3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

Christ Church Priory, Canterbury, 990 AD. Orphaned by vikings, Folcwin and his elder brother Aelfwynn have become excellent scribes.

Their lives, enlivened by sibling rivalry, are upset by a competition to illuminate a commissioned psalter. After Folcwin is selected the victor, his brother is accused of murdering another competitor, and he escapes. While Aelfwynn begins a patriotic battle against Viking raiders, Folcwin's fame as a scribe increases.

Even with their imbalanced fortunes, the paths of the two brothers are bound to cross with powerful kings and strong leaders, including King Aethelred, Thorkell the Tall and Edmund Ironside. But can they overcome the Viking menace?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

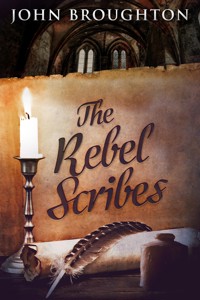

THE REBEL SCRIBES

TWO ANGLO-SAXON MONKS AGAINST THE VIKINGS IN CANTERBURY

JOHN BROUGHTON

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Epilogue

You may also like

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 by John Broughton

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Fading Street Services

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Apart from known historical figures, names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination. Other than actual events, locales, or persons, again the events are fictitious.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Frontispiece is by Dawn Burgoyne,

Asalph’s Psalm (Psalm 82) written in English Minuscules in the style of St Oswald’s Psalter a.k.a. the Ramsay Psalter.

Dawn Burgoyne, medieval re-enactor/presenter specialising in period scripts. Visit her on Facebook at dawnburgoynepresents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to my dear friend John Bentley for his steadfast and indefatigable support. His content checking and suggestions have made an invaluable contribution to

The Rebel Scribes

This novel is dedicated to the memory of:

Arthur Broughton MM 1896 – 1955

My grandfather, the first to evoke my love of history.

ONE

Christ Church Priory, Canterbury, 990 AD

Sibling rivalry! — that he could exploit, smirked Prior Hrodulf, mind whirling with the details of the strange encounter with Ealdorman Ansleth that he had just brought to a satisfactory conclusion. The nobleman had made a proposal, interesting from an economic point of view, but laden with conditions. Ansleth had a lovely daughter, fair of countenance, and deeply spiritual. She was destined to take her vows and enter the most prestigious nunnery in Kent—Minster-in-Thanet, founded by a Kentish princess who accepted land for a house of prayer as compensation for the killing of her brothers. She was granted as much territory as her pet deer could run around in a day. Ansleth did not expect his daughter, Imelda, to become a simple nun; he had wanted to be a proud grandsire but, respecting her vocation, the besotted father already imagined her as abbess in charge of her own religious house.

To give her a head start in her chosen career, he wished to make her a gift of the most beautiful psalter ever produced. Where better to seek the scribe-illuminator than in the priory renowned for such productions, namely, Christ Church Priory in Canterbury?

Prior Hrodulf considered the proposal and mused,

The orphans are ideal for the job.

Money for the production would be no obstacle for the ealdorman, who stipulated, too, a magnificent annuity for the priory coffers. However, there was one overriding condition, and it was to take the form of a test. Prior Hrodulf must select the three worthiest from among the brethren, who would not be mere scribes but also illustrators, capable of interpreting and illuminating the texts to the highest standard.

Hrodulf reran their conversation in his mind. Half-closing his eyes, he could visualise the grey-bearded warrior standing by the window, his back somewhat discourteously presented to the prior as he gazed out into the cloister and voiced his thoughts.

The gruff voice of the nobleman insisted,

“Whoever, I adjudge to be worthy of the task, Prior, must complete the whole psalter within two years of our agreed starting date.”

“But that, Lord Ansleth, is a demanding deadline! You do realise that the Bible contains one hundred and fifty psalms?”

“I know it well, Prior. I am seeking a skilful scribe who can also interpret and illustrate swiftly and to the most exacting standards.”

“What sort of test do you propose, Ealdorman?” The prior tried and failed not to convey the sudden anxiety in his unsure voice.

“Your three candidates will have one week to illuminate Psalm 82. If I am satisfied that the work is of the highest possible standard, then it will be included in the finished volume.”

This had been the prime condition and even now, alone, Prior Hrodulf marvelled at the astuteness of the Saxon nobleman. Somehow, he had chosen the most impenetrable of the psalms for the candidates to interpret. Surely, the ealdorman must have sought ecclesiastical advice because he came over as a rough and ready military man, not one seeped in the study and interpretation of the Holy Scriptures. Indeed, if pressed, the prior would have great difficulty explaining the meaning of that particular psalm: A Psalm of Asaph. He muttered the first six lines to himself:

And ran it through in his mind:

God presides in the great assembly;

he renders judgment among the “gods”:

“How long will youdefend the unjust

and show partiality to the wicked?

Defend the weak and the fatherless;

uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed.

Ay, that was how it started but he could remember no more, perhaps because the hardest, most inscrutable part continued until the end. His misgivings returned and brought him to the ealdorman’s second condition: he, Hrodulf was to refuse all help to the candidates regarding the interpretation of the psalm during their attempt. He thought:

Ho-ho! Little did he realise that I couldn’t guide them even if they asked for my aid. I have studied the Scriptures for a lifetime and their three ages summed together, he calculated the total— come to only a decade more than my three-score and seven. He sighed, and said aloud, “May God forgive me; I am old and unworthy to hold this position.”

He thought about his choice of candidates, the brothers, orphaned sons of the great warrior Heilan, who had perished at the hands of the Vikings in the raid of 974, which had ravaged much of the shire. Nobody knew the fate of the boys’ mother, most likely she had died, too, in the same incursions or had been abducted and sold into slavery. The prior shook his head sadly, the boys had come into the monastery years later, brought here by an uncle, who refused to sustain their upbringing any longer after nine years of fostering. His financial difficulties had been the priory’s gain because both showed ability as readers and writers. They were destined to become the fine scribes the famous scriptorium was crying out for in its endeavours to recover its renown jeopardised by the Norsemen’s plundering and the consequent declining pool of talent caused by a shortage of vocations.

The elder brother had displayed greater resistance to the calling, for he had eighteen winters behind him on entering the priory and was already proficient in arms. His distraction arose from youthful resentment born of the inability to fight alongside his father or uncle against the Vikings. Although a nine-year-old could not take a place in the shield-wall, during the 974 incursions, Aelfwynn had been capable of protecting his seven-year-old brother, Folcwin, and conducting him safely to his uncle’s house.

Rather than wishing to be a scribe, Aelfwynn insisted his destiny was to become a warrior, like his father. He was only dissuaded from this course by his poverty, which prevented him from purchasing a sword and body armour. This, together with an understandable reluctance to separate from Folcwin, allowed his talents to blossom in the priory at Canterbury.

The third candidate was a youth, just a year younger than the elder brother, the prior counted on his fingers, ay, he would now have a score and six winters to his name, who was Gerbrand. Being the same age, give or take, as the other two, he had formed a firm friendship with them, which had drawn him to the scriptorium and as God would have it—or had provided for—Gerbrand, too, was skilful with the pen. All three had finished their novitiate together, becoming monks at the same ceremony, perhaps driven on by a healthy rivalry. So, these were his three candidates. Before sending for them, he must obtain three psalters for their use. All three would illustrate Psalm 82 but only one would go on to transcribe and illuminate all one hundred and fifty psalms. He would make it clear to the other brethren, on the pain of strict penance, that nobody must make suggestions or discuss the psalm with the three competitors.

He chuckled to himself, delighted by the situation, but then frowned. Regarding the competition, their healthy rivalry should certainly produce outstanding craftsmanship. As he pondered on this and the eventual worth of the psalter, his earlier misgivings troubled him. It might be that the outcome would not be so positive. Prior Hrodulf was advanced in years and harsh in his judgment of himself, but in truth, his monks considered him a wise, kind and learned mentor.

TWO

Christ Church Priory, Canterbury, 990 AD

Out of the corner of his eye, discreetly, Folcwin glanced across the aisle of the scriptorium, where under the window opposite his, Gerbrand was painting a fine line in liquid gold. His companion was too far away for him to snatch an illicit glimpse of the design, so he sighed heavily. Hitherto, they had obeyed the prior’s order not to discuss their work, but each had tentatively admitted to having finished the copying of the text of Psalm 82, but that was no great achievement since the psalm was relatively short at only seventeen lines. Another glance and his thoughts shifted in another direction.

What’s he doing now? Green ink! Why? Can it be for grass or trees? But where? Why?

There could be no doubt that Gerbrand was further ahead than he. He sighed again, causing his competitor to raise his head and grin cockily his way. Cross with himself for encouraging an adversary, Folcwin bit his lower lip. He had no idea how his brother was doing because he had his back to him but Aelfwynn was sure to be more advanced in his interpretation because apart from the fact that Folcwin was stuck, in trouble, his elder brother was better at—well, everything: singing, running, Latin, socialising. Repressing another sigh, transforming it at the last second into a cough, Folcwin wondered desperately how he could illustrate a psalm he did not understand.

His eyes, so different from those of his brother with their dark grey-brown like hard oak bark, returned to settle on his parchment. Folcwin’s were a soft sage-green but one eye wandered, giving him a permanently distracted appearance, as if his spirit was on a journey to a place only he had glimpsed. He reread his transcription carefully and his front teeth almost drew blood from his lower lip as he concentrated. The beginning was easy enough, for the psalm asserted the supremacy of God over every supernatural power. Of course, he could draw God at the top of the sheet of vellum but that would win him no plaudits. It was too obvious. The ealdorman’s aim was for every page to be thought-provoking, the prior had explained to them, so nothing foregone: he wondered, didn’t that mean, too obvious?

Again, a sigh and it gained him another grin from across the aisle. Gerbrand was cleverer than he; of that, he was convinced. He was sworn to obedience and the prior had chosen him, so he must make more effort or, at least, pray for enlightenment. But could he do that without Gerbrand noticing his desperation? Where was the problem? Let’s see, there’s the problem, beginning verse 5:

The gods know nothing, they understand nothing.

They walk about in darkness;

all the foundations of the earth are shaken.

That was what he could not reconcile: first, the psalm insisted on one supreme God, then its composer had thrown in these gods. The psalmist went on to say these gods were the sons of the Most High but that they would die like mere mortals.

Scratching the hair at his temple, Folcwin set about a promising train of thought. Didn’t Genesis use the term sons of God to refer to angelic beings? He reached for the Bible; each of them was allowed a copy to consult. Deliberately opening it at random to mislead Gerbrand who was staring curiously across at him, he leafed backwards through the Holy Book as if searching for something until his rival’s attention returned to his green ink. Then he opened the beginning of the Scriptures, and there it was! Genesis 6:4—

The Nephilim were on the earth in those days—and also afterwards—when the sons of God went to the daughters of humans and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown…

In the margin, in ink, in the tiniest writing, someone had noted a cross-reference to Job1:6 and when he turned to it, sure enough, it referred to angels presenting themselves before the Lord.

Now he was convinced that the gods mentioned in the psalm were angels. In the absence of any other idea, he would do his best possible illustration of angels presenting themselves to God. What had he to lose? In any case, if quizzed on it, he could make these two citations. It would save him the ignominy of proffering just the text. Also, as far as he could interpret, his solution was not foregone. But he was not a prior, abbot or archbishop, he thought angrily—nay, not even an Aelfwynn!

Were there other possible interpretations, he wondered. What were the other two up to? There were sure to be, but he could not think of them. Relief flooded over him and he could not resist a triumphant smirk in the direction of his friend, who scowled back in anything but friendly fashion. Well, he’d show them both!

In an hour, he had pricked out the outline of his main figures and by Sext, he was ready to eat and afterwards start his design with coloured ink. Raising the hinged top of the desk and carefully conserving his vellum within, he turned the key and slipped it in his pocket. He’d never done anything so cautious before, but he didn’t want his idea stolen.

He stood to head for the refectory and to his astonishment, his brother lurched forward in his seat to cover his work with both sleeves of his habit.

“I’m not trying to steal your ideas, Aelfwynn!”

“I’m taking no risks, brother. I’ve worked out the hidden meaning in the psalm.”

“Hidden?”

“You go on ahead, I’ll join you at the table.”

He looked anxiously at the approaching Gerbrand and made sure his sleeves left no gaps to provide a glimpse of his winning interpretation.

“Hidden?”

Gerbrand had caught the word.

“I hope you sanded your ink before draping all that cloth over it!”

A look of panic, followed by a glare at his brother and Aelfwynn said,

“You’d better not have made me smudge or I’ll beat you senseless.”

“Charming! I haven’t done anything. I was just going for a bite to eat.”

“You were trying to pry, being as you are so clueless.”

“Hush!” another of the monks hissed, “Some of us have to concentrate. Silence! Or I’ll report the three of you to the prior.”

The threat was enough for Folcwin and Gerbrand to move away and leave Aelfwynn to check his work and put it in safekeeping. There was no smudge as he had imagined because he had been staring at the parchment for a while in search of inspiration. He had been checking Exodus 21 and 22 and was sure that he had understood the psalmist’s meaning. All he had to do after lunch was translate the idea into an image. Food should provide him with the mental energy he needed. Was he mistaken or did his annoying brother seem more cheerful and confident? He hoped not, because he considered his friend, Gerbrand, to be the greater threat in this competition. Absolutely, Folcwin was a neat scribe and had a fine, precise hand at illuminating but the Almighty had not blessed him overly with intelligence. How could his brother be an obstacle to his inevitable triumph? For example, the puny wretch would never have thought of that passage in Exodus—he probably thought the gods in question were Woden, Tiw, and Thor! He’d most likely make a laughing stock of himself before the prior and the ealdorman; Aelfwynn almost, but not quite, felt sorry for him.

Finding his competitors already seated at the table and tearing at some oven-fresh crusty bread before dipping it in a delicious-looking vegetable soup, he ladled some for himself from the large iron pot set before them.

“So, how did it go this morning?” he asked cheerily with confidence designed to intimidate.

“Great!” Folcwin chirped. “I finally realised what the psalm is about.”

“Did you indeed? Well, aren’t you the clever one?”

“Not really. I was beginning to lose hope when it came to me in a flash of inspiration.”

Gerbrand grinned and said without a trace of malice,

“It must have been the Holy Spirit that inspired you, Folcwin. In which case, what chance have we mere mortals?”

Aelfwynn looked keenly at his friend, hastily swallowed his piece of bread, and asked,

“Are you quoting directly from verse seven, Brother Gerbrand?”

The young monk looked surprised; he hadn’t meant to quote at all. If anything, he wished to avoid discussion about the psalm for fear of giving away his interpretation based on his reading of Saint John’s Gospel. Aelfwynn was as sharp as the blade of King Aethelred’s sword, however reluctant the king seemed to use it. The same could not be said of his rival’s insightfulness. The elder of the brothers must be favourite to win this contest and illustrate the whole psalter because he was the brightest among them and if he, Gerbrand, gave him the slightest clue to his thinking, Aelfwynn would pounce and adopt it as his own. So, there could be no loose talk. Cautiously, he asked,

“Verse seven?”

“Ay, mere mortals you said. In the psalm, a clear reference to the gods. Have you worked out who they are, these deities?”

“Maybe I have! But I wouldn’t tell you if I had!”

“How mean-spirited of you! Now,” he said, his voice exuding sarcasm, “you can say what you like about Folcwin, but he isn’t mean. Are you, little brother?”

Aelfwynn was bigger and stronger than he, but Folcwin did not like to be mocked about his size. Secretly, he had been lifting heavy stones that the brothers had placed as a rockery in the herb garden. He’d been lucky not to have been noticed so far, but the hardened muscles, hidden under the sleeves of his habit, were beginning to please him. Not that he felt capable of challenging his tormentor in any physical contest just yet: maybe one day!

Mildly, he smiled at his brother and in a low voice said,

“Nay, I don’t think I’m mean, Aelfwynn.”

“So, tell us then, wise little brother, who were these gods referred to in the psalm?”

Folcwin smiled again, seeking to avoid any provocation, said gently,

“Come now, brother. It’s not mean spiritedness, but you must remember, the prior has forbidden us to discuss our interpretations.” Then, he deliberately sounded defeated, “Anyway, what chance is there of me getting the right answer? I’m not as smart as you two.” He bestowed his studied unhappy expression on Gerbrand, too.

The ever-cheerful Gerbrand smiled at him,

“Don’t be so resigned, my friend, inspiration can come to anyone humble enough to receive it.”

“Humble,” Aelfwynn chortled, “no problem there then! Froddy’s got us both beaten, he’s positively lamblike!”

Gerbrand did not like it when Aelfwynn tormented his brother. He preferred them to be happy in their friendship.

“Come now, Brother, blessed are the meek said Our Lord and he is known as the Lamb of God.”

The elder brother sneered and revealed the worst of himself,

“Perhaps we should nail Froddy to a tree!”

“Hush! How you exaggerate! Were anyone to overhear you, you might be accused of blasphemy. We know you are only teasing Folcwin, but it would be better if you let him be.”

Aelfwynn sneered, broke off a piece of bread, and threw it at his brother’s head, who caught it deftly and dipped it in his soup.

“Thank you!”

But whether that remark was for the bread or the moral support from his friend was unclear to either of the two young monks.

Gerbrand looked anxiously at Aelfwynn. The elder of the brothers was a good companion but there had always been a rough edge of bitterness to his character, which most likely was due to being orphaned at a young age. Even so, Gerbrand had always admired his intelligence and despite these occasional excursions of tormenting his sibling, he liked the normal fierce protectiveness he showed towards Folcwin. Today’s behaviour was probably to be ascribed to his desire to assert his authority as the oldest among them and, naturally, to the yearning to succeed in this prestigious competition.

I wonder how he’ll take it when I win the contest? I hope it won’t destroy our friendship.

He had no worries about Folcwin, he truly was a meek character and he doubted that he feigned humility. If anyone could accept being bested, it was Folcwin.

THREE

Christ Church Priory, Canterbury, 990 AD

As they slouched out of Prime, Folcwin glanced at Gerbrand, whose morose expression struck him as unusual for their ever-cheerful companion. He sidled up to him,

“What’s up?” he whispered, “Why the long face?”

If possible, his countenance grew even more doleful,

“Good news for you! I’m withdrawing from the contest.”

“What! But today is the last day!”

“I know, but yesterday I realised I got it all wrong. My interpretation is erroneous and there’s no time to change now.”

His face suddenly brightened,

“At least it means that I have the day free, instead of poring over that blessed parchment.”

Folcwin’s emotions were mixed. A shameful part of him exulted because his chances of being judged the winner had increased but a nobler trait despaired for his friend.

“The work’s done, you might as well submit it. Your presentation might be acceptable to the ealdorman. You can’t be sure.”

“Thanks, Folcwin you are a true friend. In any case, I have things to do today. Good luck with your page.”

And that was the last he saw of him.

Vaguely aware of his brother at his back as he settled into his place in the scriptorium, he stared at the almost completed document when a strange impulse seized him. Why not abandon the idea of leaving a white margin around the page? He could fill the vellum to its very edge with rich entwined foliage and blooming flowers. That would avoid a portion of white background, creating a sumptuous, exciting effect. This disquieting inspiration had implications. It meant he would have to work hard all day, most likely doing without lunch because if he left even an inch unfinished, the result would be so counter-productive: as immediately noticeable as a person with a black eye, and the fine detail it necessitated could not possibly be rushed. He took a deep breath, put his tongue between his teeth and began this brilliant self-imposed task. At once, he could see the merit of his scheme as the winding foliage gave completeness to the whole, leading the eye into the text and, essentially, the joyous visages of the angels.

Surely, now, I will win!

Deep in concentration and driven by a fervid desire to finish the page, Folcwin lost all sense of time until the tolling for Sext reminded him that it was midday. He felt a tap on his shoulder and looked into the smiling face of his brother.

“At last, I’ve finished!” he said, making it obvious that there was no attempt to sneak a glance at his younger sibling’s work. His deliberate nonchalance was his way of imposing his confidence in victory. “So, I can relax now. How’s it going, anyway? No nearer to finishing?”

“I’ve still got a lot to do.”

“All right, I’ll see you in the refectory, later.”

“I don’t know about that. I have only until the Vespers bell to complete the page.”

“Right to the last minute, eh, little brother?”

Aelfwynn’s sneering tone grated with Folcwin, who was pleased to hear the sandals pad away so that he could concentrate again.

By mid-afternoon, with the chiming of the Nones bell, he knew for certain that he had three hours left to finish the margins. His eyes felt dry and sore and his shoulders, hunched over his work, ached, and cried out to be rolled and stretched. Nothing for it, he had time enough to finish and, masking the unfinished margin with his hand, so it did not strike his eye, he marvelled at the beauty of his creation.

Ealdorman Ansleth won’t be able to fault my skill. If my interpretation is right, I’m sure to beat Aelfwynn—and what a blow that will be to him!

Smirking to himself, Folcwin set to again after rubbing his eyes and another hour flew by, leaving him with another two, although he did not know it, and two inches of margin in the bottom corner.

Suddenly, he heard a gasp at his shoulder and looked up into the smiling face of one of the older brothers.

“Your psalm is magnificent, Brother Folcwin,” said the chandler. “But you must come with me, Prior Hrodulf wishes to speak with you forthwith.”

“But I haven’t finished here, and it will soon be sunset!”

The candle-maker looked scandalised.

“You must not disobey Father Prior’s command!”

Folcwin’s face tensed in agitation but he took his parchment and locked it in the desk and leapt to hurry unwillingly to the prior’s quarters.

What the devil does he want at such an inopportune moment?

He knocked on the heavy oak door. Always amazed that anyone could hear his puny knock through that solid wood, but sure enough a muffled voice reached him,

“Come!”

“Father Prior, you wished to speak with me? The thing is, I only have till the evening bell to finish my page,” he blurted, looking anxious. At once he regretted his impertinence as the elderly monk’s eyes flashed their annoyance and his lips flattened.

“Some things are more important than book illumination, Brother Folcwin! Can you account for your movements today?”

The young monk gaped at his superior. What was this, an interrogation? It was. He laughed, but it was a false, forced sound even to his ears.

“Movements? Father, you jest!” He bit his tongue. He was being flippant and impertinent, and it displeased the man who could inflict severe penance if he so chose. Hurriedly, he said,

“Please forgive me, Father Prior, I am not myself today. The need to complete my work bears down on me!”

“Answer my question unless you wish to arouse my ire!”

Folcwin gulped, looked contrite and in his most servile voice, replied,

“I have not moved from my desk in the scriptorium until our brother chandler told me to present myself here. I chose not to eat lunch because time is pressing to finish—”

“Ay, ay!” the prior snapped, “So, the brothers in the scriptorium can verify your story.”

“Story? It’s the truth, I swear!”

The prior took a bible from his desk.

“Place your hand on the Bible and swear that you have been in the scriptorium all day and nowhere else.”

What the devil’s going on?

He laid his hand on the tooled-leather cover,

“I swear in the name of God the Father that I have been in the scriptorium all day and never moved until a few minutes ago to come here.”

“Good! Of course, I shall check with the other scribes.”

“Father Prior!”

Does he think I’d perjure myself?

He recovered his composure,

“May I ask—”

“You may. Brother Gerbrand has been found dead by the river.”

Folcwin paled and gasped. He had spoken to him after Prime and at once told the prior as much.

“You will understand, Brother, that nobody had any reason to murder Gerbrand, except for you and your brother, Aelfwynn—”

“For a psalter!” Folcwin glared, conveying his outrage. But even as he spoke, the worm of doubt wriggled in his stomach, making him feel sick.

Is it possible that Aelfwynn could perpetrate such a heinous crime?

He dismissed the thought at once and said,

“There must be some other explanation, an accident? Some misadventure? Aelfwynn would not harm a crane fly! And I have been illustrating all day.”

“Our investigation will reveal the truth, Brother. You may go.”

Folcwin hastened back to his desk and heart pounding strangely, feared to raise his quill, lest he ruined his work through the distracting thoughts that tormented him. His best friend, apart from his brother, was dead! Thanks to his numbed state, he hadn’t had the presence of mind to ask the prior how Gerbrand had died. The elderly monk had mentioned the fast-flowing Stour. Had he drowned, or been held under? Gerbrand was Aelfwynn’s dearest friend, too. That he had murdered him was inconceivable!

The doubt returned, for what did he know? He could not vouch for the movements of either monk since his concentration had been fixed all day on his manuscript. Talking about which…he could only pray that the Lord would quieten his thumping heart so that he could complete the last inch or so of his margin. His tongue returned between his teeth and although he could not chase away the image of his cheerful friend’s face from his mind, he managed to maintain the high standard of his work, finishing the last sweeping flourish of foliage only a few minutes before the eventide bell called the brethren to worship. Sprinkling white powder on the fresh ink, he blew it off, examined the manuscript inches from the tip of his nose. Satisfied, he grinned at the masterpiece with the conviction of impending triumph. But this sensation was instantly replaced by the anguish of loss. Grief swept over him like the racing current of the Stour, he imagined it closing over his friend’s helpless body. Surely, there had been an accident? Nothing else made sense. With a last glance at the vellum, he locked it away and hurried to the service. At the chapel door, he spotted the tall figure of Aelfwynn entering, his head above those of his companions. So, he was free to pursue his usual activities but if a murder was suspected, inevitably, the shire reeve would question everyone. Well, he had nothing to fear, except for not winning the psalter competition.

At the end of Vespers, the prior made an announcement, revealing the sad demise of Brother Gerbrand to the consternation of the congregation. Their superior explained that foul play could not be ruled out and therefore to expect a full investigation on the part of the authorities. This speech ended by him ordering Brothers Aelfwynn and Folcwin to his quarters immediately after the service.

Throughout the announcement, Folcwin had not taken his eyes from his brother’s face. Noticing Aelfwynn’s reaction to the news of Gerbrand’s death, he did not doubt his innocence. At the prior’s words, his brother’s face had assumed an ashen tinge, such that Folcwin would have wagered anything he possessed—not that that amounted to much—on his not being guilty. In any case, the whole concept of murder for a competition was utter folly as far as he was concerned.

The two brothers met outside the chapel. Aelfwynn was still grey-faced and looked years older than his score and seven years.

“It can’t be true! I saw Gerbrand this morning. He can’t be dead!”

“Same here. I know, it’s unbelievable!”

“We’d better hurry to the prior’s rooms. I suppose the competition is off.”

“I expect so,” Folcwin concurred sadly.

They found a beaming Ealdorman Ansleth to greet them in the prior’s quarters and they exchanged perplexed looks. Surely, life could not proceed as though nothing had happened in the face of tragedy?

Prior Hrodulf took charge of the situation at once,

“Brother Folcwin, the scribes have confirmed your presence among them all day, to my satisfaction. Although let me be clear on this, I never once doubted your oath on the Sacred Book. So, Brother, you are no longer under suspicion, whereas…” he stared hard at Aelfwynn, “You, Brother Aelfwynn, will be able to explain yourself to the shire reeve and if your conscience is untroubled…” he held up his hand to prevent the young monk’s protests, “…I was about to say, you will clear your name. Now, Brothers, Ealdorman Ansleth, as you know, is here following our agreement and wishes to proceed to adjudication. I have already made arrangements for Brother Gerbrand’s work to be brought for consideration…” he raised his hand again, “Ay, I know. He will be unable to complete the psalter if his presentation is judged the best, but one of you two will be able to continue our brother’s work in that case. Now, please go, collect your respective pages and bring them here.”

They hurried to the scriptorium exchanging opinions about the day’s incredible events.

“It’ll be interesting to see what poor Gerbrand produced—"

“Aelfwynn, his brother stopped and clutched a sleeve, causing the taller man to halt in his tracks.”

“What is it?”

“Swear to me you had nothing to do with his death.”

The colour drained from Aelfwynn’s face and an incredulous expression clouded it.

“Folcwin! Of all people! Surely you don’t believe that I could have harmed our friend? He was like a brother—er—like you for me. Besides, I’m not sure I want all that hard work for two whole years! As far as I’m concerned, little brother, you can win the competition with my blessing.”

Folcwin looked into his brother’s face. Nobody knew him as he did, and he could not detect the slightest insincerity in that earnest visage. What he did see, understandably, was anxiety. Aelfwynn would have to prove his innocence to the authorities.

“I believe you, Aelfwynn, of course, I do. But you’ll have to answer for your whereabouts. I told the prior the truth— that I had no idea where you were. I still don’t, but I believe you wouldn’t harm Gerbrand, so I’m not even going to ask, for fear of insulting you.”

“Thank you, brother. Come on now, we can’t keep the prior and the ealdorman waiting.”

Inside the scriptorium, they found the chandler again, grumbling, with a ring of keys in his hand. He was standing at Gerbrand’s desk, trying one key after another, in vain, and clicking his tongue in frustration until, “At last!” he cried, opening the lid, and lifting out a page from the desk, which he rolled loosely so that the brothers could not see the monk’s work. They retrieved their own and returned with the chandler towards the prior’s quarters.

“Bad business!” the chandler said, “Brother Oslac found him, you know the thin-faced fellow from Sussex who works in the kitchens? He’d gone to check the fish nets and discovered Brother Gerbrand floating lifeless, face down in the river. His soul had flown to heaven. Oslac says the back of his head was bloodied.”

“Does he, indeed!” Aelfwynn growled.

“It must have been an unfortunate accident,” Folcwin refused to believe anyone would harm the good-natured Gerbrand. Even so, he shot a suspicious glance at his brother. Where had he been all day, whilst he’d been completing his margins?

“Ay, it may have been,” the chandler agreed. “The sheriff will get to the bottom of it, that’s for sure.”

Admitted to the prior’s room, the brothers waited anxiously, each clutching his page to his chest.

“Let’s honour the memory of Gerbrand by scrutinising his production first,” the prior instructed. The candle-maker unrolled the parchment and spread it on the table. As one, the men in the room gathered round and the prior carried over a candelabra with four of the chandler’s creations casting their light on the inked vellum, causing the gold illumination to shine brightly. The two competitors frowned at the work but not for envy of its undoubted beauty, but rather neither could understand the interpretation; however, the prior could. He chuckled and said,

“Gerbrand is a great loss to us. Apart from his cheerfulness, which will be sorely missed, see how his intelligence shines through. Here, he refers to the Gospel of St John, verse 10. He interprets the gods of the psalm as the Israelite community receiving the law at Sinai. See, here, this clearly evokes Jesus’s allusion to those to whom the word of God came…John 10.35.”

Folcwin’s heart sank. He hadn’t thought of that! He glanced at his brother and was surprised to see a confident smile. He followed his brother’s gaze to the ealdorman who was shaking his head and muttering.

“Don’t you like it, Ealdorman?” the prior asked, unable to conceal his astonishment.

“Oh, ay, I like it all right. It’s beautiful, but it’s wrong! Let’s see what the others have for me.”

Aelfwynn pushed forward and laid a psalm written in the same elegant minuscule that Folcwin had chosen, different from Gerbrand’s more archaic rustic capitals calligraphy. Being present in body and spirit, unlike their deceased friend, Aelfwynn could explain his meaning himself.

“I do not agree with poor Gerbrand’s reasoning— although I can see its merits,” he added hastily, “I took the gods to refer to the judges mentioned in Exodus 21.6 and 22.8.” He pointed to the illustration of a group of three excellently depicted figures, “these here are my human judges as the prophet explained them.” He glanced anxiously at the ealdorman, who was already shaking his head, “But I must admit that as late as yesterday, I began to have my doubts about this interpretation.”

“In fact,” said the nobleman, “it’s not the one I seek for my psalter, but I believe you have produced a very worthy attempt, Brother. My congratulations!”

Aelfwynn nodded in acknowledgement of the compliment and stood aside, as curious as the others to see what his sibling submitted.

Folcwin smoothed out his sheet of vellum, to the collective gasps of those present. The outstanding beauty of the work could not be gainsaid. The dense colouring of the writhing margins had been a genial inspiration, Folcwin basked in how it exalted the figures and writing within.

“That’s it!” cried Ealdorman Ansleth, “This is my scribe! You’d better explain your thinking, young man, although I can see it matches mine own.”

Folcwin beamed, but avoided meeting his brother’s eyes,

“Well, I remembered the Book of Genesis 6.4 that referred to the sons of God of the psalm as angelic beings some of whom would, as Daniel tells us, appear to rule as princes over nations.”

“Ay, indeed! The prior’s voice rose in exultation, “As in Daniel 10 verses 13, 21, and 22!”

“That’s it!” The ealdorman held out a hand to Folcwin, “as also in Job 1, 6.” The monks each produced a startled expression at the layman’s knowledge. As for him, he wished to show that he knew what he was judging, for he’d had it on the highest authority in the Church: not that he would reveal that. “I have my scribe! You, young man, will illustrate my daughter’s psalter to the glory of God and Christ Church Priory, too.” The outstretched hand seized Folcwin’s and wrung it enthusiastically. “Congratulations, Prior, on the exceptional standard of your scribes.” His gaze embraced Aelfwynn as he lavished praise. Even as he did so, his hand was freeing a bulging purse from his belt. He tossed it on the table beside the exquisite parchment.

“You know my deadline, young fellow, but consider Psalm 82 done. Will you start at Psalm 1 and work through them in order?”

“Nay, Lord I’ll begin with my favourites first and then go back to the beginning. I love the psalms of David, best.”

This brought a beam of approval from the prior whose personal favourite had always been Psalm 23. How appropriate to think of those verses on this mournful day. The prior shuddered. Just when he should be celebrating the good fortune of the priory, he had to contemplate the possibility that there was a murderer in this very room. His gaze lingered on Aelfwynn’s face, but all he could detect there was an unexpected emotion. He seemed to be sharing in the happiness of his younger brother. How very strange! Not envious, then? Unless, thought the prior, he had believed the dead man a threat to his or his brother’s hopes. He sighed. He must trust in the law. In the end, justice would take its course.

FOUR

Christ Church Priory, Canterbury, 990 AD

Fired with enthusiasm, Folcwin hurried to the chapel before the first rays of sunlight stirred the slumbering cockerels. By offering his thanks at Lauds, he hoped to have a productive day with such an early start ensuring that by Vespers he would have another psalm completed for the lady’s psalter. Out of habit, he searched the congregated brethren for his brother but, of course, with this service not obligatory, as was Prime, he would still be asleep.

Leaving the chapel with a sense of peace and purpose, Folcwin strode to the scriptorium under a pink and grey sky. The inspiration he had prayed for in the church was here outdoors, within his grasp: to be seen in the roseate clouds, heard in the chirps, cackles and crowing of the birds greeting the sun and felt on his face as the sunlight bathed him in warmth. Only yesterday he had announced that he would begin with a psalm of King David. Most of the psalms were composed by him, so the choice was vast, but that king of Israel had praised God with joy for the new day. He recited the beginning of Psalm 108.

My heart, O God, is steadfast;

I will sing and make music with all my soul.

Awake, harp and lyre!

I will awaken the dawn.

That was the psalm he would copy and illustrate today. He would begin with a striking large capital M illustrated with birds lit by the sun. On entering the room, the provisioner, otherwise known as the amarius, the monk in charge of the scriptorium, greeted him with a strange smile and a sardonic tone.

“This way, your lordship. Everything is prepared for your comfort!”

Folcwin stared at the elderly monk, what was the matter with him? Brother Godfrey had always treated him kindly, indeed they had never exchanged a cross word or sour looks, so what lay behind this pinch-faced attitude?

As he took his place at the desk shown to him, he felt the hostility of the older man but tried to shrug it off with a cheerful and banal,

“It looks like it’s going to be a lovely day.”

“One day is the same as the next in here.” The monk reached into a deep pocket and pulled out a slim volume with a green tooled-leather binding. “Only the best for his lordship!” He tossed the book irreverently before the perplexed Folcwin.

“What’s this?”

“A book.”

Folcwin could take no more of the provisioner’s vile mood.

“If I have done something to offend you, Brother, it would be better to have it out with me.”

“Offend me? Nay. Unless you consider that these special attentions imposed on your behalf are an offence.”

“Attentions? For my benefit? Speak clearly, Brother!”

“Oh ay, when in my long years in office has anyone been mistreated within these walls? Yet, the prior sees fit that I rule your page for you. That I seek out Jerome’s translation,” he pointed at the green-bound psalter, “and that I rise early to prepare your inks and sharpen your quill. When in all my time has anyone been accorded such privileges?”

Folcwin gazed into the gentle features sadly contorted by dislike.

“I beg your pardon, Brother Godfrey, I have sought no preferential treatment. You are an institution here; someone I look up to. I am a mere, humble scribe come to obey the prior’s instructions.”

Somewhat mollified, the elderly monk forced a smile,

“As do we all, Brother. My orders are to ensure that you have everything that you require. I have chalked your vellum and you should be able to begin your work. If you need anything, it appears that I am at your beck and call.”