11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

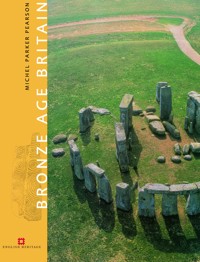

During the Neolithic and Bronze Age - a period covering some 4,000 years from the beginnings of farming by stone-using communities to the end of the era in which bronze was an important material for weapons and tools - the face of Britain changed profoundly, from a forest wilderness to a large patchwork of open ground and managed woodland. The axe was replaced as a key symbol, first by the dagger and finally by the sword. The houses of the living came to supplant the tombs of the dead as the most permanent features in the landscape. In this fascinating book, eminent archeologist Michael Parker Pearson looks at the ways in which we can interpret the challenging and tantalising evidence from this prehistoric era. He also examines the various arguments and current theories of archeologist about these times. Drawing on recent discoveries and research, and illustrated with numerous maps, plans, reconstructions and photographs, this book shows what life was like and how it changed during the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 285

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the discoveries and hard work of archaeologists, both amateur and professional. Geoff Wainwright and Stephen Johnson asked me to write it. John Barrett, Mark Edmonds, Karen Godden, John Moreland, Niall Sharples and Roger Thomas read and commented on various drafts. The following people provided information, help or comments: Richard Avent, John Barnatt, David Breeze, Andy Chapman, John and Bryony Coles, Jane Downes, Andrew Fleming, Claire Foley, Daryl Garton, Jon Humble, Eddie Lyons, Con Manning, Roger Mercer, Jacky Nowakowski, Ken Osborne, Julian Parsons, Francis Pryor, Colin Richards, Joe White and Mike Yates. Pictures supplied with kind permission of the following:

© Alan Braby and Ian Armit: 31.

© Andrew Fleming: 81.

© Andy Lewis: 72.

© Birmingham Archaeology/Gwilym Hughes: 80.

© Canterbury Archaeological Trust: 95.

© www.charles-tait.co.uk: 32, 33, 45, 107, 111.

© Charles-Tanguy Le Roux: 17.

© Colin Richards: 49.

© Corinium Museum, Cirencester: 26, 30.

© Crown Copyright (Historic Scotland): 63.

© Crown: RCAHMW: 76.

© Crown Copyright. NMR: 12, 16, 19, 22, 110.

© Professor David Gilbertson of the School of Geography, University of Plymouth: 9.

© Derrick Riley: 50, 51, 104.

© English Heritage: 10, 14, 20, 25, 27, 34, 35, 40, 42, 44, 48, 54, 61, 68, 82, 83, 86, 112.

© English Heritage Central Archaeology Service: 65, 84.

© English Heritage. NMR: 21, 53, 57, 77.

© English Heritage/Peter Dunn: 56,

© English Heritage/Skyscan Balloon Photography: 23, 58, 59.

© English Heritage/Louise Woodman: 66, 70.

© English Heritage/Jeremy Richards: 67.

© English Heritage/Charlie Waite: 73.

© Essex County Council: 108.

© Fenland Archaeological Trust/Francis Pryor: 100.

© Frank Gardiner/Essex County Council: 101.

©John Barrett/Richard Bradley/Martin Green: 15.

© Ian Hodder: 24.

© Lysbeth Drewett: 89, 90.

© M Parker Pearson: 11, 29, 36, 37, 38, 39, 41, 46, 47, 52, 74, 94, 96, 97, 98, 99, 113.

© Niall Sharples: 62, 103.

© Northamptonshire Archaeology Unit: 28, 69.

© Oxford Archaeological Unit/Alistair Barclay: 78.

© Oxford Archaeological Unit/Ros Smith: 88.

© Paul Halstead: 2.

© Peter Dunn: 3, 4, 5, 55, 75, 79, 85, 93, 105, 106.

© Peter Dunn/English Heritage Central Archaeology Service: 43.

© Robert Bewley: 18.

© Roger Mercer: 13.

© Rosemary Robertson: 91, 92.

© Sheffield Galleries & Museums Trust: 7, 8, 60, 64, 109.

© Somerset Levels Project: 1.

© Stornoway Museum/Mark Elliott: 102.

© Tim Darvill: 6.

© Wessex Archaeology: 71.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

1 THE COMING OF THE FIRST FARMERS

Special feature 1 – Radiocarbon dating

Special feature 2 – The British Isles before farmers

2 TOMBS, TERRITORIES AND ANCESTORS

Special feature 3 – Enclosures

Special feature 4 – Skeletons and burial

3 GEOMETRY IN THE LANDSCAPE

4 THE FIRST METALS

Special feature 5 – Mining and manufacturing metals

Special feature 6 – Causes of change

5 DIVIDING UP THE LAND

Special feature 7 – Pottery making

6 GIFTS TO THE GODS

Special feature 8 – Bronze industries and phases

7 THE LONG VIEW

PLACES TO VISIT

FURTHER READING

INDEX

PREFACE

European prehistory has been classified into three ages since 1836 when a Dane called Christian Jurgensen Thomsen worked out that an age of stone preceded an age of bronze which came before an age of iron. This is known as the three-age system and, with modifications, has remained with us ever since. The Stone Age has been divided into three: an Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic); Middle Stone Age (Mesolithic); and New Stone Age (Neolithic).

Since the three-age system was devised, archaeologists have realized that these divisions on the basis of technological material make little sense when attempting to discuss what actually happened in the past and how ancient communities were organized. The Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age, was a time of gatherers and hunters, people who lived off wild resources. It makes more sense to talk about the New Stone Age as the period of the earliest farmers. Equally, the Bronze Age is a problematic category in social and economic terms. There was considerable continuity across the division between the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age. The Late Bronze Age also shares much in common with the Early Iron Age. Archaeologists still use these terms but only as shorthand to refer to particular spans of time. The terms ‘Neolithic’ and ‘Bronze Age’ are no longer considered to be so helpful for our understanding of what happened. As archaeologists discovered that iron was used in the ‘Bronze Age’ and that metals were in use during the ‘Stone Age’, so they realized that the three-age system had outlived its usefulness.

We are everywhere surrounded by the past. Practically all of the British Isles has been settled for thousands of years. The traces of this occupation are often hard to find. Every successive generation has chosen, to some degree, to preserve or destroy what came before. Others have unwittingly destroyed the remains of the past by cultivating or building on top of hidden remains. Also the agencies of wind, rain and frost, as well as natural decay, have exacted their toll. Sometimes all that is left of a prehistoric settlement is a scatter of worked flints in the soil of a ploughed field. In other, more fortunate circumstances, the foundation trenches, post-holes and pits, and the remains of pottery and bone waste have survived. In the best circumstances, we might be lucky enough to find organic remains such as wood surviving in waterlogged conditions.

The sites on display to the public represent only a fraction of what has survived, with these remains forming only a tiny part of what once existed. Most of our prehistoric remains are unremarkable as places to visit. A flat field may hide a prehistoric enclosure which is only visible from the air at certain times of year. Head for some of the places mentioned in this text and you might find a featureless field, a bypass or a new housing estate. Most prehistoric sites that are worth visiting sit in splendid isolation; islands of prehistory that have survived owing to some lucky accident or other. In cases like the large burial mounds, some were protected by tradition, others were simply too large to flatten without machinery, or were too far from later settlements to be worth robbing for their building stone. For the more adventurous, there are landscapes where prehistoric remains have survived over considerable areas. At the back of this book is a list of some of the more interesting prehistoric sites which are open to the public.

There are books about prehistoric Britain, prehistoric Ireland and prehistoric Europe. This is a book which is about all of these. Ireland and Britain shared the same cultural elements for thousands of years, and the prehistoric past of one cannot be fully appreciated without the other. Equally, these islands were only separated from the rest of Europe in the physical sense. In social terms they were part of Europe and throughout this part of prehistory there were seaborne contacts in both directions. While the direction and intensity of such ventures certainly fluctuated over 4000 years, so many of the changes in the British Isles were linked to events on the European mainland. The changing intensity of these contacts can be used as an index of social change. To write about prehistoric England would make little sense since such a concept did not exist.

Finally, the style of most introductory books on archaeology is that of the authoritative narrative, a mass of observations presented as a solid body of incontrovertible evidence. What interests me are the different perspectives for interpreting the past and the ways in which evidence may be selected to support various theories. Archaeologists are often afraid to show others that there is disagreement and controversy about what happened. Yet this is how archaeology really advances, by proposing different interpretations, critically examining other scholars’ evidence and re-evaluating conventional wisdom. This is a major part of what makes archaeology fun and interesting, so I have tried to bring out some of the controversies that are around at the moment.

INTRODUCTION

This book covers both the Neolithic (the time of the earliest farmers) and the Bronze Age. However, the terms ‘Neolithic’ and ‘Bronze Age’ have been used as little as possible. In their place I have used a different sequence which describes the main social characteristics of successive eras as prehistorians see them today. The first farmers are equated with the Late Mesolithic and Earliest Neolithic (Chapter 1). The age of tombs and ancestors is the Early and Middle Neolithic (Chapter 2). The age of geometry and astronomy is the Later Neolithic (Chapter 3). The age of metalworkers and monuments, overlapping with the previous era, forms Chapter 4 and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age. The age of land divisions is the Middle Bronze Age (Chapter 5). Finally, the age of water cults is equivalent to the Late Bronze Age (Chapter 6).

The span of time covered in this book is some 4000 years, from the beginnings of farming by stone-using communities to the end of the period in which bronze was an important material for weapons and tools. In this time, people developed enormous ceremonial monuments, many to house the remains of the dead, later abandoning them to build similar monumental edifices of a different form. These were the field systems, defended hillforts and more permanent dwellings. People did not simply substitute a landscape of ritual monuments with the more pragmatic monuments of fields and farms. Rather, their ritual and spirituality were incorporated, by the end of the Bronze Age, into the dwellings in which they lived.

The face of the British Isles during this time also changed profoundly, from a forest wilderness to a large patchwork of open ground and managed woodland. Vast areas were deforested, never again to grow trees. There were also slight changes in the climate. The earliest farmers lived in a climate which was one or two degrees warmer than it is today. Small temperature differences can have considerable effects on the ability to grow crops in the uplands. Around 3500 years ago temperatures were equivalent to today, but they fell even lower by the end of the Bronze Age.

Archaeologists have continually asked themselves what kind of society existed then. We know a lot about the practices of everyday life but the evidence for political life is ambiguous. There were certainly times of considerable reorganization but there were also very long periods of stability. The early farming communities seem to have been more egalitarian than the warrior clans of the Later Bronze Age. Throughout this period, ultimate authority was doubtless vested in the heavens and in the ancestors, but towards the end there were marked differences amongst the living. By the end of the Bronze Age most people inhabited ordinary roundhouses, but some lived in huge defensive strongholds and controlled access to resources such as bronze. These may have been chiefs, with large retinues of warriors at their command. Some archaeologists have interpreted changes from the Early Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age as the evolution of an increasingly hierarchical and class-based society. But no doubt different political transformations occurred in various regions. There may well have been hereditary chieftains amongst the early farmers, but there were probably also communities headed by councils of elders. It will always be difficult for us to distinguish between these models.

The time of the early farmers (conventionally the Earlier Neolithic) may be considered as an age of ancestors and tombs. In their monumental tombs were mingled the remains of previous generations, with all their bones mixed together. Fire and axes were used to clear areas of forest for cultivation. The axe was the supreme tool of the age and it was an important symbol for these farmers. The manufacture and use of the axe, and its eventual disposal, seem to have been charged with magic and symbolism beyond its everyday practical purposes.

From the orientations of some of their tombs and monuments, we can see that these farmers had a basic appreciation of the cycles of sun and moon. By the Middle Neolithic (5500 to 5000 years ago) they were building monuments to the dead which incorporated a growing concern with the movements of the celestial spheres. This age of astronomy saw the construction of many enormous monuments within ‘sacred’ landscapes. Perhaps these communities were ruled by dynastic chieftains, who organized the large work gangs required for these tasks.

The early use of copper and bronze began in these contexts. There was the adoption of a more individualized type of pottery: beakers, probably for drinking mead, were placed in individual graves. This rise of individualism in funerary practices has been hailed as evidence for chiefdoms, but it may in fact signal their demise. Burial, or destruction, of exotic personal possessions after death may have formed part of a way of life that shunned hereditary inequality.

Large tracts of upland were divided up at least 4000 years ago. The stone circles and other ceremonial monuments of the Earlier Bronze Age seem to have lost much of their importance. The latest ones were not only smaller but were concentrated in the agriculturally more marginal regions of the British Isles. Settlements became solid and semi-permanent fixtures in the landscape for the first time. In contrast, the physical remains of the dead, formerly so dominant in people’s lives, went backstage. An architecture of the dead was replaced by an architecture for the living. Ancestors may still have been important but their power resided in the houses and settlements of the living.

Towards the end of the Bronze Age, the sword had replaced the axe. Warfare seems similarly to have become highly significant. It was to the land and particularly to water that sacrifices and offerings were made. Large quantities of bronze weapons and tools were thrown into rivers and other watery locations. Many of the uplands were abandoned and settlements congregated in the river valleys. Concern with community defence in hillforts accompanied the profusion of weapons of war.

We still know little about this age before written records. Every year brings new discoveries, some of which dramatically alter our understanding of what happened. Our interpretations also change as a result of re-examining old evidence. The account that follows is based on advances in research made largely in the last three decades. It will soon be out of date as more evidence comes to light and as newer interpretations are formulated. The past is never fixed; it is constantly being rewritten. And we must also remind ourselves that, back in the Bronze Age, people were also ‘rewriting’ their past through the monuments and artefacts of their daily lives.

1 THE COMING OF THE FIRST FARMERS

In the spring of 1970 Raymond Sweet, an employee of the Eclipse Peat Works, discovered a plank of wood buried deep in the peat of the Somerset Levels. His discovery was to lead to one of the most significant advances in archaeology in recent years – a wooden trackway built at the time of Britain’s earliest farmers. The peat works sent the planks to John Coles, a Cambridge archaeologist who had been studying the Levels for some years. That summer he came over to Somerset and carried out an archaeological excavation on the site where the timbers had been found.

We now know that the timbers formed part of a trackway that was built across the low-lying, marshy Levels, during the winter months exactly 5777 years before they were rediscovered by Mr Sweet (1, see here). This trackway linked the Polden Hills with Westhay Meare, at that time an island surrounded by marshes. Today the Levels are no longer marshes but drained meadows. The precise dating of the trackway has been achieved by dendrochronology. The age of a tree can be gauged by the number and pattern of its growth rings. The thickness of each ring depends on the particular climatic conditions of that year, so that, over a span of fifty or more years, the variation in thickness of the rings produces a distinctive ‘signature’ for that period of time. From finds of oaks of different ages preserved in bogs, archaeologists have been able to fit together a full sequence of tree rings which goes back well over 7,000 years. It has been possible to fit the distinctive signature of the ring sequence from the Sweet Track’s timbers with the master sequence, to work out just when the trees were felled. The oak trees incorporated into the trackway were cut down in the winter of 3807 to 3806 BC. They were probably split into timber and laid as track soon after.

Who were the builders and why did they construct trackways such as this? We are not sure of the answers to these questions but there are a number of clues, patiently gathered by archaeologists over many years under the direction of John and Bryony Coles. We cannot be absolutely certain that the builders were farmers but they used farming equipment. The wood was cut with stone axes. Someone even placed a special axe made of green jadeite by the side of the Sweet Track. A pot filled with hazelnuts was also broken there. Gatherer-hunters in Britain did not know how to make pottery and the appearance of pottery is associated with the appearance of farming. There was also a small collection of struck flint flakes strewn along the line of the track. Their broad and long blades are characteristic of the farmers’ flint technology, very different from the small and delicate flints (called ‘microliths’) of the gatherer-hunters.

1 The Sweet Track under excavation.

The track may have linked communities living on the Polden Hills with people living on the island. The trackway also provided a corridor along which people hunted the wildlife of the marsh. The Sweet Track was not an easy route to traverse. The walker had to negotiate a slippery plank less than 25cm (10in) wide, pegged and jammed into place between diagonal timbers. Construction of this track was not a major task, even though it ran for over a kilometre. It would have taken just a dozen people only a single day to lay it. However, the preparation and transport of the timbers would have taken much longer. Thousands of wooden pegs, planks and rails had to be manufactured, involving the selection and felling of trees, the splitting of logs and the working of timber. This required the work of at least two small communities (working in different areas of woodland at either end of the trackway) during the preceding year. The timbers then had to be assembled along the route in the weeks before the track was laid. The trackway was repaired over the next ten years but fell into disuse after that.

THE ORIGINS OF FARMING

The Sweet Track was built around the time that farming communities were established in Britain. We can distinguish the remains of these farmers from those of gatherer-hunters in several ways. The first farmers used polished stone axes, pottery and a new flint-knapping technology; they raised animals and grew crops which we recognize as domesticated. These domesticates can be identified from the food remains: for instance, the bones of cattle, sheep and pigs and the charred remains of wheat and barley seeds. Cereal pollen can also be identified in peat bogs and other accumulated sediments. However, there is a controversy over just how and when farming arrived in these islands.

Farming originated in the Near East around 10,000 years ago. Local wild species of animals and grasses in that region had been carefully bred for thousands of years to improve their manageability and yield. Wild cattle, sheep, goats and pigs were probably herded and ranched, while stands of cereal were carefully tended. The domesticated animals were smaller than their wild counterparts while the grass seeds were larger. The sheep were like the modern Soay breed (2), while pigs were smaller versions of wild boar. It seems that a ‘package’ of all these species of animals and cereals was combined to create a farming lifestyle. Archaeologists used to say that farming had been ‘invented’ simply because it was a naturally better way to live, because it represented progress and development. Recent evidence has led them to question this assumption. To begin with, farming requires considerably greater inputs of labour than a gathering-hunting lifestyle. People have to work harder to clear trees and vegetation, break the ground, sow crops, control stock, prevent stock eating the crops, and harvest the crops. Equally, mobility is severely curtailed. Whereas bands of gatherer-hunters can roam over a large area collecting food in different places in different seasons, farmers have to stay in one place to look after the stands of wheat and barley. The animals may be moved to new pastures during the year but, by and large, the only long-distance movement is through migration caused by population expansion. Labour power, far more than land availability, seems to have been at a premium for early farming communities. Women’s reproductive capabilities were a key resource; the more children, the more land that could be cultivated. Farming was probably linked to a population explosion. As people became sedentary, so it was possible to bear and wean more children.

2 Soay sheep, very similar to the sheep of the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

It has been suggested that the adoption of this laborious and sedentary way of life was due to necessity rather than any perception of longer-term benefits, such as the ability to store food in bad years. From the remains of earlier communities in the Near East, from the period just before the development of farming, archaeologists have inferred that they hunted an increasing diversity of animals, including those which were smaller and harder to catch. From the surviving animal bones thrown away as rubbish, archaeologists considered that people’s diet shifted from the large, slow-moving mammals to smaller game such as birds and fish. It has been suggested that this was because they had hunted the larger game almost to extinction and were forced to invent new ways of catching and trapping their food. However, recent research has indicated that this ‘broad spectrum’ revolution in methods of obtaining food may in fact never have happened.

1 RADIOCARBON DATING

Archaeologists dealing with the prehistoric period have to depend on radiocarbon dating to work out the age of sites and artefacts. The technique was developed after World War II and enables a date to be determined as an expression of probability within a specified range of time. Prehistoric remains can be dated only approximately, to periods within 200 years and sometimes less. Previously, archaeologists had dated prehistoric remains in Britain and northern Europe by extending chronologies based on artefact styles across Europe from Egypt and the western Mediterranean, where early written records gave some basis for dating artefacts. Radiocarbon dating revolutionized this framework. We now know that the earliest farmers were here at least 6000 years ago, over a thousand years earlier than had once been thought.

The radiocarbon method works by measuring the decayed half-life of a carbon isotope, C14 which is present in the atmosphere and is absorbed by all living matter. The C14 starts to decline as soon as the living matter dies (for example, when a tree is chopped down). It was initially assumed that the rate of C14 in the atmosphere was steady, but studies of annual growth rings from the oldest tree in the world, the bristlecone pine, have discovered that there have been variable amounts of C14 in the atmosphere. The calculated half-life of a sample has to be calibrated against this variation. The sample itself is dated by estimating the probability of its falling within a certain period of time, normally within three or four hundred years. Within Europe, prehistoric dates are conventionally referred to as Before Christ (or BC). In other parts of the world there is a growing trend to refer to dates as Before Present (or BP). Present is taken as AD 1950, when radiocarbon dating had become established. The dates used in this book will use BC conventions. Radiocarbon dating can be applied to bones, antler and horn, timbers and vegetable matter (whether burnt or waterlogged), peat and organic matter in soils. The advantage of its applicability to common types of archaeological evidence is balanced by its relatively coarse estimations, reliable to within a few hundred years; this may be fine for those who deal in thousands of years. In contrast, dendrochronology can only be applied to well-preserved, waterlogged timbers but it does give us very precise dates indeed. This is how we know, for example, that the timbers of the Sweet Track were felled over the winter of 3807 and 3806 BC.

It is always difficult working out what a thousand years – or even a hundred – mean in human terms. Perhaps the most effective way is to consider time in human generations. The conventional length of a generation is taken as 27 years so there would be just under four in a hundred years. The Sweet Track was built by people some 215 generations before us. Those of us who have traced family trees will grasp just what considerable depths of time are involved in even 20 generations.

3 Time chart from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age.

Theories such as this portray the earliest farmers, and their predecessors, as helpless victims of their environment, forced to alter their lifestyles as a result of changed natural circumstances partly of their own making. A recent theory has challenged this view and proposes that the whole process of domestication was a long-term social development in the way that people perceived themselves and their food resources as ‘domesticated’.

This change was not caused by necessity but by new circumstances of living in larger groups. As food resources became more and more reliable in the Near East, so people stayed increasingly in one place. Living in large, sedentary communities brought new challenges and pressures. People had to live together as never before and find ways of co-operating as well as competing. Status and position became important concerns and were dependent on holding feasts and controlling the supply of food. People ‘domesticated’ themselves as well as their food supplies. New attitudes to what was meant by the terms culture’ and ‘nature’, wild’ and ‘tame’ may well have been embodied in the ways that their houses were built and their dead buried.

Once farming had become firmly established throughout the Near East (in what is now Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and Israel), it was adopted by adjacent communities who acquired the domesticates. The farming package had reached the central European plains of what are now Slovakia and Hungary by the sixth millennium BC. It took only a few centuries for farming families to expand and spread westwards across the light soils to reach what is now the area covered by the Netherlands and northern France.

HOW AND WHEN DID THE FARMING PACKAGE ARRIVE?

There is no doubt that domesticated animals and plants had to be carried by boat from the continent of Europe to the British Isles. There are a number of options. Groups of pioneers could have set off from the continent in one-off small-scale invasions. Or people might have arrived after a long-term and eclectic mixture of contacts down the continental coast from Denmark to France. Or gatherer-hunters might have travelled by boat to the continent and brought back the animals and plants as the result of slowly developing exchange contacts. There is no answer to this puzzle, which is all the more intriguing since the earliest evidence for farming in the British Isles comes from Ireland and probably the Isle of Man, and not from southern Britain.

The gatherer-hunters of the British Isles lived in a relatively sophisticated society. Glimpses of their way of life may be caught very occasionally where there is waterlogged preservation of the complete range of their material remains. For the clearest picture of their lifestyle, we must look at the splendidly preserved sites across the North Sea. Excavations at Tybrind Vig in Denmark have uncovered the wooden and organic remains that have often been lacking on sites in this country. In many ways this was the ‘Wood Age’. They were skilled woodworkers, producing logboats and ornate, decorated paddles. They had nets and traps for fish, and beautifully made harpoons and fish spears.

Whilst gatherer-hunters lived in primitive and temporary ‘benders’ (huts built of branches and stakes), they were by no means isolated groups. We can find the material evidence of contact between different regions by examining their stone tools. In northern Ireland and southern England, some of their stone axes can be shown to have originated from particular rock outcrops. It appears that the axes were moved some distance from where they were made to where they were eventually discarded. A distinctive type of chert (a flinty rock used to make stone tools) has been found across most of southern Britain but it outcrops only at Portland Bill. These tools travelled long distances, presumably because they were exchanged between different communities. The stone tool kits of microlithic flints (small blades and points) also reflected regional styles, which may have corresponded to social territories. People were capable of sailing far from land, as the evidence of deepwater fish in their diet shows. It is just possible that they changed to a farming lifestyle by crossing the Channel and bringing back domestic crops and animals. When farmers reached central and northern Europe they developed a distinctive way of life. They lived in large wooden longhouses (5m (16ft) wide and up to 30m (98ft) long) which were plastered on the outside with mud dug from ditches on either side of the house. They used pottery vessels (4), stone axes and chipped stone tools. They exploited the lightly wooded loess plateaus of northern Europe (loess is a light, free-draining and fertile soil, accumulated as windblown silt during the last glaciation). These were areas uninhabited by indigenous gatherer-hunters, who exploited the species-rich environments of lakesides, rivers and coasts.

4 Early Neolithic pots found in the Somerset Levels.

5 A view over an early farming landscape on the loess lands of Europe, showing the longhouses built by the settlers.

When the farmers of central Europe reached the western limits of the loess plains around 5500 BC, they seem to have gone no further west for some centuries (5). In the Netherlands, Belgium and western France farming did not travel the next 100km (62 miles) for another 500 to 1,000 years. As well as reaching the margins of the loess, farmers also came face to face with the gatherer-hunters of the coastal margins of north-west Europe. What happened between these two groups we may never know. Sites in Holland have shown the use of imported cereals and pottery by gathering communities by 5000 BC, but the full range of domesticates did not appear until 500 years later. This time lag is also apparent in Denmark where the gathering-hunting lifestyle continued unchanged by the presence of farmers to the south until 4500 BC. The communities of the coastal fringe were gradually adopting elements of the lifestyle of the new colonists from the east. To add to the pressures of contact, the sea level continued to rise. Large areas of coastal plain, prime environments for wild food, became submerged during this time. People may have been forced partly by climatic circumstances to adjust their way of life or take up a new one.

Most archaeologists consider that the interaction and contact between gatherer-hunters and farmers must have been complex and drawn out over hundreds of years. The farming lifestyle which eventually took root in the British Isles shared elements with all the contact areas along the continental fringe of Denmark, Belgium, Holland and France.

THE ELM DECLINE AND BEFORE

Until quite recently, archaeologists and palaeobotanists were fairly certain that the beginnings of farming in the British Isles occurred around 6300 to 5500 years ago (4300 to 3500 BC). Within this date range (between 4300 and 3250 BC