Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

The battle between good and evil—in both the seen and unseen worlds—was as clearly at play in the era of C. S. Lewis and his friends in the Oxford literary group, the Inklings, as in our own era. Some of the members of the Inklings carried physical and psychological scars from World War I which led them to deeply consider the problem of evil during the dark era of World War II. Were they alive today, their view of a spiritual conflict behind physical battles would undoubtedly be reinforced. Among the Inklings, Lewis was at the forefront of writing on human pain, suffering, devilry, miracles and the supernatural, with books like The Screwtape Letters and more. It is no surprise, then, that he provides the main focus of this book by expert Inklings writer Colin Duriez. J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy offers another rich resource with much to say to the World War II era and beyond. Other Inklings writings and conversations come into play as well as Duriez explores the writers' considerations of evil and spiritual warfare, particularly focused in the context of wartime.Delving into the interplay between good and evil, these pages enlighten us to the way of goodness and the promise of a far country as we explore the way out of the shadow of evil.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 368

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BEDEVILED

Lewis, Tolkien and the Shadow of Evil

COLIN DURIEZ

www.IVPress.com/books

InterVarsity Press P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL [email protected]

©2015 by Colin Duriez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press® is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA®, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visitintervarsity.org.

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version, copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

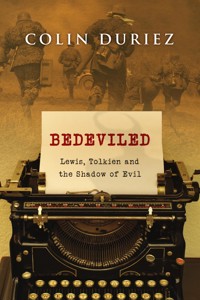

Cover design: Cindy Kiple Images: old typewriter:© slobo/iStockphotoWWII battle scene:© Johncairns/iStockphoto blank key from manual typewriter: © FlamingPumkin/iStockphoto

ISBN 978-0-8308-9812-1 (digital) ISBN 978-0-8308-3417-4 (print)

To Ian Blakemore

Contents

Introduction

Part 1: Understanding Evil During a Time of War

1 C. S. Lewis in Wartime The Cosmic Battle

2 Devilry and the Problem of HellThe Screwtape Letters

3 Inklings in Wartime Themes of Spiritual Conflict

4 Images of the Dark SideThe Lord of the Rings

5 Right and Wrong as a Clue to MeaningThe Problem of Pain and Mere Christianity

6 Exploring What Is Wrong with the World The Cosmic Trilogy

Part 2: The Intersection of Good and Evil

7 Progress and Regress in the Journey of LifeThe Pilgrim’s Regress

8 The Divide Between Good and Bad Tolkien’s “Leaf by Niggle” and Lewis’s The Great Divorce

9 The Power of Change The Chronicles of Narnia

10 Pain and LoveThe Four Loves, Till We Have Faces and A Grief Observed

11 Release from Hell’s Snares Lewis and the Road Out of the Self to Gain the Self

12 The Way of Goodness and the Far Country Narnia and Middle-Earth

Appendix 1: War in Heaven

The Roots of C. S. Lewis’s Concern with Devilry

Appendix 2: The Spirit of the Age

Subjectivism

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Praise for Bedeviled

About the Author

More Titles from InterVarsity Press

Hobgoblin nor foul fiend

Can daunt his spirit,

He knows he at the end

Shall life inherit.

THE PILGRIM SONG, JOHN BUNYAN

Introduction

There are dangers in talking about a cosmic battle between good and evil. Most of all, it implies for many people that a permanent battle is raging between the forces of darkness and light. This is far from the understanding of C. S. Lewis and his friends in the now famous Oxford literary group, the Inklings. They mainly saw a figure such as the devil not as equal with God but as a created spiritual being of some kind, an angel of high rank, who had turned deliberately to evil from his original goodness. Though we are used to thinking of the universe very much in material, physical terms, the friends believed—and Lewis was in the vanguard of arguing for—a larger view of reality, a supernatural one.

Nevertheless, it was clear to them that a battle between good and evil was in process, both in the unseen world and in the physical and psychological horrors of human warfare. Most of the core members of the Inklings had experienced battle in World War I. Some bore physical or mental scars. Were they alive today, their view of a spiritual conflict behind physical battles, which affected whether or not people could live at peace and free from terror, would undoubtedly be reinforced. J. R. R. Tolkien for instance considered that the weapons of Sauron, the Dark Lord of The Lord of the Rings, had been used by the allies as well as the enemy in World War II, and C. S. Lewis expressed grave doubts about the massive bombings of civilians.

Because, among the Inklings, Lewis was at the forefront of writing on human pain, suffering, devilry, miracles and the supernatural, he provides the main focus of this book. This is not to say that other Inklings members did not write extensively on these themes—most famously, Tolkien in his The Lord of the Rings. They therefore come into my book, where relevant, as much as possible in its short compass. The chronology of Lewis’s writings is followed to a large extent in part two. In part one, his writings are more tied into his experience of two world wars, even though the more recent war was not a firsthand one for him. In part one, we also look at Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, in its relevance to the imagery of war and evil. Tolkien’s story, of course, is well known throughout the globe in its original print form, and now through Peter Jackson’s blockbuster movie version.

It is worth pointing out from the onset that C. S. Lewis had no interest in writing literally about what goes on in the afterlife to satisfy curiosity about this. He doesn’t take up popular imagery that is supposedly describing what happens when the spirit leaves the body at death, imagery that might portray a tunnel with light in the distance (based on accounts of near-death experiences). His accounts of heaven and hell are very different from each other according to the purpose of the book: there are different sets of imagery in his dream story, The Great Divorce, which is about an excursion by bus from hell to the borderlands of heaven, and the Narnian story The Last Battle. The Screwtape Letters is cast in yet another pattern of imagery, in which hell resembles a mixture of rampant bureaucracy like in Hitler’s Third Reich and a ruthless modern corporation. His treatment of the afterlife and the supernatural world is therefore in stark contrast to Richard Matheson’s bestselling novel What Dreams May Come (also made into a movie), which claims to be based on research and to give factual details of heaven and hell. In his brief prologue to his reader, Richard Matheson says, “Because [the novel’s] subject is survival after death, it is essential that you realize, before reading the story, that only one aspect of it is fictional: the characters and their relationships.” He adds, “With few exceptions, every other detail is derived exclusively from research.”1 He even provides a bibliography, including titles that are based on theosophy, a movement which seeks hidden knowledge for enlightenment and salvation.

Lewis was careful to state the opposite. Where he writes fictionally about the unseen world, and heaven and hell, he is not writing factually and literally about the afterlife. He warned in his preface to The Great Divorce:

I beg readers to remember that this is a fantasy. It has of course—or I intended it to have—a moral. But the transmortal conditions are solely an imaginative supposal: they are not even a guess or a speculation at what may actually await us. The last thing I wish is to arouse factual curiosity about the details of the after-world.2

In his youth he had dabbled in the occult (ironically, this was in his long period as an atheist) and realized the dangers of its compulsive attraction for him. Though he firmly believed in the actuality of heaven and hell, in his fictional books he explored these realities through what he called “supposals” in stories of his own making—though these did draw upon the imaginations of other writers such John Milton, Dante and many others from his extensive reading. He also regarded biblical imagery of heaven and hell as authority of the first order. In The Problem of Pain and elsewhere he offered logical arguments defending the reality of heaven, hell and immortality, based on Christian doctrines as embodied in the historic church creeds.

C. S. Lewis could root our human struggles with good and bad in our ordinary lives now, because for him heaven and hell were best understood in relation to them. He had a central Christian worldview in which heaven, in the final analysis, is really the world as it was meant to be, and is now the future condition of the world, which is in process of being radically remade. Lewis once wrote, “To enter heaven is to become more human than you ever succeeded in being in earth; to enter hell, is to be banished from humanity.”3 This process began in the death and resurrection of Christ, which inaugurated the new creation. Hell is conversely the world stripped of meaning, twisted and despoiled beyond recognition. Compared with the reality of heaven, it is almost nothing (as Lewis brilliantly pictures in his The Great Divorce). One of the Inklings, Charles Williams, was fond of saying, “Hell is always inaccurate.” Places like Auschwitz or starving towns under siege in Syria’s civil war as I write are modern hints of what hell is like, real nightmare images of unutterable loss created by modern human wickedness. For C. S. Lewis, and for friends like Tolkien and Charles Williams, there are intelligent powers pitted against goodness that are bent on destroying or breaking what is good, such as our very humanity. This is why we get glimpses of hell starkly in places like Auschwitz or in acts like genocide, but also (as Lewis constantly reminds us) on an ordinary level in deliberately wrong choices we make that have far-reaching and escalating consequences for ourselves and others, very often those we love.

In the concern of Lewis and friends with the powers of good and evil, I suggest, lies a key to their global popularity and continued relevance in particular in the new millennium. They bring these powers home to us. Lewis applied traditional Christian teaching about the world, the flesh and the devil to modern, often subtle manifestations of evil. He did this with such freshness and imagination that readers of his fiction are often unaware of the presence of orthodox Christian teaching. Numerous readers who do not share Lewis’s faith have long enjoyed The Screwtape Letters, the most famous of his books on devilry, because of its uncanny realism about human foibles. The popularity of the book owes much to the unlikely but brilliantly successful combination of humor with exploring the serious subject of human damnation.

As well as particularly modern manifestations of evil such as global war, Lewis was concerned with the perennial problem of what he called “worldliness,” where we focus on this world alone, losing its context in the infinite vistas of the unseen, supernatural world. The limited perspective of worldliness is explored rigorously in The Screwtape Letters. The fact that other major figures of his literary circle of friends, such as Charles Williams and J. R. R. Tolkien, were also preoccupied with the lure of the dark side and the spell it casts gave Lewis moral support and encouragement as he explored difficult issues like devilry and human suffering.

An ancient meaning of spell in English is “story.” Lewis, like Tolkien and other friends, was casting a spell in telling his stories of temptation, the powers of good and evil, and ways out of entrapment to badness. During World War II he said,

Spells are used for breaking enchantments as well as for inducing them. And you and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the enchantment of worldliness. . . . Almost our whole education has been directed to silencing this shy, persistent, inner voice; almost all our philosophies have been devised to convince us that the good man is to be found on this earth.4

I mentioned that other major figures of his literary circle, the Inklings, such as Williams and Tolkien, were also preoccupied with the demonic and the associated problem of evil. Sauron, the lieutenant of Tolkien’s Satan, Melkor, dominates the plot of The Lord of the Rings, much of it being read as it was written to the Inklings. (Tolkien in fact dedicated the first edition to the group.) Charles Williams wrote several nonfictional and fictional works on a similar theme, including a historical study of witchcraft and his novel All Hallows Eve, which benefited from input from the Inklings. Lewis’s science-fiction stories Perelandra and That Hideous Strength (particularly the latter) were influenced by Williams and were among several of Lewis’s writings, including The Great Divorce, on a devilish or a related purgatorial theme. Tolkien’s short story “Leaf by Niggle” reflects the interest that the Inklings had in the topic of purgatory in the World War II years—perhaps their most important period.

The concerns with devilry and related issues like human suffering are also there in writings between the wars and after World War II, but the last war gave intensity to them. Such writings before and after the war include C. S. Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress (Lewis’s first work of fiction, which we shall explore in chap. 7) and the Narnian stories The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Prince Caspian and The Last Battle (see chap. 9). Writings from others include Charles Williams’s Descent into Hell (written before he became a member of the Inklings), and even Tolkien’s The Hobbit, with the terrifying dragon Smaug, the goblin-ridden mountains and the Battle of the Five Armies.

Some chapters of this book fill out the context of the concern of Lewis and his friends with devilry. The times they lived through helped to draw attention to the urgency of such themes, which could be decidedly unpleasant to write about (as Lewis found when writing The Screwtape Letters). The emotional and physical scars of World War I were reopened when the Inklings found themselves living through a second global conflict just over two decades later. Between the two modern wars, Lewis went through the dramatic changes of his movement from atheism to Christian belief. I have briefly portrayed some of the remarkable contrasts and similarities between the younger and older Lewis, as well as the concerns of the group of Lewis’s friends in the productive World War II years. This has meant focusing on the emergence of devilry and related themes of the human quest for heaven or descent into hell, and the search for a way out of the self. I also occasionally consider writings of Dorothy L. Sayers, a mutual friend of Lewis and Charles Williams, where particularly relevant. Ms. Sayers was famous for her crime stories featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, plays, broadcasts, translations and popular theology. Because of an important link C. S. Lewis forges between the concerns of the Inklings and those of Sayers, it is difficult to ignore her work when considering the “life-force” of the Inklings.5

The Screwtape Letters, more than any other book by a member of the Inklings, draws dramatic attention to the theme of devilry in their writings. How it began in Lewis’s mind gives a unique insight into the link between the lives of the Inklings and their writings that carried the theme of the very real powers of light and darkness.

part one

Understanding Evil During a Time of War

1

C. S. Lewis in Wartime

The Cosmic Battle

World War II had been running its course for less than a year. Wartime had brought many changes into C. S. Lewis’s life, but he valued the normality of attending his local Anglican church. On the Sunday morning of July 21, 1940, he left his home, The Kilns, briskly as usual, for nearby Headington Quarry and Holy Trinity Church. As he walked, the familiar wooded slopes of Shotover Hill were behind him, and he enjoyed the rural quiet. There was the occasional sound of traffic from the main road nearby, inevitable even early on Sunday so close to Oxford.

Just the Friday evening before, Lewis’s family doctor, “Humphrey” Havard, had driven up to The Kilns. It was not a medical visit to see him, Mrs. Moore, Maureen her daughter, or one of the evacuee children billeted with them. Havard was also one of his friends from the Inklings. As planned, they tuned in and listened on the radio to a speech by Hitler. The BBC provided a simultaneous translation. A possible answer to a puzzle occurred to Lewis as he listened—how was the German leader so convincing to so many? Though Lewis rarely read the daily newspapers, he of course knew Hitler’s claims were grossly untrue. Making what he blatantly called his “final appeal to common sense,” Hitler boasted, “It never has been my intention to wage war, but rather to build up a State with a new social order and the finest possible standard of culture.”1

Hitler’s emotive speech may have still tugged at Lewis’s mind in the quietness of his church that Sunday. England faced the very real danger of invasion by Hitler’s forces, driven and maintained like a machine. The Battle of Britain, one of the deciding battles of the war, had begun—just that very day, nearly two hundred patrols were sent up into the summer skies by the Royal Air Force in response to enemy aircraft threatening Britain. During the church liturgy and bad hymns (as Lewis regarded them) he found his thoughts turning to the master of evil, Satan. Somehow, the arrogant dictator resembled him—not least in the size of his ego and self-centeredness. In the jumble of thoughts jostling with words of a great tradition, it struck Lewis that a war-orientated bureaucracy was a more appropriate image of hell for people ignorant of the past than a traditional one. Here was Hitler bent on taking over and ruling European countries, including England. There was the devil, who had designs to exert his will systematically over all parts of human life, his ultimate aim being dehumanization—the “abolition of man,” as Lewis later called it.

Lewis’s brother Warren (“Warnie”) had been evacuated just a few weeks previously. This was just before many thousands of retreating British soldiers were snatched from the beaches and jetties of the nearest French port of Dunkirk by ships and by boats large and small. Warnie, a retired army major, had been called back the previous year into military service and dispatched to France, which had been partly occupied by German forces. That quiet Sunday afternoon Lewis told Warnie in a letter an idea that would germinate and grow, and eventually become The Screwtape Letters. The idea was for a book containing the correspondence between a senior and a junior devil. It resulted in an important figure in hell’s “Lowerarchy” (Screwtape, the senior devil) writing convincingly to Wormwood (the junior devil, Screwtape’s nephew) about devilish ways of winning over human beings or keeping them safe in the clutches of his “Father Below.” Screwtape in fact would expertly model himself upon his master, the “father of lies,” also known as “Our Father Below.”

As the book idea developed, C. S. Lewis made the connection between the traditional conflict of good and evil and the imagery of modern warfare, with its terror, apocalyptic weapons and global reach. Lewis had lived through World War I and experienced trench warfare on its front line in France. Some of Lewis’s most popular writings on the forces of evil and goodness came into existence in the second global war, with its even more advanced modern weapons of terror.

As Hitler’s broadcast made clear, his story of the racial superiority and heroic destiny of his particular nation was compelling to millions of ordinary, contemporary people, despite being a vicious cocktail of lies. While he was listening to it, Lewis felt himself being drawn into its devilish spell. He confessed to Warnie in that letter, which he started writing on the day after the broadcast, “I don’t know if I’m weaker than other people but it is a positive revelation to me how while the speech lasts it is impossible not to waver just a little. I should be useless as a schoolmaster or a policeman.”2

Lewis evidently pondered how Hitler’s deceptive story, with its carefully crafted plausibility, revealed new things about the ancient nature of evil. The egotistical and self-absorbed leader of Germany fitted well into his own theory of “chronological snobbery.” Lewis had been disillusioned with this attitude in the 1920s through the influence of his friend Owen Barfield. Chronological snobbery was his name given to the all-pervasive belief that the modern view of x is inevitably superior to past ways of seeing x. Older views, to the modern, simply had been left behind by progress.

Then there was the larger vista of war itself, made even more ghastly in its modern forms, such as the present war. World War I had been renamed from “The Great War” because of its total reach. The new war (at that time Lewis called it “the European war”) had already dramatically reached in its destruction and desolation more deeply into cities. The new scale of the bombing of civilians made the attacks by zeppelins in World War I tiny in comparison. Lewis’s thoughts at this time are not recorded, but their outcome in The Screwtape Letters suggest ruminations along these lines in his imagery of hell as a mix of bureaucracy and techniques that might be found in a ruthlessly pragmatic modern business. Tolkien’s own similar thoughts, recorded in letters, reveal concerns about the triumph of machinery as a devilish power (“the weapons of Sauron”) in World War II. As the Screwtape idea increasingly took flight, Lewis shows evidence of thinking about what modern warfare revealed about the age-old battle for the human soul. In Lewis’s humble church in Headington Quarry, in a tranquil Oxford suburb, the talk often was, as it had been for centuries, of a cosmic battle against the world, the flesh and the devil.3 This tradition of such talk had a powerful reality for Lewis as he responded by standing, sitting and kneeling during the liturgy of that July morning service of Holy Communion, a service as familiar to him as his old slippers waiting for him at home.

The years when Lewis lived through World War I and then World War II provide startling insight into his preoccupation with devilry—the powers of evil—and goodness. His differing experience of the global wars, both unprecedented in history before the twentieth century, represent a quest and a growth in Lewis as thinker, writer and storyteller—and as a person. It now seems natural to us for a book like The Screwtape Letters to be begotten during a war that is to us a typically modern, all-out conflict. Many wars now seem to be, in words now common to brave journalists at the scene, “of biblical proportions” or “apocalyptic.” What remains surprising, indeed remarkable, is that Lewis, seemingly without effort, could approach his subject with humor and biting satire, without alienating his readers even today by diminishing the horror of evil and human suffering.

We therefore need initially to explore the context of Lewis’s preoccupation with devilry in the two global, technologically advanced wars that touched his life irrevocably—both conflicts never before suffered by so many people at once in human history and both revealingly characteristic of our era (an era Lewis was to call the “Age of the Machine”).

The Shadow of War

C. S. Lewis, or “Jack,” as friends and family knew him, was only fifteen when World War I began in August 1914 and the world changed forever. He was to reach the trenches of northern France around his nineteenth birthday. During this period of adolescence he was a convinced atheist of sorts, tending at first to be a rather solitary, self-contained person.4 He had no mother, having lost her to cancer before he was ten. Mainly he confided in his brother, Warnie, two years his elder, but saw little of him during these years due first to the separation of schooling and then to Warnie’s service with the British army. He, like his brother, found it difficult if not impossible to find an affinity with his father. He did however find a soulmate in Arthur Greeves, a boy three years his senior who lived very near him on an opulent fringe of Belfast. Lewis corresponded with Arthur throughout the World War I years and, indeed, until his death in 1963, the letters providing insight into Lewis’s life, development and particularly his early thinking. Arthur, a gifted painter, shared a similar taste in reading and all things “northern,” such as Old Norse mythology.

C. S. Lewis, privately educated and from a privileged upper-middle-class background, turned eighteen near the end of 1916. The path he saw before him then was one of very basic and brief officer training as part of student life at Oxford University and then being sent into battle. His prospects of survival did not look good. During the First World War one out of every eight men drawn into the conflict from Britain died.5 Recruits from Oxford and Cambridge Universities, along with others from Britain’s social elite, had a very much higher death rate than the average recruit. This is because most became junior officers and led assaults and operations against the enemy, making them particularly vulnerable.6 The experience of war was to mold his basic ideas about the nature of the universe and inspire a central theme of his writings, which was that of a cosmic war against evil forming a larger context for human battles, whether strife within the individual human soul or bloody conflicts between states.

The “Great Knock”

It was impossible for the young Lewis not to be touched by the conflict, even though he did not train for and then embark for war until 1917, the year before it ended. Most immediately for him, his older brother, Warren, also his friend and confidant, entered the war early on and periodically returned from France on leave. At the beginning of the war Lewis was in the English West Midlands at Malvern College, Worcestershire,7 and miserable, a state that was to decide his father, Albert, to put him under the tutorage of William T. Kirkpatrick, the “Great Knock.” Kirkpatrick, who lived in the village of Bookham, in Surrey, England,8 was Lewis’s tutor from 1914–1917 and nicknamed by him “the Great Knock” because of the impact of his stringent logical mind on the teenager.

Shortly after August 4, 1914, when Germany invaded Belgium and Britain declared war, the British Expeditionary Force landed in France, which Britain had promised to defend. The following month, Lewis began his studies with Kirkpatrick. Near the end of that month, on September 30, Warren, his brother, was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps. Lewis’s rural haven was not unaffected by events. He noted in a letter to Albert, his father, that “war fever” was raging around the Bookham neighborhood. Soon the village people prepared a cottage for Belgian refugees—with the rapid German push into Belgium tens of thousands of refugees had poured into England.

In early summer 1915 there was the first German zeppelin air attack on nearby London. When the airships bombed Waterloo Railway Station, electric flashes in the skies as a result of the explosions could be seen from Bookham. At least, that was what the locals said it was.9 This must have brought home to Lewis the reality and threats of modern warfare.

It is clear that Lewis was continually aware of events of war, particularly in France. France for him was not an abstract concept; he and Warren had shared a memorable holiday with their mother, Flora, in 1907 (the year before she died of cancer), in a French coastal town not far from some of the places made familiar by the war. The conflict however failed to erode his deep happiness under the tutorage of Kirkpatrick. For the last part of 1916 Lewis’s thoughts and anxieties were focused on passing the entrance exam for Oxford University. For him everything was at stake, as he saw no alternative to an academic career, and it also provided a good entry into officer training, after establishing a future place in an academic career. In December 1916 Lewis accordingly made his first trip to Oxford to take a scholarship examination. This took place between December 5 and 9. Passed over by New College, he received a classical scholarship to University College, Oxford. A few days later the London Times newspaper listed among the successful candidates “Clive S. Lewis, University College.” By that time, Britain had been at war with Germany for nearly two and a half years.

Oxford

In March 1917, Lewis came into residence at University College, in the Trinity or summer term.10 This allowed him to start his passage into the army by way of the University Officers’ Training Corps. He was officially a student without requirements of formal studies. Despite evidence of the impact of war everywhere Lewis had a pleasant time. He enjoyed the library of the Oxford Union, punting on the River Cherwell or swimming in it. He was very much aware of the general absence of undergraduates in Oxford, and other marks of war in the unusually quiet town. Most of his college building was taken up with serving as an army hospital.

Cadet C. S. Lewis, Keble College

Lewis was assigned a battalion encamped at Keble College, and was able to keep in contact with new acquaintances at University College. It also allowed a life-changing encounter. The alphabet dictated that his roommate was fellow Irishman Edward “Paddy” Moore, a seemingly trivial fact. As an L, Lewis was placed in a bare, tiny room with the M, Moore. Paddy was the son of Mrs. Janie Moore, who had left an unhappy marriage and Ireland in 1907 to live in Bristol with Paddy and his young sister, Maureen. With Paddy’s commission, Mrs. Moore and Maureen moved to Oxford to be near him. She and Lewis first met in June that year, along with others of Paddy’s friends. Drawn to the Moore family, Lewis spent more and more time in their company. Maureen, who was eleven at the time, remembered, “Before my brother went out to the trenches in France he asked C. S. Lewis, . . . ‘If I don’t come back, would you look after my mother and my little sister?’”11 Mrs. Moore and Maureen were staying in temporary rooms in Wellington Square, not far from Keble College.

Paddy was one of a set of six in their portion of the college. In a letter Lewis described the group as “public school men and varsity [university] men.”12 A look a few months forward to the future reveals the cost of the war. Lewis was to fight with the infantry and to be badly wounded. Paddy Moore was to serve with the 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, dying at Pargny, France, in March 1918. Martin Ashworth Somerville was to battle in Egypt and Palestine with the Rifle Brigade, dying in Palestine in September 1918. Alexander Gordon Sutton was to fight with Paddy Moore in the Rifle Brigade and to be killed two months before Paddy. Thomas Kerrison Davy, with the 1st Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, was to be severely wounded near Arras, where Lewis was to fight, in March 1918, dying later. Denis Howard de Pass was to serve with the 12th Battalion of the Rifle Brigade and was reported “wounded and missing” in April 1918. He was given up as dead, but in fact was captured by the enemy, surviving to fight again in World War II.

As the time for active service loomed larger, training became more feverish. Lewis was given a temporary commission in September 1917 as a second lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry. Within two months he would be at the front lines in northern France.

After a brief home visit on leave to Belfast, he joined his new regiment at Crownhill, near Plymouth, South Devon. Here he became friends with Laurence Johnson, who had been commissioned just months before him, and like him had been elected to an Oxford College. His new friend was very soon to die in France.13 Johnson seems to have encouraged him to pursue philosophy.14 Lewis told Arthur Greeves in a letter that philosophy, particularly metaphysics, was his “great find” at the moment.15

To the Front Lines of France

Just under a month after the visit to his father, Lewis suddenly was ordered to go to the front, being allowed only a forty-eight-hour leave. Unable to visit his father again in Ireland within that time, Lewis decided to spend it with Mrs. Moore and Maureen in Bristol, which happened to be on the way back from Plymouth to his departure point for France, desperately telegramming his father to rush to Bristol to see him: “HAVE ARRIVED BRISTOL ON 48 HOURS LEAVE. REPORT SOUTHAMPTON SATURDAY. CAN YOU COME BRISTOL. IF SO MEET AT STATION. . . . JACKS.” Confused, Albert Lewis simply wired back: “DON’T UNDERSTAND TELEGRAM. PLEASE WRITE.” Thus Lewis did not see his father again until after he was invalided out of France the following spring.

Lewis reported to Southampton harbor at 4 p.m. on November 17, 1917, and crossed to France, to a base camp at Monchy-le-Preux, a place which later inspired one of his war poems, “French Nocturne.”16 By his nineteenth birthday, November 29, Lewis found himself at the front line and introduced to life in the trenches. His brother was elsewhere in France and in a safer location.

In mid-December 1917 Lewis was billeted in the French town of Arras. Though it bore the wounds of three and a half years of war, it would be disfigured even more the following March, when the enemy thrust forward in their last major offensive. Lewis and his colleagues were transported to and from the trenches in buses.17 Before Christmas, Lewis was back up in the cold, wet trenches for a few days, some distance from the main battle lines.

Trench life was not as tolerable as Lewis’s letters home to his father suggested, because by the end of January or beginning of February, Lewis was hospitalized for three weeks at Le Tréport, miles away from the front line, with trench fever or, more technically, PUO (pyrexia of unknown origin).

The Battle of Hazebrouck

It was not until the end of February that Lewis rejoined his battalion at Fampoux, a village to the west of Arras. He was now in the direct line of the final German large-scale attack of the war on the Western Front. Soon he had to spend a whole night digging, in anticipation of the German advance southward. All hell broke loose a little over two weeks later, on March 21, 1918. In the early hours of that morning, German general Erich Ludendorff launched an offensive designed to sweep the allied forces off the Western Front and to open the way for the capture of Paris. The initial softening-up bombardment lasted five hours.

A few days into the battle, elsewhere along the front, at Pargny, Paddy Moore was fighting with his 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, resisting the massive German offensive. He was last seen alive the morning of Sunday, March 24. His remains were taken up and buried in a field.18 Mrs. Moore later was informed that he died from a bullet to the head as he was receiving emergency treatment for a wound. When this was happening, Lewis’s battalion was being moved around the battlefront near Arras.

Between April 12 and 15, still in the area north of Arras, quite near the Belgian border, Lewis was caught up in the Battle of Hazebrouck. The action he saw took place around the village of Riez du Vinage. During the battle, much to his surprise, he took sixty retreating German prisoners who were eager to surrender. He was wounded on Monday April 15 by “friendly fire” at Mont-Bernenchon, a slightly elevated hamlet just southwest of Riez du Vinage. At least one British shell burst close by him, killing his friend Harry Ayres and fatally wounding Laurence Johnson, who were standing with him. Shards from the shell ripped into Lewis’s body in three places, including his chest. Lewis then began to crawl back over the cold mud toward help and was picked up by a stretcher bearer. Within a couple of days Albert in Belfast received a telegram from the War Office: “2ND. LT. C. S. LEWIS SOMERSET LIGHT INFANTRY WOUNDED APRIL FIFTEENTH.”19 Pieces of shrapnel remained in his chest for much of his life.

Warren, stationed at Doullens, heard from Albert Lewis that his brother was wounded and hospitalized at Etaples (south of Boulogne, on the French coast). He borrowed a motorcycle and found his way the fifty miles west to the coastal hospital. Warnie was seized by anxiety as he drove. His fear turned to thankfulness and joy when he came across “Jacks” sitting up in bed. Though serious, Warren found, the wounds were not life-threatening.

From the Liverpool Merchants Mobile Hospital at Etaples, a few days later, Lewis wrote to his father that he had been hit in the back of the left hand, on the left leg a little above the knee and in the left side under the armpit. Army medical records recorded, “Foreign body still present in chest, removal not contemplated—there is no danger to nerve or bone in other wounds.”20

In the mobile hospital in Etaples, Lewis worked at understanding his hellish experience in the light of his atheistic beliefs. He sought to retain a place for beauty and the spirit in his materialist worldview (that is, the view that nature is the whole show—there is nothing outside it).21 He thought about the “lusts of the flesh,” which so often buffeted him. He had found himself to become almost monastic about them. This is because, he reasoned, fleshly desires increased the mastery of matter over the human spirit. On the battlefield, and in the hospital among the casualties of war, he saw spirit constantly evading matter—evading bullets, artillery shells, and driven by the sheer animal fears and pains that wrack human beings. He saw the equation starkly now as matter equals nature, equals Satan. The only nonnatural, nonmaterial thing that he discovered was beauty. Beauty was the only spiritual thing he could find. It was beauty versus nature, beauty versus Satan. Nature was a prison house from which only humans were capable of escape, through their spiritual side. There was however no God to aid them. It was a materialist’s mysticism. It might seem odd to say this, but, in fact, in his mystical concerns as an avowed atheist, Lewis anticipated a feature of spirituality now commonplace in the West. With the increased influence, for instance, of Eastern thought, it has become clear that mysticisms have long existed outside of theistic beliefs—that is, beliefs in a God responsible for the existence of the universe, as found in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The nontheistic mysticisms are found in Hinduism, Buddhism and many other beliefs.22

A poem called “Satan Speaks,” from Lewis’s volume of poetry composed in the war years, Spirits in Bondage, vividly portrays his atheist beliefs at this time:

I am the battle’s filth and strain,

I am the widow’s empty pain.

. . .

I am the fact and the crushing reason

To thwart your fantasy’s new-born treason.23

Recovery and Convalescence

Lewis was transported in May 1918 to the Endsleigh Palace Hospital in central London. He was pleased to find this a comfortable place, where he even had a separate room. He was also happily aware of the fact that he could easily order from the many bookshops nearby.

Lewis arranged to continue his convalescence in Bristol, to be near Mrs. Moore and Maureen, being moved there near the end of June. His recovery was slower than anticipated—he remained in Bristol until mid-October. While in Bristol, Lewis was able to report some good news to his Ulster friend Arthur Greeves. After keeping his slim typescript of poetry for what seemed to him a considerable time, William Heinemann had accepted it for publication. Lewis told Arthur that it would be called Spirits in Prison, and that it was weaved around his belief that nature is a prison house and satanic. The spiritual—and God, should he exist—oppose “the cosmic arrangement.” The book was eventually published under the revised title of Spirits in Bondage in March 1919, when Lewis was twenty.

Though war ended on November 11, 1918, Lewis was still on active service. Two days before Christmas, Warren arrived home in Belfast on leave. He believed that he would not see his brother, who was still at a military camp. But late on December 27 he recorded in his diary the unexpected arrival of Jack: “A red letter day. We were sitting in the study about eleven o’clock this morning when we saw a cab coming up the avenue.” His brother had been demobilized.24

Another War, A Different C. S. Lewis

“My memories of the last war haunted my dreams for years.” Lewis disclosed this in a letter over twenty years later, on May 8, 1939. War had become for him a deeply embedded image of a grimly persistent cosmic war between good and evil. In a sermon, “Learning in War-Time,” written soon after the start of the new world war, he observed, “War creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it.”25 During the years of the First World War and immediately after it, the struggle for him was conceived in terms of a battle between nature and spirit, with nature being evil unless touched by beauty and spirit. Bluntly, nature was Satan, the devil. After Lewis’s conversion to theism around the end of the 1920s and to Christian belief in 1931, he accepted an orthodox (or, as he was fond of saying, a “mere”) Christian view of the essential goodness of nature, in which evil is a despoiling and absence of good. Nature was spoiled, not evil in essence. Furthermore evil damaged both nature and spirit, with the origin of evil lying in our human freedom to rebel against God, rather than in nature itself. Lewis’s war experience effectively became part of his inner life, first as a materialistic vision of the war of nature and spirit, and then as a cosmic battle between good and evil in Jewish-Christian terms. Lewis, even as an atheist, never indulged in the fashionable literary spirit of disillusionment after World War I. There was no fundamental mismatch between his beliefs and the horrors of his wartime experience.26

The start of the Second World War on Sunday, September 3, 1939, therefore found a C. S. Lewis who in many ways was different from the young man who tried to turn his experience of war into poetry. He had become a Christian just eight years before, after a long conversation with his friends J. R. R. Tolkien and “Hugo” Dyson and many conversations before that with Tolkien and also Barfield. His wide reading of Christian writers such as G. K. Chesterton, James Balfour and George MacDonald (not to mention seventeenth-century English poets) also played an important part. He increasingly valued his friends. Since becoming a Fellow and Tutor of Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1925, he had joined university clubs and surrounded himself with them. One group of friends who were inclined to write became around 1933 a literary club dubbed “the Inklings,” of which Lewis was the life and soul and natural leader.27 It took its name perhaps in the fall of that year, some months after Lewis published his first fiction, The Pilgrim’s Regress. By then he and Tolkien had shared with each other manuscripts they were writing, and this habit carried over into the Inklings’ meetings. Before the Inklings took shape Lewis already had been among the first to read an emerging draft of what became The Hobbit (not published until 1937). Tolkien subsequently read at least some of the book to the Inklings. In that book, evil is portrayed by a traditional dragon straight out of Old Norse mythology—its darker representation as a crafted ring is only in seed form. There is, however, in the background, the shadowy figure of the Necromancer, who is revealed in the later sequel The Lord of the Rings to be Sauron, the Dark Lord.