2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Patrizio Corda

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

407 AD - Britain is now in chaos, abandoned by a Western Empire

unstable and besieged by hordes of barbarians threatening its borders.

Exasperated, the people cries out for leadership after the death of

Magnus Maximus, the last great to rise against the Theodosian dynasty.

The troops elevate several soldiers to the purple, causing them to fall shortly thereafter. Only one of them, Constantine III, will succeed in uniting all Britons under himself, involving them in his project of total reform of an empire now dying and destined to disappear.

From the misty, dark seas of the North, Constantine will land across the Channel, shaking up the empire in an attempt to make Britain the epicenter of a new world, founded on the ashes of Rome.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

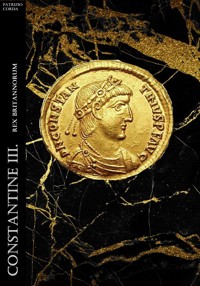

Constantine III. Rex Britannorum

Indice dei contenuti

CONSTANTINE III. REX BRITANNORUM

Patrizio Corda

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

XLV

XLVI

XLVII

XLVIII

XLIX

L

LI

LII

LIII

LIV

LV

LVI

LVII

LVIII

LIX

LX

LXI

LXII

LXIII

LXIV

LXV

LXVI

LXVII

LXVIII

LXIX

LXX

LXXI

LXXII

LXXIII

LXXIV

LXXV

LXXVI

LXXVII

LXXVIII

LXXIX

LXXX

LXXXI

LXXXII

LXXXIII

LXXXIV

LXXXV

LXXXVI

LXXXVII

LXXXVIII

LXXXIX

XC

XCI

XCII

AUTHOR'S NOTE

THANKS

Literary property reserved ©2024 Patrizio Corda

CONSTANTINE III. REX BRITANNORUM

Patrizio Corda

To my sister

I

Sons of Rome

Eboracum, March 374 AD.

The fog completely covered the horizon, settling like an immovable monolith on the still frost-covered meadow.

Slowly, dark silhouettes emerged from the banks of mist, heralded by their cadenced and uniform step even before their own outlines. The legion thus showed itself, like a theory of ghosts rising from the deep and uncharted waters that surrounded the island, to the inhabitants of Eboracum.

Faces covered with scars, unkempt beards, wrinkles as deep as furrows in the fields prepared for the harvest of a few benevolent months.

The clinking of weapons that hung at the soldiers' flanks like an echo, a reiteration of their arrival sentenced by that gait. Silent, granitic.

The inhabitants of the Roman city and fortress responded in turn with a heartfelt, respectful and grateful silence. Not a cry, not an acclamation or a gift. Just a silence filled with meaning. In the middle of that human river, like a purulent appendage to spoil the harmony and order of that march stood a huge group of war hostages. Hirsute hair, very long beards, truculent eyes and gigantic physiques covered in a few skins and rags.

Picts.

The worst of the peoples inhabited the dark and desolate moors of northern Britain, beyond the Wall of Antoninus. Those barbarians had done nothing but sow death and destruction with each of their descents, to the point of requiring the intervention of troops stationed everywhere throughout the island. And that had been the result.

The Roman armies had slaughtered all the tribes in front of them, and now they were returning to Roman Britain, the civilized part of the island, with them a large booty of human lives that would bring the empire substantial revenue with their resale in the slave Marcusets.

With his senatorial toga and cloak girded up to cover his nose, Flavius Claudius Ambrosius kept his gaze fixed on the military men who cut the city in two with their passage, barely suppressing shivers from the chill made even more unbearable by the morning humidity.

Fortunately, there still remained the legions. Otherwise, the whole of Britain would have ended up at the mercy of those people utterly divorced from civilization, accustomed only to massacres and rape.

To tell the truth, in the meetings he had always attended in the city palace, he had always wondered, extending his doubts to the other honorable members of that assembly, whether the monumental valleys built by the emperors Hadrian and Antoninus in previous centuries would still be sufficient to contain the offensives of those peoples. Nevertheless, in addition to the Picts, the Saxons had also begun to press insistently, often landing on the island's shores.

It seemed that those grand works of the past, those immense walls studded with forts, could no longer hold, as if destined to be overwhelmed by the human tides that were said to lodge beyond their borders, holed up in mountains and forests.

Everyone had always denied the catastrophic prospect of an invasion, but the news coming from other imperial regions did not bode well. The empire that had once had secure borders, large enough to see the sun rise and die within them, now had to defend itself against the barbarian hordes that had emerged from the remotest lands.

And it was not just about Germans.

He had wanted to attend the passing of the legion, of the invincible soldiers of Rome, the Urbe of which he felt fully a part, to understand. He wanted to see for himself the forces entrusted with safeguarding the empire, the world in which he lived.

Yet, even in the victory of the moment, he glimpsed tired faces, tried by constant hardships. He often crossed the gazes of veterans, discerning in them a desire to get to their discharge as soon as possible to escape from that life made up more of hardships than of honors and recognition. It did not seem to him a pretty sight at all.

He seemed to see a tired and impatient master trying to tame a tireless and furious beast, a wild horse impossible to saddle and tame in any way.

The Picts would fall silent for a few moments, then go back to wriggling, throwing unintelligible noises trying to free themselves from the knots, until some soldier struck them, bringing them back to calm.

There could be no room in the empire for such beasts.

He had seen enough.

The frost was causing his fingers to lose feeling in his hands, seeping into his temples with excruciating pangs as his barely open eyes grew dryer and dryer.

He had hoped to witness a triumph, but instead he had seen a mournful procession of very unmotivated soldiers and men-if men could be called them-destined to be little more than objects, meat for the slaughter.

He wondered to what extent those positions would remain so and whether they would ever be reversed. The prospect gave him another, far deeper thrill that made him realize he had reached the limit of his endurance.

He then turned around, heading expeditiously toward his residence. He had taken far too much time away from what should have been his real priority. His wife had now reached the top of her pregnancy, and would probably give birth to her firstborn that same day.

And he wouldn't have missed that scene for the world.

II

The fire

Adrianople, August 9, 378 AD.

It seemed to Valens that the end of time had come.

Selfishly, he was pleased to be on the verge of death so that he could avoid seeing everything end, unravel, reduce from the most resplendent magnificence to a pile of ashes.

He tried to move his right hand to try to feel the wound in his side that he could still feel bleeding profusely, but he could barely move his fingers. He gave it up sadly.

He never thought it would end like this.

The decisive battle to defend the borders of the empire had been lost miserably. And the blame was solely his own.

It was he who had thought he could subjugate the Visigoths, opening the gates of the empire to them and then make slaves and laborers of them.

It was he who had entrusted the management of the refugees and military operations to Lupicinus, accepting that he then tried to treacherously kill the barbarian leader Fritigern. The failure of that conspiracy had unleashed the fury of the Visigoths, who then rose up in arms against Rome.

And always he had agreed with moving troops against the enemy without waiting for the Western Emperor, Gratian, to come to his rescue so that he could fight the enemy in considerable numerical superiority.

He gasped laboriously, breathing raggedly, as he felt the strong, nauseating taste of blood fill his mouth.

And so his forces, the forces of the empire, had been routed by the Visigoth horde that had seemed invincible. Even when there had been a chance to retreat and save thousands of lives while awaiting the arrival of Gratian, he had decided to press on, to engage in battle in the hope of triumph. He, and that was it.

His inordinate ego had lost him. This was.

When he had been wounded he had been immediately taken to his tent. But then the Visigoths, having exterminated almost all his men had come there as well. He had realized this, though partly unconscious, when he had seen doctors and servants fleeing without telling him anything, while he had felt a growing heat all around.

The barbarians, without even knowing who was in it, had set fire around the tent. What fools!

How much booty they had just lost! Not to mention the honor in being able to hoist the august one's head on a pike!

And he, Valens, the lord of half the world, had lost to such naivete. He had let tens of thousands of valiant Roman soldiers be killed, torn to pieces, and then vilified by that horde of beasts that had nothing human about them.

What a strange feeling it was, in that frantic overlapping of present and past images, to feel the cold sweats that acted as an antechamber to passing away while everything around burned inexorably.

Valens laughed. Yet he cried.

Within moments he realized he could no longer feel his legs.

His body now abandoned him, and he wondered if once he died the Lord would not abandon him in turn, unable to forgive him for his folly.

He had longed to be the proponent of one of the greatest military victories in history, but instead he would be remembered by posterity as the perpetrator of a shameful and senseless extermination.

Perhaps, even of the end of the greatest empire ever.

What's more, his hated colleague Gratian would come out as a misunderstood hero, blameless in the face of that catastrophe.

Now the Visigoths, and with them all the other barbarian peoples, would realize that Rome was not invincible. Not anymore.

If decline and the end of everything would be, the fault would forever be his. And no one else's.

Unintelligible screams came to him from outside. Animalistic grunts, guttural cries of joy, almost more like howls than words.

Would the world have belonged to these people from that day forward?

What a disgrace!

Valens saw everything shrouded in fog. He thought first that it was the smoke, then the tears he could no longer hold back in shame, but then realized that he was simply bleeding to death, and that he had no strength left.

His time had almost come.

He would have liked to take his own life, making a final gesture that would remind him that he was a Roman, the first of the Romans, and as such a certain dignity and morality were imposed on him.

But he could no longer. He was already paralyzed. Reduced to a larva.

An end under the banner of extreme ignominy had been decided for him, as punishment for the insanity that generated his actions.

And he deserved it, after all.

Who knows if all those people he had chosen to elevate to the highest positions in preparing for that battle had been saved.

He would have liked to resent them, but too much he had done himself to be able to place even a single blame on anyone other than himself.

Just him.

The tent began to burn. The flames were devouring everything.

He had no strength left. At that point, he closed his eyes.

Let them devour him, those flames.

And that they would cleanse his soul of the sins he had committed.

The crackling, along with the external screams, overpowered everything.

Before remitting his soul to God, he prayed that Rome and the whole empire would not suffer the same fate as he did.

III

Dreams

Eboracum, June 380 AD.

"So you want to be a legionnaire, kid?"

Constantine widened his crystal-blue eyes and nodded vigorously, shaking his raven curls. He held out his hand without any embarrassment. The soldier straightened up and laughed.

"Do you want this?" he made, pointing to the sword he held at his side. Constantine nodded again, thrilled.

"All right," did this one, whose name was Gratian, handing it to him.

He burst out laughing as he watched the child struggle to even hold it in his hands, the tip crawling on the dirt.

"But it's so heavy!" he complained.

"It is still a bit early for you to be able to wield a weapon already, however, good will is always a great place to start," interjected the other legionnaire, whose name was Marcus.

The two had completely opposite features: tall, sturdy, broad-shouldered Gratian, with sparse hair and a strong nose, while Marcus appeared more petite, no less muscular but with elegant facial features made barely rougher by thick brown curls and a thick, bristly beard that covered much of his ruby face.

They had taken a liking to those two young boys who occasionally slipped away from the careful vigilance of the preceptors to sneak into their camp, nestled in a forest of ancient oaks.

The magical atmosphere of that fortress set in the wilderness must undoubtedly have had an influence on such young boys. And if Constantine was already known to most, being the son of a member of the Senate and scion of a noble family, they just couldn't figure out who the other child was, thin and milky-skinned, with thin grayish feline eyes and long hair the color of snow.

A lot was said about albinos. That they were children of forbidden unions between virgins and forest spirits, or that they were possessed by the devil and capable of dangerous and dark witchcraft.

Moreover, that serious attitude and his silence made him much less affable than Constantine.

Marcus knelt down in front of him. The child stared at him without a hint of emotion.

"What about you? Do you also want to be a legionnaire like your friend?"

"Yes."

Nothing else. Marcus wrinkled his forehead.

He was such a strange child.

"Yet you don't look like an equal rank to your comrade. What is your name?" intervened Gratian.

"Vortigern. My name is Vortigern."

From the harsh expression the latter turned to him, the two understood that the little one must have been the son of humble people, and not only because of the fashion of his clothes, which were far more miserable than the refined robes of Constantine, who meanwhile looked at him with pity.

He was certainly the son of Britons and not Romans. And he definitely had not appreciated their mention of his lineage.

"Come on, you take it too!" encouraged Constantine.

Vortigern gave him a barely-there smile, and unlike his friend he managed to hold his sword firmly, even sketching out some drawn blows in the air, albeit awkwardly.

"Not bad!" congratulated Marcus, trying to make up for the unfortunate statement his companion had made earlier.

The little boy did not answer him. He seemed lost in thought as he stared at his hand holding the sword. Then, as if nothing had happened, he stared at the legionnaire and handed it back to him.

"Can you take us for a ride?" asked Constantine.

That place looked fantastic to him. The weapons, the horses, the marching soldiers, the fortification itself with its stone blocks and palisades...it was a dream!

How he would have loved one day to be a member of the glorious and invincible legions of Rome, too!

"Claudius Flavius Constantine!"

Ambrosius burst in like a fury, covering the distance that separated him from his son with great strides. He angrily grabbed him by the wrist and yanked him to himself as the latter groaned.

Marcus and Gratian stiffened instantly. They didn't want any trouble.

"Senator..."

Ambrosius only seemed to notice them at that moment.

"I ask you to forgive me, soldiers. Unfortunately, this little boy is making me suffer more and more every day," he did, casting a fiery glance at Constantine, who lowered his gaze in embarrassment.

"But no, the guys didn't intend to bother us ... they were just asking us some questions."

"Questions they should ask when they are in class, assuming they are not skipping them on purpose!"

"Father, I..."

"Quiet! We will talk about this once we get home. I still ask you to forgive their impetuosity. You may return to your exercises."

The soldiers nodded, hinting at a bow.

"Let's go, Vortigern. You come with us too, come on."

The old-haired boy turned one last, cold glance at the two men, then lost himself scanning the ramparts of the fort.

He seemed attracted by the lone flight of an eagle crossing the cloudy sky above them at that moment.

Then, without saying anything, he took Constantine's hand and turned away.

IV

The twins

Caledonia, December 385 AD.

In the dense birch forest, where fog snaked through trunks and branches in the night, an imperceptible glow appeared.

Sheltered from any eye, in a tiny clearing was a stone altar, consisting of a huge monolithic block of a metallic gray. All around it, in a circle, tall giant stones, like pillars with no more roof to support.

A fire crackled on the altar, which was getting bigger and bigger. A few hooded figures were attending before it. A man of indefinite age, with a very long white beard, kept throwing dry branches and leaves over it, enlivening the flames.

He murmured formulas so archaic that they escaped the comprehension of almost everyone present, while with short, lightning-fast gestures he gathered ashes from the fire and scattered them all around.

His eyes were closed, his body swaying as if a wind only known to him was holding him up and levitating him according to his will.

He opened his arms and two orderlies, also hooded, handed him what he requested. The heart, still warm, of a deer.

He then turned toward the two figures further away, who discovered their faces. A man and a woman, still young, stepped forward, each of them with a child in their arms.

Not even the frost and the old druid's constant formulating seemed to be able to wake them up; on the contrary. That ghostly atmosphere seemed to have conciliated their sleep, instilling in them an unflappable calm.

The little ones were laid, as the swaddling clothes were removed from them leaving the little bodies completely naked, on the stone altar, not far from the fire that gave off fleeting bluish-white glows.

The druid laid his skeletal hands on each of them.

"Breanainn..." he whispered hoarsely.

The two young parents remained silent.

"...Maewyn."

At the utterance of their names, the children simultaneously began to weep, of an uncontrollable, broken cry, as if something, in addition to abruptly waking them from their sleep, was troubling them deep inside.

The druid then took the deer's heart and squeezed it with the pressure of his hands until the dark, warm blood that came out completely flooded the bodies of the two infants.

The mother of the little ones covered her mouth with her hand in fear as her husband held her close, trying to reassure her.

It was a dangerous ritual, a dark ritual, but it was what had always been done among their people, for centuries. Even when the peoples of the South had come to their lands and almost completely exterminated them. Still in those days they told of the wrath of Rome, the homeland of the conquerors who had almost wiped from the land and from the memory of all the ancient and sacred Druidic rites to which they had all been introduced within days of their birth.

That was the greeting to life for those children in the name of their ancestors.

The druid gradually raised his voice until he screamed at the top of his lungs, and a gust of wind hissed through the rocks all around, creeping everywhere through the forest.

He gathered a small leather bundle from a bag and opened it, then scattered its dusty contents over the flames.

These swelled out of all proportion as they came roaring up into the starry sky, surpassing in height even the tallest stones. The reddish glow of tongues of fire danced everywhere, spirit presences arrived among the men from their occult world. It was not for any of them the first time they had witnessed such a ritual.

But each time the magic took over, prostrating the spirits and causing everyone to surrender, reciting subdued and chanting prayers, to the sacredness of the moment.

The flames enveloped everything until they hid from view the little ones, who had meanwhile stopped crying, and the old druid, who raised his arms to the sky and in a heartbroken voice continued to shout his formulas to the stars, until a blinding glow plunged over the altar, taking away everyone's sight for a few moments as the roar of its impact expanded, fading in short order.

Moments later, a thick, pungent-smelling haze settled on the damp, cool ground, gradually revealing silhouettes.

"Did Eogan succeed you?" murmured the woman, anxious.

"Yes," her husband reassured her, squeezing her a little more. "He succeeded." A flash of pride flashed in his green eyes as the clouds finally cleared.

"Now our two beloved sons will also be druids. Just like us, and our fathers before us."

The old man was on the ground, exhausted, huddled in on himself as if humbling himself before the majesty of what had just been accomplished. On the altar the fire had magically gone out, leaving only the barely smoldering embers of itself.

There was no trace of blood on the stone.

Finally, the two children reappeared last, both lying down and slumbering again, with sweet, seraphic expressions on their perfectly identical faces.

The man and woman went to the altar as the hooded figures rescued Eogan the druid and lifted him up, trying to help him recover after that superhuman effort.

Under the stars of the remotest and wildest Britain, the two children were clothed by their parents, and then hoisted to heaven and thus consecrated to the immortal spirits who were everywhere around them, and whom they would serve until the end of their lives.

V

Predestined

Constantinople, January 386 AD.

"I have big plans for him."

Stilicho watched unpleased as Theodosius, the emperor of the East, watched together over little Honorius, the son of the august serenely sleeping, the plump oval of his face barely touched by a ray of afternoon sun.

At not even two years old, the child had already been appointed consul.

That noble and secular office, which required a lifetime of sacrifices and strategies to most to reach it, had been given to him as a gift, without much thought, by his father. Undoubtedly a political gesture aimed at strengthening what was to become, in Theodosius' plans, an indissolubly united dynasty of absolute power. The little one would grow up at court, in the heart of the Eastern Empire, and would learn early on how to move and how to interpret gestures and intentions of everyone around him.

But Stilicho was a barbarian. The most powerful barbarian in the empire, but still a step below any Roman who had pure blood. And even his already immense military merits and his loyalty to Rome could never have elevated him to such positions.

It was as if, although he was an important figure - indeed vital given the turbulence at the borders - of that world he was not allowed to be fully a part of it, always ostracized from the circles that really mattered and to which he aspired because of his origins. It was enough to mention these for his valor, military wit, pure spirit and honesty to fade into the background, leaving someone else with the honors of the limelight.

As in the case of that plump child, with long, somewhat messy black hair, resting blissfully on his side as he and Theodosius gazed at him.

Undoubtedly Honorius had taken after his father, both in the color of his hair and in his fair skin and face with soft, gentle features. There was little to say about Theodosius: his military career spoke for itself, and even on the throne he had immediately been able to impose himself with his political intelligence.

He had deserved the purple. That child, on the other hand?

Stilicho just could not explain why a child still unable to speak had just been made consul at the expense of dozens, hundreds of distinguished and deserving men.

Men like him.

But at this point he had to care only about military maneuvers since politically, he had to realize, he was worth less than zero. Theodosius, shrewd as he was, understood how delicate the situation in the empire was. The Visigoths who had destroyed Valens' army years earlier had been made to settle along the Danube, not without rightly fearing that they would repeat what they had done at the Battle of Adrianople.

In Britain, then, the legions had elected a usurper, that Magnus Maximus who had gone as far as Gaul and because of whom, during one of the later clashes, the Augustus of the West, the young Gratian, had perished.

When the empire had been divided into two parts, this had seemed the wisest choice to restore order in a political and economic landscape that was undergoing major changes.

Yet no matter how great the efforts made, new threats continued to emerge from the borders, and not only from outside, as witnessed precisely by the rise of Magnus Maximus, elected by the British legions themselves.

"You will see, Stilicho. The child, growing up from early on in a position of power, will naturally become an intelligent ruler who is perfectly comfortable making even the most difficult decisions, in whatever matters they may be."

Theodosius' eyes shone as he contemplated his son.

There was no doubt that with Honorius and his eldest son, Arcadius, the latter planned an empire ruled in all respects by the dynasty he had just started.

"I do not doubt it, holy august one. He will be a great ruler."

But he knew full well that he was lying.

It was not possible, indeed it was not the least bit logical to make such reMarcuss about what was barely an infant.

History, which he had learned albeit late but with great voracity, had taught him that Rome and its ruling dynasties had often known scions who proved unfit for government, if not outright degenerates across the board.

Caligula, Nero, Commodus, just to name a few.

Young men who had grown up at court, just as Theodosius wished for the small and innocent Honorius, who instead of becoming wise and moderate regents had wallowed in vice and privilege, exacerbating their turmoil out of all proportion once they attained power.

Often, even shedding blood in their own family.

Stilicho shook his head. Perhaps he was going too far.

"What are you thinking about?" asked Theodosius, who had noticed his silent brooding.

The Vandal felt caught in the act. He stroked his thick brown beard and smiled distractedly.

"To nothing, augustus. I was just thinking about what will be waiting for us now, with that Magnus Maximus in Gaul."

The emperor affably laid a hand on his shoulder.

"Don't think about it now, general. We will discuss this later with the guardians of the young august Valentinian. The statue I had erected for him will surely have calmed him down. Once we have decided what to do, you will return to Italy and oversee the expedition yourself."

"You honor me, sacred august," murmured Stilicho, kneeling down.

Just as well. He was looking forward to sailing to the West.

There he would return to what he loved, and at which he was the absolute best. Commanding the army.

Without imperial babies to rob him of his indisputable merits.

VI

A world to protect

Surroundings of Eboracum, March 386 AD.

Constantine handed Vortigern a still unripe apple. The young Briton bit into it without complaint, and stood staring at the verdant meadow as he let his bare legs dangle in the void.

Ever since they had discovered that magical and isolated place one winter day, they had made it their hiding place.

Chasing a roe deer, they had entered a dense forest of ancient oaks, arriving at a small and lush clearing, covered with clumps of green grass and multicolored flowers, into which it seemed as if the sun poured all its rays that could not penetrate the branches of the trees. In the center of the clearing were large stones, mostly laid vertically and in a circle and covered in turn by blocks arranged horizontally, except for one, gigantic one, laid in the center. On the frosty mornings typical of Britannia, ice covered them with a shimmering patina, emanating glows in all directions, ripping through the haze of the rising day.

"So those were temples?" asked Constantine.

Viewed this way from above, as they rested on the branches of a colossal oak tree, that building was even more impressive, with the forest tops all around and the mountain ranges on the horizon.

"My father always told me that it was in places like this that the druids, men with the gift of magic, performed their rituals. That is, until the Romans came."

"And then?" asked Constantine, leaning toward him.

"At that point, they disappeared. As the Romans conquered the whole island, the Druids holed up in centuries-old forests like this one. Some say they then disappeared altogether, or perhaps they were exterminated, which is very likely. Others even say they escaped beyond Hadrian's Wall and then Antonine's Wall to Caledonia. But since there are only Picts, Saxons and pirates there from the island of Ibernia, I doubt if they found any land to settle in."

"So they would be magicians..."

Vortigern shrugged. Nothing seemed likely to impress him.

"If you want to call them that," he said listlessly tossing the apple core.

Constantine leaned his back against the trunk of the oak tree.

He remained staring at the spectacle of nature, at the endless wonders that that enchanted island gave them whenever they decided to get away from the city to play, to exercise or even just to explore the surroundings and set their imaginations free. He loved that land.

"We are lucky to live here, Vortigern."

The albino gave him a look somewhere between wistful and excited. He was happy that his friend Romano appreciated the beauty of his homeland. Constantine was a good boy, loyal and able with his boyish enthusiasm to balance his reluctance and introverted being. Yet, knowing that the island where he and his ancestors had been born was dominated by the Romans did not entirely please him. Yes, they had brought civilization, culture and trade, but at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

The arrival of their culture, though enviable, had almost completely erased the traditions, myths and legends that only inside the homes of the natives, at night and with the shutters barred, dared to reminisce in front of the fires.

The courage of Boudicca, the fiery-haired queen who raised the Britons in revolt against Rome. The magics of the druids, their conversations with nature spirits. The fantastic creatures that lingered in the forests, the sea monsters that ruled the deep waters that surrounded the island, waters the same color as impenetrable fog, capable of confusing and losing even the most skilled navarch.

"I would never want anyone to threaten our land. I could never allow that."

Yet, with such sincere statements, Constantine had been able to earn his friendship, giving him several reasons to esteem the Romans.

"I think with Magnus Maximus we will not run into these problems. He is a great warrior."

"And so will we be!" blurted out Constantine snapping and pulling himself up to stand on the large branch.

He stared at Vortigern with fevered eyes.

"We have to swear it, my friend. We always wanted to be soldiers, remember? Remember? And then, as soon as we are old enough to hold arms, we will join the army so that no one can endanger all this!" he said excitedly, then spreading his arms wide to point to the green expanse in front of them, rising up to the green mountains of lush forests.

Vortigern stood in admiration, partly because of his friend's heartfelt speech, and partly because of the beauty and harmony of the nature surrounding them with its colors and scents.

"Whether barbarians or even Romans, no one should ever bring war and destruction to Britain. This is our world, and we will have to be the ones in the future to defend it from the pitfalls that are shaking the empire! So what do you say? Do you agree?"

The Briton could not help but smile. Constantine was capable of engaging anyone, with his small talk and seemingly cold but incredibly expressive eyes.

He was jovial but determined, easy to galvanize but also able to reason with studied precision.

A truly special guy.

And a sincere friend to love and trust blindly.

"I'm in!" he convinced himself to say Vortigern, standing up in turn and clutching his friend's arm.

Constantine smiled at him, his eyes shining with elation.

They then descended from the oak tree and headed for the mysterious monolithic complex, a legacy of that ancient and obscure world that both Vortigern the Briton and Constantine the Roman had decided on that spring day to choose as their own.

VII

Vocation

Lindum, September 386 AD.

Constantine was ecstatic. Already having accompanied his father to Lindum, an old town now used only as a military fortress, had thrown him into the castren world he had always dreamed of. Never, however, had he expected to find himself facing Magnus Maximus himself.

The man who had turned against the empire opening its doors to the barbarians, the military man who had come from the same land as the august Theodosius was there, seated before him in a small room hastily put back together as the leader of the British legions received some influential members of the Senate.

He took a closer look at him. He was sturdy, mighty with his broad shoulders, taurine neck, and muscular arms despite the purple he wore concealing his impressiveness. He wore his hair short, the color of straw, and had a large straight nose like that of the ancients. His forehead was prominent and furrowed by a few wrinkles, while his small eyes, almost set within their sockets, darted quickly. The square face emphasized the hardness proper to a man of arms.

He isolated himself completely from the speeches his father and Magnus were having, mostly pertaining to the economic performance of the major cities and the consensus of the population. Time after time, the thundering voice of what Ambrosius had repeatedly called Caesar had rallied him. There was no doubt about it: the lord of Britain was a most powerful man, revered by the legions, a true warrior whom he would have liked to ask so many questions.

But he was only there to keep his father company, so he decided, sadly, to remain silent.

Then, for a moment, he crossed the gaze of Magnus Maximus.

"Gods, Ambrosius, your son looks in every way like an ancient Roman! What is your name, boy?"

Constantine remained interdicted, his eyes wide. He turned back to his father, who with tight lips eloquently urged him not to make his interlocutor wait too long for an answer.

"My...my name is Flavius Claudius Constantine, my lord."

A good-natured smile appeared on the face of Magnus Maximus, who lifted his right hand from the armrest of his seat and made a gesture difficult for a young boy like him to understand.

He was, in truth, affably acknowledging the nobility of his progeny and the names they bore, august reminders of the past.

"And tell me, Ambrosius, how does your firstborn behave? Is he a true Roman in values as well?"

Ambrosius dissolved into a slightly forced smile, undoubtedly dictated by nervousness. His palms were sweaty.

"Of course, Caesar. Constantine diligently studies the classics of the greats of the past, and is educated in respect of the values that made the empire great."

"Sure, sure," did Magnus Maximus, stroking his freshly shaven face. Then he cast an intrigued glance at Constantine.

"Too bad, however, that the empire itself is bastardizing, letting vile barbarians sully its purest blood. That is why we have demanded justice by rising up in arms, as sons of one of the first regions that Rome conquered, a people always loyal to them."

Both Ambrose and Constantine nodded vigorously.

"What do you think, son? Did we act right?"

Constantine felt his legs soften and a lump clog his throat. He wanted to say a thousand things, to show that he was more mature than his twelve years old and capable of fine reasoning, but emotion and fear of saying some nonsense blocked him.

Magnus Maximus laughed. He had very white teeth.

"Don't be afraid. No one will send you to your death for your opinions. Not in this part of the empire, at least!" he urged him, bursting out laughing at his joke, followed by Ambrosius.

"I-I, I...agree. The empire must belong to the Romans. No people should be part of it for profit or necessity, as in the case of barbarians who are welcomed only to become servants or tradesmen with poor results. But rather they should be part of it only if they are really useful in fighting for the greatness of immortal Rome."

He bowed his head, hoping he had not gotten too out of line, but the clapping of Magnus's hands roused him.

He saw his father genuinely surprised by his elocution.

"Bravo Constantine! You honor your name with these words. Ambrosius, you really have a golden boy on your hands!"

"You honor me, Caesar," Ambrosius bellowed.

"But tell me, son. For the speaker you are despite your green age, what would you like to be when you grow up? Maybe a lawyer?"

Constantine widened his eyes.

What did he want to be when he grew up?

He actually had always known this. But his father and mother had always prevented him from doing so. Joining the army would have been a disgrace for a member of a senatorial family. Yet he felt that this was his calling. He certainly aspired to greatness, but he intended to get there as the ancients did back in the day, through a brilliant military career.

And the sympathy the most important man in Britannia seemed to have for him was too good an opportunity to pass up. He could not fail to come forward.

"Caesar, I...I..." he mumbled, freezing as he met his father's admonishing gaze. To hell with it, he told himself.

"I would like to be a legionnaire, Caesar!"

Magnus Maximus' eyes lit up.

"What fantastic news! We really need such proactive young people devoted to the original ideals of the empire!"

"Caesar, please...he's just a kid, he doesn't know what he's going to say..." intervened Ambrosius.

Magnus Maximus waved his right hand in the air.

"Not at all. The boy knows what he is saying. And I say, why not give young people, even noble ones, the opportunity to prove themselves not only before a preceptor or in administrative practice, but also by wielding arms? Are you forgetting that Rome conquered the world by fighting, Ambrosius?"

"No, no, not at all, my lord."

"So what! Constantine, if I'm not mistaken you are twelve years old, right?"

He couldn't believe it. Everything was going as he had hoped!

He nodded with a brilliant smile.

"I would say you need to study a little more," reflected Magnus, whose outgoing and strong-willed nature was making him like him more and more. He felt he was almost a friend. A very powerful friend.

"But in two years or so, you may already join the ranks. We'll turn a blind eye, given the spectacular family you're a part of," he smiled at him.

"Caesar, this is an incredible honor for me," murmured Constantine with tears in his eyes.

"Not a word more. Whenever you want, you can already go to the various camps and observe military techniques as the legionnaires practice. You can even serve as a volunteer servant if you wish. But let me give you something to remind you of this meeting of ours," Magnus said as he stood up and took some large scrolls from a dusty shelf.

Constantine took them from his large hands, and was stunned.

They were copies of Vegetius' De Rei Militari , the most famous treatise on warfare that existed, which was studied to death and respected in battle by the greatest generals.

A reading he had always wanted to undertake.

"It is right to stimulate bright and willing minds like yours. Today, I met a young friend from the empire," smiled Magnus Maximus at him, tousling his hair. "Ambrosius, make sure the boy reads this book well. That's all for now."