Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

If you have an inner life, you inevitably have a double life. It remained to be seen which of the two lives would gobble up the other.Brice and Emma had bought their new home in the countryside together. And then Emma disappeared. Now, as he awaits her return, Brice busies himself with DIY and walks around the village. He gradually comes to know his new neighbours including Blanche, an enigmatic woman in white, who has lived on her own in the big house by the graveyard since the death of her father, to whom Brice bears a curious resemblance . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 163

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Pascal Garnier:

‘The combination of sudden violence, surreal touches and bone-dry humour has led to Garnier’s work being compared with the films of Tarantino and the Coen brothers, but perhaps more apposite would be the thrillers of Claude Chabrol, a filmmaker who could make the ordinary seethe with menace. When the denouement suddenly begins in The Panda Theory, it is so unexpected that I read the page twice in shocked disbelief. This might be classed as a genre novel, but Garnier’s take on the frailty of life has a bracing originality.’ Sunday Times

‘A small but perfectly formed piece of darkest noir fiction told in spare, mordant prose … Recounted with disconcerting matter‑of-factness, this marvellously unpredictable story is surreal and horrific in equal measure.’ The Guardian

‘A dark, richly odd and disconcerting world … devastating and brilliant.’ Sunday Times

‘The final descent into violence is worthy of J. G. Ballard.’ The Independent

‘This often bleak, often funny and never predictable narrative is written in a precise style; Garnier chooses to decorate his text with philosophical musings rather than description. He does, however, combine a sense of the surreal with a ruthless wit, and this lightens the mood as he condemns his characters to the kind of miserable existence you might find in a Cormac McCarthy novel.’ The Observer

‘For those with a taste for Georges Simenon or Patricia Highsmith, Garnier’s recently translated oeuvre will strike a chord … While this is an undeniably steely work … occasional outbreaks of dark humour suddenly pierce the clouds of encroaching existential gloom.’The Independent

‘A brilliant exercise in grim and gripping irony.’Sunday Telegraph

‘A master of the surreal noir thriller – Luis Buñuel meets Georges Simenon.’ TLS

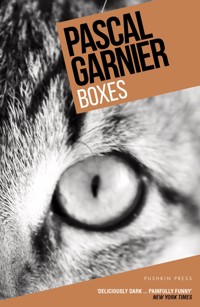

Boxes

Pascal Garnier

Translated from the French by Melanie Florence

Contents

FOR LAURENCE

Brice sat on a metal trunk he had struggled to close, with a silly little rhyme going round and round in his head: ‘An old man lived in a cardboard box / With a squirrel, a mouse and a little red fox.’ Cardboard boxes: he was completely surrounded by them, in piles stretching from floor to ceiling, so that in order to go from one room to another it was necessary to turn sideways on, like in an Egyptian wall painting. That said, there was no longer any reason to go into another room since, boxes aside, they were all as empty as the fridge and the household drawers. He was the sole survivor of the natural disaster that at one time or another strikes us all, known as moving house.

Following a terrible night’s sleep in a room which had already ceased to be his, he had stripped the bed of its sheets, quilt and pillows, and stuffed it all into a big checked plastic bag he had set aside the night before. He had a quick wash, taking care not to spray toothpaste on the mirror, and dutifully inspected the place in case he had forgotten something. But no, apart from a piece of string about a metre and a half long which he unthinkingly wound round his hand, there was nothing left but the holes made by nails and screws which had held up picture frames or shelves. For a brief moment he thought of hanging himself with the piece of string but gave up the idea. The situation was painful enough already.

There was still a good hour before Breton Removals would come to put an end to ten years of a life so perfect that it seemed it would last for ever.

That cold November morning he was furious with Emma for having left him helpless and alone, in the hands of the removal men, who in an hour’s time would descend like a swarm of locusts to ransack the apartment. Both strategically and psychologically, his position was untenable, so he decided to go out for a coffee while he waited for the world to end.

The neighbourhood seemed already to have forgotten him. He saw no one he knew, with the result that, instead of going to his usual bistro, he chose one he had never set foot in before. Above the bar, a host of notices informed the clientele that the telephone was reserved for customers, the use of mobiles was strongly discouraged, it would be wise to beware of the dog and, of course, no credit would be given. A guy with dyed red-blond hair came in, issuing a general ‘Hi!’ He was some sort of actor or comedian Brice had seen on TV. For a good few minutes he tried unsuccessfully to remember his name, then since this quest – as annoying as it was futile – led nowhere, he persuaded himself he had never known it. Behind him, wafts of disinfectant and urine came from the toilet doorway, mingling with the smell of coffee and dead ashtrays. A sort of black tide made his stomach heave at the first mouthful of espresso. He sent a few coins spinning on to the bar and made his escape, a bent figure with turned-up collar.

In the stairway he passed Monsieur Pérez, his upstairs neighbour.

‘Today’s the day, then?’

‘Yes, I’m just waiting for the removal men.’

‘It’ll seem strange for you, living in the countryside.’

‘A little, no doubt, to begin with.’

‘And particularly in your situation. Speaking of which, still no news of your lady?’

‘I’m hopeful.’

‘That’s good. I’m very partial to the countryside, but only for holidays, otherwise I don’t half get bored. Well, each to his own. Right then, good luck, and keep your chin up for the move. It’s just something you have to get through.’

‘Have a good day, Monsieur Pérez.’

For the past month Brice had felt like someone with a serious illness. Everyone talked to him as if he were about to have an operation, with the feigned empathy of hospital visitors. That moron Pérez was going off to work just as he had done every morning for years, and in the evening, after doing his shopping at the usual places, he would collapse, blissfully happy, on to his trusty old sofa in front of the TV, snuggling into his usual routine, sure of his immortality. At that moment, Brice would have loved to be that moron Pérez.

Breton Removals were barely five minutes late when they rolled up, but it seemed an eternity to him as he waited, leaning at the window and smoking one cigarette after another. It was a huge white lorry, a sort of refrigerated vehicle. Naturally, in spite of the official notices reserving the space between such and such times, a BMW had flouted the rules and parked right outside his apartment. The four Bretons (only one of whom actually was, Brice learned later) shifted the car in five minutes flat, as easily as if it had been a bicycle. Supremely indifferent to the chorus of car horns behind them, they took their time manoeuvring into position, displaying with their Herculean strength the utmost disdain for the rest of humanity.

This was a crack fighting unit, a perfectly oiled machine, a band of mercenaries to whom Brice had just entrusted his life. He was simultaneously reassured and terror-struck. He took the precaution of opening the door in case they took it off its hinges when they knocked.

As in all good criminal bands, the shortest one was the leader. Mind you, what Raymond lacked in height he made up for in width. He looked like an overheated Godin stove. Perhaps it was an occupational hazard, but they were each reminiscent of a piece of furniture: the one called Jean-Jean, a Louis-Philippe chest of drawers; Ludo, a Normandy wardrobe; and the tall, shifty-looking one affectionately known as The Eel, a grandfather clock. This outfit of rascals with bulging muscles and smiles baring wolf-like teeth made short work of surveying the flat. Each of them exuded a smell of musk, of wild animal escaped from its cage. Strangely, Brice felt safe, as if he had bought himself a personal bodyguard. From that moment, however, came the nagging question: how much of a tip should he give?

In no time at all, the heavies toured the apartment, made an expert estimate of the volume of furniture and boxes, and concluded, ‘No problem. Let’s get on with it.’ And they set to with a will. Chests of drawers, wardrobes, tables and chairs were transformed by grey sheets into unidentifiable objects, disappearing one by one as if by magic, whereas, a few years earlier, Brice had sweated blood getting them in. Ditto with the boxes, which for the past month he had struggled to stack, and which now seemed to have no weight at all on the removal men’s shoulders. Despite the graceful little sideways jumps Brice executed to avoid them, each worker in his own way made it clear that he had no business getting under their feet: they knew what they were doing. At that point, the existential lack of purpose which had dogged him from earliest childhood assumed monumental proportions, and he suggested going to fetch them cold drinks.

‘Beer?’

‘Oh no! Orangina, or mineral water, still.’

Even rogues went on diets, did they?

The Arab man who ran the corner shop where Brice bought his alcohol was most surprised to see him buying such tame drinks.

‘What’s this, boss? Are you ill?’

‘No, it’s for the removal men.’

‘That’s it then; you’re leaving us?’

‘That’s life.’

‘What about your wife? Still no news?’

‘I’m hopeful.’

‘We’ll miss you, boss.’

Clearly, given the amount of money Brice handed over to him in a month, the man had every reason to regret his departure.

On his return to the apartment, nothing remained but the bed and the flock of grey fluff balls grazing along the skirting boards.

‘That was quick!’

‘We’re pros. We don’t hang around.’

The Eel’s back was drenched in sweat. With the well-worn blade of his pocket knife, he cut the excess from a length of twine tied round what must have been a TV. Hemp fibres floated for a moment in the emptiness of the apartment. Raymond appeared, grabbing a can of Orangina which he downed in one. He let out a long, loud burp and wiped his lips with the back of his hand.

‘Bloody intellectuals! You shouldn’t pile up boxes of books like that.’

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know.’

‘Well, you do now.’

After this glittering riposte, Raymond the Stove handed him a green sheet, a pink sheet and a yellow sheet, jabbing his index finger at the exact spot where Brice had to sign.

‘Right, Lyon to Valence, best allow a good hour. Since we’ll be having a snack en route, let’s say two-thirty in your little village.’

‘I’ll be waiting for you.’

‘Fine. See you in a bit.’

Brice felt something tighten in his chest at the slightly too manly handshake and, as he closed the front door behind him for the last time, he had a vague idea of what a heart attack would be like. There, it was over. Brice was quite stunned. He recalled the anecdote about a man who was about to have his head chopped off by an executioner famed for his skill.

‘Please, Monsieur le bourreau, make a good job of it.’

‘But I’ve done it, Monsieur!’

The stakes for the vines, black like burnt matchsticks and set in serried rows on the hillside, were reminiscent of some sort of military cemetery. Despite its name, Saint-Joseph’s Grande Rue was so narrow you could have clasped hands with your neighbour on the other side. The enterprise would have been futile, mind you, given all the blank façades with their closed shutters and bolted doors. No activity, not so much as a cat or dog, nothing except a bakery, which was shut that day, and a pharmacy at the entrance to the village. Its green cross, framed in the rear-view mirror, promised little in the way of entertainment. Only a sign stuck at a street corner pointing to ‘Martine Coiffure: Ladies’ and Gents’ Hair Salon’ might, at a pinch, suggest a modicum of frivolity. Otherwise, there was nothing but vineyard signs emblazoned with badly painted bunches of grapes, creaking to and fro on both sides of the road.

From within the stone church tower, which stood out against the grey-green wash of sky, the bell struck one with a deafening clang as Brice was drawing up outside the house, his house. Round one could begin.

‘What the hell am I doing here? What on earth possessed us to buy this dump? I must have been drunk. That’s it, I was drunk.’

The house seemed enormous, far bigger than when he had visited it two months earlier with Emma.

‘So, dining room and kitchen there, sitting room here, opening on to the terrace. On the first floor the bedrooms, bathroom (with a bath and two washbasins), study, and then, in the attic, your studio. Aren’t the beams magnificent? You’ll be able to work so well here!’

All Brice could recall of that visit were fragments, like those which come back to you from a long-gone dream. It was dark, and he was hungry and tired. The estate agent, squeezed into his cheap little pinstriped suit, had followed them round like a poodle and, since he had no sales pitch, turned on all the electric light switches – clickety click – to prove that everything had been redone.

‘Well, darling?’

To make the question go away, and with no thought for the consequences, he had said yes. In the car, Emma had taken him through in endless and minute detail the innumerable plans she had in mind for decorating, to turn the cavern into a veritable palace.

‘And did you see it’s all been completely redone? The electricity …’

‘That’s right. Clickety click.’

Now stone walls and ceilings weighed down by enormous beams were leaning in on him, menacingly. It was extremely cold, and dim like in a cave. He opened the blinds in the dining room and living room, but the dishwater-coloured light which poured in did nothing to warm the atmosphere. It was like being in an aquarium without the fish.

‘A burial plot for life, that’s what we’ve bought ourselves.’

He went from room to room, forming a cross with his body at each window as his outspread arms flung the shutters wide. From outside he might have been taken for a Swiss cuckoo clock. Bong, the church clock struck the half-hour on his head.

He set the electricity meter going, turned on the water heater and put on all the lights. Then, as there was no chair, he sat down on the stairs. There was something suspicious: the house had no smell, not even of damp, as is usual in houses which have been empty for months on end. Apart from some arachnid presences among the beams – and not many, at that – there was no sign of life. For the first time in his existence he was an owner. But an owner of what? Of an empty universe, round which the crackling of the match struck for his cigarette echoed in a semblance of the Big Bang.

The removal men were on time. At exactly half past two – the church clock testified to that – the giant lorry occupied the Grande Rue. The four Atlases were in a cheerful mood.

‘Your little village is nice. It makes a change for us from estates and high-rises in Vénissieux or Villeurbanne. There it is, then. Wow, your house is big!’

‘Yes, it is rather on the large side.’

‘And you’ll be living here all on your own?’

‘No, my wife’s joining me.’

‘Even for two, it’s really big. Right … Let’s get on with it, lads, shall we?’

Brice felt quite emotional at seeing them again. It was as if a boat had made landfall on his desert island. The man who had always been too proud to join a band, a group, any association whatsoever, found himself savouring the unquantifiable joy of merging into this mass of humans, one atom among many.

After taking the men on a quick tour of the house, Brice stationed himself at the entrance to the garage and, as each of the large items appeared before him, pronounced with the confidence of a man who knows what he’s about: ‘Dining room’, ‘Living room’, ‘Yellow bedroom’, ‘Blue bedroom’, ‘Study’, ‘Studio’ and so on. As for the countless boxes marked ‘Kitchen’, ‘Bathroom’, ‘Clothes’, ‘Books’ and particularly those which, as their contents were unknown, were labelled vaguely ‘Misc.’, he had them piled up in the garage. They could be dealt with later. It took only a couple of hours. Once the essentials – beds, wardrobes, chests of drawers, tables, armchairs and sofas – had found appropriate places, it began to look like a real house. That is to say, you could sit in different parts of it, eat and maybe even sleep there.

‘There you are, home.’

‘Is that it?’

‘Well, yes.’

Brice was struggling to get used to the idea that they were going, leaving him on his own. He was gripped by a sort of panic.

‘There’s a café on the main road. Can I buy you a drink?’

‘That’s kind, but we need to get back. We’ve a life outside the job.’

‘Of course, I quite understand.’

Raymond proudly refused the tip Brice proffered, but consented to shake his hand. With the fifty-euro note still in his hand, and a tear in his eye, he watched the lorry manoeuvre then disappear round the corner of the road. A few drops of rain splashed down at his feet, and spread like ink on blotting paper. No two fell in the same spot.

That evening he had to eat, not out of greed or pleasure, but simply because unless a human being takes nourishment, he dies. In the garage he counted no fewer than eleven boxes which belonged in the kitchen and – surprise, surprise – most of them were behind the ones filled with books, which he had to move at the risk of hurting his back. Emma was unreasonably fond of kitchenware. There was enough to fit out a restaurant: plates of all sizes, soup tureens, sauce boats, fruit bowls, tea and coffee services; dishes for tarts, fish and asparagus; dishes made of silver, porcelain and earthenware; water glasses, wine glasses, whisky glasses; canteens of cutlery both antique and contemporary; sets of saucepans, castiron casserole dishes, a wok, a rice cooker, a tagine … and all in pristine condition for the good reason that Emma never cooked, and preferred to invite friends to a restaurant rather than entertain them at home. The yoghurt maker, blender and various other gadgets had not even made it out of their original packaging. When it was just the two of them, something frozen went into the microwave and … ping!