3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

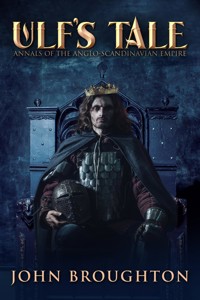

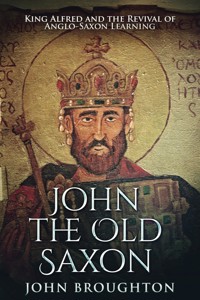

In his darkest hour, hiding in the depths of the Somerset marshes in 878 AD, King Alfred devises a scheme to save his kingdom from the Vikings threatening to overwhelm the country.

His spectacular success, beginning with the triumphant battle of Ethandun, involves creating a sense of nation among his subjects. To help with this, Alfred gathers a small band of brilliant foreign scholars in his court, chief among them John the Old Saxon.

Follow this epic tale set in medieval England and see how King Alfred laid the foundations for a united country, and the tenth-century Anglo-Saxon Renaissance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

JOHN THE OLD SAXON

KING ALFRED AND THE REVIVAL OF ANGLO-SAXON LEARNING

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Frontispiece

Foreword

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Appendix

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2021 by Next Chapter

Published 2021 by Next Chapter

Edited by Icarus O'Brien-Scheffer

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

Frontispiece: Interpretation of Brother Asher’s illustration of Psalm 20 by Dawn Burgoyne.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Arthur Broughton, (1898-1956) my grandfather, who instilled in me a love of history, but was lost to me far too soon.

FOREWORD

"There follow in order the Reudignians, and Aviones, and Angles and Varinians, and Eudoses, and Suardones, and Nuithones; all defended by rivers or forests. Nor in one of these nations does aught remarkable occur, only that they universally join in the worship of Herthum (Nerthus) that is to say, the Mother Earth." —Tacitus, ‘Germania’

PREFACE

Athelney Abbey, Wessex 904 AD

This tale is not about me, but about my beloved friend, flown to the bosom of our Saviour at a ripe old age earlier this year. My given name is Asher, like the eighth son of Jacob, but I am known here in my adopted land as Gwyn, meaning Blessed. I am a stranger from a land stranger still. Born in Old Saxony—I use the term to distinguish my homeland from that of Seaxna or New Saxony, whose people I frequent on these Britannic shores—I am the grandson of an illustrious grandfather, and must recount whence my friend John and I came.

Consider the shape of a triangle. Well, that was my homeland. From angle to angle a man would travel for eight days. The greatest of the tribal duchies, Old Saxony, embraced the whole territory between the lower Elbe and the Saale rivers almost as far as the wide Rhine. Between the mouths of the Elbe and the Weser, it bordered the North Sea. Ay, that devourer of ships, which our folk crossed at their peril many years ago to settle in the green and pleasant land where I now reside. I remain proud of my origins.

Our lands were a broad plain, save on the south, where they rose into hills and the low mountainous country of the Harz and Hesse. This low divide was all that separated our country of the Saxons from our ancient enemies and ultimate conquerors, the Franks.

That is why I admire my grandfather. His name was Widukind, which means child of the woods. His reluctance to accept the new Christian religion and propensity to mount destructive raids on our neighbours brought him into direct conflict with Charlemagne, the powerful king of the Franks and, later, emperor. After a bloody and attritional thirty-year campaign between 772–804, the Old Saxons led by my grandfather were eventually subdued by Charlemagne and even he was forced to convert to Christianity.

His life alone is worth a book and, maybe one day, I will use my scribing skills to revere him if my arthritic fingers, getting no younger, will permit. But first, they must toil over this vellum to honour the life of my old friend, John. His was one of the sharpest minds of his generation. Also, his learning surpassed that of any man I have ever known. Yet, in his youth, he was a fearsome warrior and it is in those years in Old Saxony that his tale must begin.

ONE

Athelney Abbey, 904 AD

I am an old man and can no longer hold the quill in my arthritic fingers. So, I have enlisted a young scribe, Brother Otmar, to set down my words. The youth has a keen mind and a steady hand. Also, he is of kindly disposition, only too eager to help this aged monk. All that is required is to rack my memory, for I will refer to a time more than a lifetime ago.

Gandersheim, Old Saxony, 830 AD

I will try to remember my first conversation with John word for word. We lay on an ice-cold flagged floor in a dungeon, close around our ankle an iron band chained to a ring in a damp stone wall, dripping rivulets of water. Defeated, captured, I was flogged and flung into the grim depths of a Frankish castle along with eight of my comrades.

“Don’t worry, we’ll soon be out of here,” were John’s first improbable words to me. I must have given him an evil glare because he hissed, “Suit yourself, but I’m telling you—”

“What?” I snarled, “that these chains will shed themselves and the guards will let us go, perhaps with a flask of wine in our hands?” He seemed impervious to the sarcasm and impatience of a twenty-year-old.

“I was saying, my family will have us released any day now.”

“Either that or they’ll bind us to a tree and riddle us with arrows.”

The truth is, I blamed him and his damned way with words for our plight. If he hadn’t stirred the sleeping wolf in our breasts, preying on our festering resentment of the Franks, we would have been out free to breathe fresh air, likely tilling our fields. The bonds of kindred and clan are strong among the Saxons, and notwithstanding our many divisions, he found a way to make us unite and revolt. We were of the same age. If I try hard, I can recall his words ringing in my ears on the fateful day I agreed to join him.

“Never forget the Blood Court of Verden, brothers, after Widukind defeated a Frankish army at the Battle of Suntel. What did Charlemagne do? You all know! He ordered the beheading of 4500 rebel Saxons on a single day. Let us fight to avenge them!”

Nobody cheered louder than I. He could not have known about the family connection but he had referred to my grandsire and a massacre that occurred forty-eight years before, during the Saxon Wars. The prisoner lying next to me was a Christian, but he artfully roused the wolf by reminding our folk of Charlemagne’s edict Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae which asserted, If any one of the race of the Saxons hereafter concealed among them shall have wished to hide himself unbaptized, and shall have scorned to come to baptism and shall have wished to remain a pagan, let him be punished by death. Lying on that pitiless, cold stone floor, lashing out with bare feet at intrepid rats approaching their unprotected toes, each one of our other companions secretly worshipped Woden.

John should have known that the Franks were better armed and organised than the ill-disciplined but courageous rebels he had mustered. His stirring speeches tugged at the hearts and minds of our oppressed folk. He spoke of a glorious opportunity because, not for the first time, our count, Wala, was aiding Lothair I, the eldest son of Louis the Pious, in rebellion against his father. In that May, 830, a short-lived uprising involving those of both clerical and lay orders as well as three elder sons of Louis, succeeded in forcing Empress Judith into monastic confinement. John declared this the perfect chance to overthrow the Franks. It might have been, had the rebellion lasted longer. As it was, the rebels managed to put pressure on Louis the Pious to abdicate. But their success was not enduring, for Wala finished in exile in a high mountainous region near Lake Geneva. With the undivided attention of the Franks in Saxony given to our uprising, our hopes were dashed on the battlefield.

I must admit that the tall, muscular figure lying beside me fought ferociously. I had wielded my axe close enough to him to admire the slaughter he effected. If all of our warriors had been so valiant, we would have carried the day. John only surrendered when the remnants of our force were surrounded by a ring of spearmen. Give him his due, he called out in a ringing voice to lay down our arms. Thanks to his discretion that day, I have reached this ripe old age.

Only in that dungeon did we get to talking where he confided that he was the black sheep of his family. The youngest of four children, his eldest brother was the same Wala who had rebelled against the emperor. His father Egbert was a count at the Frankish court, where John had grown up and studied before rebelling and running away, refusing to take monastic vows like his two brothers. His youthful dream, quashed in that dungeon, was to become a warrior and liberate Old Saxony. With hindsight, we were laughably idealistic hot-headed youths back then. And both were sons of a noble family. Perhaps that is why we became lifelong friends.

As I am a venerable monk, I should spare a word about John’s mother, Ida of Herzfeld. I would say that it was thanks to her influence that John grew into the man we came to respect and admire. She was the daughter of a count close to Charlemagne and received her education at his court. He gave her in marriage to a favourite lord, Egbert, and bestowed on her a great fortune in estates to recompense her father’s services. She was a saintly woman who devoted her life to the poor following the death of her husband in 811. But I am getting ahead of myself. I will return to Ida later in my narrative.

Two days after my first exchange with John, his words came true. Despite my scepticism, we were bundled outdoors and menaced in the courtyard.

“We’re going for a country stroll,” the officer jested, but there was no humour in his next words. “On our journey, if any man is stupid enough to run away, he will be caught. In that case”—there was an evil glint in his eye—“he’ll lose a foot. I’ll chop it off myself! Clear?” He bellowed, repeating the question and waving an axe. None of us doubted the sincerity of his threat.

They handed back our shoes. “You’ll be needing these,” and even this sounded ominous. Six and a half days of torture began as we jogged along on the trot whilst our captors, brandishing canes to discourage laggards, rode beside us. Only our thin linen protected us from those stinging wands. The weaker among us wore shirts dappled with bloodstains. “No cheese for malingerers!” the Frank bawled with gusto. That admonition kept us on our toes. We needed the hard, black rye bread and the rocklike goat’s cheese to replenish our dwindling energy, but it was water we craved most. Six leagues a day, due south, they required of us. Whence and to what fate was not revealed.

After six and a half days, we arrived at our destination, although we knew it not. I had admired the beauty of the woodlands fringing the broad swirling river, which later I learnt was the Fulda. The monastery, founded a little more than half a century before, lay before us.

“Your new home, brothers,” sneered the officer. “The Duke has given you a choice: either become monks or die. What is it to be? Those among you not wishing to wear the habit, step forward now!” Unsurprisingly, nobody moved a tired muscle to advance. “Right! Prepare to be tonsured.” They made us kneel, tugged at our hair and carved it away with their daggers. It hurt like hell and I’m convinced they relished nicking as many scalps as possible.

When his tormentor had finished, John, knelt next to me, muttered, “This is my father’s doing, I’ll wager. He always wanted me to be a monk, like my brothers.”

“Better a monk than a corpse,” I whispered back, running my hand over my sore head. The soldier had done a poor job with his knife. I felt the stubble against my palm. “Maybe the brothers will supply us with razors,” I said—correctly, as it turned out. We dragged our aching bones through the monastery gates and admired the stone buildings we grew to know and love. The abbey had everything necessary for monastic life. Looking back, the founder, Sturm, had chosen a magnificent remote location amid luxuriant surroundings. Yet, inside the walls nothing was lacking, the facilities included workshops for a variety of trades, stables, pigsties, pens, beehives, a smithy, furnaces, ovens and, of course, a chapel.

We were greeted by a prior, whose first action was to send for the infirmarian, which was the measure of this kindly monk. He had spied the blood-soaked linen on our backs and called for a soothing balm to treat the raw wheals. His second action was to enquire who among us could read and write. The only man to raise his hand stood next to me: my friend, John. The day had not passed before they put him to the test to demonstrate how learned and refined he was. It ensured his entry to the scriptorium, which proved to be a formative experience for him, whereas they consigned me to the chandler to learn the craft of candle-making.

The irony of our forced march of forty leagues, I discovered later, was that the place we had departed from, Gandersheim, was soon destined to have a monastery or, rather, a convent. On reflection, none of our motley crew would have graced a nunnery!

Within the first year, only one of our band left the monastery, for we were happy there. Fulda provided everything a man might need in exchange for service and dedication to prayer. I am pleased to think that we each grew into worthy brothers in Christ. Except, as I said, for one, a certain Gangolf who did not leave of his free will, but was banished for persistent petty thievery. He was likely destined to die in abject poverty in some squalid and ill-famed quarter. I know that Brother Irmgard had a secret hankering to worship Woden, but he wisely kept his sinful desires to himself. I caught him giving pieces of bread to a crow he frequented too often, but I never remarked on the sacred bird, contenting myself with a wry smile. However, I must not ramble and will, instead, relate something of John’s life at Fulda.

TWO

Monastery of Fulda, Saxony, 830 AD

On the day we tramped into the monastery, I noticed the large number of beehives set apart from the monastic buildings. A passing glance cannot reveal the industrious work of the bees and the beekeeper in the apiary. When assigned to the chandlery, for no evident reason except that I could not read or write proficiently, I had no knowledge or interest in the candle-making trade. Soon, I came to change my attitude. The candle-maker has a glorious but difficult occupation. Although my book is about John, it would be remiss of me not to detail how our divergent courses came to run together. The Fulda chandlery is as good a place as any to start that narrative.

My lot was to sweat over vats of molten wax, which was uncomfortable on hot summer days but blissful during the January snows. When I took in the aroma of beeswax, I breathed the flowers and grasses visited by the bees, the monks who tend the herb garden, the folk who hay the fields and the fruit growers who prune the orchards. We bring the land into our sanctuary in the form of altar candles. I still recall the joy of self-realisation at my first Easter in Fulda. We sang the Exultet at the Vigil when each person lit his taper, made by me, from the Paschal Candle, made by the chandler.

When I strolled over to chat with the brother beekeeper, I discovered to my surprise that he obtained two pounds of wax for each hundred pounds of honey. He explained this to me as he rinsed and drained the cappings in warm water. Satisfied, he threw them into a double-boiler to melt the wax; at last, I knew how he produced the forty-pound, square blocks that he brought me in his wheelbarrow. These, I liquefied in our fifty-gallon vat, and into the molten mass I repeatedly dipped my wick frame where the cotton wicking became coated by thin layer after layer of wax. After fourteen dippings, the tapers were thick enough and whilst still warm, I cut them out of the surround, trimmed the wicks, and chopped the ends square—all done! When not using a frame for important ceremonial candles, we had moulds where we carefully poured in the molten product. In a few special cases, the chandler transformed himself into an artist, shaping wax designs such as flowers or crosses, to colour the plain yellow-white candle shaft. Maybe watching this changed my direction, giving me a craving for creativity, reinforced also by our conversations about John’s work. These factors combined to lead me to join John in the scriptorium.

His enthusiastic accounts of new styles coming from Frankia aroused my curiosity, so I took every opportunity to wander into his haven of quills and coloured inks. One day, a striking picture of a kneeling stag in a landscape caught my eye; a red ribbon depicted with a bow tied at the top and bottom of the image. John’s deep voice came over my shoulder as I admired it.

“Beautiful, isn’t it? It’s an evangeliary from Tours in Frankia. Look, this is just one of the six full-page miniatures. All have ornamental decorations. See here…” He turned the pages. “And here. What do you think of the initials and borders? Aren’t they exquisite? Notice how they dyed the parchment purple before writing the gold and silver letters.”

“Superb! I wish I could learn to paint such designs.”

“Can you even draw?”

I smiled and did not reply. Instead, I bided my time until John was not in the scriptorium. Not wishing to take materials without permission, I spoke with the provisioner, who then indulged me with a few scraps of parchment and allowed me to use a quill and ink at a desk at the back of the room.

Just before I finished my sketch, his curiosity brought him to peer over my shoulder.

“By all the saints, Asher! That is an excellent effort!”

In truth, his words accompanied by laughter were different from those I report here, but bear with me, all will be revealed. That evening, after Compline, I sneaked into the dormer earlier than usual, pulled back John’s blanket, and slipped my artwork into his bed. Careful to smooth out the cover as well as my meticulous friend always did, I sat on the edge of mine and waited as the brothers arrived in ones and twos. To appear normal in every respect, I prepared for bed and was cosily under my blanket when John appeared. Unlacing his sandals and stripping to his undergarments, he pulled back the cover and picked up the parchment. Flushed and fighting back laughter he brandished it.

“Who is the scoundrel who did this?”

Curious monks gathered around, peering in the candlelight to grin and point, whispering snide comments.

“My nose is not that big and I do not have hair sprouting from my ears!”

“Oh, yes, you do,” I murmured.

He had not heard my remark, but his eyes were boring into mine. Possessed of acute intelligence, he said, “I know whose hand sketched this caricature! Yours, Brother Asher, for you are the only one still in bed—the only person not curious to see the drawing. And why is that? Because you knew very well what was on this vellum, did you not?”

Monks were grinning and winking at me.

“I cannot lie. It was I! I wished to prove to you that I can sketch as well as any man here by capturing your exact likeness.”

He did not rise to the bait but said, “I concede that you have a fine hand, Brother Asher, and everyone present must acknowledge how you captured my handsome features and extraordinary intelligence.”

Gales of laughter and ironic applause greeted this statement. One young monk had the temerity to say,

“In truth, Brother John, the sketch is decidedly more handsome than the real person.”

This met with gasps followed by much merriment. John glared at the audacious youth, who by no stretch of the imagination would have turned the head of Aphrodite or Persephone, remarked, “Hold your tongue, boy, or I’ll have the artist capture your donkey features.”

“Eeyore, eeyore!” several of the brothers brayed, taunting the embarrassed fellow. Everyone went to bed in high good humour.

As the acrid smoke of snuffed candles hung in the dormer air, John’s voice from the next bed whispered, “Well done, Asher, I will treasure this gift till the end of my days.”

My friends, he kept his word on that score. He also added, “Tomorrow, I will speak with the provisioner and seek to persuade him to let you join us in the scriptorium. Your drawing should convince him.”

“Oh, he’s already seen it,” I whispered back.

“Is there no limit to your knavery?” He pretended to be irate, but I knew him too well.

The next morning, the donkey-featured youth entered the chandlery,

“Brother Asher, the amarius wishes to see you.” I had just finished stringing the wicks, so I laid the surround aside for the moment. The wax could wait, simmering over the flames. The provisioner, his gaunt face lined with wrinkles under his fringe of grey hair, drew his spare frame close and smiled thinly.

“It seems that your friend over there”—he tilted his head towards John—“did not take your jest amiss. Indeed, he spoke to me of your earnest desire to try your hand at illustration.”

“Ay, Brother, I’d love that.”

The severe features of the amarius crinkled into an encouraging smile.

“I will speak with the chandler this afternoon. If he agrees to relinquish you, I will give you a week’s trial to gauge your suitability.”

Back to my boiler, the chandler drew me aside to remark on his satisfaction with my work, but give him his due, he grinned and quoted the Gospel of Matthew, “Jesus says: Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.”

I matched his grin and said, “I’ll wager all your quotes from the Bible mention candles!”

He laughed, clapped me on the back and added, “If you have a talent, you should use it to the glory of God, Asher. I can soon find a pair of willing hands to take your place. I hope the next one is as hard-working as you.”

So, we parted amicably, with me entering the scriptorium to John’s friendly smile and a nod of encouragement. The provisioner, Brother Adelbrand, for that was his name, allocated a desk to me, well-lit under a window, and gave me the benefit of his advice that lasted all morning. After lunch, he set me some exercises, copying scrolls and initials. It was enjoyable, but not creative. Satisfied, he placed a hand lightly on my shoulder and said, “Very good, Asher. Now I want you to lay out a full page illustrating the parable of the Sower.”

With hindsight, this was far too difficult a task to set a beginner to, but the provisioner must have seen something promising in my work. The centrepiece, the Sower himself, scattering seed, his head surrounded by a whirl of crows was coming along well until Brother Ganthar bumped into my elbow. Although he apologised profusely, I know that it was a deliberate act of sabotage. The jolt sent my quill scratching across the page but my wits came to my rescue. Converting the line into the ridge of a furrow, the illustration was not compromised.

Before Vespers, Ganthar returned to the scene of his misdemeanour,

“I hope I did not ruin your…” his voice trailed away as he gaped at my lovely interpretation of the parable. The borders with their miniatures and scrolls were not yet completed but the effect was captivating. I dislike false modesty as much as boastfulness—I speak plainly.

“Not at all, Brother Ganthar, your clumsiness helped me improve the design.”

His only reply was “Harumph!” and he walked away without a word of praise. That came instead when my day’s work was over in time for the evening service. The provisioner squeezed my arm and said, “Your week’s trial is over in only one day. Well done, Brother Asher! It is hard to believe that you have never illustrated before. You have a God-given talent. Isn’t that so, Brother John? I think that Brother Asher will help you with your evangeliary; since the parable of the Sower is often read during the liturgy, you can incorporate this wonderful illustration. Now, we must hurry to Vespers.”

On our way to the church, John said, “I’m delighted we can work together. You’ll do the illustrations and I will take care of the writing. We’ll talk in more detail after the service.”

“Good. There’s something else I need to ask you later.” I had Brother Ganthar on my mind.

After Vespers, we sat on a low wall enjoying the warm evening sun where I told him about the episode with the pinch-faced monk.

“You are right about him. I had occasion to complain to Brother Adelbrand after my best quill went missing. I accused no one, merely pointing out its disappearance, but the amarius told me to be wary of Brother Ganthar. He told me that the poor fellow had come to the monastery a wretched boy, as a refuge from violent, uncaring parents. The provisioner says he is damaged. He hinted that Ganthar might be a little unhinged. Undoubtedly, he has a spiteful side to his nature and often shows his jealousy, especially of friends—since he has none of his own.”

“We’ll have to be careful, then,” I said, nudging John. It was meant to be a light-hearted comment, but John grew silent, frowned and hummed, nodding with pursed lips.

Feeling that I should not leave the conversation dangling, I said, “I’ve noticed that he’s unpopular and the others shun him. Outside of the scriptorium, he latches onto anyone he can find and begins tedious speeches on any subject that comes to his mind. He always centres the discussion on himself: I is his most frequent word, interspersed with let me finish or you know what I think? He wants to be the centre of attention.”

“Don’t you feel sorry for him?” John asked, giving me a sidelong glance.

“Well, I suppose with such a troubled childhood, it’s understandable. But if he nudges my arm again, I won’t refrain from confronting him.”

“Since we are going to work together on the evangeliary, you can take the seat next to the wall and I’ll sit by the aisle. In that way, he won’t be able to brush against you. It’s a shame; he has excellent penmanship, you know.”

“His eyes are too close set for my liking.”

“My nose is too big for your liking!”

I was distracted talking about the spiteful monk, so he caught me unawares. I gazed at his face and said, “No, it isn’t. It’s normal: just right for your face.”

“Ha! I knew it—you have a cruel sense of humour, Asher. So, you see, nobody is perfect.”

He was referring to my caricature, of course, but he had made his point. I would have to cut Brother Ganthar some slack. I was not oblivious to the illustrator’s unsettling constant glances across the room as John and I discussed our work. My friend was writing the Beatitudes from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount in the minuscule script introduced by Charlemagne’s reforms. We agreed that these lines were not suited to illustration.

“Don’t worry. Next, I’m going to write the account in the Gospel of John, the one where Mary is weeping at Jesus’s empty tomb and sees the two angels. Surely, that lends itself to your colours.”