2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

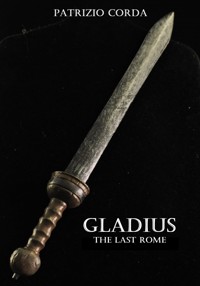

- Herausgeber: Patrizio Corda

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

260 AD. - After a long and luminous military career, which led him from a simple recruit to becoming governor of Germania Inferior, Marcus Cassianus Latinus Postumus finds himself at a crossroads. Fraternally bound to the legionnaires but bound to obey the orders of the august Gallienus and his despotic son Saloninus, he is forced to make a choice from which he has long fled: listen to his heart and dare

leveraging the support of the troops, or continue to live as a servant.

His decision will radically change the Roman empire of the third century. In an era marked by barbarian invasions, infighting, and especially secessionist uprisings, Postumus will emerge imposing himself as the best alternative to the legitimate emperor, giving rise to a kingdom that will hold Rome in check for years.

And which, like the latter, will experience harsh battles, betrayals, and fatal conspiracies.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Postumus. Imperator Galliae

Indice dei contenuti

POSTUMUS. IMPERATOR GALLIAE

Patrizio Corda

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

XLVII

XLVIII

XLIX

L

LI

LII

LIII

LIV

LV

LVI

LVII

LVIII

LIX

LX

LXI

LXII

LXIII

LXIV

LXV

LXVI

LXVII

LXVIII

LXIX

LXX

LXXI

LXXII

LXXIII

LXXIV

LXXV

LXXVI

LXXVII

LXXVIII

LXXIX

LXXX

LXXXI

LXXXII

LXXXIII

LXXXIV

LXXXV

LXXXVI

LXXXVII

LXXXVIII

LXXXIX

XC

XCI

XCII

XCIII

XCIV

XCV

XCVI

XCVII

XCVIII

XCIX

C

CI

CII

CIII

CIV

CV

CVI

CVII

CVIII

CIX

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THANKS

Literary property reserved ©2024 Patrizio Corda

POSTUMUS. IMPERATOR GALLIAE

Patrizio Corda

To my family and readers

I

The fate of the humble

Surroundings of Lutetia, April 232 AD.

"Make way for Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander Augustus, Caesar of the Romans!"

At that cry, the camp suddenly seemed to come alive after days of languid apathy on that bare plain circumscribed by fog, whose green lawn had been turned into a muddy mush by the rains but also by the constant trampling of legionnaires bored and frustrated by immobility. Contrary to the instructions of Emperor Alexander Severus' bodyguards, who still hid from everyone thanks to the heavy purple drapes that wrapped his chariot, dozens and dozens of soldiers abandoned their tents to witness the happy event. It happened more and more rarely that a Caesar dignified the troops with his presence.

And yes, that legion, the XXX Ulpia Victrix, had sprung from the very intuition of an emperor. Perhaps, the augustus who of all had most empathized with the valiant men who had made Rome so great and powerful. Marcus Ulpius Trajan.

For that reason, too, Postumus had chosen to enlist in that particular corps. Moved by the desire to serve the empire in which he lived, he had finally resolved to offer himself as a volunteer recruit in the hope of filling his future life with adventures, victories and honors. But also of unrepeatable moments like that.

As Alexander Severus' chariot advanced, its wheels sinking creakily into the mud, more and more legionnaires crowded along its sides. Some already fully clothed, others still busy adjusting their lorica and worried about their less-than-polished weapons.

Their anxieties became those of Postumus, who was a victim of typical teenage eagerness and had not cared much for his appearance.

Paling, he took to groping in anguish in desperate search of his sword. He realized, then, that he did not even have his helmet.

He looked behind him, where his tent with its effects was.

He could not show himself in that state to the august!

What would have happened if he had leaned out and noticed his lack of care and discipline?

The mere idea of a public rebuke and its possible consequences paralyzed him. He made to back away, but just then Alexander Severus' chariot veered sharply to avoid a deep ditch.

And with it also changed course all the escort men, many of them praetorians who were very loyal to the august and who had already caused a number of discontents in the camp by virtue of the privileges they enjoyed. But Postumus, barely seventeen years old, took no interest whatsoever in the matter. His mind was totally engaged in devising a way not to be seen in that ridiculous state. And that was his biggest mistake.

He did not notice the theory of praetorians lining the left side of the chariot and how close he was to them.

Far too close, to the point of being a real obstacle for them.

"What the fuck are you doing, little boy? Are you obstructing the passage of your emperor?"

Hearing those words and feeling a chill down his spine, Postumus turned around with his eyes wide open. He was just in time to see two flaming, rabid globes under his helmet and a shapeless mass moving toward him. The impact was dull, devastating, and so painful that he could not even scream.

He simply fell on his back, sinking into a pool of dirty, foul-smelling water with his face catching fire.

He instinctively brought his hands to his face, and for a few moments he neither saw nor felt anything. Those moments of suffering also made him forget about the august and the vehicle that carried him.

He felt the bitter taste of his own blood in his mouth, and something warm dripping profusely from his nose. He touched it.

And it looked nothing like he remembered it. Instead he was an amorphous, soft mass, propagating excruciating twinges throughout his body at the slightest touch. He wept tears of pain, but also tears of shame realizing the foolishness he had made.

He then got up groaning, trying to see with his moist eyes how many had noticed the humiliation he had suffered.

Before he could realize this, however, he noticed that the chariot had already moved quite a distance away. In a flash, Alexander Severus had left them behind. And without even showing himself for a second.

With his legs shaking, Postumus moved a few steps rubbing his face. He looked at his palms: they were smeared with congealed blood. But the bleeding had not yet stopped.

His entire boyish face, now marred, was sticky and seething from the liquid that had flooded it.

What had he done wrong to deserve this?

Was not moving too fast reason enough to be beaten so fiercely?

Would the emperor have known about him?

Alone and distraught, Postumus had no better idea than to retreat to hide himself as much as possible from the criticism and mockery of his comrades.

But before he could escape, a large calloused hand rested on his shoulder. Fearing the worst, he slowly turned around.

In front of him he found a middle-aged man with a yellowed but groomed beard and two green eyes filled with understanding.

On that sun-baked and wrinkle-scarred face, Postumus discerned no threat. He tried to remember the name of the man who had stopped him. The man was a veteran of the legion.

And he had always felt others approached him with deference, by virtue of his age but also his tremendous experience.

Aquilius. Here is his name.

"Stop for a moment, boy," these imposed on him, speaking to him in a voice so hoarse that it reminded him of the scraping of a shovel on parched ground in the summer months.

Embarrassed, Postumus obeyed and did not move. But he bowed his head, in a painful attempt to hide his swollen face from him.

In a fit of paternal compassion, Aquilius shook his head.

"What are you, son?"

"I..." murmured Postumus "...I am a Batavo."

He bit his lip, damning himself for the way he had spoken. He should never have referred to his roots in such a resigned way.

He was an imperial citizen in his own right, after all.

He was certainly not a criminal, or an illegal immigrant.

But Aquilius did not care for his tone. He merely sighed.

"You don't have to be angry about what happened to you, although I understand that at your age one can be enraged by much less. You have to understand that unfortunately this is the world you have decided to live in. There are things that are detestable but that we have to put up with every day. And the sooner you understand that, learning to stand your ground and swallow the bitter pillows, the better you will live in the future."

Instinctively, the veteran turned toward the imperial chariot, which was now a tiny silhouette on the horizon. It seemed that the august one wanted to stay as far away from them as possible.

With the wise disinterest of one who had now seen everything, Aquilius shrugged his shoulders. Then he went back to staring at him.

"What is your name, young man?"

"Postumus," he replied, now more at ease. "Marcus Cassianus Latinus Postumus." He said it with newfound conviction.

"Good. Then, Postumus, reflect on my words. And treasure them. For rest assured, this is only the beginning."

At that point Aquilius gave him a resounding pat, which caused him to bend in two, and finally left him alone. Meanwhile, all the legionnaires had returned muttering to their days. As if no one had witnessed what had happened to them just moments before.

He was left alone, Postumus. With a broken nose, bloodied hands, and mud on his ankles. Still shocked by that unexpected misfortune and momentarily away from the pain, he felt more doubtful than ever. He had chosen that life, though hard and complicated, to snatch his humble family from misery. But lo and behold, this no longer seemed to be the right solution for him.

On the contrary, it seemed to him a condemnation. That of never being able to climb the long and winding ascent to glory and wealth.

Remaining relegated to his feet. Perhaps, forever.

II

Second thoughts

Surroundings of Lutetia, April 232 AD.

A few days had passed, but the pain showed no sign of abating. Every movement of his face, even the simplest, cost him immense fatigue. Not to mention eating: with every bite, he kept feeling as if his teeth were about to give way and fall out at any moment.

Rising wearily from his bed made of straw, his limbs heavy and numb, Postumus wondered whether to look at his reflection once more for improvement. He had done so obsessively since the day that praetorian had brutally struck him by smashing his nose. Resorting to the only object in which he could mirror himself, a crude and sharp piece of now-opaque glass, he had contemplated the effects of that tremendous punch countless times. And every single time he had been disgusted by his new features, by that swollen, purplish face that resembled the most grotesque of masks.

He had never been comely, Postumus.

His square features and curly, raven hair had always given him a more mature appearance. But now even his clear eyes could not have given him a glimmer of charm, with that distorted and crushed septum still making him cry out in pain. Even if someone had deigned to treat him, he would never be the same again.

That thought saddened him, confronting him with his utter helplessness. Listening to the grunts and curses of the other legionnaires as they in turn woke up, he decided to do the only reasonable thing in his condition.

Ignore those inner monologues imbued with melancholy, and face the day to the best of your ability.

He thus stepped out into the open, peeling back the felted and filthy flap of the tent that housed her. In front of him, he found a sight no less bleak than the image of his transfigured face.

The field was still reduced to a muddy, barren expanse that not even the rising sun seemed to be able to brighten.

Already a few legionnaires, in an unsuspected display of zeal, were yawning around holding their horses by the bridle.

Yet another day of training was ahead, in the absence of an enemy to face or even remotely control.

That morning, however, was to be different than usual.

In theory, he and the hundreds of his comrades would not have to passively repeat the usual maneuvers with the sole intent of keeping themselves ready. On the contrary, their incessant practice would have been a matter of judgment for someone extremely important.

Alexander Severus himself.

From the day of his arrival, the young augustus who had come from the East had hidden himself from their sight, preferring to stay in his giant tent and rest after the long journey he had undertaken.

Now, however, he seemed to have finally decided to descend among them common mortals. The emperor would ascertain the condition of the legion and its military prowess, and then decide whether to use them against the barbarian populations that had been raiding along the Northern borders for months.

Regaining hope as he dragged himself through the mud, Postumus convinced himself that by showing extreme preparedness he could redeem himself in the eyes of all after the humiliation he had suffered. Clenching his fists and checking that his lorica was tight and shiny, he murmured between his teeth a few confused words of encouragement.

He then walked toward a group of older soldiers gathered around the remains of a now extinguished fire. He saw them jostling, shaking their heads and huffing noisily.

One of them, a man over 50 now weighed down and hairless, turned toward him. And noticing his hopeful expression, he gave him a sympathetic smile.

"I see you're pulled together, little boy," he said, motioning him closer. "Well, you can relax. Because there will be no demonstration today."

Postumus frowned and looked at him puzzled.

"What do you mean? The emperor said he would attend the drills!" he blurted out, spreading his arms wide. "We even set up the stage..." he then continued, pointing to the crude wooden structure a few dozen steps away from them.

But the veteran shook his head, more disinterested than disappointed.

"I know. But the august one will not leave his tent even today. Before dawn, he sent a messenger to spread the news that he is not in the mood to face such an undertaking. The harsh weather and lack of sunshine darken him, and he has lost any desire to devote himself to us. This is it, son. Get over it."

Now oblivious to what they were supposed to be doing, the other legionnaires abandoned the pile of incinerated logs and moved toward their respective tents. Gone was the long-planned day, they would return to their usual daily activities without any particular recriminations.

Posthumously, however, he was not able to accept that change of plans so easily. He had hoped to stand out that day before the emperor. He had imagined, perhaps sinning in naiveté, that he would capture his attention and thus regain the respect he had lost after getting battered without fighting back.

That opportunity, however, had been cowardly taken away from him.

Suddenly, the camp went back to being for him what it had always been. A sad place where nothing new or exciting was happening. The theater of a life studded with hardships, deprivations and disappointments to be endured without being able to complain about it.

In silence, Postumus took off his helmet and held it in his hands.

He observed it, as well as the lorica he had long polished.

All in vain. It had all been for nothing.

He found that beautiful, shining, finely forged metal clashed terribly with the mud, fog, and stench of excrement in which he was immersed. But worst of all, it was that he, of all people, had chosen to be there. And for the first time since he had enlisted, he wondered if it had really been worth it.

III

A valuable lesson

Surroundings of Lutetia, April 232 AD.

Fog swallowed the chariot, blurring its outlines and muffling the squeaking of its wheels as it left the field. Like a useless and forgotten collection of statues, relegated to a residence that its master no longer visits, the legionnaires stood motionless and watched as it vanished.

So profound was their silence, permeated with confusion and discouragement, that Postumus thought the mist had penetrated all the way into their hearts, dulling their judgment and taking away their speech. Only five days had passed since the Augustus' arrival, and already he was leaving.

Without ever having shown himself in public or addressed a word of esteem or encouragement to them. He would leave that bare valley just as he had arrived there. In silence, but at the same time showing off an unjustifiable pride.

What, then, had been the point of taking on such a crossing?

Why on earth had he gone all the way to the heart of Gaul if he was not interested in conferring with those who guaranteed security in those distant lands?

How shallow and capricious must he have been, the august one, to waste so many resources and subject himself to his own mood swings?

He bit his lip. He should not have thought such things of his emperor. But too much was the disappointment, not to let go of negativity and indignation.

That time, however, Postumus was not the only one who recoiled.

Looking around, he noticed all the disappointment on the scarred, granite faces of the veterans. He saw them still scanning the fog, as if they could summon the wagon by force of will.

No matter how hard they had tried not to look scalded, it was now literally impossible to prolong that sham.

Some, the most fiery, even growled insults toward Alexander Severus. Postumus was shocked by the epithets with which they apostrophized him.

Bastard, ingrate, puppet, effeminate, and even cinedus. All attributes he seemed destined to inherit from his late cousin, that Heliogabalus who had caused scandal during his short and insane reign. Evidently, the legionaries had not forgotten the dastardly rule of that ambiguous emperor.

And judging by the way he was behaving, Alexander Severus did not seem to be on the right track either.

The augustus was said to be heading east, where a more concrete threat was on the horizon. That of the Sasanids, who seemed ready to wage war on Rome by contending with him for the rich Eastern provinces. Perhaps that was why Alexander had left them so soon?

Or had he really been so disgusted with the place where they lived that he longed to leave it as soon as possible?

Hard to say. How, on the other hand, to guess the thoughts of one who had not even deigned to show himself in his brief stay?

The sadness of the legionnaires moved Postumus. Many of them were old and exhausted, burdened by years of toil and wounds that had never healed. In the morning, some were even struggling to cover a few miles of march. Probably they had trusted in the young emperor and his good heart.

They had perhaps deluded themselves that they could talk to him, plead their just cause to him, thus obtaining an early discharge or even a modest improvement in their living conditions.

None of this had been possible. The august man had turned out to be deaf, blind, and mute. A veritable ghost.

Would he also be like them in a few decades?

Would his body have withstood an existence of toil and hardship?

As he asked himself those terrible questions, Postumus caught sight of Aquilius' silhouette not far away. As he had done with him before, the veteran was trying to encourage his companions more by gestures than words, with soft pats on the shoulders and playful jerks.

Intimidated, he flanked him without saying anything waiting for the latter to notice him. It was not long before this happened.

But when their gazes met, Postumus realized that Aquilius was consoling others so as to lift his own mood as well. In his eyes, he glimpsed the same disappointment that others had openly manifested.

He wondered, knowing that he was indebted to him, how he could help him and restore his confidence. But once again, he found himself utterly bereft of meaningful ideas and words.

And after all, how could a recruit have spurred on a soldier who had fought a thousand battles? It was simply absurd.

Aquilius sensed his thoughts, however, and barely rippling his lips he showed him his gratitude for what he had hoped to do.

He abruptly encircled it with his right arm, giving Postumus a chance to count the endless deep scars that covered it. Then, spinning it with him, he pointed it toward the spot where Alexander Severus' chariot had disappeared.

They spent a few moments in silence, staring at the fog bank that grew thicker and thicker, like a sturdy trench protecting the camp of XXX Ulpia Victrix. Finally, he spoke to him.

Quietly and firmly at the same time. Exactly as a father would have done with his own son to teach him a hard but invaluable lesson.

"You can learn even from dark days like this, Postumus. So remember well the sadness you see in our eyes, so you can look at life realistically. The truth is that in the world there are ordinary men like us, who tread this very ground, and others who were born to walk several meters above it without ever soiling their shoes. The latter have never cared for us, nor ever will. Alexander Severus belongs to this small circle. So never seek their esteem or approval, or you will waste precious years in vain. The powerful people who represent the empire we strenuously defend have neither time nor desire to listen to our arguments. It will be your job, and no one else's, to fight for everything you want and deserve."

IV

A nobler cause

Matiscus, September 233 AD.

The sound of hooves pounding on the gravelly ground, constantly moving piles of earth, entered his brain. In theory, this should have distracted him. But incredibly, it had the effect of making Postumus concentrate even more.

He kept his gaze fixed ahead. The two padded silhouettes, supported by wooden poles driven into the ground, grew larger and larger as he moved forward. And then.

Beyond these, where the camp ended and a forest of ancient oaks began, was the last target. He almost had the impression that it was tacitly challenging him, inviting him to face it as soon as possible. Contracting every muscle in his body, Postumus accepted that appeal without delay.

He slipped between the first two silhouettes, which were supposed to represent two enemies, and carried out the instructions given to him.

He delivered a horizontal slash toward the one on its right, opening a gash where its belly should have been. Then, as he sheathed his weapon, he pulled the reins to himself and intimated to the horse to turn in the opposite direction. He stretched out his left arm and juggled the bronze shield between himself and the fictitious enemy, generating a shock that, however, did not move him in the least. His balance in the saddle wrung a few grumbles of appreciation in the older legionnaires, who gathered to observe how he would fare.

Almost, the wooden pole did not break in two: a sign that Postumus had impacted with impressive force.

He was amazed, too. But soon the surprise turned into fire, into a growing conviction in his own means that made him eager to finish. He therefore let go of the right grip, guiding the animal with one hand.

The steed barely snorted, but seemed to trust his guide.

Then Postumus growled, thrusting his heels into his hips and spurring him to accelerate by galloping straight ahead.

He saw the last silhouette getting closer and closer, while remaining motionless. He did not care about that paradox. It was not important.

It only mattered how he would perform in the next few seconds, and whether he would gain the esteem and respect of the veterans.

Without turning around, remembering the mechanics of the gesture by heart, he slid his right arm behind him and took an arrow from the quiver. Then he also let go of his grip on the left bridle, and in an instant reached for the bow.

He nailed the dart with such speed that this time the murmurs became shouts of encouragement. Then he knew that the time had come.

Gripping the horse's flanks with his legs and using all his strength, he ordered him to stop. The beast, however, reacted badly to his order, hoisting himself up on his hind legs and making his blood run cold in his veins. He had not anticipated it doing its own thing.

Everything began to dance around him because of the poor balance. The companions, the ground, the trees all around.

His ultimate target.

But he could not have concluded, nor said he was satisfied, without attempting to strike. So he appealed to all his coolness, and despite the precarious position he did as he had learned.

The arrow went off, with such a strong recoil that he was nearly knocked out of the saddle. With a hiss, this one cleaved the air.

And before Postumus could rearrange himself, becoming master of the mount again, he went and impacted the puppet.

Sticking exactly in the center of his head.

A prodigious achievement, given the situation, and one that sparked the enthusiasm of all those who had witnessed it.

Amid booing and roaring applause, Postumus regained the reins and looked around bewildered. But mostly, happy.

In the no longer stern but rather proud looks of the veterans, he discerned the appreciation he had been chasing for a year and a half.

During that time, he had practiced day and night to prove himself worthy of their advice and time.

And apparently, he seemed to have succeeded.

He left the animal with the grooms and slipped off his helmet with a sigh.

He was drenched in sweat and his hands were shaking. Yet, he had never felt so good since he had been recruited.

According to the dictates of the augustus, legionaries were to learn to evolve. In the vision of Alexander Severus, these were to excel both in the use of the bow and in mounted raids, transforming themselves into the multifaceted, armored figures that were coming so much into vogue. The cataphracts.

Thanks to them and the resulting mutation of the Roman army, the emperor was confident of routing both the Sasanids in the East and the Germans who so distressed the West.

Yet as he sat down in anticipation of the next exercise, Postumus told himself that that was not the reason for his commitment. Even in his early days as a recruit, he had been influenced by veterans and their bitter disillusionment.

Committing oneself to the empire was honorable, but it was not everything.

And so it had become for him as well.

Inside, Postumus knew for whom he was sacrificing himself.

He did it for his family, still mired in the Gallic countryside and forced into a miserable and uncertain life. But he also dreamed, with his future deeds, of redeeming all the bistratted and marginalized Batavians, of bringing luster to those brothers and sisters faceless and obliged to menial jobs stingy of satisfaction.

There was no telling when his time, his chance, would come. For that he had to be ready.

He would have had no choice after all.

So like those puppets, every opponent he would take down would reduce the distance between him and the peaceful future he had dreamed of since childhood, pining for the hardships of his loved ones.

Thinking of distant affections, he ignored the compliments and bowed his head in an attempt to hide his emotion.

It was for them, for his loved ones, that he was doing all this.

They were his empire.

And Postumus would protect and honor them no matter what.

They had his word.

V

The occasion

Surroundings of Lutetia, January 234 AD.

Stumbling and timidly using his elbows, Postumus finally managed to sneak into the huddle of men that had become the beating heart of the camp. It had all happened quickly, but in a manner striking enough to attract anyone's attention. Him included.

All he knew was that suddenly someone had appeared in the vicinity of the most marginal tents, and that his bombastic coming had aroused collective interest if not outright hysteria that was unjustifiable to him. But his legitimate misgivings vanished in a flash when he was able to catch a glimpse of who had really sought shelter among them.

Enduring a few jostles and blows to the ribs, he made it to the front row. A few steps away from him, a horse with its belly still distended from labored breathing sought the strength to graze the little that the stingy ground afforded it. Its grayish coat was glossy, and dense swirls of smoke rose from its exhausted body.

But the real attraction was even closer. For sitting on the ground, with his elbows resting on his wide legs, was a man.

Indisputably a Roman, judging by the lorica and the frayed plume on his helmet. These immediately seemed to him more tired than his own steed, with yellowed, bulging eyes and an emaciated face smeared with dirt and sweat.

He wearily held a bronze cup, which must have been filled with water and which he had already promptly emptied.

He looked at the legionnaires dazedly, searching for the words he had been mulling over all that mad rush and which now fatigue seemed to want to mockingly snatch from him.

Stooping over him, Postumus recognized Aquilius and a host of other veterans he now knew well.

Other soldiers crowded all around, to the point that he was almost pushed to the rear again. With a little malice, however, he managed to maintain that privileged position of his.

"I'm telling you...they have trespassed, east of Argentoratum. They are now officially in Gallic territory," said the newcomer all in one breath.

"And how many are there?" he was asked.

A messenger came from one of the border towns.

This is who he must have been. He must have covered miles and miles in a very short time, knowing that by alerting neighboring troops in a timely manner he could avert a genuine catastrophe.

Posthumously, at the thought of an unnamed enemy about to overwhelm them, he was overwhelmed with both concern and excitement. That the battle was just around the corner?

He thought about it with such ardor that he could no longer concentrate on the speech he was witnessing. He did, however, manage to hear a word, or rather a name, that made him vibrate from head to toe.

"Alemanni," the messenger said distressed, widening his eyes. "There are thousands of them. You must intervene."

The silence that fell made him realize the gravity of the situation. A barbarian army had forced the borders and was aiming to penetrate the Gallic province. A terrible scenario, and one that rightly would have worried anyone. But not a teenager who dreamed of distinguishing himself by fighting for Rome.

Therefore, of all the legionaries, Postumus was the only one who smiled.

No one noticed the gleam in his eyes.

How good it would have been, at last, to be able to establish himself as a valiant defender of the empire!

It was everything he had always dreamed of.

Only one person, Postumus told himself, could have understood his feelings, even if paradoxical given the circumstance.

And that person was a palm away from him. Eager and almost irrepressible, Postumus searched Aquilius with his gaze.

And he prayed that the latter would seize his enthusiasm, doing his utmost to give him the opportunity he had been chasing until then.

VI

Posthumous desire

Surroundings of Lutetia, January 234 AD.

"Why are you ignoring me?"

Aquilius stopped suddenly, just as he had reached the edge of his own tent. Turning around, he found Postumus standing in front of him.

Covered in sweat, panting and with clenched fists. He understood from his fiery gaze what his true intentions were, but kept silent.

"Don't pretend you don't understand," insisted the boy, taking another couple of steps in his direction.

But in truth, the veteran understood. He had noticed how the young recruit had stared at him, in those moments when the whole legion had learned of the impending Alemannic threat.

But he had deliberately avoided his gaze, convinced that there were far other priorities to give his attention to.

That sham, however, could not have lasted much longer. He confronted him, flaunting calm disbelief.

"What are you talking about, Postumus?"

"You know very well what I am referring to. I think it has been far too long. Now comes the opportunity I've been waiting for a long time. I want to become a mule."

In another context, that phrase would have sounded ridiculous and meaningless. But not within the XXX Ulpia Victrix.

That statement had a very specific meaning, and one that was completely impossible to misunderstand. Quite simply, Aquilius had tried to escape from such a responsibility.

An escape that was no longer possible for them. Not with an ocean of barbarians within striking distance of them, a situation that made it essential to arm even the most acerbic of men at their disposal.

Yet to the last Aquilius tried to evade that decision.

"A mule?" he repeated passively. "I don't think you need to call yourself that to highlight your merits. We all know that you are a hard worker."

Postumus gnashed his teeth, tired of being teased.

"Do you really want to mock me? Have you perhaps forgotten what that name means to you Legionnaires?"

Of course, Aquilius had not forgotten. From the day of its formation, the members of the legion had been called "Trajan's mules," an appellation intended to celebrate their blind devotion to the emperor that had made them valiant defenders of the empire.

The truth was that he still feared compromising that boy by officially including him in their ranks. His talent was crystal clear and undeniable, however....

Postumus had no idea what it meant to deal with those primitives, those voracious and unstoppable beasts.

He looked for words to put him off, but was interrupted again.

Nothing would ever again separate Postumus from his personal goal.

"I also know that there is no one in charge of this legion," he growled. "At the moment, the august has not designated any legate to make the decisions. Therefore, all responsibility falls to the senior centurion, the primipilus. And this happens to be you, Aquilius. You alone have the power to make me a member of this glorious legion. You need men now more than ever. And in these months I have proven that I deserve this opportunity."

Giving in to the evidence, the veteran bowed his head and looked at him intently. He knew he owed him an honest answer.

"You are still so young, Postumus...you have your whole life ahead to earn good money and cover yourself with glory. I think that..."

"I don't care about money!" ranted the boy, spreading his arms wide and screwing up his face. "I am not thinking of a salary, but rather of what I have always dreamed of. To put myself on the line, to fight for Rome and for my people who are part of this immense empire! How long will you keep me in the shadows? Have I not proven my abilities?"

How can you blame them?

Everyone in the camp appreciated Postumus and wished him a brilliant career. And no one cared more about his future than Aquilius. This was precisely why he had tried to protect him, while waiting for a more affordable opponent who would allow him to learn without exposing himself to too many risks.

But would that ideal circumstance ever occur?

It was also true that the legion, at that time, needed all available personnel. Regardless of their age or experience.

Suddenly, Aquilius realized his back was against the wall.

And to have to, by virtue of his role, make a choice. Even though he never wanted to take on such a responsibility.

"Don't you value your life?" he asked him in a low voice.

"It is the exact opposite, centurion," hissed Postumus, now calmer. "I care about it more than anything else. That's why I want to punctuate it with success. But if I never get the chance I deserve, how will I emerge?"

Yielding to transport, his clear eyes moistened. And then, in a last and desperate attempt to convince Aquilius, Postumus bowed his head making an act of reverence.

"Please," he whispered, now bereft of strength.

For a moment, Aquilius saw in him again a younger version of himself. He, too, had been like that: daring, madly loyal to the empire, infatuated with the idea of a bright future.

The hard life of a man-at-arms and the deaths he had witnessed had then stripped him of that feverish enthusiasm. But he could still understand those feelings, appreciate them, in a sense share them.

No, he certainly would not be the one to clip that boy's wings.

Then, abandoning all reluctance, he decided to give in.

But not entirely. Or at least, not at that particular time.

"I will do what I can, Postumus."

He told him this while barely smiling at him, but maintaining a harsh and stern expression as if to warn him about the uncertainty of that outcome.

Still, he could not help but discern the newfound joy in that boyish face that had once been his. Posthumously he already knew.

His time had now come.

VII

A just reward

Surroundings of Mogontiacum, February 234 AD.

Gaul was beautiful in spring and summer, with its lush forests and valleys in bloom. Even in autumn, despite the harsher weather and frequent rains, it retained something poetic.

But the same could hardly be said of winter.

The coldest and harshest season was capable of stripping away all color, plunging him into a seemingly eternal fog. The beautiful landscapes became bleak and confused, the soil depleted, and the most innocuous sounds became sinister dirges.

Distant, chilling chants, like those the barbarians intoned during their advances. With limbs numb from the long ride, Postumus recalled the hundreds of tales he had heard in the previous days.

There seemed to be no end to the nefariousness of which those people were capable. In front of faint fires, he had listened raptly to the anecdotes of those who had already faced them. He had immersed himself in their still-shaken gazes, enlivened by the uncertain dance of the flames.

And he had taken to imagining enemies as monstrous creatures, with human features but hardly resembling them.

The memory of the bestialities he had heard about made him shiver. Squeezing himself into his cape now soaked with moisture, he turned his gaze to the fog banks that concealed the horizon from them.

That the Alemanni were hiding behind that milky barrier? Were they perhaps ready to attack them?

It is difficult to determine. One thing, however, was certain.

Those demons had violated the sacred borders of the Roman Empire, penetrating Gaul and threatening to put it to the sword.

For that reason they had been marching for days in the direction of Mogontiacum, where they had last been spotted.

It was essential, Aquilius had declared, to reach the city before them so that the border could be secured again. That stretch was in fact littered with important settlements, and surrendering even one of them to the Alemanni could have started a very dangerous chain reaction. The empire could not show weakness or submissiveness, or else the other barbarian peoples would have seized that signal by rediscovering long-dormant appetites.

As he pulled up with his nose, increasingly irritated by that cold that gave him no peace, Postumus wondered how it was possible that a people so close to his own people, the Batavians, could still live so savagely.

While they had adapted to the laws of the empire, seeking to coexist with the Romans, the Germansc tribes still lingered in a primitive and anarchic life, abhorring the benefits of civilization.

Would it ever be possible one day to help them redeem themselves by making them a valuable resource for the common good?

His horse roused him from those thoughts, perhaps too deep for a boy of his age. Nitrating, the animal snorted and chased two dense clouds of smoke from its froge.

That so common and seemingly insignificant gesture brought him back to reality. A reality that for him still seemed like a dream magically fulfilled.

He looked around, finding the very long theory of legionnaires striding wearily toward a still distant Mogontiacum, or perhaps closer than they thought.

Those who, unlike her, were not on their first campaign seemed extraordinarily far removed from what awaited them. On their hard faces there was not the slightest trace of tension or impatience for that confrontation that could have erupted at any moment. Postumus endeavored to imitate them, keeping his back straight and trying to replicate their expressions not at all troubled.

But he soon realized that this would be impossible for him.

His state of mind was completely different from that of his fellow soldiers. And it could not have been otherwise.

Letting the fire that blazed within him permeate him, he scrutinized himself with newfound wonder.

He contemplated his gleaming armor, studded with the drops of water generated by that damp and icy atmosphere. He was elated at the sight of the short sword hanging from his belt, and he was even moved to look at his muddy shoes and worn reins that gave him total mastery of his horse.

Everything around him reminded him of the extraordinary adventure he was about to experience. A knot formed in his throat, then, when he met the banner of the legion a few steps ahead.

Although he did not garrulous, complicit in the absent wind, that symbol that now also represented him made his heart flutter. He almost had the impression that the capricorn depicted there could come to life from nowhere and begin to leap between them.

He had finally succeeded. He was officially a member of the XXX Ulpia Victrix. And it didn't matter that he occupied the lowest position in that complicated and dense military hierarchy.

Soon, he too would be able to make his contribution to the peace and prosperity of Rome's glorious empire.

Those moments when everything seemed so alive and projected toward future glory were enough to redeem all the hardships and humiliations suffered along the way. For the first time, Postumus felt truly close to making his family, which he had left months earlier with the promise of making a name for himself, proud.

Would he ever see them again?

Or would his audacity have cost him his life?

It was always terrible to ask such questions. But for once, Postumus managed to do so without feeling his legs shake.

He had deserved that priceless opportunity, and he would not waste it. Against all odds, he would take his life in his hands and do what he could to make it what he dreamed of. A flock of crows crossed the sky unseen, cawing unpleasantly. It seemed to him, for an instant, that he had heard one of the war songs of the Alemanni.

And that was helpful for him to refocus on his goal.

He would not allow any enemy to snatch from him that opportunity for which he had fought so hard.

VIII

The horde

Surroundings of Mogontiacum, February 234 AD.

He had seen the Rhine only once, as a child. His father had taken him near the West Bank on a summer day, but of that happy event Postumus remembered little or nothing.

And even if he had remembered, surely what was in front of him at that moment would have been the farthest image from that already fading memory. The river that marked the boundary between civilization and barbarism, between empire and the wild world of the Germansc forests and grasslands seemed to him more like a sea.

He gazed petrified at that seemingly endless expanse of pearly, seething water that kept turning over its bottom, bringing mud, branches and debris to light. It seemed to him almost like a formless monster about to devour everything, even the pasty soil they were treading. But there was something far worse than that thought. A threat that was undeniable, concrete, and would soon be tangible.

In recent days, plans had changed. Mogontiacum, thanks to extraordinary recruitments, had no longer been declared at risk.

The city most in danger now was Bonn, which was a scant distance from where they were camped. Under normal circumstances, the legion would have reached it in little more than a day's march. But Postumus only had to look at the worried faces of the more experienced soldiers to see that this was not going to happen.

And just what had stood between them and their designated destination. A veritable human wall, composed of shrieking, gigantic men who seemed ready to pounce on them at any moment.

Not even having the Rhine behind them and a legion a few hundred paces away seemed to intimidate them.

The Alemanni had managed to intercept them prematurely.

And they were ready to give battle.

Trying to ignore their hoarse chants and sporadic barbs, Postumus carefully observed their features. And he told himself that he had never met such terrifying men. The first thing that struck him, beyond their stench that was discernible even from a distance, was the fact that they wore no protection. Some of them, with their faces, limbs and chests covered in indecipherable designs, were literally half-naked. Only ragged flaps of fur covered their genitals. But some had given up even that superfluous hint of modesty, braving the elements as a wild animal would have done.

Their complexion was remarkably pale, but not a sign of weakness. There was not a single legionnaire around him who could compete with them in stature or muscle mass.

Those energy-spewing limbs must have been forged by nomadic life and its daily challenges. They also had no self-care whatsoever, judging by their frizzy, matted hair, left loose or gathered in braids. Many among them had them the color of gold or copper, shades highlighted by their crystalline eyes and fierce expressions. Postumus tried to count how many there were, but ended up being mesmerized by their chants and the constant twirling of the clubs and blades with which they were equipped.

Noticing their growing agitation, he felt himself failing.

And he was supposed to stand up to those furies?

He was discouraged, then, by the visible tension of his fellow soldiers.

If those men, after a life spent fighting, were so ensnared by the enemy this one must have been truly fearsome.

Returning the shy and bewildered boy he had always been, Postumus did the only reasonable thing at that juncture: he went in search of security from the only individual who could give it to him.

Before long, he found himself at the side of a busy Aquilius making arrangements for those around him.

"We will wait for them to make the first move," he heard him say. "What is certain is that we will never reach Bonn without leading the way by fighting. At this point, it would be foolish even to send messengers to request help. So let's get ready to...Posthumously? What are you doing here?"

"How many is that?" he asked in an indecisive voice, not hiding the boyish innocence in his words.

Rubbing his cheeks covered with a shaggy beard, Aquilius took a quick glance at the Alemanni pawing in the distance.

"Do you really want to know? Look there," did the veteran, pointing to a small hill to the east.

When he laid his gaze on it, Postumus paled.

That soft slope appeared to him to be littered with other barbarians, intent on descending it to replenish the already nourished ranks of those who had stationed themselves in the valley. At a glance, he had the impression that there were several thousand warriors. An ocean of half-naked bodies, sweaty and euphoric, eager to feed on their flesh.

Nothing in them could be said to be human.

Instinctively tightening his grip on the belt from which his sword hung, Postumus tried to remain firm on his legs. But Aquilius immediately noticed his pallor.

That was exactly why he had wavered so much before officially enlisting him: he had grown fond of the boy, and he would never want to give him to those beasts.

"They are...so many," murmured Postumus without taking his eyes off them. His head trembled slightly.

"That's right, son. Do you have any idea what would happen if they were able to break through, penetrating to the heart of the province?"

Postumus did not answer, but gave him a terrified look.

Aquilius then tried to instill confidence in him, appealing to the pride with which he knew him to be endowed.

"That is why we must defeat them at all costs, although it will certainly not be the last time we meet them. We are called, today as many times before, to protect Roman civilization and peace within the imperial borders. This is our task, and now it is yours as well. Become aware of it, Postumus. Being a member of Rome's glorious army requires more than knowing how to wield a sword well. Now get back into position. And be ready."

IX

Dreams of a veteran

Surroundings of Mogontiacum, February 234 AD.

Postumus stood in a daze, staring at the fire and the sparks that faded as they went up into the darkness around them. He drank, almost unconsciously, another sip of the soup that had been distributed to all the legionnaires on guard duty.

The rancid aftertaste of the slop had an effect as invigorating as it was paradoxical on his tired limbs. Blinking several times, he escaped the languid grip of sleep and returned to reflect on what had happened that day.

He had believed he was nearing his debut in the ranks of XXX Ulpia Victrix, and for long moments he had been torn between the urge to prove himself and the temptation to run away.

Finally, ashamed of those cowardly thoughts, he had gotten into position, trying to prepare himself as best he could.

But then something had happened. An unexpected event, in some ways silly, but one that had completely upset the plans of both sides. A member of the Alemannic rearguard, perhaps inebriated or simply distracted, had put a foot wrong where the bank of the Rhine was still unstable and slippery. His had been an awkward and ungainly fall, but also a lethal one. For that ruthless and roaring river had swept him away with the force of its incessant billows.

A Roman would have looked at it as a misadventure, or as the just punishment for that careless and reckless warrior.

But the Alemanni had given the event a far more sinister and darker meaning. Suddenly, these had begun to move away from the river with increasing agitation. The fury in their eyes had given way to sheer terror, and in the space of a few minutes Postumus had seen them almost hastily abandon the portion of the plain they had occupied.

An inexplicable gesture, an absurd escape considering the numerical superiority they boasted against them.

Why had they run away? What had they seen in the Rhine so terrible that they had given up fighting?

He asked himself that question to the point of exhaustion, to the point of not noticing that the comrades engaged in the same shift as him had already headed to their respective posts. Had it not been for the rough pat on his back, Postumus would have remained staring into the fire until dawn.

"You can't explain what happened, can you?" a voice behind him asked.

"Not at all," sighed Postumus, recognizing Aquilius.

The veteran sat beside him, his legs spread wide and his hands clasped over a cup filled with steaming wine. He handed it to the young comrade, who willingly accepted the offer.

"It was all the fault, or perhaps merit, of that warrior who fell into the river. You should know that barbarians obsequiously worship the forces of nature, and believe that these are real deities capable of punishing men and giving signals about future victories or misfortunes. Seeing their comrade swallowed by the waters, these people thought that the river deity was warning them about their mistake in crossing it. And so, they preferred to retreat rather than further draw its wrath by persevering in their plans. And honestly, this was very fortunate for us. Remember, Postumus, that barbarians are superstitious to the point of dullness. And this for us Romans is a valuable weapon that we must learn to master as much and more than the swords we wield so skillfully."

So had that been the reason for the lack of conflict?

Stunned and perplexed, Postumus stared wide-eyed at Aquilius. An event as futile as one man's distraction had been enough to save thousands of lives.

And all because of the distorted perception of those primitives.

He would have liked to comment on it, to ask for more information about the customs and beliefs of that fierce yet naive people. But fatigue from that prolonged vigil got the better of him, causing him to fall silent.

Aquilius, however, still felt like talking. And to make confidences.

"The more you learn, boy, the sooner you will mature. And I hope that will happen quickly, because very soon I will no longer be here to advise and follow you as I am doing."

That hint was enough to abruptly awaken Postumus. He turned sharply toward what was now his mentor.

"What do you mean?"