17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

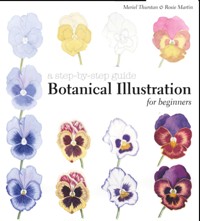

A unique and exciting approach to botanical illustration, this beginner guide demonstrates everything you need to know about capturing beautiful botanical specimens on paper. Each exercise guides the reader through a different aspect of botanical illustration, breaking the whole process down into simple, easy-to-follow stages. Whether you are a beginner looking for advice on composition and how to plot out your initial drawings, an experienced artist looking to develop your skills at colour mixing and working with unusual colours, or an old hand looking to capture more challenging and complex textures and shapes, there is something for botanical artists of all levels. Acclaimed artists Rosie Martin and Meriel Thurstan ran the popular botanical painting course at the Eden Project and have filled this fantastically illustrated guide with practical and inspirational worksheets, colour swatches, sketches and stunning finished paintings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 171

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Botanical Illustration for Beginners

A Step-by-Step Guide

.

Botanical Illustration for Beginners

A Step-by-Step Guide

Meriel Thurstan Rosie Martin

.

Contents

Introduction

Materials and equipment

Techniques

Colour

Drawing

Basic botany

Painting

Pattern and texture

Coloured pencils

Composition

Working with white and black

Complex forms

Suppliers and useful addresses

The illustrators

Index

Glossary

This bisection of a tulip captures its exotic colours as well as its structure.

.

Introduction

Learning botanical illustration from scratch can be a daunting prospect, so we have tried to simplify matters. Together with examples and explanations, we have set out step-by-step exercises for you to follow, with notes on how to tackle each project. Most are quite simple; others are moderately easy and a few are more challenging.

This book will give you basic and vital information on drawing, colour recognition and mixing, how to lay watercolour washes, understanding and applying watercolour, coloured-pencil techniques, and how to superimpose one colour over another for depth and vibrancy. These are the building blocks of botanical painting.

We also discuss aspects of botanical illustration that you may find more demanding: pattern and texture, composition, complex forms, painting white flowers (without using white paint) and how to paint black flowers and berries.

As botanical illustration can be enjoyed from both an aesthetic and scientific perspective, there is also information on botany and the accepted use of Latin when naming plants.

With time and practice, you should become a competent and proficient artist, able to tackle any botanical subject with confidence. For those with some experience already, remember that however successful you may become, you never cease to learn.

Rosie and Meriel

.

The trooping crumble cap fungus, or fairies’ bonnets (Coprinus disseminatus syn. Psathyrella disseminata) turns into a viscous black liquid after a few hours, so has to be painted quickly.

.

Early botanical art

The earliest known depictions of indigenous plants were carved into rock in c.1450 BC to adorn the walls of the Great Temple of Tuthmosis III at Karnak, Egypt. Of the 275 plants shown, not all are identifiable, but they are a timeless record of ‘all plants that grow … in God’s Land, which were found when his majesty proceeded to subdue all the countries …’, as the inscription declares.

.

The Middle Ages

Medieval monks drew on vellum or parchment using a goose feather quill and ink made out of oak galls. Provided that the artwork was kept safe from predatory bugs and mildew, it survived to inform and give pleasure to many future generations.

Once the printing press had been invented in the mid-fifteenth century, artwork was available to many more people; but once again, these prints had to be suitably preserved in dry, shaded conditions if they were to last for any length of time.

.

The Vienna Dioscurides is an early 6th century illuminated manuscript of De Materia Medica, the Greek Herbal of Dioscorides. This page from the antique scientific text shows the earliest representation of the Orange Carrot, at the time considered a medicinal plant.

.

Seventeenth century onwards

Artists who used oil-based paints on canvas, like the Dutch flower painters of the seventeenth century, ensured that their work would survive for centuries, if not forever.

Now, in the twenty-first century, we benefit from the expertise of generations of artists and scientists, and can make sure that we have the best possible materials to hand for our work.

.

The seventeenth-century painting Still Life of Flowers by Dutch artist Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-84).

Materials and equipment

Naturally, today’s botanical artists want their work to last, so choice of materials is an important consideration. A workman is only as good as his tools, and poor tools will make for substandard work. It can be tempting to economize by buying low-quality paint, paper and brushes, but your work will suffer, so buy the finest that you can afford.

By mixing your own colours from a limited palette, you can create all the many colours found in nature.

.

Watercolour paints

Research on the manufacture of watercolour paints and their durability has really taken off in the last few decades. Some colours are known to be fugitive, but modern manufacturers’ colour charts have notes on the lightfastness of each paint, so we can make properly informed decisions.

• Initially, keep to a limited palette, but be sure to buy artist’s-quality paints. They are a bit more expensive than the student’s-quality range, but they last longer, the colours are better because they contain more pigment and they are worth every penny.

• Watercolour paints come in pans, half pans or tubes. If you opt for pans or half pans, take an empty paintbox and fill it with your choice of colours. If you use tubes, squeeze a small amount on to the palette. If you don’t use it all, allow it to dry for next time. It is easily reconstituted with water. Tubes can sometimes be difficult to open. Hold the cap in hot water for a few seconds to loosen.

• Occasionally, you may need white for small hairs or bloom. Add to your paintbox some Chinese white, titanium white or white gouache.

• Learn to mix your own colours from your limited palette.

• In particular, learn to mix greens, the botanical artist’s most frequently used colour.

.

Coloured pencils are a good medium for the dry leafy bracts and nuts of the hazel.

.

Learn to mix greens. Green is the colour that causes most problems for the beginner.

.

Pencils

Pencils are sold singly or in boxed sets. You will find it useful to have a range of pencils from 4H (hard) to 2B (soft). Anything softer than 2B tends to leave loose graphite on the paper, which can spread and dull the image when you begin to paint. (If you do end up with loose graphite on your drawing, try gently rolling a ‘sausage’ of white tack across it to pick up the surplus.)

Some artists prefer to use refillable clutch pencils, which have the advantage of never changing length and so retain balance in the hand. Leads are available in different grades and thicknesses.

Sharpening your pencils

It is important to keep pencils sharp at all times, so use a pencil sharpener or very sharp craft knife. To get a particularly sharp tip, try using wet-and-dry abrasive paper (about 400 to 500 grit size) or a fine emery board, gently twisting and rubbing the lead in a rolling action across the surface. Wipe off the surplus graphite with a tissue. A truly sharp pencil should hurt when pressed into your fingertip!

.

Coloured pencils

You may be happier with coloured pencils than with a paintbrush. There are so many colours available that you could end up with a glorious rainbow of hues from which to choose. Alternatively, opt for a basic palette of, say, a dozen colours to mix and blend in the same way as watercolours (more on coloured pencils).

.

This magnolia seed head was worked in coloured pencils over watercolour on HP Fabriano Artistico 300 gsm (extra-white).

.

Brushes

Nowadays we can choose from a wide range of brushes, from the relatively expensive to the more economical synthetic ones. The best brushes for botanical painting are sable, noted for their ability to hold a good quantity of paint, to form a point and to spring back into shape.

Some brushes on the market are specific to certain types of painting. Sable brushes are high-quality, multipurpose brushes, suitable for both beginners and professionals.

Keep the amount of materials you buy to a minimum. Two brushes are sufficient to start with: a size 4 and a size 1. But they should be top-quality sable (round, not miniature). It is a good idea to have a fairly large (size 6) synthetic brush for mixing colours, keeping your better brushes for painting.

At the shop, ask for a container of clean water and wet the brush. If the hairs don’t form a good point, don’t buy the brush. If buying from a catalogue, online or by mail order, you can ask for a replacement if a brush is faulty.

Never leave brushes standing in the water pot. Store brushes with their handle downwards in a pot or jar, in a custom-made brush case, or rolled in corrugated paper once dry.

Cut lengths of plastic drinking straws to protect the tips of the brushes. If the hairs of a brush become unruly, gently mould them with your fingers and some softened soap and leave to dry. Make sure all the soap has been washed out before use.

.

This is a good example of using watercolour initially, with extensive use of coloured pencils laid on top.

.

Supplementary equipment

In addition to paints, pencils and brushes, you will need:

• A hard white or kneadable eraser.

• An eraser in the form of a pencil, which can be sharpened to a point. This is good for intricate work. Or cut off a corner of a hard white eraser on the diagonal to achieve a sharp point.

• A large, clean feather or cosmetic brush to sweep eraser detritus from the paper.

• Two water containers: one to wash your brush, the other for mixing with paint.

• Corrugated cardboard makes an ideal brush case. Lay the brushes in the grooves, roll up and secure with an elastic band.

• A paint rag or absorbent kitchen paper.

• A sheet of cheap paper or acetate to place over the parts you are not working on, to protect the drawing or painting from the natural oils on your skin. Acetate is also useful for gridding up.

• A mixing palette or a large white china plate.

• Low-tack masking tape, for which you will find many uses.

• A way of holding a specimen in place. Model-makers’ suppliers sell an inexpensive contraption called a third arm, which has moveable arms and clips. Some have a magnifying glass built in, which is very useful. Or use a bottle filled with water or sand, a plastic milk container with the top cut off, a bulldog clip, paper clips and corks, Oasis, or florists’ lead spikes. Be inventive!

• A loosely filled bag of rice to prop up solid objects.

.

You will find a range of different graphite pencils useful for detailed drawings.

.

The following items are not essential, but you may find them useful:

• Masking fluid, available bottled or in a dispenser with a nib.

• A quill or drawing pen with which to apply masking fluid.

• A magnifying glass.

• An adjustable table easel or a drawing board with books or a brick to raise it 7.5–10cm (3–4in) to ensure that your line of sight is approximately at right angles to your work.

• A ruler.

• A pair of dividers or callipers to check size and proportions.

• A microscope for studying really small parts.

• A digital camera, computer and printer-scanner for recording details, resizing a subject and to record your finished work, or to present your artwork as prints or greetings cards.

.

Stamens can be masked out with masking fluid, which is then removed and the fine details added.

.

Paper

Archival papers, made especially for watercolourists, are sustainably sourced and acid-free, allowing paintings to endure for a good hundred years or more.

Use HP (hot-pressed) paper or Not (cold-pressed) paper. Not paper has a slightly rougher surface that lends itself to some subjects, such as rough-skinned vegetables. HP paper is more sympathetic to very fine details such as stamens and fine hairs.

Try different makes of paper until you find one that suits you. Don’t forget to try the reverse side as well – there is usually a subtle difference. The ‘right’ side has the watermark or manufacturer’s impress and is usually smoother.

Some papers are whiter than others. Your choice may be dictated by your subject and preference.

Paper is supplied as single sheets, pads or blocks. If you buy single sheets it is usually possible to have them cut by the supplier into halves or quarters.

In addition you will need some cheap semi-opaque layout paper for initial drawings, some tracing paper and cartridge paper for drawing (which does not take watercolour well).

.

Vellum

If you are confident about using watercolour paints on paper, you might like to try using vellum. Vellum is made from calfskin or goatskin and is a traditional surface chosen by calligraphers and many botanical artists. It is not cheap, but it has a luminous quality that makes paintings glow. The best type for botanical painting is marketed as Kelmscott vellum. It is available in a range of sizes, ready prepared for painting.

The main characteristic of vellum is that it has a non-porous surface and the paint is liable to lift off if you are building up colours and tones in layers. So endeavour to paint each area with the correct colour and tone at the outset, painting extremely ‘dry’ and using the stippling technique. Washes are not appropriate, apart from a very pale initial wash if you feel you need one.

Before starting to paint, tape the vellum to a piece of white card or a white board. Lightly rub the surface with fine-grade pumice powder, a mixture of pumice powder and French chalk, or the very finest sandpaper, in order to remove any grease. Your supplier will be able to give you advice on this.

.

Using watercolour on vellum

Can I rub out initial pencil marks?

Yes, using a fine eraser – either a pencil eraser or a sliver of a hard white eraser. Keep pencil marks to a minimum, using a fairly hard pencil (2H) very lightly.

.

Can I lift off colour once it is dry?

Yes. Simply lift off with a damp brush or flood with clean water and blot with absorbent paper.

.

Can I put on more than one layer?

Yes. Allow the first layer to dry thoroughly, then add more colour with an almost dry brush and small, stippling strokes. Further layers are possible, with care.

.

How easy is it to add fine details?

Easy, as long as you use an almost dry brush and small, stippling strokes, as above. The white hairs on the generic leaf shown above were painted with white gouache straight from the tube.

.

Using coloured pencils on vellum

The examples above show how tones can be built up slowly with coloured pencils. From left to right, the test piece shows:

1 Initial layer – very light pressure.

2 Further layer, leaving out the area where the light falls.

3 The same stage, but now burnished with a blender pencil.

4 More dark tone added on the shaded side.

5 Highlight lifted out with a fine eraser, more dark tone added, and a final burnishing.

.

Comparison of vellum and watercolour paper

These four little pictures of a grape hyacinth (Muscari latifolium) give an idea of the different appearance achieved according to the support and the medium used.

These two illustrations are both on vellum. The left-hand one is in watercolour; the right-hand one uses coloured pencils. The vellum support has a creamy appearance.

See Complex Forms, for an exercise in painting a grape hyacinth on vellum.

The same grape hyacinth is also shown painted on paper (Fabriano Artistico extra-white). The left-hand one is in watercolour; the right-hand one uses coloured pencils. Notice how much whiter the background appears in both these paintings.

Techniques

There are many building blocks for good botanical illustration, so refer to the notes below as you work on your chosen subject.

A right-handed artist usually has the light source on the left.

.

How do I make sure my drawing is accurate?

• Before you even pick up a pencil, study your subject.

• Carry out some research if you have any doubts about it.

• Make sure you have a perfect specimen.

• Look carefully at all the small details, using a magnifying glass or microscope if necessary.

• Count the stamens and other multiple parts. It is better to spend time on this at the outset, because structural mistakes are not easy to correct later.

• Make a list of adjectives that describe the different parts of the plant. Are they woolly? Smooth? Hard? Prickly? Rough? Papery? Shiny? If you have a hard, shiny subject and it appears in your drawing to be woolly or rough, you are doing something wrong. Refer to your list of adjectives constantly to make sure that you are on the right track.

• Use the method for structural drawing.

.

How do I transfer my drawing to watercolour paper?

There are several ways to transfer your composition onto watercolour paper.

• Scribble over the reverse with a soft graphite pencil and trace through. This is not recommended as you can get a fine layer of graphite left on the white watercolour paper, which could then make your colours muddy.

• Tape the sketch to a window pane, tape the watercolour paper over the top and trace through, using a 2H pencil very lightly so as not to score lines in the paper.

• Use a light box in the same way as described above.

You may have to draw lightly over the traced lines to sharpen them. Keep your initial sketches near you while you paint, to remind you of any foreshortening or other quirks. Make notes on the preliminary drawing of the angle of your light source, colours and a few adjectives to describe your subject.

.

How do I make something larger – or smaller?

One simple way to scale up a drawing is to draw a grid over it in pencil. If you don’t want to mark the drawing, draw the grid on a sheet of acetate laid over it. Use a fine-tipped indelible marker pen on the acetate.

Take a piece of layout paper and draw a second grid of the size that you want the subject to be, then copy the original, square by square. In the example of the strawberry (shown here), you can see how each square has been drawn separately but still relates to the overall composition of the subject. (If you wish to scale something down, do the same exercise but using a second smaller grid.)

.

Exercise: Faded anemones (Anemone coronaria ‘De Caen’)

These past-their-best anemones were painted at a large scale with a limited palette of colours, plus violet. A camera, computer and magnifying glass will make the task easier.

Step 1

Measure the flowers carefully. A digital camera and computer will help you to see how they would look when enlarged.

.

Step 2

Position the two flower heads on the page. Use masking fluid to mask out some of the stamens so you don’t have to work around them when painting the petals. Block in the petals with initial wet-into-wet washes.

.

Step 3

Add detail with further washes or stippling with an almost-dry brush. Check the structure of the flower centres using a magnifying glass.

.

Step 4

You can leave the stems until last, and use a mix of the various colours. At this stage you could add some loose stamens to give the picture movement and reflect the dying nature of the flowers.

.

How do I paint a wash?

All washes need practice, and it is worth spending time with some scraps of watercolour paper to make sure that you know what you are doing. See overleaf for more details.

.

.

Wet-on-dry wash

This is a wash painted on dry paper. It needs to be of an even depth of colour. Take care with all washes that you keep within drawn lines.

1 Place the paper on a board resting on a block so that it is tilted towards you.

2 Mix up a good amount of the chosen colour, keeping it very wet.

3 Using a suitable size of brush for the area to be covered, load it with paint.

4 Starting at the top, make sure that there is a good reservoir of paint and pull this down gently until you have covered the whole area.

Don’t go back and forth over the same area – let the brush flirt with the paper, touching each part just once.

Use just the tip of the brush. This will ensure that the paint runs straight from the point of the brush on to the paper.

If there is surplus paint at the bottom, gently lift it off with the tip of an almost-dry brush.