2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Patrizio Corda

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

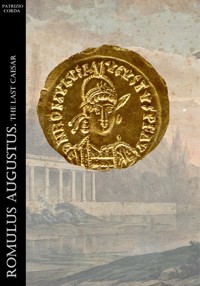

476 AD - In the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire, the last emperor of Rome, the young Romulus Augustus, is deposed by Odoacer and relegated to captivity in a villa in Campania.

As he sees his world dissolve, Romulus vows to himself to get his revenge. In the dark corridors of his prison, Romulus will find an unexpected help who will restore his freedom, beginning an incredible adventure to the borders of his late kingdom, in search of a way to one day return to the place where he had been lord of half of the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Romulus Augustus. The Last Caesar

Indice dei contenuti

ROMULUS AUGUSTUS. THE LAST CAESAR

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

XLVII

XLVIII

XLIX

L

LI

LII

LIII

LIV

LV

LVI

LVII

LVIII

LIX

LX

LXI

LXII

LXIII

LXIV

LXV

LXVI

LXVII

LXVIII

LXIX

LXX

LXXI

LXXII

LXXIII

LXXIV

LXXV

LXXVI

LXXVII

LXXVIII

LXXIX

LXXX

LXXXI

LXXXII

LXXXIII

LXXXIV

LXXXV

LXXXVI

LXXXVII

LXXXVIII

LXXXIX

XC

XCI

XCII

XCIII

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THANKS

Reserved literary property ©2024 Patrizio Corda

ROMULUS AUGUSTUS. THE LAST CAESAR

Patrizio Corda

To my mother

I

Acclamation

Rome, October 31, 475 AD.

Romulus turned once more and met his father's gaze, proud and reassuring behind him.

Don't be afraid.

He should not have had any, actually.

What dangers would he be in?

He strove to assume a more regal bearing as he timidly spread his arms and welcomed the acclamation of the Senate in the Curia Julia, in Rome, the center of the empire.

What was now his empire.

Anyone else, facts in hand, would not have cared in the least. His father, Flavius Orestes, was the reigning patrician, swept over all of Italy with his Romanus-Barbarian troops, and was in fact the most powerful and respected man in the entire Western Roman Empire.

The ruler appointed by the Eastern Emperor Leo, the former governor of Dalmatia Julius Nepos, had been unable to oppose the will of his father, who had pressed him with his militia and forced him to flee hastily from Ravenna to the coast from whence he had come.

This would probably have created quite a bit of friction with the more powerful Eastern court, there was no doubt about that.

But why on earth was he having such problems at the age of fourteen?

He was a little boy!

He should have simply enjoyed the moment, begun to become familiar with the disruptive feeling of power that came from the purple he wore and that seemed to him instead always either too long or too short on his longish physique.

Why instead of quivering with joy was he assailed by all those anxieties and doubts?

Romulus knew the answer.

He was so concerned because he cared.

He did not know what his father believed, but he was certainly not going to be his puppet. He really wanted to rule, and to do so to the best of his ability.

And those senators whom he saw lavishing the most disparate praise on him, he would really have wanted to engage them, to wrest them away from pursuing their own interests as impresarios and landowners that was plunging the empire into famine, and to remind them what role they played.

He would have liked to reign in concord with them and raise with new political solutions a reality that was instead in shambles.

He was a young boy, yes, but he already had a clear picture of the situation.

The people were reduced to starvation. All around Italy, with the exception of Noricum, Dalmatia (actually loyal to Julius Nepos) and part of Gaul, were barbarians who had taken by force what Rome had failed to defend with the passage of time.

Tax revenues were no longer enough. People preferred to enslave themselves to the landowners-and many of these stood there before him-rather than enlist and reverse the trend that saw imperial armies almost entirely composed of barbarian mercenaries.

So were his father's militias.

His father, too, was in part a barbarian. He had even served under Attila in his youth, in the presence of that monster who almost set the empire on fire.

Precisely for reasons of blood, Orestes had not been able to rise to the diadem. Therefore he had decided to have him elected.

A noble Roman with pure blood.

But also easy kid to maneuver.

He loved his father, but that would not be the case.

As soon as he had a chance, he would have told them in no uncertain terms. He would, as far as possible, do his best to reign wisely. He would not have been afraid to ask for advice, from him as from anyone else given his age, but he would have made the decisions in the end.

That purple so uncomfortable and that seemed to clash with the verdancy of his years seemed to have already catapulted him into a different reality, where games and carefreeness were now making way for a sense of duty and responsibility to lift up a glorious empire now reduced to the shadow of what it had been.

The names it bore, moreover, should have made it clear long beforehand what it was intended for.

As the senators' shouts and invocations, admittedly not as charged with enthusiasm as he had hoped for waned, Romulus sat down with feigned calm and scrutinized them more closely.

He felt his father's heavy gaze behind him.

In front of him, eyes of people who had spent their lives looking after their own gain, skilled political minds, opportunistic and devoted to nothing but their own constant enrichment.

In that building where the history of Rome had been made, he felt the moment that marked his rise to power coming inescapably.

Yet he could not banish the sinister feeling that he had walked into a trap.

II

The last refuge

Diocletian's Palace, December 475 AD.

Julius Nepos instructed everyone to leave him alone.

Secretaries and servants silently walked away, leaving behind only the imperceptible rustle of their robes.

Julius stood contemplating that marvelous view from the palace in Split to the nearby islands, washed by the waters of the Adriatic that seemed to mingle with the honey-colored afternoon sky. The sea was as flat as a table.

Who knows if he would one day see boats with effigies of the Orient lapping those shores.

Yes, because his only hope of seeing his name associated with the empire again was that Constantinople would come to his aid.

After all, it was from the Bosphorus that his appointment had come. Formally, he was still the august. A fugitive augustus, technically waiting to gather arms to wipe out the usurpers, commanded by the man to whom he himself had entrusted the surviving Roman armies.

Roman, as with his nomination, only on a formal level.

Orestes was a barbarian in charge of other barbarians.

There was no longer even a military organization worthy of the name: at most, each squadron was traceable to a tribe, their officer nothing more than a clan chief.

What he found difficult to call soldiers of Rome were people who did not even share a common language.

Yet despite this, he had failed to offer even a hint of resistance.

It was certain that Orestes had secretly arranged with the Curia.

The Senate of Rome did not like to be ousted from decisions, although when the need arose it always stuck its head in the sand.

An august appointed by the Eastern Empire had been a challenge to that noble assembly, an unforgivable affront to its history and power.

A power, once again, only formal.

So much so that it had only taken a mass of mercenaries to convince them to appoint by unanimous vote Orestes' son Romulus, whom they already called "Augustulus" because of his tender age.

Poor boy, he did not know what beasts he had gone into the den of.

In essence, the whole Western Empire was a set of useless formalities. His army, the usefulness of the Senate, the lands lost to the barbarians that they nevertheless persisted in reputing as kindly granted to them. His crown.

All fake, all only on paper.

And like paper itself, easy to destroy, turn to ashes and disappear, doomed to oblivion.

Well had Diocletian, the Caesar in whose palace he had taken up residence, abdicated to live the last years of his existence in peace!

He, on the other hand, would have to spend the rest of his life, assuming Orestes had not come looking for him, brooding, filling his head with "what ifs" and "buts," fantasizing about scenarios favorable to him that would never come true.

He would gird a paper tiara until the end of his days.

The empire would dissolve shortly thereafter.

He could feel it.

He had accepted the purple with all good intentions, but once he arrived in Italy he realized that the stories that had come to his prosperous Dalmatia were not even close to the tremendous reality of the facts.

The economy was collapsing. Bureaucracy and civic works seemed to have stopped at the time of Honorius, decades earlier. Corruption was rampant, and taxes were unsustainable. Not infrequently those who had businesses found themselves forced to sell their children to pay debts incurred with powerful or even outright torturers.

The citizens all seemed to be beggars, the children covered in dirt, lousy and scarred with boils and eczema.

Dirt and garbage were everywhere.

The grandiose monuments of the past had become haunts of stray dogs or worse, orinals. Under those fantastic porticoes throngs of beggars and beggars were fighting over lumps of stale bread, waiting for yet another free handout of provisions.

The Church, strong in these duties, had become most powerful, and priests and deacons with their words easily subjugated the almost completely illiterate people, instilling them to resignation as they awaited God's judgment and the end of time.

People believed a monk more than the august.

They went to be slaves of the landowners, giving up putting down the plow to take up arms and conquer new lands that perhaps could have gone right to them.

And the rich meanwhile became wealthier and wealthier, while poverty gradually spread to a larger and larger portion of the population.

The Romans hated the barbarians, but they had neither the courage nor the will to defend themselves from them, to take back what was theirs.

He had inherited empty imperial coffers, and what little funds he had been able to manage he had had to devote to foraging troops-the very troops that Orestes later turned against him.

And so, no matter how hard he tried to deny the evidence to the last and hope for the patrician's good faith, he found him at the gates of Ravenna.

He had had to run away.

He hoped to organize a redemption, but he honestly did not know where to start.

He did not honestly trust his officers either, now that his position had weakened.

Dalmatia was a rich and loyal region, well defended by a large fleet, whose people were happy and seemingly uninterested in the misfortunes of that Italy so near but at the same time so far away.

His subjects would never even consider the idea of going to war and giving up their pleasures to redeem a desolate, unproductive heath populated by people now reduced to misery but who had not lost the inherited glory of a glorious past as distant as it was irretrievable.

Damn, he had even married a granddaughter of Leo as well!

Yet it had not served to secure him more support.

Then again, there had been changes in the East as well.

Leo had died, and so had his grandson Leo II. Zeno had ascended to power, but then General Basiliscus had usurped the throne.

All that was left to do was to await the next developments, and to trust in a confirmation of his appointment and a possible helping hand.

Alone, it would have been impossible for him.

That incessant reasoning made him lose track of time.

He suddenly realized that evening, as is often the case in winter, had suddenly fallen.

A purplish veil was falling over the islands and the sea.

All that remained were dim orange splashes on the horizon, legacies of the dying sun.

Julius continued to caress the sea with his gaze, then clenched his fists vehemently as he bowed his head.

It was beginning to get cold.

He told himself that he would have to start living with that feeling, which would probably accompany him to the end of his existence.

The feeling of being completely powerless.

III

The promise

Noricum, January 476 AD.

Odoacer remained stooped, his head almost between his knees as he ran his hands over his face. He felt his beard, red and bristly from recent shaving sting his palms. Then he crinkled his tired, flushed eyes and lifted his back, sitting on the rough wooden stool in the center of his tent draped with skins.

He motioned the secretary to let in those who had requested an audience.

A group of a couple of soldiers appeared before him.

He recognized among their faces a motley mix of races, including Heruls, Scyri and Rugians and others of lesser importance.

An elderly but still sturdy and daring soldier, far older than himself, came forward. His face and body were covered with tattoos and scars. Wearing, not a garment that would suggest he was a Roman soldier.

"Prince Odoacer," exclaimed the one.

It began badly. He hated to be called a prince, although indeed he was, as the son of the king of the Heruls, Edecon.

He had always asked to be called a general, or at the limit how by his soldiers. Roman titles, because Roman was that army, at least in theory.

But it had been a while since the soldiers, driven by an eagerness to be rewarded for their services after Orestes' promises, had been trying to appeal to the fact that, as they were all born beyond the imperial borders, there might be some solidarity among them.

"Prince," repeated the soldier stubbornly, "I guess you know why we are here stealing your precious time."

Odoacer did not move an eyelash. He tried to keep a bearing that aided by his robust and still athletic physique could be as authoritative as possible. He darted his emerald green eyes, staring into the eyes of everyone present.

Rome's soldiers, but also his own. That's why he felt so uncomfortable when that matter was brought up.

"I guess so," he replied dryly.

The man did not seem intimidated by his toughness.

"About the arrangements with Patrician Orestes, we are to ask if you have any good news about the hospitalitas."

He knew it! Here they were coming back to pull him in.

But in the end they were right. Barely paid with the last imperial funds, those mercenaries who referred to him and trusted him had been told by Orestes that as compensation for their loyalty they would receive a third of the lands of Italy.

The just reward for helping him overthrow Julius Nepos.

He felt an uncomfortable burning sensation permeate his stomach.

Yes, he had news to that effect.

But they were not good.

Orestes had solids minted in Rome, Milan, Ravenna and Arles with the face of his young son, Romulus, whom he had recently installed in power.

He was convinced that he could dispose of Italy and its armies as he wished.

Well, it wasn't quite like that. And if a barbarian like him had accomplished it, he really didn't understand how the patrician of the Romans could have believed in mocking his troops so shamelessly.

Yes, he had written to Orestes.

He had asked him, on behalf of the Army of Italy, to match what had been promised as soon as possible. Not that he was interested in having additional possessions. His father had been a great king, who had fought with Attila, and had left his sons a multitude of property and wealth.

But those soldiers who knew how to do nothing else with their lives but fight for the highest bidder deserved recognition. A prospect of life and stability.

And if they had not had it, further problems would have arisen.

How could the idiot not understand that?

Had he brought those tribes to Italy to serve him and then thought he could send them back to the forests, without a penny or a semblance of loot and stay nice and quiet in Ravenna?

Evidently, he had overestimated the man.

Since he had set foot in imperial lands he had learned the typically Roman art of being mellifluous and of not compromising too much by taking one side over another. In fact, at Orestes' rejection-cold and disdainful-he had tried to restrain himself so as not to antagonize him.

But morally, he felt he could not exempt himself from standing with his men. Blood was blood.

And they were trying to leverage that to pull him from theirs.

The balance was really precarious, and he was in the middle, between the patrician and his men, between his career and his identity.

He cleared his throat slightly.

Then he assumed a testy expression, as hard as his facial features, stiffening his mighty jaw.

"Well, soldiers, do you think that missives can reach in this way, in the blink of an eye all the way to Ravenna? You know very well where we are. It will still take time for the reply of Patrician Orestes to reach me."

"But prince, we-"

"I am your general," he scanned in a deep voice.

The soldier instantly stiffened.

"I have already told you that I will plead your case to Orestes. What more do you want? As soon as I hear from you, you will of course be the first to know. And now go."

The men gave a quick military salute and exited the tent.

Left alone, Odoacer sighed and dropped into his chair.

He had better prepare himself for the irreparable.

IV

Hopes

Rome, March 476 AD.

He had insisted despite the remonstrances of his mother Flavia Serena, who kept clinging to his arm even though they were safe in that wagon escorted by undercover guards.

People would have thought it was the passing of some rich landowner, at most some senator.

Romulus had been adamant in his decision.

He wanted to walk around Rome. He wanted to see his city.

He had a terrible need to understand.

His first months had been very hard. Ministers seemed to pity him and not inform him of anything by virtue of his age, believing that his input and opinion were immature and irrelevant.

He had pounded his fists on the walls, barely stifled his cries.

He walked around his apartments like a fury, feeling mocked.

He spent hours in the mirror looking at himself.

Slender, tall and good-looking with the delicate features and fine nose of nobles. Hair between blond and brown, medium length and wavy. Already he was beginning to like purple.

But then, if he had all the qualifications, rank and otherwise, why didn't they make him a participant? Why were they treating him like a child?

It was absurd. He should have been the one to decide who to surround himself with, and not those obscure dignitaries!

He had already had a rather harsh confrontation with his father when his father had decided to convene a session in the Senate and he, with the unscrupulousness of adolescence, had pointed out to him that it was up to the augustus, that is, him, to convene the assembly.

The father had squared him frostily, but preferred to gloss over.

His mother, she, on the other hand, understood his frustration.

He could not accept being a puppet in the hands of people accustomed to changing flags in order to save their seats.

He knew that his father had some trouble with the army, but he had not paid much attention to it. He was interested in reviving the economy.

But all they had told him, between bows and rhetorical formulas full of piousness, was that at the moment the coffers were languishing, and that all that remained was to appeal to divine clemency for the misfortunes of their times.

Even Pope Hilary had seemed shy to him during the conversation they had held, as if he felt diminished to be conversing with a young boy, however polite and much more educated than average.

His mother gently stroked him, guessing from the sadness in her gaze what he was thinking about.

"Thank you," Romulus told her with sincere affection, smiling and kissing her on the cheek.

No, he wanted to be august. Not just be one formally.

He had demanded, going so far as to shout and throw what came within his reach, to go out into the city. And in the face of his mother's pleas, concerned for his safety, he had decided to accept the compromise of the carriage.

What a sad spectacle had presented itself to him!

With the eyes of the teenage scion he had never paid attention to it, but now that civic sense was burning in him, he saw.

And he felt like crying.

The stench of Rome was unbearable, a mixture of sewage struggling to be disposed of by cloisters and something else undefined, including steaming cauldrons, rotting animal carcasses, urine and rotten food abandoned on the streets.

Peeling back the curtains he had seen plague-ridden children, their hair greasy and full of lice. Their bellies swollen and ribs protruding, their limbs skeletal, their clothes soggy and patched.

Most store windows were barred or bore shattered glass. It was common knowledge that the rampages of circus fans did not spare even their fellow citizens.

Glorious temples such as that of Jupiter Capitolinus, who had watched over the rise of Rome, were closed but still accessible to the wretched who sought shelter there, or worse still to the vandals who used to do their business there.

Even modesty was now forgotten.

Nero's Baths had seemed to him to be in a very bad state.

Everywhere were potholes, and more than once the wagon had risked losing a wheel. He had seen throngs of psalmodizing priests exhorting passersby to surrender to the call of Christ, renouncing the fight against earthly misfortunes.

And people would crowd around them and then go and find some Jews to beat up in the name of Jesus.

He crossed his gaze with his mother's mournful one.

That he did not care, because in that debacle made up of total poverty, lack of resources, and total distrust of the future he had still found something to draw inspiration from.

In that full-day visit, with one of the typical leaps of youth he had indulged in the magnificence of the monuments erected and dedicated to the greats of the past.

The Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, the Aurelian Column.

Then again, the Pantheon, Hadrian's Mausoleum and the arches of Constantine and Claudius.

But out of all those magnificent treasures of the past, what had made him fall into a state of total admiration was the Column of Marcus Aurelius.

Struck as if by magic by a ray of sunshine on that rainy day, the column in the middle of the Campus Martius, with its highly detailed bas-reliefs and incredible height, had seemed to him as if it could speak to him.

The august philosopher. He had read and reread it, studied it and guarded it jealously in his heart. If he had to choose an emperor for inspiration, it would surely have been him.

He regretted not being able to get out of the wagon to stand at the feet of that marvel, gaze at it closely as he had been able to do freely until a few months ago. And why not, maybe ask that enlightened man for advice on what to do for his people, on how to make himself useful despite his green age.

On how to raise up that city that was unraveling but that he loved madly, and with it the empire that had been and that it seemed could be no more.

Before leaving, he had seen a small group of mercenary barbarians loitering with their noses up in that authentic open-air museum, almost intimidated.

He thought that Marcus Aurelius had spent his life planning campaigns to defeat and keep those people away from the imperial borders.

Instead, now the barbarians were among them, perhaps even more numerous, strong and eager to make them all that magnificence to which it seemed untrue to them to admire.

The Romans, on the other hand, were old, flabby, greedy and lazy, devoted only to lust and petty amusements such as racing, dice, and bad women. Totally disinterested in public affairs.

It seemed impossible. But he would still try.

Those reminders of Rome's past greatness made him believe that anything could be achievable. If they had extended the empire's influence over the whole known world from nothing, so could he, with a little luck and the restraint that Marcus Aurelius had suggested to him through his sublime writings.

Rome would rise again and a new era would begin.

It would have been exhausting, but he had age and the desire to grow along with the capital of the empire he now held.

He closed his eyes for a moment and clenched the fists he held on his knees. Then he peeled back the curtain again and looked back.

The column of Marcus Aurelius was now far away.

But he promised himself that he would return that evening to ask his advice, diving back into reading the legacies of the immense man whose legacy he hoped one day to live up to.

V

Retaliation

Isauria, June 476 AD.

Zeno continued up the scrub-covered hill, unconcerned about his troops clinging a little further downstream.

He wanted to be alone for a while.

Sifting, without the constant meddling of his wife Ariadne, how many real chances he had of making the Eastern Empire his own again. He scanned the rangy horizon.

At that point, he really had a lot.

Primarily, he had on his side the fact that although hunted, he had managed to escape with almost all of the incalculable imperial treasure of Constantinople. Wagons and carts filled with gold solids, jewelry, gems and precious objects. Of the wealth of the East, his persecutors had found very little.

Second, the population's hatred for the Isaurians-and thus for him-had waned, as they had found themselves with a government made up of usurpers and, moreover, with the imperial coffers considerably impoverished.

There were all the elements for him to return to the Bosphorus, and triumphant to boot, shoving in the face of enemies and detractors the fact that as a fugitive he would return as a savior.

Yes, reasoning without Ariadne was much easier.

His wife looked more and more like her mother Verina, who had first supported him and then decided to overthrow him, drawing from her the general Illo and getting her brother Basiliscus elected.

Of course women, when they tasted power, knew how to be more dangerous, devious and deadly than one might have thought.

He would not let his wife take more space than he had already given her.

Rather, he would unceremoniously dispose of it.

Purple, and the dynamics that led an individual to it, were not things that pertained to women.

With his thoughts, he then went on to reflect on a particular event that had restored his confidence to become the august again.

Should he have believed the vision he had?

A few days earlier, in the unbearable heat of his tent, St. Thecla of Iconium, the martyr disciple of the apostle Paul, had appeared to him in his sleep. This one had urged him to rid himself of all reluctance, and to move toward Constantinople to take back what was rightfully his.

He had guarded the memory of that apparition jealously, without confiding it to anyone. He sat down on a large flat stone and began to fiddle with the earth, picking it up and then letting it slowly fall back to the ground from his half-clenched fist.

Like the sands of an hourglass marking time.

That time that again seemed to have to be his.

He would not be merciful this time.

Many had betrayed.

From General Strabo, to that Patrician whom Verina had supported to her detriment and who had dared to massacre all the Isaurians left in Constantinople after his escape.

He could never forgive such an affront, nor could his militia, of his own nationality.

Back in his homeland, he had taken to recruiting those tough people accustomed to mountain life by appealing to the sense of belonging and wounded pride of an ethnic group whose most prestigious exponent had been unjustly outraged.

Let Basiliscus be ready, for he would not have an easy time with his armies.

Driven to positivity by the objective picture of things, he took to making good resolutions. Once he returned to the throne he would put his finances back in order, make some changes in the army, and enact some provisions that could strengthen the untouchability of his status.

Moreover, he himself had proved how ephemeral even the role of an august could be. The same fate had befallen Julius Nepos, the colleague whom Leo, his predecessor, had appointed to lead the wretched West.

He had learned that the latter had been deposed, and that in his place a little boy, son of the patrician of the West, Flavius Orestes, had been elevated to the purple.

It was his understanding that he was fourteen years old or so.

Child.

So was his son Leo II, who died very young, at the age of only seven of a lightning-quick illness to the point that he did not even allow thought of a cure.

She recalled with sorrow the little body of her son wrapped in purple, his round face motionless in death.

He would have retaken the East in his name as well.

VI

King

Noricum, August 23, 476 AD.

It had finally happened.

There he was, on that stage pulled up as best he could with thousands of mercenaries in front of him, a cauldron of races and tribes like he had never seen. And the tension was through the roof. Eventually Odoacer had to confess to his men that Orestes had changed his mind, and he had no intention of granting them any land. In fact, he had even ordered them to winter outside Italy. The empire had no solid in its coffers.

The camp was then shaken like an earthquake as word spread.

In order to appease the wrath of the men, who had begun to raze their own fortress and were agreeing to cross Italy by raiding, Odoacer was determined to show himself, to make one last attempt to stop them, to induce them to a reasonableness he knew they would never show.

He would even pay out of his own pocket to restrain them.

But this, and he knew it well, would have meant making enemies of them, proving that he once again preferred to bow his head before Rome, just when Rome was now defenseless while never before had the peoples of the North been so united and outnumbered.

Odoacer adjusted his belt buckle in the shape of a dragon's head, and planted himself wide-legged in front of the crowd.

"Soldiers!"

Tents continued to be thrown down before his eyes, and several fires had already been set.

He noticed that many men had their swords drawn and were staring at him.

"Soldiers!" he then shouted over the incessant noise.

His naturally squeaky voice, ideal for his leadership role, instantly attracted everyone's attention.

"Are you then on the side of the Romans, prince of the Heruls?" burst out an indistinct voice, followed by roars of assent.

"We are tired of being treated like animals! The Romans stay warm, in the comfort of their homes, and they owe it only to us! And as a reward, what does Orestes do? He deludes us, sends us to die for him and then forces us to go back to sleep under the trees, to make our families suffer hunger and frost!"

The speaker was the same veteran who not long before he remembered presenting himself pleadingly in his tent.

Indistinct shouts followed, then actual insults that made the blood boil in Odoacer's veins.

He had heard the word servant, and then again coward.

And that Odin had called him to himself at that moment, if he was ever even for an instant a coward or a servant of the Romans.

He felt the need to vent.

"Now then, what do you demand of me, men?" he shouted back. He must have seemed truly exasperated, because the soldiers' expressions immediately seemed different to him. How astonished.

"I did my best to ensure that you were granted what was promised. Flavius Orestes, however, did not want to fulfill the covenants. But I still remain a faithful servant of Rome!"

"Servant?" a voice mocked him.

"So Orestes is bullshitting us and you're still keeping quiet? Your father Edecon would turn over in his grave if he knew!"

That reference to his father, who had once threatened the empire alongside Attila, stirred him to the core.

He, on the other hand, his prince son, had ended up serving Rome. But he did so for the love of civilization, for how his life had changed since he had set foot in the Forum. A new reality, governed by laws far removed from the barbaric feuds that washed only in blood. There he had known the courts, and then regularized commerce, discovered previously unknown trades, learned the rules of behaving in various contexts.

He had learned to read and write, and to appreciate the art and beauty that seemed to shine in every corner of that city.

He could never return to the barbarism of his youth.

That is why he suddenly felt close to his men.

He understood that their feelings, their frustrations would also be his if he found himself in their situation.

They were their brothers. He had to help them.

It was not Rome that was a traitor to their loyalty.

It had been Orestes.

He had to get clarity in his mind: the man was treacherous and incompetent, and he had to be eliminated. His men deserved to have their agreements fulfilled. That their families would have a better life. This did not necessarily mean that Rome, beautiful Rome, would have to be razed to the ground....

"Be worthy of your lineage, prince! Fulfill your destiny!"

"Lead us against those who want your people hungry and homeless!"

"Son of Edecon, be worthy of your father!"

He would have liked to render all those mouths mute, but their call was becoming more and more irresistible.

Did he wish to be the king of those people?

What would it have led to?

"Long live King Odoacer!"

That scream almost made him lose his balance.

He did not have time to raise his arms to invite everyone to calm and dialogue, and dozens suddenly swooped onto the stage, rattling the wooden boards.

They took to calling him king, liberator, and within moments he found himself on their arms, hoisted up and launched into the air despite himself.

He had the feeling that someone else had decided for him.

Perhaps, from Valhalla it was his father's spirit that had changed the course of events.

Now he was king.

Now it was going to be war.

VII

The shield of the empire

Pannonia, August 26, 476 AD.

Theodoric let out a shout, beat his fists with formidable power on the desk, and raised his arms to the sky in victory.

"What makes you rejoice so much, my lord?" asked Roxanne, the consort of the king of the Ostrogoths, in a persuasive voice, slipping sensuously behind him and encircling him from behind.

Theodoric let his head go back, abandoning it to the softness of her chest.

He had just received great news.

"This letter," he said in an excited voice, waving the parchment he held in his hand, "this letter will mark the ultimate stability of our people!"

Roxanne tried to conceal her interest, smiling and pretending not to understand. But Theodoric would never be charmed by those dissimulations of hers.

He loved her, and would never give up the ardor of their carnal unions, but he knew that Roxanne had a refined political mind.

Too refined not to be able to read between the lines and aspire to influence decisions at court with the cards at her disposal.

However, those matters would be up to him alone.

That he understood it right away. He was in charge.

"In these lines, the august Zeno has complimented me on having kept off the hordes of Slavs who thronged our borders from the East. He welcomes my experience in Constantinople and the fact that I received an education in keeping with what befits a nobleman of the empire. He applauds my youth and my moderation in reigning."

"E...?"

Roxanne leaned back slightly, making her abundant breasts dance in front of her man and covering his face with her long auburn hair.

"And so, since you really want to know everything," he reacted, getting up suddenly and grabbing her forcefully by the waist, "he proposed an alliance to me."

Roxanne suddenly changed her gaze, becoming serious and doubtful.

"You know well how notorious the court of Constantinople is for the murky plots that arise and develop there, Theodoric. Zeno himself was deposed by his mother-in-law, only to take back the throne by force. Treachery is the order of the day in that city."

"The august one has sworn on his honor," he replied, reciprocating with an icy look and squeezing her even tighter. He was certainly not taking advice from her.

At that point, Roxanne melted into a warm smile and embraced him with transport.

"I just want you to be safe. You are our king."

"From today, with the appointment of Augustus Zeno, I am also an ally of the Eastern Empire, my dear. This means that I, commanding the army of the Ostrogoths, will defend the borders of the empire of Constantinople."

"I would not want that man to do that while conferring on you.

a great honor, with the purpose of effortlessly keeping the barbarians away and then annexing the lands we conquered with the spilled blood of our ancestors."

He was damn smart. You had to give him credit for that.

"I have also thought about this. I would be a fool if I ruled out a priori that Zeno also screened this possibility in his favor. But you know what I tell you, my queen? No one will be able to take away what we have taken from each other after a thousand battles. Not under my reign. This alliance will enrich our people and enable them to start important trade networks. We must look beyond, as our illustrious predecessors did not. It is time for the Ostrogoths to stop being merely fighters feared throughout the empire, and to draw inspiration from greater ideas to live in prosperity. After what I saw in Constantinople, I would be a coward not to aspire to give as much to my people."

An enlightened ruler, that's what he wanted to be.

With Rome now dying, it was the East that was the real force to look to forge an alliance.

And there was no need to worry about any betrayal of signed agreements. Not now.

Zeno was no longer so strong, even though he had returned to the throne.