20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This practical book looks at the fundamental principles that underpin the process of architectural illustration: to represent architectural design and the built environment in a way that the general public can understand. Focusing particularly on watercolour, it explains the full process from site sketching to finished rendering. Case studies follow the process of an illustration, using demonstrations specially selected from the author's own work and profiles of leading practitioners. Illustrated with over 200 colour images, it is a unique guide to the work of the architectural illustrator and will be invaluable for artists, illustrators, architects, builders and planners.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

ARCHITECTURAL

ILLUSTRATION

PETER JARVIS

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2018 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Peter Jarvis 2018

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 404 9

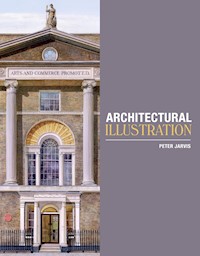

Front cover: The RSA building in John Adam Street is the home of The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. It was designed by the Adam brothers and completed in 1774 as part of their innovative Adelphi scheme. Several photographs were used as primary reference to piece together this view of the façade, which could not be seen in reality due to the narrow street. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 500 × 360mm.

Frontispiece: Southampton’s Bargate was built around 1180 and is constructed of stone and flint. It was the gateway to the walled city of Southampton and formed part of its fortifications. The dark washes applied to the underside of the archway establish the tonal range of the building and contrast against the view beyond. The figures help to give scale. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 350 × 430mm.

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1Context and Applications

Chapter 2Drawing Methods and Process

Chapter 3Composition

Chapter 4Using Colour

Chapter 5The Street View

Chapter 6The Aerial View

Chapter 7Topographical Illustration

Chapter 8Appraisal and Reflection

Glossary of Terms

Profile Artists

Useful Contacts

Further Reading

Index

Introduction

Adictionary definition of the word illustration is: ‘a picture, design, diagram, etc. used to decorate or explain something’. This book is about the illustration of buildings and the built environment and how buildings are seen in context. It’s not an instruction book on the use of digital methods, or any other medium, but it does cover some basics on a range of applications. It examines the subject primarily from the author’s standpoint as a traditional architectural illustrator, but also looks at the illustrator’s role in broad terms and how architectural design is presented in the public domain. It contains worked examples and step-by-steps, mainly hand-drawn by the author, in order to explain to the novice the fundamentals of the subject. Selected case studies and artists’ profiles are also included for interest to the more advanced practitioner.

Bishopsgate Institute was designed by Charles Harrison Townsend and opened in 1895 as a centre for culture and learning. This illustration shows the façade of the building as seen from the opposite side of Bishopsgate, but the naturally occurring vertical convergence has been corrected in Photoshop. Designed in the fashionable styles of the Arts and Crafts movement and the Art Nouveau style, this building has all the elegance of this period with filigree stonework and decorative twin roof turrets. Watercolour over pencil on 90lb Canson Montval Aquarelle NOT stretched watercolour paper at 580 × 320mm. (Courtesy of Luke Johnson.)

These days many illustrators work by combining traditional skills with computer skills, but it’s the role of drawing that remains the most important component in providing the foundation to a successful outcome. Drawing is about looking and observation, but it’s also about enquiry and investigation. Through observation one learns about the nature of a subject; how it works or what materials it is made from. The act of drawing on location, done over an hour or so in a particular place, will enhance other forms of studio-based applications. With regular practice, drawing and sketching skills help to improve an illustrator’s ability to create convincing and credible illustrations. Technical problems are often easier to solve through drawing and can be communicated without the hindrance of the written word. Many architects start out with freehand concept drawing as a means to exploring initial ideas. Such drawings can be referred to as the outcome of ‘self-commune’: engaging in a dialogue with oneself. There are many role-models to look to in this respect: the great architect Ted Cullinan is a master of the sketch and has produced many ‘draw and talk’ videos, and Sir Norman Foster is an enthusiastic advocate of this type of drawing. The late Hugh Casson famously sketched during his travels and published several books of his work done whilst visiting major British cities. More often than not, the role of the architectural illustrator will move back and forth from visualization to representation; from prediction to documentation, all of which can be described as illustration.

Approaches to drawing can be far-ranging and diverse in purpose and outcome. As a radical visionary, the late Zaha Hadid produced many drawings and paintings in which she explored the limits of architectural form. Much of this work was never realized in built-form but represented the potential of structural possibilities. She used perspective to communicate the dynamics of architecture and in doing so created dramatic results if, at times, somewhat inaccessible to the general public. Álvaro Siza, the great Portuguese architect, spoke about the different purposes of drawings: to generate ideas; to develop them; to communicate; or for simple pleasure. Many architects still talk about the pleasure of drawing and sketching as a way of exploring shape and form in design and this is still considered to be important alongside digital methods.

In architectural illustration it is crucial to have a knowledge of building materials and methods of construction. This can be very broad depending on the type and design of a building. Vernacular buildings can date from medieval times and rely on indigenous materials in their construction whereas modern city blocks are made from concrete, steel and glass. Familiarity with building terminology can help to avoid any misunderstandings between the illustrator and client; there is a glossary of terms at the back of this book. Many illustrators specialize in particular building types, often relating their style and method to its appropriate representation: a medieval hall house rendered as a computer generated image (CGI) might not lend itself to the medium as well as the use of traditional pen and ink or watercolour. The important skill here is in maintaining the consistency of style and technique within the illustration.

Photographic skills are also important and acquiring these has been simplified with the advent of digital technology. Many projects require the illustrator to superimpose proposed buildings into photographs of existing urban and natural landscapes. This process is often enhanced by using on-line maps and street views that have now become standard tools in the illustrator’s toolbox.

The term architectural illustration is a relatively modern one and has its roots in the topographical tradition of watercolour painting occurring at the start of the eighteenth century. Prior to this time early topographical drawings were often the work of surveyors and mapmakers who were familiar with the conventions of architectural drawing and perspective. During the late seventeenth century wealthy landowners would commission aerial views of their country homes from talented draughtsmen and artists. The topographical style was introduced to England in the drawings of Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677) and taken up by two Dutch draughtsmen, Jan Kip and Leonard Knyff, who produced many topographical views of British country houses and gardens in the form of engravings.

At this time the topographical watercolour was first and foremost a record of an actual place, its aesthetic value of secondary importance. By the mid-eighteenth century topographers were employed to record the traveller’s journey in the Grand Tour through France and Italy, which resulted in a proliferation of pen and ink wash drawings. Such drawings were reproduced and published in travel journals, art magazines and as prints.

The first artist to reveal the true aesthetic of the genre was Paul Sandby (1730–1809) who is often referred to as ‘the father of English watercolour’. Sandby and his brother, Thomas, greatly influenced both painting and architecture at this time. Paul Sandby was a founder member of the Royal Academy, established in 1768, and Thomas Sandby was its first Professor of Architecture. Paul Sandby was one of the pioneers in the use of watercolour for topographical scenes incorporating figure compositions in the foregrounds. Sandby’s work was very exacting and ‘draughtsman-like’ in execution, which typified the common approach to the medium at this time. Often described as ‘coloured-drawings’, they were finely drawn on watercolour paper in pencil with transparent washes overlaid. Although Sandby never visited Italy, his work was the first to reflect the new Romantic spirit developing in Europe and the interest in classical architecture. The Italian architect and visionary Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) was instrumental in this movement and many English architects including Robert Adam (1728–1792) and Sir William Chambers (1723–1796) went to Rome to meet him. The romantic and picturesque philosophy was here to stay. Through the medium of watercolour it was to capture the hearts and minds of the English people. Its essence was characterized by writers and theorists, most notably Uvedale Price (1774–1829) and Richard Payne Knight (1750–1824) who took its original relationship with the paintings of Claude and Poussin and developed a contemporary aesthetic idea. This notion of the ‘picturesque’ in art and architecture was a major factor in the way buildings and the landscape were portrayed at that time and has survived to this day.

Architectural drawing borrowed many of the qualities inherent in the picturesque aesthetic of the late eighteenth century. As a method of representation it was governed by the same influences that shaped the buildings themselves and architects strove to create atmospheric visualizations of their intended reality. In this ambition many compositional devices were used, such as a greater attention to landscape foreground and background, existing trees and buildings, entourage elements such as action poses in figures and horses, dogs and carriages as well as emphasis on colour, light and atmospheric conditions. The landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752–1818) used all these elements and more, in his now famous Red Books which he presented to his clients. These consisted of ‘before and after’ perspective drawings showing proposed new designs on a hinged flap attached to the drawing.

The new emphasis became focused on the enhancement of nature and its relationship with the built environment. Also, there was recognition of nationalistic differentiation between style and individuality. Natural landscape and atmosphere, peculiar to a particular place, became important in its representation and the demand from the travelling public was to encourage collectors of paintings and drawings from around the world.

A major effect of this new approach in architectural drawing was a rise in overall standards and the emergence of many artists who were largely untrained in the finer points of architecture. The most notable was J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) who, together with Thomas Girtin (1775–1802), was responsible for raising the profile of topographical painting to a fine art. Other noteworthy artists were Michael Angelo Rooker (1743–1801), John Varley (1778–1842) and later, John Ruskin (1819–1900) who was hugely influential in the promotion of the ‘Picturesque’ in watercolour painting which impacted on the topographical artist. Ruskin was a skilled draughtsman in his own right and his writings influenced how artists composed and presented both the natural and built environment in topographical painting.

Watercolour painting became an important skill to professional architects and surveyors in the representation of proposed architecture. Because of its ease of application, the medium of watercolour was widely adopted by draughtsmen in engineering and shipbuilding during the nineteenth century and many fine examples can be studied in both these areas. At this time a number of ‘how to’ books and guides were published giving advice on mixing colours in order to represent certain materials. The box given here shows examples of this and is typical of how materials were represented on measured orthographic drawings.

Colour coding in architectural drawing was in use by the mid-eighteenth century but not standardized. Different offices used a variation of colours to denote building materials, especially noticeable on sectioned elevations. The use of watercolour applications in both painting and draughtsmanship at this time perpetuated its popularity in England. It was a timely coincidence of the picturesque sensibility in art and architecture with the popularity of the medium, which was to have a significant effect on how architecture was to be represented in the future.

Unlike the topographical drawing, the perspective represented proposed architectural design and became a common means of showing buildings in a realistic setting. In fact the best perspectives were so convincing they were difficult to distinguish from topographical views. Of course this pleased the architects’ clients immensely and those with elite skill levels were in high demand.

Perspective drawings reached a height of achievement in the nineteenth century through the work of Joseph Michael Gandy (1771–1843) who worked exclusively on Sir John Soane’s architectural designs for eleven years. Most famously, the sublime quality of his aerial perspective showing Soane’s design for the Bank of England (1830) as a ruin, received critical acclaim. The architectural competition was, and still is, a common means in achieving design outcomes for public buildings. As a result of this there is a surplus of un-built design proposals stored in our national archives, where the perspective drawing survives as the only evidence of an architect’s vision.

The golden age of architectural drawing continued through the 1800s into the twentieth century with work from architectural artists and perspective draughtsmen such as Charles Robert Cockerell (1788–1863), Alfred Waterhouse RA (1830–1905), William Walcot (1874–1943) and Cyril Farey (1888–1954). The work of these and other skilled artists was in high demand and regularly exhibited in the Architecture Room of the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy. In fact, Farey was so popular that his work dominated the RA and the phrase ‘Fareyland’ was coined in this connection.

The picturesque sensibility in architectural drawing maintained a certain popularity throughout the nineteenth century and even alongside the Modern Movement of the 1930s and into the 1960s. It was fuelled by a variety of influences, not least the invention of photolithography in about 1868 when the first plate was published in The Building News. This brought about a great increase in the number of pen and ink drawings, a genre dominated by the work of Richard Norman Shaw (1831–1912), William Eden Nesfield (1835–1888) and Arthur Beresford Pite (1858–1934). Also with improvements in painting techniques generally, many drawings were reproduced using aquatint etching methods and these were regularly published in magazines such as Ackermann’s Repository and later in The Builder.

The new Gothic Revival style and the Arts and Crafts movement were also responsible for the continuation of picturesque qualities in drawing, although Ruskin and William Morris were concerned about the over-use of perspective drawing in their belief that good architecture was a matter of good building and not the method of its representation. The case for and against the use of perspective in the representation of proposed architecture raged on throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Architectural drawing methods began to embrace a variety of styles and techniques in order to produce eye-catching presentations that would stand out from the rest. One particular technique was referred to as ‘dazzle’, which was initially developed in pen and ink and later applied using other media. This is where atmospheric sky and landscape effects were used to add drama to a picture. Competency in architectural drawing and rendering has always ranged from the adequate to the inspired and artistic. Techniques in both traditional draughtsmanship and artistic representation were, and still are, a means to the creation of style. The technique of ‘dazzle’ in the hands of a competent draughtsman, demonstrated great command and skill, whereas by the less accomplished, it was over-used. This resulted in the method of representation becoming more important than the architecture itself.

Dazzle and similar techniques were used to develop a variety of drawing styles which, it could be argued, were a furtherance of the picturesque aesthetic. One of the most distinct drawing styles at this time can be seen in the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928). Mackintosh’s technique, much imitated, was the result of many influences, the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau being the most prominent.

The perspective drawing flourished from the early nineteenth century until the turn of the twentieth century. At this time controversy began to surround its preparation and use and the Royal Institute of British Architects decided that they should not be used in competitions and by the 1920s perspectives had all but disappeared from these events. Throughout these years of dispute, however, there continued to be a demand for perspectives especially for use in publications and exhibitions, the former being the most successful way of advertising an architect’s work. At about this time many newly qualified architects who displayed skills in drawing and rendering, began to specialize in this activity, marking the emergence of the full-time freelance illustrator.

With the increasing move towards specialization within the professions, the perspective artist became an established sub-profession of the architectural and building industry. Architects recognized this and were able to select a style of drawing and rendering to suit a particular project. As we move through the decades preceding the Second World War, opportunities arose for the architectural draughtsman who had the ability to visualize a design proposal in a pictorial manner. In the recession-hit 1930s, a recently trained architect who could draw and had the skill to visualize from plans could increase his chances of full-time employment.

At a time when the great public patrons of modern art included Shell, London Transport and the Post Office, the equivalent in modern architecture were of a much lower profile. The poster artists such as Edward McKnight Kauffer (1890–1954), Paul Nash (1889–1946) and Tom Eckersley (1914–1997) may have represented the new architecture in their work, but the public was still comparatively conservative in its response. Collaborations with painters was crucial in representing modern architecture in the same light and several associations between artist and architect were developed at this time. The Architectural Review was responsible for bringing together artists and writers of the day during the 1930s and ’40s. Articles by Nikolaus Pevsner, Robert Byron and John Betjeman were featured regularly in the magazine that saw Gordon Cullen (1914–1994) as assistant editor between 1946 and 1956. Cullen made a significant contribution to the content of The Architectural Review, both written and illustrated, which was partly responsible for the increase in his popular style of illustration and his inroads into book illustration and graphic work.

In the main, however, few architectural illustrators crossed the divide into publishing and book illustration. Some, like Hugh Casson (1910–1999), developed a painterly style of representation comparable with painters of the day and achieved recognition alongside the commercial artist for his loose watercolours. Most, however, relied upon sound draughtsmanship and stayed within the architectural and building industry for their work.

The early 1970s brought about the term ‘architectural illustration’ to describe this activity and the Society of Architectural and Industrial Illustrators was founded in 1975 as the first professional body to represent practitioners of the genre. This was later changed to the Society of Architectural Illustration (SAI) in order to reflect the subject matter as a result of its change to charity status in the mid-1990s. The establishment of the SAI was shortly followed by the American Society of Architectural Perspectivists (ASAP), now called the American Society of Architectural Illustrators (ASAI). As a result, many other societies across the world have since been formed.

The SAI represents a broad range of methods and media used by its members with specialisms including traditional and digital media, 2D and 3D illustration and animation, photography and model-making. Fields of work include reconstruction and heritage, publishing, advertising and the architectural design and building sectors.

Many artists and illustrators represent the built environment in their work, often using buildings as context or background as well as main subject matter. However, it’s the architectural illustrator who specializes in this genre, working in a variety of areas from creating house portraits to digital visualizations of proposed city schemes. In architectural design, illustrators are used at different stages of the process: before, during and after a building’s construction. At the initial design stage it is often the in-house architectural technician or visualizer who is employed to create presentation visuals working closely with the architects and designers with a freelancer brought in at a later stage.

Architectural illustration can be seen as a celebration of all things architectural and has a role in its representation from concept to built form. An architect’s initial idea sketches often deal with exploration and enquiry at the early stage of the design process and in the formulation of design intent; a sketch can contain the basis of communicating an idea to others and eventually lead to the realization of an architect’s vision. Once a building is completed it becomes the symbol and representation of this process and can be judged on its success or otherwise.

Even with the advent of the computer generated image (CGI) during the early 1990s, the client and public’s expectations of architectural illustration has changed very little. Its purpose is still to inform and expand the understanding of both proposed and existing architecture, albeit by ever more sophisticated means. Traditional rendering methods exist alongside digital means depending on the type and nature of a project. It is clear that there is a continuing requirement for conventional illustration training and a need for the illustrator to have a basic knowledge of ‘picture-making’, which is deemed just as relevant today as it was in the early twentieth century.

The activity of architectural illustration brings together a range of skills and knowledge within art and design, as summarized in the box. From sketching to SketchUp, and from pastel to pixels, the architectural illustrator engages in many areas of specialization and medium dependent upon the type, stage and process involved. Most illustrators develop a style that is commensurate with the type of commissioned work undertaken. Competence in freehand sketching, as well as more accurate drawing, is also fundamental to the illustrator’s skill set.

Architectural illustrators often have a qualification in architecture or interior design and specialize in making visuals. However, as a result of a research project undertaken by the author (Royal College of Art, 1996), it was discovered that illustrators have a breadth of backgrounds and training, including general illustration, fine art, graphic and exhibition (3D) design amongst others (one illustrator interviewed was an apprentice to the great sculptor Frank Dobson but turned to illustration afterwards).

Emerging from this rich heritage, today’s architectural illustrator fulfils an important role in communicating architectural design. Now in the twenty-first century, the time-honoured perspective view continues to play a central role in representing architectural design to an increasingly sophisticated audience. Alongside more general forms of illustration, architectural illustration plays an important role in representing aspects of the urban landscape.

MATERIALS COLOUR PALETTE

Cast iron

Payne’s Grey or Neutral Tint

Steel

Purple: mixture of Prussian Blue and Crimson Lake

Brass

Gamboge with a little Sienna or Red added

Copper

A mixture of Crimson Lake and Gamboge

Lead

Light Indian Ink with a little Indigo added

Brickwork

Crimson Lake and Burnt Sienna

Firebrick

Yellow and Vandyke Brown

Grey stones

Light Sepia, Burnt Sienna and Carmine

Soft woods

Pale tint of Sienna with a little Red added

Hard woods

As above but darker tint with greater proportion of Red

THE ARCHITECTURALILLUSTRATOR’S SKILL SET

Knowledge in:

•building materials and architectural history

•colour theory and rendering

•geometry and perspective

•website and on-line applications Skills in:

•traditional drawing and location sketching

•traditional and digital colour techniques and applications

•photography

•composition and design and layout

CHAPTER 1

Context and Applications

Having unrivalled powers of truth-telling it can also magnificently lie. It IS the honest architect’s most candid and Inconvenient friend: it is the dishonest architect’s most artful and convenient con-federate.

H.S. Goodhart-Rendel on the perspective drawing

Architectural illustrations are not just used in the architecture and building sector but also across a range of applications in the design, advertising and publishing industries. Commissions emanate from different sources and for a variety of reasons from historical reconstructions, through to the representation of existing buildings and the prediction of future built form, the appropriateness of each being central to its purpose. This chapter looks at the breadth of requirements and uses of illustration.

Detail of an aerial perspective view of a proposed housing scheme. The illustration gives a realistic representation of each building with indications of material type and colour as well as overall landscaping.

The commission

A commission can take a variety of forms and arise from a diverse range of sources, from an individual requesting a house portrait, to an international firm of architects who require a series of artist’s impressions. A new client may have found your website directly or through representation via an agent or membership of a professional body. Experienced or long-standing illustrators gain a large percentage of work though recommendation achieved through successful completion of prior commissions. Most illustrators will sign their work or have credits printed alongside the image which give name and contact details or website address. This is important and is the best way to acquire new commissions.

Most commissions arrive via an email message and the first step for the illustrator is to provide a quotation. In order to give a quotation the illustrator will need certain pieces of information which would normally include a set of architect’s drawings (sometimes referred to as a set of plans) if the project is a new build development, or photographs if the building is existing. Sometimes, information is less than forthcoming and it may be necessary to use Google Maps, or the equivalent, in order to identify the site, and Street View to see the building from street level. If the building or development is within reasonable travelling distance then there is nothing better than to make a site visit. Having an intimate knowledge of a project can save you much time and often means you can anticipate problems that may arise. It is often the case in the process of commissioning illustration, that the illustrator will spot an inconsistency on a drawing or identify a feature on-site that has been overlooked. It is usual to incorporate the expenses of a site visit into your quotation.

The client

Who, then, are those who commission architectural illustration? A client’s needs can range from an illustration in a magazine or journal to a complete advertising campaign; from a TV programme to a planning application. In the architectural and building sector, architectural illustration is generally accepted as a term that refers to a specialist service not normally available ‘in-house’. This service is often provided by a self-employed freelancer working as an independent or by a studio offering a range of styles. A client may be looking for a particular style or technique to fit in with a specific project or, in the case of a magazine editorial, a certain house style. Let us, then, look at potential clients and their needs.

The planning process

In England there are six stages in the planning application process for permission to build on land and illustrations can play an important role in achieving planning consent. For larger housing or mixed-use developments permission is considered through a committee, whereas for smaller and non-controversial schemes a planning officer will decide on the outcome. Either way, a visual of some kind, usually a perspective drawing, is often the best way to show what the scheme will look like once built. Sometimes it will be the planning committee, on receiving an application, who will request that a visual be prepared in order to clarify a particular building design or overall scheme. This is clearly an additional expense but can save time and money later on in the process. Planning officers and the make-up of committees vary in knowledge and experience and particularly in the ability to understand 2D plans and elevations. This is where the role of a perspective illustration comes in – by making the architects’ design intent accessible to all.

At other times an illustration may be needed to accompany an appeal when an application has been turned down and the developers need to give more visual information surrounding a particular project. The illustrator and designer often form a partnership in this process, the aim being to present a scheme in as convincing a way as possible in order to achieve planning approval. In this context the illustration is a means to an end. There’s a famous story about the design of a well-known cricket clubhouse which was presented using a perspective illustration drawn by the great architect and illustrator Cyril Farey. Farey portrayed the scheme with a game of cricket in progress and the committee spent all their time arguing about the way the cricket teams were placed on the field of play. This took the whole of the meeting and after a long argument at the end they approved the scheme without opposition – just like that!

Illustrations and visuals prepared to accompany a planning application can present many challenges, often determined by sensitive aspects relating to a site or scheme. Sometimes it may be as straightforward as blending new build materials and colour with local buildings in the immediate vicinity; at other times it could be the maintenance of existing trees protected under a preservation order or consideration for a historic landmark. This can be time consuming and expensive for the developer or client who would normally be instructing an architect or, in particularly difficult circumstances, a planning consultant in order to achieve a satisfactory result.

An illustrator may be brought in when the design is at an early concept stage requiring a ‘sketch’ approach and then later on when the design has been approved at outline planning. A concept sketch may be concerned with a building’s ‘massing’ in order to give the client an idea of the overall scheme, or just an indication of how a new building will look alongside adjacent buildings or landscape features. (When dealing with listed buildings this is always of prime concern.) A more finished illustration would normally be commissioned when the design is finalized and for promotion and selling purposes. Achieving planning consent is rarely a straightforward business and for good reasons: after all, most of us live and work in and around urban environments as well as in rural towns and villages so we would expect the process to involve consultation, particularly with local groups and other interested parties such as the Environment Agency. For example, the presence of protected species or wildlife habitats would necessitate some form of provision and this may need to be represented in illustrations of a scheme. The most common example of this is the presence of bats or newts, which can delay planning approval for more than a year giving time for observation as to whether a habitat is still in use.

Generally speaking, perspective illustrations are the most useful form of visualization and can be understood by the majority of people. However, they are also the most subjective and this means that it is the illustrator’s responsibility to portray a building and its setting honestly. This can be done purely through drawing or by superimposing photographs onto a background. Through image-manipulation software such as Photoshop this can be an effective method of communication and a way of explaining aspects concerning scale and proportion, particularly when blending new buildings with existing.

Advertising and marketing

Art directors regularly commission illustration and can work from positions within large companies or advertising agencies. Advertising campaigns are often well funded and commissions can be very lucrative for the illustrator. The downside is that work can be all-consuming and extend over a considerable time, taking precedent over smaller commissions. Large building companies and developers will employ advertising agencies to promote and market new properties soon to come on to the housing market, and this forms a significant source of work for the architectural illustrator.

As with planning applications, mentioned earlier, whatever the issues involved in this type of project, illustrative material needs to represent a proposed scheme with honesty. This is particularly important within the architectural design and building industry. During the construction boom of the late 1980s there was a proliferation in the demand for the ‘artist’s impressions’ and artistic licence abounded. There were limited restrictions over the way new buildings were represented which led to a plethora of over-elaborate and misleading information. In 1991 legislation was brought in to control the description of property through advertising and sales literature which resulted in the Property Misdescriptions Act. Prior to this time protection was provided under the Trade Descriptions Act 1968 and the Misrepresentations Act 1976. A major change under the new Act was that control was extended to cover those other than estate agents, which included solicitors, house-builders and developers. Much of the new Act was based on the Estate Agents Act 1979 and covers all forms of publication including text, pictures, plans, advertising of all kinds and anything said in conversation. It is now an offence to publish misleading or false statements and it is important to include a disclaimer to cover any liability. As a result there was a general feeling of nervousness about the enthusiasm that some illustrators and their clients had shown in artistic representation of buildings, and the industry has since been more concerned with monitoring the appearance of illustrations. Nevertheless, controversy still remains over the visualization of proposed architectural design even with digital methods which are often indistinguishable from an actual photograph.

The way a building design is presented in the public domain has always been a sensitive issue. An artist’s impression, in the right hands, can be a form of visualization that allows the general public to make sense of a proposed development but in the wrong hands it can be misleading. A good example of this was the controversy surrounding the redevelopment of Paternoster Square next to St Paul’s Cathedral in London, which took 10 years and 3 schemes to result in its final approval. The perspectives produced for one proposal were highly criticized as dishonest after publication in the media. One illustration showed a view looking across the square from an impossible viewpoint positioned inside an existing building.

With large schemes the best way to show how a design looks is to commission a traditional card model. These days the model would be created using a digital file and outputting to a laser cutter, with the assembly done by hand. The advantage of the model is that it can be viewed from an infinite number of positions, if somewhat reliant on a certain amount of imagination in doing so. In reality, particularly with large schemes, successful communication relies on several forms of illustration and use of media combining traditional and digital 3D, still and animated representations.

Like any other product, buildings are designed to a budget and for a purpose. In housing this will range from a one-off architect-designed dwelling to a large residential development. Architects and developers often specialize in building uses, covering commercial, leisure, healthcare, education, heritage and conservation. After planning consent, and before work starts on-site, it’s important to promote and advertise a new scheme. Sometimes this is purely for selling purposes in the private housing sector but it may also be to attract investment or to promote a business opportunity. In housing, advertising is aimed at a specific demographic, for example first-time buyers or the retired, and this will influence the composition and features included within an illustration. Entourage elements are worth spending time and practice on to complete the overall convincing nature of a composition. If the inclusion of cars is necessary as part of a busy urban scene, then it’s important that they are up to date – the same goes when including people, ensuring they are dressed in contemporary clothing without looking like they have just left the catwalk! Entourage elements can help to suggest activity relating to a particular building use or place. Many illustrators build up a collection of relevant images to include in a composition, such as people, cars, trees, animals, garden and street furniture, all of which add to the credibility of an illustration.

Advertising work means that the illustrations could be used in a variety of ways from television to magazines and the press, so it’s important that the work is scanned as a high resolution file at around 600dpi, which will normally fulfil most applications. The largest reproduction would be used on hoardings or large-scale advertising street signboards; anything less than 600dpi will produce a pixelated image at this size.

Publishing

The book publisher will be looking to match an illustrator’s style and ability with a particular book title. If the subject is sixteenth-century vernacular buildings then a hand-drawn style may be the answer. Should the title be concerned with the design of contemporary office blocks then a digital rendered technique may be the most appropriate. Book illustration work is often commissioned with good notice of the publication date allowing the illustrator time to research, plan and prepare artwork. The author and illustrator of a children’s book are often one and the same, or at the very least have a close working partnership. The most likely titles requiring architectural subject matter here would come under non-fiction subjects. Commissioned illustration could be for cover or dust jacket only, or for contents as well depending on subject matter and budget. There is a plethora of titles relating to architectural design, many of which are profusely illustrated. Such books often contain explanatory drawings including cutaway views, elevations and plans, aerial and street view perspectives and interiors showing room layouts and furnishings. These illustrations are often annotated and captioned to provide information about the design and historical styles and developments over the centuries. This means that the illustrator would need to follow the editor’s instructions carefully as well as to engage in research into design aspects and theories.

In book illustration the size and layout of the artwork is often dictated, depending on whether there is a series’ house style or if the book is a one-off and the designer is brought in as a freelance, similar to the illustrator’s contract. In this case the illustrator is normally supplied with a page layout or at the very least a page grid showing the text and image roughly positioned as a guide to an illustration’s shape and format. A designer may require illustrations to be produced as artwork to a specific size, particularly if there is to be a large number of images in the book. This could be twice or three times up on the finished printed size so that the artworks are all consistent throughout the book. Sometimes the style of artworks is set by the editor if there are several illustrators involved, again for the sake of consistency as in the case of an encyclopaedia or travel guide. The position where an illustration sits on a page layout is important for the illustrator to know for several reasons. Will the illustration bleed off the top or side of the page? Will it be positioned across the gutter? How much space will be allowed for any annotations and captions? All of these questions will dictate the overall shape and design of an illustration and how it sits on the page.

Generally speaking, publishing commissions are less well-paid than advertising work but can extend over longer periods of time. This means that it can be easier to work around a book project alongside other commissions. Also, book editors are normally specialists within their subject areas and experienced in commissioning freelance illustration. They will often have spent time unearthing reference material that the illustrator can use, thus cutting down the time spent on research.

Editorial

Working for magazines and journals can be fast paced with short deadlines, depending on how often a title is published. Newspapers are even faster and deadlines for commissioned illustration can often require turn-rounds within 24 hours. The illustration style needed here would have to be economical in terms of output. Monthly magazines are a rich source of commissioned artwork for many illustrators with art editors able to plan several weeks ahead. This gives the illustrator time to spend on research and preparation prior to working on final artwork. The relationship that an illustrator builds with an editor is of utmost importance and is often one that lasts for many years. As with book publishing you are in the hands of the editor who will have publication deadlines that cannot be extended, so the illustrator must be prepared for the allnighter from time to time. The author once spent most of Christmas and Boxing Day completing a commission for Good Housekeeping magazine with a deadline before the New Year! However, with judicious workload planning this can usually be kept down to a minimum.

Organizing your workload

Workload organization is crucial to an illustrator’s skill set and accepting too much work at one time can only end in tears. Having a balance of different types of work can be an advantage and offer opportunities for a regular workload at times when there are peaks and troughs. With experience, structuring work so that there is continuity between different stages of projects running concurrently can be possible without getting overly stressed. Most projects can be broken down into the following stages: initial briefing; site visit and/or research; draft composition for client approval; and the finished artwork. Working on more than one job at any one time needs careful organization and planning, depending on deadlines and the complexity and size of project. Large projects may necessitate a considerable amount of reference material including architects’ plans, photographs and drawings. This means that picking up and changing from one job to another can be quite an upheaval. This is less of an issue when working digitally where all the reference material is stored on the computer, but even here the mental transition in redirecting one’s concentration across several projects should not be underestimated. When possible, aim to start and complete one project at a time.

CASE STUDY 1

Planning application: Swan Cottage, Alresford, Hampshire

Context

Architect’s site plan drawn at a scale of 1:200 showing the existing plot with proposed changes and additional extensions to the cottage. (Images 1–7 courtesy of Chris Carter RIBA.)

A listed building with recent extension on a large plot including a stream and lake within a wooded area of mature trees and shrubs was acquired with planning permission to improve, refurbish and extend the existing accommodation. The architect’s brief was to provide a design proposal which was sensitive to the age of the property as well as the location. The property is located on a mature plot which has been somewhat neglected in recent years. The gardens were mainly laid to grass and incorporated large mature trees, hedging and boundary shrubs with extensive bamboo planting, all of which was to be cleared and improved although changes to the overall landscaping was to be kept to a minimum.

Illustration brief

Ground floor plan drawn to a scale of 1:100 showing proposed extension to the existing cottage.

The brief was to prepare two watercolours showing the cottage and grounds with the new build extension blended within the existing walling and planting. The cottage had a roof covering of clay tiles and it was agreed to replace this with a reed thatch which was confirmed as the original roofing material using photographic evidence. The timber-framed extension was added quite recently and designed by the renowned classical architect Robert Adam and was to be replaced by extending the original flint-faced wall and ‘disguising’ a new timber single-story building. Finally there was to be a timber bridge spanning the narrow stream to the lake at the side of the cottage. The whole emphasis was to be on the vernacular qualities of the building and blending new with old. The architect agreed with his client that, in order to show these changes to the planning officer, there would be a need for two perspective views, one from the lake showing the rear gardens and cottage, and the second of the front aspect from the road.

Orthographics of each elevation drawn at 1:100 showing proposed changes and extension to the existing cottage.

Orthographic drawings of a proposed new link bridge at a scale of 1:100.

Process

Site photograph of existing south aspect from the rear of the garden.

One-point perspective drawing showing the extension to the left of the cottage, the new thatched roof on the cottage and link bridge to the right-hand side.

At the time of preparing the artworks the architect’s design drawings were at an early concept stage, drawn by hand and not for public scrutiny. This meant that it was necessary to interpret these in the spirit of the architect’s verbal briefing when we met on site. As mentioned earlier the emphasis was to be on the rustic qualities of the dwelling and gardens (in other words, plenty of ivy and wild flower meadows) but without taking artistic liberties. So the first task was to assess the 50 or so photographs taken on the site visit and make a decision on the best viewpoints. Starting on the rear view it was straightforward to match the position where the selected photograph was taken and mark this point on the site layout drawing. This way the photograph could be used as a basis and the drawing of the extension to the cottage, new thatched roof and the new bridge superimposed. When taking site photographs it’s advisable to set the focal length to around 50mm which roughly equates to the eye’s normal cone of vision without peripheral distortion. This way when setting up a perspective drawing from the site plan to a similar angle of view, it will blend with the photograph. The same process was adopted for the street view of the front using photographs taken from the road. On this one, due to a rise in the camber of the road, it was possible to establish an eye-level that was slightly raised which was taken into account when setting up the drawing of the extension to the cottage.

Once scanned, both pencil drafts were emailed to the client and received approval to progress to finished colour. Comments received regarding the rear garden view included creating the impression of a wild flower meadow, and for the street view to ‘ghost’ the new extension through the boundary hedging. At the time of writing the architect and his client are still awaiting planning approval.

Finished colour view from the garden based on the photograph but incorporating a wider field of view in order to take in the bridge and glass fronted extension. Watercolour over pencil on 140lb Arches 226 × 436mm.

Site photograph of existing entrance from the road showing the existing round building which was to be replaced.

Pencil draft showing a perspective view of the proposed replacement extension and revised entrance. Part of the extension is shown ‘ghosted’ through the hedge to show its position and level as seen from the lane.

Finished colour view from the lane showing the remodelled entrance drive and hedging. Watercolour over pencil on 140lb Arches 241 × 362mm.

CASE STUDY 2

Advertising brochure: listed Georgian town house, Chichester

Context

A Grade II listed Georgian townhouse in Chichester scheduled for reallocation from an apartment and offices to its original residential use, requiring extensive refurbishment. An emphasis was to be placed on the provision of a day room offering views of the gardens which had been well maintained and stocked with mature trees and planting. The house can be accessed from the large garden and garages to the rear of the property and the developers were keen to express the potential that the property could afford through on-line and brochure advertising.

Illustration brief