0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

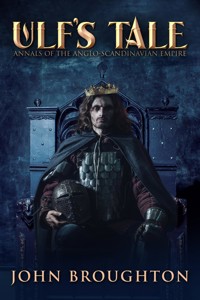

Aella is a leatherworker living in 7th century Northumbria. After surviving the war against the Picts, the king becomes his godfather, and Aella befriends Bishop Cuthbert.

Aware of Aella's skills, the monks of Lindisfarne commission him to make the cover of the Gospel of St. John as a gift for Cuthbert. Impressed by the masterpiece, Ecgfrith's successor, King Aldfrith, sends Aella to Ireland to learn to read and write.

Soon, Aella befriends a fellow student, learns to illuminate manuscripts, and falls in love. But can he achieve his dreams, and wed the love of his life?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

HEAVEN IN A WILD FLOWER — TALE OF AN ANGLO-SAXON LEATHER-WORKER ON LINDISFARNE

ST CUTHBERT TRILOGY, BOOK 1

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 by John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Apart from known historical figures, names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination. Other than actual events, locales, or persons, again the events are fictitious.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Heaven in a Wild Flower is dedicated to my charming wife, Maria Valente

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to my dear friend John Bentley for his steadfast and indefatigable support. His content checking and suggestions have made an invaluable contribution to

Heaven in a Wild Flower.

Frontispiece is by Dawn Burgoyne, with the text a fragment from Folio 1 of St Cuthbert’s Gospels (British Library). The illuminated capital is based on a border design from The Book of Durrow (Trinity College, Dublin)'.

Dawn Burgoyne, medieval re-enactor/presenter specialising in period scripts. Visit her on Facebook at dawnburgoynepresents.

ONE

HEXHAM, BERNICIA, APRIL 684 AD

What I ever wanted to do was follow in my father’s footsteps to be a leather-worker. In this, I largely succeeded except for a turbulent period that began in the workshop when a heavy hand laid on my shoulder made me start. I had just a score of winters behind me.

“Aella, son of Oswin?” a gruff voice said.

I put my knife on the bench and, although I am tall, looked up into the craggy features of a warrior a head taller than I.

“I am Aella, but who are you?”

“My name is Berhtred and I am here on King Ecgfrith’s business. You and your father are to come with me to war.

My heart leapt in my chest— unlike father, I had never been into battle.

“Where is Oswin?”

At last, he released the strong grip on my shoulder, at the same time pulling me round to face him. His broad chest, slim belted waist and muscled thighs told me he was as fit as a moorland stag; therefore, not a man to contradict. But that is what I had to do.

“Father cannot come, he lies abed with a sickness these five days. And if he is sick, who is to carry on the workshop if not I?”

He added a frown to his graven countenance and his hand went to the hilt of his seax.

“Would you defy your king, lad?”

I gulped, tried to force a smile and said,

“I will take you to father, Lord. You shall see for yourself how he fares and I obey his every word. Perhaps you will tell him of the king’s command?”

For one foolish moment, I thought of grabbing my knife, so close to hand, but the sheer size of the man and his undoubted prowess in a fight cooled my ardour.

“I will lead the way, Lord.”

The house needed a change of air because it was smoky and stuffy but my mother would not allow any draughts to worsen father’s fever.

“Mother, this is Lord Berhtred. He must speak with my sire.”

She looked anxiously at the towering figure, “But my husband is unwell, Lord.”

The warrior smiled grimly, “Fear not, mistress. I come on the king’s order and I will not overtax your man.”

I felt sure that he was checking on the honesty of my words, although what the haggard woman in front of him had just said should have been a confirmation. She pulled aside a heavy drape and indicated the space beyond that served as their bedroom. Father lay pale on his pallet, his brow glistening due to the fever. He groaned and tried to sit up but a huge hand pressed him down and considerately tugged the sheepskin back over his chest.

“I am sorry you are unwell, Master Oswin. King Ecgfrith sent me to gather men. We are away to war and the village headman gave me your name and that of Aella. It is clear to me that you are in no condition to rise from your sickbed, but your son is hale and will serve our purpose.”

I heard mother gasp and father’s eyes moved anxiously from our visitor to me. He looked aghast but could only groan.

“Are we to starve?” mother wailed, “Who will work the leather?”

The poor woman asked my earlier question. Without finished articles to barter for food, she would be in dire circumstances.

“If all goes well, Mistress, your son will be home before the autumn and his purse will bulge after his service.

This thought heartened me, but I had never fought in earnest and decided to use this as my final ploy.

“Lord, I am happy to do the king’s bidding but I am no warrior. I scarcely know how to wield an axe.”

A deep throaty laugh boomed in the confined space.

“There will be time for that, fine fellow. Come here, let me feel your muscles.”

He grabbed my arm and squeezed as I clenched my fist and raised it.

“You are no weakling, lad. We’ll soon have you ready. Master Oswin, I will send you a healer forthwith, but you are excused the summons. I bid you both farewell. You, Aella, come with me!

What choice did I have? Back in the village, I was delighted when he pressed Edwy the miller’s son into service. As children and youths, we had been inseparable. Work had caused us to drift apart except at feasts and ceremonies when we sought each other. Having an old friend on this venture, whatever it was, made a huge difference to my mood.

Berhtred was a man of his word: one of his few saving graces. He took us back to the chief, Hrodgar, and pressed silver coins into his hand.

“Find a healer for Master Oswin. When I come back to your village, I wish to see him on his feet and working his leather. Understand?”

His voice was generally gruff, but the last word was loaded with menace.

Hrodgar gazed from the money in his hand to the rugged face of the warrior.

“It is quite clear, Lord, I know just the woman. I’ll send a boy to fetch her forthwith.”

“Good, see you do! If Master Oswin is not cured, I’ll know who to blame.”

Our headman was formidable, used to bullying and getting his way, but he knew when to be subservient.

“The wise woman is skilled and will set Oswin to rights.”

I glared at Hrodgar, for he had given my name to the intimidating giant who was now steering us out of the hall.

“My thanks, for the healer, Lord,” I said.

He looked down at me,

“You will repay me with good and faithful service, Aella!”

In this matter, I had no choice.

The three of us set off along the trail that took us into the depths of the forest. Edwy and I knew the woodlands from boyhood and even now I came here in search of food. Young boars were my favourite prey but one had to be careful of the fury and vengeance of the adult beasts.

Little sunlight penetrated the canopy, despite it being springtime. The thicker summer foliage was more impenetrable but the April sky was grey today and the sun weak, so I couldn’t judge the time. I reckon we’d been marching for two hours and I began to feel weary when the clamour of voices drifted on the breeze.

“We are here,” was all Berhtred said.

‘Here’ turned out to be a large clearing by a stream. The tree-fringed dell was full of tents where men were sitting around fires, laughing and drinking. The nearest group fell silent when Berhtred drew near and looked anxiously up at him. He grasped one of them and hauled him to his feet,

“Shift your stumps, Sibbald. I want these men to be fitted out with weapons and armour.

“Ay, Lord.”

He rubbed his arm and I sympathised; my shoulder still ached from his earlier grip. The man led us to a billowing tent near the centre of the enclosure. Brushing aside the linen flap, he ducked inside and bade us follow. He opened a large chest and was pulling out leather breastplates. My expertise told me they were tough and made of ox hide. It was a relief that we wouldn’t be wearing mail shirts because these were much lighter and would protect from a seax blade if not a powerful spear thrust. Sibbald had a good eye or an experienced one because the sizes were perfect. Next, he passed greaves of the same material to shield our legs. Then, he said,

“Now young ‘un,” addressing me, “Will you take an axe or a sword?”

I had no hesitation. I’d never once wielded a sword, but used an axe to chop wood for the fire. This weapon was much heftier and I looked at it dubiously,

“Are there any axemen to teach me?”

He grinned,

“Don’t worry about that, Berhtred the Butcher will soon knock you into shape, my lad.”

I still wonder if it was that remark that made Edwy choose a sword. If so, he had chosen the harder school, as it later ensued.

“That’ll do for now,” Sibbald said, “the javelins and spears are still in untied bundles.”

“Where are we headed?” I asked.

“Nobody’s quite sure. Berhtred’s still picking up men or boys, like you two,” he sneered.

I promised myself I’d make him rue those words if I ever got the chance, but kept my own counsel for the moment. It was just as well because I soon grew to like him, beginning with his offer for us to join him by the fire to sup ale.

Over a drink, he confided in a low voice,

“Some say we’re heading overseas, but I can’t rightly say.”

“But where would that be? Frankia? Ériu?” I had heard them named but knew nought of their whereabouts.

He looked puzzled. I think we’ll be here for some days yet. The lads are guessing because someone heard Berhtred say we’re waiting for the good weather to come. That won’t be for at least a month. Berhtred will have you training in the mornings, like the rest of us, and resting up in the afternoons until we move out. You’ll be proper warriors by then. There’s sure to be other recruits coming from the lands around here. I’m surprised he only brought two from your village.”

“It’s a small place, four or five farmsteads, a mill—Eswy’s a miller—we have a smithy and I’m a leather-worker.”

“Are you now? That could be handy for repairs.”

“Except I didn’t bring as much as an awl,” I said regretfully.

“We’ve probably got the necessary tools in a chest somewhere, but take my advice, don’t mention your trade for the moment or you’ll have men on at you to mend their shoes, sheaths and goodness knows what else.” He laid a hand on my arm, “Concentrate on training. It could save your life and that of others, Aella.”

The other men around our fire were friendly too. I soon realised that camp life produced trust and friendship. There was lots of teasing, especially because neither Edwy nor I had beards like them. We both had moustaches after the manner of our village. I’d not asked myself why our menfolk chose to shave their chins, leaving only the upper lip whiskered. I told Edwy,

“The first thing I’m going to do is stop shaving. Anyway, there was no time to bring my razor. It’ll stop them having fun at my expense.”

“You’re right, I’ll do the same.”

In a matter of days, there was a noticeable shadow along the jaw. It didn’t stop the wags though, they simply teased us about the slowness of growth, which wasn’t true, but I was learning fast how to reply with witticisms of my own. Our banter earned Edwy and me many friends, also on the training ground, where the wooden mock weapons could still clout hard enough to make your senses reel. On the whole, I showed considerable skill with the axe and my nimbleness saved me many a violent knock. When I suffered a setback, I never bore a grudge and would always grin and joke with my assailant. Edwy followed my example but he had more difficulty with swordsmanship and ended up with many a painful bruise. I felt sorry for him but we were learning the hard way and I knew that one day this tough work would reap its reward.

I guessed that before April was out another thirty men had joined our ranks after us, taking the number of the warband to over a hundred. Sibbald confirmed this impression.

“One hundred and forty-eight to be exact. I know, because my task is to kit everyone out. There are only a few weapons and breastplates left. We began with one hundred and sixty-five of them…so you see.”

I overheard Berhtred ask how many remained and he said, “seventeen.”

This elicited a snort.

“I’ve about had enough of this rounding up recruits. Tomorrow, your group will come with me to Hexham. We’ll make up the numbers in town. Bring your weapons in case of trouble lads.”

This meant that Edwy and I, along with the other six, Sibbald included, would accompany our leader into the settlement. I knew it was the biggest in the area; I’d rarely left our village but my father had told me about it. He’d lived there with my grandsires when he was young. I was excited to leave the seclusion of the forest and felt proud to set off as a recognised warrior.

TWO

HEXHAM, BERNICIA, APRIL 684 AD

Uphill and down dale, we tramped and I could see why Berhtred had such muscular thighs—so his legs devoured the miles. Woe betide us if we slackened the pace, it meant a stinging cuff around the ear that set it ringing and smarting. Once was more than enough to keep a man on his toes. So, we arrived in Hexham in good time. The odours of human occupation were suffocated by a tannery on the outskirts of town. The others pulled faces and wrinkled their noses, but in my trade, I was used to the stench of those places.

“By Thunor, what is that foulness?” Edwy grimaced.

I laughed and showed off my knowledge,

“The hides have become pelts. Look they’re tipping them into vats of dog dung and chicken droppings.” I chose my words carefully, avoiding vulgarity, to lend them greater weight.

“Why would they do that?” my friend asked.

“To open the pores in the leather.”

“It stinks to the sky!” Sibbald grumbled.

“I’ll never wear leather again,” Edwy said.

“In the end, after steeping and oiling, it comes out clean enough.”

“What do they oil it with, Aella?”

I frowned, it depended on supply,

“Well, either with fish oil or animals’ brains. It softens the leather and makes it supple.”

“In the name of Woden,” Sibbald said, “who in his right mind would be a tanner by trade?”

I laughed, and nudged him, “No tanners, and there’d be no leather; no leather, and there’re no boots, clothing, shields, and armour, tents, bottles and buckets, just to name a few things.”

“I suppose you’re right. But the townsfolk did right to set them beyond the houses and downwind at that.”

“You can’t gainsay that!” Edwy chirruped.

Chuckling, we marched on into the town, where the smells were still close to overpowering as the filth had accumulated in the streets along with scavenging crows, kites and rats flapping or scurrying in a constant whirl of movement.

Ten summers past, monks had founded an abbey near the marketplace and we caught sight of an agitated group of brown-clothed brethren around a cart with a broken wheel. The burden was well covered, but the load must have been heavy and the solid wheel had ceded at its joints.

I am practical and, feeling I could help, called a halt.

“Lord Berhtred, let us aid these poor fellows!”

“Ay, help them,” he said gruffly.

I gave orders and our lads hoisted the cart so that the wheel no longer touched the road surface. I picked up a rock and knocked out the oak peg passing through the axle.

Berhtred who had been looking on, leapt forward to lend a hand to lay the wheel on the ground. Without hammer and nails, nothing could be done to repair it.

“Hammer and nails!” I cried.

The fellows holding up the cart were beginning to suffer and two of the monks joined to help keep it suspended. Two minutes later, a wiry man with filthy long hair came running, a hammer in his hand. He pulled nails out of his tunic and handed them to me, too breathless to speak. A few well-placed nails strengthened the broken joints and in moments, Berhtred and I had the wheel back on its axle. I whacked the oak peg back into place and straightened up with a smile, calling,

“Set it down, lads, gently does it!”

With a groan, the cart settled under its load.

“It’ll see you home, brothers, until you can get a wheelwright to change it.”

“We have no money for your services, friend.”

“And I would take none,” I smiled.

He untied a string from around his waist, bearing a wooden cross.

“Then, take this. Our God will keep you safe.”

I tried to protest that I wasn’t a Christian, but he silenced me.

“Keep it with you at all times and God will protect you.”

I didn’t know about that, but I did know about amulets and their magical power. This was surely, the same thing, so I stifled my protests, turning them into thanks and wore my new charm proudly over my tunic. I watched their ox heave away the creaking cart with satisfaction and a hefty clap on the back set me arching again.

“Well done, Aella, you’re a useful fellow to have around!”

I think that was the only praise I’d had so far from grumpy Berhtred, so it meant a lot to me. But that was nothing compared with what was to come inside the blade grinder’s workshop. There, Berhtred spotted a likely-looking youth and signalled Edwy to seize him. This he did, but at the same time, the grinder straightened from over his work and began to shout and curse.

“You leave him be, you devil’s spawn! Do you hear? That’s my boy you’ve got there!”

“Hark!” cried Berhtred, “King’s orders, he’s to come to war and you’ll obey your ruler!”

The man shook his fist and a vein stood out on his neck,

“The boy’s only ten and five winters—unhand him, I say!”

Except me, everyone was staring at the grinder’s antics. I’d noticed a greybeard in the darkened corner of the workshop behind a bench littered with tools and weapons. At least three-score summers to his wiry frame, the old man seized a knife and hurled it straight for Berhtred.

“Look out!” I yelled and raised my shield to protect our leader. With a thud, the knife embedded in the stout linden wood. I did not doubt that it would have found its target without my timely intervention. Berhtred grasped the hilt of the knife and with his massive strength freed it from deep in the shield. He examined the skilfully balanced blade, designed to fly with accuracy.

“Mmm, a handy weapon,” he feigned concentration on the knife, but in one cat-like movement before any of us realised, it was slicing through the air back whence it came. Another thud, and the blade buried to the hilt in the old man’s chest. His eyes widened, his mouth gurgled and a crimson flow issued from his lips as he sank to the floor.

“You’ve killed my grandsire!” The youth howled and struggled in Eswy’s arms. A ferocious blow to the ear from Berhtred stilled him and he wailed in pain and despair.

“You!” Berhtred pointed at the grinder. “I have changed my mind. You’ll come with us too and this brat will be your responsibility. One false move and I’ll slay him rather than look at him, understood?”

The man nodded mutely and came to embrace his weeping son. I stepped over to the dead man and pulling the knife from his chest, wiped it on his tunic and stuck it in my belt. It was too valuable a weapon to waste. Besides, I felt that I’d earned this prize. I would practise and become as proficient as Berhtred.

Berhtred, who was now beaming at me.

“Aella, I have you to thank for two reasons: first, you saved my skin; second, you taught these ragamuffins here a lesson in how we cover each other’s backs. Got that, you wastrels? If it hadn’t been for Aella’s alertness, it would’ve been me stretched out on yon floor!”

I felt ten feet tall and like a fully-fledged warrior—even if that was overdoing it a little. But I had initiated my shield and that was more than Edwy could boast.

We scoured the town, for Berhtred was determined to procure stronger bodies for our warband than the grinder and his son provided. He made no move until he found a giant as tall as himself. He pointed him out and said, “Aella, fetch him to me!”

My heart sank. This brute was twice my size but I refused to let my comrades sense my fear for all that my knees had turned to gelatine. I strode up to him, tapped his chest with a finger and looked him in the eye. That was even worse for me, his furious grey eyes turned to flint and his broad flat-nosed face came close to mine.

“What!” he bellowed, no more than an inch from my nose.

Luckily, my companions could see me but couldn’t hear my squeaky voice, feeble with terror.

“You’d better come with me, friend,” I croaked, “see that giant over there? Well, he wants you and if you don’t come, he’ll strike your head off.”

Was that consternation on his face? I dearly hoped so. I watched the grey eyes swivel and fix Berhtred. He stared for a long moment, then turned back to me.

“Plucky little fellow, aren’t you?” He growled, slapped me on the back, something like a buffet from Berhtred, “Let’s go see what he wants, then.”

He linked arm under mine, just like a close companion, my feet hardly touching the ground, and we made straight for our leader.

“I brought him, Lord,” I said, against all evidence to the contrary—if anyone had done the bringing, it was the giant.

They were all impressed, nonetheless, and it turned out that the man had been a former warrior in the Mercian War and was glad of a chance to fight again. Berhtred was delighted to have netted himself such a specimen.

“In the shield-wall, he’ll be worth any two of you!” he trumpeted, but he beamed at me as he said it.

By mid-afternoon, we had brought our numbers to completion so that a group of two-dozen men left Hexham on the trail back to the forest. Our task had been made easier by the inclusion of three very strong men, who, once enrolled, took upon themselves the mantle of enforcers and guardians so that no thought of fleeing ever entered the head of any recruit. In any case, refusal to do the king’s bidding was tantamount to treason and would have led to death or outlawry.

Among the foot-weary, I returned to camp with my heart singing. I had acquitted myself well and Berhtred, our leader, made his approval clear. Maybe, I thought, life away from the village wasn’t so bad, after all. With our number complete, there would be no further forays other than to replenish the food store, rapidly diminishing with one hundred and sixty stomachs to satisfy.

Our mornings were filled with arms training—often we were lined up in two opposing shield-walls to experience the expenditure of strength required to hold the might of the enemy at bay. A few weeks of this, and I noticed that not just my arm muscles were bulging, but also those of Edwy. In this, he had a head start over me, from his years of humping sacks of grain and flour.

I chose to spend my afternoons some distance from my comrades where I could practise throwing my deadly knife. I used a kerchief snagged on a tree as a target and after a few sessions, I was able to rip it in half to make a smaller target. I numbered so many hits that the cloth was shredded and not much use so that I had to beg a rag from one of our comrades. This I cut into small squares and became so skilful at throwing the knife that I took it as an affront if I missed—this happened rarely, and only if I’d driven myself too hard.

Imagine my dismay when I realised I was being spied upon. At first, I wasn’t sure, noting branches twitching, which might simply, in my mind, have been caused by a large bird. But one day, when I heard a cough suppressed and spotted a flash of yellow cloth as I approached, followed by a footfall running away, and I knew it wasn’t my imagination.

A few days later, I noticed a fellow from another group casting envious glances at my knife thrust into my belt and he was wearing a dirty yellow tunic. I decided that I’d keep a wary eye on him, but he was too crafty. He sneaked up at night and coolly slid the knife from under my belt. I found it missing in the morning, which is when I sought him out to accuse him of the theft. Of course, he feigned outrage and made a scene, which ended in us pushing and shoving each other before fists flew. Then, my comrades came a-running to my aid, shouting,

“What’s going on?”

“This fellow’s stolen my throwing knife.”

“Liar! Prove it!”

This is where I was grateful to Sibbald,

“Oh, we will right enough!” he said, tipping out the man’s pack on the ground. Of course, too obvious, it wasn’t there among his belongings. But Sibbald, astute as a stoat in winter, tossed the man’s pallet of ferns, and blankets aside and studied the soil under it.

I knew at once and so did Sibbald, who leant over the spot where the earth had been freshly disturbed and dug into the soft ground with the point of his seax. In moments, he was brandishing my knife for all to see.

“I don’t know how that got there!” the wretch said lamely and even his companions, who were spoiling for a fight with mine, sneered and hissed ‘nithing’.

Sibbald marched him at seax point, with many a threat, to Berhtred to accuse him of theft.

Since this was a grave matter, I was pleased that the case was irrefutable. Also, I was Berhtred’s favourite at the time. Our leader listened to the accusation and looked as if he would strangle the thief with his bare hands. When the thunder had cleared from his face, he said, “Ina,” for that was his name, “there are witnesses to your theft and you know the penalty. I will have no thieving in this camp. You will forfeit ten silver pennies to be paid to Aella before the setting of the sun. You will both come here to me when the sun touches the top of yon tallest tree.”

Ina blanched because ten silver pennies was a fair sum in that, the fourteenth, year of King Ecgfrith’s reign. I did not doubt that the miserable thief had spent all afternoon begging around the camp for silver coins. When he came with leaden steps to join me before Berhtred’s tent as the sun sank to the treetops, he glared at me as though I had injured him, not the other way around.

“Have you brought the ten pieces of silver, Ina?” Berhtred boomed.

The wretch trembled, and began to snivel,

“Nay, Lord, I could not raise the sum. I made a terrible mistake. I beg Aella to forgive me. It was a moment of weakness.”

“That it was not!” I glowered at him, “I know you planned to steal my knife for many days and you sneaked up in the night when everyone was asleep to spirit it away. Not satisfied, you buried in the ground where you thought nobody would find it. What do you say to that?”

“It’s true and I wronged you, but now I’m pleading with you.”

“Silence!” Berhtred bellowed and glared around the small crowd that was forming to see justice dispensed. “The law is clear on this,” he continued, “if the stipulated sum is not paid in the stated time, the thief must lose a hand.”

Ina cringed and whimpered, “Lord, I beg of you…Aella…have mercy!”

I decided at that moment that I would pity him, only not as he meant it.

Berhtred grasped Ina by the arm. Even the strongest man in the camp couldn’t have broken that grip. There was no chance of flight.

Aella, find a decent log and bring your axe. The hand is yours to take!”

I hurried away and found a sturdy fallen branch, a yard long. Next, I fetched my axe.

“A good clean blow,” Edwy advised, “Don’t hesitate.”

He walked beside me back to Berhtred, breathing words of encouragement and condemnation of Ina. It strengthened my resolve as I tossed the log on the ground at their feet.

“No!” shrieked the wretch, his eyes wild.

“You asked for mercy, and I will give it to you.”

“What!” exclaimed Berhtred, his face a mask of fury.

I smiled at him and said,

“Ina, are you keck-handed or do you use your right?”

“My right!” he screamed.

“Then I will take the left and count yourself lucky!”

At this, Berhtred roared with mirth and pinned the left arm of the villain to the ground at the elbow.

“Lower your wrist to the log or it’ll go far worse for you,” I cried.

As if in a bad dream, I raised the axe and brought it down with all my new-found strength. When I stepped back, I looked in horror, as if I hadn’t delivered the blow, at the gushing blood and the hand with its curled fingers severed on the ground.

I always kept my blade whetted and fit to shave with, so the strike had been clean.

“Quick!” shouted Berhtred, “Fetch a brand to seal the wound!”