0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

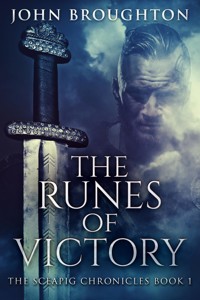

In 798 AD, the peaceful life of deer herder Deormund is overturned when Vikings arrive to raid the isle of Sceapig. Pursued by the marauders, he kills their chieftain and takes his sword as a trophy, unaware that there is more to the weapon than meets the eye.

Compelled by a neighbouring thegn to join his bodyguards, Deormund's prowess increases the leader's respect for him. But after the Vikings attack again, this time on Lyminge Abbey, he is forced to reassess his attitude to life.

Tasked by the Archdeacon of Canterbury to defend the island, Deormund prepares to face a fearsome foe. But what power do the inscriptions on the blade have, and why are the Vikings so driven to reclaim it?

Set in late 8th century England, The Runes Of Victory is a riveting historical adventure that captures the spirit of the chaotic medieval times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE RUNES OF VICTORY

THE SCEAPIG CHRONICLES BOOK 1

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Explanatory Notes

1. Sceapig (Isle of Sheppey)

2. North Kent coastal area

3. Sceapig (Isle of Sheppey)

4. Sceapig

5. Sceapig (Isle of Sheppey)

6. Faversham, Kent

7. Canterbury

8. Faversham

9. Faversham, Kent

10. Faversham, Kent November

11. Oare, Kent

12. Lyminge, Kent

13. Faversham, Kent

14. Faversham, Kent

15. Sceapig, Kent

16. Sceapig

17. Sceapig

18. Sceapig

19. Sceapig

20. Sceapig

21. Sceapig

22. Sceapig

23. Sceapig

Appendix

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2021 John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Lorna Read

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

An extract from a letter written by the scholar Alcuin from the court of Charlemagne, addressed to the clergy and nobles of Kent in 797 AD (See Appendix for translation) Frontispiece by calligrapher Dawn Burgoyne

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I should like to acknowledge the encouragement and suggestions of my writer friend Randal Solomon (St Louis, Missouri) whose contribution has helped to make The Runes of Victory better.

Special thanks go to my dear friend and fellow writer, John Bentley, for his steadfast and indefatigable support. His content checking and suggestions have made an invaluable contribution to The Runes of Victory

SCEAPIG (ISLE OF SHEPPEY)

798 AD

Deormund turned the whittled object in his hand, not yet satisfied. Another trimming of the fipple, the mouthpiece of the horn whistle, a rigorous scraping of the flue and it was ready. The twenty-two-year-old never wasted a shed antler, carving them being an integral part of his life as a deer herder. The haft of the knife he’d just sheathed was his handiwork. He wondered how his best friend would respond to his latest piece of handcraft. Only one way to find out—he raised the whistle to his lips, blew, and it emitted a shrill note that carried on the sea breeze to the woodland where Mistig was passing the time.

He came, breaking out of the trees, bounding towards him, lolloping to a halt, his shaggy grey head tilted inquisitively as if to ask what adventure awaited. The deerhound’s chest heaved, his tongue lolling after the exertion of his sprint to his master.

“It looks like the whistle will do, Mistig, if it brings you like that. You were so fast I should have named you Windig. But your name better suits your shaggy grey coat.”

The hound wagged his tail, which was long enough to touch the ground, the eager-to-please companion responding to the tone of his master’s cheerful voice. Mistig was one of the main aspects of Deormund’s life that made it so perfect.

He was the first and only deer herder on Sceapig—Sheep’s Isle—all the other inhabitants being shepherds who bred, bought and sold ewes and mutton. The island was separated from the mainland of Kent by the Swale Channel, where ships sometimes sheltered from the fury of the open sea. This strait provided a natural barrier to predators, making life easier for those who tended their flocks or, in the unique case of Deormund, herd. His eye strayed to the southern side of the isle as he distractedly stroked the beard of his hound. That part of the island was marshy, crisscrossed by drains and inlets where the sun flashed off the sparkling water on this fine late-spring day. The silvery flashes, offsetting the white of the frolicking lambs and sedate ewes interspersed with the chestnut coats of his hinds, made him sigh. Was there a more perfect life? If there were, it probably pertained to a nobleman, he thought wistfully. Ay, those wealthy thegns who relied on him for their hunting ritual, not to mention, by association, the venison for their table.

“I’m glad I didn’t follow in my father’s footsteps to become a shepherd, Mistig. If I had, I’d never have brought you to Sceapig, would I?”

By way of reply, the seemingly fearsome, but docile, animal snuggled his flat head into his master’s chest. He could do this because the deer herder was sitting on a smooth boulder, his favourite perch, likely deposited from the seabed by a storm. Folk could not imagine the appalling force of an enraged sea. The two remained locked in this amiable posture for some time, Deormund happy to reflect about his life on such a peaceful day and setting.

He sometimes wondered whether the choice of his trade had been determined unwittingly by his parents soon after his birth. When baptised a Christian, like them, in the church of the metal-workers’ village across the channel, the priest of Faversham had asked, “What shall he go by?” and his father had replied “Deormund.” It was not a common or even family name but, in accord with his parents, he liked it. Mund means protection and the deor is a beautiful animal, especially the male—Deormund identified with the stag, while his lean, muscular frame and chestnut-coloured hair and beard set many a hind’s heart a-flutter on market days in Faversham! Not that Deormund had time for womankind, because his work as a deer protector absorbed him and rarely left him with idle time, such as these beatific moments of reflection. Besides, he considered himself too young to wed, which was nonsense, as his mother continually stated when nagging him to find a bride.

Was that his father down by the creek? He smiled fondly; it seemed to him that his father cared more for the ewes than the youngest of his three sons. At least he didn’t badger Deormund about finding a maiden. He understood and approved of his son’s dedication to his herd. But mostly, he appreciated the steady flow of coins that entered the family home, for Deormund unstintingly shared his hard-earned income with his parents. His elder brothers had chosen to gain a living in Kent. They kept a tight knot on their purse strings. In any case, Cynebald was a family man: his priorities lay justly with his wife and two girls. Cynebald’s skill as a smith and reputation as a good husband and father was well-founded—he chuckled at his unintentional pun, causing Mistig’s tail to wag again—“Well-founded, are you with me, boy? Founded, foundry, see?” He laughed heartily and the hound leapt away from his embrace and began to bound around, as much as to say, haven’t we work to do?

They had, but Deormund was waiting for the wind. He needed to capture a new stag, preferably four years old or more. It was the right time of year for trapping because the fierce stags shed their antlers this season, so capturing one would be less dangerous. The old boy that serviced the hinds was long in the tooth. Time for fresh blood. The wind was a problem; he had waited three whole days for it to strengthen. A stiff wind brought the deer out from the undergrowth to cruise along the downwind cover in untroubled search for feeding opportunities.

“You’re right, my lad.” Deormund addressed the hound, whose short ears were pricked to catch the nuances of his master’s tone. Was this an allusion to work? There was nothing Mistig would prefer at that moment than a headlong chase after a stag. “We should take the ferry.” The dog barked and wagged his tail in approval: he knew the word ferry meant work and exercise.

Deormund hurried home to collect his hunting bag and money pouch. The former contained a net to snare his prey, as well as twine and a rope for a leash. As soon as his mother, Bebbe, saw him swing the pack over his shoulder, she asked, “Are you off to Harty Ferry?”

Deormund sighed heavily, knowing that admission would lead to the usual request. “Ay, I’m away before the wind gets up.”

Sure enough, the little woman, who was only tall enough to reach his breastbone, clutched his arm. “Wait, while I ready a package for our Eored.”

She fussed around, wrapping cured sausages into linen cloth. She grasped a string net containing winter apples. “Here, put these in your bag. Eored should be fattened up; he was all skin and bones last time he came over. I don’t know what you two have in your heads—un-carded wool, like as not! A man needs a good woman to look after him. Take our Cynebald, for example, he has two beautiful daughters!”

“Ay, that’s all I need, another three women to nag me!”

He snatched up the proffered packages, stuffed them into his backpack and grinned provocatively at the tiny, loving woman, another lynchpin in his perfect life. Why should he swap her expert care and attention for a younger, inexpert version?

“I was going to stay with Cynebald, Wilgiva and the girls, but a visit to Oare will do just as well, I expect our wheelwright will be pleased to see his brother.”

“Of course he will! Besides, Oare is only across the creek from Faversham; you can call in on your nieces easily enough.”

She smiled fondly at her tousle-haired son, thinking proudly what a handsome catch he would make for some young woman. The object of maternal machination dodged through the door, accompanied by his impatient hound, overjoyed at the sight of his master’s pack, a guarantee of adventure. As he hurried away, his mother’s call to find himself a maid in Faversham was lost to his distant hearing.

The boatman, seated at the door of his hut, greeted them with a cheery wave as soon as they came in sight. Deormund and his hound were regular and valued customers, crossing the channel at least twice a month. Helmdag, the ferryman, liked the young deer herder who neither haggled nor failed to pay the fare, unlike many others. The boatman charged his passengers according to the weather conditions. Sometimes crossing the Swale set his toned muscles afire, other times the boat seemed to shoot across the three-hundred-yard stretch of water.

“You know a thing or two, lad!” The old ferryman tapped the side of his hooked nose. “Favourable current, backwind and no ebb plume from Conver Creek. I’ll have you over there in a heartbeat!”

Deormund grinned, knowing it meant the fare would be lighter on his purse. The hound, used to ferry travel, was already sitting beside the rowing boat, his tail thumping the ground.

“Can you take me right into Oare Creek, Helmdag? I’m going to call in on our Eored.”

“Right you are.” the ferryman’s strong pulls had sped them beyond midstream. “Is the young fellow still unwed?”

Deormund groaned inwardly. What was it with the people of Harty Island? Why could they not leave him and his brother happily unbetrothed?

“I hope so,” he said, after a brooding silence designed to dissuade the boatman from further questioning. He had little success.

“You know how people will chatter?” the ferryman continued. Deormund nodded, he did know only too well. “I heard he’s walking out with the miller’s daughter. So, it’ll be your turn next, young fellow-me-lad!”

With a stern expression, Deormund muttered an oath that was lost in the wind, which only served to earn him a broad grin. Much more of this and he’d threaten to become a hermit. Slipping a coin into the boatman’s hand, he made his pleasant farewell, watching Helmdag pull strongly away from the wooden platform into the midstream of the creek. Mistig, already sniffing around this less usual landing place, re-established familiarity with a clump of heather.

“C’mon, Mistig, we’re bound to catch Eored unawares!”

At the name ‘Eored’, the hound yapped and pranced around his master’s feet, almost tripping him and eliciting a very unhuman growl that served to calm his exuberance.

Head bowed over his work, which consisted in repositioning a reinforcing panel on a cartwheel before nailing it into place, Eored saw only his brother’s feet.

Without raising his head, he said, “Good afternoon, Deormund. What brings you to Oare?”

“Have you grown eyes under your hair? How did you know it was me?”

Eored straightened. “By your shoes—few people around here have footwear made of deer hide. Besides, I could see Mistig’s huge grey paws next to you.”

At the mention of his name, the hound began the ritual festivities, tail wagging, bounding around one of his favourite humans. As expected of him, at least by the dog, Eored ruffled his fur until the animal rolled onto his back to expose his stomach for stroking. Eored, who loved Mistig as if he was his own, obliged.

“So, what brings you to Oare?” he repeated.

“It appears that my mission is to fatten you up and check that you’re betrothed.”

The wheelwright tipped back his head, unwise in his squatting position over the hound, wobbled, and stood. “How is our mother?”

They chatted over such pleasantries until Eored suggested an ale in the nearby tavern. It proved to be a drink that would unexpectedly change the perspective of their sedate lives.

At the next table sat a man with a black eye and dried blood in his blond beard.

“Looks like he’s been in a fight,” opined Deormund idly.

“Frodwin? That’s odd. He’s a peaceable fellow, a sailor, he works out of Faversham for a trader in sheepskins and wine. They take the wool to Frankia and bring back wine. Let’s cheer him by offering an ale. He must have a tale to explain the mystery.”

A few casual remarks and they were soon engaged in conversation with the eager recipient of the ale.

“What happened to your face, friend?” Deormund asked.

As suddenly as a windswept cloud passes in front of the sun, the trader’s countenance darkened.

“I’m in trouble now. Have to find another captain. I’ll wager someone will want a man of my experience. He’s dead, see?”

The brothers rightly assumed he was talking about his former employer. This, he confirmed. “They drowned poor Oswin in a barrel of red wine. Held his head under till his soul fled. That’s how I got this swollen eye, trying to save him. I also got a lump on the back of my head that left me senseless. When I came to, there was no sign of our captain. They must have thrown him overboard. At least, they were carousing and half-drunk on the wine, likely their drunkenness helped me. They used my mates and me to roll the wine barrels over to the side and hoist them into their vessel. A beauty of a ship, theirs, long and narrow; I’d reckon twenty oars each side.”

“Pirates then, but who were they?” Deormund asked exasperated.

Frodwin touched his bruised cheekbone gently but still winced: a gesture that the brothers separately thought reminded the sailor of his misadventure.

“They call themselves vikingar, which means sea-rovers in their language—another word for what you said, pirates!”

“Do you know whence they hail?” Eored asked.

“Where are they from? In my experience as a trader, I’d say they are from the far north, at the edge of the world. Take my advice, if you come across a vikingr, give him a wide berth. Those fiends are merciless—take what they did to Oswin because he tried to defend his goods.”

“Yet, you live to tell the tale, friend.”

The trader gave Deormund a sour look. “Ay, only thanks to the cask lid they’d prised off and flung into the sea. When we finished shifting the barrels, they had no further use for us and hurled all five into the sea. None of my mates can swim and they all drowned.” His voice caught, causing him to pause to suppress his emotions.

The brothers waited respectfully as he took a long swig of ale. Setting down his beaker, he resumed his tale. “As I said, I was lucky. You can’t stay afloat for long in these clothes, but I managed to reach the lid and cling on. I wager they were too drunk to notice, which accounts for why no arrow or spear struck. Saved by an act of scorn, for contempt was what it was when the vikingr flung the wooden cover into the sea. It buoyed me long enough for the current to bring me ashore. I reckon they must have boarded us a mile or so out of Herne Bay, where I washed up.”

“In your misfortune, you were lucky, Frodwin. Another ale?”

“Ay, don’t mind if I do. But mark my words,” he stared hard with his unsettling injured eye, “if ever you come across the vikingar, expect no mercy.”

That observation would return to haunt the brothers and shake them out of their perfect lives, miller’s daughter and all.

NORTH KENT COASTAL AREA

798 AD

Saewynn, the miller’s daughter, whose pretty face, characterised by a liberally freckled turned-up nose and framed by flame-coloured hair, instantly endeared herself to Deormund. Following the rule, love me, love my hound, the deer herder beamed at the slim maiden who, upon encountering them as they left the tavern, ignored the two men in favour of Mistig by squatting and flinging her arms around the shaggy beast’s neck, squeezing him to her breast.

Releasing her over-willing captive and looking up, she addressed Deormund. “What a lovely hound! What’s its name?”

“I’m Deormund,” he grinned, “and yon’s Mistig.”

The girl, realising her gaffe, flushed to the roots of her ginger hair. “Forgive me! You are Eored’s brother, the deer man.”

Deormund threw back his head and chortled; he wasn’t about to spare her.

“Deer man? Well, I’m not about to sprout antlers if that’s what you think!”

“Oh, come on!” Eored came to her rescue. “You know what Saewynn means.” He smiled at his betrothed. “He’s all right when you get to know him. It’s just that—” he bit his tongue, leaving them both curious.

“What?” she asked

“Ay, just that … what?” Deormund growled.

Eored racked his brains for a credible alternative. None came, so he completed his thought. “Just that he’s not used to a maiden’s company.”

From the expression on Deormund’s face, he knew he had blundered. Neither of them got another word out of the deer herder until they entered the wheelwright’s small home. Not that it mattered, because Eored and Saewynn chattered all the way, absorbed in each other.

“Here, Mother sent you these. She thinks you need fattening up,” he said, at last.

“Nay, my Eored’s fine as he is. Besides, after our wedding,” she gazed lovingly at her man, “I’ll care for him well. We’ll have no lack of freshly-ground flour for baking.”

“So, when—”

“August. I’ve spoken to Father and the priest,” she said quickly.

Deormund glared at his brother. “Don’t you think you should go home and tell our parents?”

“We’ve only just decided. We’ve been together since before Yuletide—it’s not been so long.”

“Ay, well, why don’t you two cross over the Swale with me when I take my new stag back?”

“You’ve still to capture it,” Eored pointed out reasonably.

“I can sniff a change in the wind. I’ll be hunting tomorrow and have you ever known us to fail?” He gestured to the hound stretched like a shaggy rug in front of the newly lit fire.

“Our Deormund knows his trade,” Eored said.

“Is it hard to catch a stag, Deormund?” the young woman asked.

He studied the oval face and thought, Eored’s caught himself a lovely hind. He appreciated the sincere interest in her eyes as she asked the question.

“Not if you tackle it correctly, Saewynn. That’s why I mentioned the wind.” He explained how he meant to set about it, casually throwing in the fact of the shed antlers.

“Ay, those would be a problem, I can see that. But what about when you’ve netted the beast? Doesn’t it take some controlling?”

“It does,” he eyed her figure, “it’ll weigh about twice your weight, but when it realises I mean it no harm, and it’s safely noosed, I shall lead it to the ferry. There are plenty of hinds on Sceapig to calm its nerves.” He said this without considering his audience. Again, she flushed, making him feel clumsy and insensitive.

“Well, it’s Nature,” he said defensively, earning himself a sweet smile and confirming his positive impression of her.

The three ate a pleasant meal together until afterwards, Saewynn declared she had to go home. The brothers agreed to meet the next day at the ferry, at midday, with or without the woman, according to her father’s ruling.

Deormund knew before rising that the wind had strengthened. He could hear it whistling around the roof of his brother’s house. Devouring the crusty bread not finished the previous evening, he decided not to wake Eored since the dawn had not yet broken. No problem with Mistig, already sitting by the door, eager to bound outdoors. Deormund obliged, unlatching the door, settling his pack on his back before following the deerhound along the road towards the Forest Ridge. It was a long march, hence his early start. If he wanted to meet his brother at midday, he had to consider the time needed for the return.

Mistig bounded ahead, occasionally halting to check on his master and racing up to him only to lollop forward again, continually repeating the performance.

Dozy dog, you’ll double the travel! Aware the hound revelled in exercise, he thought no more of it. After an hour of marching, the wind ruffling his hair and even snatching his breath away on occasions as it strengthened, he smiled to himself. Perfect conditions for capturing a stag.

He knew exactly where to place his net since this was the third time he had set out on a similar venture. Now the rising ground showed the forest on its ridge. That was his destination, just half a mile away. As he gazed up at the woodland, he imagined the activity therein at this time of day. Swineherds would be driving pigs along the main drove ways to the commons or dens. Deormund knew that in recent times, these clearings on the higher and better ground had become settlements. In the past, transhumance took place, the hogs could be many miles from the homestead; the changes made sense to him. Not that the villagers’ activities particularly interested him.

Instead, he’d arrived at the area of concern to him: the fringes of this chalkland forest. He led Mistig to a track between two stately beech trees, ideal for hanging his net. Under the scrutiny of the intelligent hound, he removed it from his pack and spread it untangled on the grass. Taking his twine, he tied it just above head height around both trunks before tightly attaching his dangling net at its top corners. Next, he took two wooden pegs from the bag and pinned the lower edge into the earth. He used his weight to press each down with his foot, not hard enough to fix the net too firmly but so that any prey driving into the net would pull it free to complete the entrapment. Once the operation was ended, with the sagging belly of the mesh on the ground, all studiously watched by the hound, he headed several hundred yards farther up the edge of the forest with the wind behind him—an essential detail, because the buck could scent more than a hundred yards upwind. That was why he chose a place downwind at a fallen tree, so that he could sit on the trunk.

Judging that a couple of hours had elapsed since the dawn, he decided that soon a stag would break from cover to cruise with the wind along the woodland margin in search of food—if not, he’d send Mistig to chase one out. The hound, trained for months to do this, had succeeded twice before. Deormund had faith in his companion who, so giddy when not stalking but dedicated when at work, now lay with bearded chin on his crossed front paws, staring studiously along the line of the forest’s edge. His master noted the gentle tremor running down the hound’s body, a sure sign that the dog was like a coiled spring, suppressing his excitement.

Mistig suddenly bounded to his feet and was away faster than the wind. The deerhound had seen the stag before his master had even suspected its presence. Deormund leapt to his feet, snatched up his bag and shouldered it as he ran, never taking his eyes off the pursuit. Trained to perfection, Mistig only revealed himself some twenty yards from the net. At that point, he barked and accelerated, cutting off the startled and speedy stag, which, in terror at the sight of the snarling grey beast, swerved into the trees for cover, not suspecting the trap. When its charging hoofs took the deer into the trap, its headlong rush and weight pinged out the two pegs, ensnaring the struggling creature in the netting. The more it struggled to free itself, the more it became entangled. When Deormund arrived, out of breath, the beast was kicking and writhing in vain.

The deer herder, not forgetting his debt to Mistig, found a piece of his mother’s sausage, preserved for the occasion, giving it to his worthy companion with words of gratitude and encouragement. Only then did he turn to inspect his flailing prize. It was a rusty red beauty: he reckoned, although the threshing about made it difficult to judge, that it stood about four feet, six inches tall. He would only be able to gauge its age by looking at its teeth; for the moment, he was happy to believe it was a five-year-old. This beast would have no trouble in ousting the old stag on Sceapig in the rutting season.

Ignoring the creature’s panicked attempts to free itself, Deormund took his knife from its sheath and cut the twine attached to the beeches. Far from releasing the stag, this manoeuvre entrapped it further so that now it lay in the net on the ground, its eyes bulging and terrified. The deer herder prepared a rope noose, knotting it to slide and tighten easily, leaving a leash of eight feet. He did not wish to sustain a similar painful blow from the beast’s hoof as on his first capture, which had left him limping for days and with a month-long bruise. Experience had taught him to be nimble and quick on his feet.

Now came the delicate part of the task: extrication. To do this, first, he took the loose end of the rope around the nearest beech trunk and tied it off, leaving the noose very large. Next, he knelt beside the animal and began to talk soothingly to it, making calm, reassuring noises as he freed the head and upper body from the netting, gently stroking the deer into stillness. The legs had to remain entangled until the last moment. As soon as he could, he slipped the noose over the beast’s head and tightened it carefully around the neck. The time had come to free the limbs, which he did bit by bit, until the animal was cleared of netting. Released, the stag leapt to its hoofs and made to bolt, only to pull the noose tighter still around its neck. There it stood, captured, trembling and uselessly shaking its head.

Ready to dedicate time to his equipment, he rolled up the net and packed it away, slinging his bag onto his back. Deormund then walked to the captive stag, where the creature shied away with the little slack the rope gave it. Gently, delicately, the deer herder stroked the velvety muzzle, soothing it again with murmured words. He noticed the nascent antlers, congratulating himself on an excellent morning’s work. His hand slid along the cord until it came to the knot at the trunk. Knowing that it had been pulled tight by the stag, he grasped the rope with his left hand, hooking it under his armpit for extra security while sawing at the knot with his sharp knife. No point in trying to unknot the cord after it had been so tightened. At last, he was through it, sheathed his blade and seized the rope, now a leash, with his right hand.

For the moment, he would need all his strength. Right about that, he dug his heels into the ground as the stag bucked and tugged to escape. Steadily, Deormund hauled the creature towards him, stepping back out of the woods as he did so. Realising that there was no escape, the deer turned and, as the herder hoped, walked towards him. The stag lowered its head in a classic threatening gesture, readying for the attack.

“You’d better not do that when you’ve grown your antlers, my beauty!”

Mistig dashed over and, placing himself between the stag and his master, bared his fangs and growled ferociously as the captive rethought its strategy. Again, it turned to flee, but Deormund held firm and drew the would-be fugitive back out of the forest. The battle of wills lasted half an hour but ended in submission, as Deormund knew it would. By that time, they had travelled a mere eighty yards.