Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Vultures at least have the decency to wait until their prey is dead before they rip it to pieces . . .At the home in the mountains he shares with his put-upon nurse, Thérèse, cantankerous retiree Édouard Lavenant is attempting to write his memoirs when a visitor calls, claiming to be his long-lost son. Jean-Baptiste's presence seems to bring about a softening of Édouard's temper, but the family reunion is soon threatened by the local vultures circling overhead . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 205

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Pascal Garnier:

‘Horribly funny … appalling and bracing in equal measure ’

John Banville

‘Garnier plunges you into a bizarre, overheated world, seething death, writing, fictions and philosophy. He ’s a trippy, sleazy, sly and classy read.’

A. L. Kennedy

‘The final descent into violence is worthy of J. G. Ballard. 4 stars’ The Independent

‘Combines a sense of the surreal with a ruthless wit’

The Observer

‘Reminiscent of Joe Orton and the more impish films of Alfred Hitchcock and Claude Chabrol’

Sunday Times

‘Tense, strange, disconcerting and slyly funny’

Sunday Times

‘A brilliant exercise in grim and gripping irony, it makes you grin as well as wince.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘The combination of sudden violence, surreal touches and bone-dry humour have led to Garnier’s work being compared with the films of Tarantino and the Coen brothers.’

Sunday Times

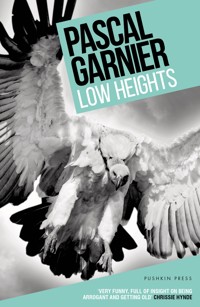

Low Heights

Pascal Garnier

Translated from the French by Melanie Florence

The best way to avoid getting lost is not to know where you are going

Jean-Jacques Schuhl

Contents

‘Today’s programme is all about stomach ulcers and with us in the studio we have Professor Chotard from …’

Monsieur Lavenant clenched his fist in irritation, as if he were crumpling up an invisible sheet of paper.

‘Will you change the station, Thérèse? Or even better, turn the radio off altogether.’

‘There.’

The presenter’s nasal voice was replaced by the roar of the engine. Monsieur Lavenant tugged at the seat belt, which was digging into his left shoulder.

‘In any case, it’s ridiculous to try to listen to the radio in these gorges – you know perfectly well it’s impossible to pick anything up clearly.’

‘It was you who asked me to turn it on, Monsieur.’

‘Hmm, well … We weren’t in a gorge a minute ago.’

The river Aygues wound its way to the right of the road along the sheer rock. With the non-stop torrential rain of the past few days, its coffee-coloured water carried along dead branches which gathered in the rocky river bends like sets of pick-up sticks. Above the cliffs, birds bounced acrobatically on the taut blue trampoline of the sky. Nature was drying her sorrowful tears of the previous day. The car swerved.

‘Look out, Thérèse!’

‘That’s what I’m doing, Monsieur. There was a big stone in the middle of the road. It’s because of the storms.’

‘You’re driving too fast.’

‘A minute ago you were criticising me for going too slowly.’

‘A minute ago we were on a straight road. You drive too fast when you shouldn’t, and too slowly when you need to accelerate. Anyway, in a car like this!’

‘It may be old but it serves me well. And you too.’

‘It stinks. It stinks of petrol and wet dog.’

‘I’ve never had a dog.’

‘You must have had one in the car then. I may be gaga but I can still recognise the smell of damp dog!’

Thérèse gave up. Whatever he said, whatever he did, the old boy wouldn’t succeed in spoiling the good mood she had been in since the moment she woke up. She felt serene, happy with the sort of happiness which hits you out of the blue.

‘Why are you smiling?’

‘No reason. The weather’s fine.’

‘The weather’s fine … Pah! In the desert it’s fine the whole time – d’you think the Bedouin are laughing?’

‘I don’t know, Monsieur. I’ve never been there.’

‘Well, I have, and believe me, there ’s no reason to smile. Slow down, Thérèse, we’re coming to the tunnel!’

‘I know, Monsieur. I know the road.’

‘Exactly! That’s why accidents happen. You know, you’re confident, and then wham! Vigilance, Thérèse, vigilance, at all times. It only needs a second’s lack of concentration … Look there, what did I tell you? English bastard!’

Monsieur Lavenant’s voice yelling through the open window was quickly swallowed up in the dark shadow of the tunnel, while the camper van which had almost clipped them disappeared in the rear-view mirror. At the exit, the sun striking a layer of rock made them blink. The geological strata formed swirls, folds of ochre, gold or incandescent white trimmed with the green fur of spindly oak trees, all their roots clinging onto the slightest toehold in the ground. The birth of the world could be read there, its bursts of energy, its hesitations, twists and turns, its centuries-long periods of stagnation and thunderous eruptions. Now and then, perfumed clouds of thyme or lavender wafted in, accompanied by the non-stop chirping of the crickets.

‘What about …’

‘About?’

‘I was going to say something silly, Monsieur.’

‘Say it then.’

‘What about having a picnic after we’ve been to the market?’

‘That’s not silly, that’s downright stupid! Have you been drinking, Thérèse? I’ve heard it all now! Picnic? Do you think you’re on holiday or something?’

‘I’m sorry, Monsieur.’

‘A picnic! And then a little dip in the Aygues, and in the evening maybe a dance, under paper lanterns? You’d be better off looking where you’re going. Here, switch the radio on again, we’re out of the gorge. I’d rather listen to the world’s bad news than your ramblings.’

‘Very well, Monsieur.’

The first cherries were barely ripe, yet the market in Nyons was teeming like high summer. Space was limited and they had been forced to park well beyond the Pont Roman, which had, of course, only exacerbated Monsieur Lavenant’s bad mood.

‘Just look at that! English, Dutch, Germans, Belgians … Do I go and do my shopping in their countries? No! You’d think we were still under the Occupation.’

‘I could easily have done the shopping on my own; you didn’t have to come.’

‘That’s right, you’d like me to stay shut up in my hole like a rat. I do still have the right to go out, you know.’

‘Why don’t you wait for me nice and quietly on the café terrace with your newspaper and a cold drink?’

‘That’s exactly what I had in mind. But don’t dawdle like last time. It doesn’t take three hours to buy a kilo of tomatoes. Have you got the list?’

‘I have. See you later, Monsieur.’

‘And don’t let anyone rip you off, we ’re not tourists.’

Seated at a small table in the shade of a blue-and-white-striped awning, he watched Thérèse go off, basket in hand, and melt into the brightly coloured crowd. As soon as she was out of sight he felt a vague anxiety, a sense of having been abandoned. He shrugged his shoulders and curtly ordered a pastis from the waitress who was bustling among the tables like a frantic insect.

Thérèse allowed herself to be carried along by the wave of passers-by, intoxicated by the infinite variety of colours, scents and sounds, as if at the heart of a giant kaleidoscope. Bodies scantily dressed in the lightest of fabrics rubbed against hers and she experienced the same giddiness as she had at dances in her youth. She desired everything, and everything was there. After the gloomy days counted off like rosary beads in Monsieur Lavenant’s joyless house, this was a sort of resurrection and she made the most of it, every pore straining for the tiniest atom of life. She criss-crossed Place du Docteur Bourdongle, enclosed by arcades whose violet shadow suggested stolen kisses, filling her basket with tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, basil, fromage frais, piping-hot bread. She tasted an olive here, a crouton dripping with virgin oil there, a slice of saucisson, a spoonful of honey …

As she made her way back, having come to the end of her shopping list, she stopped short in front of a stall selling hats, dozens and dozens of hats …

GREAT DEALS!

FREE! We will clear your attic, cellar or whole house … 500 F plus paid for German helmets, uniforms, other historical memorabilia, Resistance, militia, US …

PRIV. INDIVID. SEEKS OLD MILITARY objects, from flintlocks to caplocks, matchlocks, percussion caps, trigger guards, various barrel bands, even in poor condition …

Monsieur Lavenant pushed his newspaper away and stared mournfully at his empty pastis glass. In theory he wasn’t allowed more, but since sucking the ice cube, all he could think of was having another. There was something indecent about feeling so good and everything in him rebelled at the idea of calling the waitress again. Yet he was dying to. He would have to make up his mind before Thérèse came back. He glanced at his watch but as he didn’t know how long he’d been there, he was none the wiser. The sight of the crippled hand to which his watch was attached decided it for him. It was scrawny and hooked, like a bird of prey’s talon, the hand of an Egyptian mummy, of use to him now only as a paperweight to stop the newspaper from blowing in the breeze.

‘The state I’m in already … Fuck it! I can do what I want.’ Immediately, his right arm shot up and the crow in a white blouse and black skirt replaced his empty glass with a new one which he half emptied in order to fool Thérèse, before becoming engrossed once more in the indescribable experience of reading the classifieds.

BULTEX SOFA BED, new, yellow. 1300 F.

WIN BIG ON THE HORSES! 70% success rate for our tip with good odds. WATCH THIS SPACE FOR RELIABLE INFO!

HORSE MANURE TO GIVE AWAY.

TWO THOUSAND-LITRE SEPTIC TANKS.

BRIDAL GOWN, size 38 + veil and tiara. 1000 F.

For a moment he saw it floating before him, a wispy cloud of white muslin. Deep in his wizened heart, something came loose. How long was it since he’d just let go, stretched out on the grass and watched the clouds go by? Years …

‘There now, I wasn’t too long, was I?’ Thérèse’s voice jolted him back to reality.

‘What have you got on your head?’

‘A hat.’

‘A hat!’

‘Well, you’re wearing one.’

‘It’s different for me. I can’t tolerate the sun. My hat is … useful.’

‘Well, mine is a hat that I like.’

It was a small straw hat with a wide brim which cast a veil of shadow over her shiny, slightly puffy face. Her violet eyes, the only beautiful thing about her, were sparkling with mischief, almost impudence. Monsieur Lavenant tried unsuccessfully to find something to say to make her lower them, but could only snigger and look away.

‘At the end of the day, you’re the one wearing it. Now, what have you brought for the picnic?’

‘The picnic?’

‘Yes, the picnic. Have you lost your wits or something?’

‘I thought that …’

‘You thought that … You thought … I’ve changed my mind, that’s all. I’m entitled to do that, aren’t I?’

‘Oh, it doesn’t bother me. Quite the reverse; it’s such lovely weather. We ’ve got all we need: melon, tomatoes, cheese and an excellent ham.’

Paying for his drinks, he couldn’t hide the fact that he’d had two pastis and she raised her eyebrows indulgently.

‘Yes, I’ve drunk two pastis; it won’t kill me.’

Monsieur Lavenant decided they should take the Défilé de Trente Pas and look for a place to stop on the way to the Lescou Pass where the air was cooler. The road was very narrow and winding. Thérèse drove carefully, sounding her horn at every bend since it was impossible to see round them. The walls of rock were so close together that it felt like being a bookmark between the pages of an ancient tome exuding a strong smell of mould. It was very impressive but slightly anxiety-provoking. The dense vegetation screened the river below, whose presence was suggested only by a guttural roar, an uninterrupted chant. Neither of them uttered a word until they were out of the gorge, and as one they sighed with relief when the little car came onto the road to the pass. The sun was sounding a fanfare and the clumps of trees were thinning out the higher they climbed. Their stomachs rumbled meaningfully and, quite independently, Thérèse to the left and Monsieur Lavenant to the right, they scoured the horizon for a favourable picnic spot.

‘Take that little one on the right! There, right away!’

Having missed it, Thérèse reversed and turned onto the track. It led to a not very attractive ruin without the slightest patch of shade. The view of the valley was magnificent but all they could think of was the Drummond family murders or something else sinister and tragic. Despite the hunger gnawing at them, they turned round. A little further on, a side road led them straight to a farm, out of which shot a large hound, fangs bared, slavering all over its chops and howling blue murder. Once more they had to turn back. Monsieur Lavenant was bright red, his jaw clenched in a silent fury which crept through him like poison.

‘Are you trying to make us die of hunger or something? It’s just like you to do something like this!’

‘You were the one who was set on coming here. You know the area, apparently.’

‘It’s changed! Everything changes the whole time. How do you expect me to know where we are? Anyway, you drive too fast so obviously we’re going to miss the best places. We passed dozens as we came out of the ravine.’

‘You wanted to go higher up because of the air.’

‘So it’s my fault now! Was I the one who had this stupid picnic idea? I loathe picnics. You always end up next to a rubbish tip, being eaten alive by insects, sitting on a pile of stones, with greasy hands and warm drinks – that’s if there ’s not some local halfwit hiding in the bushes waiting to cut your throat during your siesta.’

‘Let’s go home then.’

‘Yes. We will go home, we’ve wasted enough time.’

Each of them had retreated into a palpable sulk when, at the entrance to a hamlet, they noticed a tiny chapel in a hollow, with a small meadow in front of it, shaded by three magnificent lime trees. A stream meandered along the bottom of the field. Thérèse braked and gave Monsieur Lavenant a questioning look.

‘We ’ve come this far, we might as well have a go.’

Thérèse parked the car in the shade of one of the big trees. The new-cut grass gave off a smell of hay which mingled with the pollen from the limes. Not one fly, not one mosquito. The serenity of the modest chapel with its lime-washed façade surmounted by a silent bell banished all dark thoughts. It was paradise as conceived by a six-year-old. In spite of all his bad faith Monsieur Lavenant had to give in.

‘Take a seat under that tree where it’s nice and flat. I’ll see to everything.’

The bark of the tree trunk seemed more comfortable than the velvet of his armchair. He put his crippled hand between his thighs, and removed his hat with the other. A breath of wind caressed the skin on the top of his head, ruffling the few hairs which crowned it like swansdown, and then swooped down the open neck of his shirt. In the far distance a cock was crowing, and a dog barked in response. He closed his eyes and opened his mouth, since he had nothing better to do. Little by little the rapid pulsing of blood in his veins slowed to match the peaceful rhythm of the lime tree ’s sap, which he could feel circulating at his back, from the nape of his neck to his waist. C’est un trou de verdure qui mousse de rayons … He would really have liked to remember the poem … C’est un trou de verdure …

‘There, it’s ready!’

Thérèse was smiling, cheeks flushed, hat tilted back, kneeling down, like the little girl she must once have been, proud of her dolls’ tea set. In the absence of a plate, the melon slices, ham and cheese were set out on their wrappers. There was even a bottle of rosé, cooling inside a towel she had soaked in the stream.

‘If I’d known, I’d have brought glasses, plates and cutlery …’

Something Monsieur Lavenant hadn’t felt since … maybe the end of the world caught in his throat, prickled his nose and brought deliciously salty water to his eyes.

They made a good meal of the melon, ham, tomatoes and cheese she spread on slices of crusty bread, like canapés, using a small knife she always carried in the glove box. The wine was barely chilled, but they drank half of it straight from the bottle like savages. Monsieur Lavenant got carried away, describing the gourmet meals he’d had in some of the world’s top restaurants. Thérèse loved food and he remembered that he used to as well. Then, like a child falling asleep at the table, he stretched out, good arm beneath his head, and promptly began to snore.

Thérèse cleared away the leftovers, put the cork back in the bottle, gathered up the melon skins and the ham and cheese rinds and put them into a plastic bag, scattered the crumbs for the birds and lay down in her turn – but only once she’d given a satisfied glance at her hat. There are days like that.

The day was at its hottest when Monsieur Lavenant opened his eyes. He stretched, yawning like a lion. If his right arm obeyed orders, the left remained stubbornly bent, like an iron hook. He had had this disability for a year now and was relatively used to it but it still astonished him sometimes when he woke up. He lay flat again. The play of sunlight through the lime ’s foliage marbled his skin blue and gold. If Cécile had still been alive and there next to him, he would probably have made love to her. She would have feigned sleep and put up with it, with a groan. But Cécile had died suddenly of cancer almost ten years ago. He had never accepted being left behind, just as certain blind people will never get used to sightlessness. He had been angry with her and, out of spite, had thrown himself into his business with the merciless efficiency of the most ruthless predator. It wasn’t for the money, as he was more than comfortably off, but in order to anaesthetise himself, wear himself out, cause himself pain as others do pleasure, until that evening in September when an episode in a grand Lyon restaurant had forced him to pack it all in. He had felt a rush of hot air to his face, his legs gave way beneath him and his reflection disappeared from the spotless tiles above the urinals. His last thought was of his flies, which he hadn’t had time to do up.

After his stay in hospital, and on his doctor’s advice, he had decided to leave his apartment and office in Lyon and to move into the house at Rémuzat which had been in his wife’s family and where he had set foot only once or twice. That was as good as anywhere else. Since his state of health made nursing care necessary he had recruited Thérèse through a specialist agency. In two months’ time this odd couple would have been together for a year and he had no idea how long this might last, the future not being on his agenda any more.

A lime blossom, a tiny helicopter, came to land on his chest. He hadn’t drunk much but his mouth was as ‘caramelised’ as after a heavy night. Propping himself up on one elbow, he downed what was left in the bottle of Evian, which a ray of sun had heated almost to boiling point.

Thérèse was sleeping with her mouth open and her red hair (white in places) plastered to her forehead. Her hat had left a red mark on her skin. A few drops of sweat were visible under her arms. Her dress was rucked up in the brazenness of sleep, exposing soft, white calves lined with blue veins which made him think of certain artisan sausages he had a taste for. She was neither beautiful nor ugly, simply robust. Aside from her professional references he knew nothing about her except that she was Alsatian, from Colmar. It was as if he were seeing her for the first time, seeing her as something more than a medical aid, and it disturbed him. One of Thérèse’s knees was marked by a crescent-shaped scar, some childhood accident, a fall from a bicycle perhaps … Without thinking he went to stroke it, but at that moment Thérèse opened one eye and he put his hand down again, turning red.

‘I’m sorry, I think I fell asleep …’

She sat up, tugging her dress down over her knees and tidying her hair. A few blades of grass were sticking out of it, like pins. Once again she was smiling. The low neckline of her dress revealed a beige bra strap, more suggestive of a hernia bandage than of sexy underwear.

‘Perhaps we ought to be thinking of getting back, it’s nearly four o’clock.’

‘We ought to, yes.’

‘What a lovely place, though … Imagine, some people actually live here …’

A quarter of an hour later, the car started bumping gently along the track. Before they came to the road, Monsieur Lavenant met Thérèse’s gaze in the rear-view mirror. A tear hung on her eyelashes.

‘Thérèse, are you crying?’

She sniffed, wiped the corner of her eye with the back of her hand, and shifted into first gear.

‘No, it’s nothing, Monsieur.’

‘Yes, you are, you’re crying. What’s wrong?’

‘I’m fifty-two today, Monsieur. It’s my birthday. Silly, isn’t it?’

FOR FARMHOUSE RESTORATION, Apt area, seek couple as caretakers, no family ties, motivated, stable, gd health. M 40–55 gen. builder for outside work, F to look after well-appointed house, no visitors allowed. Furnished accommodation + salary, to start 08/01. Send CV + salary expectations.

ICE-CREAM SELLER WANTED, Male, Ruoms area, for summer season.

The other advertisements disappeared under the salad leaves Thérèse was rinsing. Even if these household tasks – cooking, washing, cleaning – were not high on her list of duties, they were nevertheless the ones she liked best. She had her nursing diploma, of course, but very early on, after two or three years of hospital work, she had chosen to practise her profession in a way that let her move around. Maybe it was the result of her childhood as an orphan, hopping from foster family to hostel as if over stepping stones, until in the end the only place she felt at home was in other people’s houses. Twenty-five years of spending weeks, months, even years with her ‘clients’ had given her a quite remarkable capacity to adapt. A split second in the kitchen and she would know where the vegetable peeler was, what sort of coffee maker they used and whether or not they skimped on cleaning products, or, in the living room, what wasn’t to be moved in any circumstances, ornaments, rugs, the way the curtains hung or, in the bedroom, a very specific manner of arranging the pillows, all these little habits which mean that no interior is anything like another, although they may at first sight appear to be identical.