3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Sprache: Englisch

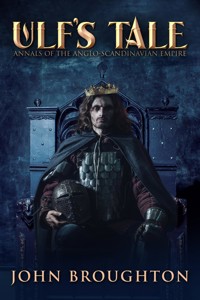

Amidst the bloodshed of 11th century combat and conquest, Saxon Godwine elevates himself from landless youth to trusted confidante of the most powerful man in England.

A kingmaker, Godwine's fealty propels six monarchs to occupy the English throne in his lifetime. But the pursuit of power is not without peril, and his skillful diplomacy and battle prowess are constantly tested by the schemes of distant, formidable enemies.

His allegiance to the monarchy pledged by sward and sword, Godwine seeks to maintain his influence as the Normans attempt to thwart him. Beset on all sides by bold and bitter adversaries, who will prevail?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Sward And Sword

The Tale of Earl Godwine

John Broughton

Copyright (C) 2018 John Broughton

Layout Copyright (C) 2020 by Next Chapter

Published 2020 by Next Chapter

Edited by Lorna Read

Cover art by Cover Mint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Special thanks go to my dear friend John Bentley for his steadfast and indefatigable support. His content checking and suggestions have made an invaluable contribution toSward and Sword.

Glossary

Aetheling: a potential heir to the throne, generally of royal descent.

Burh: a fortified town

Fyrd: Anglo-Saxon levied fighting force

Hide: a land unit of variable acreage

Hundred: an administrative area of about 100 hides; a subdivision of the scir.

Jómsvikings: an order of Viking mercenaries or brigands of the 10th century and 11th century.

Moot: a meeting

Nithing: a coward, a man of no honour.

Scir: a shire

Scop: a bard or poet

Thegn: a landowner and fighting man, many, like the horse thegn, had a specific duty on the noble's estate.

Wends: a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas.

Wergild: blood price; payment for killing or maiming, according to rank.

Witan: the king's council, made up of nobles, bishops and thegns

Witenagemot: the meeting of the Witan

I have used modern place names to aid readability, with these exceptions:

Places:

Cumtun: Compton, Sussex

Brighthelmstone: Brighton

Selsea: Selsey, Sussex

Hamtunscir: Hampshire

Heidaby: today's Busdorf municipality, Haddeby County, in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany

Skåne: Scania County, southernmost county in Sweden

Upsal: Uppsala, Sweden

Chapter 1

Cumtun, Sussex, 1009 AD

I'm the first to admit I have not lived an exemplary life. In all honesty, I've acted my entire existence out of self-interest, which is the price paid for leadership. I have a natural ability in that respect, born of my impressive personality and physical courage. Would it not have been a wasted life, had I not taken action and decisions to seize personal advantage from the portentous circumstances surrounding me? This is my story and I will not gild it like the Norman witch, who paid a lickspittle to write her Encomium Emmae Reginae: a paean to Queen Emma – dross!

More than any other, and at an impressionable age, one event shaped my character. I will not hide behind it since it explains what drove me to become the most powerful man in England.

The year was 1009 and I had but eight winters behind me. My childhood had been carefree and privileged as the first son of Wulfnoth, a mighty and well-connected thegn with estates at Cumtun, upon the greensward of the rolling hills of Sussex. My fondest infant memories are of the farmstead with the animals I helped feed, rear and slaughter.

But in the summer, it might have been late-August, while Father was away at sea, men bearing the crest of the Aetheling Aethelstan overran our lands. Those men seized Mother and me and turned us out on the road. They accused my father of high treason and the commander of the Aetheling's force labelled us “Wulfnoth's whore and whelp” and added, “who had to suffer.” What could I do? A boy of eight against a troop of warriors? Seething with shame and resentment, imagining what I would have done had I been a grown man, I trudged behind Mother as we made our way to seek more friendly faces in the town of Winchester, where my beloved Downs find their western end.

There, Father's cousin related his understanding of the events leading to our expulsion. My father was one of the commanders of the fleet of three hundred and ten longships stationed off Sandwich to protect the country from Viking raiders. I now know what my cousin did not at the time. It was an age of intrigue, when the cunning, sly counsellor, Eadric Streona, was a prominent man at Court. This villain took it upon himself to destroy those whom he presumed stood in the way of his advancement.

His brother, Beortric, another leader of the fleet, was no better and I believe he trumped up charges against my father, incensing him to mutiny, causing him to take with him twenty longships. The accusations were unjust but my parent ought not to have turned to piracy, raiding along the south coast, wreaking every kind of harm. When a member of this family becomes vexed…

Beortric chased after my father with eighty ships, vowing to bring him to account. But his vessels foundered in a violent storm, typical of the Channel, to be cast ashore – so much for Beortric's seamanship – only to be burnt by my father, who meted out his own justice. Hearing of this misfortune, King Aethelred fled to London, leaving the reduced fleet in confusion in Sandwich. The crews decided to row down the Thames to London. Hence, there was no deterrent against the Danes, who duly invaded Kent at harvest time and ravished Canterbury. That is why Father was outlawed and our lands confiscated.

“Cousin Leof,” I squeaked, “when I'm a man, I'll wrest back our estates and more besides.”

I think his bemused laughter did as much to harden my resolve as the events themselves. I owe a great debt to Leof, a wealthy merchant, trading in iron tools, leatherware and textiles out of Bosham in exchange for goods from the continent. He was also a wise and patient man. My restless, fiery spirit must have taxed this virtue. But not only did he accede to my request for lessons in swordsmanship, he also found me a veteran Irish campaigner who boasted, 'No Viking ever bested me'.

Cousin Leof gifted me my first sword, forged in Frankia. My copper-haired tutor, thickening at the midriff, was no longer nimble on his feet – just as well, given I was but a boy of eight. What he lacked in physical attributes, he compensated with a natural bent for tutoring. Ronain, the name he went by, had the gift of eloquence. He made me laugh and never fanned my always smouldering and ready temper into flames. For this reason, I admired and learnt from his quick wits. I ascribe my prowess with arms to his unbridled disrespect for orthodox fighting. He taught me the advantages of surprise and cunning and his motto, 'All's fair in battle', has ever been my byword.

A profound affection grew between the two of us. Ronain was determined I should develop into a warrior ahead of time. For my part, I resented his slave-driving methods, involving my running with two logs under my arms while he looked on, quaffing ale in the doorway of a nearby tavern. Woe betide me if I took advantage of any distraction – it always ended up with double the workload: turning cartwheels and other exercises, often to his advantage, such as making me chop logs or saw lengths of timber for his hearth. I admit it all served to develop muscles and add inches to my height.

The most important lesson I learnt from Ronain was one he would not have suspected. Given my quick temper and his soothing quick wits and ready laughter, I curbed my temper and channelled it into ready ripostes – Irish-style. This would stand me in good stead for the rest of my life.

Occasional news of Father reached Winchester; snippets, rather than anything satisfying. I did not see him for four years because, outlawed, he had joined the Danes in a place called Gainsborough, where the laws of King Aethelred could not penetrate.

The Danelaw welcomed the invading army of King Sweyn Forkbeard, bent on revenge for the massacre of his fellow Danes, notably in Oxford, instigated by the cowardly Aethelred. Should anyone blame me for wishing to become one of this wretched monarch's enemies? I felt ready, being on the threshold of manhood, to test my newfound battle skills. In 1013, therefore, I joined my father and King Sweyn to help his quest to remove the kingdom from its inept, characterless ruler. My journey was a risky undertaking in those lawless days, especially for a raw youth, but I reached my destination on one of uncle's horses, where a joyful reunion with my father took place that changed the course of my life.

Chapter 2

Gainsborough, Lindsey, 1013 AD

If anyone had told me as I entered manhood that my bitter, lifelong enemy would be a woman, I would have laughed in his face – I swear it's the truth. More dangerous than a berserker Viking, her sharpest weapon is a lying tongue that can make a man believe the Sun sets in the East. When that woman is also a queen, the peril is yet greater. I call her the Norman witch, although her real name is Emma. Whether she practises witchcraft I know not, but I am as sure as the river flows to the sea that she is evil and ambitious. If we Saxons are not careful, she will steal our own land from under our noses.

At this point, I need to explain how fate led me to the person who inadvertently ensured my wyrd would be entwined with that of the said Norman witch. It began when I arrived in Gainsborough, a thriving trading port on the River Trent and Danish stronghold in Lindsey. Having sailed from Sandwich up the Humber to Gainsborough, King Sweyn Forkbeard proceeded to conquer a large part of England, causing King Aethelred and his witch to flee to Normandy.

Annus horribilis – 1014 turned out to be a comfortless year. First, Father died in January. I had enjoyed a reunion with him for less than a twelvemonth, but it was enough to set me on my path of destiny since I learnt so much from him. His decease left me bereft and mournful. On 3 February, King Sweyn, at the height of his power, passed away. He had nominated his son Knut to succeed him and while the lords of Lindsey accepted him as their King, much of England did not. Disgracefully, the Witenagemot met and invited Aethelred and his second wife, Queen Emma, home from exile. It seems they did not want an inexperienced and foreign youth as ruler of England. Imposing conditions of just, respectful behaviour on Aethelred, they gathered an army and marched to Lindsey to oust the Danish fleet.

I had become fast friends with Knut. I had only twelve winters behind me, while he must have been eight years older. Owing to the effects of Ronain's harsh discipline, the age difference did not much show. Still, I admired Knut. As we were both strapping youngsters, my eyes were on a level with his. He was large in stature and very powerful, fair, and distinguished for his good looks. His nose was thin, prominent and aquiline; his hair was profuse, his eyes bright and fierce. We must have sensed our joint path in those early days – it is the only way I can explain our instant mutual friendship. It solidified around the close and successive deaths of our parents and it was this relationship that would lead to my future clashes with the witch.

This, the season of deaths, moulded my life; during those early weeks of 1014, the Aetheling Æthelstan died of wounds inflicted fighting the Danes. He made his will on the day of his passing and it contained many provisions. The one that involved me was the bequest of the Cumtun estates to me as my father's eldest son. Oh, the joy! Restoration by princely act of my childhood lands of high heathland, wooded weald and the worn sward of ancient droveways snaking along the chalk ridges. In short, the priceless emerald gem they had snatched away from me. Whether it was a deed inspired by conscience or politics, I will never know, but I never forget to pray for his soul at this time of year.

Æthelstan was a curious man. I feel sure that, had he lived, he would have made a better king than his father, but he would have had to reckon with his stepmother, Emma. Æthelstan was a warrior prince and by the time of his death, he had accumulated a large collection of swords, precious war horses and combat equipment. In his will, he left his brother, Edmund Ironside, his most prized possession, a sword which had once belonged to King Offa of Mercia.

I still think, magnificent as was this bequest, the silver-hilted sword he left me, also of Frankish manufacture, bettered it – not in lavishness but in balance. I cannot be sure of this, unless, one day, I have the chance to wield Edmund's, but it is a sensation of mine. What a wonderful gift! Brought to me on the day of the Aetheling's funeral by a messenger with tidings of the Cumtun inheritance. How can I describe my emotions? The weapon my cousin gave me still has a special place in my heart, but it cannot match the splendid, rune-engraved blade Æthelstan bequeathed me – fit for a king. It would become my constant companion, lethal and loyal.

The speed of the English attack took us by surprise and Knut was nowhere near the great leader he was to become. He upped anchor and led his fleet away from Gainsborough in ignominious flight, deserting the Lindsey lords and leaving them to their terrible fate.

The first test of our friendship came some days later when we landed in Kent. There, Knut ordered the English hostages entrusted to Sweyn to be set ashore. I had seen their wrists and ankles bound and watched them disembarked across the broad shoulders of the Vikings. What could it portend, I wondered?

This is a breach of honour!

Did Knut read my thoughts and doubt me? Would this explain why, with wild folly in his eyes for what he saw as a Saxon betrayal of his rightful claim, he chose to pass me his battle-axe? Why me, otherwise? Likely because I am a Saxon and he wished to test the extent of my loyalty. He selected a hostage, the son of a mighty ealdorman and ordered his bound hands to be placed on a log.

“Take off his hands!” he commanded me, disguising the petulance in his voice with a cough.

I wanted to argue and reason with him but, at twelve, I already possessed the wisdom born of self-interest to guide me. I could not afford to offend my new and powerful friend.

“Lord, lord, spare me! I beg you! I need my hands!”

The merciless Vikings laughed and mocked the wretch. Ignoring the pitiful pleas and wailing of our victim, a lad a little younger than me, with a ferocious swing of the whetted axe, I lopped off the hands at the wrists. One unforgiving blow sliced through both rope and sinews. Knut laughed and slapped me on the back.

“It was well done, Godwine, my friend!” Wrenching the axe from my shaking hands, he didn't pause for breath but ordered the blinding of two other hostages and similar mutilation and maiming of yet more.

Thankfully, I was not called upon to enact these atrocities. In my immature mind, these acts were not so atrocious, but rather the actions of a young man determined to exact revenge and incur respect. In short, he had my full support. Neither, at the time, did I question his abandonment of the Lindsey Danes. Later, I saw it for what it was – a terrible act of disloyalty. I was also smart enough to realise the end it achieved served its purpose, and sufficiently wise to keep my own counsel.

* * *

We sailed from Sandwich to Denmark, the first time I had crossed the sea. I had evidently passed Knut's test of loyalty for I was honoured and excited to spend the voyage in the bows of the leading longship, standing next to him. We were as brothers: he took me into his confidence in spite of my tender years. Thus, with misgivings, I deduced his intention to wring co-operation from his brother, Harald, by claiming joint sovereignty over Denmark.

I knew he could not be dissuaded, but I still wanted to express my doubts. “Is it not a hazardous venture, Sire?” I ventured.

“This, my dear Godwine, is but an idle threat. With it, I mean to extort a fleet of ships from my brother to regain England.”

“But you must bargain, Lord,” I suggested timidly.

At which, he bellowed a laugh and said, “Smart fellow! Of course, I'll offer to renounce my claims to the Danish throne.”

Knut loved the game of chess and I believe he saw international affairs as a similar game of strategic moves and countermoves.

We sailed upriver into an estuary whose name I learnt and promptly forgot, then marched some leagues overland to the court at Heidaby on the Baltic coast. This route, Knut told me, saved many miles of sailing around the long peninsula and into notoriously difficult seas. King Harald received us with a show of affection, gifts and feasting. For the first time, I had an inkling of the opportunities that were opening before me. What was to stop me, the intimate confidant of the claimant to the English throne? I sensed I could be the important lord I had dreamt of becoming ever since my father lost his Sussex estates, now restored. Observing the mood swings of Harold from warm welcome to smouldering resentment of Knut's claims, I also learnt about the dangers of dealing with volatile monarchs.

Knut was in complete control, although he appeared to outrage his brother and risk being sent packing out of Denmark. Here were the first signs of a great king. Skilfully playing his sibling like a hefty fish on a delicate line, he got what he wanted – a large number of warships and men in exchange for renouncing a claim he never truly intended to pursue. As soon as the spring weather set fair, we would sail for my homeland, send Aethelred into exile once more and install Knut on the English throne.

I grew excited at the prospect of my best friend becoming King of England. What might it mean for me? My fervid imagination could neither foresee nor match what was to become reality.

Chapter 3

Bosham, Sussex, 1017 AD

Surely a man should base his antipathies on actual experience? In the case of Queen Emma, I confess aversion arose at a distance out of sympathy for another. During the brief presence of Sweyn Forkbeard in England, his son, Knut, met a beauty from Mercia and fell in love with her on the instant. The lady, a young noblewoman from Northampton named Aelfgifu, was equally smitten. Fatefully, they married by performing the hand-clasping ceremony, as was Danish custom – a pagan rite. Later, she bore him two sons in quick succession.

I flatter myself that I was Knut's closest friend and confidant. I am, therefore, in a position to state without doubt that he never stopped loving his wife. After Aethelred's death in April 1016, the royal council in London – the Witenagemot – elected Edmund, known as the Ironside, and Emma's stepson, as King. Edmund, so different from his father, was a warrior I admired. His death, from wounds inflicted in a battle against us, saddened me deeply.

In the autumn, the Ironside met with Knut on an island near Derehurst to negotiate peace terms. Emma, ambitious for her eldest son, must have been disappointed at the agreement that was thrashed out. All England north of the Thames was to be Knut's domain, while Edmund would keep the south, including London. The realm would pass to the other man if one died. In November, Edmund succumbed to his wounds and left the crown to Knut, whose coronation took place in January.

After this event, my acquaintance with Aelfgifu began. I had heard so much about her beauty, patience and charm from Knut that I longed to meet her. Before we met, Knut took me aside and revealed his predicament.

“The Church will never accept Aelfgifu as my Queen, my friend. She is not a Christian and our wedding was sealed with the Norse hand-fasting rite. They tell me that my Council will declare that I must marry a baptised wife and abandon Aelfgifu. What am I to do, Godwine?”

He seethed with rage, but how could he defy them all and maintain his throne? I wrestled with this problem but could not bring forth advice before he blurted, “I will never cast aside Aelfgifu, Godwine. She will not be shut away in a nunnery – discarded like an old shoe!”

“What? Will you defy the Witan, my King? Is it wise?”

“I will not set aside the kingdom won by the strength of our sinews for this nonsense.”

Of that, I had no doubt, else why had Knut ordered the overseas murder of Aethelred's other son, Eadwig? Emma was our prisoner at this stage, but only because she chose not to flee to Normandy, where she had wisely sent her sons, Edward and Alfred, for safety. Knut had met with her – a courtesy visit to the former Queen of England. On his return, I witnessed his earlier resolve waver and dissolve.

“She is fair of face, Godwine, and a woman of rare intelligence. Poor wretch, she spent years with a man a score of winters her elder. What a cold match it must have been!”

I gazed at him in horror.

“You do not mean to reverse the situation?”

“I am only ten years her junior.”

“Then you are serious? But what about Aelfgifu?”

“Think of the advantages, my friend. At one stroke, I pacify the Witan and I present myself as an English king by wedding her – and a Christian one, to boot! No support for her Norman sons from Emma's family will be forthcoming. The Vikings will no longer use Normandy as a base to attack our land. All told, it would be a feat of political astuteness! Do you not concur?”

What could I say? I looked at his keen eyes and nodded. I knew him well enough to fear crossing him. Above all, I recognised the advantages of such a move.

“But what of Aelfgifu?”

“Ah, that's where your role is crucial.”

Strange thoughts flashed through my mind which maybe he read, for he laughed and hastened to explain.

“As I said, I will not set her aside. I have made plans for my wife. Your estates are in Sussex, are they not?”

“At Cumtun.” Where was this leading him?

“It is well. I find I possess lands in my gift at Bosham, in the same county. My advisers tell me but three leagues separate the two places.”

“It is so.”

“Then I will make them over to Aelfgifu. From Cumtun, you will keep a watchful eye over her.”

I bowed my assent, but as I did, my heart sank. Was I to be isolated to guard a woman – however important – when I had other ambitions for my future?

“Some things you know nought of, Godwine.”

My curiosity aroused, I scrutinised his thoughtful face.

“Aelfgifu hates Emma and this loathing began with the murder of her father and the blinding of her brother. It happened before we met, and occurred before her terrified eyes. Aethelred ordered the deed, but only after Emma convinced him to revoke the pardon he had in mind for Ealdorman Aelfhelm. The commander carrying out the act was a Norman, named Hugh – no wonder my wife hates that race.”

“And now you –” I bit my tongue in my haste not to finish the thought.

“Will marry her enemy? You grasp the gist.”

The situation was more complicated than Knut realised. That I saw, even as an inexperienced youth, before thinking it through in the fullness of time. The one thing on his mind was the danger Emma posed to Aelfgifu and any children she might bear him. It would have been so much easier to repudiate her, but his love was too enduring. At that moment, I cursed my ill-luck, believing myself condemned to a life of reclusion, a hermit in the Sussex countryside, however mellow and apple-scented the surroundings.

There can be little doubt which of the two women suffered the greatest shock after the wedding. I believe Emma expected Knut to cast Aelfgifu quietly aside soon after their marriage, but he showed no willingness to do so. From then on, the two women became unforgiving rivals. I know of the distress afflicting Aelfgifu, because Knut commanded me to escort her to Bosham at the end of June.

The sweetness and vulnerability of the lady stole my heart during that first meeting. I would lie if I denied her comeliness. She had a perfectly oval-shaped face, crowned by long, golden tresses framing beguiling violet-blue eyes. Her nose was straight and narrow, her lips as red and soft as a robin's breast. I swore to myself I would never let anyone harm her. Anyone? My King excluded, of course! The mental torment he had wreaked on Aelfgifu by his wedding to Emma was indescribable. Her dignified conduct on the journey to Bosham in the knowledge her husband was making marriage vows to her hated foe, could not have been more admirable.

Two women, two competitors, one so unlike the other: Emma, comely, dark-haired, vindictive and Norman; Aelfgifu, winsome and blonde, sweet-natured and Saxon. In common, they were beautiful and both fiercely protective of those they loved. Another difference; Aelfgifu had a personal hold over Knut that Emma never did. The witch, however, gained rapid influence with the King. They wed on July 2 and, breaking with Saxon tradition, she ensured she was crowned beside him at their wedding, six months after his own coronation. This was the first time a queen had been bestowed this honour. On this occasion, she extracted an oath from Knut that any son they had would be Knut's heir in preference over any child born to Aelfgifu by him. The witch had cast her spells.

Showing the sweet lady around her homestead at Bosham, I revelled in her limpet-like friendship. It was as if she knew from the first, by instinct, that she would need my support one day. There were moments when I dwelt on the future, praying I would not become a woodland recluse, much as I loved the Sussex sward. A life of inactivity was inconceivable – I was not one for sitting around idly.

I do not know whether Knut suggested to Aelfgifu that she ought to confide in me before we departed. Whatever, her hospitality, even on a difficult first day in her new surroundings, was such that she installed a relationship of mutual trust as we consumed mead and honey cake. I prefer salted food but, willing to please her, I partook of the sweet delicacy with hearty endeavour.

“Lord Godwine, may I ever count on your friendship?” she asked, her violet-blue eyes brimming with tears.

“Lady, were you not the wife of my dearest friend and sovereign, I would give you even my soul.”

“One of his wives,” she said, her natural sweetness embittered for the first time.

“Nay, Lady, affairs of kingship! His heart belongs to one only.”

Her grateful smile as a tear rolled down her cheek made me want to take her in my arms to offer comfort, but it is perilous to embrace a queen.

“I fear for my life, Godwine.” The words were uttered so quietly and tremulously that I could barely make them out.

“No harm will come to you while there is breath in my body, I swear this to you, here and now.”

I am proud to say that this is an oath I managed to uphold.

“Oh, would that it were so! Do you think Knut will leave me alone in Bosham? Of course,” she said hastily, maybe aware of my origins, “there are worse places.” She stared around and made a brave effort, but her sigh was worth a hundred words of lamentation.

“He will spend some days with his…” I hesitated, wishing to spare her, “… consort,” I chose the word with care, “for the sake of appearances. He cannot afford to offend the Church and the Normans. What Knut does is for political necessity, not out of love.”

“Do you really believe that, Lord Godwine?”

“I do,” I said, with heartfelt conviction.

She raised her glass. “To a long and true friendship.”

She smiled and, like the sun, her smile lit up my being.

With time, it proved to be an auspicious toast. I did not suspect that day, as I departed for nearby Cumtun, how fateful this new amity would be.

Chapter 4

Cumtun, Sussex, 1017 AD

The misconception that I had been condemned to a life away from the King lasted less than two months. I soon learnt his forays to Bosham, but three leagues away, under an hour by horse, would become frequent and intense. They would also include consultations with me, his friend and counsellor. I flatter myself that his preference was for an hour with me over the same time with the entire Witan.

On this first visit, he confided in me that he had ordered Uhtred, the Ealdorman of Northumbria, to come to him with a guarantee of safe-conduct; all along, he planned to have him killed.

“You see, Godwine, Uhtred grew too mighty when he wed Aethelred's daughter. You know, he fought against us at Assandun. After our great victory, he fomented unrest in Northumbria, north of the Tees, whilst to the south of the river, the people remain loyal to me. In other words, a traitor!

Hence, I sent for him to discuss peace terms, but we did not talk. Instead, I had my faithful thegn, Thurbrand, hide behind a curtain spread across the width of the hall. Had you been there, Godwine, how amazed you'd have been! He and his men sprang out in mail shirts to slaughter the Ealdorman and forty of his chief men who entered with him. What better way to start my reign?”