he obtain reinforcements. And I myself will be the one to bring them to him. At the same time, I am concerned that Italy be well protected in my absence. And no one would know how to do this better than you, who of all are the only one worthy of my unconditional trust."

He was trying to tame him now.

He understood.

And even Majoran knew that he had noticed.

They knew each other all too well.

Ricimer felt he was at the center of a play.

An act in which he played a completely marginal role.

"My duty is to obey you, sacred august one," said the Swabian then, bringing his hand to his heart. "May the Lord watch over you, and grant you a smooth journey."

Majoran nodded, and dismissed him with a wave of his hand.

He watched Ricimer leave the room with a martial, machinelike step. His back bent, his gaze on the ground.

He closed the doors and remained seated with his gaze lost in the void.

What they had said to each other had been entirely superfluous.

It was what they had not said to each other that was far more important.

He knew he was taking a huge risk.

Ricimerus was a formidable general, even more so than Aegidius.

There was no one in the entire empire who was his equal.

But unfortunately, in his heart dwelled unbridled ambition, a lust for power without end or demeanor.

The exact opposite compared to him, who also made it to the purple.

And he knew that for the patrician, the impossibility of reigning was still an open wound. He was obsessed with domination.

He would have done anything to succeed, directly or indirectly.

But that did not change the reality of the situation.

He was forced to travel to Gaul.

What he had said was true. He needed their consent, and it was essential for the continuation of his journey that those people stop mourning Avitus and decide to support him.

With the empire's richest province under him, he would have the resources to begin the reconquest of what Rome had lost.

And that mattered more than anything else, even the remote possibility that Ricimer took advantage of that absence to maneuver behind his back, seeking support among people hostile to him.

And he knew how many there were, waiting for his misstep.

He sighed.

By now the decision had been made.

He only hoped that he would not have to regret it in the future.

VII

Honor

Arles, February 459 AD.

"I therefore officially appoint you, Aegidius, magister militum for all Gaul. Let this be the just reward for your sincere loyalty, of which I am honored to boast."

Siagrius was beside himself with happiness.

At last, after a lifetime of sacrifice, terrible battles he had survived, and travels around the empire, his father reached the pinnacle of his own multi-decorated career.

Now, Gaul would have been militarily under his control.

He was officially one of the most important and powerful men in the entire Western Empire.

He looked at his father.

His eyes filled with tears, his lower lip trembling but smiling as he had never seen him in his life.

Aegidius made to bend down and hug Majoran's knees.

But the latter disliked such gestures, and urged him to hold him in an embrace that smacked more of friendship than political alliance.

The roar of applause resounded in the audience hall of the palace of the decurions of Arles.

Only then did Siagrius remember that he was in the presence of the most important figures in the empire and beyond.

That was not just Aegidius's day.

With that ceremony, Majoran had shown that he had finally succeeded in winning the goodwill of the nobility of Gaul, the same people who had been hindering him, perhaps even conspiring against him, out of respect for the memory of the late emperor Eparchus Avitus.

The evil things that had been said about him up to then were swept away by invocations to the emperor, to his light shining throughout the empire, good news in view of the imminent rebirth of their world.

One of the august's ministers informed everyone present that the celebratory banquet was ready, requesting that each of them take their respective places. For that occasion, Majoran had spared no expense, and he made sure that all those who came to the palace that day could enjoy something that met their usual tastes.

For there were not only Romans and Gauls in that hall.

Far from it.

Siagrius looked at his father from a distance, still moved, and wondered if one day he would ever match his greatness. Would he be able to embody as he did such ancient and sacred values as loyalty, valor, and total dedication to his Caesar's cause?

Aegidius was loved by everyone in Gaul. Further north, in Soissons, he owned a variety of properties, and whenever they returned there it seemed as if the augustus himself had arrived in town.

Who knows if he would ever get the same respect.

"Doubt not, young Siagrius," thundered a voice behind him, speaking in rough, marked Latin. "If that is what you ask, you will live up to it someday. I have heard very good things about you."

At that moment, the weight of a large, strong hand weighed on his shoulder. Siagrius turned, and met a hard but friendly gaze. A tall, slender man was watching him with amusement. He wore a thick brown beard and wore a bright green suit with gold edges. A large gold stud shone on his belt.

King Childeric, ruler of the Salian Franks, a federated people of Rome.

Embarrassed, Siagrius stiffened and sketched a bow.

"My lord, it is an immense honor for me to know that you even know my name."

Childeric smiled, showing off a row of very white teeth.

"Word gets around, my friend. Especially if a noble Roman makes his case in battle, as you did."

"A Roman of Gaul I might add, Your Grace," intruded a second voice, shrill and clucking.

Turning around, he saw who had spoken.

No less a person than Sidonius Apollinaris, the very famous poet, had intervened in the discussion. One of the most famous and acclaimed nobles in all of Gaul, he had initially been opposed to the rise of the august being married to Avitus' daughter. Only later had he changed his mind, even going so far as to compose a panegyric in his honor.

Even more distressed, Siagrius addressed a bow to him as well.

"The noble Aegidius can well say that he has a son worthy of his worth, who is not for nothing recognized throughout the empire."

"I...thank you," Siagrius managed to mutter.

Everywhere were laughter and echoes of amiable conversation.

It was as if concord, good feelings and a natural optimism could only reign around Majoran.

Even delegates from allied barbarian ethnic groups were present, as were prelates and nobles who came from all over Gaul and Italy.

The investiture of Aegidius had been the preamble to a meeting of the most important figures in the empire that the augustus intended to revive.

In a corner, Siagrius recognized another figure.

He was a young man, about the same age as her. He wore beautifully made clothes, and his bearing, like the snow-white skin and gentle features in his face, suggested that he was a nobleman.

Her brown hair was barely longer than fashion indicated at the time, with a fringe that almost hid his eyes.

He saw Sidonius embracing him warmly, and he understood.

It seemed impossible.

That peer of his was none other than Ecdicius Avitus, the son of Eparchus Avitus, the augustus whom Majoran himself had deposed along with Ricimerus. He would have expected to meet anyone that day but him!

His presence was a confirmation of what he had already guessed.

The Augustus had definitely drawn the nobility of Gaul to his side, to the point where he could boast of having the son of his unfortunate and deceased predecessor at his own table.

Ecdicius noticed that he was staring at him, and gave him a cordial greeting followed by a barely-there smile.

Siagrius remained motionless, even though he realized he was completely out of line.

But he still could not believe it.

Not even dispelled by the joy of his father's personal triumph, within moments he had heard himself praised first by a king and then by the empire's most famous scholar. To top it off, one of the richest scions of Gaul, the son of a former emperor, had recognized him.

There was no doubt.

While happy for Aegidius' victory, he had to recognize that Majoran had achieved an incredibly greater and more significant one for all of them.

He had now officially recaptured Gaul.

Which meant there was still hope.

The empire could survive.

And he would have done it with their august, if they would have been able to protect him from the thousands of pitfalls that still lurked in the shadows, determined to bring him down.

VIII

Africa's gold

Carthage, December 459 AD.

He had brought order back to Italy, and to Rome to boot.

The same Rome into which he, four years earlier, had quietly entered, taking the Palace of the Caesars. He had plundered that city of everything, heedless of the admonitions that had been made to his people for centuries about violating the Urbe.

Then, just as quietly he had returned to Africa, laden with loot, leaving behind what was now no longer the hub of the empire, but an empty shell destined to disappear.

He had then stayed there in his new domain, waiting for the empire to come crashing down to take what little was left of it.

But like some grasses, capable of growing even in the driest soils, a man had emerged, almost from nowhere.

And he had gathered Rome under himself. Then Italy.

In disbelief, he had even seen it defeat the skepticism of the Gauls. The empire, now surrounded by barbarian tribes, had slowly recovered. He had even managed to drive his Vandals out of the South and Sicily.

And now he was about to make Spain his own.

From there he would sail in command of a fleet, he had heard.

A fleet with which he would attempt to retake Africa.

His Africa, the one he wrested from Emperor Valentinian III in a deal that humiliated Rome.

There seemed to be a higher force behind the new august one.

Nothing seemed to stop him.

He had tried in vain to send ambassadors to them to seal a truce. They had returned empty-handed.

Since then, day after day, Genseric had grown darker, more worried. He had locked himself in a silence that he broke only to attack anyone who bothered him, reviving his famous and feared outbursts.

He was afraid.

Limping from a bad fall from a horse in his youth, he wandered aimlessly through his rooms. Any seat was uncomfortable for him, and he ended up walking again.

He massaged his large dark mustache under his prominent nose.

He had to admit this to himself.

He was no longer facing the wimpy emperors of whom he had easily been right: Valentinian, Petronius Maximus, Avitus.

That Majoran was made of a completely different stuff.

And he would probably have won at that rate.

Gripped with paranoia, he had even ordered his people to start poisoning wells in coastal locations, fearing his landing at any moment.

He looked at his own reflection in the dirty glass of a window.