3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

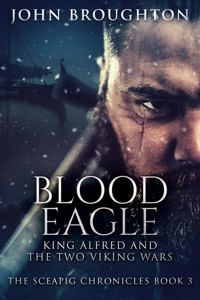

The Vikings are poised to return to Sceapig, ready to raid and pillage the small island.

Best friends Deormund and Faruin, born and raised on Sceapig, are rebuilding their lives with one goal: how to retake the island for the Saxons. After meeting the young Aetheling Alfred, the two young men are rewarded with status and power by King Alfred, and become his chief advisers as the Vikings threaten to overwhelm all England.

Risking his life to expand Wessex into one perfect Saxon kingdom, Alfred is only too aware of the horrific fate of King Aella of Northumbria, who met his end by the Viking torture method known as the blood eagle. Can the three succeed in their plans, and what price will they have to pay to realize their dreams?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

BLOOD EAGLE

THE SCEAPIG CHRONICLES BOOK 3

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Frontspiece

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Epilogue

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2021 by Next Chapter

Published 2021 by Next Chapter

Edited by Chelsey Heller

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

PREFACE

Sceapig Isle, Kingdom of Kent, 854 AD

Ealdorman Raedulf ordered his men to spread oil over the decks and barrels of the Norse longship. The thought of burning the sleek vessel saddened him but, after careful consideration, it was better to destroy it than recapture it, and let it be used once more against the Saxons.

Despite their after-battle weariness, Raedulf’s willing troops gathered up the bodies of their foes and, two-to-a-corpse, heaved them aboard the stranded ship. The ealdorman had accounted for five of the slain Vikings, so well had he wielded his father’s and grandfather’s sword, which was, ironically, a Viking blade inscribed with the Runes of Victory. None of the three men had brandished the precious weapon in defeat, although they had used it twice in Saxon defeats. The last time had been two years after his father’s death, last year, when another of the victors of the naval battle of Sondwic, Earl Ealhhere, fell with men of Kent and Surrey in a hard-fought engagement on the Isle of Thanet. Raedulf had survived the fighting thanks to his quick wits and boldness, so the sword his grandfather had taken from the Viking chieftain he had slain with a slingshot was still his to fight with another day, after this minor but significant victory.

All the Viking bodies were aboard the craft. Because he hated to see the destruction of what he considered a work of art—since his childhood, he had loved ships—he sorrowfully ordered the torching of the vessel. He remained in Minster Bay long enough to ensure that the conflagration would indeed consume the corpses and their vessel alike. With a sinking heart, he watched the gaudy paint blister on the carved dragon figurehead at the prow and the greedy flames devour the snarling creature’s head so that for only a moment, the ferocious beast seemed to launch flames from its mouth like a mythical beast. Raedulf turned away with mixed feelings before proceeding to help carry the Saxon dead, all ten of them, uphill to the abbey, where they would receive a Christian burial and be laid to rest in the same graveyard as the ealdorman’s illustrious forebears.

As they toiled up the narrow trail to the Minster, black smoke billowing from the beach behind them, Raedulf reflected on the day’s events. First, the alarm blaring from the watchtower, then the tense wait to ambush the raiders, at the cost of sacrificing innocent outlying islanders. It was only one of the difficult decisions he would have to make that day. As he knew they would, the Danes had followed this selfsame trail leading to the abbey. Monasteries and convents were their preferred soft targets, where silver and jewels could be found unguarded by warriors and were thus easy pickings. The insatiable raiders little suspected that from out of the undergrowth would spring a force of battle-hardened Saxons, dealing death and routing them back to the beach. There, the wrathful Vikings had formed into a defensive wall, but Raedulf’s men outnumbered them and, at the cost of ten of their company, slaughtered thrice the number of raiders to the last man.

Ay, survival on Sceapig is coming down to a question of numbers, Raedulf thought sadly as they entered the abbey gates. I have a lot of persuading to do as soon as the burials are over.

The first person to be persuaded had to be himself because he loved Sceapig and felt his roots were there. But circumstances were driving him away. His foresight in repairing the hall in Rochester—for he was Ealdorman of Rochester—would be repaid. The Vikings had burnt the building back in 842 when his father, Asculf, had feared for his and his mother’s lives. The town walls had resisted the Norsemen, but a betrayal had let them enter by a postern gate. The slaughter, devastation and looting had been typical of the merciless and rapacious Sea Wolves: the scourge of the age.

After the disaster and the joyful reunion with his family on Sceapig, Ealdorman Asculf chose to reside in the hall his father, Deormund, had built on the isle. Apart from his ealdormanry duties—such as witans, levies and so forth—Raedulf had stuck by this decision. Only now, the time had come to abandon their island home even if his son, the fourteen-year-old Deormund, named after his great-grandfather, loved the island and its beaches. The boy had followed the same arduous training in swordsmanship and weaponry as himself and his father. An ealdorman and a potential successor had to uphold the family tradition of excelling in the martial arts. Young Deormund was as fine a swordsman as any of his predecessors. Today, his father had to mollify him—for he wanted to fight the Danes by his side—by insisting that he stay in the hall to defend his mother, if need be, with his life. In truth, Raedulf knew that his swordsmanship was superb, but the youth’s frame needed to fill out before he could face a muscular Viking warrior.

Back in the hall, he had to cope with his son’s excited questions about the battle before instructing him to fetch his mother, as they would go to the abbey together to speak with Abbess Disburh. He refused to tell either his wife or son why he sought audience with the Mother Superior. Their presence was only necessary to save him from repeating his argument—the same that he must sadly relate to the abbess.

“The island is depopulated; the outlying farmsteads are heaps of ashes, and there is no sign of these continual raids relenting. I do not have enough men to garrison Minster. We lost another ten warriors today, Mother. What I am saying is that I must take my men to Rochester and leave you and the sisters undefended—”

“You can’t do that, father! I will stay and head the detachment.”

Before Raedulf, whose face had clouded into a thunderous expression, could speak, the elderly abbess, successor to the saintly Abbess Irma these last ten years, raised her hand.

“My son,” she addressed the chestnut-haired youth, “whilst I admire your undoubted valour, it is your duty to heed your father. Do you not see how it pains him to make this decision? A son must obey his father, just as Our Lord did his Father’s will and let himself be nailed to a tree. Say no more!” she scolded as he opened his mouth to protest.

Deormund hung his head and glowered at the paving stones.

“You should come to Rochester and bring the sisters with you, Mother,” Raedulf said. “I will build you an abbey there. As you know, Justus founded the diocese, one of the missionaries who accompanied Saint Augustine to Kent, to convert the pagan southern English to Christianity over two hundred years ago. You and the nuns will be able to use the sacred cathedral where Saint Paulinus is buried in the sanctuary of the Blessed Apostle Andrew, which King Æthelberht founded when he built the city of Rochester.”

Disburh smiled sweetly and, pursing her lips, paused before saying, “You speak knowledgably and persuasively, Ealdorman, but just as your son must obey you, so must I defer to my Father in Heaven. I cannot take this decision lightly here and now. I must pray to seek God’s will for us; only then, when my prayers are answered, shall I decide.”

“Mother, never forget the wrath of the pagans; you have a responsibility for the souls in your charge.”

“Our prayers will protect us if it is God’s will, my son.”

Outside the abbey, safely out of earshot, Raedulf gave vent to his pent-up anger.

“The foolish old woman! How can prayers shield her from a Viking blade?”

His wife took his arm and spoke steadily, “Do not fret, husband, Abbess Disburh is an intelligent and pious woman. Your words were not wasted, but she must address her thoughts to the Lord. She will come, you’ll see. As for me, I’ll feel safer inside the walls of Rochester, and,” she added with a relieved tone—"I’ll feel more relaxed about you and Deormund, too.”

“Don’t worry about me, mother,” Deormund growled. “I’ll miss Sceapig. I don’t want to go to Rochester!”

For fear it would sound childish, he did not wish to explain why. The truth was, he did not wish to leave behind his inseparable boyhood companion, Faruin—like a brother to him. Who would he explore and hunt with in a town?

“There’s a fine smith I know in the city,” Raedulf said to his son. “It’s about time you had your own sword. I was at least two winters younger than you when I got mine. Oh, and you know that hound you’ve been nagging me about? You’ll be able to walk him along the banks of the Medway.”

“A hound and a sword, father? If you swear it, I’ll come to Rochester willingly.”

Both parents laughed, and Raedulf made the vow.

ONE

Sceapig Isle, Kingdom of Kent, 855 AD

Amid the forest on the Ness, Faruin cursed under his breath; hunting was so much easier in pairs, with one to rouse up the game and the other make the kill. Now that he was alone—Deormund was in Rochester—he had wasted the morning.

Just as he despaired of returning home to Minster without anything for the pot, he froze. Was that a partridge foraging in the undergrowth? Moving his arm stealthily, he nocked his arrow, took careful aim, only for the fowl, as if by a sixth sense, to make its ungainly flight towards the edge of the trees. Cursing again, but not to be dissuaded so near to his prey, Faruin moved silently, despite his lanky frame.

Drawing back his bowstring, he made no mistake this time. Years of competition with Deormund, aiming at targets no more extensive than the palm of a hand, repaid him as the arrow struck true, transfixing the partridge. His mother would praise him to the heavens this day! In three giant strides, he reached the bird, bent to work free his arrow—no sense in wasting a good shaft—grunted his approval at the size of the creature, plenty of flesh on this one, straightened and froze again. This time, he had not spotted another prey, but rather, he was the quarry.

From his vantage point among the fringe of trees at the edge of the forest, he gazed, mouth agape, upon the sparkling sea. The cause of his astonishment was another forest rising from the waves—one formed by masts, each with a billowing sail driving forward a longship. Vikings! There were too many for him to count, and they were, without doubt, heading for Sceapig. Bow in one hand and partridge in the other, he hissed an oath, not for the first time that morning. Why had he wandered so far from Minster? Now he would have to run home to warn the islanders of the approaching peril.

Risking a painful fall, he flew down the track to the meadow, only slowing his pace when he turned his ankle in a rut likely left by the weight of a barrow filled with firewood. Luckily, the twist of his foot was not severe enough to stop him from proceeding, but he decided to run at a more moderate speed; he could accelerate as soon as he reached the meadow.

Once across the meadow, gazing over his shoulder to check that the Norsemen were still on course for Sceapig—they were—he sped up the well-worn trail towards the settlement that contained the abbey, the hall and the small group of houses, including his parents’ home. He did not run to his home but took the steps of the watchtower two at a time, hardly breaking breath because his wiry physique and active outdoor life meant he was as fit as a young stag. Knowing that the alarm horn hung from a chain attached to the wooden tower ramparts, he peered over and gasped at the sight of so many sails, each boasting a giant emblem—mostly of black birds like ravens in different attitudes—so close now to the shores of the isle.

There was no watchman because since Ealdorman Raedulf had left with the majority of the menfolk, the island was reduced to less than a score of ceorls to work the fields. Faruin’s father was one of these: the stubborn fool! Why had he refused to leave Sceapig? Thanks to his hunting skills, the morning that should have been joyous was transforming into one of curses and regrets. He had begged his father to depart from Sceapig for Rochester, only to meet with a sullen refusal. Sceapig is my home and a pack of heathens will not drive me out. Well, that pack was here now!

Faruin raised the horn to his lips and blew the traditional three blasts. The effect was immediate as five men raced into the courtyard to stare up at him.

“What’s up, lad?” Eggert, the wheelwright, shouted.

“Viking ships! Hundreds of them! Warn my father and the other men in the east field, and close and bar the gates.” He coughed because his raised voice had become squeaky. Unlike Deormund’s, his voice hadn’t broken yet. It was so unfair! He was several months older than his best friend, who now boasted a rich, deep voice. When you had a voice like that, people respected you. Still, he gazed down with satisfaction at grown men scrambling to do his bidding. Yet, he thought fearfully, to what purpose? How could a score of Saxon ceorls resist a whole army of Vikings?

He peered over the parapet. The nearest longship was a matter of minutes from beaching in Minster Bay. No time to lose! He rushed down the steps, taking them three at a time, to dash across the courtyard to his family’s house.

Bursting into the smoky room, where his mother was chopping carrots to throw into the iron pot hanging from a bar suspended over the fire, he earned himself a scolding.

“That’s no way to come in! I could have sliced off a finger from the shock you gave me!” She turned to look at her son and waved the small knife threateningly, in complete contrast to the loving expression on her tired, lived-in face. Linveig’s was a hard life, and it pained him to give her the bad news, but he must. He flung the partridge onto the table.

“I don’t know if we’ll ever get to eat that!” he exclaimed.

There was something in his bearing and tone that alarmed her.

“What is it, Faruin? I thought I heard the warning horn.”

“Ay, you did, mother. It was I who blew it. The Vikings are here. Make ready; we must leave the isle.”

“I’ll not go without your father.”

Faruin breathed deeply. Stubborn parents were his curse. If they left now, with all haste, he knew the quickest way to the ferry across the Swale and they could flee with their skins intact. If she stayed, what would happen? He squeezed his eyes closed, not daring to imagine her fate.

“Mother, I beg you! We have only a few minutes to escape. Don’t you realise what the heathens will do to you? They are not men—they are fiends straight from hell!” He was unsure whether he was exaggerating, but he needed to scare her out of her stubbornness. She was wavering; he saw it in her eyes when the door burst open. Startled, she screamed, fearing Viking raiders, but it was only her husband.

“Oh, Eolf, it is you!”

“Who else would it be, woman?”

“I feared it was a Viking.”

“No Viking will ever set foot in my home.”

“Oh, and how do you mean to stop them? Three cats against a Norse army!” Faruin sneered.

Eolf stepped closer to his son, his face contorted with rage at his son’s disrespect.

“They’ll not get past the gates; we’ll fight them off.”

“Well, I’m away to Rochester, and I’m taking mother with—”

He did not finish because a thumping blow to the side of the head sent him crashing to the floor as the room turned black.

Later, his mother was fussing over him, dabbing a damp cloth to his right temple when he came to. His stomach clenched, and he felt sick, but groaning first, he managed, “Where is he?”

“Out on the gate tower, shooting down on the Vikings. They’ll soon break in,” she said fearfully.

Faruin rose unsteadily, his head splitting.

“Come, mother, we must go.”

“How can we? The Vikings are at the gate.”

“Trust me. I know a secret way out.”

“I’ll not leave your father. I’ll be a widow.”

“Ay, and I’ll be an orphan. Hark, mother, if leaving the abbey with her nuns for fear of the Vikings was good enough for Abbess Disburh, it’s good enough for you! I’m only fourteen years old with my life ahead of me. Why should I die for a stubborn fool who cares nought for me, and never has?”

“That’s not true. Your father loves you.”

“He has a strange way of showing it! And you, mother, do you love me enough to come with me, or are you going to wait for the heathen to rape you and slit your throat when they’ve done with you?”

She looked shocked at his crude words, but then said almost in a whisper, “Thank God the Abbess heeded the ealdorman’s advice. Ay, I’ll come.” She paused only to find her pendant cross, pulling it over her head and kissed the wooden symbol. She smiled sadly. Looking around her kitchen, perhaps for the last time, she said, “I’m ready, son.”

He opened the door a crack to check that nobody was in the courtyard to see them leave. The only witness was a scabrous dog, scratching itself with its hind paw.

“Come on,” he said, taking her hand and leading her close to the wall of the ealdorman’s hall. They advanced in its shadow to the far corner, turned, and headed to the hen coop. The hens clucked and scratched the earth, but he did not spare them a second glance, leading his mother behind the enclosed pen. There, he knew, was an ancient fox tunnel that nobody had bothered to fill in. He and Deormund had used it whenever they wanted to come and go unseen from Minster. With a reassuring look to his mother, he wriggled through with expert ease, first ensuring that there were no Vikings in sight in either direction, even if he could hear their clamour from around the palisade at the gates.

“Come on!” he called to her from the hole. He was relieved moments later when his mother’s head appeared. He grabbed her under her armpits and hauled her to her feet. “Now we run!” he said, pointing to the woods about fifty yards from where they stood.

She surprised him by taking off into a sprint, hauling her dress as she ran till it came to her knees. Once into the trees, she turned to him, red-faced, giggling like a girl. “I’ll wager you didn’t think I could run.”

“From now on, no talking. If I wave like this, go down on your haunches, clear?”

She nodded and looked lovingly at her son, grown into a man. It only seemed like yesterday when he was born. Now he was the man of the family whilst his father threw his life away in a hopeless cause. She wiped a tearful eye and obediently followed her gangly boy with the trace of down on his cheeks along the track.

He halted and after a few minutes, he waved. She crouched down, as instructed, her heart thumping. Moments later, he was helping her to her feet and complaining, “Trust my luck! A red deer hind, wouldn’t you know it when I’m not out hunting?”

She sighed with relief and did not relax until the trees ended, and they crossed rapidly into a reed bed.

“We’re safe now,” he whispered, “even if there are Vikings around, I know this marsh as well as you know your kitchen. Fifty yards that way is the ferry.” He pointed.

Startling many species of wading birds, he grumbled occasionally, repeating that he wasn’t out hunting, whilst she smiled at remembered days of him returning with his usual proud flourish as he tossed a duck or once, remarkably, a wild goose, onto the kitchen table. What a feast that fowl had made!

They moved slowly, placing their feet with care; she copied him, knowing that one mistake could plunge her into the quagmire until Faruin turned around and grinned. “Firm ground—we’ve made it to the crossing point.”

He led her swiftly onto a grassy bank, where she saw the boatman’s tiny house, fishing nets hanging from a nail in the wall. Normund the ferryman had taken over the job since the Danes had murdered his popular predecessor. Now Normund appeared, alerted by voices. He was a sturdy figure, seemingly too huge to pass through the low door of his house.

The boatman’s friendly, ever-present grin ensured that he was well on his way to matching the unfortunate Helmdag for popularity. Of course, Faruin had never known the legendary ferryman, who had died before he was born, but many tales persisted about him to the present day.

“You’ll be wanting to cross the Swale, young sir, unless I’m mistaken.”

“Ay, Master Normund, if you’ll be so kind. We’re fleeing the Vikings. I’m on my way to warn Ealdorman Raedulf. You’d be well-advised to come with us to Rochester.”

“Vikings, you say? Are there many of them?”

“I lost count of their ships. Now they are besieging the hall.”

“My God! There’s no one left on Sceapig to defend it.”

“There’s my husband,” Linveig said, her tone defiant.

The boatman gazed at her pityingly; he knew there was no hope against so many Norse crewmen. For her part, she stared at the rushing Swale anxiously as Normund helped her into the boat. She had never before crossed it, having spent her whole life on the isle, often wondering what lay beyond its confines. Today, she would see a city! Minster was the most extensive settlement she had ever known, and even when Sceapig was populated, it had boasted no more than fifty dwellings, not counting the abbey. She was most definitely on an adventure, but her brow furrowed as she thought of Eolf battling for his life. Oh, why hadn’t he heeded the ealdorman’s plea to take their small family to Rochester? she thought. Faruin, who was now chatting cheerfully with the ferryman, had begged his father, too, but had always received the same gruff reply—no heathen’s going to drive me from my home.

That would be a proud boast the stubborn man would take to an early grave. Involuntarily, she looked back at the bank they had left, rather than the one the small vessel was now nosing towards—what, for her, was the land of promised adventure.

She expected Normund to help her out, but it was Faruin’s hand that reached for her. Incredibly, considering the shadow of the Viking threat, the boatman remained sitting, holding his oars.

“Push her off, lad!” he called cheerily.

“Aren’t you coming, Master? What about the Vikings?”

“Nay, I’ll stay. I’ll hide in the reed bed, if necessary. You never know; I might have to bring good Sceapig folk to safety. You go and tell the ealdorman what’s going on.”

“Take care!” Faruin yelled as he shoved the bows away from the bank. “He’ll get himself slain,” he said in a much lower aside to his mother.

“Do you think some folk might escape?” Linveig asked hopefully.

The youth put his arm around his mother’s shoulder and pulling her to him—she was a head shorter than he— he said gently, “Father cannot escape; the last men of Minster may well all be dead by now,” he murmured, convinced it would be crueller to give her false hope. “Try not to think about it. We have a new life ahead, and it’s a three-league walk to get to Rochester—at least, that’s how far Deormund said it was from here. We should follow the path towards the sun. He said it was due west of the ferry.”

“I’ve never been off Sceapig,” she said, eyes wide, “so I can’t help you with directions.”

“What?” he said, “Not once in all your life?”

She mock-struck him on the arm. “All my life? You make me sound like an old woman!”

“You are old, mother. Ouch! That hurt!”

She laughed gaily like a young girl, momentarily forgetting her worries. It would be exciting to see the city, and it was too soon for her to ask herself what she and her son would do to survive there.

TWO

Rochester, Kingdom of Kent, 855 AD

Faruin and Linveig saw and smelt the city much at the same time. The south-westerly breeze carried the predominant aroma of woodsmoke, mingled with far less pleasant and indefinable odours. The town’s ancient walls coiled like a long, brown snake across the flat landscape of their approach. Off to its right, as they gazed, the Medway shimmered in the sun, intersected by a fortified bridge.

“Faruin?”

“Ay, mother?”

She frowned and bit her lip. Now that they were near enough to see the imposing walls of brownish mortar ragged with pebbles and broken flint, the reality of their situation had hit her. She stared at the formidable gate tower and experienced a succession of mixed emotions. She was also racked by uncertainty, recognising that they would be far safer there from the heathen menace than in any exposed village.

Her lower lip trembled. “What shall we do for a roof over our heads? And food? We have no money.”

“Our first task is to seek out the ealdorman. I’ll speak with him.”

A cart laden with hay bales preceded them to the gate, and a bored guard waved the ceorl and his ox through. The guard stared hard at mother and son. “Who are you? Haven’t seen you two before.”

Faruin stepped forward. “I’m a friend of the ealdorman’s son Deormund, from Sceapig, and this is my mother. I have an urgent message for the ealdorman. And you’re right,” he wanted to mollify the suspicious guard, “you haven’t seen us before because this is our first visit to Rochester.”

The sentry’s expression changed to a friendlier demeanour.

“In that case, I’d better give you directions to the hall, but be warned—you might have more difficulty getting past the guard on the door there. I can’t resist a pretty face; that’s my weakness.” He beamed at Linveig, who bobbed a dainty curtsey and giggled. Pleased with himself, the fellow took Faruin under the arm, led him through the gate, and pointed straight along the main street, which they were to follow until they reached a horse trough, where they should turn to the right. It would be impossible to miss the hall, as it was the most prominent building with a sentry at the door.

They thanked the obliging custodian and set off, taking care how to place their feet, trying to avoid foul excrement and suspicious-looking puddles.

“I hope the people of Rochester are all as friendly and helpful as he,” Linveig said, appearing less anxious and much taken by her surroundings. She had never seen such bustle and smelt so many intermingled odours. Some were pleasant, like the aroma of freshly baked bread as she passed an open door; others vile, principally from the road that occasionally resembled the cesspit in Minster, which made her wrinkle her nose and frown.

“There are so many houses and different streets,” she murmured.

“Ay, they say Canterbury is even bigger than Rochester,” Faruin offered.

“Goodness knows how many acres these walls enclose.”

“I’ll make it my business to find out. Deormund told me that the Romans built them. They named this city Durobrivae, he said.”

“Duro-briv-ee?” she mouthed the unfamiliar name hesitantly.

“Ay, that’s right. So you see, this enclosure has stood the test of time; it’s been here for hundreds of years, mother. We’ll be safe enough inside these walls.”

“That is, if we can find a home and food to keep body and soul together,” she murmured.

“Don’t worry. If the worst comes to the worst, you can throw yourself on the mercy of Abbess Disburh.”

“Would you have your mother become a nun?”

“Many widows do.”

“Ay, but I’m not a widow, am I?”

He did not wish to plunge her into despair, so he took her hand and said boldly, “Of course not, you’re right. The Vikings might not have entered the hall courtyard.” But in his heart, he knew the likelihood of that was negligible. In his mind, his father was dead. Strangely, he relished the idea of caring for his mother. One thing was sure: he never had cared for his father, who had always been too handy with his fists; his father had also occasionally used those fists on his mother.

The hall was an impressive construction, as was the guard by the door.

“And I’m telling you that the ealdorman isn’t here. If you must know, he’s gone to Canterbury on important business. Now, be off, the pair of you!”

The ferocious expression should have been enough to scare anyone, but Faruin persisted. “I’m a friend of Deormund, the ealdorman’s son. At least, let me see him, please.”

The guard looked over the spindly youth and considered that he might be telling the truth, despite the height difference, given the youth’s squeaky voice and downy cheeks. He relented his hostility and smiled. “Ay, a friend you might well be, but he ain’t at home, either.”

“Why, has he gone to Canterbury, too?” He couldn’t hide the disappointment in his voice.

“Nay, unless he means to walk his hound that far.” The guard chortled at his joke.

“Hound? Does he have a dog?”

“Well, let’s say it has four paws, a tail, and a long, lolloping tongue—does that sound like a hound to you?” He bellowed with laughter again. “Hey, you’re not going, are you? I was enjoying our little chat.” His roars of laughter followed the gangling youth across the road to where his mother waited for him.

“Well?”

“The ealdorman is in Canterbury. We’ll have to bide our time and wait for Deormund to come back with his hound. He’ll help us out, I’m sure.”

“We can’t just stand here, Faruin.”

“Why not?”

Her lower lip trembled, and her eyes filled with tears that threatened to spill down her cheeks.

“Because my legs ache, I’m tired, and I’m hungry.”

“Is that all? Well, we’ll soon see to that, come on!”

The tears did not flow. Linveig sniffed and murmured, “Is that all?” She thought it was more than enough, but he led her to a nearby inn that he must have noticed when they’d passed earlier.

“But we have no money,” she protested.

“We do. I stole it from father’s hideaway before we left. I figured he’d not need his stash when the Vikings finished him off.”

“Oh, Faruin! What stash?”

“This!” He flourished a small leather purse under her nose. “He hid it in a nook behind the doorpost. It’s money he got from selling stolen grain. I saw him tucking coins away when he thought I was sleeping. Now, are we going into this tavern or not?”

“Eolf would never steal!”

“That shows how little you know about your husband. Mother, you shouldn’t mourn him. He’s no loss!”

“Your father’s a good man.”

“Is that why he split your lip a month ago?”

“That was my fault for answering back. My tongue ever gets me into trouble.”

Faruin snorted, exasperated. Gently pressing his hand into the small of her back, he steered her through the inn door.

Wiping her bowl so as not to waste the last drops of the delicious eel soup, Linveig looked adoringly under her long lashes at her son. What a wonderful feeling to have a man she could count on. He called for two beakers of ale.

“Your very best, mind, landlord,” he squeaked. The innkeeper considered him the most unlikely seasoned drinker he had ever seen in his hostelry. Nothing surprised him these days; he’d seen it all in his time, he reflected, even a callow youth with a mistress twice his age! She was attractive, too, if a bit tired-looking. Maybe her young lover had kept her awake all night, but it was none of his business. Anyway, the young ram’s silver piece was good; he’d bitten it to make sure.

Linveig was partial to a good ale, so, as the rotund host set hers down, she said, “Thank you, son,” and smiled at the youth, causing the landlord almost to spill Faruin’s as he set it down.

“Is he your boy then? You don’t look old enough to have a son as tall as that.”

“I’ll take that as a pretty compliment, mine host,” she beamed at him, eliciting a grin as he slid Faruin’s coin back across the table. “This one’s on the house,” he said, sauntering away, pleased that his unworthy suppositions were wrong. Besides, the lad had asked for a room, so there’d be more silver later. Best to treat good customers well, he smiled to himself.

“Mother, I’ve taken a room. Why don’t you have a lie-down whilst I go to seek out Deormund?”

He led her over to the innkeeper, exchanged a few words, and handed over two silver coins before following the puffing landlord and his mother up the narrow stairs. If the room weren’t good enough, the fat man would feel the point of his knife at his triple chin, and he’d claim their money back! Luckily, the room was clean and tidy for a city centre inn—Faruin guessed that there was little custom for rooms or the landlord employed a good cleaning woman. Either way, he was so relieved, he expressed his pleasure.

“This will do very well, landlord; you keep a fine house.”

“Thank you, kindly, young sir, I’m glad you approve.” The portly man gave an ungainly bow.

Faruin waited for him to go and ensured his mother was comfortable; her eyes were already closed before he slipped out as silently as a ghost. Back on the street, he smiled inwardly, content in his role as protector, but he was under no illusion that his father’s ill-gotten gains would last for no more than a few days. This thought so lengthened his notable stride that he soon reached the grinning guard.