Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Gallic Noir

- Sprache: Englisch

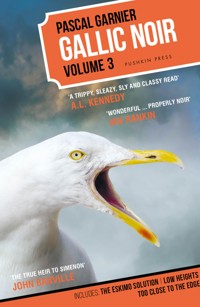

Written over a 15-year period from the mid '90s, Garnier's short novels weave a profound and darkly comic tapestry of human experience. Volume 3 includes The Eskimo Solution, which combines the story of a struggling writer with excerpts of the crime novel he's writing, which will spill over into his own life; Low Heights, in which a cantankerous retiree falls for his nurse and finds himself confronted with a man claiming to be his long-lost son ... but the family reunion is threatened by the vultures circling above; and Too Close to the Edge, the tale of a quiet retirement in the foothills of the Alps turned upside down.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 542

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Pascal Garnier

Pascal Garnier was born in Paris in 1949. The prize-winning author of more than sixty books, he remains a leading figure in contemporary French literature, in the tradition of Georges Simenon. He died in 2010.

Emily Boyce

Emily Boyce is in-house translator and editor at Gallic Books.

Jane Aitken

Jane Aitken is a publisher and translator.

Melanie Florence

Melanie Florence teaches at the University of Oxford and translates from the French.

‘Wonderful … Properly noir’ Ian Rankin

‘Garnier plunges you into a bizarre, overheated world, seething death, writing, fictions and philosophy. He’s a trippy, sleazy, sly and classy read’ A. L. Kennedy

‘Horribly funny … appalling and bracing in equal measure. Masterful’ John Banville

‘Ennui, dislocation, alienation, estrangement – these are the colours on Garnier’s palette. His books are out there on their own: short, jagged and exhilarating’ Stanley Donwood

‘The combination of sudden violence, surreal touches and bone-dry humour have led to Garnier’s work being compared with the films of Tarantino and the Coen brothers’ Sunday Times

‘Deliciously dark … painfully funny’ New York Times

‘A mixture of Albert Camus and JG Ballard’ Financial Times

‘A brilliant exercise in grim and gripping irony; makes you grin as well as wince’ Sunday Telegraph

‘A master of the surreal noir thriller – Luis Buñuel meets Georges Simenon’ Times Literary Supplement

‘Tense, strange, disconcerting and slyly funny’ Sunday Times

‘Combines a sense of the surreal with a ruthless wit’ The Observer

‘Devastating and brilliant’ Sunday Times

‘Bleak, often funny and never predictable’ The Observer

The Eskimo Solution

Low Heights

Too Close to the Edge

Pascal Garnier

Pushkin Vertigo

A Gallic Book

The Eskimo Solution

First published in France as La Solution Esquimau by Zulma

© Zulma, 2006

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Gallic Books

Low Heights

First published in France as Les Hauts du Bas by Zulma

© Zulma, 2003

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2017

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Gallic Books

Too Close to the Edge

First published in France as Trop près du bord by Zulma

© Zulma, 2010

English translation copyright © Gallic Books, 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Gallic Books

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-805336-05-1

Typeset in Fournier MT by Gallic Books

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

The Eskimo Solution

Low Heights

Too Close to the Edge

The Eskimo Solution

1

Louis had slept on the bottom bunk in the children’s room. He was surrounded by soft-toy monsters and a fire engine dug into his back. Somewhere outside a drill ripped into a pavement; it must be daytime. Louis turned over and curled up, knees under his chin, hands between his thighs, nose squashed under a downy pink dinosaur smelling of dribble and curdled milk.

Why had they rowed the previous evening? … Oh, yes! It was because Alice wanted to be cremated whilst he wanted to be buried. For Alice, with her straightforward common sense, it was crystal clear. First of all, cremation was less expensive; secondly, it was cleaner; thirdly, it avoided uselessly occupying ground (think what could be built instead of the Thiais cemetery, for example!); and fourthly, her somewhat romantic conclusion was that she would like her ashes to be scattered off the coast of Kalymnos (where they had spent their last holiday) from the bow of a beautiful white boat.

He had interrupted her a bit abruptly. First of all, when you’re dead you don’t give a flying fuck about the burial costs; secondly, we already tip enough muck into the sea; thirdly, cemeteries are much more pleasant to wander through than dormitory towns; and fourthly, given the progress of science, it’s entirely possible that one day we’ll be able to recreate life from skeletons, whereas a handful of ashes thrown in the sea, well … He’d accompanied the last point with an obscene gesture.

And who was going to pay for his fucking burial? Was it not enough that he sponged off everyone while he was alive, did it have to continue after his death? Such egotism! Would he like chrysanthemums every Hallowe’en as well?

Of course he wanted chrysanthemums! And trees filled with birds, and cats everywhere! Wasn’t she the one who went into raptures over the mossy old gravestones in the Père-Lachaise? That one where the stone had split under pressure from a growing laurel tree?

OK, so why didn’t he put money aside to pay for his old moss-covered gravestone? Why was that, then?

Here we go, money, it’s always about money …

After that all he remembered was a sordid slide into a petty domestic squabble and the harsh realities backed up with numbers that she threw in his face. He didn’t have the ammunition to argue with Alice about money, so he had risen from the table, saying, ‘If that’s the way you feel, I just won’t die. That’ll be cheaper, won’t it?’

And that was really what he had in mind. It was a conviction rooted deep inside him: he would never die.

But that certainty had been severely shaken this year; four of his friends had died. Obviously, as he was forty, he had encountered death before, but this was different. Before it had always either been old people – an uncle, an aunt – or acquaintances who weren’t expected to live long, or if they were young, accidents, mostly car accidents, and the deaths seemed normal. But the last four had been people like him, going to all the same kinds of places, enjoying the same books, music and films. Their deaths had not been sudden; they had had time to get used to the idea, living with it for months, discussing it calmly, as you might discuss money problems, work problems or problems in your relationship. And it was that attitude of rational acceptance that had thrown Louis. People like him (not exactly like him now they were dead) had accepted the unacceptable. Four in one year.

As for the others …

Every day at the same time I go up to my study, read over these pages and ask myself, ‘What’s the point of writing a story I already know off by heart?’ I’ve explained it to so many people that the tiresome formality of putting it down on paper is about as exciting to me as opening the TV guide to discover The Longest Day showing on every channel. In an ideal world I’d sell the story as it is, in its raw state, to someone who had some enthusiasm for writing it. Or who didn’t, but would write it for me all the same. Not that it’s a bad story, far from it. Madame Beck, my editor, is the only one to have expressed any reservations. I had a hell of a time winning her over.

‘It’s the story of a man in his forties called Louis, who’s a nice guy but skint, and kills his mother for the inheritance.’

Madame Beck’s harsh-sounding name suits her down to the ground. After a long, sharp intake of breath, she replied.

‘Not exactly original.’

‘Wait a minute, let me go on. It’s a very modest inheritance – but that’s beside the point. Since everything goes to plan, no trouble with the law or anything, he starts killing the parents of friends in need. Of course, he doesn’t tell them what he’s doing – it’s his little secret, pure charity. He’s an anonymous benefactor, if you like.’

Madame Beck lowered her head in despair.

‘Why don’t you carry on writing for children? Your kids’ books are doing well …’

‘This is a kids’ book! He’s a really nice guy! He loves his mother, loves his friends, his friends’ parents, he loves everyone, but these are tough times for all of us, aren’t they? He kills people’s parents the way Eskimos leave their elders on a patch of ice because … it’s natural, ecologically sound, a lot more humane and far more economical than endlessly prolonging their suffering in a dismal nursing home. Besides, he’ll hardly be doing them harm; he’ll do the job carefully, every crime professionally planned and tailored to the person like a Club Med holiday. Plus there’s nothing to stop us giving him his comeuppance at the end. I could have him murdered by the twenty-something son he hasn’t seen for years, who’s got in with a bad crowd. Or have him fall prey to a random act of violence, a mugging on the métro gone wrong, something like that … What do you think?’

Two hours later, Madame Beck was reluctantly handing me a cheque, barely able to look at me.

With that meagre advance, I’ve been able to rent a cottage by the sea from a painter friend of mine, where I’ve spent the past two months yawning so hard I’ve almost dislocated my jaw.

‘I wake up in the morning with my mouth wide open. My teeth are oily: I’d be better off brushing them before bed, but I can never bring myself to do it.’ These words of Emmanuel Bove’s, the opening line of his novel My Friends, sum up my state of mind exactly. I put aside my typewriter – already thick with dust – and tackle tasks more suited to my skills: washing up, a bit of housework, starting a shopping list, bread, ham, butter, eggs … I don’t mind chores; they stop me beating a permanent retreat to my bed. Plus, routines are a useful way of preparing for the hereafter. Then I head to the beach, whatever the weather.

Today, it’s glorious, a picture-postcard sky, framed by the inevitable seagulls. The beach is very close to where I’m staying – a five-minute walk straight down Rue de la Mer. It’s always a surprise to see that mass of green jelly at the end of the road and the no-entry sign sticking up like a big fat lollipop on the horizon. You find yourself leaning forward as you walk, head down against the wind that stands guard along the front. There’s something minty about the cold. You can clearly see the chimneys of Le Havre and the tankers waiting their turn at Passage d’Entifer.

When you are mute, or almost mute, certain words explode inside your head like fireworks: ENTIFER. Or even: TOOTHBRUSH. I never speak to anyone, only the woman in the tobacconist’s on Rue de la Mer.

‘Good morning, Madame … How are you today, Madame?’

Like the sea, she’s up and down – she lives above her shop and is never seen anywhere else.

There are two people on the beach. As they approach the waves, they stop and ponder whether to turn left or right. In the end they part ways, one sticking out her chest and grabbing an armful of sunshine, the other spinning on the spot, flapping the wings of her coat. She stumbles into the foam and re-emerges, knees held high. I can put up with happy people, from a distance.

I never walk far along the beach.

Yes, when I was first here, I went exploring, clambering over rocks and craggy outcrops, coming back exhausted, my pockets filled with pebbles, shells, bits of wood. Now I prefer to sit on the bench for old people. There are none of them here at this time of year – it’s too cold. For a brief moment, I enjoy the exhilarating feeling of being right where I should be, a feeling made all the sweeter by my knowing exactly where I’m headed: back to humanity with a thud.

Here comes the ‘thug’! I know him by his lumbering gait; he walks as if pushing an invisible wheelbarrow. Shaved head, face like a suitcase that’s been dragged around the world, hands like feet and feet that make furrows in the ground, whether sand, concrete or tarmac. The man has a permanent black eye or a hand in plaster – they say he’s always getting into fights. And yet everyone accepts him, puts up with him. I, on the other hand, am terrified of him. If it was up to me, he’d have been locked up long ago, or simply eliminated. He forces me to get up and walk further. But further is too far for me. I decide to head back along the beach.

I love trampling on shells; I imagine they’re my editor’s glasses. There’s no one left now that the two people have gone, and the thug with them. I suddenly feel so alone it’s as if I’m invisible. The sky shrinks back above my head like burnt skin. The silence bores into my ears. I’d give anything to be anywhere but here.

As for the others (the ones who weren’t dead, not yet) they were like him, living flat on their stomachs in hastily built trenches, keeping watch for the snipers that were decimating their ranks. Reaching their forties was starting to feel like the path to the emergency exit.

Louis would happily spend the day in the children’s room, crammed into the little bed like a vegetable in a crate. When he was little, he used to spend hours like that, in a state of boredom. No one should believe that good children sitting quietly are gentle dreamers, inhabiting marvellous worlds. No, they’re just bored. Although the boredom of childhood is of a different quality, a sort of opium. Later on, it’s hard to recall that feeling. Tedium has replaced boredom. The row with Alice yesterday evening, or rather its consequences, were part of the tedium.

Suddenly the little room was suffocating; the pleasant gloom had become a black cocoon pressing in on him. Louis jumped out of bed, pulled back the curtains and opened the window. He was hit by the light and the hammering of the pneumatic drill. He closed his eyes, grimacing, and staggered back to the little bed. There was a note stuck under the bedside lamp. Alice’s writing.

‘If you could be gone by the time I get back, that would be good.’

Of course, he had been expecting this for a long time, but why now? That stupid argument must have been the last straw. As if he cared what happened to him after his death! Now he was going to have to move out.

The impact of the sparrow against the glass of the half-open window made no more noise than a rubber ball bouncing on a carpet. Yet this little collision radiated like an electric charge through Louis from his chest to his groin. All his childhood fears were contained in that little ball of grey feathers, tiny bones and quivering flesh now trapped inside the room by the curtain. Outside, the insistent thrumming of the drill was the counterpoint to the noise of the bird’s panicked beak against the window.

‘Go away!’

The bird froze in front of the window, framed by the white sky like a bad painting. Louis closed his eyes, hoping the sparrow would escape by itself, but the tapping of the beak started up again, shattering the silence. All he needed to do was lift the curtain and open the window wide but Louis could not bear the idea of even the briefest physical contact with the idiot bird. He would need a long stick, a fishing rod, for example. What if the bird, in freeing itself, flew into his face? Birds always got in your face, like cats and spider webs.

A breath of air briefly lifted the white net curtain. Enough to allow the sparrow to propel itself through the beckoning gap. But it was a very young bird, to whom no one had ever explained the difference between inside and outside. And so instead of flying off it began to twirl about like a demented wind-up toy between the four walls of the little bedroom. Exhausted and terrorised, it came to rest wide-eyed on the corner of the wardrobe. The smell of fear turned the atmosphere of the room into a toxic, unbreathable acid. Then another draught arrived to waft the curtain. The bird spotted the white rectangle and recognised its territory, the great outdoors with no corners and no obstacles that stretched from never to nowhere. Ecstatic, it flung itself at the opening. It was halfway out when the window banged shut, cleaving it in two.

Open-mouthed, Louis watched as grey feathers floated to the carpet. Just then the phone rang.

‘Hello? Yes, it’s me. Good morning, Richard. No, I haven’t forgotten I owe you money. Yes, I know, but … everything’s a bit tight at the moment … Listen, Richard, I can’t talk to you now, a bird has just been decapitated in front of me … No, it’s not another of my excuses! I swear, it’s shaken me up. Why don’t we get together later, shall we say 12.30? … Where? Brasserie Printemps, under the dome … And why not? … Yes, yes, I insist, it’s a beautiful place. Excellent, see you soon.’

Why did I call him Louis? After the old French coin, because of his money worries? I must have been pissed when I came up with that. I get silly when I’ve had a drink, start playing around with words. Louis doesn’t suit him. He needs a younger, more contemporary name. Like the guy at the other end of the bar, for example – what’s his name? … I can hear it from the mouth of the landlord serving him: Jean-Yves. I can’t imagine calling my hero Jean-Yves for 200 pages.

Though I can’t claim to have done much to serve the greater good today, I’m still feeling quite pleased with my efforts. My word count is hardly spectacular, but it’s not a bad show for two hours’ work. The bird incident was what got me back in the swing of it. When I opened my eyes this morning, I noticed that one of the panes in my bedroom window was broken and a fluffy white feather was caught in the Z-shaped crack. I don’t remember hearing anything, but I’m sleeping deeply at the moment. Whatever it was, it could only be a sign, an invitation to pick up my quill. I could have written more but Hélène rang. Wants to take me on a three-day trip to England. I’ll be glad to see Hélène, but why England? What’s wrong with meeting up here?

After the phone call, I went back to the beach to watch the sun go down. The footprints in the sand are an odd reminder of all the people who’ve pounded up and down the beach, whom you’ll never see. The sun was taking for ever to disappear, so I left before the show was over. On the way home, I stopped at a café for a half. I wasn’t thirsty; I just needed some human company, to nestle among the other beasts in the stable. Plenty of people go out in their slippers here. The guy next to me’s wearing a pair. He’s a giant with tiny feet. Size 38 or 39, no bigger. I can’t take my eyes off them. I’ve seen him around town several times but never noticed how small his feet were. I’d never caught the name of the café either, so I ask. They tell me it doesn’t have one. Once upon a time the owner was called ‘Bouin’. But it’s changed hands several times since then. These days, you just go ‘to the café’ or ‘to the tobacconist’s’, depending on what you need.

Staring into space as I wait for my pasta water to boil, I remember Hélène’s phone call. Why on earth did I agree to this ridiculous trip?

‘So, what d’you think? Good idea, isn’t it?’

‘Why don’t we just chill out here for a couple of days instead?’

‘No, thanks. I’ve seen enough of that place; it’s a miserable hole.’

‘But I’ve got work to do. I’m already pushed …’

‘Exactly. What difference is a day or two going to make? If you’re that worried, you could take the typewriter with you and work at the hotel. It’s three days, not a voyage to the ends of the earth!’

‘Three days in England isn’t the same as three days here.’

‘What are you on about?’

‘I know what travelling’s like! You cram so much into every day that it feels like two days in one.’

‘For goodness’ sake, you’re such a homebody!’

‘No, I’m not. I travel all the time, just not from place to place.’

‘Don’t you want to see me?’

‘Of course I do. That’s got nothing to do with it …’

After that, I continued to hear her voice but not the words. A bewitching melody was playing through the little holes in the phone in an unfamiliar and sweet-sounding language. I said yes. Then she hung up.

Now I’m really in the shit. She’s coming to pick me up in two days’ time. Two days is nothing – she may as well have said, ‘I’ll be there in two hours.’ I’m looking at everything around me as if for the last time. I’ll have to speak, and in English to boot! We’ll get lost and have to ask for directions. I can ask for directions in English; I just won’t understand the reply. That’s not going to get me very far! We’ll have to drive on the left, courting death at every crossroads. Hélène’s obsession with avoiding all the places ‘other people’ go will mean she insists on experiencing the dingiest pubs, where I’ll sit wincing while sailors drunk on beer make eyes at her. We’ll have to lug heavy bags from one hotel to another in the pouring rain. I’ll be among people in their natural habitat. Come to think of it, I’m in the same situation as Louis, forced to do things against my will because of the choice a woman has made. Suddenly I’m feeling a lot more warmly towards Louis. Telephone!

‘Christophe, how are things?’

‘Well, to be honest …’

‘Is it Nane? What’s happened?’

‘No, she’s fine – well, there’s no change. It’s not that, or not just that. I dunno. The kids, work, money, time passing, a bit of everything. I’ve been thinking of you by the sea, all that fresh air … If I could find the time, I’d really like to come and visit.’

‘That would be great, only I’m going away the day after tomorrow.’

‘Oh, really? Where?’

‘To England, with Hélène.’

‘Oh, nice! You’ll have to tell me all about it. Right, I’ll let you get on. I’ve got to dash over to Nane’s place, doctor’s coming round. Bon voyage, you jammy git!’

Hardly! True, next to his problems, mine seem on the mild side. His ex-wife Nane is dying in a studio flat somewhere in the sixteenth arrondissement of Paris. Nane was as beautiful as a Sunday, as a day with no purpose, kind, intelligent, perfect. One morning, she walked out of the door without even saying goodbye, leaving Christophe to bring up two kids on his own. He never tried to understand, but carried on loving her as he always had done, like an ox faithfully pulling its plough. Fifteen years went by with no news of her, and then a year ago he bumped into her by chance. She’s ill – very ill. He’s been looking after her ever since, as Nane’s mother ought to have done if only she wasn’t a self-obsessed monster. All that woman has done for her daughter is allow her to rent one of the studios she owns in Paris – at an extortionate price – purely because it would have been a headache to have left her on the streets. If only Louis existed in real life. But he doesn’t, and Nane is so exhausted that the inheritance would be no use to her anyway. Would he even get there in time?

I should have suggested Christophe and the kids come and spend a few days here. I thought about it, but I didn’t do it. Faced with such an outpouring of sadness, I backed away. Hélène would call that selfishness. I disagree. I simply have a great deal of respect for other people’s privacy, in good times and bad.

2

Just before jumping on the bus, Louis saw a well-known actor in the street, although he couldn’t remember his name. He looked smaller than when he was on screen. Days when things like this happened weren’t like other days. On the bus, he sat opposite a little old couple, both sleepy, one with their head on the other’s shoulder. They were like two little old cigarette butts stubbed out on the seat. They gave off the smell of beef stew and waxed parquet. It was as if they were at home at siesta time. Louis was overwhelmed by a wave of emotion, which almost made him feel sick. It was more than tenderness; he was overcome with love for this adorable couple. It was ridiculous, for two stops he struggled to contain his sobs. Then the man gently shook the woman awake; his wedding ring caught the only ray of sunshine that day. A skinny little man took their place. He was carrying an enormous lampshade that he laid on his knees. Louis could only see his eyes and the top of his bald pate. He looked like a thing, an unusual, detachable object. When he left, two young people took his place. Louis hated them immediately. Especially the man. He looked as boring as all the hardware he had just bought at the DIY store, things for cutting, sanding, screwing, measuring, tightening and loosening. For each item he took out of the plastic bag, he read the instructions all the way through, in a low voice like a depressed vicar. The flat-chested blonde who was with him nodded as she listened, dull-eyed and slack-jawed. Their weekends must be a blast!

Under the plane trees, dead leaves glued to the pavement by the rain resembled pamphlets warning of the end of the world. Just before he reached Printemps, a knot in the crowd forced him to slow down. There was a figure, just visible between the legs of the passers-by. It was stretched out on the ground. One trouser leg was rucked up, revealing a pale, almost blue calf and a brown sock rolled down at the ankle of a shoeless foot. The shoe, an old one, was a little further along. A corpse! In newspaper photos of crimes or accidents, the victim had always lost a shoe. Instinctively, Louis looked up at the buildings on the street. The sniper had vanished.

As he pushed open the door of the department store, he was greeted by a gust of warm air and ladies’ perfume which made his head spin. He was instantly horrified at the thought of any physical contact. Feeling bodies brush against his, he had the sensation he was paddling barefoot through slime, sinking into an obscene swarming mass, taking part in a disgusting orgy. He could imagine grubby underwear, soft white flesh, damp body hair, the sickening smell of sweat and saliva.

He felt a bit better when he reached the dome of Brasserie Printemps. The enormous umbrella of light caught the hubbub of conversation and the clinking of cutlery. He quickly spotted Richard, but didn’t show himself. It was absolutely delicious to watch him playing nervously with his knife while looking at his watch or casting a mournful eye over the menu that was almost entirely composed of salads and desserts. He stood out amongst the prim and proper matrons and their granddaughters daubed with banana split.

I won’t go and meet him. Anyway, I can’t give him his money back. I have nothing to give him as security except a brilliant horoscope for the coming month. I’ll leave him stewing there.

A kind of short sigh followed by a thud caused him to turn round. One of the grandmothers at a table near him had just collapsed, her head in her plate of crudités. There was grated carrot in her hair, and a round of cucumber clung to her right cheekbone. By her chair a newspaper with a screaming headline: AGEING SOON TO BE A THING OF THE PAST! No, there certainly wasn’t any sign of the barrel of a rifle with telescopic sight under that shower of fragmented light filtering through the stained-glass panes of the glass roof. The shot could have come from any one of the facets of the giant kaleidoscope.

Louis ran out of the store and walked straight ahead for a long time. Then he sat on a bench, in a large park, the Tuileries, or maybe it was the Luxembourg Gardens. Out-of-work dads recognised each other from afar. There were dozens of them drifting along the avenues, one child clinging to their back like a wart, another dragging its feet in the dust while holding on to their father’s hand. The dads greeted each other with a weary little conspiratorial smile: ‘Welcome to the club.’

There was one beside Louis. He had his eye on a little girl who was sticking her fingers into a drain cover. They were still the fingers of a newborn, soft and pink like shelled prawns. She was burbling incomprehensible sounds full of wet syllables: pleu, bleu, mleu. Her brother, barely any older, was pedalling like a demon round and round the bench on a red tricycle. Other Michelin men, bundled up in their winter garments, threw handfuls of gravel, wooden lorries, spades and rakes at each other. Any object became a projectile in their hands. An hour spent in their company would drive you completely mad. Louis was not unhappy in his state of stupefaction; he was no longer aware of the cold or of the strident cries. Far in the distance gardeners made little piles of leaves, which they then gathered into one large heap. He would like that work, simple and monotonous.

The little girl nearby began to shriek. One of her fingers was caught in the grille. Things like that were always happening to children – life is full of holes and there are so many little fingers. The father got down on all fours, trying to moisten the child’s finger with his spit, murmuring reassurance to her. The child was screaming so much she was turning blue. Women came over to proffer idiotic advice to the poor father, now red with shame.

‘You should have used soap.’

‘You think I come to the park with my pockets full of bars of soap?’

He was envisaging having to pull out the grille and carry it still attached to his daughter’s arm, but the little finger finally came free with a popping sound. The gathering dispersed, disappointed. They had been hoping for the fire brigade. The father stuck a biscuit into his daughter’s dribbling snotty mouth and hastily gathered up the strange assortment of items that children must always have with them – a disgustingly grimy fluffy rabbit, a broken toy car, a retractable transistor aerial, a single roller skate. Had he missed anything? Yes, the little brother, who was pedalling at top speed towards the open gates to the street where huge menacing buses passed, hungry for little boys on red tricycles.

‘Quentin! Come back here immediately!’

We’re all children of children. This unfathomable thought kept Louis going until nightfall, until the time when everyone goes home.

It’s time to go to the beach, but I’m staying put. My throat’s a bit sore and I’ve a slight temperature – excuse enough to slack off for the rest of the day. Goes without saying it’s this England business that’s knocked me for six. With a bit of effort, it seems to me I could be properly ill by the time Hélène arrives. I open the window, unbutton my shirt collar and fill my lungs with the icy air, heavy with moisture off the sea. There – now all I need to do is slip under the duvet fully dressed and spend the whole day sweating, while dulling my brain with German soap operas and game shows. All being well, I should hit between 38 and 39 by the end of the night.

Watching Inspector Derrick’s adventures only serves to give me a stiff neck. I’m better off staring at the wallpaper. I lose myself for a good while in the intricate faded flower pattern on the walls, when suddenly I get the strongest sense that Nane has died, right this very moment – puff! – like a light bulb blowing. All at once, the babbling in my head fades, to be replaced by a surprisingly clear memory of Nane’s last birthday. We were celebrating in the ridiculous studio her mother put her in, on the fourth floor of a modern building in the sixteenth arrondissement. The decor and furnishings are all her mother’s doing. The place is dripping with gold fixtures and walls of sky blue and pink. Every room is fitted with carpet, right up to the loo seats. Nane has never been allowed to change a thing. But what does a bit of fussy decor matter to her when she’s dying anyway? She’s made do with pinning a few postcards above her bed and sticking some flowers in a vase – no more than you’d expect to see in a hospital room. She has set up home in her mother’s place the way a hermit crab moves into another mollusc’s shell. A bed with a TV facing it. She lives off her own death, self-sufficient. Just as Hélène feared, Nane had ‘made herself pretty’. Lipstick and eyeliner only emphasised the sorry state of her poor face. There was Hélène, Christophe and me. We’d just had a glass of champagne. Nane was about to blow out the thirty-nine candles on her cake. It was too much for her; she couldn’t breathe so we had to call an ambulance. Lying on the stretcher, her body under the blanket made no more of a mound than a closed umbrella.

I daren’t call Christophe. I don’t trust this sixth sense of mine. What if it’s just my imagination trying to find an excuse not to go to England? Nane dying would blow the whole idea out of the water. It’s possible to pray for things unconsciously and I wouldn’t put it past myself to do so.

I’m eating leftovers of leftovers and half listening to the news on the radio when I hear a knock at the door. My first instinct is to find a weapon, but then I get a grip: it’s only ten past seven – no one’s killed at this time of night.

‘Evening. I live next door. I’m sorry to—’

‘Yes, I recognise you.’

‘We don’t like to intrude.’

‘What can I do for you?’

‘Well, see, the thing is … our daughter’s going to be on telly this evening. Going for Gold – you know, the game show …’

‘Yes.’

‘Our TV’s just stopped working, so we thought to ourselves, maybe the chap next door might … if we’re not disturbing you … assuming you have a TV, that is?’

‘Yes. I understand. Please, come in.’

‘Oh, that’s kind of you, ever so kind! … Arlette, come on, he says it’s OK.’

Monsieur and Madame Vidal have invaded my solitude. We sit smiling idiotically at one another. They look like a pair of shiny new garden gnomes.

‘The TV’s upstairs. You’ll have to excuse the mess.’

‘Oh, don’t mention it. It’s us who should be apologising, barging in on you while you’re having your supper.’

‘No, no, I’d finished. Come on up – it’s the first room on the left.’

I give the duvet a few whacks and sit my visitors on the edge of the single bed, twenty centimetres from the TV screen; the only way I can watch TV is sprawled on a bed. I feel as if I’m looking after two nicely behaved children.

‘Ooh, it’s starting!’

Since there’s no room to sit next to them, I slide in behind them. Between Monsieur Vidal’s shiny pate and the silver-blue lichen sprouting from his wife’s head, the TV presenter’s unappealing face appears, swiftly followed by those of the contestants wearing nervous or slightly crazed expressions. Among them is Nadine, twenty-seven, a teacher from Rouen, who takes the opportunity to say hello to her students as well as her parents, who have no doubt tuned in to watch her.

‘There she is! That’s our daughter. Gosh, doesn’t she look awful!’

‘Must be the nerves! You know how shy she is …’

Arlette’s hand nestles inside her husband’s. I have the curious feeling I must be at their house. I daren’t move, in case they notice me there. I wonder who Nadine takes after most, her father or mother? Nobody or everybody? In fact she most resembles the TV presenter, bloated as if by a phantom pregnancy, with a look on her face that says, ‘I may be ugly, but I’m highly intelligent.’ We’d hate one another at first sight if we were introduced. She looks a nasty piece of work. How could such a lovely pair of people produce someone with such an inflated ego? And lovely people they are, I’d bet my life on it. This is the first time I’ve seen them up close, but I’ve often spotted them coming back from the market or from a walk, arm in arm, never in a hurry, protected, as though living inside a bubble. I’ve so often imagined and envied the admirably empty, clean and tidy little life they lead together, just the two of them. Every time I have a row with Hélène, and we each go home to our separate houses for the sake of preserving our precious independence, I think of them. Tonight they’re in my home, watching my TV; I could touch them; they belong to me and not to the stuck-up little madam on the TV screen. I want them to adopt me, right now, this instant! I’d be a very good son to them, and what’s more, I live just next door. I could ask them to talk to Hélène, to stop the trip from going ahead …

‘… contains theobromine. Once the seed has been roasted and ground, it is used to make a drink …’

‘Cocoa!’

Father and daughter say the magic word in unison, a split second before the time is up.

‘Cocoa! That’s the right answer! And that makes you today’s CHAMPION!’

For a moment the bedroom flutters with the sound of beating wings as my two angels spring to their feet, clapping their hands. Part of me begrudges that stiff little princess her victory, but it has clearly made the two old things very happy.

‘It’s not just because she’s our daughter – you have to admit she was the best. Ever since she was little she’s always been able to learn whatever she wanted, and she retains it all, doesn’t she, Arlette?’

‘Oh, yes! She’s always been very hard-working as well. It’s not enough to be clever, you have to put the time in too! Besides, they don’t give a teaching degree to just anyone, do they?’

‘No, of course not! Right, I think this calls for a drink. You’ll have a glass of something, won’t you? Ah, go on!’

They won’t stop droning on about their daughter – what about me, huh? We head downstairs. I run three glasses under the tap and open a bottle of Chablis.

‘You’ve got a lovely place here. All these pretty things and pictures; it’s very arty. What do you do for a living?’

‘It’s not my house. I’m renting it from a friend of mine who’s a painter. I write books.’

‘Oh, right …!’

I wait for the ‘Oh, right!’ to come back down to earth, having been blown out into the stratosphere to make way for a toast to Nadine’s starry future.

‘To Nadine! Yum … Nice wine, isn’t it, Arlette?’

‘Very nice! Well, we had you down as being in the film business. We thought we’d seen famous people coming in here. We just happened to notice, you understand! We haven’t been spying on you.’

‘Of course not. It’s true, several of my friends are actors.’

‘Aha! See, Louis? I was right!’

‘Sorry, your name’s Louis?’

‘That’s right. Why?’

‘No reason. It’s a nice name.’

‘Oh, I dunno. Have to be called something, after all. And your name is?’

‘Pierre.’

‘Pierre’s nice too. If we’d had a son, we’d have called him Pierre, wouldn’t we, Arlette?’

‘Yes, Pierre or Bruno. But we had Nadine.’

I offer them another drink. Louis accepts; Arlette covers her glass with her hand. Louis talks about the job he did before he retired, working on the railways. I hear him, but I’m not listening. I’m trying to find my features in his face and, of course, I succeed. The resemblance is actually quite striking. I wonder how Arlette has failed to notice.

‘Anyway, enough about me, we’ve kept you long enough already …’

‘Yes, my husband does like to talk! … Why don’t you come for lunch with us tomorrow? It’s market day. Do you like fish?’

‘The thing is … yes, OK, I’d love to.’

‘We’ll see you tomorrow, then, Pierre! Thanks again!’

Why did I lie about my name? His really is Louis though …

3

Louis’s mother took all her medication for the week in one go on Monday morning so that she could be sure she wouldn’t forget. That was her best day of the week. She laughed at anything and nothing, spent an hour staring at the pattern on her waxed tablecloth, moved her knick-knacks about and invariably ended up embarking on a complicated recipe for which she only possessed a fraction of the ingredients. At eight o’clock, she collapsed in a heap for at least twelve hours.

Louis could smell it from the end of the corridor, something overpowering that caramelised his nostrils and covered his face like a leather mask. The radio and the TV were both blaring. His mother, curled up on the sofa, reminded him of a box of spilled matches. She had the bones of a bird that jutted out at all angles from under her black dress. A tuft of mauve hair indicated her head. Louis turned the volume of the television down, switched off the radio and went into the kitchen, holding his breath, his hand held out towards the cooker knob. Two fossilised pork chops lay on the bottom of a pan coated with burnt chocolate. On the side a cookery book was open at page 104, ‘Cocoa chicken’. Louis opened the fridge and unearthed a slice of ham, a yoghurt and an apple and returned to the sitting room. Before eating, he propped his mother up with cushions, arranged a pillow under her head and laid a rug over her legs. He really liked watching television with her, especially when she was asleep. It was a programme made by Mr Average for Mr Average about Mr Average. Louis didn’t bother to try another channel. He watched the television, not what was on. Exactly like in the street, or anywhere. What was happening in front of his eyes was only a pretext to let his imagination wander. It could be anything or anyone.

Sometimes he would follow someone in the street until he got fed up. The last time had been at Gare de Lyon, a woman with a parcel. She had led him as far as Melun. It must have been about one o’clock and the train was half full. Louis had sat a few seats away from the woman so that he could watch her without her noticing. About fifty, a bony head and torso, but plumper from the waist down. She was reading a magazine, Modern Woman, her elbows resting on the parcel on her lap. The parcel was so well wrapped that it looked fake: brown paper perfectly folded, string taut and knotted into an elegant but solid bow, the name of the recipient written in beautiful block capitals (M— something or other).

The buildings got smaller the further they went from Paris: tower blocks, then four-storey buildings, single houses and finally a cemetery, just before the beetroot fields. Very soon, the same sequence repeated itself but in the opposite direction as they approached Melun.

Melun prison! The package! The woman was going to visit someone in jail. A son? Or a husband more likely. She wasn’t the kind of woman to have children. Melun was for long sentences. How many years had she been making this journey? How many times a week? There was something at once sad and comic in this image of the frumpy woman with the words ‘modern woman’ in her hands. What on earth could the bloke have done to end up in prison? Killed for money? To give it to this woman? At Melun, Louis had let the ‘modern woman’ disappear into the crowd. He understood at once that Melun was a dismal town, flat and useless. He had drunk coffee as he waited for the next train back to Paris.

Louis’s mother let out a little fart, very short, but loud. How much was she going to give him? A thousand francs, two thousand francs? She never refused to give him money, but she gave it sparingly, at little old lady pace, so that he didn’t stray. Even when his father had been alive it had been like that. Benefiting from the invariable paternal siesta, she would take him aside in the dining room. Eight uncomfortable, immovable chairs stood round a table as solid as a catafalque. There was an enormous sideboard in which piles of plates slept peacefully except for the once or twice a year they were taken out. They practically never went into that room, except to polish the furniture, a ritual like going to put flowers on Grandmother’s grave on All Saints’ Day. The rare dinners they gave were always depressing affairs, with his father’s colleagues or family members, a universe of adults as icy as the polished mahogany of the furniture. You had to behave well, which meant you couldn’t do anything you wanted to do. The moment his parents opened the glass doors hung with lace curtains that separated the dining room from the sitting room, they were no longer the same people. They assumed a stiff bearing and spoke in low tones as if they were in a museum. They didn’t like going into the dining room either; they much preferred the kitchen, but that was how it was – grown-ups had obligations, work and dining rooms. It was because of little things like that that Louis had refused to grow up, and at forty, he wasn’t about to change his mind.

‘Louis, are you listening to me?’

‘Yes, Maman.’

‘I already gave you a thousand francs for your car insurance, and that was only two weeks ago. I’m going to give you another thousand but after that I can’t give you any more. We have to have the garage door redone, you know, and that will cost an arm and a leg.’

‘I told you, I’ll pay you back!’

‘Shh! Your father’s next door. I would give it to you if I could, you know that; it’s just … at the moment …’

Louis had not been ashamed of asking them for money. They had money, not much, but more than he had. His mother’s face had been barely visible in the gloom. It was only when she had moved her head that there was a reflection off her glasses. They never put the light on until it was completely dark, either in winter or in summer. Not because they were miserly but out of respect for the memory of an era in which thrift was as much a virtue as a necessity. Louis’s mother had opened the sideboard and removed some notes from an imitation-lizard-skin box. That was where she hid her meagre savings. Everyone had known it, but no one ever mentioned it. Like the dining room, his father’s siesta or the tardy lighting up, it had been part of their little habits as tightly woven together as the twigs of a nest.

‘Put that in your pocket, and don’t tell your father.’

‘Of course I won’t. Thank you, Maman.’

On the other side of the partition, Louis’s father had known perfectly well what was going on between mother and son and it was fine by him. It was part of their game. Louis had crammed the notes hastily into his pocket, which his mother disapproved of; you were supposed to fold notes neatly in two and keep them in your wallet.

‘Right, Maman, I must run now – I’m going to be stuck in traffic. Say goodbye to Papa for me.’

At the end of the road, the entire house was framed in his rear-view mirror. If you had turned it upside down it would have begun snowing.

Something very strange was happening on television. His mother’s date of birth had just appeared on the screen: 7/10/21. Louis turned the volume up.

‘If anyone born on 7 October 1921 is watching, they should telephone us because they have just won this superb caravan!’

A sort of square igloo shiny with chrome filled the screen: WC, shower, folding double bed, electric hob, oven, fridge …

Louis’s eyes widened, like a child in front of a big Christmas toy. He wanted that caravan, he wanted it all for himself. That was where he wanted to live and nowhere else. A brand-new life in a brand-new caravan. It was obvious to him that destiny had made this programme just for him. And that wasn’t all. He wanted everything else as well, everything his mother owned, her meagre savings, the house, her life.

The roll of cling film lying on the table was not there by coincidence. There were no more coincidences, just the last pieces of a puzzle all fitting together perfectly. That was why his mother was turning over, offering her face to the film of plastic Louis was preparing to press over it.

‘Now you are brand new as well, shining and without a wrinkle. This is not going to hurt you any more than the day you gave birth to me. You’re giving me life for a second time.’

There was barely a sound, a soft breeze rustling leaves and fingers opening and closing. The old woman, packaged like a supermarket chicken, had just died without making a fuss.

For a second Louis remembered the lady with the parcel on the train, and her husband in jail in Melun. But that wasn’t going to happen to him; this was just a family affair, just something between him and his mother. It was nothing to do with anyone else. A little sooner, a little later … for his mother it changed nothing and for him it changed everything. A new life was beginning, a proper life, the life of an orphan.

4

To tell the truth, I don’t care that the Vidals are stupid, boring and not especially nice. At the beginning of lunch it bothered me a bit, then I got my head down and focused on the grub and the plonk. I stuffed myself like a goose for foie gras, until they once again seemed beautiful, radiant, unique, the perfect couple. I could tell that my ebullience was causing a few raised eyebrows, but, after all, arty types are always a bit zany. Still, they seemed pleased to see me go after the Calvados coffees.

I love napping on the beach, sheltered from the wind, leaning back against the jetty, my feet buried in the sand, hands in my jacket pockets, face to the sun. Slow explosions of red, green and yellow behind my closed eyelids. When I was little, I used to love pressing my eyes or staring at light bulbs to make fireworks go off inside my head. Arlette used the most marvellous expression when talking about a friend of theirs with a drink problem: ‘His face has been completely defaced by alcohol.’ She comes out with a lot of things like that. It must have been partially aimed at Louis, who was starting to go glassy-eyed after the aperitifs. She stopped him showing me the scar from his operation. ‘Not while we’re eating!’

Three horses gallop by in the distance, down at the water’s edge. I hear their hooves on the hard sand, slightly out of sync. That’s how I’ve been feeling since this morning – just marginally out of step, slightly missing something. It’s not an unpleasant feeling – halfway between spectator and tourist.

This morning, Louis – my Louis – killed his mother. So that’s one thing ticked off. I’ve deflowered him. No sooner had I turned off the typewriter than Hélène rang; the England trip is on hold. (What a shame!) Problems at the newspaper, problems with her daughter, problems as far as the eye can see.

‘Sorry, darling. Poor you. Is there anything I can do to help?’

‘No, love. It’s as if everyone made a pact to be a total pain yesterday. Nat went off on one! I don’t know what’s up with her at the moment.’

‘She’s sixteen.’

‘Yeah, well, it’s no fun. She’s buggered off God knows where. If you hear anything from her, will you—’

‘Of course, if she rings I’ll let you know straight away.’

Poor Hélène, at the mercy of ‘other people’. If only you’d listen to me … We could shut ourselves up here for ever. We’d never go to England, we’d never go further than the beach and we’d see nobody, except the Vidals from time to time. They’re really nice, you know; you don’t have to try to be clever around them. We’d eat, we’d make love, we’d sleep fused together like Siamese twins. War and peace, summer and winter would come and go around us and we wouldn’t notice. It would all be the same to us. What the hell do ‘other people’ have to do with anything? Remember the time we stayed in bed for forty-eight hours? Wasn’t it wonderful?

‘But we can’t spend our whole lives in bed! What would we live off?’

We’d take a leaf out of my Louis’s book, wouldn’t we? Remember after the famous birthday party at Nane’s, after we’d taken Christophe home? In the car, you said, ‘What I find really upsetting is that she’ll never get the chance to enjoy a share of her bitch mother’s money. She could at least have travelled in the last year, done the things she’s always wanted to do …’

‘It’s been years since Nane wanted to do anything. It’s like she’s living the same day over and over again.’

‘Maybe, but it still leaves a bitter taste. When I look at all these old codgers who have more time and money than they know what to do with … My father gets a new car every two years – he only uses it once a month. My mother’s always on the lookout for a new coffee machine – she’s already got seven. Can you imagine? Seven!’

‘You’ll inherit.’

‘Yeah, right! They’re rock solid. Not that I’m wishing them dead, but—’

‘But it’s like our pensions – we’ll be half dead ourselves by the time we get them.’

‘Exactly. What about you? Don’t you think you’d make better use of your mother’s money than she does?’

‘No question.’

‘So it’s only when you no longer want anything that you get to do whatever you like? It’s a joke!’

‘I can never retire anyway – I’ll just have to live off my fame and fortune. As for you, if you’re relying on Nat and her friends to pay for you, things are not looking good. Our best hope is for an epidemic to wipe out the old people this winter.’

‘They’ve all been vaccinated.’

We sat in silence after that, torn between feelings of guilt for having parricidal thoughts and dreams of inheritance. It was a struggle to get out of the car; the night sky looked like a huge empty black hole, or a box of ether-soaked cotton wool for killing kittens. The next day was when we stayed in bed for two days.

I’ve run out of cigarettes. It’s starting to get chilly; the wind has changed. I’ve kept my evening plans to a minimum: a yoghurt and then bed. All of a sudden I feel exhausted, tiredness weighing on me like a great damp coat. Quick pit stop at the nameless café, where I hear it’s going to rain tomorrow. I count my steps as I walk back to the house. I stop at 341; there’s someone crouching outside my door.

‘Nathalie? … What on earth are you doing here?’

‘Just popped over to say hi. Is it a bad time?’

‘Of course not. Come in.’

A gust of icy wind seizes the chance to come inside the house with us. I have a devil of a time trying to shut the door.

‘Louis! Haven’t seen you for ages! You haven’t really changed. A bit fatter maybe.’

‘A little, yes. Hello, Solange, you’re looking good.’

‘If you say it fast enough! But there you go, you can’t make something new from old bones.’

Louis thought otherwise. He smiled at the mother of his first wife, Agnès. A voice from inside the house put an end to this embarrassing exchange.

‘Bring him in, Solange! You can’t just stand there in the doorway!’

‘Yes, of course. Come in, Louis! Oh! Gladioli – you shouldn’t have! Thank you, Louis.’

Nothing had changed, although now the furniture, the walls and Agnès’s parents themselves were coated in a fine film of dust. It had been years since he’d set foot in this house, ten years, maybe more. Raymond, probably reluctantly, turned off the television and poured glasses of Ricard. Solange was twirling about with the gladioli, arranging them in a shaped crystal vase brought back from a trip to Hungary.

‘Cheers, Louis!’

‘To your good health.’

‘Raymond! These drinks are really strong!’

‘So what? That’s exactly what a reunion like this calls for.’

‘Condolences for your mother, Louis – Agnès told us. How old was she?’

‘Sixty-six or sixty-seven, I’m not quite sure.’

‘Oh!’

Louis saw they were subtracting their age from his mother’s and noting with horror the tiny difference. Then …

‘You know, we were really surprised to get your call the other evening, after such a long time.’

‘I’m sure you were. It just occurred to me, after speaking to Agnès. Time passes so quickly.’

‘It does, but nothing much happens in all that time, at least not to us. Just our daily routine. Can I get you another? Come on, just one more.’

That had been last week. From the window of his caravan, Louis watched the barges sliding along the Seine. He had parked his caravan in the Bois de Boulogne campsite. It was very quiet at this time of year. He had been here for two months, since just after his mother’s funeral. He hadn’t worried about her death for a moment. Everyone knew the state of her heart and how she took her medication all in one go. He was feeling good, as he had felt every day of the past two months. He wanted to communicate his happiness to other people. To let them know happiness was possible and it was important to believe in it. So he had opened his address book at ‘A’ and picked up the telephone. The first two ‘A’s had been out, but Agnès answered.