13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Legorreta

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Spanisch

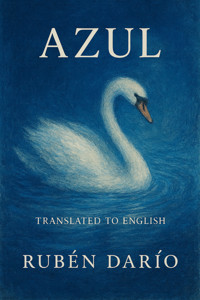

Azul... (1888) by Rubén Darío is considered the foundational work of the Modernismo literary movement in Spanish-language literature. Written when Darío was only twenty-one, the book is a collection of poems and short stories that revolutionized the use of language, imagery, and rhythm in Hispanic poetry and prose. Published in Valparaíso, Chile, Azul... reflects Darío's fascination with beauty, art, and imagination. The title—meaning "Blue"—symbolizes idealism, purity, and the infinite, evoking the color of the sky and the sea. The book blends fantasy, musicality, and sensual imagery, drawing inspiration from French Symbolism and Parnassianism while introducing a distinctly Latin American voice. Among its most notable texts are El rey burgués, Sonatina, and El velo de la reina Mab, which explore the tension between materialism and artistic idealism. Through mythological references, exotic settings, and musical language, Darío defends art's power to elevate the spirit above the mundane. Azul... not only transformed Spanish literature but also established Rubén Darío as the "Prince of Spanish Letters," inspiring generations of poets to seek harmony, innovation, and beauty in expression.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Index

I

II

The Bourgeois King

The Deaf Satyr

The Nymph

The Bundle

The Veil of Queen Mab

The Song of Gold

The Ruby

The Palace of the Sun

The Blue Bird

White Doves and Brown Herons

In Chile: In Search of Paintings

Watercolor

Landscape

Strong Water

The Virgin of La Paloma

The Head

Watercolor I

A Portrait by Watteau

Still Life

To Cheron

Xi Landscape

The Ideal

The Death of the Empress of China

To a Star

The Lyrical Year

Summer

Autumnal

Winter

Autumn Thoughts

To a Poet

Anagke

Sonnets

Venus

Winter (Variant)

Medallions

Catulle Mendies

Walt Whitman

J. J. Palma

Salvador Díaz Mirón

End

TO DON RUBÉN DARÍO I

Madrid, October 22, 1888.

EVERY book that comes into my hands from America excites my interest and arouses my curiosity; but none until today has aroused it as vividly as yours did, as soon as I began to read it.

I confess that at first, despite the kind dedication with which you sent me a copy, I looked at the book with indifference...almost with aversion. The title Azul... was to blame.

Victor Hugo says: L'art cest l'azur; but I do not agree or resign myself to the fact that this saying is very profound and beautiful. For me, it is as valid to say that art is blue as saying that it is green, yellow, or red. Why?

In this case, blue (although in French it is not bleu, but azur, which is more poetic) must be a cipher, a symbol, and a higher predicate that encompasses the ideal, the ethereal, the infinite, the serenity of the cloudless sky, the diffuse light, the vague and boundless expanse where the stars are born, live, shine, and move. But even if all this and more arises from the depths of our being and appears to the eyes of the spirit, evoked by the word blue, what is new in saying that art is all this? It is the same as saying that art is an imitation of Nature, as Aristotle defined it: the perception of everything that exists and everything that is possible, and of its reappearance or representation by man in signs, letters, sounds, colors, or lines. In short: no matter how much I think about it, I see nothing in this idea that art is blue but an and empty.

Be that as it may, art is blue, or whatever color you want it to be.

As long as it's good, the color is the least important thing. What gave me a bad feeling was Victor Hugo's phrase, and the fact that you had used the key word from that phrase as the title of your book. Could this be, I asked myself, one of the many, many people everywhere, especially in Portugal and Spanish America, who have been infected by Victor Hugo? The mania for imitating him has wreaked havoc, because daring youth exaggerates his faults, and because that thing called genius, which makes faults forgivable and perhaps even applauded, cannot be imitated when one does not possess it. In short, I suspected that you were you were a Victor Hugo wannabe and I didn't read your book for over a week.

As soon as I read it, I formed a very different opinion.

You are a person of great originality and very strange originality. If the book, printed in Valparaíso in 1888, were not written in very good Spanish, it could just as easily have been written by a French, Italian, Turkish, or Greek author. The book is imbued with a cosmopolitan spirit. Even the author's first and last names, whether real or invented, make the cosmopolitanism stand out even more. Rubén is Jewish, and Darío is Persian; so, based on the names, it seems as if you want to be or are from all countries, castes, and tribes.

The Blue Book... is not really a book; it is a pamphlet; but it is so full of things and written in such a concise style that it gives one much to think about and has quite a lot to read. It is clear that the author is very young: he cannot be more than twenty-five years old, but he has made wonderful use of them. He has learned a great deal, and in everything he knows and expresses, he displays a singular artistic and poetic talent.

He knows ancient Greek literature with love; he knows everything about modern Europe. One can glimpse, although he does not flaunt it, that he has a thorough understanding of the visible world and the human spirit, just as this concept has come to be understood formed by the most recent observations, experiences, hypotheses, and theories. And it is also clear that all of this has penetrated the author's mind, not exclusively, but mainly through French books. What's more, there is so much French in the author's profiles, refinements, and exquisiteness of thought and feeling that I made up a story to explain it to myself. I assumed that the author, born in Nicaragua, had gone to Paris to study medicine or engineering, or another profession; that he had lived in Paris for six or seven years, with artists, writers, scholars, and cheerful women from there; and that much of what he knew he had learned firsthand, empirically, through his interactions and contact with those people. It seemed impossible to me that in such a way had imbued the author with the very latest Parisian spirit without having lived in Paris for years.

I was extraordinarily surprised to learn that, according to well-informed sources, you have not left Nicaragua except to go to Chile, where you have been living for two years at most. How, without the influence of the environment, have you been able to assimilate all the elements of the French spirit, while retaining Spanish form that unites and organizes these elements, turning them into your own substance?

I don't think there has ever been a similar case involving a Spaniard from the peninsula. We all have a deep-rooted Spanish spirit that no one can take away from us, even with twenty-five pulls.

In the famous Abbot Marchena, despite having lived in France for so long, you can see the Spaniard; in Cienfuegos, it is the cloying Rousseau-like sentimentality is artificial, and the Spanish spirit lies beneath. Burgos and Reinoso are Frenchified, not French. French culture, good or bad, never goes beyond the surface. It is nothing more than a transparent veneer, behind which the Spanish character is revealed.

None of the men of letters from the Peninsula whom I have known, with a more cosmopolitan spirit, who have lived in France for longer and who have spoken French and other foreign languages better, have ever seemed to me to be as attuned to the spirit of France as you seem to me: neither Galiano, nor Don Eugenio de Ochoa, nor Miguel de los Santos Álvarez. Galiano speaks like a mixture of Anglicism and French philosophism of the last century; but all superimposed and not combined with the essence of his spirit, which was pure. Ochoa was and always remained fiercely and ultra-Spanish, despite his enthusiasm for all things French. And in Álvarez, whose mind is teeming with the ideas of our century and who has lived in Paris for years, the essence of the Castilian man is deeply rooted, and in his prose the reader is reminded of Cervantes and Quevedo, and in his verses of Garcilaso and León, although in both verse and prose he always expresses ideas more typical of our century than of those that have passed. His wit is not French esprit, but rather the Spanish humor of picaresque novels and the comic authors of our unique literature.

I see, then, that there is no author in Spanish more French than you, and I say this to state a fact without praise or censorship. In any case, I say it rather as a compliment. I do not want authors to lack national character, but I cannot demand that you be Nicaraguan, because there is not and cannot yet be a literary history, school, or traditions in Nicaragua. Nor can I demand that you be Spanish in literary terms, since you are no longer Spanish in political terms, and you are also separated from the mother country by the Atlantic, and even further away in the Republic where you were born from Spanish influence than in other Spanish American republics. With the Gallicism of the mind thus excused, I must praise you profusely for the perfection and depth of that Gallicism, because the language remains Spanish, legitimate and proper, and because if you do not have a national character, you do have an individual character.

In my opinion, you have a powerful individuality as a writer, already well marked, and if God grants you the health I wish for you and a long life, it will develop and become more prominent over time in works that will be the glory of Spanish American literature.

Having read the pages of Blue... the first thing you notice is that you are saturated with all the most brilliant French literature. Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, Baudelaire, Leconte de Lisle, Gautier, Bourget, Sully-Prudhomme, Daudet, Zola, Barbey d'Aurevilly, Catulle Mendes, Rollinat, Goncourt, Flaubert, and all the other poets and novelists have been well studied and better understood by you. And you imitate none of them: you are neither romantic, nor naturalist, nor neurotic, nor decadent, nor symbolic, nor Parnassian. You have mixed everything together: you have put it all into the still of your brain and distilled from it a rare quintessence.

The result is a Nicaraguan author who never left Nicaragua except to go to Chile, and who is such a fashionable author from Paris, so chic and distinguished that it anticipates fashion and could modify and impose it.

The book contains prose stories and six compositions in verse. In the stories and poems, everything is chiseled, engraved, made to last, with care and precision, as Flaubert or the most dapper Parnassian might have done dapper Parnassian. And yet, the effort and work of the file, the fatigue of searching, are not noticeable; everything seems spontaneous and easy, written as the pen flows, without detracting from the conciseness, precision, and extreme elegance.

Even the extravagant and outrageous oddities, which shock me but may be generally appealing, are done on purpose.

Everything in the book has been carefully considered and critiqued by the author, without his prior or simultaneous criticism of the creation detracting from the passionate verve and inspiration of the creator.

If I were asked what your book teaches and what it is about, I would answer without hesitation: it teaches nothing, and it is about nothing and everything. It is the work of an artist, a work of pastime, of mere imagination. What does a cameo, an enamel, a painting, or a beautifully carved cup teach or deal with?

There is, however, a notable difference between any sculpture, painting, charm, or even music, and any object of art whose material is the word. I will not say that marble, bronze, and sound cannot mean something in themselves, but the word can not only mean something, it can necessarily means ideas, feelings, beliefs, doctrines, and all human thought. Nothing is more feasible, in my view (perhaps because I am not very sharp), than a beautiful statue, a pretty charm, an exquisite painting, without meaning or symbolism; but how can one write a story or a few verses without revealing what the author denies, affirms, thinks, and feels? Thought in all its forms passes from the artist's mind to the substance or matter of art; but in the art of artist to the substance or matter of art; but in the art of the word, in addition to the thought that art possesses in form, the substance or matter of the artist is also thought, and the thought of the artist. The only matter foreign to the artist is the dictionary, with the grammatical rules that govern the combination of words; but since neither words nor combinations of words can exist without meaning, matter and form in poetry and prose are the creation of the writer or poet; only the empty signs, so to speak, remain outside of him, that is, abstracting the meaning so to speak, the empty signs, that is, abstracting the meaning.

This explains how, even though your book is a pastime and has no purpose of teaching anything, the author's tendencies and thoughts on the most transcendental issues are evident in it. And it is only fair to admit that these thoughts are neither very edifying nor very comforting.

The science of experience and observation has classified everything that exists and made a skillful inventory of it. Historical criticism linguistics, and the study of the layers that form the Earth's crust have uncovered much about past human events that were previously unknown; we know a great deal about the stars that shine in the expanse of the ether; the world of the imperceptibly small has been revealed to us thanks to the microscope; we have found out how many eyes one insect has and how many legs another; we now know what elements make up organic tissues, animal blood, and plant sap; we have taken advantage of agents that were previously beyond human power, such as electricity; and thanks to statistics, we keep meticulous accounts of how much produced and how much is consumed, and if we do not yet know, we can expect to soon know the exact number of rolls, wine, and meat that humanity eats and drinks every day.

There is no need to consult profound scholars: any mediocre, average scholar of our age today knows, classifies, and orders the phenomena that affect the bodily senses, aided by powerful instruments that increase their capacity for perception.

Furthermore, through patience and insight, and by virtue of dialectics and mathematics, a large number of laws governing these phenomena have been discovered.

It is natural that the human race has become arrogant with such discoveries and inventions; but not only around and outside the sphere of the known, circumscribing it, but also filling it in its essence and substance, there remains an unexplored infinity, a dense and impenetrable darkness, which seems all the more frightening because of the very contrast with the light with which science has bathed the small sum of things it knows. Before, religions with their dogmas, accepted by faith, and metaphysical speculation with the giant machine of its brilliant systems, either concealed that unknowable immensity, or explained it and made it known in their own way. Today, the determination prevails that there should be neither metaphysics nor religion. The abyss of the unknowable is thus uncovered and open; it attracts us and makes us dizzy, and communicates to us the impulse, sometimes irresistible, to throw ourselves into it.

The situation, however, is not uncomfortable for sensible people of a certain level of education and standing. They disregard the transcendent and the supernatural so as not to rack their brains or waste their time in vain. This inclination removes many apprehensions and a certain fear, although at times it instills another annoying fear and alarm. How can the masses, the needy, the hungry, and the ignorant be contained without this restraint that they have so gladly discarded? Apart from this fear experienced by some sensible people, in everything else they see only reasons for satisfaction and congratulations.

The foolish, on the other hand, are not satisfied with the enjoyment of the world, embellished by human industry and inventiveness, nor with what is known, nor with what is manufactured, and they long to discover and enjoy more.

The whole of beings, the Universe, everything that can be perceived by sight and hearing, has been, as an idea, methodically coordinated in a shelving system or locker for better understanding; but neither this scientific order nor the natural order, as the foolish see it, satisfies them.

The softness and luxury of modern life have made them very discontented.

And so they form no very favorable opinion of the world as it is, nor of the world as we conceive it.

They see faults in everything, and they do not say what God is said to have said: that everything was good. People rush more than ever before to say that everything is bad; and instead of attributing the work to a supremely intelligent and supreme craftsman, they assume it to be the work of an unconscious Puritan who manufactures things that have existed since eternity in atoms, which they also do not exactly what they are.

The two main results of all this in the latest fashion in literature are:

1.° That God be abolished or that He not be lied to except to insult Him, either with curses and blasphemies or with mockery and sarcasm; and

2.° That in this dark and unknowable infinity, the imagination perceives, as in the ether, nebulae or seedbeds of stars, fragments and debris of dead religions, with which it seeks to form something like an essay of new beliefs and renewed mythologies.

These two features are imprinted in your little book: Pessimism, as the culmination of all description of what we know, and the powerful and lush production of fantastic beings, evoked or drawn from the darkness of the unknowable, where the ruins of shattered beliefs and ancient superstitions wander.

Now it would be good for me to cite examples and prove that your book contains, with remarkable elegance, everything I assert; but this requires a second letter.

II

On the cover of the book you sent me, I see that you have already published, or announced the publication of, several others, whose titles are: Epistles and Poems, Rhymes, Burrs,Critical Studies, Albums and Fans, My Acquaintances, and TwoYears in Chile. The cover also announces that you are preparing a novel, whose title strikes us right in the soul (for if the soul has eyes, or if the soul has a nose, it may well have a sense of smell), with a whiff of pornography. The novel is titled: The Flesh.

None of this, however, helps me to judge you today, as I know nothing about it. I have to limit myself to the book Azul...

In this book, I don't know which I prefer: the prose or the verse.

I am almost inclined to see equal merit in both modes of expression of your thoughts. The prose is richer in ideas, but the form is more Frenchified. In the verse, the form is more traditional.

Your verse resembles the Spanish verse of other authors, but that does not that they cease to be original; they are not reminiscent of any Spanish poet, either ancient or modern.

Your feeling for nature borders on pantheistic adoration. In the four compositions (or rather in) the four seasons of the year, there is the most gentile exuberance of sensual love, and, in this love, something religious.

Each composition seems like a sacred hymn to Eros, a hymn that, at times, in the greatest explosion of enthusiasm,s disturbed by pessimism with dissonance, either a cry of pain or a sarcastic laugh. That bitter taste, which springs from the very center of all delight, and which the atheist Lucretius experienced and expressed so well,

...medium of frute leporum

Something arises that hinders the flowers themselves, often comes to interrupt what you call

"The triumphant music of my rhymes."

But since there is everything in you, I notice in your verses, in addition to the longing for delight and the bitterness that Lucretius speaks of, a thirst for the eternal, that profound and insatiable aspiration profound and insatiable aspiration of the Christian ages, which the pagan poet might not have understood.

You always ask more of the fairy, and...

"The fairy then led me to the veil that covers our infinite desires,

the deep inspiration and

the soul of the lyres,

And she tore it. And there everything was dawn."

But even so, the poet is not satisfied, and asks the fairy for more.

You have another composition, entitled after the Greek word Anagke, where the love song ends in misfortune and blasphemy. Omitting the final blasphemy, which mocks God, I will include the song here almost in its entirety.

"And the dove said:

' I am happy. Under the vast sky, in the

blossoming tree, next to the apple full

of honey, next to the soft sapling damp

with dewdrops,

I have my home. And I fly

with my bird's desires,

from my beloved tree

to the distant forest,

when, to the joyful hymn

of the awakening of the East,

the naked dawn comes out and shows the world the modesty of light on its forehead.

My wing is white and silky;

the light gilds and bathes it and the zephyr combs it my feet are like rose petals.

I am the sweet queen

who coos to her dove in the mountains.

Deep in the picturesque forest

is the larch tree where I built my nest;

and there, under the cool foliage,

a newborn chick without equal. I am

the winged promise,

the living oath;

I am the one who carries the memory of

the beloved for the thoughtful lover;

I am the messenger

of the sad and ardent dreamers, who

flutters about whispering words of love

beside a perfumed head of hair.

I am the lily of the wind.

Under the blue of the deep sky I

show off my beautiful and rich

treasure, my medals and finery;

the cooing in my

beak, the caress in

my wings,

I wake the chattering birds and they

sing their melodic songs; I perch on

the flowery lemon trees and shower

them with orange blossoms. I am all

innocent, all pure.

I fluff myself up on the wings of desire.

And I tremble in the intimate tenderness of a touch, a whisper, a flutter.

Oh immense blue! I love you. Because you give Flora the rain and the ever-burning sun:

because being the palace of the dawn,

you are also the roof of my nest.

Oh immense blue! I adore your

smiling clouds,

and that subtle mist of golden dust

where perfumes and dreams go. I love the

veils, faint and slow,

of the floating mists,

where I spread the gentle fan of my

feathers to the loving air.

I am happy! For mine is the forest

where the mystery of the airs lies;

because dawn is my celebration