Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Gallic Noir

- Sprache: Englisch

Ennui, dislocation, alienation, estrangement - these are the colours on Garnier's palette. And somehow, darkly, he makes them almost funny. I could compare him with JG Ballard or with Michel Houellebecq or Daniel Davies. He's been compared with Georges Simenon and Cormac McCarthy and with Patricia Highsmith. But really, his books are out there on their own, short, jagged and exhilarating, unexpected slaps around the face that make you laugh with surprise while you spin around to see who did it. His work is really like no-one else's and it is worth reading everything of his that you can. Before it's too late... ~ STANLEY DONWOOD

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 666

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Pascal Garnier

Pascal Garnier was born in Paris in 1949. The prize-winning author of over sixty books, he remains a leading figure in contemporary French literature, in the tradition of Georges Simenon. He died in 2010.

Emily Boyce

Emily Boyce is in-house translator and editor at Gallic Books.

Jane Aitken

Jane Aitken studied history at St Annes College, Oxford. She is a publisher and translator from the French.

Melanie Florence

Melanie Florence teaches at The University of Oxford and translates from the French.

‘Wonderful … Properly noir’ Ian Rankin

‘Garnier plunges you into a bizarre, overheated world, seething death, writing, fictions and philosophy. He’s a trippy, sleazy, sly and classy read’ A. L. Kennedy

‘Horribly funny … appalling and bracing in equal measure. Masterful’ John Banville

‘Ennui, dislocation, alienation, estrangement – these are the colours on Garnier’s palette. His books are out there on their own: short, jagged and exhilarating’ Stanley Donwood

‘The combination of sudden violence, surreal touches and bonedry humour have led to Garnier’s work being compared with the films of Tarantino and the Coen brothers’ Sunday Times

‘Deliciously dark … painfully funny’ New York Times

‘A mixture of Albert Camus and JG Ballard’ Financial Times

‘A brilliant exercise in grim and gripping irony; makes you grin as well as wince’ Sunday Telegraph

‘A master of the surreal noir thriller – Luis Buñuel meets Georges Simenon’ Times Literary Supplement

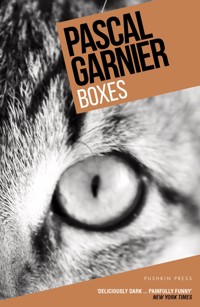

Boxes

The Front Seat Passenger

The Islanders

Moon in a Dead Eye

‘Garnier’s world exists in the cracks and margins of ours; just off-key, often teetering on the surreal, yet all too plausible. His mordant literary edge makes these succinct novels stimulating and rewarding’ Sunday Times

‘Small but perfectly formed darkest noir fiction told in spare, mordant prose … Recounted with disconcerting matter-of-factness, Garnier’s work is surreal and horrific in equal measure’ Guardian

‘Tense, strange, disconcerting and slyly funny’ Sunday Times

‘Combines a sense of the surreal with a ruthless wit’ The Observer

‘Devastating and brilliant’ Sunday Times

‘Bleak, often funny and never predictable’ The Observer

‘Reminiscent of Joe Orton and the more impish films of Alfred Hitchcock and Claude Chabrol’ Sunday Times

‘Brief, brisk, ruthlessly entertaining … Garnier makes bleakness pleasurable’ John Powers, NPR

‘This is tough, bloody stuff, but put together with a cunning intelligence’ Sunday Times

‘A guaranteed grisly thriller’ ShortList

‘Garnier’s world exists in the cracks and margins of ours; just off-key, often teetering on the surreal, yet all too plausible. His mordant literary edge makes these succinct novels stimulating and rewarding’ Sunday Times

Boxes

The Front Seat Passenger

The Islanders

Moon in a Dead Eye

by Pascal Garnier

Pushkin Vertigo

A Gallic Book

Boxes

First published in France as Cartons by Zulma, 2012

Copyright © Zulma, 2012

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2015

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Gallic Books

The Front Seat Passenger

First published in France as La Place du mort by Zulma, 2010

Copyright © Zulma, 2010

English Translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Gallic Books

The Islanders

First published in France as Les Insulaires by Zulma, 2010

Copyright © Zulma, 2010

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2014

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Gallic Books

Moon in a Dead Eye

First published in France as Lune captive dans un œil mort by Zulma, 2009

Copyright © Zulma, 2009

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Gallic Books

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-805336-04-4

Typeset in Fournier MT by Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

Contents

Boxes

The Front Seat Passenger

The Islanders

Moon in a Dead Eye

Boxes

translated from the French by Melanie Florence

For Laurence

Brice sat on a metal trunk he had struggled to close, with a silly little rhyme going round and round in his head: ‘An old man lived in a cardboard box / With a squirrel, a mouse and a little red fox.’ Cardboard boxes: he was completely surrounded by them, in piles stretching from floor to ceiling, so that in order to go from one room to another it was necessary to turn sideways on, like in an Egyptian wall painting. That said, there was no longer any reason to go into another room since, boxes aside, they were all as empty as the fridge and the household drawers. He was the sole survivor of the natural disaster that at one time or another strikes us all, known as moving house.

Following a terrible night’s sleep in a room which had already ceased to be his, he had stripped the bed of its sheets, quilt and pillows, and stuffed it all into a big checked plastic bag he had set aside the night before. He had a quick wash, taking care not to spray toothpaste on the mirror, and dutifully inspected the place in case he had forgotten something. But no, apart from a piece of string about a metre and a half long which he unthinkingly wound round his hand, there was nothing left but the holes made by nails and screws which had held up picture frames or shelves. For a brief moment he thought of hanging himself with the piece of string but gave up the idea. The situation was painful enough already.

There was still a good hour before Breton Removals would come to put an end to ten years of a life so perfect that it seemed it would last for ever.

That cold November morning he was furious with Emma for having left him helpless and alone, in the hands of the removal men, who in an hour’s time would descend like a swarm of locusts to ransack the apartment. Both strategically and psychologically, his position was untenable, so he decided to go out for a coffee while he waited for the world to end.

The neighbourhood seemed already to have forgotten him. He saw no one he knew, with the result that, instead of going to his usual bistro, he chose one he had never set foot in before. Above the bar, a host of notices informed the clientele that the telephone was reserved for customers, the use of mobiles was strongly discouraged, it would be wise to beware of the dog and, of course, no credit would be given. A guy with dyed red-blond hair came in, issuing a general ‘Hi!’ He was some sort of actor or comedian Brice had seen on TV. For a good few minutes he tried unsuccessfully to remember his name, then since this quest – as annoying as it was futile – led nowhere, he persuaded himself he had never known it. Behind him, wafts of disinfectant and urine came from the toilet doorway, mingling with the smell of coffee and dead ashtrays. A sort of black tide made his stomach heave at the first mouthful of espresso. He sent a few coins spinning on to the bar and made his escape, a bent figure with turned-up collar.

In the stairway he passed Monsieur Pérez, his upstairs neighbour.

‘Today’s the day, then?’

‘Yes, I’m just waiting for the removal men.’

‘It’ll seem strange for you, living in the countryside.’

‘A little, no doubt, to begin with.’

‘And particularly in your situation. Speaking of which, still no news of your lady?’

‘I’m hopeful.’

‘That’s good. I’m very partial to the countryside, but only for holidays, otherwise I don’t half get bored. Well, each to his own. Right then, good luck, and keep your chin up for the move. It’s just something you have to get through.’

‘Have a good day, Monsieur Pérez.’

For the past month Brice had felt like someone with a serious illness. Everyone talked to him as if he were about to have an operation, with the feigned empathy of hospital visitors. That moron Pérez was going off to work just as he had done every morning for years, and in the evening, after doing his shopping at the usual places, he would collapse, blissfully happy, on to his trusty old sofa in front of the TV, snuggling into his usual routine, sure of his immortality. At that moment, Brice would have loved to be that moron Pérez.

Breton Removals were barely five minutes late when they rolled up, but it seemed an eternity to him as he waited, leaning at the window and smoking one cigarette after another. It was a huge white lorry, a sort of refrigerated vehicle. Naturally, in spite of the official notices reserving the space between such and such times, a BMW had flouted the rules and parked right outside his apartment. The four Bretons (only one of whom actually was, Brice learned later) shifted the car in five minutes flat, as easily as if it had been a bicycle. Supremely indifferent to the chorus of car horns behind them, they took their time manoeuvring into position, displaying with their Herculean strength the utmost disdain for the rest of humanity.

This was a crack fighting unit, a perfectly oiled machine, a band of mercenaries to whom Brice had just entrusted his life. He was simultaneously reassured and terror-struck. He took the precaution of opening the door in case they took it off its hinges when they knocked.

As in all good criminal bands, the shortest one was the leader. Mind you, what Raymond lacked in height he made up for in width. He looked like an overheated Godin stove. Perhaps it was an occupational hazard, but they were each reminiscent of a piece of furniture: the one called Jean-Jean, a Louis-Philippe chest of drawers; Ludo, a Normandy wardrobe; and the tall, shifty-looking one affectionately known as The Eel, a grandfather clock. This outfit of rascals with bulging muscles and smiles baring wolf-like teeth made short work of surveying the flat. Each of them exuded a smell of musk, of wild animal escaped from its cage. Strangely, Brice felt safe, as if he had bought himself a personal bodyguard. From that moment, however, came the nagging question: how much of a tip should he give?

In no time at all, the heavies toured the apartment, made an expert estimate of the volume of furniture and boxes, and concluded, ‘No problem. Let’s get on with it.’ And they set to with a will. Chests of drawers, wardrobes, tables and chairs were transformed by grey sheets into unidentifiable objects, disappearing one by one as if by magic, whereas, a few years earlier, Brice had sweated blood getting them in. Ditto with the boxes, which for the past month he had struggled to stack, and which now seemed to have no weight at all on the removal men’s shoulders. Despite the graceful little sideways jumps Brice executed to avoid them, each worker in his own way made it clear that he had no business getting under their feet: they knew what they were doing. At that point, the existential lack of purpose which had dogged him from earliest childhood assumed monumental proportions, and he suggested going to fetch them cold drinks.

‘Beer?’

‘Oh no! Orangina, or mineral water, still.’

Even rogues went on diets, did they?

The Arab man who ran the corner shop where Brice bought his alcohol was most surprised to see him buying such tame drinks.

‘What’s this, boss? Are you ill?’

‘No, it’s for the removal men.’

‘That’s it then; you’re leaving us?’

‘That’s life.’

‘What about your wife? Still no news?’

‘I’m hopeful.’

‘We’ll miss you, boss.’

Clearly, given the amount of money Brice handed over to him in a month, the man had every reason to regret his departure.

On his return to the apartment, nothing remained but the bed and the flock of grey fluff balls grazing along the skirting boards.

‘That was quick!’

‘We’re pros. We don’t hang around.’

The Eel’s back was drenched in sweat. With the well-worn blade of his pocket knife, he cut the excess from a length of twine tied round what must have been a TV. Hemp fibres floated for a moment in the emptiness of the apartment. Raymond appeared, grabbing a can of Orangina which he downed in one. He let out a long, loud burp and wiped his lips with the back of his hand.

‘Bloody intellectuals! You shouldn’t pile up boxes of books like that.’

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know.’

‘Well, you do now.’

After this glittering riposte, Raymond the Stove handed him a green sheet, a pink sheet and a yellow sheet, jabbing his index finger at the exact spot where Brice had to sign.

‘Right, Lyon to Valence, best allow a good hour. Since we’ll be having a snack en route, let’s say two-thirty in your little village.’

‘I’ll be waiting for you.’

‘Fine. See you in a bit.’

Brice felt something tighten in his chest at the slightly too manly handshake and, as he closed the front door behind him for the last time, he had a vague idea of what a heart attack would be like. There, it was over. Brice was quite stunned. He recalled the anecdote about a man who was about to have his head chopped off by an executioner famed for his skill.

‘Please, Monsieur le bourreau, make a good job of it.’

‘But I’ve done it, Monsieur!’

The stakes for the vines, black like burnt matchsticks and set in serried rows on the hillside, were reminiscent of some sort of military cemetery. Despite its name, Saint-Joseph’s Grande Rue was so narrow you could have clasped hands with your neighbour on the other side. The enterprise would have been futile, mind you, given all the blank façades with their closed shutters and bolted doors. No activity, not so much as a cat or dog, nothing except a bakery, which was shut that day, and a pharmacy at the entrance to the village. Its green cross, framed in the rear-view mirror, promised little in the way of entertainment. Only a sign stuck at a street corner pointing to ‘Martine Coiffure: Ladies’ and Gents’ Hair Salon’ might, at a pinch, suggest a modicum of frivolity. Otherwise, there was nothing but vineyard signs emblazoned with badly painted bunches of grapes, creaking to and fro on both sides of the road.

From within the stone church tower, which stood out against the grey-green wash of sky, the bell struck one with a deafening clang as Brice was drawing up outside the house, his house. Round one could begin.

‘What the hell am I doing here? What on earth possessed us to buy this dump? I must have been drunk. That’s it, I was drunk.’

The house seemed enormous, far bigger than when he had visited it two months earlier with Emma.

‘So, dining room and kitchen there, sitting room here, opening on to the terrace. On the first floor the bedrooms, bathroom (with a bath and two washbasins), study, and then, in the attic, your studio. Aren’t the beams magnificent? You’ll be able to work so well here!’

All Brice could recall of that visit were fragments, like those which come back to you from a long-gone dream. It was dark, and he was hungry and tired. The estate agent, squeezed into his cheap little pinstriped suit, had followed them round like a poodle and, since he had no sales pitch, turned on all the electric light switches – clickety click – to prove that everything had been redone.

‘Well, darling?’

To make the question go away, and with no thought for the consequences, he had said yes. In the car, Emma had taken him through in endless and minute detail the innumerable plans she had in mind for decorating, to turn the cavern into a veritable palace.

‘And did you see it’s all been completely redone? The electricity …’

‘That’s right. Clickety click.’

Now stone walls and ceilings weighed down by enormous beams were leaning in on him, menacingly. It was extremely cold, and dim like in a cave. He opened the blinds in the dining room and living room, but the dishwater-coloured light which poured in did nothing to warm the atmosphere. It was like being in an aquarium without the fish.

‘A burial plot for life, that’s what we’ve bought ourselves.’

He went from room to room, forming a cross with his body at each window as his outspread arms flung the shutters wide. From outside he might have been taken for a Swiss cuckoo clock. Bong, the church clock struck the half-hour on his head.

He set the electricity meter going, turned on the water heater and put on all the lights. Then, as there was no chair, he sat down on the stairs. There was something suspicious: the house had no smell, not even of damp, as is usual in houses which have been empty for months on end. Apart from some arachnid presences among the beams – and not many, at that – there was no sign of life. For the first time in his existence he was an owner. But an owner of what? Of an empty universe, round which the crackling of the match struck for his cigarette echoed in a semblance of the Big Bang.

The removal men were on time. At exactly half past two – the church clock testified to that – the giant lorry occupied the Grande Rue. The four Atlases were in a cheerful mood.

‘Your little village is nice. It makes a change for us from estates and high-rises in Vénissieux or Villeurbanne. There it is, then. Wow, your house is big!’

‘Yes, it is rather on the large side.’

‘And you’ll be living here all on your own?’

‘No, my wife’s joining me.’

‘Even for two, it’s really big. Right … Let’s get on with it, lads, shall we?’

Brice felt quite emotional at seeing them again. It was as if a boat had made landfall on his desert island. The man who had always been too proud to join a band, a group, any association whatsoever, found himself savouring the unquantifiable joy of merging into this mass of humans, one atom among many.

After taking the men on a quick tour of the house, Brice stationed himself at the entrance to the garage and, as each of the large items appeared before him, pronounced with the confidence of a man who knows what he’s about: ‘Dining room’, ‘Living room’, ‘Yellow bedroom’, ‘Blue bedroom’, ‘Study’, ‘Studio’ and so on. As for the countless boxes marked ‘Kitchen’, ‘Bathroom’, ‘Clothes’, ‘Books’ and particularly those which, as their contents were unknown, were labelled vaguely ‘Misc.’, he had them piled up in the garage. They could be dealt with later. It took only a couple of hours. Once the essentials – beds, wardrobes, chests of drawers, tables, armchairs and sofas – had found appropriate places, it began to look like a real house. That is to say, you could sit in different parts of it, eat and maybe even sleep there.

‘There you are, home.’

‘Is that it?’

‘Well, yes.’

Brice was struggling to get used to the idea that they were going, leaving him on his own. He was gripped by a sort of panic.

‘There’s a café on the main road. Can I buy you a drink?’

‘That’s kind, but we need to get back. We’ve a life outside the job.’

‘Of course, I quite understand.’

Raymond proudly refused the tip Brice proffered, but consented to shake his hand. With the fifty-euro note still in his hand, and a tear in his eye, he watched the lorry manoeuvre then disappear round the corner of the road. A few drops of rain splashed down at his feet, and spread like ink on blotting paper. No two fell in the same spot.

That evening he had to eat, not out of greed or pleasure, but simply because unless a human being takes nourishment, he dies. In the garage he counted no fewer than eleven boxes which belonged in the kitchen and – surprise, surprise – most of them were behind the ones filled with books, which he had to move at the risk of hurting his back. Emma was unreasonably fond of kitchenware. There was enough to fit out a restaurant: plates of all sizes, soup tureens, sauce boats, fruit bowls, tea and coffee services; dishes for tarts, fish and asparagus; dishes made of silver, porcelain and earthenware; water glasses, wine glasses, whisky glasses; canteens of cutlery both antique and contemporary; sets of saucepans, cast-iron casserole dishes, a wok, a rice cooker, a tagine … and all in pristine condition for the good reason that Emma never cooked, and preferred to invite friends to a restaurant rather than entertain them at home. The yoghurt maker, blender and various other gadgets had not even made it out of their original packaging. When it was just the two of them, something frozen went into the microwave and … ping!

Box after box was slashed open with a Stanley knife in his search for a tin of food. Every five minutes, the light switch would time out and he would have to feel his way back across the garage to put it on again, bumping his foot or his shin against the scattered boxes. At last he found a tin, pike quenelles in ‘Nantua sauce’, only a few weeks past their use-by date. Sadly the tin was lacking the handy little ring which would have allowed him to free the contents without the aid of a tin-opener. The search through the boxes resumed, increasingly frantic now. Aside from a bottle of Bordeaux, he found virtually everything he did not need: pastry wheel, ice-cream scoop, nutcrackers, cake slice, olive pitter, snail tongs – but the tin-opener still evaded detection. Yet they did have one, he was sure of it, a fancy streamlined model which was the work of a famous designer, and not in fact terribly practical. They had bought it at vast expense in a specialist shop across from Les Halles in Lyon.

Brice had first met Emma at a gallery during the private view of a Hungarian artist whose ‘thing’ was using varnish to fossilise the remains of goulash on plates. His work wasn’t bad, it just all looked the same. It was like an oven in the gallery packed with goulash lovers. The women’s perfumes mingled with the men’s sweat to produce a noxious mixture. Brice went outside and leant against the wing of a yellow Fiat, sipping lukewarm rosé from a plastic cup. One by one, people left the gallery, dripping with sweat like survivors of some kind of shipwreck, the men loosening their ties and the women slipping a finger into their low necklines. A tall, rangy brunette whose hair was pinned up with a pencil came to sit next to him, fanning herself with her invitation.

‘It’s like a sauna in there!’

‘Unbearable.’

‘Did you like it?’

‘What?’

‘The show.’

‘Oh … In this heat I’m not overly keen on goulash.’

She laughed. A nose just sufficiently bent to miss perfection, dark eyes spangled with green, a perfectly ripe mouth, hardly any bust and unusually long, narrow feet which reminded him of pointed slippers.

‘Well, it’s given me an appetite. I could eat a raw elephant.’

‘Luckily I know a restaurant where that’s the speciality.’

She hesitated for a moment, dangling one of her mules from her toes, before turning to him with a serious expression. ‘Are you sure their elephants are fresh?’

‘I can guarantee it; they’re picked every morning.’

‘Good. Is it a long way?’

‘No, in Africa. There’s a bush-taxi rank on the corner.’

‘I’d prefer to take my car.’

‘Where is it?’

‘We’re sitting on it.’

The yellow Fiat took them to a pleasant restaurant in La Croix-Rousse, where, in the absence of elephants, they tucked into grilled king prawns under an arbour festooned with multicoloured lanterns. Once they had got the small talk out of the way, they spent a wonderful night in Emma’s bed. Three months later Brice Casadamont, illustrator, made Emma Loewen, journalist, his lawfully wedded wife at the town hall in Lyon’s sixth arrondissement. It was as simple as ABC. It was time. Puffed out from fast living, Brice was limping painfully towards his fifties, while Emma was frolicking through her thirties, as lithe as a gazelle. He spent months trying to understand how this young gilded adventurer could have fallen for an old creature like him. She was beautiful, healthy, passionate about her work, made more money than him – what did he have to offer her but memories of a time when perhaps he had been someone, and promises of a glorious future in which he had obviously long since stopped believing? But women’s hearts are as unfathomable and full of oddities as the bottom of their handbags. Occasionally he would ask her, ‘Why me, Emma?’ She would smile and, with a kiss, call him an old fool, pack her case and go off to report from Togo, or Tanzania, or somewhere else. At first, with every trip he was afraid he would never see her again but, strangely, she always came back. He had to get used to the idea that she loved him. This was their life, no matter that it raised a few eyebrows. She came and went. He stayed put, persisting in painting unsaleable canvases more out of habit than enjoyment, and earning derisory sums from illustrating deadly dull children’s books.

Once more the timer plunged him into darkness, but now that he was used to it, he nimbly dodged the obstacles. Giving up on the tin-opener, he got hold of a sharp knife and went back up to the kitchen.

It seemed to him that a hint of warmth was beginning to spread through the space. The radiators were tepid. That said, it would have been unwise to discard his reefer jacket and woolly hat just yet. After a battle with the tin of quenelles, a process in which he almost gashed his hand at least ten times, he ate dinner at the corner of the table, half listening to the news on France Inter. Bombs were going off almost everywhere in the world.

On the pretext of fighting the cold, but chiefly to take the edge off the emptiness surrounding him, he had finished the bottle of wine, and it was when his forehead touched the table that he took the wise decision to go to bed still fully dressed, rolled up in a dust cover the removal men had left behind. The church clock hammered eleven times, using his head as an anvil.

‘That’s not too hot, is it?’

‘No, it’s fine.’

Martine’s strong fingers were not only massaging his scalp, they were giving his brain a good kneading, and Brice was thoroughly enjoying it. The thousand and one domestic worries which had in recent days sprung forth from his skull like water through the holes in a colander were now merging into a soft paste not dissimilar to the origin of the world, when every embryo was unaware even of its own existence.

‘Right, if you’d like to follow me …’

He let himself be shown to the swivel chair and draped in a huge black nylon robe which completely obscured the lines of his body.

‘Short?’

‘Er … Yes, well, not too short.’

‘It’s strange. I feel I know you.’

‘But it’s the first time I’ve been here.’

‘Yes, you said. It must be from seeing all those faces go past. In the end they merge into one.’

He surrendered himself to Martine’s hands while his upturned eyes sneaked a good look at her in the mirror facing him. She had reached the age when a woman’s sugar turns to honey. An inviting bosom in a tight black T-shirt with a spangled Pierrot embroidered on it formed the base to a neckless doll-like face plastered with make-up which gave her plump cheeks the shiny satin look of artificial fruit. The features were brought to life by two obsidian pupils shaded by extravagant false lashes, with a piercing gaze that went straight to your wallet. Two-tone hair, platinum blonde and Day-Glo pink, crowned a forehead crossed by a worry line which no face cream could shift. A garlic-tinged accent emerged from lips picked out with a thick garnet line.

‘Well now, so you’re the one who’s taken the Loriol house?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s a beautiful house, and renovated top to bottom. I must say, a builder like Loriol knows how to go about it. And he’s a shrewd one, knows all the tricks. If you’d seen how it was before, a real wreck. I have to say, old Janin, the previous owner, was no good for anything after his wife died, let everything go to rack and ruin. He spent more time in the cellar than he did in the rest of the house, if you take my meaning. Poor old thing … Loriol must have got it for a song.’

The cellar. He had been down there for the first time the day before. A lovely vaulted cellar with walls covered in saltpetre and a trodden earth floor. He had stayed there for some time, sitting on a crate, looking at the double ceiling hook which in olden days had been used for hanging the pig. By concentrating hard enough he had ended up seeing the pig, head downwards, split open, offering up the unfathomable mystery of its entrails as in a Soutine painting. Seized by an irresistible force, he had grasped the iron hooks and, with knees bent, had swung there until his hands lost their grip. For three days he had been putting off the countless administrative procedures entailed by a house move: electricity, telephone, change of address, gas, water, bank … Normally it was Emma who took care of these chores. She would have had it all sorted in two shakes of a lamb’s tail, whereas he broke into a sweat, eyes watering, ears buzzing, if faced with the simplest form to fill in. No way out but to go and hang from a hookin a cellar ceiling. Old Janin must have felt this same deep distress after his wife died.

‘Did he hang himself?’

‘No, his liver gave out on him.’

‘Oh. What was his wife’s name?’

‘Marthe, I think.’

‘And were they very much in love?’

‘No, they used to row the whole time, but that’s normal. There you are, all nice and handsome.’

In the mirror Martine was holding up behind him, he noticed the skin on his neck reddened by shaving burn. The neck of a hanged man.

‘That’s perfect, thank you.’

A cloud of white hairs floated up round him as Martine relieved him of the robe.

‘You’ve a good type of hair, thick but slightly dry. I’ve a very effective lotion, if you’d like.’

‘Um, OK. Why not?’

Every time he got out of the hands of a hairdresser he was in such a vulnerable state that he could be sold anything at all, at no matter what price – something those seasoned professionals were not slow to sniff out and exploit.

While Brice was waiting for his change, a curious apparition made the little bell on the door ring.

‘Hello, Blanche. I’ll be right with you.’

Blanche lived up to her name, being dressed in white from the toes of her shoes right up to her strange crocheted lace cap which reminded him of a tea cosy. All in white, but an off-white bordering on old ivory. She was like a bride who had been in the shop window for too long. It was difficult to put an exact age on her; she could have been anywhere between sixteen and sixty, depending on whether you looked at her eyes, which were like those of a timid child, or her hands, gloved in skin like puckered silk.

Instead of making a beeline for the dog-eared magazines littering the coffee table, as any other female client would, she stayed standing, twisting a little purse embroidered with pearl beads in her impossibly delicate fingers. Her eyes were fixed on Brice. It made him vaguely uneasy.

‘So, Monsieur. Welcome to Saint-Joseph!’

Outside, the north wind grabbed the back of his neck with its icy fingers. Through the curtain veiling the window, he saw Martine take Blanche by the arm and lead her gently to the washbasin, where she sat down, leaning back so abruptly that it looked as if an invisible hand had just snapped her in two. On his way from the hair salon to the post office he could not rid himself of that immaculate vision imprinted like a negative on his retina.

In the post office, three elderly ladies were waiting at the counter – one big, one middle-sized and one small, all so alike it was tempting to think of slipping them one inside the other like Russian dolls. The saving in space would have been advantageous as the place was minuscule. Four customers was definitely one too many. Brice squeezed himself up against the wall as best he could, between a missing persons notice depicting a curly-headed cherub and an advertisement for a loan with unbeatable rates. One after the other, each babushka exchanged with the postmistress news of their respective states of health. The talk was of hernia bandages, support stockings, varicose veins, rheumatism, prolapses, and other of life’s small mishaps, punctuated by the sound of documents being stamped, and this for a good half-hour. At last it was his turn. Not yet on sufficiently intimate terms with the postmistress to mention the ravages wrought by time on his own body, he confined himself to asking for a packet of cards, intended to inform people of his change of address. Éliette (that was the postmistress’s sweet name) had the ashen complexion of a consumptive heroine. No doubt her screen was not up to the job of protecting her from her customers’ germ-ridden breath. She broke into a wan smile as she handed him a bundle of cards and, raising an eyelid like a withered iris petal, turned a watery gaze towards him.

‘Are you the gentleman who’s taken over the Loriol house?’

‘Yes, that’s me.’

‘Do you have relatives here?’

‘But … No … Why?’

‘You look like a gentleman who used to live here. The family goes back generations. Welcome to Saint-Joseph, then.’

He thought he detected a touch of irony in the little phrase which she breathed out like a last sigh.

The days went by, or was it perhaps the same one again and again? Other than a minimum of maintenance – eating, drinking, sleeping – which necessitated brief commando raids on the supermarket, Brice did nothing. Not once had he gone up to the studio, nor into the other rooms, for that matter. He had adopted the stance of the monitor lizard: total immobility, eyelids half closed, prepared to wait for centuries for its prey – that is, a sign from Emma – to come along. He was becoming inured to boredom as others are to opium. Elbows on the table littered with dirty plates and cutlery, the remains of charcuterie in greasy paper, and wine glasses with a coating of red, he would leaf through his address book, yawning. Except for a few professional connections useful to his survival, he saw no one he should inform of his new contact details. Acquaintances, he had those, of course, but friends? They all seemed to belong to a bygone world, for which he no longer felt the slightest nostalgia. Under each of the names he scored through in red, a face would dissolve, its blurred outlines overflowing the page and calling to mind only faint, drowned continents. He experienced neither remorse nor regret. They had had their time. He had new friends now, called Martine, Blanche, Éliette, Babushka. Only women. Obviously, since in the daytime the village was transformed into a no man’s land. From dawn to dusk the able-bodied men were engaged in obscure and mysterious occupations. Occasionally you might come across an old man on a rickety bicycle in a back street, carrying a crate of cabbages or leeks. Otherwise it was women, nothing but women. Practical, solid women, women you could rely on, with short hair and loose-fitting clothes. In the mornings they would walk the children to school, picking up bread and the newspaper, exchanging two or three pieces of gossip before hurrying off to their respective homes to get on with the countless chores in house or garden which would keep them busy until evening. What might the inner lives of these housewives be like? By what dreams were they haunted? What secrets were they hiding?

Brice was at that point in his reflections when a loose slip of paper drifted out of his address book. He recognised Emma’s rounded handwriting. She had made a note of the various places she wanted to put up shelves. It was ridiculous how fond women were of shelves. All those he had known had made him put them up when they moved in. It had to be some sort of initiation rite. To be honest, he had never really been excited by that sort of activity, but anything to drag himself out of the dull apathy into which his lunch of tripe à la Provençale had plunged him. It was time to take some measurements, he told himself, braving the garage in search of a tape measure.

Currently the garage looked like nothing on earth. It was as if some sort of typhoon had laid waste the pyramids of boxes built with such care by the removal men. Odd items of clothing flopped like stranded seaweed over piles of crockery, books fanning open, and scattered CDs, which he had to pick his way over like a heron. The wreck resulted from the simple fact that, in order to lay your hands on some vital object (which very often was still not found), it was necessary to fight your way through a mountain of this, that and the other with an energy born of desperation. If the first few boxes had been meticulously packed and labelled, most of the others, marked ‘Misc.’, simply contained a jumble of things he had no idea even existed. And the more of them he uncovered, the more the confusion grew, until it was no longer possible to tell one thing from another. Only chance could be of any help. And it was thanks to chance that he came upon his DIY kit, after he had toppled a shoebox which hit the floor, pouring out a stream of seashells. He crushed some in regaining his balance, and set about making an inventory of his tools: one hammer minus its shaft, one twisted screwdriver, two baby-food jars (spinach and ham, apple and pear) half full of nails, screws, drawing pins, rubber bands and wall plugs, a Stanley knife without a blade, a gummed-up paint brush, rusty pincers, a ball of string, a roll of sticky tape, two jam-jar lids and, yes, a flexible steel rule, one of those that joiners carry proudly in the special little pocket on the right leg of their overalls. In view of the overwhelming task Emma had entrusted to him, these materials were clearly insufficient. For an hour he sat in the dark, bursting countless blisters of bubble wrap, unable to convince himself of the necessity of a sortie to the nearest Bricorama. DIY superstores were beyond the pale to him, as much a no-go area as a locker room. In any case, if he did have to steel himself to it, it was too late for today. That kind of expedition was undertaken in the early morning, like hunting or fishing. Anyway, he didn’t feel prepared – he had to make a list, take measurements. That was it, first the measurements!

Armed with the steel rule, he began measuring anything and everything, the width of doors, the length of handles, his left forearm, the wingspan of a beetle squashed at the bottom of the sink that morning, the height of the sink, the depth of a box of camembert, and its diameter. And so on until late into the night, when he finally stopped, worn out, but dazzled at knowing the dimensions of his universe down to the last millimetre. It was then that he remembered all the catalogues and brochures which cluttered up his letter box every morning. Screw-It-All, DIY Super-Something – the bin was stuffed full of them. He ran to get them and began poring over them compulsively until dawn, when sleep carried him off to a universe inhabited by 2,000-watt blowtorches, tilting jigsaws, orbital sanders with dust bags and large-sized sanding sheets.

The timbre of the church bell varied, depending on the wind. It ranged from the whine of an electric saw to the radiating waves of a gong. Thus it not only told the time, but what kind of day it was. Today was a gong day, with a heavy bronze sky that weighed down on you. Brice had indeed gone to Brico-whatsit as planned, but once he had parked in the car park and seen the never-ending coming and going of the half-man, half-bear creatures shifting heavy loads – wooden beams, metal rails, bags of cement, oil cans – he was gripped by a kind of terror which paralysed him for a good fifteen minutes. It brought back memories of military service, or the area around a stadium, or anywhere men were all together. He refused to turn back, however, and, in awkward imitation of the lumbering gait of a man who knows what he has to do, he ventured head down into the store.

They had thought of everything here. There were all sorts of screws, hammers to drive nails into corners, saws for cutting on the diagonal, glues for sticking anything to everything, spiral staircases that could be put up in ten seconds, paints to hide every sin, real wood, fake wood, marvellous tools for weird and wonderful purposes, and all of them beautiful, red, yellow, green and chrome, like Christmas toys. Brice had no idea what to choose. He went for a five-kilo sledgehammer on sale for next to nothing. It was the first time he had bought a five-kilo sledgehammer. He was more than a little proud. Emma would certainly have approved of his purchase.

Nothing is as soothing as watching a saucepan of water come to the boil. Brice had just plunged two eggs into the merrily moving bubbles when the phone rang for the first time since he had lived there. The sound was so incongruous that he reacted only at the fourth ring. The girl on the line was nervously offering him a wonderful fitted kitchen. Brice declined, and thanked her. No sooner had he hung up than the phone was gripped anew by the same noisy fever, making the house tremble from cellar to attic.

‘Hello, is that Brice?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s Myriam. How are you?’

That was quite a question his mother-in-law had landed on him.

‘Oh, fine, fine.’

‘You’re sure?’

‘Well, you know, when you’ve just moved into a new house it’s always a little …’

‘Oh, I quite understand. You know, Simon and I are thinking of you.’

‘That’s kind.’

‘It’s all so … so … We were thinking of dropping by this weekend.’

‘Oh, I’d love that, but the house isn’t ready yet. There’s still a lot to do and …’

‘Exactly. We could give you a hand. You know how keen on DIY Simon is. And I’m sure you could use a woman for your washing and cooking. We all know what a man on his own is like.’

‘Honestly, I’m managing very well. I’m just putting up some shelves. Emma would be cross to think I’d entertained you in a building site. I’ve no wish to get told off when she comes back.’

‘Brice.’

‘Yes?’

‘Are you still taking the medication Dr Boaert prescribed?’

‘Of course.’

‘Brice … you need help. You know quite well we’re going through the same as you. You mustn’t let yourself go. We’ll be stronger, the three of us together. I’m sure Emma would have agreed with me. Brice?’

Silence.

‘Brice, are you listening to me?’

‘Yes, Myriam. I’m sorry but I have some eggs on the stove. I’ll have to hang up now.’

‘Think about what I’m saying, Brice. We’re very fond of you.’

‘Me too, Myriam. Give Simon a hug from me. Thanks. I’ll call you soon!’

He threw down the receiver as if it were a dead animal and unplugged the cord.

Emma’s picture joined the other photos scattered at his feet like a game of solitaire sprinkled with egg shells. He felt a heaviness in his stomach and stretched out on the camp bed he had set up just beside the boiler. If the truth be known, apart from the kitchen, toilet and bathroom, he scarcely went into the other rooms any more. What was the use of making hundreds of trips to and fro in order to distribute all these things, when he knew that Emma would rearrange them all when she got back? It was easier to settle down in their midst. The icy glow of the fluorescent light, whose timer switch he had craftily deactivated with a piece of sticky tape, didn’t bother him in the least, day or night. A kind of trench dug through the bric-a-brac allowed him to reach the staircase. It was enough. Thanks to this makeshift arrangement, he had everything within reach. This set-up was so much more practical, and it was obvious the objects had accepted him as one of their own.

That morning in the post, among a pile of brochures advertising monster sales with prices cut, slashed, pared to the bone, there had been a letter from his editor who, while sympathising deeply with his situation, informed him of the urgent need to submit the final drawings for Sabine Does Something Silly. He would be eternally grateful if Brice could deliver them within a week.

Brice could no longer bear the little girl, still less her creator, Mabel Hirsch. Admittedly the two of them had been his bread and butter for a number of years now, but after about ten volumes he had had enough: Sabine Loses Her Dog, Sabine Takes on Dracula, Sabine Sets Sail, Sabine … The little brat, whose face he riddled with freckles for sport, was seriously taking over his life. As for her creator, he must have killed her at least a hundred times in the course of troubled dreams. He would throttle her until her big frogspawn eyes burst out of their sockets and then tear off all her jewellery. She could no longer move her poor arthritic fingers, they were so weighed down with gold and diamonds. Strings of pearls disappeared into the soft fleshy folds of her double chin. Old, ugly and nasty with it! All that emerged from her scar of a mouth, slathered in blood-red honey, were barbed compliments which wound themselves round your neck, the better to jab you in the back. The widow of a senior civil servant, she had never had to earn a living. Yet she was one of the publishing house’s top sellers. Dominique Porte, the director, put up with the worst humiliations from her, and consequently so did Brice. How many times had she made him do the same illustration over and over again, only to come back to the first one in the end? And yet, according to what she told anyone who would listen, she adored him. That was perhaps true in a sense, for they both had a hatred of childhood, only for different reasons. She had probably never experienced it, while Brice had still not succeeded in leaving it behind.

In the early days of his marriage to Emma, friends had warned him, ‘She’s thirty, she’ll be wanting to make a father out of you!’ They were wrong. He and Emma had barely so much as touched on the subject. Emma had nothing against children – other people’s, that is. When they visited friends who had children, she showed affectionate interest, never appearing to tire of playing silly games with them, but when it was time to go, no sooner had the car moved off than she gave a sigh of relief.

Her friends and family were astonished by this state of affairs. To them it seemed abnormal that any perfectly healthy young woman should not wish to play mummy. Perhaps it was because of her career, having to jet off on trips at a moment’s notice, or perhaps one of the two was sterile. Brice and Emma laughed it off, content to leave their secret veiled by an artistic blur. The truth was so much simpler than that. Their love bound them together so closely that the smallest seed, the tiniest embryo would have come between them.

Children had always frightened him, even when he was one himself. Those signs on the way into villages: ‘Beware Children!’ How were they to be interpreted? He feared them like the plague.

‘Children are ogres, vampires. You only have to look at their young parents – the mothers with their dried-up breasts, the empty-handed fathers – to grasp the sheer greed of these merciless cannibals. They get us in the prime of life and ruin our secret gardens with their red tricycles and bouncy balls that flatten everything like wrecking balls. They transform our lovers into fat women, drooling blissfully as they feel their bellies, and turn us into idiots numb with exhaustion, pushing supermarket trolleys overflowing with bland foodstuffs. They get angry with us because they’re midgets, obliging us to punish them and then regret it. On the beach they play at burying us or dig holes to push us into. That’s all they dream of: taking our place. They’re ashamed of us, are sorry they’re not orphans, but still ape us horribly. Later they ransack our drawers, and become more and more stupid as their beards grow, their breasts grow, their teeth grow. Soon, like past years, we no longer see them. They’ll reappear only to chuck a handful of earth or a withered rose on to our coffin and argue over the leftovers. Children are Nazis; they recognise only one race: their own.’

The editor’s letter came to rest on a pile of envelopes he had not bothered to open. He stretched out on his camp bed and said to himself that this would be a good day to die.

He was drowsing, drowsing, and then, quite without warning, he opened his eyes and woke up as someone different, someone who was having nothing more to do with Sabine, in this life or the next. It had just struck four, and it was still light. The hard-boiled eggs still lay heavy in his stomach and so it occurred to him to aid his digestion by going for a short walk in the open air for the first time since he had arrived. The choice on leaving his place was simple: either you went left and after 500 metres you hit the main road, where the terrifying articulated lorries would be more than happy to flatten a pedestrian, or you went right, taking the path that wound past the church, up among the vines. Naturally, that was the one he took, whistling to himself. Not for long. The section leading out of the village presented no problems, but very soon the slope became so steep it felt like scaling a vertical wall. His smart tan suede loafers were far from suited to this kind of terrain, muddy, full of pebbles and deep cracks. Every other step he stumbled, tripped and slid, enjoying none of the benefits of nature. He had to sit down to remove a stone from his left shoe. Vine stalks, twisted like the hoofs of a sick billy goat, clung to grey wooden posts; banks of brambles coiled beside the path like barbed wire; straggly trees pleaded with the sky, an occasional mocking crow perched on a branch; and the worst of it was this bitch of a red, slippery soil. There was nothing to stop him turning back except men’s obstinate need to see things through to the very end. He set off again, sliding on this Way of the Cross with no station at which to get off.

A quarter of an hour later, exhausted and covered in mud, just as he was extracting a crown of thorns’ worth of spines from his palm, he heard the sound of a spring on his left. It was coming from a sort of gap in the undergrowth. Drawn on, as in a fairy tale, he ventured in. Despite the pitfalls, treacherous roots, half-buried stones, holes and mounds, nothing on earth could now have prevented him from getting closer to this primal gurgling; it had become as essential to him as a teat to a newborn baby. It was as he came round the final turn that he caught sight of it, new, exposed, gushing forth from the granite lips. The water, thick like a cordial, greasy like oil, flung the sky’s image back at it in a magnificent act of defiance.

From pool to pool it seethed, leaped, splashed the mineral formations, proud in its opulence, intoxicated with bubbles, furious, foaming. His eyes filled with tears. Deafened by the tumult of the ceaselessly roaring torrent, he moved forward cautiously on to the slippery rock in the slim hope of weighing the emerald liquid in his hand. Hold water! Pathetic scrap of a man. No sooner had he skimmed it with his fingertips than he lost his footing. Then it was coming down on him with its full weight, sweeping him along in its depths with bursts of laughter. Gasping as the cold bit, Brice struggled against the current, but it was so strong that after a few seconds he gave up the fight. He felt strangely relieved, as if he had been waiting for this moment since birth. He was tired of fighting, tired of facing up. Perhaps this was where Emma was waiting for him. He needed only to let himself go. In a whirlpool his foot hit a stone and pain ripped him out of the kind of torpor in which he was sinking. His hand shot out of the foam and clutched a root.

Crouching on the corner of a rock, shaking, stupefied, he watched his hat swirling away to vanish on the glistening back of a waterfall, whose thundering waters plummeted a good ten metres on to jagged rocks beneath.

Shamefaced, teeth chattering, he limped back towards the village.

Luckily the chemist’s shop was still open. Its green cross shone out against the rust-coloured sky. The pharmacist was busy attending to a customer. Taking in his pitiful state with one glance, she slipped out from behind the counter and rushed over to Brice.

‘What on earth’s happened to you, you poor man?’

‘I fell, up by the spring. I must have sprained something.’

‘I’ll just finish serving this customer and I’ll be right with you.’

Her gentle smile warmed his heart. He would have quite liked to call her ‘Maman’. The pharmacy smelled clean, of toothpaste and safety. With a sigh of relief, he stretched out his injured leg. The customer in question was none other than the strange girl he had met at Martine’s hair salon.

‘This is the last time, Blanche. You must go back to the doctor’s. I can’t give you any more of your medication if you don’t have a prescription. Do you understand?’

‘Yes. Two packets.’

‘No, Blanche. One, and then you come back with a prescription.’

‘All right, one.’

Blanche’s voice was, well, colourless, a wisp of a voice, barely audible, as if a ventriloquist were making her speak. As she was about to leave, she froze in front of Brice.

‘What a waste of time.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘I waited and waited.’

‘You must be mistaken, I—’

‘Come now, that’s not kind. I’ve been worried. Well …’

She pursed her lips and shrugged, fiddling nervously with her little pearly purse. White stockings, white coat, white hat, white gloves. Only her eyes were black, as black as coal, almost aglow. Whipping a card from her pocket, she held it out with a feverish hand.

‘Tomorrow, five o’clock, for tea.’

Without waiting for him to reply, she left the chemist’s, as stiffly as a wooden soldier. The pharmacist crouched down in front of him. The gaping neck of her overall revealed two huge breasts, like the smooth rocks forming the mouth of the spring.

‘That’s quite a sprain you have there. I’ll put some ointment on and bandage it, but perhaps you should have it X-rayed as well.’

‘All right. Tell me, who was that, the white lady?’

‘Ah. Blanche Montéléger, from the big house on the edge of the village. She’s a little … eccentric. I thought you knew each other.’

‘No.’

‘It’s just that you look so much like her late father. I’m not hurting you, I hope?’

‘No, not at all.’

The card was not printed but handwritten in curly old-fashioned script. No address or phone number, just Blanche Montéléger.

Emma and Brice had been arguing non-stop since the moment they woke up, about everything and, especially, about nothing. It was the first time this had happened to them and neither knew the reason for it now. Maybe it was because of the storm which was circling over the city without ever getting round to breaking. Every object seemed to be charged with electricity and made their hair stand on end as soon as they touched it.

‘I’ve told you a hundred times to put the bread away in the basket. It dries out and gets thrown away, and I hate waste.’

‘And you might change the toilet roll instead of leaving half a sheet.’

‘The way you slam doors!’

‘Could you turn the sound down? It’s unbearable!’

Once they had exhausted their whole stock of petty comments, each of them retreated into a stubborn silence which only increased their sense of unease. They paced around the flat like clockwork figures, brushing past each other in the corridors, avoiding looking at each other, ashamed, aware of the ridiculousness of the situation but unable to act normally. It was as if they had been replaced by grotesque doubles. It was a very difficult day, damp with sorrow, clouded by doubt, with that panicky fear of a child who has let go of its mother’s hand. In the evening, when the storm finally broke, they fell into each other’s arms. It had happened only once in ten years of marriage and yet this was the day he now found himself missing. How he would have loved to relive it, ten, a hundred, a thousand times!

Rolled up in his filthy sleeping bag on the creaky camp bed, amid the horrendous tip the garage had become, Brice felt like a boxer alone in the ring, up against himself. He needed to hit something, it didn’t matter what. In spite of his swollen ankle he grabbed the five-kilo sledgehammer and headed for the kitchen. Emma had intended knocking down the wall between it and the dining room to make a kitchen-diner – far more sociable, she thought.

With the first blow, he felt as if the whole house were buckling at the knees and groaning, like an ox under the slaughterman’s hammer. The impact reverberated through the shaft of the sledgehammer before spreading through him from head to foot. The vibrations went on for a good ten seconds. In the sink, a stack of plates collapsed. Horrified, he took in the terrible wound he had inflicted on the wall. Beneath the fragments of plaster, the pink flesh of the brick was visible and a long fissure ran from ceiling to floor. He had struck as hard as he could but the poor old wall was still standing. He had to finish it off. He gritted his teeth, closed his eyes and began pounding with all his might like a madman until, having hit empty space, carried along by the momentum of the tool, he circled on the spot like a hammer-thrower before collapsing on to the heap of rubble, wild-eyed and dazed. His ankle was swollen to twice its size. Plaster dust was gathering in his nose, making him want to throw up like after the first line of heroin. Without meaning to, he had created an almost perfectly circular hole through which the dining-room table and chairs could be seen, stock still and startled, like a flock whose rumination has been interrupted by a passing tourist. It was the first time he had knocked down a wall. His first wall … He didn’t know whether he should feel proud or sorry. He was tempted to turn himself in to the police. The house was sulking. Not one window would look him in the face.