Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

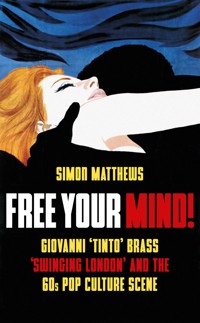

Between 1967 and 1970 Italian auteur Giovanni 'Tinto' Brass directed four feature films in London, each starring a woman as the main character. Exploring the political, cultural and sexual ideas of their time, often in a deliberate pop-art style, they contain much priceless footage of now forgotten neighbourhoods, galleries, clubs and events as well as an abundance of contemporary music. Free Your Mind! describes the films, their stars, how they were made, and their influence on the social history, pop culture, cinema, music and TV of the time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Simon Matthews

‘Psychedelic Celluloid covers the swinging sixties in minute detail, noting the influence of pop on hundreds of productions’– Independent

‘Addresses everything with a thoroughness and eye for detail that’s hugely impressive’ – Irish News

‘The ultimate catalogue of musical references in film and TV from the swinging sixties’ – Glass Magazine

‘Impressively comprehensive... positively jam-packed full of trivia and amusing anecdotes’ – We Are Cult

‘A must-purchase for fans of British films and pop music’ – Goldmine

‘For anyone with a love of the music, fashions, and the scene, or for anyone who simply adores movies, Psychedelic Celluloid is a handy book to own’ – Severed Cinema

FOREWORD

Tinto is one of the most clever and eclectic directors I have everworked with. He is like a dog which has broken loose of his chain (orisn’t too tied up) and runs free in the meadows of cinema – ‘his’ cinema unbound to the producer’s profit. Testament to this is his almost comic book-like delirious film Yankee, the most atypical Italian western of its time.

After all, Tinto comes from a lineage of artists. His grandfather was a painter who married a rich Russian woman and as a young man he frequented the Parisian Cinémathèque and the Nouvelle Vague circles. A truly free, eclectic,eccentric, and neatly untidy spirit.

A madman with a great sense of humour – a very important quality, as having a relaxed atmosphere on set is a necessity for me. I am not fond of directors who rant and shout, who go on set as if they are going to war. Tinto would step in with just the right amount of grit and verve, without ever falling into conflictual anxiety.

He was like a big kid who let his dreamlike fantasies take over. Thanks to his brilliance and technical abilities, he could translate the incredible things in his head onto the silver screen.

We shot Dropout and The Vacation togetherin 1970 and 1971 respectively. At the time we worked with my wife VanessaRedgrave because Tinto was dying to work with both of us. It was one of the most bohemian experiences I ever had in cinema. Something that could only happen in the 1970s, when youth counterculture and hippie principles were still echoing in the climate.

In Dropout I played a lunatic who escapes an asylum and kidnaps a woman. The two fall into a dangerous attraction and, in the end, I die at the frontier while she is murdered by her husband. Tinto played the dropout: an art dealer and pornographer. In THE VACATION, the roles were reversed where Vanessa played an allegedly insane woman and I played a poacher who falls for her.

They were regenerating and liberating filming experiences. Something outside the typical Hollywoodblockbuster box, where creativity is often trapped and hindered under enormous budgets.

Tinto’s approach was very much inspired by the New Wave and the English Free Cinema. We would often change location on the spot and improvise. We drove around like nomads, travelling with our skeleton crew in a cramped minivan alongside the equipment. We were able to seize opportunities according to circumstances without planning.

Additionally, as good Italians, even when we were travelling around England, if there were important football matches where Italy was playing, we would run around looking for a pub or any place thathad a TV to watch the game.

Many years later I asked him to appear in a film, Louis Nero’s La Rabbia. He accepted to do a cameo as long as he had a ‘beautiful lady with voluptuous breasts’ sitting on his lapwhile he delivered his lines.

The fact is that while the critics considered him a promising genius of anti-system cinema, his films didn’t initially gross much. After he threw himself into hardcore passionate romantic films with The Key, he found true commercial success and never looked back. Although indeed he was always intrigued byrelations with sex and the link between power and sex (as seen in Salon Kitty with Helmut Berger).

It wasn’t that he had become more serious than when we made films together. If anything, he was always serious but with that not-so-subtle hint of irony of someonewho plays with being a ‘master’ rather than really considering himself one (although he undoubtedly is in his own way).

Some critics theorised that he was obsessed with using a big cigar as a phallic metaphor, but this is far from the truth: he just enjoys smoking cigars, simple as that. When someone becomes important there are always scholars who try to identifycomplex meanings where there are none. Tinto mocked them without them realising, pretending to be the stereotype that film critics hadcreated about him.

In truth Brass is asly cat, with a flame of sharp, critical, ironic and self-ironic intelligence which burns behind his eyes. I am the first person to say he shouldn’t be taken too seriously - and he is the second. After all, as someone said, we don’t laugh about what we don’t love. Thank you, Tinto, thank you for letting me, part traveller on my mother’s side, breathe bohemian cinema. To me, you were and are a nomad of cinema.

Franco Nero

Preface

If you lived in London in the 1960s, you might have seen him. A small, portly man in his mid-thirties with his hair brushed back, hedgehog-style. Carrying a 16 mm Arriflex camera, he might have been searching for locations for one of his films, or just shooting whatever he happened to notice. It could have been early in the morning, filming the sunrise or recording dockers at work; possibly slightly later in the day, in amongst the commuters tramping across London Bridge or recording the soon-to-be-scrapped steam locomotives coasting noisily through Clapham Junction Station. Most of the time he might be on his own, but occasionally a small Italian-UK crew would be accompanying him. But never many people, enough to fit in a couple of cars at most.

His stars were often well-known, and easily identified by regular cinemagoers. But rather than deploy them inside a studio, and film them with stage-like conventionality, he would instead show them walking through unknowing crowds, the narrative constantly teetering on the point of breaking the fourth wall between the camera’s gaze and the audience’s eye. They would pass through shops, arcades, galleries and nightclubs; they would get on and off buses and tube trains; everything recorded quickly and spontaneously for posterity. What we see now is a city changing as he films it. Piecing together masses of footage at the editing machine, and deploying the skills he picked up from Roberto Rossellini, his dexterous fingers assemble a narrative that moves, like the shifting lens of a kaleidoscope, from the soot-blackened, ruined terraces and dowdy street corners of north Kensington to smart boutiques, noisy demonstrations and then out into the night. We see glimpses – and more – of the cultural revolution that rocked London and the world in the 1960s: Indica Gallery, the Roundhouse, Granny Takes a Trip and even a ‘happening’ at the Alexandra Palace amidst the peacocks and peahens of the day, before the dream faded.

I first became aware of Tinto Brass’s early films when researching my earlier book, Psychedelic Celluloid. Because it contains a score by The Freedom, a UK group that emerged out of Procol Harum in July 1967, this mentions Nerosubianco, a film considered by some to be his masterpiece. But trying to assess how much work Brass had done in London in the 1960s, or how much of the city he had caught on film at that time, took longer than expected, and became an ongoing project in its own right. As and when I could, I began piecing together an account of his endeavours. In February 2019, Shindig! magazine published a lengthy, and much more detailed, article on Nerosubianco and gradually a book began to take shape. With memories fading it seemed important to assess where Brass slotted into the hierarchy of directors and auteurs in the 1960s, and indeed how significant a figure in world cinema he might have become if the cards had fallen slightly differently for him.

None of this would have been possible without the cooperation and interest of Ranjit Sandhu, whose painstakingly assembled website on the career of Brass contains much information not accessible elsewhere. I am also grateful to the following for their time, responses and insights: Alan Sekers, Barry Miles, Mal Ryder, David Mairowitz, Bobby Harrison, Mike Lease, Anthony Cobbold, the late Carla Cassola, Pete Brown, Stephen Frears, Ken Andrew, Don Fraser, Franco Nero and Alexander Tuschinski.

This is the story of the only European director who made four feature films in London in the 1960s.

1

VENICE

Before considering the career of Tinto Brass, we should remember that he is Venetian: from a city with its own cultural traditions that, in historical terms, only recently became part of Italy. His family trace their ancestry back to the lands on the eastern side of the Adriatic, which, for centuries, were part of the Hapsburg domains. It is uncertain whether they were ethnically Slav or German. They may even have originally been Italian, only to be subsequently ‘Slavicised’ or ‘Germanised’ during the numerous shifts of political control in that area. What is clear is that by the mid-nineteenth century his great-grandfather, Michele Brass, was resident in Gorizia (in German, Görz) where he was active in dissident political circles. He identified as Italian and was an ‘irredentist’, one of the many Italian-speaking citizens of Austria-Hungary who wanted the area they lived in to secede and become part of Italy.

Considering oneself Italian then, as now, did not imply being part of a homogenous culture that radiated outwards from Rome. In fact, identifying specifically with Venice was perfectly compatible with having roots in the north and east of the Adriatic, as these were areas that had once been part of the aristocratic city republic. Being Venetian, for instance, meant having a different, and in some ways more cosmopolitan, history compared to those who considered themselves Neapolitan, Sardinian or Sicilian. The prominence of the city dated back to 1082 when it was granted tax-free trading privileges throughout the Byzantine Empire. With the benefit of this concession, a string of Venetian settlements, ports and fortresses were established through Slovenia, Croatia, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey and Cyprus which combined with the city’s easy access to the Alpine passes into northern Europe gave it a significant share, for centuries, of trade with China, India and Japan. Because of this network of territories, trading bases and trading arrangements, Venice enjoyed world power status for approximately four hundred years. It accrued much wealth and contained a diverse population, including a significant Jewish community, famed for their residence in ‘the ghetto’. After 1453, the advance of Islam through Europe gradually eroded this position, and with the fall of Rhodes in 1522, Venice ceased to control trade with the east. But even after this the city remained a useful mid-range power, and an important player in coalitions against the Ottoman Empire. The Venetian navy took part in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and it fought alongside Austria and Poland in 1684.

Venice’s existence as a separate state ended in 1797 when the city and its surviving possessions were traded by Napoleon with Austria, in an arrangement that saw Austrian Flanders (Belgium) become part of France. Confirmed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austrian control of Venice was noted for its suppression of Italian political aspirations, a policy that united a great many of those of Italian descent in a hatred of the Hapsburg regime. Risings that attempted to restore Venetian rule, either locally, or across its former Adriatic territories, or that even aimed at a broader ‘Italian’ unity, were suppressed in 1821, 1830 and 1848. The city failed too to profit from the 1859 conflict between France, Sardinia and Austria and, with its immediate surroundings, only became part of Italy (created as a state in 1861) after 1866 when, despite experiencing defeats on land and sea, Italy successfully allied itself with Prussia against Austria. Under the terms of the Treaty of Vienna, which confirmed Venice would henceforth be part of Italy, Italy was obliged to abandon any future claims to parts of Istria and Dalmatia that contained a large Italian population. These remained within Austria, and because of this, ‘irredentism’ there was strengthened. Most Italian citizens of what was now called Austria-Hungary identified strongly with Venetian culture: its distinct dialect, much used in Italian theatre comedies as the coarse language of common people, its annual carnival with elaborate disguises, costumes and masks (an event banned in Venice under Austrian rule) and its immense artistic tradition, personified by Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Canaletto and many lesser-known figures.

This was the world that Michele Brass lived in, shaping both his political views, and those of his son, Italico.(1) Born in 1870, Italico proved to be very talented at painting. He trained as an artist in Munich under Karl Raupp from 1887 and then in Paris under Jean-Paul Laurens from 1891, where he won bronze medals at the Exposition Universelle and at the Salon. Shortly after this he married Lina Vigdoff, a Russian medical student from Odessa, and settled with her in Venice. It was propitious timing. The first Biennale was staged that year, and quickly became a national and international event, superseding the gatherings of artists, architects and writers that had previously taken place at the Caffè Florian. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Venetian art was undergoing a revival. This was led by Ippolito Caffi (who died at the Battle of Lissa in 1866 whilst serving as a war artist) and galleries across Europe began exhibiting the work of painters like Eugene de Blaas (like Brass, an Austrian) and Guglielmo Ciardi. Like Ciardi, Italico Brass painted in a post-impressionist style and, once he had the funds to do so, assembled his own art collection.

His reputation spread and in 1899 one of his works was purchased by King Umberto I of Italy. In 1907 another, The Procession Returning from the Island of San Michele, inspired the Ezra Pound poem ‘Per Italico Brass’. Resident, like Italico Brass, in the Dorsoduro area of Venice, Pound spent 4 months in the city in 1908, during which he self-published A Lume Spento, his first collection of verse. What appears to have attracted him to Brass’s picture was the way it fell stylistically between different schools, representative neither of impressionism nor of photographic realism. To be noticed by Pound, who was only 23 then, may not have seemed of much significance at the time, but in the years that followed, with Pound championing a revolution in literature via his enthusiasm and support for TS Eliot and James Joyce this would have been no bad thing. Nor, after 1924 when he returned to Italy from Paris, would Pound’s later gravitation to support for Mussolini.(2)

Granted a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1910, Italico Brass’s reputation continued to grow. Supported by the journalist and critic Ugo Ojetti (another irredentist, and subsequently a signatory of the 1925 Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals) his work was exhibited at the 1911 International Art Exhibition in Rome and later toured as part of a travelling show that visited Budapest, Berlin and Paris. In 1914, a solo exhibition in Paris followed, organised by the legendary art dealer and gallery owner Georges Petit, who some years earlier had been one of the first promoters of the Impressionists. After this his work was shown in Buenos Aires and San Francisco, where both he and Ciardi won gold medals, Brass for the picture Il Ponte Sulla Laguna.

His ascent into the orbit of Georges Petit took place against a background of monumental international events. War broke out between Russia, France, Britain, Belgium and Serbia on one side, and Germany and Austria-Hungary on the other in August 1914, with the Ottoman Empire added to the conflict later that year. As an Austro-Hungarian citizen, Italico Brass now found himself, theoretically, an enemy of Petit. Fortunately, Italy, his adopted country, although it was part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, declared itself neutral. By March 1915 it had cancelled its treaty obligations, switched sides, and sensing the opportunity to make territorial gains, had declared war on Austria-Hungary (May 1915) and the Ottoman Empire (August 1915). It refrained from tangling with Germany until August 1916. Willingly granted Italian citizenship, Brass followed the footsteps of Ippolito Caffi half a century earlier, and was appointed an official war artist by the Italian high command. Posted to the Duke of Aosta’s Third Army he was given the task of documenting military events on the Isonzo front. For the next three years he took part in the various advances and retreats in that area, keeping a diario pittorico, and emerged unscathed to be awarded an exhibition of his works, dedicated to Venice, in the Galleria Pesaro in Milan in 1918.(3)

With peace, and a considerable income from the sales of his work, Italico Brass bought the Scuola Vecchia dell ‘Abbazia di Santa Maria della Misericordia (the Old School of the Convent of Saint Mary of Grace) in the Cannaregio district of Venice. More than six hundred years old, by the early twentieth century it was in an advanced state of disrepair. He began an extensive restoration, using it to store and display his large art collection, whilst commissioning additions, such as a round tower, an oriental-style balcony and some galleries inside the main hall as well as a complete redesign of the walled garden and its Gothic colonnade. For the remainder of his life, Italico Brass divided his time between painting, and being a connoisseur of sixteenth-, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Italian and Venetian art. He also participated fully in the municipal affairs of Venice as a member of the Commission on Public Buildings, the Board of Directors for Venice’s Municipal Museums and the Scientific Committee that prepared the exhibitions for Titian (1935), Tintoretto (1937) and Veronese (1939). He would be joined in much of this activity by his son, Alessandro Brass.

Born in 1898, and Italian by birth, Alessandro had volunteered for war service in 1916. He was wounded, and after the war became a lawyer in the office of Francesco Carnelutti, a significant figure in Italian commercial law. Thereafter, he pursued a legal career, leavened with politics. Like many Italian ex-servicemen, Alessandro Brass regarded the gains made by Italy at the Treaty of Versailles (Trieste, and a few enclaves in the Adriatic and Aegean) as inadequate. His irredentism translated smoothly into fascism and he participated in the October 1922 ‘March on Rome’, an event which led to the appointment of Mussoloni as Prime Minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. In the years that followed, Alessandro, like his father, became a noted art collector whilst rising to prominence in fascist circles in Venice. By March 1939 he was considered sufficiently reliable to be appointed a delegate to the fascist ‘corporate’ parliament, which sat until August 1943, though it had very little actual power. He married in 1929 and had 4 sons, the second of whom, Giovanni Brass, born in 1933, would spend much of his childhood being brought up by his grandparents. Noting his prodigious appetite for drawing, they nicknamed him ‘Tinto’ after Tintoretto, the great Venetian artist of the 1550s.

Whatever his preferences in domestic politics, Alessandro seems to have had a reasonable grasp of the reality of Italy’s position. In 1940, with the country at war with France, Poland, the Netherlands, Norway and the British Empire, he moved his family out of Venice to Asolo. Here, 32 miles north-west of the city, he had access to a property formerly owned by the Earl of Iveagh, and, prior to that, by Eleanora Duse. Regarded in the 1890s as the greatest actress of her time, Duse was noted for her relationship with Gabriele D’Annunzio, poet, playwright, novelist and leading Italian irredentist. A controversial figure, D’Annunzio was regarded by many on the Italian political right as having played John the Baptist to Mussolini’s Jesus.(4) In Asolo, securely out of harm’s way with his grandparents, mother and siblings, Tinto grew up in relative peace and had his first exposure to film in the local cinema, watching Charlie Chaplin silents and Walt Disney cartoons. He may have been aware too, though only a child at the time, that his grandfather, in a late creative flowering, designed the sets for the Andrea di Robilant film Canal Grande.(5)

Not that Italico Brass lived to see it. He passed away two months before it was released during a hectic period that saw Mussolini deposed, much of Italy become a battlefield, the government surrender to the Allies, Germany invade and occupy most of northern and central Italy, and the King and his government flee, switching sides and joining the Allies. Alessandro Brass, no longer required in a parliament that had ceased to function, seems to have been politically wise enough to see how matters would end and, although resident in a part of the country that remained under fascist rule, rejected an offer of a position in Mussolini’s pro-German Salò Republic.

The Brass family survived the final stages of the war, which concluded for them when Venice was liberated by the UK 8th Army on 30 April 1945. With Alessandro’s prior commitment to the Mussolini regime well-known, and employment initially denied to him, they seem to have survived for a while by distributing some of Italico Brass’s art collection to various museums and even auctioning off a few pieces. (References can be found to works obtained from them by the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art prior to 1940. They seem to have continued this in the immediate post-war period, at a time when acquisitions from Italy were classed, in the absence of a peace treaty, as trading with the enemy, and subject to stringent taxes.)(6) With fascism vanquished, the Christian Democrats began their long period of political control, a referendum abolished the Italian monarchy and the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty stripped Italy of its Venetian outposts along the Adriatic, abruptly extinguishing the raison d’être of the irredentists.

By this point Giovanni ‘Tinto’ Brass was 13 years old, a keen amateur photographer and also a nascent film director, shooting his own amateur productions on an 8mm cine-camera he had been given as a present. In addition to this, not untypically for any boy of that age, with the onset of puberty and adolescence he had begun rebelling against his father’s wielding of ‘absolute authority’, and a family he regarded as ‘bourgeois, rich, fascist’. He also seems to have been sexually precocious, taking himself off to brothels, then state-regulated in Italy. Modelled on the French system, and introduced in Italy after the 1861 unification of the country, in Brass’s account these were not significantly different from, and certainly no worse than, extremely louche nightclubs. The sense of transgression that he obtained from such adventures also transferred to his rising political consciousness, living as he was at a time when many Italians supported Palmiro Togliatti and the Communist Party of Italy (PCI). Polling 14% and winning 6 seats in the June 1946 elections, the PCI were one of the larger parties, and opposed to both the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats. In Brass’s eye, they were, therefore, politically transgressive, at a time when he was exploring sexual transgression. They were also markedly more popular in Venice (where they polled 21%) than in many other parts of the country. Their support grew subsequently, and they might have entered government later in the decade had the US not issued instructions – in May 1947, as part of the terms set for Italy receiving Marshall Aid – that Togliatti and his supporters were to be excluded from any access to control of the state, an arrangement that remained in force for many years, even when the PCI polled as high as 34% in 1976. Keeping this exclusion in place over such a lengthy period required constant political adjustments, and the result was that Italy had 47 different cabinets down to 1991, at which point, with the disintegration of the threat from the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc, matters eased off a bit.

Tinto’s wayward behaviour outraged his father, who went so far as to commit his son to the San Clemente lunatic asylum in the Venetian lagoon. Built in 1844, this was a mental hospital on a tiny island that treated people suffering from various types of madness, including sexual hysteria. It also had a darker side, from what was then the immediate past: Mussolini had imprisoned his first wife Ida Dalser there until her death in 1937. Chastened by this experience, Tinto returned home and continued his studies. By 1950 he had started a law degree at the University of Padua, where he did well at his exams and, as a reward, was given a 16mm cine-camera. Around 1951 he met, through her brother Arrigo, Carla Cipriani, with whom he formed a relationship based on a mutual love of cinema. She was part of the Cipriani family who were celebrated for owning Harry’s Bar, one of the most fashionable attractions in Venice, and a venue noted for its stellar customers: Ernest Hemingway drank there in 1948 and it was frequented by many of the stars, directors, producers and writers during the annual Venice Film Festival.

Brass’s military service took him away for much of the time between 1951 and 1953, after which he returned to continue his studies at Padua. When not working at his law degree he continued to see Carla and expanded his social circle further by mixing with many local artists, including Albino Lucatello. A communist and Marxist, Lucatello was inspired by the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, several of whom had fought as partisans in the armed struggle against fascism. Their manifesto was published in Venice in 1946, and they exhibited as a movement at the Venice Biennale two years later. It was a sensational show. As well as their work an opportunity arose when, due to complications caused by the Greek Civil War, the official Greek entry failed to arrive. This resulted in a vacant pavilion, which was taken by Peggy Guggenheim who filled it with modern avant-garde work from her own collection. It was the first time most people in Europe had seen Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko outside of niche New York galleries, and proved to be something of a turning point in public awareness of modern art. The fiercely political neo-realism that had prevailed during the immediate post-1945 period now gave way to modernism and experimentalism based on abstraction, use of materials associated with modern life and mass production. Art was becoming less involved in day-to-day politics, and more observational, detached. The era of abstract expressionism had begun. Tinto Brass’s politics changed around this time too, settling into a kind of anarchic non-conformism. At some point between his brief sojourn on San Clemente and his ongoing legal studies he became familiar with the work of Wilhelm Reich, a prominent Austrian psychoanalyst in the 1930s who proposed that neurosis was rooted in sexual and socio-economic repression. Reich believed, for instance, that sexual freedom could trigger political change leading to lasting happiness through society. His books Die Massenpsychologie des Faschismus/The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933) and Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf/The Sexual Revolution (1936) were widely read studies on the nature of authoritarianism and how it oppressed the natural urges of the people.(7)

No longer the avant-garde they had seemed only a few years earlier, the members of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti dispersed, and the movement lost momentum, though Lucatello, who was from Venice, remained active in the city’s cultural life, and eventually won the Tursi Prize at the 1956 Biennale. In 1953, he married Giselda Paulon, the daughter of Flavia Paulon. A hugely influential figure at the Venice Biennale, Venice Film Festival and Trieste Science Fiction Festival, Flavia Paulon helped Peggy Guggenheim set up her gallery in Venice in 1949 and also owned the very highbrow film magazine Sequenze.(8) Through his friendship with Lucatello and Giselda Paulon, Brass got work from Flavia as a photographer at Cameraphoto, the Venetian news agency, and was engaged, during the summer of 1954, to cover the Venice Film Festival. (As it happens, this was a year with a terrific set of entries including The Caine Mutiny, La Strada, On the Waterfront, Rear Window, Senso and Seven Samurai.) He repeated this work in 1955 and 1956, and it was whilst working in this capacity that he met Lotte Eisner, the co-founder of the Cinémathèque Française. He was able to obtain Lotte Eisner invitations for prestige events – premieres, launches, press conferences and so on – and in return she suggested that if he should visit Paris, he might want to drop in and visit her at the Cinémathèque Française, where the prospect of a position was not out of the question.

Through 1956 and into 1957 Brass completed (and obtained) his law degree at Ferrara, where he was taught by Giuseppe Bettiol, a significant figure in the Christian Democrats and a leading Italian jurist in the post-war period. He made it clear to his family that he did not wish to practise law, or work in the legal profession: he wanted instead to work in film, or at the very least photography. His Plan A was to try and obtain work in Rome, where most of the producers and studios were based. He spent a couple of weeks there in July 1957 but he was rebuffed and failed to gain even the most modest employment in the industry. That done, his Plan B was to visit Paris. He did so, met Lotte Eisner and was offered an unpaid position (today we would say internship) at the Cinémathèque Française with accommodation included in a tiny, nearby flat. His job was to act as projectionist at their regular screenings and manage the screenplay library and still photograph library. He accepted. In October 1957 Carla Cipriani joined him from Venice and they married. He was 24 years old, and had worked as a news agency photographer at 3 successive Venice Film Festivals. He came from an artistic family with abundant artistic, cultural and literary connections and was now working in one of the most important creative centres of the French film industry.

Notes

1. For a summary of Italico Brass’s career in English, and examples of his works see: https://rjbuffalo.com/italico.html

2. On Pound and Italico Brass see: https://www.nonsolocinema.com/venezia-1908-ezra-pound-e-italico.html

3. A collection of Italico Brass’s war paintings, La Grande Guerra. I racconti pittorici di Italico Brass by Enzo Savoia and Francesco Luigi Maspes appeared in Italy in 2018.

4. On Duse and Asolo see: http://www.asolo.it/en/cosa-vedere-asolo/casa-duse-asolo/ The Earl of Iveagh, formerly Rupert Guinness MP, acquired a shoe making factory in Asolo in 1938. See: https://www.scarpa.co.uk/history/ Italian Wikipedia records that he ‘also owned land in Italy, in the Veneto region of Asolo . Here he stayed in the house that once belonged to Eleonora Duse . During his stay in Italy in 1938, he decided to bring together the best craftsmen in working leather and hide, founding the Società Calzaturieri Asolani Riuniti Pedemontana Anonima: SCARPA.’ This is missing from his UK/US entry. Investing in manufacturing in Mussolini’s Italy would have required a close and friendly relationship with local, and government level, officials.

5. Throughout the war Italico and Alessandro Brass loaned pictures from their collection to the Italian state for selected exhibitions and private viewings, the latter attended by leading figures across fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Mention of this, and the appropriation of Jewish-owned items (in which there is no suggestion of any involvement by the Brass family), can be found at: https://www.lootedart.com/web_images/pdf2019/XXII_2019_BARTOLI.pdf The trailer for Canal Grande can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L3kAqmqFIBw

6. For examples of post-war sales see: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1947.210 and https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437242

7. On Reich see Adventures in the Orgasmatron: Wilhem Reich and the Invention of Sex by Christopher Turner, Fourth Estate 2011.

8. Guggenheim’s contribution to Venice, culture and art is outlined at https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/en/art/in-depth/peggy-guggenheim/memories/ which contains comments and recollections by Arrigo Cipriani (brother of Carla) and Giancarlo Paulon (brother of Giselda).

2

FROM THE CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE TO YANKEE

The Cinémathèque Française was, and still is, an immensely prestigious organisation. It was founded, with an initial collection of 10 feature films, in 1936 by Henri Langlois (then only 22 years old), Georges Franju and Jean Mitry. Initially it concentrated on acquiring silent films, which, following the appearance of sound cinema earlier in that decade, were often being unceremoniously thrown away. Deemed to have no further commercial use, reels of silent film were usually melted down to extract the valuable nitrate from the stock on which they were printed. Langlois’s very first acquisition was the German silent horror The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, and his privately run and funded organisation acted as part-cinema and part-museum, saving many films which were at risk of vanishing and preserving other related items such as cameras, projection machines, costumes, and vintage theatre programmes. Much of this was less-than-glamorous work, and involved rescuing reels of film from recycling facilities, financially strapped distribution houses, and even flea markets. It was also an entirely private undertaking. Its nearest equivalent, the British Film Institute, had been established by Royal Charter in 1933 and received a small amount of funding. By comparison Langlois and his colleagues worked with whatever resources they could conjure up themselves.(1)

During the occupation, the Vichy regime allocated them office space in the same building that accommodated the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs. For a period, Langlois organised secret showings, in a hall named the Musée de l’Homme, of Soviet and American films the Germans had outlawed. Jean Rouch, at that point an engineering student, and later a prominent post-war documentary maker and anthropologist, wrote ‘…In this empty Paris of the German occupation, in 1940-41, the Musée de l’Homme was the only open door to the rest of the world…’ (2)By 1942, the Germans had an outright ban on British and American films, as well as a list of French films they considered subversive. Langlois and his colleagues came up with various methods to conceal films the Germans wanted destroyed. Some hid film canisters in their homes and gardens, others, like his Jewish-German emigré and film historian colleague Lotte Eisner, secreted a cache of films in the dungeons of a chateau in the Unoccupied Zone of southern France. (From the late 1950s Eisner would mentor a new generation of German filmmakers, including Herzog, Schlöndorff and Wenders.)(3) In a country that prided itself on its cultural integrity, all of these activities contributed to the mythological status of the Cinémathèque.

After the war, the French government provided a small screening room, staff and subsidy for the collection, which initially was based in the Avenue de Messine. Here, Langlois held marathon film screenings, many of which were attended week after week, and film after film, by the cinéastes and students who would go on to create French New Wave cinema: Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, Pierre Kast, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Roger Vadim, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol. Often seated in the front row of Langlois’s viewing theatre, they became known collectively as ‘les enfants de la cinémathèque’.

By the time Brass arrived in 1957, Langlois was responsible for an archive of over 40,000 films, an enormous, personally assembled collection of features, shorts, cartoons, travelogues, newsreels, documentaries, experimental works and even ‘home movies’. It was regularly added to as well, with production companies voluntarily depositing copies of their latest works and Langlois constantly sourcing unwanted or redundant material from distribution libraries. It was a fascinating place to work… with, importantly for Brass, unprecedented opportunities to view material rarely if ever seen in public. There was also the chance to work alongside Langlois on various projects, and by so doing, learn the art of editing and directing from scratch. One such project, and Brass’s first ‘credit’, was a possible documentary on Marc Chagall, the legendary Russian-Jewish modernist artist, who had come up with the idea that his life might best be portrayed by making a film about his paintings. With Frédéric Rossif (with whom Langlois had made an acclaimed documentary study of Henri Matisse a few years earlier) filming began – expensively, on 35 mm and in colour – in 1952. Langlois eventually asked Joris Ivens to supervise and edit the material. Ivens was an internationally renowned Dutch documentary maker and David Perlov, a Brazilian-Jewish student at the École des Beaux Arts (and via that a regular attendee at the Cinémathèque Française) was brought in to assist him, with Brass working alongside. At some point in the late 1950s/early 1960s the footage vanished before a final cut had been agreed and the full work is now presumed lost. Whether this was accidental or not is a moot point, as a rival effort, Chagall (1963), narrated by Vincent Price and directed by Lauro Venturi appeared shortly afterwards and went on to win an Oscar as Best Documentary Short at the 1964 Academy Awards.(4)

Brass also had the time and opportunity to shoot and edit his own material. An early effort from him was Spatiodynamisme (1958) a short colour documentary that he edited and co-directed with Nicolas Schöffer, about one of Schöffer’s interactive robotic sculptures.(5) A Hungarian-French artist, Schöffer had become known after presenting the Spectacle Spatiodynamique Expérimental, which was exhibited at both the Théâtre d’Évreux in Évreux, Normandy and Grand Central Station in New York. Part light-show and part kinetic art, the short film featured very rapid editing by Brass. Schöffer remained fashionable for many years, and one of his self-propelled artworks is used in the promotional film for the February 1968 Brigitte Bardot song Contact (the B-side of Harley Davidson and, like that, a Serge Gainsbourg song) where she wears a Rabanne dress of the same kind featured in the films Casino Royale and Barbarella, and chants out her lyrics in the style of a robot in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.(6) For Brass to be involved with this type of work in 1958 was very cutting edge, and it is intriguing that his entrée into editing and directing came via documentaries about noted artists (Chagall and Schöffer) rather than any conventional dramatic themes.

Through Ivens Brass came into contact with Alberto Cavalcanti.(7) Cavalcanti hired Brass as assistant director on La Prima Notte/Venetian Honeymoon, a big budget Italian/French production shot in August-September 1958 in Venice with Martine Carol, Vittorio De Sica and Claudia Cardinale. After this commercial concoction he went, again as assistant director, to India: Matri Bhumi, screened as India 58 in France. This was an extremely prestigious, feature-length documentary directed by Roberto Rossellini and made by him, at the invitation of Jawaharlal Nehru, in India between 1956 and 1958. Famous for Rome: Open City (1945), Germany, Year Zero (1949) and Europa ’51 (1953), Rossellini was a renowned figure in world cinema and his films did well up until his scandalous affair with Ingrid Bergman on the set of his 1951 film Stromboli. In 1957, whilst filming in India, Rossellini had another affair, this time with Bengali screenwriter Sonali Das Gupta, and soon after, Bergman and Rossellini separated. Rossellini returned with Gupta to Paris, where, in somewhat fraught circumstances, and once more attended by scandal, he and Brass edited the footage.(8) It premiered at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival and featured at the Moscow Film Festival that same year. Commercially it did little, but critics liked it, notably Jean-Luc Godard who proclaimed ‘…Today, Roberto Rossellini has re-emerged with India 58, a film as great as Que Viva Mexico! or Birth of a Nation and which shows that this season in hell led to paradise, for India 58 is as beautiful as the creation of the world…’ (9) Rossellini kept Brass on for what was hailed in some quarters as his comeback film: Il Generale Della Rovere, a hard-hitting war drama set in Genoa, during the German occupation of northern Italy. Starring Vittorio De Sica, Hannes Messemer and Giovanna Ralli it was much admired and won the Golden Lion at the 1959 Venice Film Festival, subsequently getting a US and UK release in 1960-1961.

From this Brass moved on to L’Italia Non è un Paese Povero (1960), a government-funded, feature-length documentary about mining and mineral wealth, and the initiatives being taken to extract and distribute recently discovered oil and gas deposits. This reunited him with Joris Ivens, who directed from a commentary written by Alberto Moravia. Much liked by filmmakers, Moravia’s books included La Romana (1947), filmed in 1954 with Gina Lollobrigida, and La Ciociara (1957). The latter was made into a film, Two Women, in 1960, directed by Vittorio De Sica and starring Sophia Loren who won an Academy Award for her performance. Later adaptations of Moravia’s work would include Le Mépris/Contempt, directed by Jean-Luc Godard in 1963 with Brigitte Bardot, and Il Conformista/The Conformist, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci in 1970, with Jean-Louis Trintignant. In L’Italia Non è un Paese Povero, however, Ivens chose to concentrate on the poverty of the traditional Italian peasantry, and how little they received from the profits produced by the energy companies after they had vacated their land, rather than the ‘progressive’ message about a country being modernised. Inevitably, a clash occurred between the director and RAI TV (the production company) and the film was blocked for political reasons. Ivens took the only full-length, uncut print and gave it to Brass who took it to France for safekeeping.(10) A much shorter version eventually emerged; later accounts credit Vittorio and Paolo Taviani as co-directors with Ivens, though both brothers, then working as journalists, were originally hired, like Brass, as assistant directors.

Brass’s time at the Cinémathèque Française came to end in 1960, with the organisation itself in some disarray. It lost a portion of its collection, thought to include over a hundred features, to a nitrate fire on 10July 1959, including the only copy of the 1931 Erich von Stroheim film The Honeymoon. Langlois had been loaned this by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and his less than rigorous attitude to acquisition and collection and his generally unconventional methods came in for considerable criticism following this debacle. The International Federation of Film Archives (of which Langlois had been a founding member in 1938) were particularly strident in voicing their concerns, and eventually the French government stepped in. André Malraux – de Gaulle’s Minister of Culture –was appointed to the Cinémathèque board and funding was provided to put the body on a more stable footing. One consequence of this was an improvement of the conditions and pay for the staff. Brass does not seem to have been under any requirement to leave but took the opportunity to do so anyway.

Having worked with Joris Ivens, Alberto Cavalcanti and Roberto Rossellini, Brass now felt ready to make his own, full-length films for cinematic release. Working at the Cinémathèque Française he had enjoyed access to the vast amount of documentary footage in their collection, much of which had never been publicly screened. With Langlois’s permission, from 1959 he began editing together previously unseen newsreel material of political events and wars in the twentieth century and using it to illustrate a commentary written by himself and Gian Carlo Fusco. The end result was Ça Ira, Il Fiume Della Rivolta. A statement against state repression, and in favour of personal freedom, the film took its name from the song Ça Ira (It’ll be fine), one of many sung during the French Revolution. Zebra Films, the same company that had done Rossellini’s Il Generale Della Rovere, agreed to produce. Run by Moris Ergas, their other productions around this time included Adua e Le Compagne/Hungry for Love (1960, with Marcello Mastroianni and Simone Signoret), Kapo (1960, with Susan Strasberg and directed by Gillo Pontecorvo), Senilita/Careless (1962, from an Italo Svevo novel with Claudia Cardinale and Anthony Franciosa) and La Steppa/The Steppe