4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

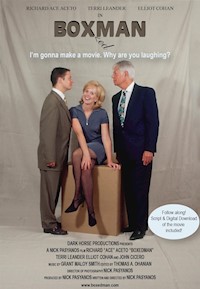

"BoxedMan - I'm gonna make a movie, why are you laughing?" is the story of Nicholas Pasyanos's declaration, commitment and eventual completion of this improbably farfetched journey.

The Walter Mitty that lives in us all taunts us throughout our lives to do something out of reach, and it is oh-so tempting. Nicholas succumbed to the siren call and jumped into the deep end of the pool, with the expectation he would learn to swim in the process.

This journey could be attributed to mid-life crisis, dreamer thinking or insanity onset; take your pick. Nicholas heard all of these theories as he shared his desire with friends. With the help of divine grace, countless blessings, mini-miracles, inexplicable random occurrences, and the aid of an Academy Award winning editor, his film was completed.

Then, the reality struck of entering countless film festivals, acceptance to some, and rejections from most, which is how it goes. But hey, how many people can claim an official rejection letter from the Cannes Film Festival?

Beyond the self-deprecating, casual narrative, BoxedMan is an entertaining, inspirational and informative story of the journey that is making a movie.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

BOXEDMAN

I'm Going To Make A Movie, Why Are You Laughing?

NICHOLAS PASYANOS

Copyright (C) 2021 Nicholas Pasyanos

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by India Hammond

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

Please use the following qr-code online to learn more and to watch the movie:

Contents

Forward

1. How It Started

2. Jim Cameron And Stephen Spielberg Come To Town

3. Help In Casting

4. First Day Of Shooting

5. Ace Is Back

6. Porn Shop Shoot

7. The Antagonist Is Ready

8. The Nose Picker Is Found

9. Life Imitates Art Or Vice Versa

10. Drinking Beers At 10 Am

11. Billie Price Being Billie Price

12. Snow In Summer

13. A Frustrating Night Scene

14. I Break My Friend’s Car Window

15. The Bottling Plant

16. Bjs, Limos, And Cops

17. My Movie Comes To Life As Titanic Sails Into History

18. Ten Degree Beach Day

19. Theater Reshoot And Clean Up

20. Four Months Of Editing

21. A Composer That Gets It

22. Post Master Sound

23. Film Festival Debut

24. Close But No Cigar

25. The Screenplay

Images

About the Author

Forward

FIRST TIME FILM MAKERS ODYSSEY

So, you want to know what it’s like to make your first movie when you have no formal training or experience? This is a good place to start. Best of all, you’ll experience it from the perspective of someone who didn’t create a “Blair Witch” phenomenon, but a typical, truly independent film that got lost in the sea of other films seeking a distributor or home of some sort.

It was truly a Herculean effort both physically and financially to shoot on film and edit digitally. At the time, one out of every twenty films landed a home. Mine was not one of them. Since then, the rise of digital film making, editing, and web access has made this opportunity easier and cheaper than ever to execute. If you have a voice in your head saying, “I think I can make a movie and hopefully get discovered,” don’t ignore it. Living with regrets is something I highly recommend avoiding.

There are many successful film makers that have written “How-To Books,” which could influence you to think, “Hey, I can do that too.” The reality is much like what happens in any casino, there are a few big winners and a lot more losers. This book will enlighten you to the challenges and realities of making a feature length film on the cheap. I attempted to show all sides of the experience so that you can appreciate what lies ahead. If, after you read this, your inner muse is still saying go, I’d say go. In the chapters to follow, I will attempt to clearly delineate my thoughts, whether philosophical, opinion, fact, absolute fact, superstition, or neurotic self-doubt. In this way, you can get the most from my experience.

Best of luck.

How It Started

I’M GONNA MAKE A MOVIE! I announced with great trepidation to the circle of casual friends gathered around me in the cockpit of my sailboat. Possibly a nanosecond passed before my friend, Ron, broke out laughing so hard I thought he might suffer internal injuries. Ron, you see, is a well-grounded, self-made entrepreneur who owns successful businesses in several states. Constant travel between businesses, homes, and worldwide vacations, keeps him and his wife in perpetual motion. Ron has what many would consider an enviable life.

The occasion was our annual get together sail with Ron and his wife Sandy, another couple of Ron’s friends, and my girlfriend Carol, who sat silently observing this exchange. Carol, knowing of my commitment to the project, was the only one not laughing at what the others saw as my apparent loss of mind. She was also the only one to know that I was quickly becoming a best customer of Border’s, Barnes & Noble, and independent bookstores everywhere. I was consuming filmmaking books at a book a week pace. This was my approach to an ambitious, self-paced, educational process to ready myself to make the film.

Ron proceeded to fire questions at me, questions that were unavoidably important to a businessman evaluating a project. His questions were sensible. 1) Will you be taking time off from work? 2) Do you have adequate financing? 3) Do you have experienced help?

My answers were 1) “NO,” I can’t leave my job, because I need the money. 2) “NO,” I have to personally fund the project because it would be too hard a sell, to find investors, given the circumstances. 3) “NO” again, because I don’t know anyone that has any film making experience. This was why I’d given myself a year to educate and prepare for the film I’d planned to start shooting in the summer of 1997. The year would also allow me time to purchase all the equipment, find shooting locations, and cast the film. I saw no point in going into the overwhelming fact that I had 60 shooting locations and 43 speaking roles to fill. Why offer up ammunition to be shot with?

The more I tried explaining myself to this logical businessman, the further I got from convincing him how serious I was. He was thinking that if this was a business venture, he didn’t feel good about it. Futility prevailed, I threw in the towel, and shut up. Ron’s continued chuckling over the next couple hours as we plied the waves fortified my resolve and convinced me not to talk about my project to any thinking, sane, person again.

First off, I need to relate some personal history so that you can try to understand my apparent insanity and passion. I have always been a film buff. I have had a love affair with movies my entire life. From adolescence, I had seen way more movies than any of my friends. I was born in Boston, and my family lived two blocks from Fenway Park for the first seven years of my life. After my first seven years, we moved every couple of years, but not more than a few miles from the former residence.

Today, we have multiplexes that have most of the current releases playing under one roof. Back then, in the 50’s and 60’s, theaters only exhibited a double feature. The main movie was coupled with asecond, lesser film, kind of like an A side and a B side on an old 45 RPM vinyl record, if you’re old enough to get that reference (if not, Google/Wikipedia). You had to search the newspapers to find the movie you wanted to see and hope it was nearby. Between downtown Boston and the immediate suburbs, there were countless theaters with an impressive range available to us. On Washington Street, in downtown Boston, there was the Paramount, the RKO, and Cinerama. All of them were very large venues by today’s standard.

Cinerama is a format that, due to its production and exhibition costs, is extinct and will never be seen again. Cinerama was unique because the screen was narrow, top to bottom, and proportionately very long, left to right, 90 feet long to be exact. The fact that the screen was very long, and had a curve in it, filling your peripheral vision, created the feel that you were immersed in the image. Today that aspect ratio would be stated as 2:55 to 1 or could be as wide as 2:78 to 1. Most films today are shot 1:85 to 1, or 2:35 to 1. The narrow and long image was possible because movies made for Cinerama was shot with a specially built camera with three lenses shooting left, center, and right. The three cameras filmed every scene simultaneously. When the film was projected in the theater, they used three projectors with the same spacing. The projected images overlapped in a seamless fashion, creating this panoramic view. Beautiful to look at, but all costs are now more than tripled. Is it any surprise that when Hollywood hit cost conscious times, Cinerama disappeared? Fortunately, several of the movies that I saw there are out in DVD now. Check them out and see just how wide they are. Some of the titles are: It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Beyond the 12 Mile Reef, How the West Was Won, Grand Prix, and The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm.

One other theater worth mentioning still exists: the Brattle Cinema in Harvard Square. It was and still is an art house theater, although at the time I wasn’t aware of that distinction, nor, frankly, would I have known what that meant. It was where I saw subtitled foreign films and little-known movies, like Lord of the Flies, which didn’t play at the other theaters. Although my sister and I had exposure to a diverse range of movies, as with most kids, we preferred standard popcorn matinee fare.

Every summer we got a mega-dose of movies because of my father’s occupation. A chef in Boston restaurants, my father took a sabbatical every summer to run restaurants on Cape Cod. That transplanted our family for the entire summer to a number of seaside towns. My sister Irene (who is four years younger than I) and I were in the same boat. We didn’t know the local kids, so we became sole companions to each other. The local movie theaters became our other companion. The theaters in these communities changed movies every two-to-three days, probably because they were attempting to get viewers to visit twice if they were on a one-week vacation. Guess who got to see every movie that was released those summers? Right! And we didn’t even miss the ones that didn’t interest us. We no doubt became their best customers, but I’m not so sure they appreciated our patronage. My sister and I, coming from a family in the restaurant business, were very adventurous eaters. We used to bring our own munchies to the theater. Odd things like pistachio nuts, canned sardines, and canned anchovies. Only now can I imagine the cleaning crew at the end of the night discovering pistachio nut shells and empty tins of olive oil under the seats we sat in. No one ever confronted us, probably because we were some of their best patrons. Those were memorable summers, for both us and the theater owners. But the biggest reason we saw so many movies during the rest of the year was because my mother used the theaters as our babysitter. Our mother would take us to the theater, get us seated, armed with hours’ worth of eats. She would return later to pick us up after she’d finished her errands or shopping. (This was back when child abduction wasn’t a concern.)

As I mentioned earlier, all shows included two films that alternated continuously. Sometimes we wouldn’t get to see the second film in its entirety and other times we got to see both movies once or twice. The repeat viewing was when I would get the opportunity to dissect the film. I was studying the structure and assembly of the movie subconsciously. Little did I know it but that was the start of my filmmaking education; an education that I wouldn’t put into action until over thirty years later. During those years, I graduated high school, got married, got divorced, and worked for a living (CliffsNotes version). Basically, life got in the way, and frequent visits to the theater wasn’t part of it. During those years, most of my movie viewing was on network TV’s movie of the week. Movies would be shown on TV only after several years had passed from their release date, and you’d have to endure what felt like endless commercial breaks. A two-hour movie would be broken up with an hour of commercials. It was considered an EVENT when a movie was shown within a year and a half of its theatrical release date. An amusing far cry from today’s video, cable, satellite services, and streaming that offer vast content within months of their theatrical release. Without a doubt, the most significant development in my life of movie viewing had to be the advent of the home video formats of videotape and laserdiscs. Sometime in the mid 80’s, VCR machine prices dropped to an affordable level, and video rental shops started opening all over town. As America adopted the new technology, I resumed my voracious pursuit of movie viewing. Video afforded me the opportunity to get caught up on all the movies I had missed. It was only natural for me to start collecting video cassettes of my favorite films. I collected video cassettes for approximately six years until I discovered the next best thing. The laserdisc.

My introduction to the laserdisc came by way of a plug from the then Siskel and Ebert movie review TV show. The format had been around for close to a decade, but was not mainstream. It was the format that only serious movie buffs and filmmakers watched and collected. Siskel and Ebert were both laserdisc collectors, which basically turned me into one. The advantages of the format were a sharper picture, more accurate color, and correct framing (widescreen vs. the compromised full screen format that broadcast TV and video cassettes had).

The best part of all was the alternate audio track that contained the director’s commentary. This is a feature that is very common on today’s DVDs but was an exclusive perk on some laserdiscs. I purchased almost all the discs that had director’s commentary tracks. I clearly got the filmmaking bug listening to them. The creative process of filmmaking really appealed to me. At that point in time, I had been a part-time portrait and wedding photographer for over 25 years. Photography and filmmaking were so closely related that I began to question the career paths I had taken in my life. I was now a 45-year-old, middle-aged guy with regrets and some deep-rooted questions emerging. Is what I’m feeling genuine regret, or some male menopause, mid-life crisis? My gut tells me it’s regret.

Jim Cameron And Stephen Spielberg Come To Town

In the winter of 1994, Jim Cameron (director) was shooting the opening scenes of his film True Lies in Newport, RI, at Salve Regina College. I live only three miles from the campus.

Jim Cameron was one of my favorite directors, having made The Abyss, Aliens, Terminator, and Terminator 2. After True Lies, he made Titanic in 1997, which to this day is the second biggest box office hit in history, due to his Avatar taking the number one spot. Jim’s coming to town to direct a movie with Arnold Schwarzenegger was all I needed to know.

Fortunately, my uncle Duke was the assistant deputy of security at the school. I asked if I could come and observe the filming.

“That would be difficult,” he answered. “But I have to hire a lot of people for security. I could get you a job in security for the eight days of filming. You can watch while on duty and get paid for it.”

Well, if that didn’t turn out to be the best part-time job of my life. For me, an aspiring filmmaker, it was Fantasy Camp. My work assignment was to prevent others from getting close to the filming. Strangely, there was a net of Newport Police officers outside our perimeter that prevented anyone from reaching us. So here I was securing nothing, watching a major motion picture being made by a famous director, eating free food along with the rest of the production staff, while earning $12 an hour doing it. I’m now understanding why major films cost so much to make.

No complaints from me. I was stationed very close to almost all the primary filming. I got to look over Jim Cameron’s shoulders as he directed most of what is now the opening eight minutes of the movie. All the filming took place on freezing cold nights in February. The location was supposed to be in the Swiss Alps in winter, and it sure looked the part. John Bruno (the visual effects supervisor) took the images of Salve Regina’s mansion administration building and digitally composited it into the images he had taken of the Alps. That winter was a severe one with snow falling every few days. In spite of Mother Nature’s cooperating with the intended scenario, Jim Cameron still felt it necessary to bring in a snow making truck to dress up the natural snow. This had something to do with the color of the snow. Clearly, nature knows nothing about color balance and realism. The snow making truck pretty much absorbed all the capacity of the Newport Ice Company. Tons of ice was delivered and fed into the snowmaking truck as fast as the deliveries were made, round the clock. The man-made snow was used for ground cover. All the windowsills of the mansion were adorned with a white, pad-like material wired on to assimilate snow on the sills. All this was installed with a rented cherry picker.

I’m not convinced that the average moviegoer would pick up on these details, but they sure didn’t escape the attention of Jim Cameron, arguably the most detail-focused director in the industry. I was so excited to be a part of this whole thing that I was willing to make the personal compromises in my life. As the scenes in the movie took place at night, I had to do an eight day with little sleep marathon. I couldn’t take time off from work, so I was working my day job and then showing up to work the night shift on the set. Getting very little sleep for eight straight days was never an issue given this incredible opportunity. I was too pumped up to get tired.

My True Lies experience was all the inspiration I needed. Then and there I knew that I had to find a way into the industry. The most accessible way, both logistically and expediently, was screenwriting. Screenwriting was the most logical entry point because it is the foundation upon which all movies stand. I would pursue this challenge fully aware of the odds of my ever getting anyone in Hollywood to read whatever it was I was going to write. Damning the odds, I forged ahead and purchased several books on screenwriting.

The first script I wrote after absorbing the basics was Armageddon. Not theArmageddon but my Armageddon. It is best described as a script that starts out as a conventional doomsday drama and ends with a science fiction/theological twist. I was so confident in my ability to pitch its marketability that it now permanently resides in my closet.

It’s said that you should write about what you know, so the second script I wrote was BOXedMAN, the story of an insecure corrugated box salesman working for the boss from hell as he attempts to succeed in a business climate made up of either ambivalent or eccentric characters. Drawing upon countless selling situations I’ve encountered, the people involved, and combining a dose of humor from my comedic personality, made the script a natural to write.

The protagonist was an underdog guy, like me, who enters a business because he thinks he can make a lot of money, like me, looking for love, like me, working for a psycho, like me, and navigating a world of interesting characters…like me. My real-life job situation was consuming my subconscious to the point of fueling my writing. I was frustratingly employed as a sales rep by one of the world’s largest box companies. The company was in financial trouble for several years, being helmed by a megalomaniac, with a staff of yes-men lackeys. They, as a group, drove the sales force, of which I was a part of, to the brink of servile resignation. The demands put on all sales reps coupled with the impossible situations they created between us and our customers were close to unbearable. We were beat, mentally, with no relief in sight.

Combine this impossible situation with the hopelessness that comes when working for a huge corporation and you can see the genesis of Scott Adams’ Dilbert cartoon. If you don’t work for a large corporation, read a couple Dilberts in your Sunday paper and I need not say more. As bad as all this sounds, I’ve got one more layer of frosting for this cake. The general manager, my immediate boss at my plant location, was not a nice guy. Many of my coworkers had the same opinion. We saw him as moody, mean spirited, and distrusting. Aside from that, I guess he was a good manager.

Living and working day after day in this environment was extremely hard. I started sleeping with a mouth guard which prevented me from waking in the morning with a mouth full of ivory dust. While I may have been keeping all this inside, emotionally, it was all imbedding itself in my subconscious and ultimately into my spec script. I could not, not write about this. Yet, while I was in the process of writing the script, it never occurred to me once that this was a cathartic, therapeutic experience. I knew consciously that my boss was going to be the antagonist in this story, but I failed to recognize that this was also a way for me to deal with his oppressive ways. So, my boss became the model for the antagonist in my film, which made me the natural model for the protagonist. Makes total sense, right?

The only other ingredient to this brew that would become a screenplay was the inspiration of two relatable films. Working Girl and Tin Men were both films about business, love, and bad bosses. I studied them and tried to capture some of their strong points.

BOXedMAN had taken over a year to write, including subsequent drafts. I learned later that nothing is ever final. You still make changes throughout rehearsals and actual filming. Call it perpetual evolution. All in all it was now completed and I was ready to start pitching it to whoever would listen. A trip to the bookstores resulted in a stack of books listing how to pitch, along with directories of agents, producers, and studios. But before I would send my first letter or make my first call, two consecutive events altered my track.

One night, I watched a video by another one of the successful new filmmakers of the 90’s. I watched Edward Burn’s first film effort Brothers McMullen. I was impressed and inspired by this well-made, small budget film. It had won best picture honors at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah the year before. My attraction to it increased after reading all the buzz surrounding it. Edward shot this film using his mother’s home, borrowed apartments, and guerrilla style shooting in public places, which would avoid the hassle and expense of getting permits from municipalities. He shot it with a handful of actors and friends over seven months of weekends. He personally funded the project to the tune of $25,000. You see where I’m going here. I’m making connections. I’m starting to head down the slope without being sure I want to. The final push down the slope came the next morning.

I finished reading the last chapter in Robert Rodriguez book, Rebel Without a Crew. Robert is another one of the new filmmakers who broke out in the 90’s. He made a low budget or should I say micro budget feature for $7,000 entitled El Mariachi. The extraordinary thing about El Mariachi is that it is an action film. Just about an impossibility when viewed through the prism of conventional wisdom. The other interesting fact surrounding this film was that he wrote the script while living in a test lab that he volunteered to be in for thirty days, which earned him $3,000, about half the film’s production cost. You can’t make this stuff up. Robert went on to be a studio player and write his memoirs, Rebel Without a Crew. The last chapter is entitled “10 Minute Film School,” in which he advocates taking the bull by the horns and making your film as he had done. Be ‘self-sufficient’ and be scary as he oversimplifies the immense task. I buy this pitch, hook, line, and sinker as I follow my ambitions blindly.

The wheels start to turn. I am a portrait photographer. I can light a scene. I have good credit and low debt. I could buy a used camera, lights, and the film needed. My mind is crunching the possibilities. I have a script. I weigh that my story is similar to Brothers McMullen in the fact that there aren’t any costly effects. That was made for $25,000. El Mariachi was made for $7,000. Bang! Fusion! Brothers McMullen and El Mariachi in a combustible reaction, yielding a moment of clarity for me. Some might think it was a moment of madness.

“I’m going to make my film BOXedMAN.”

Do I have any other options? Sure, I can pitch my script to a bunch of people who won’t take my calls.

“I’m definitely going to make BOXedMAN.”

I hurriedly called Carol to tell her about my out-of-left-field decision. There’s silence at her end as she absorbs what I just said. Having read the script, she’s trying to envision what I’m saying.

“There are so many characters. There are so many locations. What, Where, Who, Why, How?” She continued firing off the most immediate obstacles she could think of. There are a lot of them.

“I’ll figure it out,” I countered. As I spend a good portion of my workday driving around visiting customers, I suspect she thinks I just drove off the highway into a bridge abutment. I tell her I’m okay and that I’m going to start planning for my production. Okay, she answers. I think she’s humoring me.

That evening, I started my serious relationship with every bookstore in a 100 mile radius. Beginning then and for the next year, I’d pop into bookstores during my daily business travels and peruse the racks for new titles. I’d look for any books that I hadn’t seen before, but thought would be beneficial. My focus was on any book that would simulate a film school curriculum. I needed to buy books on every aspect of filmmaking because I knew nothing. Filmmaking is a collaborative art where a group of experts band together for a period of time to produce a finished product. My job was to learn as much as I could about that group and abbreviate it into a smaller crew with as little compromise as possible.

The books I purchased were on directing, sound recording, set design, cinematography, editing, and musical scoring. It was clear that I needed to be adequately familiar with all aspects of production before starting. I read and attempted to learn from several books I purchased on the subject of film directors. The books were enlightening, but in many respects were either anecdotal or delved deeply into the philosophies of the filmmakers. You would have had a need to know these detailed bits of information to appreciate the narrative. I was seeking meat and potatoes information, not esoteric, conceptual ideals. The books on basic directing were of greater overall value to me. They were to the point, without the artiness. I thought hard about what director’s movies would be closest to mine and I came up with a cross between Woody Allen and the Farrelly brothers.

Two years later, and two weeks before my finished film was to debut, the Farrelly’s, There’s Something About Mary was released nationally. I went to see it on opening day and was totally startled to count eleven common thread gags in both movies. Was my writing and sense of humor that similar to the Farrellys? Interestingly, Bobby and Peter Farrelly grew up about thirty miles from me. From what I’d seen and read about them, I knew we shared a similar sense of humor. To experience it in that way was almost surrealistic. Maybe it’s some kind of Rhode Island, geographic thing.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, so back to the books on directors. There was a lot written about the psychological interactions between the director and his cast. These areas were of particular interest to me. Being a sales rep I’ve always been aware of the psychology of relating to people. No relation means no common understanding.

A director’s interaction with his cast is an extremely important dynamic that cannot be understated. I cannot imagine succeeding without it. A director’s successful interaction with his cast only increases the chances that you’ll both come out winners.

The books on cinematography were equally helpful in that they educated me in establishing the proper camera angles to appropriately convey what is going on in the scene. In addition to the camera angles, I learned the value of using the appropriate establishing shots for the scene to be shot. The master shot is wide, establishing the locations. The medium and close up shots are used to properly capture and accentuate what is being said in a scene. The most important dialogue necessitates the tightest composition. These are things that we as movie viewers are probably subliminally aware of, but it was good to read it and know for sure. The cinematography books also went into how to light a scene, and thankfully, my twenty-five years of experience as a part-time photographer allowed me to shortcut those chapters. My scan through those pages confirmed that I already knew this stuff. Although I appreciated the individual styles of cinematographers, I needed to use an approach that would be easy to maintain throughout this lengthy shoot.

I adopted a straight-forward style, using primarily flat lighting for all my interior scenes. My rationale was that most offices are lit with fluorescent, which are flat to begin with. I chose my lighting equipment sources to be compatible with the flat fluorescent, which I needed. Flat lighting would allow me to set up my lights and then move my subjects around as need be, without having to move the lights again.

This would be a major time saver when changing camera angles. Decisions like this one allowed me to film a lot more per day than if I had to move lights to create consistent light patterns viewed from different angles.

I would later regret that I didn’t absorb the nuances of sound recording that were spelled out in the sound recording books. The book went into miking techniques in various situations, recording levels, and potential problems. The potential problem section was the one I’d wished I paid more attention to. You will read in Chapter 11 what I’m talking about. The scene I’m referring to was shot in a diner. My thirteen year old nephew, the sound recorder, and I, the default, resident expert, failed to notice the low drone of the central air conditioning system, which layered in with the dialogue spoken in the diner. The microphone was set up over the table between the speaking actors, just below the cursed air conditioning duct that was contaminating my recording. When we got to the post sound work at the end of the shooting, my sound editors told me that it would cost hundreds of dollars of corrections to improve, but not eliminate the drone. I agreed to pay for the attempted fix. It was improved, but you will notice upon reviewing that there is an unnatural ambient sound that “pulls you out of the scene” as the industry terms this affliction. A costly lesson attributed to on the job training.

The book I purchased on set design was one that I only scanned, primarily for basic familiarity. I made the decision not to get too involved, recognizing that without a budget and a dedicated set designer, it would be impossible to address this area properly. Being concerned with color schemes and décor of locations to complement what is happening or being said was way too much to contemplate when you know you’ll be understaffed. However, it was good to know the basic rules of design so that I would avoid a blatant faux pas that would draw attention to my inexperience. I would have to rate the books I read on editing as extremely helpful in my shooting. There were countless examples and explanations of how scenes could or should be filmed, so that when they are assembled chronologically later, the visual flow would be smooth and as seamless as possible. That’s as far as I read on the subject because I knew I would read the remaining detailed part of actual editing when the time came at the end of the shooting. No point in studying something I won’t use for almost a year away. I’d only forget what I read by then and I didn’t want to clutter my mind with any more info that I was already absorbing.

I did get one book on musical scoring but the subject was so far down on my need to know list that I gave it a scan and lumped it in with the editing book’s back burner status. I assumed that I would be doing the editing myself via VCRs as Robert Rodriguez did. The musical score would totally be at the mercy of whoever would help me. I love music, but its writing is a total mystery to me. I have a tough time playing a kazoo in tune, just so you know where I’m coming from. As you can see, I was boning up and prepping to the max on actual production related subjects, yet I was taking a real leap of faith and a deferred attitude on post-production related matters. It was partially irresponsible in a way, but I also couldn’t worry about everything or I would never get started.

Eventually, I amassed a library of books. By the time I found myself reading redundant information, I knew I was ready.

Help In Casting

Where to start? A sense of being overwhelmed set in as I attempted to prioritize pre-production. As confident as you need to be to undertake a first film, there’s still that underlying doubt that’s ever present. The inner voice that asks, “Can I really do this?” or “Am I biting off more than I can chew?”

I determined that the easiest task at hand would be the identification of locations for the shoot. I reasoned that getting through that part would ease me into the most major stage of all, casting. Baby stepping my way into this cave of uncertainty was to be my approach. “A journey of a thousand miles starts with the first step” and all those metaphors from years of watching “Kung Fu” on TV all came back to me. I went through the entire script and notated the locations required (answer: 60). I amusingly observed that if I wrote the script knowing that I’d be shooting it myself, I would have had the entire story take place in my living room. I would also have written the story with a total cast of two, maybe three people. The headcount for BOXedMAN is 43. Another big number. I’ll worry about casting after I deal with location hunting.

Having written my script before deciding to actually shoot it was a problem. I wrote it to be a funny script, without any regard to production considerations. Now I was gonna pay. I had to find every single location. A movie theater, several restaurants, diners, a nursing home, outdoor shopping centers, a barber shop, exteriors both night and day, just to name a sampling. You get the picture. I was in way over my head. Fortunately, my day job gave me a huge leg up on scouting office locations. When I’d see a location that met with my pre-visualized needs, I’d ask the customer or prospect if I could film there. I would explain that I couldn’t pay them rent, but would acknowledge them in the credits of the film. It was amazing to find that no one turned me down. People I don’t even know didn’t turn me down. It reaffirmed my faith in people. Most will do good given the chance.

When I spoke to filmmakers from New York and Los Angeles I got a different story. They have to pay for all locations along with permits and insurance to cover any possible eventualities. This is enough proof to encourage independent filmmakers to shoot in smaller cities. Smaller cities don’t view filmmaking as an interruption that warrants compensation. I wouldn’t have been able to afford to shoot 60 locations if I had to pay for them.

I went through the entire script and started listing locations both interior and exterior. Now I really had a handle on what was ahead. One hundred and forty scenes spread over sixty locations. I told myself I couldn’t dwell on the enormity of the project because I might have come to my senses and bailed out before I began. I used the analogy of climbing a mountain. If you look at the whole thing, you wouldn’t want to climb it. Dealing with it ten feet at a time isn’t as mind crippling and hopefully before you know it, you’re half way up. That’s what I kept telling myself.

All my spare time was consumed with location scouting and reading books to prepare for the shoot. My large laserdisc movie collection was another source of researchable help in planning my scenes out. Many times, I’d read a scene in my script and remember a film I’d seen with a scene that might resemble it. Even a remote resemblance could lead to resolving a “how-to” question. This practice allowed me to storyboard in my mind and resolve questions of execution.

Years later, I read that Jim Cameron used the same practice when shooting Titanic. He was indecisive on how to open the film. His answer came after viewing the opening scenes of approximately seventy laserdiscs accompanied by a bottle of tequila. I’m not sure how much influence the tequila had, but referencing other people’s work is clearly a creative catalyst.

Director’s commentary tracks on laserdiscs were another big aid in planning. A party scene in my film had to have spoken dialogue in the midst of a party with music and ambient crowd noise simultaneously. (See Chapter 5, Sunday Sept 21.) How do I do this? Well, the answer is on the Mrs. Doubtfire collector’s laser disc set. Chris Columbus, the director, explains that in a scene involving a children’s party, he faced the same dilemma. His solution, which became mine, is that the background people in the scene move their lips silently as if they’re talking. You just add the ambient background music and background dialogue in post-production. So when you’re filming the scene, you only have the speaking actor’s dialogue to record. Very cool tricks of the trade. By the time January ‘97 came around, I was feeling very prepared.

Coinciding with my preparatory planning was the local excitement generated by Stephen Spielberg’s setting up shop in Newport for his film Amistad. Spielberg was turning Washington Square back 150 years. All signs of the present day…lamp poles, telephone wires, parking meters and sidewalks…received cosmetic treatment or temporary removal. The streets were filled with dirt to the heights of the sidewalks disguising the curbs. An entire building, “the jail house,” was erected in St. Anne’s Square. The stone-faced building was made of fiberglass panels over a wood framed shell so realistically that it looked real even up close. Their shooting schedule was approximately one month in duration, shooting from early morning until mid-evening. I intended to try to watch shooting both before I went to work in the morning and after work at night. I even went so far as to submit photos of myself at a casting call in hopes of getting first-hand experience.

Although I didn’t get cast, I did get to shake Stephen Spielberg’s hand on the first week of production. I was hoping that something spiritual might pass through the handshake and give me good luck. Watching Spielberg work was both inspirational and a diversion from my personal pressing schedule. I had to get going on equipment buying.

I called several used camera stores listed in American Cinematographer Magazine. I narrowed down the choice of cameras to three after comparing prices and features. The cameras I considered were all built in the mid to late 60’s, back in the days before video replaced film as the evening news medium. The evolution to video orphaned thousands of 16mm movie cameras. They’re all available now for prices ranging from $4000 to $8000. A lot of money for a thirty year old camera but a lot less than a present day $100,000 new 16mm camera. The new cameras have time codes and many bells and whistles that an old camera lacks, but when you’re a know nothing neophyte, you can’t miss something you don’t know exists. The only considerations I had were handhold ability and crystal sync motor. The crystal sync motor keeps the camera shooting at 24 frames per second without variation; an important feature as professional DAT recorders (sound), and eventually digital recorders, also have quartz crystal timing devices in them that keeps them recording at non-varying timing. If either your camera or sound recorders were to vary the slightest amount, you’d be faced with people’s voices not aligning with their lip movement.

Robert Rodriquez explained that that’s what he dealt with while shooting his $7000 El Mariachi. Robert used a non-sync camera (imperfect timing) and a Radio Shack portable cassette recorder (imperfect timing). With two imperfect devices in hand, you are, in effect, creating infinite variables of deviation. He had to sync his footage one line at a time using visual means rather than the accepted method of using a slate.

A scene is slated not only for identification, but for lining up the motion picture image with the sound recorder. The editor in post-production indexes the frame where the upper slate makes contact with the lower slate. He then indexes the sound recorder to where the sound of the ‘bang’ is heard. He then runs the film and sound together throughout the entire scene to sync them together. So much easier than Robert’s method. Robert did it his way because that’s the only equipment he had at his disposal for his no budget film. Seeing as I wasn’t trying to break the record he established for a feature film under $7000, I decided to spend more money up front for a crystal sync camera and a DAT recorder. Recognizing that I was about to bite off way more than I could chew, I felt I would rather run up a little more debt and keep my aggravation quotient down. My hair was and is grey enough, I didn’t want it to turn shock white.

After discussing my project with several camera shops on both coasts, I decided to do business with Du-All camera in New York City. George Gal and his sons Steve and Jeff run the shop. George Gal turned out to be a renowned camera repairman who had authored books on 16mm cameras and their operation. He is one of three people in the world who services the ECLAIR line of cameras, a now out-of-business French camera manufacturer. He offers in-house service and, bearing in mind I was acquiring a 30-year-old camera, it was an important consideration. The deal clincher was Du-All’s one-year warrantee. This is not a typo, ONE YEAR. All other stores offered 30-90 days. This definitely brought peace of mind considering that a production schedule like mine would be approximately six months in length.

Keeping the surprise factor to a minimum was always underlining all my decisions. Having never handled a motion picture camera before, I felt it important to line up my visit to Du-All for a day when all three cameras were in stock for my consideration. I kept contact with George weekly, surveying his ever-changing used inventory. In late March ‘97, I called and he had just taken in a trade completing a full house. All three different cameras under one roof! I asked him to hold off selling any of them till I came in to see them the next day.

What I thought would be an hour visit turned into a four hour shopping trip. It took an hour to get the feel of the Éclair, the Cinema Products CP16, and the Arriflex 16 BL, as well as learning how differently the film loaded between brands. Talk about give and take considerations. The camera that loaded the easiest felt the worst when your shoulder mounted it. The camera that shoulder mounted the most comfortably had the highest price. It took another three hours to weigh all considerations and finally decide on the Arriflex 16 BL. It was the most expensive of the three but a decision I never regretted. As I proudly cashed out with a $6500 purchase, a young man and his girlfriend came in with a check for $25,000 for a newer than mine, used Arriflex camera. I’m not a filmmaker for two minutes and I’m already feeling peer pressure envy. Life’s unfair. Something always seems to happen to dampen your spirits just when you’re feeling good. Leaving the store in Manhattan, I quickly forgot my envy, as I walked down 42nd St. proudly carrying my new camera in its case.

The entire next day, my mind raced with questions regarding the use of my camera. Juggling these thoughts with the everyday tasks and demands of my sales job was enough to occupy my conscious and sub-conscious mind. Enough so that when I stopped by my office at the end of the day, I hadn’t noticed the light on my phone, indicating a recorded voice mail message. Voice mail was just installed and I was unfamiliar with its use. I finally retrieved the message several days later, when I became aware that there was a message. The message was from the AMISTAD casting office. The message was: Please call tonight for further instructions. You have been cast in tomorrow’s shoot (this was now two days after the message was left). I quickly called the casting office, but of course it was too late. The scene had already been shot and they were now on the last day of shooting. If I had it in me to cause self-inflicted injury, I’d be dead now. That oversight caused me to beat myself up mentally for an entire month.

With the camera purchase now behind me, it was time to concentrate on the sound recorder (DAT). I checked mail order houses for pricing and determined that the portable SONY TCD D10 PRO II was the model to buy, but the price was in the $4000 range. My calls to L.A. used dealers found prices in the $2500 range, which was still more than I wanted to spend. A few weeks later, success! A music shop in New London, CT, had an ad in a local music industry paper that led me to call, finding they had a used Sony DAT recorder for $1300.

I couldn’t drive there fast enough to purchase it. This is the kind of purchase that was perfect timing. As I write this, I still can’t believe I found that deal, just when I needed it. One more piece of equipment down, and several more to go.

The next months of prep was spent on the phone with several mail order photo supply shops in N.Y. investigating and purchasing light stands, tripods, lights, scrims, reflectors, etc. Every night after work, questions and answers and decisions had to be made, not to mention money spent. As April went quickly by, the hanging question about casting was most definitely on my mind. I have a cast of 43 actors to assemble and I’ve got to learn where to find them, how to audition them, how to weed them out, and then rehearse and direct them.

I reference my laser disc of Brothers McMullen. The writer, director, and actor Edward Burns has a commentary track on which he explains how he put his cast together. He took out an ad in a Long Island newspaper advertising his need for non-paid actors. He surprisingly received 1500 replies. That alone gave me a comforting feeling. The thing that concerned me the most about that approach is getting people responding that couldn’t act and maybe have never performed before. I certainly didn’t have the time to weed through a large number of respondents, so in April, I contacted the largest performing arts group in Providence, RI. Trinity Repertory Theater, which had a renowned apprenticeship program. Unfortunately, I learned that they are Equity or SAG members, which meant that they could only work for pay. I explained my predicament and was told that there are provisions and exceptions, but you have to put up a $1000 bond and some contractual considerations. The money and the paperwork was another hurdle that I didn’t need. Abandoning that approach led me to plan B. Plan B was contacting a number of dinner theater playhouses in Rhode Island.

One of these was in my town, The Newport Playhouse and Cabaret Restaurant. It was run by Jonathan Perry and his uncle, Matt Siravo. I had watched a few of their well-performed, entertaining comedies and identified some actors I could easily and gladly use.

But a visit to City Nights Dinner Theater in Pawtucket, RI, was the most pivotal event that would ultimately affect the quality of my cast.

The theater director Ernie Medeiros was sympathetic to my pitch. I explained to Ernie that I was a neophyte that needed some pointers in casting. He invited me and anyone from my crew to attend a two-day audition for an upcoming play. It would be my first exposure to the backstage of any performing arts productions.

Not only would I learn how an audition is conducted but I could also scope out his prospects for my own productions. This is too good! I thought. I gathered up several of my crew members to attend the audition with me. Watching the process not only taught me how to conduct my own, but allowed me the opportunity to find several actors for my film. I approached them individually during lulls in the action, told them of my movie, and got a phone number. After two consecutive nights of auditions, I felt pretty comfortable with my observations. I actually developed a feel for the process and am pleased and surprised that I formed opinions about the auditions. I have identified approximately 10 actors that I can use for my audition. 43 roles is what I have to fill. I was still way short. I told Ernie this as I started to fret. He extended an offer for me to come in another time and peruse his extensive file of headshots amassed over a decade. Another blessing!

Days later, I returned to spend over four hours pulling close to two hundred headshots from a plastic filing bin. This was a virtual treasure trove of head shots leading to potential possibilities and answered prayers. Ernie spent time going over the photos, telling me the experience and talent level of my choices. He created a huge shortcut for me. We collectively narrowed the list down to approximately one hundred actors. I took down their names and phone numbers, thanking Ernie for simplifying my life.

Now that I had casting partially under control, I thought it time to turn to the ugliest aspect of independent filmmaking—MONEY. One thing I knew for sure is that I didn’t have enough of it. And I didn’t want to take out a home equity loan. Coppola did it for Apocalypse Now, but I’m not him and I’m not making Apocalypse Now. As I mentioned, hunting down investors to back a filmmaker with zero experience was too unsavory a task. I could just imagine the strange looks I’d have gotten and just knew it wasn’t an option. Facing a bank loan officer with a similar pitch was equally unsettling. So, I resigned myself to the most popular form of financing known to filmmakers, the credit card. I applied for a pile of them all offering low introductory rates. The two biggest expenses I would face regularly would be film and processing, so I opened accounts with Eastman Kodak and Du-Art Labs. In my talks with Du-Art, the question came up as to how I would edit my film. I told them I was planning on using two VCR’s and a used JVC video editor I had recently purchased for this purpose. That’s how Robert Rodriguez did El Mariachi, I told them. Silence at the other end. Then a pearl of wisdom.

“It’s very difficult that way,” said my guiding voice on the phone.

I explained that I was highly motivated to get my film made and would deal with the difficulty. They advised that when they processed the film, I should order the videocassettes with time codes and key codes burned on the copies, just in the event I might come to my senses and have the film edited on an Avid digital system.

I confessed that I didn’t have the money for a professional edit, but would consider their advice. “I’ll let you know when I send in my first rolls of film for processing.”

After hanging up, I remembered that the film critic of the Providence Journal Michael Janousonis interviewed a Rhode Islander two years before who had received two Academy Awards and two Emmy Awards for co-founding Avid Corp. and their groundbreaking digital editing system. I had saved the article for future reference (God knows why). The time of reference was now. I called information to track Tom Ohanian down in hopes he could give me advice on this seemingly troublesome aspect of film production.

I got Tom on the telephone and was pleasantly surprised by his accessibility. I anticipated less. Our first call lasted for 45 minutes spanning movies we enjoyed—our tastes, likes, and dislikes. Tom realized how determined I was to make my film. He asked if I could send the script to him. I told him I would and he said he would call me after reading it.

Several weeks later he called to tell me he had read it on a red eye flight from L.A and couldn’t stop laughing. He woke many fellow passengers as he laughed out loud. Tom told me that if I shot it like I wrote it, I would have a funny picture and he wanted to be a part of it. He wanted to edit my picture, he informed me, and that I would have a miserable experience trying to do it myself with VCRs. Attempting to synchronize the moving lips on the screen of the VCR with the recorded dialogue on DAT tape would be insanely time consuming. I reiterated that I was on an anemic budget and couldn’t possibly afford it. He insisted on doing it and told me, “I’ll give you a price you won’t refuse.”