Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Inklings

- Sprache: Englisch

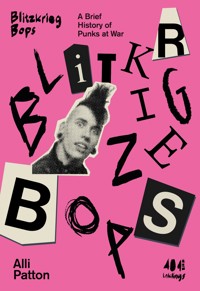

What happens when aggressive, riotous punk music becomes the peacemaker? Chronicling a history of punks at war, Blitzkrieg Bops studies bands who have soundtracked a movement —including Pussy Riot, Stiff Little Fingers, National Wake, Wutanfall, Los Pinochet Boys, Rimtutitkui, The Kominas & more — creating music to overthrow corrupt governments, stomp out oppressive regimes, fight the establishment and, in turn, fight for their lives.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Blitzkrieg Bops

Published by 404 Ink Limited

www.404Ink.com

@404Ink

All rights reserved © Alli Patton, 2024.

The right of Alli Patton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining the written permission of the rights owner, except for the use of brief quotations in reviews.

Please note: Some references include URLs which may change or be unavailable after publication of this book. All references within endnotes were accessible and accurate as of June 2024 but may experience link rot from there on in.

Editing & proofreading: Heather McDaid

Typesetting: Laura Jones-Rivera

Cover design: Luke Bird

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones-Rivera

Print ISBN: 978-1-912489-90-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-912489-91-6

404 Ink acknowledges and is thankful for support from

Creative Scotland in the publication of this title.

Blitzkrieg Bops

A Brief History of Punks at War

Alli Patton

Contents

Playlist

Introduction

Chapter 1: 1970s: Dancing on the Corpse of Apartheid

Chapter 2: 1980s: Eager to Live at Any Cost

Chapter 3: 1990s: Not Alone in the Darkness

Chapter 4: 2000s and 2010s: Keeping the Flame Alive

Conclusion

References

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Inklings series

Playlist

If you’re looking for the perfect soundtrack to the book, you can listen to Alli’s ‘Blitzkrieg Bops’ playlist on YouTube: rb.gy/b2t4d6.

Enjoy.

Introduction

Frenzied and furious, strings thrash like bullets ripping through the air. A barrage of drumbeats hit like heavy boots to soil. Through the roar of sound and fury, a distant voice cries out like orders in battle. With each blistering note, the bullets fly, the tanks roll out, the feet march on, and the blitzkrieg bops.

Since its inception, punk music and its subculture have defied convention, first emerging from a profound aversion to all things mainstream. Angry, unruly, and equipped with an “anti” ethos – aggressively anti-establishment, anti-authoritarian, anti-corporation, and anti-conformity – punk became a rebellion bound in leather, secured by safety pins, and informed by an innately anarchic resolve.

Exploding almost simultaneously in New York and London in the mid-1970s, early punk musicians traded in the polished, often excessive stylings of popular rock for a rougher, more stripped-down approach, resulting in the genre’s quintessential sound: a cacophony of shouted vocals, snarled chords, and distorted notes soundtracked this youth crusade, a cause among the alienated and enraged.

Punk predecessors examined society and culture through fuck-you-tinted glasses, crafting songs meant to ignite collective rage using blunt, socially charged lyrics. Many of the genre’s English forebears deployed their combative rock to critique the monarchy, aristocracy, and working-class life. Their U.S. counterparts were more fueled by angst, liberating listeners from American ideals by bashing their parents’ middle-class values and prophesying the evils of suburban conformity.

In the United Kingdom, nihilistic tyrants the Sex Pistols may have initially sparked the punk flame, but The Clash – most famously made up of Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Nicky “Topper” Headon – fed it, their politically bent lyrics and commitment to social justice setting an early precedent. Their socially conscious songs addressed issues that plagued their London home, like poverty and inequality, but they did so by, at times, implementing images of war and insurrection. While The Clash held a staunchly anti-war outlook, perhaps by viewing these societal struggles through a war-warped lens, the band attempted to emphasize their gravity. “White Riot”, for instance, sounds like calls for a violent uprising; in reality, the shouted anthem decried apathy among the day’s white citizens and their passivity toward the oppression happening around them. Born from witnessing the Notting Hill Carnival riots of 1976 – in which the Black community of West London’s prolonged struggles with over-policing, harassment and brutality came to a head during the district-wide cultural celebration1 – the song urged white youth to take a stand against the establishment too.2 Songs like “Straight to Hell” and “Atom Tan” have always, to me, planted listeners amid conflict as the band uses the aftermath of the Vietnam War and threat of nuclear warfare respectively as vehicles for examining complex topics like immigration and identity to media-induced paranoia or the rising entertainment value of televised destruction.

The Ramones – formed in 1974 in Queens, New York – embraced similar imagery in their overall aesthetic, masquerading as a unit, the foot soldiers of a burgeoning punk army, with Joey, Dee Dee, Johnny, Tommy and members thereafter adopting the Ramone surname. While some early punks donned symbols like swastikas as a means of provocation, they preferred fatigues of ripped jeans and leather jackets. Even still, “Blitzkrieg Bop” – their classic opus from which this book takes its name – references the military tactic, blitzkrieg, or “lightning war”, a method of offensive warfare seeking to defeat opponents in a series of short but violent surprise attacks, in what would become a rallying cry among their fans.

War became an effective tool for many punks; employing symbols of brutality and strife made their messages and issues all the more urgent. These early punks undoubtedly started a cultural revolution, but one in which combat was chic and militancy was trendy. Their music left an indelible mark, but the punks who have endured these real-life hostilities have never needed to borrow such theatrics: they’ve lived them.

Like some of these aforementioned punks, I, too, have never had to survive amidst war or exist under brutal authoritarian rule like those within these pages. I grew up deep in the American South, where my experience was shaped by privilege because of the color of my skin while others have faced systemic discrimination because of theirs.

Growing up in Alabama, an epicenter of the civil rights movement that saw people mobilized against racial segregation and discrimination throughout the 1950s and ’60s, I learned of the freedom songs that became vital to the movement. “We Shall Overcome”, “We Shall Not Be Moved”, “Everybody Wants Freedom” – songs like these inspired bravery, unity and hope among demonstrators who were often met with violence in their fight for equality. In learning about the power of these songs and the courage of those who sang them, I realized music had the capacity to be more than just sounds; it could bring people together, spark revolution. I became fascinated by the genres that channeled this push for change and by those who protested, who stood for – and against – something through music.

When artillery blasts and rifle fire become the backdrop to your everyday, it’s one thing to fight the establishment; it’s another to fight for your life. I will never personally understand what it’s like to experience animosity for simply existing or fathom the immense hardships many have had to endure. I am, however, committed to honoring and sharing the stories of those who have used music’s transformative power to stand up for what they believe in.

Generations of punks have done so, a striking example emerging in Death Pill, the all-female Ukrainian punk outfit. In March 2022, the trio, comprising lead vocalist and guitarist Mariana Navrotskaya, bassist Natalya Seryakova, and drummer Anastasiya Khomenko, released “Расцарапаю Ебало”, which translates as “Scratch Asshole”,3 the accompanying Bandcamp message reading: “We dedicate this release to everyone who defends our country. We are ready to tear the face of every freak who encroaches on our freedom and independence with our manicured nails.”

With the same sobering intensity of their promise, the song gnashes at the ears and claws for the heart. The ferocity of the piercing vocals and the persistence of the battering beat echo the band’s new reality, mirroring the missile strikes, military attacks, and unrelenting siege that became their lives overnight.

Weeks prior, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation”, propagandizing the need “to protect people who have been subjected to abuse and genocide by the Kyiv regime”,4 launching a full-scale invasion of their country, and masking his own ambitions for control of the region. Forces, under Putin’s orders, spilled into neighboring Ukraine from the east, targeting locations near the nation’s capital of Kyiv. “When you’re hearing all these explosions, all these shootings, you really don’t know if you will wake up in the morning,” explains Death Pill’s Khomenko. When we spoke, the conflict was still ravaging their country.

The trio was completing their debut album when the war began. Despite their new reality, they carried on, remastering each previously recorded track to mirror their newborn rage. What began as a rejection of societal pressures forced on young women grew into a stirring oeuvre of strength and resilience.

“Расцарапаю Ебало”, once filled with bite reserved explicitly for an ex-boyfriend, transformed into a pointed message to oppressors, threats to “Scratch your face to fucking blood!” meeting the ear with renewed severity. “Dirty Rotten Youth”, an ominous death march through adolescence, felt even more fury-tinged, proclaiming, “Useless pale life – this is only your choice.” The lyrics of their stinging feminist hymn, “Go Your Way”, grew all the more urgent, cries to “Fight for your respect” ringing out over the frenzied composition, while the vicious anthem “Die for Vietnam” turned all too real amid thrashing strings and visceral wails, warning, “Beware! Napalm’s everywhere!” Their album was released one year after the invasion and has since been re-released with all Russian-language lyrics removed.

As they toured across Europe and the United Kingdom in 2023, they did so with the Ukrainian flag duct taped proudly behind them at every gig. Death Pill’s searing songs became so much more. On stage, they exploded into powerful messages of resistance, with fans shouting “Slava Ukraini” or “Glory to Ukraine”.

Throughout, Death Pill used their music to raise money for Ukrainian armed forces. “They have to kill people,” explains Khomenko of their fellow punks on the frontline. “They have to survive. They have to go through really, really difficult things, and I hate it so fucking much.”

“Now, I hope that all the world realizes what is actually bad, and who is really evil,” notes their bassist. “It’s not punk rockers.”

Over six million Ukrainians have since been displaced, seeking refuge within the battle-scarred region and beyond;5 loved ones have been forced to part ways; and the members of Death Pill were not exempt from such separation.

Khomenko fled to Spain, taking her young son, mother, and nephew to Barcelona. Seryakova found refuge in Australia, settling on the southern coast in Adelaide. Navrotskaya remained in Kyiv, a place that initially avoided Russian seizure but has since faced several attacks. As I write, over two years on, Kyiv just sustained bombardment of its energy infrastructure, Russian missiles having damaged DTEK thermal power plants.6 The war remains ongoing.

Since the dawn of the genre, many bands like Death Pill have chosen to live courageously in times of conflict. Theirs join the multitude of stories in which punks have used their music as a life preserver, turning mere songs into shouts of activism and platforms for change. This book is about those punks. It is also for them.

Blitzkrieg Bops offers a brief history of punks at war, a snapshot across decades, continents, and cultures to understand how they’ve used their craft as a means of resistance and resilience, in the name of change. Rife with stories of those who have soundtracked movements, wielded their music as a daring fist in the face of unimaginable violence, against corrupt governments and tyrannical regimes, this book invites you to bear witness to the reality of what it means to turn to art for survival, when lives and freedoms are on the line. Through these conversations, I hope to illustrate not only the impact of music in times of extreme crisis, but the need for a defiant voice, when an oppressive one is the loudest in the room. I ask, in turn, that you consider the power of these punks’ protests and how their efforts, how these movements can be amplified by us all as many of them – and many more punks to come – continue to fight.

This is Blitzkrieg Bops. These are punks at war.

Chapter 1: 1970s: Dancing on the Corpse of Apartheid

Punk was born when it was needed most. While the 1970s are often stylized as an era awash in the silvery light of disco ball decadence, it was also marked by instability, which cast a bleak pall over both the United Kingdom and the United States.

After years of relative prosperity following the Second World War, the two Western nations experienced a combination of economic stagnation and rising inflation.7 Where the cost of living spiked – food and energy prices accelerated dramatically – employment dwindled, with both nations seeing 5-6% of their labor forces out of work by 1979.89

This economic turbulence stemmed from a revolv-ing door of incidents like the 1973 oil crisis, in which the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries implemented an oil embargo against those who supported Israel during the Fourth Arab-Israeli War,10 and the subsequent 1979 energy crisis, where a roughly 7% drop in oil production in the wake of the Iranian revolution caused global knock-on impacts.11 Labor strikes were frequent, especially between coal miners and steel workers, as strains were felt from the move toward deindustrialization. The decade saw also dramatic changes in leadership. Where U.S. citizens saw faith tested with President Richard Nixon’s resignation following the Watergate scandal, Britain saw Margaret Thatcher take the helm of the Conservative Party with numerous controversial policies.

The world was changing as the Vietnam War waged on and various movements sought to shape the future. Despite advancements made during the civil rights movement, Black citizens continued their fight against discrimination, especially in the workforce and education.12 The Stonewall Riots of 1969 stirred greater political activism for LGBTQ+ rights, leading to the formation of global organizations, like the Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance.13 During this time, women demanded equal pay, an end to employment discrimination and autonomy over their bodies and reproductive rights.14 There was promise of change on the horizon, however, that promise was often met with disillusionment over this surmounting inequality in regards to race, class, sexuality, and gender.

Punk music would become the perfect outlet for the era’s youth to roar their discontent. Flinging their frustrations at authority and the establishment, punks created their own social and political commentary through music. Struggling with the imposing classism? The Sex Pistols called for “Anarchy in the U.K.”. Feeling alienated by society? The Ramones commiserated with “Teenage Lobotomy”. Pointed songs and abrasive style was used to upend the norm, making collective hardships more bearable.