30,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

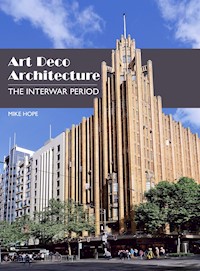

Art Deco burst upon the world for a brief but unforgettable existence during the 1920s and 1930s. It embraced new media, such as the cinema and radio, as well as new forms of transport and the associated buildings, and above all brought a sense of luxury, fun and escapism to the world during some of the hardest times. Art Deco Architecture - The Inter War Period examines the sources and origins of the style from before the First World War. It offers an in-depth exploration of the origins, inspirations and political backdrop behind this popular style. Lavishly illustrated with images taken especially for the book, topics covered include: a worldwide examination of the spread and usage of Art Deco; short biographical essays on architects and architectural practices; an in-depth examination of French architects and their output from this period; an introduction to stunning and little-known buildings from around the world and finally, the importance of World Fairs and Expositions in the spread of Art Deco.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Art DecoArchitecture

THE INTERWAR PERIOD

Art DecoArchitecture

THE INTERWAR PERIOD

MIKE HOPE

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Mike Hope 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 600 5

Frontispiece: Detail of relief sculpture around main entrance of Brooklyn Public Library. New York, 1940.

Contents

Acknowledgements }

Preface }

Introduction }

Chapter 1 } Post-First World War France – From the start of a new architectural vocabulary and style to Classical Modernism

Chapter 2 } America – The creation of a new architectural style for a new superpower

Chapter 3 } Britain – A stylistic conundrum

Chapter 4 } Britain – Key architects and buildings

Chapter 5 } Art Deco around the world

Chapter 6 } World Fairs and Exhibitions: Their influence as incubators and disseminators of a new architectural language and decorative style

Conclusion }

References }

Bibliography }

Index }

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my grateful thanks to the many colleagues and people over the last thirty years who have helped develop and shape my passion for Art Deco. During the last four years the tours which I have run through Travel Editions, looking at the Art Deco architecture of London, Liverpool, Lille, Antwerp, Hamburg, Stockholm, Helsinki, Riga, Lisbon, Valencia, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, Madison and Phoenix, have allowed me the opportunity to gain a real overview and insight. Most recently, over the last three years, the discussions and walks around Chicago with Marshall Jacobson which have put so much into perspective and context.

To Ann Howe for providing support and expertise in the seemingly endless process of making sense out of my content, structure and the endless proofing. Alongside this has been her readiness to drive me around Yorkshire, the North East and the North West of England and the East Midlands to visit and photograph buildings.

To Patrizia Sargent for likewise patiently driving me around West and East Sussex.

For the supply of specific photographs for the book from Ann Howe, Steve Hartnell, Tom Hiemstra, Annet Konnings-van Loenhout and Terry Lambregts.

And last but by no means least, my partner Terry Lambregts who has not only provided constant support at home but also used her knowledge of her own country as we criss-crossed the Netherlands. Without her, such architectural delights as Zonnestraal, Radio Katwijk and the service station near Nijmegen would have possibly remained unknown and certainly not visited by me. Hers too was the foresight to give me a present of a subscription to the Dutch language magazine, Art Deco, which has been for four years a constant source of inspiration and information. She has accompanied me on many expeditions in the UK and Europe, sharing the driving and the excitement of seeing so many remarkable buildings. Thank you for your patience and understanding.

Mike Hope

Preface

Art Deco architecture is not an architecture of personalities, of star architects. It is an architecture of the buildings themselves…1

Patricia Bayer

Whilst travelling around the UK, Europe and America over the last ten years I have been struck by the sheer amount of architecture from the early years of the twentieth century which remains sometimes well kept, but normally forgotten and more often than not neglected and at the mercy of speculative development. In many towns it is almost impossible to find out even the most basic of knowledge, such as a date or an architect’s name.

This highlights a deeper problem: aside from the superstar buildings of all types, sizes and uses, which appear with a monotonous regularity in books and magazines, there is a larger pool of buildings which deserve much greater acknowledgement and protection from destruction and unsympathetic restoration and re-use. The sadness which permeates the site and few scant reminders of that glorious factory that was the Firestone Building, on the Great West Road at Brentford, in West London, merely accentuates the precarious nature of so many of the buildings which survive from the 1920s and 30s. For many of such a size, it is hard to see successful alternative uses. On the other hand, the utterly magnificent Hoover building in Perrivale has found a new existence as the home of a Tesco superstore, with the front offices most recently being converted into sixty-five apartments.

What has changed, however, during the last twenty-five years since Patricia Bayer’s book, is that many of the major architectural practices (especially in the United States) have received a lot of attention and research. The result of this has been a stream of magnificent monographs which have gone a long way to redressing the balance with regard to the identification of localized Art Deco architectural styles.

That this book has a proportionately larger section on Britain than on America and France is quite deliberate. Whilst being international in its outlook and coverage it is firmly based in Britain, which can claim a wide range of outstanding examples from many of the styles.

This book not only celebrates the well-known, but attempts to champion and publicize the less well-known and off-the-beaten track examples of this multifaceted architectural period. One of the positive benefits of the internet and social media is the joy with which people have discovered and then shared with the rest of the world hidden architectural gems in their neighbourhoods and countries. This explosion of images and information has merely highlighted how much has still to be done to research and in many cases champion the survival of these buildings.

Mike Hope

Marnhull, Dorset, February 2019

Introduction

Art Deco architecture was an architecture of ornament, geometry, energy, retrospection, optimism, colour, texture, light and at times even symbolism; many times this vibrant, decorative interwar architectural style was marked by a lively, altogether unexpected interaction and contrasting of two or more of these elements…2

Patricia Bayer

Decorative tile panel from a former Co-op shop, Arnold, Nottingham.

I have often been asked for a definition for Art Deco. To stop and pause to consider what on the face of it should be a relatively straightforward response leads to a welter of names, descriptions and no clear or succinct answer.

The Birth of a New Movement

So what led to the development, spread and diversity of the style? Like all styles, it has no specific start date. Whilst Art Nouveau may be readily seen as the previous style that Art Deco would supplant, it has to be remembered that Art Nouveau was, as with Art Deco, a style that metamorphosed into a series of national and regional variations.

A number of key architects stood out as producing work that acted as a precursor to Art Deco – in America, Frank Lloyd Wright would produce a string of buildings that certainly crossed boundaries, as did Eliel Saarinen in Finland and America. In this category of course such architects as Mackintosh and Joseph Hoffmann feature prominently and thus bring in the Vienna Secessionist Movement and the Glasgow School, alongside the National Romanticism of Finland and Sweden.

ALTERNATIVE NAMES FOR ART DECO

In my research and travels I have come across literally dozens of names, which include: odeon Style; Style Liberty; Moderne; Le Style Moderne; Jazz Moderne; Zig-Zag Moderne; British Moderne; Nautical Moderne; Modern Ship Style; Pacqueboat Style; ocean Liner Style; White Modern; Futurist Art Deco; Streamline Beaux Arts; Streamline Moderne; PWA Moderne; PWA/WPA Moderne; Federal Moderne; Depression Moderne; Classical Moderne; Classical Modernism; Modernist Classical; Chicago School; Czech Architectural Cubism; Italian Futurism; Prairie School; Atmospheric Theatre; Med Deco; The Amsterdam School; Nieuwe Zakelijkheid; Mayan Revival; Japanese Secession; Spanish Pueblo Style; Pueblo Deco; Finnish National Romanticism; Neo-Gothic; Neo-Byzantine; Neo-Egyptian; Spanish Mission; Modernist Movement; Modern; International School; European International Style; Wiener Werkstatte; The New objectivity; Neue Sachlichkeit; New Sobriety; Neues Bauen (New Building); Free Classicism; Stripped Neo-Classicism; Deco Free Classicism; Stripped Classicism; Transitional Modern; vogue Regency.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Unity Temple, detail of exterior facade. 1905. Oak Park, Illinois, USA.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock House, detail of exterior facade.1917. Los Angeles, California.

Eliel Saarinen, Helsinki Railway Station, Finland, detail of tower. 1919.

Eliel Saarinen, Helsinki Railway Station, Finland, detail of exterior facade. 1919.

Willem Marinus Dudok, Hilversum Town Hall, The Netherlands. 1931.

H.P. Berlage Gemeente Museum, The Hague, The Netherlands, detail of clock face. 1935.

Fritz Hoger, Chilehaus Building, Hamburg, Germany. 1924.

In the Netherlands, architects such as Willem Dudok and H.P. Berlage and the Amsterdam School would develop Expressionist brick architecture, as did Fritz Hoger in Germany.

In France it was the seminal work of Auguste Perret that would lead the way internationally from the highly organic, fluid, linear approach of Art Nouveau decoration towards a more restrained yet highly floral and still naturalistic/geometric decorative approach. This would of course become one of the key elements in the development of an international Art Deco architectural vocabulary.

Defining Art Deco

The term Art Deco has become a catch-all nomenclature covering a period which most people would take to be between 1925 and 1939, but with many specialists now looking at the years 1910 – 1940. But there is no real route map through all of the developments taking place during this period. The speed with which styles (often driven by political and geo-political ambitions) developed and were then replaced mirrored the rapidly changing social, economic and political changes that gripped the world during the interwar years. Certainly contemporary theorists, practitioners and critics alike had no recourse to an all-encompassing label such as Art Deco.

Auguste Perret, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Paris. 1911–1913.

Having just mentioned those dates, it is important to note that Art Deco has its first flowering in buildings from before the First World War (in Paris, the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 1910) and most certainly was being used during the Second World War and beyond. As this hybrid of styles with national and regional varieties spread around the globe, so too did the names for this bright, brash and new trend, as listed above. One interesting note is that in certain parts of the USA during this period, Art Deco buildings were being referred to as ‘Modern Classic’.

If confusion is evident, then that confusion is something that is neither new nor settled. It is something that is constantly shifting. It is interesting that in the seminal 1979 Arts Council Catalogue and Exhibition, ‘The Thirties’, Art and Deco are two words that are absent. Yet by July 2017 it is used as a catch-all phrase to cover many different styles within the period. A classic example of this confusion is in an article describing the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill:

‘This was the high summer of Art Deco, and although the winning design, by Erich Mendelsohn, a German Jewish refugee, and Serge Chermayeff, whose parents had fled Tsarist pogroms, echoes the Modernist movement of which they were exponents, the beautiful curves and lines of the design, the sleek metal framed windows and the luminous white colour speak loudly of Art Deco. Indeed, it is reminiscent of one of London’s finest buildings of that genre, the mansion block at 59–63 Prince’s Gate in South Kensington, built by Adie, Button and Partners in 1935 – the same year as the Pavilion.’

Mendelsohn and Chermayeff, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea. 1935. Exterior view.

Mendelsohn and Chermayeff, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea. 1935. Interior view of staircase.

The author goes on to say:

‘Pevsner’s volume on East Sussex specifies what gives Mendelsohn and Chermayeff’s design its distinction and charm compared with the more regular Art Deco such as Prince’s Gate… Is it the best Art Deco building in Britain? Despite the greatness of the Hoover Factory, Broadcasting House and Prince’s Gate, yes: I think it probably is.’ 3

There in those few paragraphs, the mixture of styles and hesitancy as to just what specifically makes up Art Deco architecture is there for all to see and reflects a more generalized and widespread use and attachment of this architectural label in the second and third decades of the twenty-first century.

A Global Trend

By 1918, the world was undergoing a series of fundamental shifts both politically and economically. Geographical boundaries had moved and a number of factors acted as catalysts for change. The old order was in a state of flux and everywhere a new generation of artists, architects and designers were seeking to create something different, not prompted by any one single political or economic event. Rather it was a combination of events which would create the necessary climate for a new style, and more importantly its introduction and widespread usage.

Gerrit Rietveld, The Schroder House, Utrecht, The Netherlands. 1923.

Walter Gropius, Main Building, the Bauhaus, Dessau, Germany. 1926.

In France, almost from the outset, the fledgling architectural movement that had grown in Paris and North Eastern France was surrounded by and competing with the Modernist approach of Robert Mallet-Stevens and Le Corbusier; from The Netherlands, the influence of De Stijl, the Amsterdam School and the work of Willem Dudok; from Germany the work of the Bauhaus; from Russia the Vkhutemas School in Moscow and the Constructivist movement; from Scandinavia the development from National Romanticism to Scandinavian Neo Classicism.

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Villa Cavroix, Croix, Roubaix, France. 1932.

These movements would soon be added to by the arrival from across the Atlantic of the American forms of Art Deco.

A whole range of factors and influences fuelled the development and spread of the new style. If we start by looking at the sources and influences we are left with, from the contemporary period, Cubism for geometric deconstruction, Orphism and Fauvism for the use of bold colour, the Ballet Russes for bringing all the previous elements together plus ethnographic colour, the exotic as exemplified by China, Japan, the Middle East, Africa, Oceania. Art Deco can certainly be seen as utilizing many disparate sources for inspiration and ultimately the development of a new architectural vocabulary.

After the end of the First World War, there were obvious challenges to be met. In many parts of Europe reconstruction was essential; key infrastructure, housing, public buildings, including religious buildings, and business activity. In addition, technological developments in travel required new buildings to accommodate flying and especially passenger flight. Travel by sea was also an impetus for more stylistic development, as the great ocean liners were built. The first truly worldwide mass media, radio and cinema, required building infrastructure, and importantly film was a vehicle for the dissemination of ideas and the shaping of style – especially that emanating from Hollywood, which would come to dominate the world and through this medium export American values and certainly the American brand of Art Deco architecture and design to the rest of the world in the most effective and pervasive manner yet seen.

Gunnar Asplund, Stockholm Public Library, Sweden. 1928.

What also needs to be remembered is that many of the colonial empires were at their zenith. As such, their ability to control and dictate architectural taste amongst other things in many unexpected corners of the globe would lead to remarkable displays of contemporary Art Deco architecture. As a result, places as far apart as Asmara in Eritrea, (then part of Abyssinia and the Italian African Empire), Hanoi in Vietnam (part of French Indochina), Mumbai (then Bombay, part of the British Indian Empire), are full of outstanding buildings that represented the very latest in international styles. This aspect of the spread of Art Deco will be discussed more fully in Chapter 4.

New opportunities

All the infrastructure developments required new buildings. The emergence of new materials fed into the interwar developments and supported the redefinition of concepts in building and decoration. The growth of radio and film would create the demand for broadcasting stations, transmitters, cinemas and a new generation of concert halls.

The new mania for larger shopping outlets and the development of country-wide chains would allow opportunities for a future introduction of standardized properties on every high street. Hotels in most large cities and capitals would also reflect this desire for a new and exotic style. The seaside areas provided more opportunities for housing for all classes of society that would reflect the new age. No survey of Art Deco architecture would be complete without referencing the impact that Art Deco had upon housing. Although, from the residences of the super rich, whether mansions, villas or through the building of suburban estates and on into social housing schemes, the impact of Art Deco was at best patchy in its implementation in usage around the world.

Basil Ionides, Savoy Hotel, London, entrance canopy. 1928. The statue of Count Peter of Savoy is by Frank Lynn Jenkins.

In a large number of countries, but especially the USA, state projects such as government buildings (for example court houses, town halls, post offices and so on) and the larger nationally/state funded schemes such as dams and power stations would as a matter of course look to be up-to-date and modern. It is perhaps with the corporate headquarters of companies and banks that Art Deco came to the fore, especially in the USA with a string of buildings in most major American cities that have grown to be synonymous with and representative of the style. Many of the corporate and organizational headquarters (along with hotels) gave opportunities for the interior architects of the period to develop an amazing series of interiors. These would reflect not only the crossover between the film sets of Hollywood movies, but also the artistic and indeed archaeological influences of the period.

Arthur Peabody, State Office Building, Wilson Street, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 1930–1959. View of building from the Monona Terrace.

Arthur Peabody, State Office Building, Wilson Street, Madison, Wisconsin, USA. 1930–1959. Detail of entrance on north side of complex.

In the field of entertainment, zoos and aquaria would embrace and realize many Art Deco buildings. Religion, and the need for new places of worship, is often completely overlooked. The growth in populations meant that there were chances around the world for Art Deco to appear in a range of guises, styles and sizes in churches, chapels and synagogues.

Echoes of the Past

And there were other cultural areas that had an impact on style. The period between the two World Wars was one of a remarkable series of archaeological discoveries, which captured the imagination of the world.

Chief amongst these was of course the discovery of the intact tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun in 1922, but also the rediscovery of the Mesopotamian civilizations, and in the Americas the continued rediscovery of Pre-Columbian cultures such as Mayan, Aztec, Olmec, Toltec, Inca and Anasazi. The continued central role of Hellenic civilization would remain a constant during this tumultuous period. The influence of Japan, China, India and the Far East still played a pivotal role across all aspects of visual culture in the West. Finally ethnography, with renewed interest in First Nation American cultures, Oceanic as well as African, also provided fresh stimulus with regard to decorative features.

These overlays of different cultures from around the world offered many fresh ideas to architects, designers and artists alike, driving Art Deco forwards in the quest for a new approach and solutions.

Archaeological discoveries held the imagination of general public in complete thrall. Agatha Christie was married to Max Mallowan who, as a leading Middle Eastern archaeologist, was responsible for important excavations and discoveries in what is today Iraq. The backdrop of these excavations would be fertile ground for Agatha Christie in her future detective novels. Likewise the discovery of Tutankhamun and the subsequent rush of ‘mummy’ movies enthralled the cinema, and biblical and ancient historical epics resulted in the continued fascination with all things ancient Egyptian throughout the period.

The enduring presence of Graeco-Roman civilization cannot be forgotten either. Closer in time, the craftsmanship of Louis Philippe and Louis XV must be considered.

Already it is a lengthy list – and yet that is only the beginning.

The Golden Age of Transport

However, it was the newer alternative transportation methods which embraced the emerging architectural style with the most vigour. The development of aviation and passenger flights meant aerodromes, hangars, airport buildings and so on. The world’s first international airport would be started at Croydon in South East London, though beyond the central building and control tower few vestiges of its glorious past remain. Not surprisingly, in Britain it is the smaller airports, which have long been bypassed, that have survived – in some cases intact. Chief amongst these is Liverpool Speke airport and Shoreham (Brighton) airport. Around the world it is a similar story where redevelopment, war and deliberate demolition have obliterated all but a handful of airports.

Amongst those that no longer survive, the first Amsterdam Schiphol airport terminal (1929) had learnt from the precedents at Croydon and Hamburg but also the contemporary work of Willem Marinus Dudok at Hilversum. German bombing in 1940 would destroy it.

In America, where the sheer size of the country meant that air transport was really the only viable means of fast, effective transportation, a whole network of airports sprang up all over the country.

Hugh Pearman wrote:

‘Every country brought its own architectural heritage to the building of the airport. In America there was at first no consensus as to the appropriate style. Kansas’ Fairfax airport (1929) by Charles A. Smith was Art Deco; Washington airport (1930) by Holden, Scott and Hutchinson was Moderne; the first St Louis airport and the first (1931) New York airport terminal at Floyd Bennett Field were neo-colonial; Albuquerque (1936–9) by Ernest H. Blumenthal was in the adobe manner; and a number of West Coast airports, including most notably San Francisco (1937) by H.G. Chipier were in Spanish-pueblo style; Chicago as we have seen was International Modern, while Miami and New York’s later La Guardia, both by Delano and Aldrich, concocted a style of Moderne going on Art Deco…’4

To this ever-lengthening list should be added the abstract conceptions – speed, modernity, glamour, wealth, escapism, which permeate so much of the output of Art Deco, not just the architecture but design and art in general. Marine architecture, best expressed in the great ocean liners, clearly represents these more abstract attributes during the period.

Edward Bloomfield, terminal building and control tower, Speke Airport, Liverpool. 1937–1939.

The glamour associated with the passenger liners of the 1920s and even more so the 1930s represented the final word in luxury; floating hotels, the embodiment of not only the values of their respective countries but the best in Art Deco architecture and design. Their size and the numbers that they carried demanded a new generation of buildings and dockside facilities to service them. France produced two new specialized buildings at its Atlantic ports, Cherbourg in 1933 and the Gare Maritime in Le Harvre (1935), which was in many ways the leader of this new generation of buildings, and certainly architecturally the most sensational. All countries with a maritime merchant fleet invested in similar buildings, each seemingly trying to outdo their rivals.

Naples (1936) produced a building that was designed to embody the aspirations of Mussolini’s Fascist Italy. Typically for Britain, perhaps, Southampton had to wait until 1950 to finally realize its wonderful Streamline Moderne Ocean Terminal. It would last barely thirty years before being unceremoniously demolished in 1983 as surplus to requirements. The travesty of a new terminal and multi-storey car park so recently built to cater for the revival in cruise lines is a poor ghost of what had been.

The Queen Mary berthed at Long Beach, California. 1936.

For the first time in architectural history, there was an exchange of ideas between architects and marine architects; the result was a remarkable synthesis of everything Art Deco – the ocean-going liners. With national pride at stake, countries vied to gain the famous Blue Riband for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic, with the emphasis on speed and hedonistic luxury. The great liners such as the Bremen, Queen Mary and Normandie were not just ships but floating examples of a perfect fusion between architecture, marine architecture, design and the fine and applied arts. Indeed, in the case of the Normandie, the liner was seen by the French government as more than a political statement; rather a floating advert for all that was best in terms of contemporary technology, art and design.

As a result, the project was underwritten by the French government. In Britain the contrast could not have been greater. When work on the Queen Mary came to a grinding halt due to a lack of finance, the project simply stopped. It was only once the government had forced the merger between White Star Line and Cunard that finance was provided to finish the project. With a delay of over a year, the Queen Mary had some catching up to do with its rivals, both in terms of speed and reputation.

Such was the link in people’s minds between the architecture, design and passenger liners that in Australia the new architectural style went under the name of ‘ship style’.

Alongside the building of the aforementioned magnificent liners, which were not only technological masterpieces but in addition the pride of their respective countries, there were the unrealized plans for even more ambitious ocean liners. Chief amongst these was the streamlined vision of the American industrial designer, Norman Bel Geddes. His 1932 unrealized designs were decades ahead of their time. These designs, along with his seminal book on streamlining, Horizons (1932), really popularized and promoted the style during the 1930s.

The Impact of the Silver Screen

Whilst it is impossible to quantify the impact of different influences, further mention must be made of the film industry, culturally the greatest mass entertainment achievement of the twentieth century. As a worldwide phenomenon it would reach its zenith during the 1930s and audience figures would peak just after the Second World War in 1946. Although most Western countries had their own film industries – Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and so on – it was Hollywood that reigned supreme.

The power of Hollywood films and the cinemas in which people watched them must not be underestimated. During the 1920s and 30s, the cinema was the number one form of mass entertainment and as such was the pre-eminent propaganda vehicle. No town or city was without its stylish new cinema; the names from this period – Gaumont, ABC, Alhambra and above all (in Britain) the Odeon – all purveyed a particular Art Deco style and a sense of excitement, modernity and a splash of glamour.

In his highly important book, Designing Dreams: Modern Architecture in the Movies, Donald Albrecht stated:

‘No vehicle provided as effective and widespread an exposure of architectural imagery as the medium of the movies. Statistics of cinema attendance during the first half of the century suggest the ability of the movies to rival, if not actually surpass, exhibitions as a major means of promoting new design concepts. Consider that the New York World’s Fair of 1939–40 attracted forty-five million visitors in eighteen months, while a scant 33,000 saw the 1932 New York mounting of the Museum of Modern Art’s Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which was instrumental in defining the new architecture for the United States. Then consider that shortly after World War I a single picture palace like Chicago’s Central Park entertained 750,000 moviegoers in its first year of business alone. By 1939, weekly attendance at America’s 17,000 movie houses was an astonishing 85,000,000, whilst seven years later, Hollywood’s best year in domestic attendance figures, the number had reached 98,000,000 moviegoers’.5

In Britain, approximately 3,000 cinemas saw a total attendance figure for 1935 of 912.3 million. As with America, the all-time high was recorded in 1946 when there were 1 billion, 635 million ticket sales (America reaching over 5 billion, 100 million annual ticket sales). 6

The role of the art director (sometimes individual artists/designers were brought in to design just specific sets within the film) is of crucial importance. Many of the set designers were trained as and practised as architects. In France, Robert Mallet-Stevens, who would become one of the seminal figures in French Modernist architecture, was particularly important as a film set designer. His work on the film L’Inhumaine also featured sets designed by Fernand Leger. In Germany, Franz Schroedter (who worked with Fritz Lang) was particularly fascinated by the architecture and furniture of the Bauhaus. Hollywood was already receiving waves of immigrant expertise from Europe and the latest international styles were particularly reflected in the output of three studios, namely Paramount, MGM and RKO. The German-trained presence was particularly strong at Paramount and included Hans Drier (who regularly worked with the producer Ernst Lubitsch) and Kem Weber.

Overview

This book sets out to chart and make sense of the development and cross-fertilization between styles and the development of subsets, regionally and nationally. This in turn will be examined in the light of the connections between the dynamic socio-political and economic situation that played out in the interwar years. What is in many ways the disorderly picture, architecturally speaking, means that to keep from complete confusion, it is necessary to set out a fairly standard typology in terms of looking at buildings of similar use in each country. In this way the choice of a combination of famous and not-so-famous buildings in the various categories does not become a straightforward line-up of all the churches, then all the airports. Rather, to allow for the national and regional varieties, I have kept the buildings to their respective countries.

It is an interesting question: whilst most people can name perhaps one of the iconic products of Art Deco architecture, can anyone name the architects? Certainly, in all of the countries covered in this book, the cult of the superstar architect seemed to skip the Art Deco period.

Yet there were a handful of great architects whose output and development in style should on those points alone warrant their inclusion in the lists of great architects of the twentieth century. Alongside the household names such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Sir Edwin Lutyens, Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, should reside the likes of Raymond Hood, Cross and Cross, Charles Holden, Wallis Gilbert and Partners, Paul Cret, Robert Mallet-Stevens et al. Therefore in each of the relevant chapters I have devoted time and space to proclaim the genius of such architects and highlight their often extraordinary contributions to architecture and the very visual make-up of the period. Their work, such as still exists, demands their rightful place amongst the pantheon of great architects.

Chapter 1

POST-FIRST WORLD WAR FRANCE

From The Start of a New Architectural Vocabulary and Style to Classical Modernism

Théâtre des Folies-Bergère, Paris. Detail of relief sculpture by Maurice Pico, of the dancer Anita Barka. 1926–27.

France – the birthplace of Art Deco. Some of its proponents/practitioners are very well known: furniture makers, Jacques Rhulemann; jewellers, Raymond Templier; interior decorators, Jean Dunand. Perhaps beyond the name of Le Corbusier and possibly Robert Mallet-Stevens, most people would find it difficult to summon up the names of any other French architects working during this period. To list just a few of the most important names is to shine a necessary spotlight on a little-known group who deserve so much more attention: Yves Hémar; Desmet and Doutrelong; Auguste and Gustave Perret; Robert Mallet-Stevens; Joseph Hiriart; Emile Bluysen ; Pierre Patout; Emile Dubuisson; Henri Sauvage; Henri Zipcy; Louis-Hippolyte Boileau; Auguste Bluysen; Albert Laprade; Georges-Robert Lefort; Michel Roux-Spitz. Of these, a small number are represented in the architects’ case studies.

Building for the Future

With the Armistice and the subsequent reparations set by the Treaty of Versailles, France set about rebuilding its economy and the shattered towns, villages and cities of much of the north and east of the country. Such was the scale of the devastation and demand for new building that in places such as Arras, Lens, Lille and Nancy, whole towns and city districts would emerge in a new and radical departure from the pre-war dominant style of Art Nouveau and late nineteenth-century Haussmann-inspired Neo-Classicism.

Plaster decoration, stylized classical bowl of flower heads, Lille.

With its emphasis on greatly reduced and stylized decorative schemes, regional variations, historicism and the use of regional materials, this led to the development of a uniquely French style that in turn would be disseminated around the world. The opportunities that arose produced a new set of architectural champions, such names as Albert Baert, Albert Laprade and Emile Dubuisson, most of whose names today barely gain regional let alone national or international recognition.

France was quite unusual compared to its fellow Allies, having lost a significantly greater portion of its population in the First World War than any of its major Western Allies (some 1.4 million dead soldiers; 400,000 civilians killed and 4.2 million wounded) and proportionately suffered the greatest physical damage through invasion and war. In fact, the occupied portion of Northern and Eastern France made up just under 5 per cent of the French landmass, but that heavily industrialized region accounted for 64 per cent of its pig iron output, 24 per cent of its steel production and 40 per cent of its coal production.

Architecturally speaking, French Art Deco really starts prior to the First World War with one particular building, the radically designed Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris, which was the work of Auguste Perret. The building, which was constructed between 1910 and 1913, would also go down in history for the most famous musically inspired riot in a theatre, caused by the first public performance of Stravinsky’s TheRite of Spring. The building certainly pointed the way forward, with its rather austere and mainly plain external facades graced only by the frieze of bas-relief panels, sculpted in what would become an Art Deco style by Antoine Bourdelle.

Auguste Perret, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Paris. 1911–13.

This building shares the distinction of being one of the earliest of its kind, along with Henri Sauvage’s first Art Deco designed structure, the 1913 Majorelle, also in Paris.

The First World War had halted any further development. Indeed the proposed government-sponsored international exhibition would also be put on hold until 1925. It is now widely seen that without the First World War, the development and introduction of Art Deco in France and beyond would have almost certainly taken place a decade prior to its much-heralded 1925 arrival.

The Treaty of Versailles would take into account the vast scale of reparation necessary to repair and rebuild.

Financially, France initially weathered the vagaries of the period relatively unscathed. The banking sector did not suffer nearly as badly as either Britain or America. This was partly due to the reparation payments being made by Germany and partly through government intervention to stave off rampant inflation. Taxes were increased and tax collecting improved. Whereas the American and British systems collapsed in 1929 to be followed by the devaluation of their currencies, France would manage to stave off the worst effects of the Great Depression until 1931 and devaluation of the Franc until 1936. The country’s unemployment never rose above 5 per cent. This relative financial stability supported ongoing reconstruction. The most important encouragement at the start of the period was the massive programme of rebuilding. The rebuilding would, of course, have a regional bias, as much of the country was physically unaffected by the war. I have chosen to spotlight the reconstruction in and around Lille. There was however an enormous amount taking place in other areas of the country such as Alsace Lorraine, particularly Nancy, and all along the site of the Western Front. These areas of reconstruction would very much incorporate the regional vernacular with the newly emergent decorative features, to bring forth a range of new hybrid styles.

Facade in Arras, stucco rendered with geometric forms and classical figure.

Facade in Arras, stucco rendered with stylized bowl of flowers.

Facade in Arras, stone faced with simple geometric forms.

Facade in Arras with stucco rendering, exposed brickwork, stylized wave pattern and geometric forms in coloured plaster. Wave pattern metalwork balconies.

In North Eastern France, such places as Arras and Bailleul would be reconstructed very much in a traditional regional and therefore Flemish-inspired vernacular. Arras in particular would restore its famous squares in an exact copy of the destroyed Dutch Flemish originals, whilst the Baroque cathedral would be recreated with some interesting internal Art Deco decorative touches. In Lens however, the opportunity was taken to rebuild most of the civic and public buildings in a more contemporary style, with the miners’ baths, railway station, town hall, post office and so on all taking on a distinctively fresh appearance. Now, smooth geometric shapes were being mixed with pared-down, highly stylized, largely floral decorative panels and features.

Outside of the war-ravaged regions, Art Deco took hold regionally in the seaside vacation areas of Brittany, the south-west Atlantic coast and most importantly the Riviera. In the major cities, such as Lyon, Toulouse, Marseilles, a familiar pattern emerged, with some public buildings and factories appearing in a variety of Art Deco styles.

Facade in Arras with stucco rendering, exposed brickwork, stylized wave pattern and geometric forms. Wave pattern metalwork balconies.

The Paris Exhibitions

However, it is in Paris where the impetus of major international fairs and exhibitions fuelled a particularly rich creation of Art Deco buildings. The exhibitions in Paris of 1925, 1931, 1934 and 1937 in particular acted not only as a showcase for French art, architecture and design, but also allowed for the ideas of other countries and other styles to stand alongside one another. In the case of the glorious so-called highpoint of Art Deco at the 1925 exhibition, there were three major Modernist interventions.

Firstly, and perhaps most famously, Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau, the Soviet Union’s Pavilion and Robert Mallet-Steven’s information kiosk and tower, which would become a landmark at the 1925 exposition, all pointed to radically different alternatives to the newly emergent Art Deco.

Whereas neither the 1925 nor the 1934 exhibitions left permanent in situ buildings, the exhibition of 1931, the International Colonial Exposition, left Paris with one building, the Museum of the Colonies at La Porte Dorée. Built by Albert Laprade, Léon Bazin and Léon Bazin and Leon Jaussely, its long colonnade and front wall have bas-reliefs by Alfred Janniot, in a typically French use of Neo-Classicism with Art Deco flourishes.

The sculptures depict animals, plants and cultures from the French colonies. Finally, the 1937 Paris international exposition has left twice as many buildings as all of its interwar predecessors. Despite its relative lack of contemporary popular success, its buildings have certainly left Paris with a spectacular legacy. The Palais de Chaillot designed by Jacques Carlu, Louis-Hippolyte Boileau and Léon Azéma is on a monumental scale, heavily influenced by Neo-Classicism and built out of concrete and stone.

Opposite this and again in a Neo-Classical style is the Palais d’Iéna. Not far away is the Palais de Tokyo, now home to the Paris City Museum of Modern Art.

Finally, there is the former Museum of Public Works, again in a Neo-Classical inspired style, this time designed by Auguste Perret, with a colonnade, rotunda and impressive façade. Now it serves as the French Social and Environmental Council. It was all built (not surprisingly for Perret) out of reinforced concrete.

These exhibitions taken as a whole would likewise reveal the steady change that was taking place as Art Deco transformed itself, with the currents of European Modernism, the Bauhaus, Constructivism, American Art Deco in the guise of Streamline Moderne and eventually International Modernism, all rapidly transmogrifying into a style that was also effectively acting as a barometer of public taste, aspiration and ambition in the light of the gathering political storm clouds.

Exterior view of the former Museum of the Colonies Building at La Porte Dorée. Paris. 1934. Architects Albert Laprade, Léon Bazin, Léon Jaussely. Bas-reliefs carved by Alfred Janniot.

Detail of bas-relief carvings on exterior of La Porte Dorée by Alfred Janniot. 1934.

Palais de Chaillot, Paris. 1937. Architects Jacques Carlu, Louis-Hippolyte Boileau and Léon Azéma.

Palais de Tokyo, Paris. 1934–1937. Architects Jean-Claude Dondel, André Aubert, Paul Viard and Marcel Dastugue.

In all the regions of France there was a fairly rapid move from the initial vernacular decorative styles towards buildings that would assimilate or imitate American-inspired Streamline Moderne, or European Modernism or combinations of these two overriding influences. What would disappear very quickly were the rather quirky, original, naturalistic decorative panels, mixed with Stripped Classicism that also appeared in the decorative metalwork that gave French Art Deco its original and playful exuberance. Some of the government contracts for buildings such as post offices also started to appear in a late, very restrained Art Deco style.

Rebuilding Lille

Returning to the metropolitan area of Lille, we find a good example of how a city in barely thirty years went through these developments. There were a number of architectural practices working in the region and their work would not only reflect their abilities and tastes, but also the range of styles being demanded by various clients.

The Germans had occupied Lille throughout the course of the war. It was just far enough back to act as a major supply and rest base for the front lines that were a matter of just ten miles or so distant on a curving trajectory to the north and west.

There was a great deal of damage caused by the Germans when they took over, deliberately blowing up some hundreds of houses and buildings. This and the post-war growth would create a demand and a new approach to redevelopment. Throughout the city there are pockets of redevelopment and further out, new suburban development.

The Lille region is not, historically speaking, an area that used great amounts of stonework; its natural resource to hand was always clay and therefore brick. Brick would take its place alongside reinforced concrete to maintain the local vernacular traditions. This would lead to some remarkable displays of the bricklayer’s art and decorative brick exuberance. As the region that supplied so much of the pig iron production of France, it is not surprising that there is also an emphasis on the use of decorative ironwork in the balconies, doors and so on in Art Deco buildings of all types.

Lille, apartment block. 1931. Architect C. Giovannoni.

Lille, detail of gilded brickwork. No. 19, Rue de l’Hôpital-Militaire.

Lille, detail of patterned brickwork. No. 19, Rue de l’Hôpital Militaire.

Lille, detail of iron balcony decoration.

Lille, detail of decorative tile work, shop facade. No. 19, Rue de l’Hôpital Militaire.