Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Before It Went Rotten takes a trip back to the world before punk. When Anarchy in the UK appeared, London enjoyed one of the most vibrant music scenes in the world. A network of mainly Irish owned pubs and clubs provided music every night, much of it free of charge, whilst working as a testing ground for up and coming talent. This book traces the evolution of what was quickly labelled 'pub-rock': from rock and roll revival acts via late blues bands, country rock, funk, soul and art school bands to the sound that eventually burst on the scene as punk rock in 1976. Specific chapters cover the career of Brinsley Schwarz, the Southend bands and the step by step rise of the Sex Pistols. Among those interviewed are former members of Fumble, Darts, the John Dummer Blues Band, Blue Goose, Legend, Eddie and the Hot Rods, Brinsley Schwarz, Bees Make Honey, Ducks de Luxe, Kokomo, Roogalator, Burlesque, Kilburn and the High Roads, GT Moore and the Reggae Guitars, Clancy, the Fabulous Poodles, the Sex Pistols and Meal Ticket. With acts like Dire Straits, Elvis Costello, Ian Dury and Graham Parker all emerging from this terrain, the reader is asked to consider, what, if anything, would have been different if McLaren's band had never been around. Extensively researched, and drawing on contemporaneous reviews and articles from the music press of the time, Before It Went Rotten bids fair to be the definitive study of an overlooked era.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 584

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

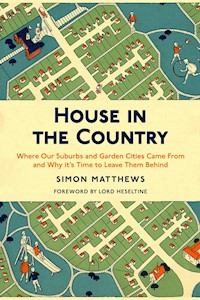

Praise for Simon Matthews

‘Psychedelic Celluloid covers the swinging sixties in minute detail, noting the influence of pop on hundreds of productions’ – Independent

‘Addresses everything with a thoroughness and eye for detail that’s hugely impressive’ – Irish News

‘The ultimate catalogue of musical references in film and TV from the swinging sixties’ – Glass Magazine

‘Impressively comprehensive... positively jam-packed full of trivia and amusing anecdotes’ – We Are Cult

‘A must-purchase for fans of British films and pop music’ – Goldmine

‘For anyone with a love of the music, fashions, and the scene, or for anyone who simply adores movies, Psychedelic Celluloid is a handy book to own’ – Severed Cinema

INTRODUCTION

This book was commissioned by Ion Mills, publisher and owner of Oldcastle Books, after the publication of Looking For a New England in early 2021. Thanks, therefore, are due to him for initiating the project, and to his team in assisting in its production. He suggested something that looked at the music that emerged from the London pub-rock scene of the mid-70s. Traditionally seen as the poor relation to the glamorous era of the 60s, and the punk rebelliousness that came a few years later, the pub-rock period is actually the thread that connects them, a time when ideas (and careers) germinated.

So, this is a book about that. What it is not is a book about guitar solos, amplifiers, drum kits and well-honed anecdotes. There are plenty of other accounts that deal with these. Instead, it tries to tell the story of the musicians, as they worked within the day-to-day circumstances of that time.

Some disclaimers are needed.

Firstly, throughout the book reference is made to whether or not records sold, and if they did, their chart placings are given. We need to be clear that at that time many of the independent record shops that stocked singles and albums by ‘pub-rock’ and related bands were not ‘chart return shops’. However many copies they sold of a release by, say, Ducks Deluxe, they counted for nothing in assessing whether that record should be placed in the UK Top 30, or Top 50. The majority of ‘chart return shops’ were long-established High Street businesses, branches of Woolworths or the record-selling sections of department stores, and it was data compiled every week from these staid outlets that produced the Top 30 listings of that time. It is possible, therefore, that some ‘pub-rock’ records outsold material that was listed in the charts, without ever featuring in their own right. Trying to reassess this now, though, would be an immense task and like music industry insiders then I opted to go with what would have been relied on at that time.

Secondly, however one defines it, ‘pub-rock’ was very much a minority interest. This was a time when the music papers reviewed 25-30 singles each week, up to 150 a month; and this was just their selection of what was available. As can be seen in the discography at the back of the book, ‘pub-rock’ and related releases ran at 5-10 a month at best, and in some months none at all. Even towards the end of this period, in 1975-76, they accounted for no more than 5% of what was being written about. There can’t have been more than 20,000 young people in the UK actively interested in this scene, out of a total population, in the 15-25 age bracket, of around 7 million. It’s important to remember, therefore, that the artistes described in this book were pioneers, operating mainly without reward and drawing their inspiration from sources that the majority of those interested in music either rejected or found baffling. And yet… this is the motherlode that people keep returning to, the dynamo that powered the cultural and musical changes that occurred post-1976.

Thirdly, I am aware that this is a white male perspective. The pub-rock scene featured only a few black musicians, and fewer women. The passage of time has depleted their numbers further and despite making every effort to contact those who survive, I drew a blank. This is a matter of regret as their perspectives would have been welcome, particularly for the insights that they provided on the social mores of the time. Given these circumstances I have had to rely on comments and accounts from them that are already published, rather than fresh primary material.

Finally, wherever possible all the sources quoted are referenced in the text. Occasionally a lack of sources (or individuals who can corroborate events) has meant that some assumptions have had to be made. I should add that historian Alwyn Turner made available his personal archive of ZigZag magazines, from which much was gleaned, and for which I am grateful.

My thanks are due to the following who helped piece this account together, by telephone, email and one-to-one interviews or just by facilitating contact with others: Michael Harty, Chris Birkin, Frank McAweaney, Sean MacBride, Peter Buck, Pete Lockwood, Carl Matthews, Bobby Valentino, Mark Howarth, Billy Jenkins, Patrick Hickey, Glen Matlock, Kevin Burke, Des Henly, Horace Trubridge, Nick Hogarth, Charlie Hart, Dave Kelly, Gerald Moore, Mo Witham, Danny Adler, Paul Gray, Tony O’Malley, Deke O’Brien, Colin Bass, Rod Demick, Chris Money, Billy Rankin, John Greene, Ian Gomm, Martin Belmont, Lyndon Needs, Alan Hooper, Tim Hickey, Ed Lukasiewicz and Duncan McKenzie.

Simon Matthews

Sligo, 2022

ONE NIGHT IN 1974

It was a Friday afternoon in October. The clock said 2.38pm. He sat at his small battered desk on the second floor of the GLC Regional Housing Office, King’s Cross Road, London WC1. A few other people worked away, barely talking, telephones occasionally ringing, amidst a haze of cigarette smoke. He was preparing a mail out, targeted at waiting list applicants. In a fortnight they were letting 50 spare flats across Hornsey and Archway, some brand new but a bit odd, including a dozen bedsits in a new tower block; others were ‘hard’, unmodernised and old in tenements; some above shops or peculiar multi-floor arrangements within a house. His job as a Lettings Officer was to get armfuls of housing applications out of the banks of filing cabinets where they were kept, check the date of last contact, and send whoever it was a pro-forma letter asking them to confirm attendance on a specific date, at a specific time, so they could be offered one of the properties. He’d worked on it for two days, gradually piling up the documents on a small table next to the franking machine and photocopier, clearing a space on his desk between the chipped grey telephone and the well-thumbed A-Z. Like many of his colleagues a street map of Islington and Camden was fixed on the wall behind his desk, next to an old, badly torn, Tube map, and yellowing plans of key estates. His job was to reach a hundred. He was nearly there. Once that was done it was simple; you wrote the name and address of the applicant in pen on the letter, put the signature of the Area Housing Manager on the bottom, (using a rubber stamp that had to be constantly replenished via an inking pad), sealed it in an envelope and ran it through the franking machine.

Just after 3pm one of the Housing Assistants came around, handing out pay slips. His went straight to the bank but a few of the others still wanted cash in an envelope. He glanced at his monthly statement; no surprises. It amounted, as it always did, to £34 a week reducing to £٢٢ after tax, pension, Trade Union and National Insurance deductions. It wasn’t fantastic, but it was enough to live on and even save a little. By 4pm he had finished addressing, signing and enveloping the hundred letters, and had also left a copy of each on every file. He made himself a mug of tea in the airless, windowless cubicle where they had a kettle, sink, fridge and permanently untidy larder. Then, one by one, he pushed the envelopes through the franking machine, collected them into an oozing, brown mass and strapped a thick rubber band around them. He sat, drank the tea, and then carried the package past the manager’s office and left it with the elderly porter on the ground floor who dealt with the post collection every evening.

He left at 5pm. It was raining, windy, overcast and noisy. He waited for the 239 bus at the crowded stop outside King’s Cross Station. It was cheaper than getting the Tube. None came for 20 minutes, then three together. It was easy to pick them out; they were single-deck, one-person operated unlike the stream of double-deckers that slowly circulated and dispersed. The first ignored the crowd and sped past, empty. He chose the second, running quickly to catch it and sitting at the back, surrounded by steamed-up windows, next to an old man with an immense bronchial cough. The bus moved slowly in heavy traffic along York Way and paused by the railway goods yards where an engine was being marshalled onto a long line of parcels vans, the guard walking slowly back, swinging a paraffin tail lamp. They passed scrapyards, garages and gloomy industrial buildings, and then stopped for almost five minutes by the new estate being built at Maiden Lane. At Camden Road the cafés were closing and the kebab shops getting ready for an evening’s business. The stuccoed Georgian and early Victorian properties were coming back to life, as they always did, however battered they were, lights clicking on in selected windows, and the bus slowly emptied. He got off just before Tufnell Park and walked down Corinne Road to the house where he lived.

It was on the corner where the road bent north, and his room was upstairs, at the front with a fine bay window. He unlocked the door, turned on the light, closed the window and pulled the curtains across. He had a decent amount of space. A low-slung double bed (a mattress on an improvised wooden frame) in one corner. A tall chest of drawers diagonally opposite. A 50s Bush radio next to the bed. A record player opposite, on a tiny table next to the chest of drawers, with his album collection leaning in a neat parade against the table legs. There was a small electric fire in the fireplace, next to which, positioned at a homely angle, was an old armchair he had bought at a jumble sale for 50p. The floor was covered with grey-green carpet squares with a faux oriental rug in the centre. Improvised bookshelves ran up the main wall, crammed with an immense number of paperback books. He hung his jacket behind the door, collected a frying pan from the wooden cutlery and crockery box beneath the chest of drawers, opened the lower drawer (his larder), took out a packet of sausages, some bread and butter and went downstairs to the kitchen.

Adelaide, the young black woman who collected the rent for the co-op, was cooking a pot of vegetables. She was in her dressing gown with her hair piled up in a turban. They exchanged greetings and he waited while she finished preparing her meal. She manoeuvred past him and went back to her room, taking her pot with her. He made a cup of tea and a sausage sandwich. Then, he sat in the corner by the sink, opened that week’s copy of Sounds and began reading, drinking and eating.

Finished, he knocked on the door of the downstairs front room where his friend Kevin lived. A young Irishman with unruly black hair and blue eyes, Kevin worked during the day for two older Irishmen who owned a removal van. He started and finished early. They spoke, agreed to go out at 7pm. He went back upstairs and had a wash in the bathroom on the landing. He hardly ever used the bath. They had an Ascot, but the water it trickled out was never sufficient or warm enough, except on the hottest of summer evenings. In his room he changed into jeans, t-shirt, bomber jacket, Dr Martens and a scarf. He put a £5 note in his wallet and met Kevin in the hallway. Outside it was still windy, scraps of rubbish had been blown up and about, far into the night, accelerated by the passing traffic. They walked to the Boston Arms.

Kevin rolled a cigarette and they drank Guinness. Where’s Amanda he asked, referring to Kevin’s girlfriend, who worked as a temp at the BBC. She’s away, said Kevin, vaguely. At the end of the long wooden saloon, covered in brown panelling and heavily embossed scarlet wallpaper, a trio of men played pool beneath a huge colour picture of the triumphant Kilkenny hurling team. Tammy Wynette played on the jukebox. What’s up tonight, asked Kevin. Scarecrow are on at The Lord Nelson he said. Should be decent. They drank up and outside saw the 4 bus, ran alongside it and jumped on the platform as it slowed by the lights. They sat in the deserted upper saloon all the way to Holloway Road without being asked for their fares. Here they changed again, stepping off outside The Lord Nelson. Seems quiet, said Kevin. He went to the bar and asked. No, they’re tomorrow night now, said the barman, it’s a party with donations instead. Kevin and he took a look inside the main stage area. There were posters up advertising a benefit gig for Chilean refugees, organised by the DHSS Archway branch of NALGO, with folk singers, leaflets, papers and two speakers. It doesn’t appeal and they discuss their options. We could try Charlie and The Wide Boys at the Carousel, he says. Kevin shakes his head. No, it’d be expensive and start late. I need to be up early in the morning.

They catch another bus on Holloway Road and arrive at the Brecknock. It is 9pm. In the stage area to the side there are about 200 people, mostly young men, watching a band. The walls around the stage are encrusted with posters, stickers, photographs… some care of record companies and agencies, some self-produced. Many are torn and the effect is as if a huge brightly coloured selection of litter and waste paper had been swept up and splattered there by a storm. The band are finishing their first set. The area partially clears. Kevin and he find a table set to one side; they get beer and bags of nuts. They are opposite two young women. He asks what they think of the band. Really good, says one, but a bit loud. The other, with cropped ginger hair, looks superciliously at them and smokes. You don’t like it then? Kevin asks aggressively. They talk disjointedly above the sound of the jukebox.

The band start another set. They’re a six-piece with vocals, saxophone, keyboards, guitar, bass and drums. Kevin and he get up and watch, standing in a closely packed throng just in front of the slightly raised stage. They’re not bad, he says. A couple of numbers in there is an altercation behind them. Some pushing and shoving. Somebody shouts play something proper. What, like you, says the singer. Another couple of numbers pass, then a glass flies through the air splintering against the rear wall. The band duck, the crowd parts and the doorman, a wrestler employed on music nights by the landlord, gets the offender, a thin, unshaven man in his late 30s in a headlock, dragging him out and propelling him into the street. Woah, everybody ok, asks the singer. The drummer pushes the remains of the glass away with his boot. They launch quickly into Route 66 followed by I’m A Believer and then one of their own, a country-rock singalong about hitchhiking home from college. The frisson passes.

He goes to the bar to get two more beers. The woman with cropped red hair is there. They talk again, noise permitting. She seems friendly and writes down her sister’s phone number on his hand with a biro borrowed from the barman. I live up in Muswell Hill, she says. He finds Kevin. The band finish their set with Waiting For My Man. The crowd disperses. They drink up and leave. The two women are just ahead of them. The one he spoke with waves faintly to him and they walk on into the night. Couple of sixth formers, I reckon, says Kevin dismissively. Probably, he says. They cross the road to a crowded kebab shop. Outside the pub the excluded man has come back. He accosts the doorman, who pushes him away again. He stumbles back against a low boundary wall, picks up a discarded half-brick and throws it in the direction of the doorman. It misses, and hits the ex-GPO van that the band are loading their gear into. A fight starts. The guitarist in the group kicks the man who reels back with a massive nosebleed. A passing police car stops and four policemen emerge, walking towards the pub. Come on, let’s go, says Kevin. They leave the kebab shop and walk back, past the darkened houses, the flats above shops and the council blocks.

At the house he fetches a jar of brown rice and a small tin of Chinese fish curry from his larder, cooking them in the kitchen. Adelaide comes in to make some tea. I’ll pay my rent in the morning, he says. You should come to the next co-op meeting, she says. We’re discussing whether to put it up to £7.50; you’d be good at it, working for the GLC. None of the others knows what they’re talking about. I might, he says, and eats his curry. She goes back to her room and he drinks more tea.

Upstairs, he locks the door and lets in cold air through the window. He tries to find Radio Caroline, but settles instead for the BBC World Service. Whilst the midnight news is narrated like a sacred prayer, he transfers the phone number from his hand to a scrap of paper, putting it in his wallet. In bed, he thinks about Saturday. He has options. Record shops. Clothes shops. Maybe Swanky Modes. Or a jumble sale. He falls asleep as faintly, in the hall below, Kevin talks quietly into the payphone. In the night an ambulance passes, on its way to the Whittington Hospital.

THE PUBS

Our fictional narrator lived in a different world, and one that has now largely gone. Like anyone, then and now, he would have taken his immediate surroundings as being part of a reasonably fixed continuum. An environment that was, perhaps, a bit different from the recent past, but still recognisable to people who had been around a decade or two earlier. This was certainly true with regards to watching live music in pubs.

If he and his Irish friend had ventured forth the week that they sat their O Levels in May 1971 they could have seen Alex Harvey, doing a vigorous jazz-rock set with Rock Workshop at The Green Man, Great Portland Street, or folk guitarist Martin Carthy at The Roebuck, Tottenham Court Road. Elsewhere, central London was replete with colleges, universities and cinemas providing live music alongside more established venues like the Marquee, the Lyceum or the Roundhouse. (The latter admittedly a recent interloper.) Pubs in Camden, Islington and Hackney were conspicuous by their absence, being deemed, for the most part, either too small or too rough to function as effective venues.

But there were outliers. The Greyhound, 175-177 Fulham Palace Road, London W6, offered rock bands five or six nights a week with the likes of Brewers Droop, Amazing Blondel and Gnidrolog all performing there in May 1971. Admission was free. In the 60s The Greyhound had been a respected Irish music venue, featuring the likes of fiddle player Jimmy Power, whose contributions to the 1967 LP Paddy in the Smoke: Irish Dance Music from a London Pub were ‘recorded during the ordinary Sunday morning sessions at one of the many London pubs embellished by Irish musicians’.(1) From there it transitioned to being a folk club, showcasing artists like The Young Tradition, Shirley Collins and Dave and Toni Arthur. By 1970, under landlord (and former boxer) Duncan Ferguson, it was a rock venue, and would remain so throughout this period. But not one without dangers to the visiting music enthusiast. As one punter remembers, it was ‘run by a hard as nails Glaswegian called Duncan. When I was going there, the crowd would be a mix of Punks, Mod Revivalists, Skinheads and there was still a few “Teddy Boys” knocking around. It would often kick off between the rival factions, and Duncan would instruct his two sons, that worked behind the bar, to “Sort it oot”; they had long hair and wore flared trousers, and would leap over the bar, roll up their sleeves and have a punch up, they never ever called the police!’ (2)

The mention of flared trousers and long hair seems to date this account to no later than 1976-77. Possibly the earlier years were a bit less combustible? It’s hard to imagine anyone brawling at a Gnidrolog gig. On the other hand, other punters recall The Greyhound as being ‘a well-known venue with bands playing most nights, owned by a Scottish guy called Duncan Ferguson who was a bit of a ruffian, and hung out with the West London footballers’. It also had lunchtime striptease and was where rock singer Frankie Miller lived on occasion, despite having a combatative relationship with Ferguson’s dog. It was a rough place.(3)

Otherwise, inner London boasted little by way of music in pubs, unless you count Tooting as ‘inner’, though in truth many would still have regarded it as respectable and vaguely suburban in 1971. That week saw Savoy Brown at The Castle, 38 Tooting High Street SW17, the back room of which functioned as the Tooting Blues Club. Involved in continual touring to promote their breakthrough Decca LP Looking In, this was home territory for a band that hailed from Battersea.

Some distance across the city, at The Green Man, 190 Plashet Grove E6 you could have watched Egg, an earnest, ‘progressive’ trio, performing material from their second LP The Polite Force, to an audience that sat cross-legged on the floor. A few miles north, at The Red Lion, 640 High Road E11, 50p got you admission to a show by East of Eden, about to hit No 7 in the UK charts with their single Jig-a-Jig. Both venues had a long history of dances and live music, with The Red Lion well known for its large ballroom area.

And finally, spread out across South London, May 1971 offered John Peel favourites The Edgar Broughton Band at the Winning Post, Twickenham, promoting their LP The Edgar Broughton Band; Hawkwind at The Harrow Inn, Abbey Wood (admission 40p); Duffy Power at The Three Tuns, Beckenham; and, incredibly, Funkadelic at The Greyhound, Croydon, on a UK tour with a set culled from their US album Free Your Mind… And Your Ass Will Follow. The Three Tuns, a large mock-Elizabethan pub on Beckenham High Street, was well known as the site of the Beckenham Arts Lab, much associated with David Bowie circa Space Oddity. One imagines that Duffy Power, formerly a coffee bar rocker of some repute, did a similarly introspective turn there. But Hawkwind? In Abbey Wood? This was the band en route for Glastonbury Fayre and gearing up for In Search of Space, featuring new recruit, and dancer, Stacia, a light-show and heavy biker presence. All jammed into The Harrow Inn, about which little survives, other than online comments noting that it was ‘moderately rough’ with one local stating after its closure, ‘I got offered a sawn-off shotgun in there one night.’ Interestingly, it was just down the road from Thamesmead where Stanley Kubrick had only a few weeks earlier completed filming some of the memorably violent scenes in A Clockwork Orange.(4)

Which brings us to The Greyhound, Croydon, the least typical of all these venues. On Park Lane, opposite the Fairfield Halls, it was a modern ground-floor pub built into an office building; a lot of new office blocks appeared in Croydon around this time. The music happened in a set of function rooms immediately above the bar area and went by the name, initially at least, of the Croydon Blues Club. Sundays were a particularly favoured night. With the surrounding premises empty at the weekend and not too many houses in the area, volume wasn’t an issue in the way it could be elsewhere. The music room itself was a good size, with a decent stage, and no furniture, but in a major early 70s design failure it was carpeted, and in the years that followed approximately a million cigarettes would be stubbed out on it, joined by immense amounts of spilt alcohol mingling with other ominous and unpleasant-looking stains. It must have seemed odd to Funkadelic, coming to Earth in such surroundings. And lively too; the bar had shutters that could be pulled down when fighting began.

This was what was on offer in London’s pubs one week in May 1971. A selection of hopeful names, perennial troupers and major acts. Some of the venues were established within a wider, larger circuit, and had been so for many years. In fact, depending on how far you want to go back, performing music in pubs, either on its own or as part of an evening’s entertainment, was definitely an English tradition. As any student of Victorian music hall will know, many music halls started as pubs, and many pubs, even if they didn’t develop into full-scale variety theatres, offered music hall type ensemble billings, staged in the saloons, ballrooms and back rooms attached to them.

Most of these were clustered around inner London, with a concentration in Camberwell, but few if any survived into the 60s in their original incarnation.(5) Importantly they set a template for how typical pubs should be built: with a room, hall or saloon that could be used for general entertainment purposes. Many examples, hundreds even, of such venues existed across London and most put on dances, comedians and occasional live music, one or more nights a week, through the 50s, 60s and 70s without ever becoming regular ‘music venues’ or advertising in the music press. They formed a kind of secondary or even tertiary layer beneath the variety theatres for many years. A particularly strong locale for this type of entertainment was London’s East End, where there was even a mini-revival of the genre in the early 60s, at places like The Rising Sun, Bow, the Deuragon Arms, Hackney and the Iron Bridge Tavern, Poplar.

Of these the Deuragon needed to be approached with some care.(6) Run by the Kray brothers, it hosted music, satire and drag artistes. The music was normally the type of light jazz singalong standards on offer everywhere, though an early version of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band had a residency at one point. Satire came via comedian Ray Martine, a considerable TV figure in the 60s and 70s, whose live album East End West End was recorded there on New Year’s Eve 1962.(7) Drag was usually by Gaye Travers, whose shows attracted the likes of Noel Coward and Kenneth Williams. the Iron Bridge Tavern was run by actress-singer Queenie Watts, whose film, TV and stage work stretched from Ken Loach’s Poor Cow to Come Together, the latter an extended 1970 Royal Court Theatre revue that included The Alberts and The Ken Campbell Roadshow. Like Martine she released an LP, Queen High, with backing from Stan Tracey on a couple of tracks. Her reputation was such that she also appeared in Joan Littlewood’s Sparrows Can’t Sing, the finale of which takes place in a typical East End pub similar to the one Watts herself ran.

The success of this milieu appealed to Daniel Farson, a broadcaster, writer and Soho habitué of some standing. He purchased The Waterman’s Arms on the Isle of Dogs, converting it, quite extravagantly, into a miniature music hall, hosting performers like Shirley Bassey and drawing an audience that included at various times Francis Bacon, Clint Eastwood, Brian Epstein and Judy Garland. By May 1963 there was an ITV series, Stars and Garters, cashing in on this localised renaissance. Filmed on a stage set modelled on the kind of pub run by Farson or Watts, it was scripted by Marty Feldman and Barry Cryer, presented by Ray Martine and featured Kathy Kirby, a platinum blonde singer who looked an absolute dead-ringer for Marilyn Monroe. None of this was rock and roll, or anything like it. But it did overlap slightly and both Joe Cocker and Dusty Springfield appeared on Stars and Garters during its three-year run. And it was hugely popular.(8)

Anyone who was in a band during the 70s will confirm that venues of this kind still existed then, occasionally putting on a group or singer and reliant on word of mouth, coverage in the local paper or just posters put up outside the venue itself to attract an audience. Considering that, and looking through Melody Maker, New Musical Express, Sounds and Time Out for the period 1972-76, there seems to have been about five different types of music venue: folk clubs, jazz clubs, established pop and rock venues, Stars and Garters-type places (for want of a better description) and traditional Irish clubs and pubs. The latter didn’t advertise much in the music press either, and location-wise were heavily grouped around west and north London. In size they ranged from huge ballrooms like the Gresham, Archway Road, featuring the major show bands, (GLC) to niche places like the Sugawn Kitchen, Balls Pond Road which doubled as a theatre. An awful lot of country and western was performed in them, and some were listed, rather confusingly, under the ‘Folk’ heading in Melody Maker.(9)

Out of this mass of pubs, clubs, bars, ballrooms, backrooms, function rooms, shebeens and saloons, folk venues seem to have been the most common, with roughly as many of them as there were jazz and pop/rock put together. What is clear is that, looking at everything as a whole, there weren’t that many established pop/rock pub venues circa 1971 in the first place and the scene tended to be pretty fluid anyway with some opening as others closed. It clearly stretched some way beyond London too. The East End diaspora into Essex, Hertfordshire, Canvey Island and Southend-on-Sea remained a traditional bastion for music in pubs, albeit the media, then as now, was resolutely London-centric, carrying few advertisements of what was on offer in such locations.

The transient nature of this scene reflected the practicalities landlords faced in running such a venue. The key issues here were obtaining a music licence from either the local council or the Greater London Council (GLC) (which is why so many of these places came and went; licences either expired or were revoked following objections by residents or the police), the length and conditions of the tenancy offered to the landlord by the brewery (which again might not be renewed, or might even be terminated if there were complaints) and, of course, how feasible it was to stage music there on a regular basis. Did it have a music area that could be separated from, and managed separately ‘on the night’ from the main drinking area?

Having jumped through these hoops there was then the question of what kind of crowd you might attract. In folk clubs this wasn’t a problem. Audiences listened in silence and were well behaved. Jazz was a bit noisier, but the punters were usually not too much trouble, tending to be late 20s and older. The days of duffle-coated trad enthusiasts trading blows over the use of a saxophone were long gone. The problem lay with rock venues. Attracting an audience somewhere between 16 and 25 years old, ‘doormen’ were needed to keep order in most places, given the considerable capacity for fighting, brawling and out of control (and underage) drinking, as well as the distribution and consumption of various substances. The bands played at a fair volume too, even if most of them deployed a smaller PA system than would usually be required at the Hammersmith Odeon.

In practice, most landlords either handled the bookings themselves or used some type of agency to do so. The breweries weren’t involved. From their point of view, they granted the tenancy for a fixed period, either by advertising it in The Morning Advertiser or by renewing a lease that had been with a family for generations. Landlords were obliged to buy their beer from the brewery at rates far higher than the open market, so not unnaturally, with rent and staff, including in some cases a manager, to pay they looked to maximise their sales and draw in a crowd. And they had to, given the rapidly changing environment within which they operated. The urban depopulation, and associated redevelopment, that affected London for 40 years after 1945 swept away many pubs, added to which the growth of TV ownership and access to better housing meant that sitting in a saloon bar all evening drinking a pint was no longer the kind of cheap entertainment it had once been. Whether it was staging ersatz music hall like Watts and Farson, or bingo, or comedians, or strippers, every effort had to be made to keep decline at bay and increasingly pubs tried live music as part of their sales pitch to their neighbourhood. They might put on bands one night a week, or every night a week. They might offer residencies or have a constantly changing roster. They might pay a small fee, or split the beer money. But, whichever way they cut it, they had to keep bringing in the customers.(10)

If they didn’t, they would close as music venues, which might happen anyway even if they were successful due to licences being revoked or particular landlords moving on. Such was the fate of Bluesville, 376 Seven Sisters Road N4, the Bag o’ Nails, Kingly Street W1 and Klooks Kleek, The Railway Hotel, West Hampstead in 1970.(11) The Oldfield Tavern, Greenford, the Northcote Arms, Southall, The Toby Jug, Tolworth and The Pied Bull, Liverpool Road N1 all went in 1972 and an attempt by Rank to convert three redundant cinemas, in Brixton, Mile End and Edmonton, into night-time concert halls, appending the name Sundown to their location, failed after only a few months shortly afterwards.

Even after bands and booking agents began venturing into pubs in larger numbers, closures continued at a steady rate. The Tally Ho, Kentish Town and Cooks Ferry Inn, Angel Road, Edmonton, didn’t have live music after 1973, with the latter closing and being demolished a year later when the North Circular Road was widened. The Nightingale, High Road N22 put on nothing after 1974, the same year that the Wake Arms, Epping, aka Groovesville, closed. Both the Tithe Farm House, Harrow and The Village Roundhouse, Dagenham shut in 1975.(12) The latter was exceptionally impressive: an immense purpose-built entertainment venue – pub, bingo hall, function rooms and ballroom with a capacity of 2000 – built as part of the adjoining Becontree Estate. Up until 1969 it operated as The Village Blues Club, putting on bands like Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd and later hosting early UK shows by German acts Faust and Can. But to no avail. After a gig by Sailor on 8 November 1975 a poster appeared stating, ‘We regret that due to objections from the G.L.C. the club will be closed after this Saturday because of complaints from local residents regarding the noise. We hope the club will be ready to reopen very shortly. Please watch Melody Maker for full details of reopening. If you would like to help with a petition please write to the Roundhouse.’ It didn’t reopen.

It’s interesting to note the preponderance of large suburban pubs in this network, and how they withdrew from the market first. Most of their gigs were by commercially successful bands with album deals. The demise of the Wake Arms – sited at a major road junction within Epping Forest, and not therefore likely to generate noise complaints – was particularly puzzling. Clearly, there were many factors, social and economic, driving these changes. But even success could be problematic, as the case of The Tally Ho demonstrates. Run by Lilian Delaney from the late 50s, it was one of three venues she managed with her husband Jimmy, the others being The Kensington, West Kensington and the extremely louche Mandrake Club in Meard Street, Soho.(13) Jazz was performed at all of them, with The Tally Ho being particularly noted for its casual, freewheeling Sunday jam sessions. Crowds would spill out onto the street listening to the many musicians who dropped by to blow. The performances there spawned a couple of live albums: Jazz at The Tally Ho (1963) and Tally Ho Sunday (1966) featuring various sidemen whose collected credits would include playing alongside Don Rendell, Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated, Mick Mulligan, Graham Bond, Terry Lightfoot, Caravan and Soft Machine. Landlady Lilian Delaney sang with them too and was pretty decent as a vocalist. After US band Eggs Over Easy got a Monday night residency in 1971, crowds began flocking there to hear rock as well, encouraged by the free admission policy. Bands got a percentage of the bar takings, and so much beer was sold that the owners, Watneys, simply tripled the rent, resulting in Mrs Delaney quitting and the pub abruptly ceasing to feature live music. It was a thoughtless, self-defeating action by the brewery who really had no understanding of how to make the most of such a phenomenon.(14)

Leaving aside the likes of the Marquee, a small circuit of mainly inner-city venues were putting on live music at the beginning of the pub-rock period, and still doing so four years later as that scene shaded into punk and new wave. These were The Golden Lion, Fulham and The Greyhound, Fulham joined by The Kensington, West Kensington, the Hope & Anchor, Islington (both of which switched from jazz to rock in 1972), the Brecknock, Camden and The Half Moon, Putney. Moving a bit further afield there was the Winning Post, Twickenham, The Greyhound, Croydon and The Torrington Arms, Finchley. Added to this was a rare out-of-London gig: The Nags Head, High Wycombe. Here rock music had been a feature from 1968, promoted by Ron Watts, who also managed his own band, Brewers Droop, and acted as booking agent at Oxford Street’s 100 Club.(15)

These were the constants. Alongside them, but with a less continual (or reliable) schedule of bookings could be found The Windsor Castle, Harrow Road, The White Lion, Putney and the Telegraph, Brixton Hill.(16) To which one could add the Fishmongers Arms, Wood Green, where the music was staged in the Bourne Hall: a long wooden building at the rear. Originally a jazz venue (Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson recorded the Chris Barber band in action here in their 1956 documentary Momma Don’t Allow), by 1972 this was offering rock and roll revival acts as The Hound Dog Club. When not in use others used it as rehearsal rooms, with visiting journalist John Pidgeon considering that it was ‘one of those legendary London music pubs where countless bands had played the blues, before they became famous… draughty hall in need of refurbishment, its décor untouched for at least a decade, judging from the scraps of posters here and there advertising bands that once must have packed the place. Wall-to-wall bodies would be the only way to have warmed this tatty venue, I speculated, because the stingy radiators weren’t up to it’. He was right, and it never recovered its preeminence, though trying to establish when it last offered live music has proved difficult. There were many other, lesser-known, haunts.

Once rock bands began performing somewhat more frequently in pubs, additions included Dingwalls Dance Hall, Camden Lock, a long narrow warehouse with few windows, and, unusually for the time, eating facilities,(17) The Lord Nelson, Holloway, where live music was provided by Tom Healey 1973-75 and a trio of Fuller’s pubs, The Nashville, West Kensington, The Red Cow, Hammersmith and The Red Lion, Brentford all of which switched to rock circa 1974, after staging mainly country and western acts.(18) That year also brought in The Dublin Castle, Camden, run by the Conlon family from Mayo,(19) and Newlands Tavern, Peckham.

During 1975, with both Ace and Dr Feelgood enjoying commercial success, things expanded further with the reopening of The Bridge House, Canning Town. The landlord here was Terry Murphy, a former boxer, who had actually run music venues in the mid-60s, notably The Tarpot, Benfleet, which had staged acts like The Paramounts, the Southend band that would eventually evolve into Procol Harum.(20) No one would claim that Canning Town was in suburbia, but as a venue The Bridge House had similarities to places like Cooks Ferry Inn and The Village Roundhouse. A huge, mock-Tudor barn, its music and stage area had a capacity of a thousand, with often twice that many crammed in. Murphy was very precise about the economics: music was ok as long as the beer money covered the cost of the band. He was also clear that, by the 70s, large pubs needed live music to keep their takings at a level high enough to ensure their survival.(21)

By 1976, the impact of pub-rock, together with its London orientation, and the reconfiguring by various managers, booking agencies and record labels of how they launched a new act, led to the emergence of further venues. These included The Rock Garden, Covent Garden, The Pegasus and The Rochester Castle (both in Stoke Newington) and The Half Moon, Herne Hill which prior to then featured a mixture of folk and jazz. A couple of others reappeared too, such as The Moonlight Club(22) and The Castle, Tooting, shedding as it did so its Tooting Blues Club moniker. Finally, reflecting the politics of the era, a number of council-funded community centres appeared, some of which put on music regularly. These included The Albany Empire, Deptford(23) and Acklam Hall, Ladbroke Grove. Despite its name, the latter was a modern building, built on empty land underneath the Westway. Paid for by an Urban Aid grant sponsored by the GLC, it opened in 1975 with a benefit gig for North Kensington Law Centre, headlined by Joe Strummer’s 101ers.

London in the first half of the 70s had an abundance of live music venues, many of which were pubs. There were similar networks elsewhere, up and down the country, but with the music press and record labels solidly domiciled in the capital these were the ones that got reported and these were the places where emerging acts were studied.

Notes

1. Jimmy Power did play The Greyhound, but his contributions to this LP were recorded at The Little Favourite, off Holloway Road.

2. Interview with Michael Harty, 29 January 2022.

3. Interview with Frank McAweaney, 30 January 2022.

4. Several of the albums noted here were heavy sellers: Savoy Brown’s Looking In reached No 39 in the US and the Edgar Broughton Band’s eponymous release peaked at No 28 in the UK. The idea that one might see them in a local pub – and simultaneously on TV – without booking beforehand says a lot about how accessible live music was at that time.

5. One that did was Evans Supper Rooms, 43 King Street, Covent Garden. Dating back to 1856, the basement was used, 1967-68, by the Middle Earth Club.

6. Literally as well as figuratively: it was at the end of a narrow, ill-lit, cobbled street (Shepherd’s Lane). An ideal location for discreet and illicit encounters.

7. Side A was at the Deuragon. Side B was recorded at Peter Cook’s Establishment Club. Martine was considered ‘a forgotten original of British comedy’. See his obituary in The Guardian, 11 October 2002.

8. A compilation LP, Stars from Stars and Garters, reached No 17 in the UK charts in March 1964. Kirby’s own 16 Hits from Stars and Garters peaked at No 11 a month earlier. The TV show seems to have taken its name from The Star and Garter Hotel, Bermondsey, one of the great nineteenth-century entertainment saloons. For confirmation that bands played in such venues, note that The Searchers appear in a pub in Poplar in the 1964 film Saturday Night Out.

9. Also below the radar screen were an increasing number of reggae venues.

10. None of which should be taken as implying that landlords were hard up. In the mid-70s they might typically be earning, before overheads and deductions, between £800 and £2500 per week (£6000-£18000 per week today). Managers were paid a wage, about £80 a week (about £500-£550 a week now) but had various perks, such as keeping any profit from food sales. Many landlords and managers offered bands either a low all-in fee (£15-£40 for a gig) or an unpaid slot and after gauging the upturn in business came to a mutually beneficial financial agreement. Information provided by Alan Hooper, 8 January 2022.

11. Klooks Kleek occupied the first floor of the Railway Hotel. The premises here were brought back into use as The Starlight Club in the late 70s.

12. This was despite the Tithe Farm House putting on Bees Make Honey, Brewers Droop, Ducks Deluxe and Clancy up until 1974-75. Clearly, the owners did not appreciate the potential to maintain a high audience via live music shows.

13. All of which implies that the Delaneys were quite sophisticated people. Footage of The Mandrake Club is shown in Saturday Night Out. Known as ‘London’s only Bohemian rendezvous’ it was frequented by Daniel Farson and went through many incarnations, later being known as Gossips, Billy’s and Gaz’s Rockin’ Blues.

14. See Sarah Jane Delaney interview at: https://www.mixcloud.com/FrenchSpurs1/retropopic-491-lillian-delaney-the-tally-ho-of-kentish-town-the-birth-of-pub-rock/

15. The Nags Head clearly gives the lie to any notion that pub-rock began in London in 1972. Watts, who is not widely recognised as such, was clearly a major figure in the UK music scene in the 70s and 80s. See his obituary at: http://www.chairboys.co.uk/history/2016_07_ron_watts_obit.htm

16. The Telegraph was particularly opulent, having been designed by WM Brutton, an architect who did many immense nineteenth-century gin palaces, including The Fitzroy Tavern, Fitzrovia.

17. Dingwalls was initially managed by Howard Parker, formerly DJ at The Speakeasy and road manager for Jimi Hendrix. He vanished in the Mediterranean in the mid-70s, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QPKi7XntdMs He was succeeded by Dave ‘The Boss’ Goodman, former road manager for Pink Fairies, who also doubled as chef and DJ.

18. Hammersmith seems to have provided more music venues than any other London borough. There was also The Swan, Hammersmith Broadway, which had jazz up until 1977 and the Clarendon Ballroom, also Hammersmith Broadway, which did country and western until the late 70s and was the location for Dave Robinson’s wedding reception. (According to Michael Harty, ‘It had a bar next door that sold ‘Ullage’ to the ‘Winos’, which was basically the slops they collected, your feet would stick to the floor, as they never washed it!’) And, of course, there was Mecca’s Hammersmith Palais with its revolving stage and immense dance floor. The Palais staged many reggae acts from the mid-70s.

19. According to vocalist Suggs, Madness obtained their critical early gigs at The Dublin Castle after this exchange with Conlon, ‘He asked us what we played and we said country and western, and jazz – we thought that would be the thing to say when going in to ask for a gig at an Irish pub.’

20. The Bridge House had been a music venue in the late 60s. Bobby Harrison, ex-Procol Harum, obtained a residency there for his group The Freedom in 1969. Geographically, it was where the Essex gig circuit met the London gig circuit.

21. See Terry Murphy, The Bridge House, Canning Town: Memories of a Legendary Rock and Roll Hangout (2007) p109. Murphy was quite an operator, even running his own record label (the only pub landlord to do so) 1978-82. His book describes a world not dissimilar to that of Farson and Watts 10-15 years earlier, or even the recollections of John Osborne, whose grandparents had been publicans, recorded in A Better Class of Person (1981).

22. The Moonlight Club was slightly downstairs and to the rear within The Railway Hotel, West Hampstead, and therefore within the same building that had hosted Klooks Kleek.

23. The Albany was within The Albany Institute, a late nineteenth-century charitable endowment. Latterly owned by the GLC it was a community theatre project from 1972 and a music venue from about 1975 before being destroyed in an arson attack in 1978.

PETER BUCK

(PROMOTER: THE HARROW INN and THE SAXON TAVERN)

I promoted bands at the Harrow Inn, Abbey Wood from 1962 to 1974. After I’d done my National Service in the Army, I lived in Bermondsey and worked as a pipe-fitter and part-time musician, getting as far as being offered a slot in a TV orchestra. But my wife wasn’t keen on me working as a full-time musician, so I opened an R’n’B club instead. My partner, Tommy Brown, and I approached the landlord of the Harrow Inn and just asked if their hall was available. I think Tommy knew about it because he came from Dartford. The hall itself was a large building, immediately to the rear of the pub itself. The brewery wasn’t involved, and luckily for us we only dealt with two different landlords in the next twelve years. We paid them some money every time we used it – £5 or so – they ran the bar and kept the takings, and we kept the door money. We arranged a couple of bouncers, paying them about £2 each and rarely charged more than 4s (20p) to get in. The bands were paid about £15. It was licensed for 200 people by the London Fire Brigade, but we frequently went well above that, often as high as 700!

One of the first acts I had on there was Georgie Fame, with Ginger Baker on drums. Harry Starbuck, an 18-stone boxer, was one of my bouncers. He could knock someone out with one punch. There were fights, often when the band were playing, usually about something stupid, like someone knocking over a drink. But we never had to call an ambulance and the police were never involved. We did a couple of fundraisers for Oz magazine at the Harrow Inn. One with Pink Fairies and Skin Alley paying them £35 each. The Fairies drummer, Twink, did the entire set naked. There were 661 people there and after raising £132 for the cause, we still had £100 left to split with the promoter, John Carden. We did another with Hawkwind and they played so loud that the landlord was in a real state telling me to ask them to turn it down… I walked into the music room, and as I opened the door the soundwaves nearly knocked me over! We did well at the Harrow Inn but started to lose money towards the end, despite the building of the enormous Thamesmead Estate nearby. On 27 October 1972, for instance, we had 148 people to watch Supertramp, who got paid £60. After all the other deductions we ended up losing £23. Then, on 25 November, we got 594 people for the Edgar Broughton Band. We paid them £300, but still lost £100, of which £35 was down to the advertising costs.

So… I started promoting music at local colleges instead. I met the Student Union manager at Thames Polytechnic which had a fabulous hall, much bigger and better than the Harrow Inn, and we agreed I would book the bands there. Through him I also got involved with Bromley College. In 1976 I started doing bands at the Saxon Tavern in Catford but pulled out about eighteen months later as I was losing money. I started my own haulage business instead. I always wanted to be a musician, but failed, so putting on bands was my way of keeping in touch with the scene. There was no pressure on me to stop being a promoter, but I wasn’t earning regularly and things became difficult.

KEVIN BURKE

(GLENSIDE CEILI BAND and sessions for ARLO GUTHRIE, CHRISTY MOORE)

In London during the 70s I would typically watch bands at the Marquee or Dingwalls, mixing this with Irish sessions, often on a Sunday, at pubs like The Favourite, Benwell Road or The White Hart, Fulham. My favourite bands on the scene were Chilli Willi and the Red Hot Peppers, Brinsley Schwarz and the Kursaal Flyers. The best gig I saw was probably one of the last that Chilli Willi did. It was at the Roundhouse and lasted all day with several supporting acts. A great vibe. The Brinsleys played too: all wearing red tartan jackets and ties. They looked like The Shadows and did the same choreographed foot movements during their set! After I went to Ireland, in 1974, I started to lose touch, and by the end of the 70s I had no contact at all with the London scene. My recollection is that it was pretty fluid: places closed, but new places opened.

I was playing in Irish music venues from the 60s, as a teenager. My father was involved with the Glenside Ceili Band, occasionally helping them organise their gigs. They were the all-Ireland champions in 1966, and put out an album on Transatlantic a year later. He’d bring me along and I’d sit in with them. We did all the big venues on that circuit. The ballrooms: the Galtymore, Cricklewood; the Hibernian Club, Fulham; the Gresham, Archway; the Harp at New Cross; the Shamrock Club, Elephant and Castle and various church halls and so on. The audiences in the big ballrooms were immense, up to a thousand people in places like the Galtymore. At that point I wasn’t really playing for money. It was more like pocket money. Sometimes I got a few quid. Whatever the band was paid would be shared out amongst the men. Most of them had day jobs. In fact, not having a day job was frowned on, then. If you didn’t work, you weren’t respected. There was a real work ethic.

Later I did a lot of playing in pubs and folk clubs. In the pubs you might be watched by 70-100 people. The folk clubs were smaller, maybe 50-60 people, and more serious. I played at The Union Tavern, Clerkenwell when it was the Singer Club. This had been started by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger and had been held at various locations since the late 50s. There was another place, the Kings Stores, Widegate Street, near Liverpool Street, a room above a pub, where I sat in with The Peelers, Tom Madden’s band. They had a residency there. I was at school with Paddy Bush, brother of Kate. The Bush family lived in Welling, and their mother came, I think, from Waterford. Through Paddy I met Dave and Toni Arthur… I played on their 1971 LP Hearken to the Witches Rune.

I thought London had a really vibrant music scene back then. From the point of view of traditional music there were pub sessions all over the city. In fact, there was a bigger Irish music scene in London then than in Ireland, and as a young Londoner I had access to all these great players. There was music on seven nights a week, on top of which there were all the pubs with rock bands and all the bigger venues too up to and including places like the Lyceum and the Rainbow. I remember seeing BB King at the Hammersmith Palais!

Looking back, I would say that the Irish pub landlords were much more open to having live music in their bars. After all, it was a thing you got all the time in Ireland. You just didn’t have the same approach in English pubs. In Eltham, where I lived at that time, the atmosphere was very different when you went out for a drink, compared to say Islington or Camden. Live music, of any type, wouldn’t have worked so well in places like that.

THE MUSIC

Establishing that live music featured in pubs for a long time prior to 1972 is relatively easy. After all, we all remember the first time we drank in a pub – probably underage and buoyed by the thrill of the illicit – and likewise, we all remember the first band we saw. In many instances the two events may be related. A harder question to answer is if pub-rock really did exist as a discrete genre, when and how did it begin and what were its characteristics? To answer this, we need to answer another question: what was the UK music scene like circa 1971, between the disintegration of the Beatles and the emergence of David Bowie, Alice Cooper and Roxy Music?

The easy response to such a query is to reel off who was selling records then. The 60s behemoths – The Who, the Stones – strode on. There was the usual array of simple formulaic chart fodder, a huge amount of reggae, Tamla, soul and people like Tom Jones and Tony Christie who alternated between Saturday evening TV and cabaret. Then there were the album-selling acts. Singer-songwriters like Elton John and Cat Stevens and a whole slew of bands, from Atomic Rooster to Yes via Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd in the alphabetical compendium guides of the time.

What all these had in common was that, increasingly, they toured in large venues: the university and college circuit, town centre cinemas and ballrooms. The days of seeing any of them at your local pub were over. As for new acts, like Rod Stewart and The Faces and T. Rex, whilst their music was accessible with plenty of pop/rock and 3-minute songs, they too clearly aspired to all the trappings of fame: jets, limousines and overnight accommodation in immense hotel rooms. All of which came with a cost. Large PA systems, huge drum kits, massed ranks of amplifiers and speaker cabinets, possibly a light show as well, with a dozen or so roadies, drivers and general heavies needed to set it up, take it down and keep unwelcome interlopers at bay. Only good-sized venues could accommodate this, and touring, particularly if it included the US and Europe, with extended distances between gigs and multiple overnight stays, was expensive. By 1971, everything was much bigger in scale than had been the case only a few years earlier.

During the mid-70s, some bands began eschewing such trappings. A number of explanations were offered for this. Pete Frame, a shrewd observer, and editor of ZigZag magazine 1969-73, thought that the emergence of pub-rock was ‘a chance for bands to play low-key gigs and return to honesty and reality’. Specifically, he considered that Brinsley Schwarz were ‘certainly the popularisers of the pub scene and were responsible for the media focus’ after they took a residency at The Tally Ho, Kentish Town in the summer of 1972.(1) In 1976, The Encyclopaedia of Rock Volume 3: The Sounds of the Seventies acknowledged this but took a cautious view, stating that pub rock was ‘