4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

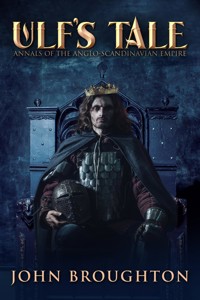

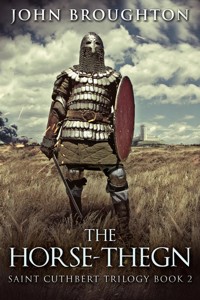

It's the late 9th century, and Northumbria is subject to both Viking attacks and settlers from Denmark.

Cynn is the royal Horse-Thegn. Striving for peace and integration on his estates, he is charged by the king to end the pillaging of a foul band of raiders. Led by the elusive Edred, their atrocities have become increasingly violent, resulting in open revolt against legitimate rule.

But in the face of many external threats, can Cynn achieve his aim of a durable and prosperous kingdom, as they enter a new century?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE HORSE-THEGN— TALE OF AN ANGLO-SAXON HORSE-THEGN IN NORTHUMBRIA

ST CUTHBERT TRILOGY, BOOK 2

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 by John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Apart from known historical figures, names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination. Other than actual events, locales, or persons, again the events are fictitious.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Frontispiece: Runic inscription on the Bewcastle Cross reproduced by Dawn Burgoyne

Medieval re-enactor/presenter specialising in period scripts. Visit her on Facebook at dawnburgoynepresents.

The Horse-thegn is dedicated to anyone who cares for horses.

Special thanks go to my dear friend John Bentley for his steadfast and indefatigable support. His content checking and suggestions have made an invaluable contribution to

The Horse-thegn.

ONE

BAMBURGH, NORTHUMBRIA, MARCH 867 AD

Unfortunately, we cannot choose when or where we are born. My misfortune was to come to the light in the darkest days of our kingdom. The Northumbrians had violently expelled the rightful king from the land, Osbert by name, and placed on the throne a tyrant, Aella. When the pagan Vikings descended upon the land, the dissension was allayed by Church counsellors with the aid of the nobles. King Osbert and Aella, having united their forces and formed an army, came to the city of York.

When the savage shipmen joined in a wall before us, battering their weapons on their gaudily-painted round shields, I ordered my men to secure the horses at our rear so that we could engage on foot. The enemy fought as ferociously as half-starved wolves; nonetheless, we broke their shield-wall and drove them back in a rout. We Christians, perceiving their flight and terror, found that we were the stronger. That is when I seized glory, leading the horses in pursuit, and I swear that more of the enemy died, hacked from behind by our mill-sharp blades, than those we dispatched to their Valhalla face to face. We forced our way through the ill-repaired walls of the city but with each side fighting with unrestrained ferocity, both our kings and eight ealdormen fell. Without a recognised leader, our nobles bought peace.

I am Cynn Edwysson, horse thegn, descended from four generations of officials holding this prestigious rank. The first, my father’s grandsire, whose name he bore, was granted his position by King Aldfrith of great renown. Edwy’s father, Aella, who bred steeds in Ireland began the family tradition of rearing horses; but I digress.

Although I wished to drive home our slight advantage, the sheer might of the Viking fleet anchored off our coast under Halfdan Ragnarsson, intimidated our surviving ealdormen. That is why I find myself horse thegn to a tributary king, Egbert by name, who is forced to raise taxes and enforce the will of the ravenous Danes. When I think of his feeble subservience my blood boils, and I am not the only warrior to harbour this sentiment.

Yesterday, my younger brother, Galan, born while I was watching the snowfall wide-eyed with wonder in my second winter, crossed the causeway from Lindisfarne to seek me out and say his farewells. Galan is a monk, more precisely a scribe, just like our famous forebear, Aella—the friend of our beloved saint, Cuthbert. The reason for Galan’s departure was motivated by our deep love for the saint, and Bishop Eardwulf, in consultation with Abbot Eadred of Carlisle, made a crucial decision in this regard. These prominent churchmen, aware of Halfdan’s fleet anchored in the mouth of the River Team, remembered what had happened more than four-score winters past when, in January 793, the Norsemen sacked Lindisfarne Abbey, slaying or enslaving the monks and plundering the monastery treasures. Miraculously, the grave of the sainted Cuthbert remained unharmed. The two dignitaries were not prepared to take the risk of desecration on this occasion, with the Vikings lurking offshore and preparing to descend on Northumbria like wolves on a sheep pen.

The high-ranking clergymen ordered the digging up of the saint’s body, incorrupt—the Lord be praised! —his ceremonial vestments still covering him. With awe and care, his remains were placed in a coffin with the head of Saint Oswald, martyr, and the bones of Saint Alban and other saints. Just seven monks were allocated the task of transporting the coffin to safety, away from the coast, and among these, was my brother.

Having bid me farewell, he departed with his companions taking the old Roman road towards Corbridge, bearing the box on their shoulders. What a long and arduous journey lay before them, they who had to preserve their precious burden at all costs and who could travel little more than a league-and-a-half a day.

I found myself in a difficulty. What were my choices? Should I remain faithful to an unworthy king or follow my brother and seek to protect the relics of the most venerated servant of God to have ever trodden the ground of our beloved Northumbria? Given the inevitable slowness of the monks’ procession, I resolved to wait and see what the Danes would decide.

At this point, I should explain that such was the general devotion to Saint Cuthbert in Northumbria that the people of this land became known as the haliwerfolc or ‘people of the saint’. I share this reverence, not least for family reasons, as I mentioned previously, our great-great-great grandsire was a close friend and, later, chronicler of Cuthbert. There was a belief among us descendants that Aella made the binding of the volume known as Cuthbert’s Gospel and that the book was buried with his body. I forgot to ask Galan if it had been found when they dug up the remains. When we meet again, I’ll be sure to enquire.

Having installed a puppet to do their will in Northumbria, the Danes felt confident enough to move south for the richer pickings offered by the kingdom of Mercia. News reached Bamburgh that the Vikings had taken Nottingham and that they were organising overwintering there.

As the royal horse thegn, I was a member of the king’s council. This was an unhappy function in those dark days. One of the least powerful of the assembly, I mostly remained silent because it would have been easy to be expelled, or worse if I voiced my headstrong opinions.

I had to countenance the excessive taxation mooted which the spineless Egbert duly poured into the Norse coffers regardless of the suffering of our people. Were the rigours of the winter not a sufficient burden for the ceorls to bear without such an imposition? As a silent onlooker, I identified the minority of ealdormen who shared my opinions. Chief among them was a powerful and outspoken man of royal blood, Ricsige. It was too early to openly support him, but I bore him in mind as a potential ally should the situation deteriorate further.

Months had elapsed since the departure of the seven monks with Cuthbert’s remains, and with the harsh months looming, I worried about their progress and health. Having already supervised the stockpiling of winter fodder for the horses, given instructions to manage breeding and sent traders to Frankia for the purchase of five war steeds of Spanish bloodline for the brood mares, there was no reason for me to linger in Bamburgh. I could not leave without Egbert’s permission, but likely he saw me as of little value owing to my silence in the moot. Bishop Eardwulf, upon hearing that I intended to assure the safety of the Cuthbert bearers lent his considerable weight to my plea. The king conceded five horsemen to accompany me and I, of course, chose them from among my friends.

We discovered their trail with little difficulty because I knew they had made for Corbridge. Enquiries in that town gave us a surprise because instead of proceeding west as originally planned, the monks decided to cross the Tyne and head for Norham. We rode to that town and the people remembered the strange procession well, for they had received them with open hearts. Everyone we spoke to told us of the great honour felt to have the saint among them, however briefly. Well-wishers offered food, shelter and even precious gifts to the weary travellers. Some wished to shoulder the burden but this was not permitted as only the seven bearers were allowed to touch the coffin.

For reasons we could not discover, the monks did not cross the River Tweed, perhaps fearing the Picts, who can say? Instead, they veered southwest to Tillmouth, whence they proceeded to a place named Cornhill. In both places, we found the same awed response to the passing of Cuthbert. Thence they trudged along by the course of the Tweed and, I, on horseback, devouring the leagues, felt my heart ache for their poor weary bodies, which somehow, they had dragged as far as Wark. It was there that we learnt of the monks’ intention to plod on to Melrose Abbey because among the bones in the coffin were those of Saint Aidan, who had appeared in a dream, begging the sleeping monk to take him to the monastery that he had founded many lifetimes before. In the same dream, the saint instructed them to spend the winter in the abbey, where they would be well received and might recover their strength.

This news pleased me on behalf of my brother, whose wellbeing concerned me. On the way, we stayed overnight in an inn at a settlement called Dryburgh before resuming our journey to nearby Melrose, where we gained admittance to the abbey located charmingly in a bend of the River Tweed.

I understand my brother almost as well as I know myself, so I did not doubt the genuine warmth of his greeting and pleasure in my company. This companionable situation endured for days until I encountered him alone when I asked about the Cuthbert Gospel. We brothers have never fostered secrets from the other, so his furtive reaction surprised and troubled me. At first, he denied that any such book had been found at the exhumation, but I knew by his eyes and secretive tone this was untrue.

“Don’t lie to me, Galan. I know you too well. What is to be gained by concealing our ancestor’s work from your brother?”

He flushed, a shifty expression on his face and his eyes darted along the silent cloister as if suspecting the presence of indiscreet ears,

“It’s nothing personal, Cynn, you know that. It’s just that the gospel is a treasure that must be kept safe at all costs.”

“So, you sealed it in the coffin with the relics?”

“Nay, that’s the problem, Abbot Eadred thought it wiser to preserve the book separate from the saint’s remains.”

“Where’s the sense in that? Lose the relics and all is lost.”

“That’s what I thought, but a mere scribe can’t argue with an abbot, Cynn.”

“Where is the Gospel, then.”

“The abbot chose me, I think, as a descendant of Aella, to keep it safe and he admonished me to let no-one touch it but myself.”

I stared hard at my younger sibling, “But I am your brother and also a descendant of Aella; I wish to admire the skill of the famed craftsman. What harm is there in that?”

His long, lean face, so different from mine, seemed to lengthen even more,

“You cannot ask me to break my oath, Cynn.”

That was true, a man’s vow is his bond, so on that occasion, I withdrew. But the desire to see and handle Cuthbert’s Gospel grew daily until it became a veritable obsession. A battle raged in my head between an ignoble urge to have my way, ranged against brotherly love and respect for Galan’s position. As though the Tempter was whispering in my ear, I justified my yearning by telling myself that Aella was my ancestor as much as Galan’s—more so—since I was the firstborn. Come what may, I grew determined to have my way.

TWO

ACROSS NORTHUMBRIA, SPRING 868 AD

The monks of Melrose Abbey were hospitable and our stay was comfortable both for men and horses but we anxiously awaited the arrival of spring to be able to move on. Our task, as outriders, was simply to follow the coffin bearers to ensure their safety in the remoter, more dangerous parts of the kingdom. As outlaws sought weak unarmed prey, six heavily armed warriors did not fall into that category and our progress was undisturbed by miscreants.

The weather was typically variable for the time of year and consequently the roads sometimes slippery with mud. Occasionally, the monks came close to falling and one day, one of them twisted his knee so badly that he could not continue. There were seven of them for this reason since six always shouldered the coffin and the seventh relieved the first among them to falter. At once, I offered,

“Let me take a turn, you can ride instead of worsening your leg.”

“I’m sorry, friend, only brothers accepted into the order are permitted to touch the sacred box.”

Despite my protests, they were inflexible and I suspected that they believed the more they suffered the better it was for their souls.

The days passed slowly, trudging from village to village and at every settlement the local priest, villagers, woodlanders, whoever beheld the coffin, fell to their knees before running off to fetch from their homes what meagre offerings they could barely spare. Often, our party would stop at religious houses where food, a bed and warmth for the night were assured. Slowly, we headed for the coast and I will list our route only for the record: we travelled from Melrose Abbey to Elsdon, Bellingham, Bewcastle, thence amid the rolling hills down to Hebdon Bridge, on to Beltingham until we came to the large settlement of Carlisle, where our monks once more met with Abbot Eadred. This affable churchman came up with the fateful suggestion that we should sail with the coffin to Ireland. His theory was that the King of Dublin, well known for being both of Viking stock and a devout Christian, would protect the precious relics from his original fellow-countrymen of the Great Horde, so busy at that time sacking Mercia. The argument was sound and convinced us all. I had a half-formed idea that I might be able to visit Ardfinnan where we had relatives on our great-great-great grandfather’s estates. With this plan in mind, we travelled on through Plumbland to Embleton and thence the last four leagues to the sea at the mouth of the River Derwent.

It was there that we found a vessel willing to take us via the Isle of Man to Ireland. As mentioned, the weather was variable and the sailors warned us that the crossing might be rough. The most senior of the monks, a prior, replied blithely that the saint would protect us. From the way the wind was freshening, I could only pray that he was right.

To my eternal shame, I have to relate a disgraceful incident that was wholly my fault. We boarded the ship in the estuary in relatively calm conditions and at that point confided to Galan my desire to travel down to Ardfinnan to see the place where Aella had found love and later settled to breed horses. The mention of Aella aroused my slumbering longing to see the Cuthbert Gospel.

“Brother, will you at least allow me a fleeting glimpse of Aella’s handiwork? I don’t ask to handle it, just a glance.”

Furtively, Galan looked around the deck and since the nearest monk was the prior, he drew me away towards the prow. At this point, the ship was nosing out into the open sea, where the water was rougher and the vessel began to pitch fearfully. My brother withdrew a pocket-sized book from within his tunic and I caught a glimpse of a marvellous red leather binding before I broke my word to try to snatch it from his grasp. At the same moment as he whipped his hand away from my lunge, the ship pitched and he lost his grip on the precious volume, sending it spinning through the air and down into the sea.

“No!” cried my brother, regaining his balance and clinging to the gunwales, staring hopelessly down at the murky, turbulent waves. “What have you done, Cynn? You promised; you gave your word. What can I tell the prior?”

I thought frantically, realising the seriousness of the situation,

“Tell him only this: the truth—that you were assuring the safety of the volume when the ship lurched, flung you off balance, sending the book overboard.”

“Ay, that is the truth,” he said ruefully, glaring at me, “but a cunning version, it does not include your fault, does it, brother?”

Since he’d accused me of cunning, I decided to be so.

“Regarding that, Galan, don’t you think it is between me and God? I shall confess my fault as soon as I find a priest to hear me. Meanwhile, I beg you to forgive me for my impetuous act, brother.”

If you’d let me see it in Melrose, young fool, the book wouldn’t be lost.

The sky darkened and the rain suddenly came in sharp spatters on the wings of a squall that flapped the sails frightfully. The sea rose high and flung foam, soaking us to the skin. The wind moaned through the rigging and the captain had had enough as the first silver flash lit the sky. Even as the thunder pealed, he steered the ship, causing it to roll alarmingly, so that we could fly back to the estuary.

As I clung to the mast in desperation, I saw, although over the howling wind could not hear, the agitated conversation between Galan and the prior. For a moment, I thought the senior monk would strike my brother, for he raised his fist, but he calmed and to my surprise, placed a comforting arm around him. I felt like a dog that had disobeyed its master and if I’d had a tail, it would have been firmly down between my legs.

Safely on solid ground, we begged admittance to the Derwentmouth monastery and spent the night there. In the dormer, I slept on a pallet next to my brother and found sleep elusive, likely because I blamed and tormented myself for the dropping of the irreplaceable Gospel. Thus, I watched Galan tossing and turning restlessly whilst asleep and his lips moving, forming sounds not recognisable as speech except for the occasional word. I ascribed his agitation to the same source as my sleeplessness. I knew the loss of Cuthbert’s gospel had affected him deeply and was grateful that his kindly nature and fraternal love were so ingrained that he could not hate me for what I’d done.

In the morning, the most remarkable happening occurred—Galan shook the prior awake and declared,

“Saint Cuthbert appeared to me in a dream this night, Brother Prior, he spoke to me telling me of a certain place where the Gospel is to be found on the shore. The obedient sea has returned it according to God’s will. We must leave at once, follow the coast to the north to seek the place the saint showed me.”

The prior, unlike me, was not sceptical but threw up his arms and praised the Lord. Once again, I did not cover myself in glory, saying,

“What nonsense! The sea does not obey the will of God!”

The prior stormed towards me with a raised fist, his face contorted in anger, but again he did not strike, for he was a better Christian than I and controlled his temper. Still, his tone was biting,

“How dare you question the will of the Almighty? Did He not command the Red Sea to open for the Israelites fleeing the Egyptians? And did Our Lord not still the tempest frightening the Apostles on the sea of Galilee?”

I admitted the truth of these events and begged forgiveness, setting off in a mood of crushed humility, praying that Galan’s dream would prove true. Riding along the beach, the invigorating air after the storm, the tangy smell of the strewn wrack and the clamour of the seabirds could not compensate for not finding the volume. But Galan continued insisting that the landscape was not that of his dream, so we went on slowly northwards, following the shore until towards evening before stopping for the night after a fruitless search. I confess I had no faith in this impossible venture. The next morning, the resolute monks continued their efforts until we came to a place called Kirklinton, and there, once more abandoned the task for the night. Next day, we reached the island of Whithorn. Excited, Galan recommended the brothers to keep a sharp eye, because the scenery resembled that of his dream.

Humbled, I may have been, but in my heart, I doubted the likelihood of ever finding the volume. Nonetheless, I could only admire the faith and resolve of the brothers, foremost among them, Galan. My feeble conviction told me that even if by some miracle the book were found, it would be ruined beyond recovery. Galan’s trust in Saint Cuthbert and the Lord proved me wrong because my brother cried,

“Over there! See the rock formation of my dream! The Gospel will be hereabouts!”

He relinquished his position as pall-bearer and began to run around along the shoreline like a demented terrier, and like that creature, sniffed out his quarry. With a roar of exultation, he pounced and raised aloft a red-covered book. The monks laid down Cuthbert’s coffin on the sand and knelt to give praise to God for this miracle. Tears ran down my cheeks, a sign of my gratitude and my heartstrings being touched by my brother’s joy.

Galan turned the pages and his face revealed the extent of the marvel: after three days in the sea, the book was wet but undamaged. Later, when it had dried completely, it was left with only a few lines of salt deposit on some pages. Purely thanks to this wonder, at last, I was allowed to touch, inspect and admire my forbear’s masterpiece. Galan told me that Aella had not written the text, which had been the work of the Lindisfarne scribes, men like himself, but that he had made the magnificent goatskin cover. Only later, had Aella learnt to read and write and produced the famous Vita Sancti Cuthberti. I could not help but think how fitting the tale of the re-finding of St John’s Gospel would have been for inclusion in that work. Impossible of course, since our adventure occurred five generations after Aella completed his masterpiece.

This prodigious event convinced me that Saint Cuthbert would look after his bearers whatever fate threw them and, for the present, the Danes were occupied elsewhere and posed no threat in this part of the land. I resolved, therefore, that our guardianship was pointless and that we six horsemen should return to Bamburgh to pursue our ordinary lives. The monks, for their part, chose to forsake the journey to Ireland in favour of continuing their wanderings around Northumbria. We left them at Carlisle to take the old Roman road towards Hexham.

THREE

NORTHUMBRIA, APRIL 868 AD

Our ride across the kingdom was uneventful until we came to a forested area where from out of the trees arose a pall of dense black smoke.

“A fire!” cried one of my companions pointlessly.

I slowed my horse, gathering the other five around me.

“I don’t like the look of this, let’s investigate, but keep your weapons at the ready and move with caution—keep close together!”

In this manner, we advanced down a wide trail, pocked sporadically where cartwheels had stuck in the previous winter mud, creating deep ruts. We came to a place where another track crossed ours and suddenly, along it came six horsemen—Vikings! Slung across the first horse was a blond-haired child, no more than four winters old, and his piping voice drifted to us over the sound of the hoofs,

“Help! Help, please help me!”

I decided on the spur of the moment,

“Take those five, I’ll deal with the boy!”

The five Vikings were hampered by driving plundered animals: two cows and three goats.

My rage was controlled, which made me a more dangerous adversary. How dare these raiders invade our land, burn our homes, steal our livestock and in all likelihood, make an orphan of this child and destine him to slavery? My horse was, in my opinion, the fastest in the kingdom and I drove him forward after the leading Dane, who had spurred his mount into a gallop. His comrades had halted to face my men, so I passed them in a blur of black, flattening myself close to the mane as a javelin flew harmlessly over my head. My quarry glanced back with a twisted grin on his large, flat face and kicked his steed to greater speed—to no avail as I gained on him. I could hear the child screaming in terror and this infuriated me the more. I reached down and carefully released my throwing axe, grasping it by the haft in my right hand. With cold calculation, relying on the sure-footedness of my mount, I took careful aim, waiting until we were only five horse-lengths behind, and hurled the weapon with all my might. True as a bee entering a bloom, the keen blade sliced through his leather jerkin planting between his shoulders and the tall rider crashed in agony to the ground. I wanted to finish him but had to stop the riderless beast thundering on along the trail with its vulnerable burden. Hoping desperately that the child would hang on, I galloped alongside, with my horse understanding the urgency of overhauling the creature ahead. I reached across, grabbed the reins and hauled the foaming-mouthed animal to a stop. At a glance, I understood that the boy was too young to ride a horse, so I took him in my arms and sat him in front of me, holding his trembling body tightly for a moment until he calmed.

“You’re safe now, little man. What name do you go by?”

He was too shocked to answer, so I did not press him. There were more urgent matters for me to deal with. I secured the raider’s horse, a fine bay and turned back along the trail. The Viking was on all fours, helpless, with my axe rising from his back like a perch fin. I drew my sword and gave him as little mercy as he had likely shown to the boy’s parents: in one scything blow, I removed his head. The most urgent matter now was to join my comrades to help them overcome the foragers. At a glance, it seemed my aid would not be needed, for three of the invaders lay dead on the ground, sadly, with my comrade, Ceadda. The remaining two Vikings, fighting for their lives and outnumbered were so strong that I feared for my companions. Hampered by the boy in front of me and fearing for his safety, I cried, “Cling to his mane!” having assured myself that he had obeyed, I leapt to the ground. Springing on to the captured bay, I entered the fray and, unexpected, my arrival turned the tide. In a matter of minutes, two more raiders lay lifeless on the blood-soaked earth.

“Who is… this fine fellow… on your horse?” jested my friend Eadwine, breathlessly.

“We have had no time for a chat,” I said, smiling grimly.

“Hildraed,” murmured the boy and began to sob, “t-they slew my father.” He pointed in the direction of the smoke.

“Stay with the boy,” I told Eadwine. That was an easy choice, as my comrade was ever the jester among us. The child had been shocked enough without returning to a scene of devastation. The four of us urged our horses forward and a mile down the track, in a cleared area of land beside a fast-flowing stream, the sight I had foreseen met our gaze. Three houses were now blackened, smouldering skeletons, their roofs collapsed and from the void, clouds of acrid smoke rose to be swept away in the breeze that came and went. The ravaged bodies of three men lay in the yard, their ineffectual weapons, a scythe, pitchfork and a half-decent spear, were scattered on the ground. I had just about decided that there was nothing to be done there, when my horse, a creature with a brain many a ceorl might envy, insisted on taking me to a still intact byre. Nosing inside, I heard a distinct groan and whimper. Somebody had survived! I dismounted and drew my seax, unnecessarily, for cringing, hidden behind a feeding trough I found a woman, her tear-stained face scratched and bleeding, hair unkempt and clothes ragged.

“Every one of the fiends is slain. You have nothing to fear,” I extended my hand but she cowered farther back, whining and snivelling. That is when I conquered her diffidence with an inspiration. “Hildraed is safe. Now come!”

“Hildraed!” she wailed and a fierce, wild look of hope and determination changed her aspect. I hauled her to her feet and let her cling to my arm until I hoisted her onto my steed and leapt up behind her.

A soul-wracking scream burst from her when she saw the mangled body of her husband and she sobbed all the way back to Eadwine where only the sight of her son made her cease.