Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

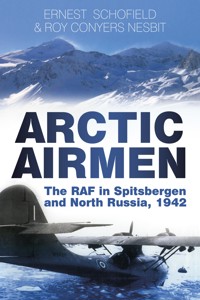

In 1942 a Catalina crew of 210 Squadron, based at Sullom Voe in the Shetlands, was selected to carry out a series of highly secret operations, including a flight to the North Pole. The sorties were associated with a Norwegian expedition from Britain to Spitsbergen, to deny the use of the territory to the enemy. The flights made by the crew were frequently over twenty-four hours in length and reached the limits of human endurance, in conditions of extreme cold. Later, the squadron was detached to North Russia, to provide cover for the convoys taking vital supplies to the Allies on the Eastern Front. The navigator of the crew, Ernest Schofield, retained logs of most of these sorties. Together with other survivors of the crew, accounts from German sources and research carried out by Roy Conyers Nesbit, he recreated these little-known events, in detailed and accurate narrative that ends in tragedy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Tim

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the help given to us, when researching the material for this book, by officials and staff at the following organisations:

Aeroplane Monthly, International Publishing Corp., Sutton.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Maidenhead.

Forsvarsmuseet, Oslo.

General Dynamics, Convair Division, California.

Imperial War Museum, Lambeth.

Ministry of Defence, Air Historical Branch, Holborn.

Ministry of Defence, Naval Historical Branch, Fulham.

Public Record Office, Kew.

Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon.

Royal Geographical Society, Kensington Gore.

Royal Greenwich Observatory, Herstmonceaux.

Royal Norwegian Embassy, Pall Mall.

Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge.

Our thanks are also due to those who generously contributed their detailed recollections of the events related in this book:

Sir Alexander R. Glen, KBE, DSC.

Flight Lieutenant Ronald Martin, RAFVR.

Squadron Leader Reginald W. Witherick, RAFVR.

Flight Lieutenant George W. Adamson, RAFVR.

We should like to express our gratitude to Mrs Jean Podlipny and Mr Brian Healy for contributing their recollections of the early life of their brother, Flight Lieutenant Dennis E. Healy, DSO.

For the accounts of the German weather airmen in the Arctic, we have drawn on the research and writing carried out by Herr Franz Selinger, and we are very grateful to him and his colleagues for authorising us to make use of records and photographs.

For translation from Norwegian and German records, we have benefited from the assistance kindly given by Mrs I. Moorcraft and Mr N. Wajsmel, and by the staff of Forsvarsmuseet in Oslo.

Mr Harry R. Moyle was most generous in letting us have the results of his researches into the fates of the Hampdens of 144 Squadron during their flights to North Russia.

We should also like to thank Mr Gordon Railton and Mr Michael H. Nesbit for assistance with copying and improving old photographs, and Mr Peter Nesbit for designing the cover.

Crown copyright material in the Public Record Office is reproduced by permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Finally, we should like to express our gratitude to families and friends for their tolerance and help while we were engaged on writing this book, in a period when unexpected problems caused long delays.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Sir Alexander Glen, KBE, DSC

Authors’ Note

1

Reluctant Volunteer

2

Sullom Voe

3

Spitsbergen

4

On Our Own

5

Operation Fritham

6

Catalina ‘P for Peter’

7

Turning Point

8

Operation Gearbox

9

Consolidation

10

The North Pole

11

Operation Orator

12

Tragedy

Epilogue

Appendices

I

Correspondence with Headquarters, Coastal Command

II

The Flight Made by Flight Lieutenant G.G. Potier

III

Polar Navigation

IV

Decorations

Bibliography and Sources

Copyright

List of Illustrations

Flight Lieutenant D.E. Healy (B. Healy)

Pilot Officer E. Schofield (E. Schofield)

Pilot Officer Ronald Martin (R. Martin)

Flight Lieutenant Healy’s crew (E. Schofield)

Catalina flying boat (Aeroplane Monthly)

Amphibian PB-Y Catalina (General Dynamics – Convair Division)

Twin Vickers machine guns in cupola (Imperial War Museum)

Single Browning machine gun in cupola (Imperial War Museum)

Sergeant T.R. Thomas at radio desk (Imperial War Museum)

Bunk compartment in Catalina (Imperial War Museum)

Pilot Officer R. Martin in navigator’s compartment (Imperial War Museum)

He 111 and Ju 52 being loaded (W. Schwerdtfeger via F. Selinger)

He 111 at Longyearbyen (W. Schwerdtfeger via F. Selinger)

Longyearbyen and Advent Bay (F. Selinger)

‘Bansö’ near Longyearbyen (//. Moll via F. Selinger)

Ice edge (E. Schofield)

Drift ice (E. Schofield)

Longyearbyen (Sir Alexander Glen)

Longyearbyen (Dr Teich via F. Selinger)

Ju 88A at Banak (Dr Pabst via F. Selinger)

He 111 at ‘Bansö’ (Dr Teich via F. Selinger)

Kröte weather station (Dr Pabst via F. Selinger)

Kröte weather station (W. Glenz via F. Selinger)

Longyearbyen (R. Martin)

Green Harbour Fjord (Sir Alexander Glen)

Icebreaker Isbjørn (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Icebreaker Isbjørn and sealer Selis (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Bombs exploding on Isbjørn and Selis (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Isbjørn sinking (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Selis sinking (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Survivors scattering across ice (Dr Daser via F. Selinger)

Model of Catalina ‘P for Peter’ (R. Martin)

He 111 damaged at Advent Bay (H. Zeissler via F. Selinger)

He 111 damaged at Advent Bay (F. Selinger)

He 111 in ice hole (Sir Alexander Glen)

Wireless aerials at Hjorthamn (H. Pilchmair via F. Selinger)

Cape Heer (E. Schofield)

Survivors waving from hut (Sir Alexander Glen)

Western coastline of Spitsbergen (E. Schofield)

Horn Sound (E. Schofield)

Paddling ashore in dinghy (R. Martin)

Fending office floes (Sir Alexander Glen)

Cape Heer (E. Schofield)

Cape Borthen (E. Schofield)

Cape Linné (E.Schofield)

Lieutenant Commander A.R. Glen and Flight Lieutenant D.E. Healy (R. Martin)

Lieutenant Commander A.R. Glen (E. Schofield)

Wing Commander H.B. Johnson (E. Schofield)

Cape Brewster (Sir Alexander Glen)

Catalina at Reykjavik (R.C. Nesbit)

Ju 88 under gunfire (Sir Alexander Glen)

Wreckage of Ju 88 in 1984 (F. Selinger)

Captain E. Ullring (Sir Alexander Glen)

Dr Etienne and Leutnant Schütze (Dr Teich via F. Selinger)

Drift ice (Sir Alexander Glen)

Wreckage of Hampden (R. Kugler via F. Selinger)

Flying Officer R.W. Witherick (R.W. Witherick)

Pilot Officer G.W. Adamson (G. W. Adamson)

Maps and Diagrams

Operational Area from Sullom Voe

Spitsbergen

Icefjord in Spitsbergen

Operations in North Russia

Polar Zenithal Equidistant Chart

‘GH A’ to ‘G’ Correction Chart

Foreword

by Sir Alexander Glen, KBE, DSC

For many centuries, the Arctic Seas had known only peace. True, skirmishes between Dutch and English whalers troubled the Spitsbergen bays in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but these were limited local affairs and strategic war was unknown.

The Second World War brought abrupt change. The sinking of Hood by Bismarck in the Denmark Strait was the first act in the opening of a new and bitter theatre of operations. Then came the build-up of German naval and air power in northern Norway. When the German onslaught on Soviet Russia took momentum, it might have seemed that the gate was closed on any western attempt to supply her new ally by the Northern Seas.

The Allies took a little time to recognise the new strategic situation. Information on the Arctic Seas was scant enough and almost non-existent about the sea ice, particularly in the narrow and vulnerable channels between North Cape of Norway and Spitsbergen. Flying had been restricted to some four exploratory flights. In any case, the RAF had no aircraft capable of reaching the higher latitudes until it began to receive delivery of the Catalina flying boats. Most important of all, the fortunes of war in 1941 and 1942 were such that survival more than occupied the minds of most. There was little to encourage long-term gambles, or indeed anything beyond the problems of the day.

A few highly placed officers thought differently. The Assistant Chief of Naval Staff, Rear Admiral E.J.P. Brind, and the Director of Operations Division (Home), Captain J.A.S. Eccles, were at one with the director of Naval Intelligence, Rear Admiral J.H. Godfrey, in assessing the appalling problems the northern sea route would pose. In Coastal Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip Joubert, ably backed by an outstanding Senior Air Staff Officer, Air Vice Marshal G.B.A. Baker, had already perceived the contribution that the new ‘very long range’ Catalinas might make.

If the Falklands campaign was fought at long range, just as extreme were the air and naval operations of 1942/3 over the Arctic Sea. The most critical sector passed through enemy air space and. indeed, what could have been enemy-dominated sea space. The channels between North Cape, Norway, Bear Island and Spitsbergen were especially critical and Spitsbergen itself was a pivotal point.

Allied policy accordingly was to deprive the enemy of the use of Spitsbergen provided this could be done by a small mobile force with minimal demand on the war effort elsewhere. Germany’s interest, as this book shows, was significantly different. Logistically they felt stretched far enough in northern Norway itself, and their compelling need in Spitsbergen was for weather stations. It was perhaps hesitancy on the part of the German High Command, shown especially in their failure to deploy effectively their capital ships concentrated in northern Norway, that was to make it possible for the Allies to maintain the northern sea route to Russia, despite appallingly heavy losses in June 1942.

The Allies’ solution was a small land force of some eighty Norwegians, mostly ex-miners from Spitsbergen, hardy, experienced in polar survival, skilled ski runners, men who regarded the Arctic as their home. How they turned initial disaster into outstanding success is part of the story told in this book.

The other and central part is how one Catalina of 210 Squadron, commanded by Flight Lieutenant D.E. Healy, DSO, and navigated by Flight Lieutenant E. Schofield, DFC, made this possible. In the course of three 24-hour flights in seven days in May 1942, they made contact with the survivors of the original force, re-armed them, then evacuated their wounded, and finally provided the communication link which enabled survival to be turned into attack.

In January 1987, forty-five years later, Ernest Schofield, Ronald Martin (the second pilot) and I attended the opening in northern Norway of the Norwegian Defence Museum’s exhibition of these events. It included the German activities in the Arctic, including the achievements of the Luftwaffe weather squadrons, as well as those of the Allies. It is good that there should be displayed throughout Norway such a record of how a tiny Norwegian garrison held Spitsbergen, even surviving bombardment of the heavy ships of the German Navy, including Tirpitz. It is also important historically that the contribution made by ‘Tim’ Healy and his crew, which was vital to the Allied recovery as shown in this narrative, is suitably included in these exhibitions.

The consequences of these events, however, are both greater and longer-lasting than any of us would have thought forty-five years ago. Not only did Spitsbergen remain a free Norwegian territory throughout the war years, it remains so today. Spitsbergen’s pivotal position has a new and contemporary significance in the context of the massive concentration of Soviet power in Murmansk.

Authors’ Note

Although the narrative of this book is written in the first person by one author, Ernest Schofield, it is in fact a joint work with another author, Roy Conyers Nesbit.

In October 1984, Ernest Schofield attended a talk given by Air Chief Marshal Sir Lewis Hodges, KCB, CBE, DSO, DFC. During a discussion afterwards, Ernest Schofield mentioned that he had flown on a number of special flights to Spitsbergen and North Russia, and still had in his possession several navigation logs written in the air while engaged on this Arctic flying.

Sir Lewis Hodges was interested enough to approach Air Commodore Henry Probert, MBE, the head of the Air Historical Branch of the Ministry of Defence. In turn, Air Commodore Probert suggested to Roy Conyers Nesbit that he should take a look at this material, particularly since it included an account of the first attempt by the RAF to fly to the North Pole.

Ernest Schofield and Roy Conyers Nesbit combined forces to research the background to these flights, at the Air Historical and Naval Historical Branches of the MoD, the Imperial War Museum, the Public Record Office, the Royal Geographical Society, the Scott Polar Institute and many other places. They also obtained from sources in Germany the Luftwaffe side of this story. Above all, they traced several of the participants in this dramatic conflict.

Thus, the navigation logs provided an accurate basis, but only a starting point, for this little-known story.

1

Reluctant Volunteer

Many Royal Air Force (RAF) aircrews were required to fly on hazardous missions during the war. Some were aimed at specific and important targets with precise objectives, such flights normally being part of a squadron effort in which many aircrews took part. Occasionally, however, some tasks had to be carried out as lone operations, with little advance preparation. I was a member of an aircrew required to undertake such a series of flights, one of which probably ranks as among the most unusual of the war - a reconnaissance flight to the North Pole.

At a time when advances in technology have brought precision to air navigation and airlines make regular scheduled flights at high latitudes, such a task may now seem fairly inconsequential. However, for a squadron aircrew to be singled out and expected to tackle such a project in the circumstances of 1942 was unprecedented, especially since we ourselves were required to solve all the problems that were entailed.

The polar flight was associated with a Norwegian expedition from Britain to Spitsbergen. The original intention was that Coastal Command would play only an ancillary role in the operation. In the event, however, our aircrew became directly involved and other squadron aircrews also had to take part. These flights, and the impact that they made on the operation, constitute the main events in this narrative.

Immediately after the adventures in Spitsbergen and the attempt at the polar flight, a detachment of the squadron moved to North Russia to take part in an operation to protect convoys taking military supplies to our Allies on the Eastern Front. These Russian sorties provided further experience of Arctic flying and led to the tragedy that befell our aircrew.

All these northern patrols were long flights, many of them over twenty-four hours in duration, crossing the apparently endless expanses of Arctic seas in flying conditions that tested human endurance to the limit. In themselves, they are worthy of being placed on record. But of even greater significance is the recognition deserved by the men who made them possible.

The polar flight and the Spitsbergen sorties were exceptional, as was the captain chosen to undertake them. It was my privilege to be the navigator of his crew. This resulted partly from selection, but it could also be attributed to some accidents of fate. In fact, my position in the aircrew was somewhat anomalous since, although I volunteered for flying duties, it was expediency which prompted me rather than a wish to see action in the air.

I was born in 1916 of Yorkshire parents, Benjamin and Alice Schofield, in the moorland town of Penistone. Four years later, my family moved to Derby where I followed my elder brother to the municipal secondary school, which was later renamed Bemrose School. My strongest subject in the lower school was mathematics, but by the time I entered the sixth form geography occupied first place. This brought a scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge, where I changed my preference once again and read economics, gaining an honours degree in due course.

Cambridge provided an environment where hard work could be combined with a very enjoyable life style. Two hours rowing on the Cam every afternoon improved physical fitness. This offset the strain of grappling with the theories of John Maynard Keynes, the most eminent economist of the time. Listening to such great masters enlarged my appreciation of what seemed to be the unlimited capacity of some human intellects. We learned how to tackle the unknown and gained confidence in our ability to achieve results from logical analysis. The subject matter was to have little bearing on wartime activities, but it is probable that these studies engendered an attitude of mind which helped me in subsequent events.

It was extremely difficult to find a job in the inter-war years of depression. My solution was to stay on for a fourth year at Cambridge, reading history, until I was old enough to take the competitive entrance examinations for the Civil Service. I took up my first post in January 1939, in the Department of Inland Revenue. This turned out to be an occupation which, on the outbreak of war eight months later, carried ‘reservation’ from military service. This was no embarrassment to me. I was sure that I possessed no latent military talent, and I would have been quite content to make my contribution to the war effort as a civilian.

The rapid advance of the Wehrmacht across Europe changed my status. ‘Dereservation’ of my occupation brought the option of waiting for conscription or volunteering for the service of my choice. The Army did not appeal at all, for it carried the stigma of trench warfare in my estimation. The Royal Navy was also a non-starter, for I suffered from sea-sickness. On the other hand, the aircrew branch of the RAF seemed to offer some attractive features. New recruits could not be expected to know much about flying, so there would have to be a good training scheme. This might bring into play the only skill I had to offer the armed services: the ability to study and pass examinations. It also occurred to me that an aircrew was a small unit in which each member might exert some control over his own destiny. Another factor was the influence of the recruitment posters. They had a somewhat civilised look about them, for even the humblest airman wore a collar and tie. Perhaps there would be less unnecessary and irksome discipline.

There was no point in applying to train as a pilot. I had never owned a car or a motor bike and the internal combustion engine was an uninteresting mystery to me. I knew nothing about navigation either, but it might call for the sort of calculations that had appealed to me in the past. Thus, on 9 July 1940, I joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR), seeking to become an air observer, which was the title given to the navigator in the recruitment literature.

After three days of examinations, interviews and inoculations, the Board Chairman at Cardington Reception Centre announced my fate. I was to be trained as a pilot! The Chairman seemed to expect an enthusiastic response. Instead, I tried to point out that there had been a mistake. The reaction was short and specific. There were to be no questions and no explanations. I was now in the Royal Air Force.

‘Right turn, quick march!’

Once I had been selected for pilot training, everything happened at speed. The first step was to Babbacombe, to be kitted out. From there, we recruits moved a few miles along the coast to No. 5 Initial Training Wing at Torquay. We received elementary training in ground subjects, while physical training was high on the list of priorities. We ate well and put on healthy tissue.

From Torquay, our group of trainees were posted to an Elementary Flying Training School at Cambridge, where we began flying in Tiger Moths. The pressure was on and the rejection rate was high. One had to learn quickly or fall by the wayside, sometimes for reasons outside our control. Bad weather restricted the total number of hours available to the course, so that fewer trainees could reach the required number. Although my prowess in ground subjects gave cause for praise, my skill in the air did not develop sufficiently quickly. I was one of the last to be ‘scrubbed’. It so happened that the casualty rate among that group of trainees was extremely high during the next two years, so that I can now look back with mixed feelings on that week of bad weather in the middle of October 1940.

So many ex-pupil pilots were queuing up at Babbacombe for training as air observers that a temporary ban was imposed on such remustering, but the Chief Instructor at Cambridge listened sympathetically to my pleas and turned a blind eye to the regulations. Fortunately, no one at Babbacombe raised any objections when I arrived, so that at last the RAF and I were not at odds about how I might best help the war effort.

Suspension from pilot training also brought my first opportunity to apply for leave. Only forty-eight hours were granted but that was enough for me; I married my wife Hattie on 19 October 1940. The honeymoon had to be delayed for a fortnight, but then Hattie joined me at the hotel in Babbacombe where I was billeted; this was another example of the war effort being helped by the turning of an official blind eye.

There were four stages in the training of air observers: Navigation School, Bombing and Gunnery School, Operation Training Unit, and finally training on an operational squadron. I was one of a group of trainees who were posted to No. 6 Air Observer Navigation School at Staverton, near Gloucester, on 9 December 1940. Classroom instruction was provided by former members of the Merchant Navy. They did their best, but to someone accustomed to university and Civil Service standards of instruction, there seemed to be scope for improvement. We were taught rule-of-thumb methods, without much reference to underlying principles. I had an innate objection to doing anything that someone told me was the correct method, without adequate explanation. The long and dark evenings gave me plenty of opportunity for private study to supplement the formal lectures. I delved quite deeply into most aspects of the course, to the amazement and even the disgust of those trainees who preferred the attractions of the canteen. When the course ended on 29 March 1941, I felt that I had acquired a good understanding of the principles of air navigation, as well as associated subjects such as maps and charts, meteorology, signalling and air photography. But I had little confidence in my ability to navigate an aircraft, even in daylight. Our training flights, in Avro Ansons, had usually ended over the required township, but I attributed that accuracy more to the pilot’s knowledge of the terrain than to our navigational skill. We had become more accomplished at map-reading than dead-reckoning navigation. Most of my fellow-trainees went to Bomber Command, where proficiency in map-reading must have been particularly important at that stage of the war.

To my dismay, I learnt something else at Staverton. Even before take-off, the smell of an Avro Anson made me feel sick. Soon after we took off, that feeling became a reality, all too often. There was a handle beside the pilot’s seat, which we had to wind at great speed to raise or lower the undercarriage. When it was my turn to carry out that chore, the effect on my stomach was usually disastrous. The RAF turned out to have a disadvantage comparable to that of the Royal Navy, with the saving grace that aircraft returned to base after shorter time intervals. It was possible that operational aircraft did not have the same pungent smell; I could only hope for the best.

The next stage of our training was No. 10 Bombing and Gunnery School, at Dumfries in Scotland. The Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley Mark IIs, from which we practised air gunnery, were too sedate to upset even my sensitive stomach, but the same could not be said of the Fairey Battles, which were used for bomb aiming. I could only claim credit for containing myself until we returned to the runway. I never dropped bombs in an operational squadron and only fired a machine gun on two occasions, so that little need be said about the course itself. An entry in my flying log book records my performance as ‘Above average in theoretical knowledge. Requires more air firing practice.’ My bomb aiming could have been described as abysmally poor, but some of the other trainees seemed little better.

The conclusion of this course, on 23 May 1941, brought the award of the observer’s brevet and promotion, either to the rank of sergeant or commissioning as a pilot officer. There were thirty trainees on the course, nine of whom had been to public school and one, myself, to university. We expected about a third of us to become commissioned officers. In those days, schooling had a very strong bearing on selection. I was delighted to be the first called for interview by the squadron leader responsible for making the recommendations. However, I was very surprised to be greeted with a brusque accusation on entering his room.

‘You’re not fit to be a navigator!’ ‘Scandalous.’ ‘Outrageous.’ ‘It should be a court martial offence.’

These were just a few of the expressions which punctuated the ensuing tirade. I was too bewildered to guess what misdemeanour I had committed. When in trouble, say nothing. So I waited in silence, hoping for divine intervention.

Eventually, a chance remark from the adjutant, who had been standing behind the squadron leader, revealed the cause of the furore. It transpired that my medical record card, completed in Cardington three days after I had joined the RAF, designated that I was medically unfit to be an air observer. The card had been filed away and not re-examined until I was considered for a commission. A lot of effort and expense had been wasted in training me for a job that I was officially unfit to perform.

A lull in the storm enabled me to mention that King’s Regulations forbade any airman from knowing the contents of his own medical record, and that up to then I had no knowledge of any medical defect. A heavy silence fell on the room, followed by smiles and sweet reasonableness.

‘You’ve made a good point … it would seem to let you off the hook … unfortunately, it puts someone else right on it. … we’ll have to do something about it, shan’t we?’

We had suddenly been united by a common purpose, and my respect for my commanding officer took a sharp upward turn. It was explained that the fault lay with my eyesight. I had known for a long time that I had an astigmatism in one eye, but presumed that this was so slight as to be of no significance. It was not bad enough to debar me as a pilot but it brought me just below the standard required for an air observer, who needed especially good eyesight to pick out landfalls and bomb targets. At last, my selection for training as a pilot rather than as an air observer could be explained.

The other members of the course were posted to Bomber Command Operational Training Units. I stayed behind, while the wheels of the RAF administration slowly turned. A long series of medical examinations then followed, at increasing levels of authority: bombing and gunnery school, station, group, command, and finally Adastral House in London, where a senior eye specialist held court. Yes, my eyesight was below the required standard, but only just. The standard itself was currently under review and might soon be amended. It would be a pity to waste all that training, at a time when qualified aircrew were so urgently needed. If I was still keen to fly …

The medical officer took out his pen, deleted the letters ‘un’, and stamped and initialled the amendment. The record then read ‘Fit pilot and fit air observer’. He said he hoped I wouldn’t mind if he added a rider that it would be as well not to send me on night bomber raids, where a slight defect in the bomb aimer’s vision might detract from the effectiveness of the mission. I had no objection whatsoever.

Back I went to Dumfries, to be commissioned and to await posting. That came a fortnight later. It was to No. 4 Coastal Command Operational Training Unit, at Invergordon on the Cromarty Firth, in Scotland. It was a base for flying boats which, in those days, many airmen regarded as the aristocrats of the air. This type of operational flying certainly appealed to me as a budding air navigator.

There was a further reason why other trainees might have envied my good fortune. The statistics for aircrew losses (as shown later in a table sent to the Air Member for Personnel on 16 November 1942) showed that aircrew on Catalina flying boats had a 77.16 per cent chance of surviving a tour of operational flying. This was the highest survival rate in all types of aircraft. Comparable figures for the other trainees leaving Dumfries were 44 per cent for those posted to heavy bomber squadrons and only 25.2 per cent on light bomber squadrons. Needless to say, the figures for two tours were correspondingly far less.

Before leaving Dumfries, on 7 July 1941, I was given a certified copy of Form 657, stating that I was medically classified to serve as both a pilot and an air observer. It was thought that such a certificate might help allay concern if other members of the crew saw me wearing spectacles. It was never necessary for me to produce the form, since only one eye was needed for drift measurements while binoculars could be used quite effectively as a spyglass. However, I have kept the document as a memento of the kindness of fate, for my guardian angel must have been working diligently on my behalf.

I found that I was one of ten air observers posted to Invergordon for operational training. We trained on two types of flying boat, an old Short Singapore and Saunders-Roe Lerwicks. The other nine trainees were Canadians and Australians, whose previous courses had included astro navigation. A special astro course could not be laid on just for me. I was given the appropriate manual, with instructions to read it up myself and to refer to the others if I needed any help. I required assistance only in the practical use of sextants. Most of my astro observations were taken from the ground, and I found that I regularly fixed the position of Invergordon to the east or west of its correct longitude. I soon realised that it was my watch which was inadequate. It was essential to have a service wristwatch which recorded Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) precisely; every second of timing error resulted in misplacing Invergordon by one eighth of a mile.

Quite obviously, astro navigation is only possible when the ‘heavenly body’ (the sun, moon, planet or star) is not obscured by cloud. In our later Arctic flying, this was rarely the case. Even when the sun was visible, it was usually only for very short intervals. Nevertheless, a good understanding was essential for the tasks that lay ahead. At Invergordon, I had to transpose most of my reading into three-dimensional diagrams to clarify understanding. Perhaps it is sufficient here to say that I took the opportunity to delve much more deeply into the subject than would have been the case on a normal astro course.

After two months at Invergordon, on 9 September 1941, I was posted to 210 Squadron at Oban, on the west coast of Scotland. This was a flying boat squadron which had been equipped with Short Sunderlands since June 1938 but had begun to receive Consolidated Catalinas during April 1941. It was building up to its complement of flying crews while awaiting the arrival of more Catalinas from the USA. Usually, only four aircraft were operational at any one time when I joined the squadron, and these were manned by experienced crews. Thus, there was little opportunity to continue air training during the first weeks. Occasionally, a beginner such as myself could be given the chance to fly as second navigator and watch an experienced man practising his craft.

My mentor at this stage was Pilot Officer George Buckle, a navigator who was approaching the end of his operational tour. We flew on a few transit flights which were uneventful. I learnt how to measure drift accurately over the sea, and developed the art of estimating wind velocity by studying the surface of the water. The stronger the wind, the larger the white caps thrown back from the crests of the waves and the clearer the lane markings made by the wind on the surface of the sea, showing the wind direction. Alert observation of the sea and the sky were basic requirements for good dead-reckoning navigation in low-flying aircraft of Coastal Command.

My last flight as a squadron trainee was on 23 December 1941, under the captaincy of Flight Lieutenant D.C. McKinley, DFC. This was the pilot who later captained the modified Lancaster bomber ‘Aries’ which flew over the North Pole in May 1945.1 My flying log was then endorsed ‘qualified for the squadron role’. Three months had gone by since I had joined the squadron, and my contribution to its activities had been very limited indeed.

This was followed, during January 1942, by three short flights as first navigator to Flight Lieutenant C.M. Owen. However, the following month brought a change in our circumstances. The whole squadron, now fully equipped, moved base to Sullom Voe in the Shetlands.

I had expected to make the journey as a passenger with one of the established crews. Instead, I was told the good news that I was to fly as navigator with a captain who had been recently promoted, Flight Lieutenant D.E. ‘Tim’ Healy. He already had the reputation of a captain to be respected and was fast becoming one of the squadron’s personalities. Moreover, he was still looking for a full-time navigator. I had already learned something of his likeable character from his second pilot, Pilot Officer Ronald Martin, who praised the compassion with which he had sympathised with the widow of an officer who had lost his life.

The transit flight from Oban to Sullom Voe, on 14 February 1942, was to herald the most eventful period of my service in the RAF. In itself, it was an inauspicious beginning, but it was from such small accidents of fate in war that one’s future was sometimes determined. The two men I had the good fortune to join on that day are so prominent in the events of this narrative that more thorough introduction should be made.

Dennis Edward Healy was born on 26 August 1915 in Suez, the second son of Henry Francis and Maud Elizabeth Healy. His father was of Irish parentage and worked for the Eastern Telegraph company, now part of Cable and Wireless, while his mother was a Canadian of Welsh stock. Eventually, another boy and a girl were born in this family.

Henry Healy’s job took him and his family overseas and back to England for several periods. In 1916, he worked in the Red Sea area, while his wife and family lived in Southsea. In 1921 the whole family transferred to Capetown, returning to England in 1924. Then he moved to Malta and, after a while, the family joined him there in Valetta. By now, Dennis was aged 11 and, like his elder brother Brian, was an adventurous and lively boy who was keen on all forms of sport. This was at a period when Britain was still a very strong naval power, and the boys could watch the battle fleet sail in and out of Valetta harbour on manoeuvres. They were also choristers at St Paul’s Cathedral in Valetta.

When Henry Healy was appointed to a cable station on the Greek island of Syra, about 80 miles from Athens, a decision had to be taken about the boys’ education. They were sent to a small public school at Abingdon, where there was a strong Protestant and classical tradition. Dennis entered into the school activities with great gusto. He rowed, played rugger and hockey, was good at athletics, joined the photographic society and became a member of the OTC.

In 1931 this education came to a sudden end, when Henry Healy was made redundant. Dennis had matriculated by now, but jobs were hard to find. He worked for a while as a parcel wrapper in the despatch department of Debenhams store, but a better opportunity came when, in 1932, he joined the Gas Light and Coke Company as a staff pupil. There he began his training as a fitter’s mate, attending to gas installations from the humblest tenement in London to the splendour of Buckingham Palace. He attended night school and obtained qualifications which led him upwards to the company’s secretarial and financial departments. By the outbreak of war, he was an assistant service supervisor in the company’s Westminster office, covering an area throughout central London.

In addition to an intense application to his career, Dennis led an active social life. He enjoyed music and dancing, and became a member of a group which performed concerts at charity shows. He also joined the company’s amateur dramatic society, where he once took the leading role in a play. This interest in acting led to a meeting with Madeline Rushworth-Lund, a young lady who also enjoyed this activity. They married and went to live in a small bungalow in Stanmore, near his parents. Here their first child, Michael, was born.

Like thousands of other patriotic young men, Dennis was affected by the international tensions and the rumours of war in the late 1930s. He joined the pre-war RAFVR, as a part-time trainee pilot. His initial training was at Fairoaks in Surrey, and he was at the annual camp when war was declared. The next few months were spent at Initial Training Wing at Cambridge, but in April 1940 he was posted to No. 20 Service Flying Training School at Cranbourne in southern Rhodesia, to continue his flying training. He was commissioned in November 1940 and moved on to George on the southern coast of South Africa for a course in general reconnaissance, the normal prelude to the entry into Coastal Command.

He arrived back home in the late spring of 1941 for a short reunion with his wife and young son, both of whom he adored, for he had a passionate belief in the happiness of family life. Then followed a posting to the OTU at Invergordon, for conversion to flying boats.

In the summer of 1941, Dennis Healy arrived at Oban to join 210 Squadron, at the time when they were flying with Catalinas. His first flight was on 16 July as second pilot to Flight Lieutenant P.R. Hatfield, a Catalina pilot who, on 26 May 1941, relocated the battleship Bismarck after it had eluded the pursuing British warships, thus assisting its interception and destruction. Healy flew regularly with Hatfield for the next four months, engaged primarily on anti-submarine sweeps and convoy escort duties. On one occasion they took a group of special passengers to Archangel in North Russia. They stopped at Invergordon to top up fuel tanks and then had to land at Deer Sound in the Orkneys to remedy an oil fault. They then continued the 17½-hour journey round the North Cape of Norway to Archangel. The passengers continued to Moscow, a personal contact between senior officers of the Allied Forces on the Western and Eastern Fronts. The return journey was nine days later.

Flight Lieutenant Dennis Edward Healy, DSO.

Pilot Officer Ernest Schofield, DFC.

Pilot Officer Ronald Martin.

I saw little of Dennis Healy during my first few months in the squadron, for he lived outside the officers’ mess with his wife Madeline. But I knew of his reputation as both a second pilot and, later, a captain. He was tall, lithe, and good-looking, with a very alert manner. He normally wore battledress in readiness to be called out to his flying boat, and the badge on his peaked cap was green from salt spray, as befitted a ‘boat man’. In the mess itself, his manner was light-hearted and smiling, and he was very popular as well as highly respected. Like all those with the Irish name Healy in the RAF, he was nicknamed ‘Tim’ and that is how we all knew him.

Tim Healy’s breezy and gregarious nature concealed a man of steely resolve, however. He took the business of flying very seriously indeed. In fact he was a perfectionist, preparing for his sorties with extreme care and, so far as humanly possible, leaving nothing to chance. Every tiny item received his attention, to the point where he could be considered over-meticulous. For instance, he always insisted on leaving one blade of each propeller pointing precisely vertically. But no one in his crew objected to his attention to detail. Instead, we tried to live up to it. It was, after all, reassuring for our own safety to fly with such a highly competent captain.

The second pilot, Pilot Officer Ronald Martin, was born in 1918 in South Shields, where his father was a merchant dealing in yeast and other provisions. He attended the local high school and left at the age of 16 after he had obtained the Cambridge school certificate. Academic studies did not appeal to him; he was far happier on the sports field, playing cricket, rugger or tennis, or taking part in athletics.

His ambition was to join the RAF as a trainee pilot and then to move on to Imperial Airways. Aviation was his main interest, and he studied the theory of flight to the extent of making practical flying models. He was certainly not interested in spending his working life in an office. But parental influence was such that he became articled to an accountant for four years, and entered his father’s business in 1938.

Nevertheless, his interest in aviation could not be curbed and he joined the Civil Air Guard Movement. The purpose of this organisation was to train pilots, at the very reasonable rate of 5s (25p) an hour, and thereby create a reserve of pilots in the event of war. By the end of August 1939, when private flying was brought to a halt, he had managed to complete several hours of flying with the Newcastle Aero Club at Woolsington airfield, now Newcastle Airport.

The 21 age group had registered for national service in June 1939, and Ronald Martin had been earmarked for service in the RAF. His call-up papers arrived in June 1940. The first few weeks were spent in kitting out and drill at Padgate reception centre. From there, he moved to No. 5 Initial Training Wing at Torquay, as a pilot under training. By coincidence, I was there at the same time, but we do not remember meeting each other.

Unlike myself, Leading Aircraftman Ronald Martin proved to be a most successful pupil pilot. He was posted to No. 6 EFTS at Sywell, near Northampton, where he went solo after only five and a half hours’ dual instruction. It was normal for trainees to move from Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) to Service Flying Training School (SFTS), but the need for operational pilots was so acute that a few trainees of above average ability were sent direct to No. 13 OTU at Bicester, in Oxfordshire, to convert to twin-engined Bristol Blenheims. However, this experiment proved disastrous and there were a number of fatal accidents. Ronald Martin and his surviving colleagues were fed back into the normal pattern of training.

A short refresher course on Tiger Moths at No. 10 EFTS at Weston-super-Mare was followed by standard twin-engined training, on Airspeed Oxfords at No. 14 SFTS at Cranfield in Bedfordshire. Here he was awarded his wings and commissioned as a pilot officer.

He had hoped to be posted to a night-fighter OTU but fate and the authorities decreed otherwise. It is a fact that the steadier pilots of high ability were destined for long-range work in Coastal Command. He was posted to No. 3 School of General Reconnaissance at Squires Gate, near Liverpool. Here he flew Blackburn Bothas, considered by many pilots to be one of the most difficult and dangerous aircraft in the wartime RAF. However, his performance earned praise and he passed out in first place in his course. From here, he was posted to No. 4 OTU at Invergordon. He converted on to flying boats, first Saunders-Roe Londons and then Consolidated Catalinas.

Flight Lieutenant Healy’s crew in February 1942. Seated left to right: Pilot Officer R. Martin, Flight Lieutenant D.E. Healy, Pilot Officer E. Schofield. Standing left to right: Sergeant T.R. Thomas, Sergeant H.V. Watson, Aircraftman D. Baird, Sergeant B. Webster, Sergeant G.V. Kingett, Sergeant J.E. Campbell, Sergeant K. Jones. Seven of these men later flew in Catalina ‘P for Peter’.

His final posting was to 210 Squadron at Oban but, once again, he required further training, particularly since he had not yet qualified for night flying on Catalinas. This was completed on the squadron.

During this long period of training, Ronald Martin’s interests had not been wholly confined to flying. In June 1941 he had married his fiancée, Margaret, whom he had known since shortly after leaving school. The young couple were able to live for a while outside the RAF station at Oban. On Christmas Day 1941, Ronald and Margaret attended a party at the Great Western Hotel. Margaret noticed a tall, slim and debonair RAF officer leaning against the piano. He had a glass of beer in his hand and was singing enthusiastically and tunefully. Impressed by his appearance and manner, Margaret asked who he was. Her husband proudly explained that she was admiring his new captain, Tim Healy, and that they would shortly be flying operationally. Introductions followed, together with the opportunity to meet Tim’s wife, Madeline.

These were the two pilots whom I was fortunate enough to join on 14 February 1942, on that short transit flight in a Catalina from Oban to Sullom Voe. The two men addressed each other as ‘Tim’ and ‘Ronnie’, and I was known as ‘Scho’. The ‘Tim-Ronnie-Scho’ relationship started immediately, as the three officers in the crew. It continued for the next six months of arduous flying, mainly over the Arctic waters to the north of the Shetlands.

We were equally fortunate in the remainder of our crew, all of whom were first-class men. Four of these already knew and respected our captain. These were the wireless operator/gunners Sergeant G.V. Kingett and Sergeant T.R. Thomas, and the flight engineer/gunners Sergeant E.D. Gilbertson and Aircraftman D. Baird. Sergeant J.E. Campbell joined the crew as rigger/gunner, and also proved to be a good cook. The post of third wireless operator/gunner was at first filled by Sergeant H.V. Watson and later by Sergeant J.L. Maffre. In time, Sergeant Gilbertson moved on and was replaced by Sergeant B. Webster, then by Sergeant E.C. Horton, and finally by Sergeant R.M. Smith.