21,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

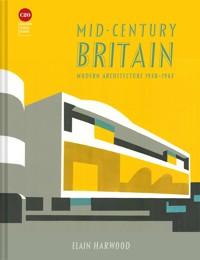

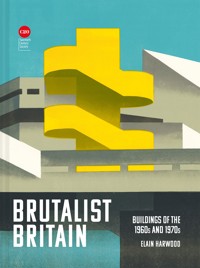

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Introducing Britain's finest examples of brutalist architecture. Brutalist architecture is more popular now than it has ever been. Imposing and dramatic, with monolithic concrete exteriors, it forms an enduring part of our post-war urban landscape. This beautifully photographed book is an authoritative survey of the finest British examples from the very late 1950s to the 1970s, from leading architectural writer Elain Harwood, following on from her acclaimed books on art deco and mid-century architecture. It features iconic public buildings like London's National Theatre, imposing housing such as the Trellick Tower in West London and Park Hill in Sheffield, great educational institutions including the University of Sussex, and places of worship such as Liverpool's glorious Metropolitan Cathedral, along with some lesser-known buildings such as Arlington House on Margate's sea front. Headed up with an introduction that places British brutalism within the context of global events and contemporary world architecture, the huge range of buildings is arranged into Private Houses and Flats, Public Housing, Educational Buildings, Public Buildings, Shops, Markets and Town Centres, Culture and Sport, Places of Worship, Offices and Industry and Transport, and there is a chapter on the atmospheric brutalist sculptures and murals that dot our cities. If you're part of the increasingly large ranks of brutalism fans, or interested in late 20th-century architecture and society in general, Brutalist Britain is the book for you.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

BRUTALIST BRITAIN

PRIVATE HOUSES AND FLATS

PUBLIC HOUSING

EDUCATION

PUBLIC BUILDINGS

SHOPS, MARKETS AND TOWN CENTRES

WORKS OF ART

CULTURE AND SPORT

PLACES OF WORSHIP

OFFICES AND INDUSTRY

TRANSPORT

INDEX

PICTURE CREDITS

BRUTALIST BRITAIN

This book describes some of the most forward-looking buildings ever seen in Britain, constructed on a scale and with an ambition unlikely to be repeated. We can wonder how they happened as we might admire an elephant or black rhinoceros; these buildings have a similar vulnerability. They are big, grizzled and – though 60 years is recent for a building – share a similar air of running out of time. Perhaps no other architecture is so distinctive and defines so short a period. The 1960s saw glitz and glamour, new products, young stardom and space-age science – real and fictional – like no other. Australians describe the fascination that these years hold, particularly for those too young to have been there, as ‘the Austin Powers effect’. That so much sparkle was complemented by raw concrete may seem contradictory but, unlike expensive steel and inflexible brickwork, concrete could be pushed into almost any shape and size thanks to reinforcement and formwork.

Brutalism was the name widely if warily used to describe all that was biggest and boldest, even overweening, in modern architecture. It became a term of bemusement or even disgust, however, until the 2010s, when a new generation around the world rediscovered the buildings’ power, sensuality and imagination, just at the point of their extinction. Few anywhere have statutory protection, but even the crudest have details that delight.

The opportunity to build on such an extensive scale came with the Second World War. The war saw 200,000 houses across Britain destroyed and 250,000 made uninhabitable, but equally important stimulants to renewal were backlogs of building from the 1930s, slum clearance, population growth and migration. As early as January 1941 the popular magazine Picture Post devoted an issue to the rebuilding of Britain after the war. The editor Tom Hopkinson argued that ‘Our plan for a new Britain is not something outside the war, or something after the war. It is an essential part of our war aims.’1 His demands for decent food, education and healthcare saw expression in a government report on national insurance by William Beveridge published just as the war turned in Britain’s favour late in 1942. Beveridge challenged five evils: want, idleness, ignorance, disease and squalor. Legislation for new schools and housing followed, and the Labour Government elected in 1945 introduced the National Health Service, nationalised and invested in heavy industry and transport, and initiated a programme of new towns.

Yet Britain was nearly bankrupted by the war, materials were in short supply and for the next decade the focus was on restoring industry and feeding the pent-up demand for goods. The greatest concern was that the mass unemployment of the inter-war years, hard-hitting in the North, Scotland and Wales, should not return. Economic recovery was delayed by the Suez Crisis of 1956; when it came, it unleashed the biggest construction programme Britain has ever seen, from schools and houses and new buildings for entertainment and sport to the remodelling of major city centres with offices, shops and car parks, and the building of whole new towns. The Conservative and Labour governments of the 1960s and early 1970s competed to have the largest building programmes. The Labour leader Harold Wilson argued for building in the ‘white heat’ of a scientific revolution based on new technology and cheap power, when speaking in Scarborough a year ahead of winning the general election of October 1964.

THE NEW BRUTALISM

While the French architect Le Corbusier was the movement’s poster-boy, the term brutalism was coined in the United Kingdom. In its origins, it did not mean big or brash – though when Reyner Banham was asked in 1963 to write his epic account, The New Brutalism, his students were beginning to think that way. He describes a movement that began in the early 1950s with the Independent Group (a splinter group of young artists connected with the Institute of Contemporary Arts) at Saturday gatherings at the French pub in Dean Street and Sunday coffee mornings in his own home. The origins of the name remain mysterious, with Banham repeating gossip from the photographer Eric de Maré that ‘new brutalism’ had been used by Hans Asplund in Sweden in 1950 to describe hard-nosed buildings that countered the decorative new humanism that had become its national style – what we now term ‘mid-century modern’.2

Smithdon School, Hunstanton, Norfolk, 1950–53 by Alison and Peter Smithson.

The architects Alison and Peter Smithson came to prominence when in 1950, aged 21 and 26 respectively, they won a competition for a secondary school in Hunstanton, Norfolk. Opened in 1953, though not fully completed until the following year, the design was inspired by Mies van der Rohe and a Royal Academy course in neo-classicism; Rudolf Wittkower’s Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, published in 1948, not only reinvigorated the study of proportions but made them relevant to the era of the welfare state. Hunstanton is a steel structure and, though its finishes and services within and without are exposed, it slightly predates their thoughts on brutalism; nevertheless, its acclaim gave them a public platform. Guy Oddie, Peter’s student friend, claimed that ‘new brutalism’ was coined at a dinner party given in about 1952 by Alison and their landlord Theo Crosby, as a pun on Peter’s student nickname of Brutus – a comment on his profile and hated by Alison.3 Reporting ‘errors of fact’ by Banham, the Smithsons explained that ‘“New Brutalism” was a spontaneous invention by A. M. S. [Alison] as a word-play counter-ploy to the Architectural Review’s “New Empiricism” ... The “brutal” part was taken from an English newspaper cutting which gave a translation from a French paper of a Marseilles official’s attack on the Unité in construction, which described the building as “brutal”.’4 The historian Alan Powers unearthed the article on Le Corbusier’s newly completed block of flats in Marseilles, the Unité d’habitation, which gave credence to this story. ‘Alison coined it on the john,’ Peter grunted when interviewed in the 1990s.

It is thus possible to link brutalism to the French term béton brut, concrete that is not smoothed down after casting but is left showing the patterns, seams and fixings of its formwork. It shares the rawness sought by Jean Dubuffet and his Art Brut movement in the 1940s. The Smithsons’ own interest in outsider art bore fruit in the exhibition Parallel of Life and Art at the ICA in 1953, where they assisted their friends and collaborators Nigel Henderson and Eduardo Paolozzi in selecting illustrations of beauty in unorthodox places.

Unité d’habitation, Marseilles, 1947–52 by Le Corbusier.

Banham was right to think of the new brutalism’s greater formalism as a counter-movement to the prevalent enthusiasm for gentle Scandinavian design. This expressed the soft Swedish social democracy that was a model for the British welfare programme of the late 1940s. The two camps polarised in the architect’s department of the London County Council (LCC), best seen in two prestigious housing estates situated barely a mile apart. Alton East expressed Scandinavian ideals and its architects’ social commitment in contrasting brick and colourful tiles, while Alton West used storey-high concrete panels and a greater openness of scale. The two groups were later termed ‘herbivores’ and ‘carnivores’ by Hugh Casson and others, inspired by Michael Frayn’s article recalling the 1951 Festival of Britain.5

The Smithsons, whose later career in writing and teaching honed their skills in self-publicity, were the only architects to embrace the term ‘new brutalism’.6 However, the work of Bill Howell, Stirling and Gowan, Colin St John Wilson and their partners followed a similar programme. In December 1953 the Smithsons illustrated a house whose construction in concrete, brick and wood would have been left exposed inside and out, commenting that ‘had this been built, it would have been the first example of the New Brutalism’. A single-page manifesto entitled ‘The New Brutalism’, produced with Theo Crosby for Architectural Design in January 1955, considered the honest construction of brick and timber buildings as well as concrete to be brutalist, with references to Japanese temple architecture, ‘peasant dwelling forms’ and Frank Lloyd Wright as well as the Unité.7 Banham followed with an article in the Architectural Review later in the year. John Summerson, a critic from an older generation, thought Banham had ‘tickled up’ the movement, but admitted that ‘once every thirty years, there is a big sneeze in architecture. A new movement is due, and Mr Banham perfectly well knows it.’8

The first clear example of the new brutalism was a modest house in Watford by the Smithsons for an engineer and his wife, Derek and Jean Sugden. It appears externally conventional save for its large sloping roof and ‘L’-shaped windows, though internally the brickwork and concrete beams are exposed and its joinery left unpainted. This was in tune with the Smithsons’ growing belief in an architecture of ‘ordinariness’, introduced in an essay in 1952–53 and later defined as creating neutral spaces for clients to personalise, or what they called ‘inhabitation’. Their London offices for The Economist magazine built in 1962–64 were a neat reinterpretation of classical proportions clad in stone. In their later schemes – including housing at Robin Hood Gardens – it was the planning and above all the routes through a building or complex that became critical.

FOREIGN INFLUENCES

British architects quickly made the pilgrimage to Marseilles to see Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation. It was a special commission, built with government support to honour the Marseillais’ bitter fight against Hitler, and was the climax of Le Corbusier’s long career planning decent flats at extremely high densities. As The Times reported, ‘The building has from the first provoked violent controversy, and a campaign was recently launched against the architect for erecting a building which “presents drawbacks of a moral character, contrary to French style and aesthetic standards”.’ Opposition to brutalism began early. The Unité is a giant slab some 17 storeys high and three times as long, though counting the storeys is difficult since many spaces are of double height, including the open ground floor where the building’s weight is borne on two lines of pilotis or piers resembling the flippers of a troupe of giant seals. The block originally stood in open land and even today has few amenities nearby, so two of its upper floors are lined with shops, a café and professional chambers (for doctors, solicitors etc.), while the rooftop featured a crèche and running track. The in-situ concrete bore the marks of its timber shuttering and precast parts were rubbed down to expose a rough aggregate. The juxtaposition of different proportional systems, mixed uses, complex sections, heavy materials and pilotis became the basic language for brutalism in its heroic form of a decade later.

Architects did not have to visit Le Corbusier’s buildings to experience their thrall. Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, the architect first came to prominence as a journalist, adopting a pseudonym based on an old family name and playing on its imagery of a ‘corbeau’ or raven. He then became the first modern architect to publish all his buildings and projects. Eight volumes of the Oeuvre Complète appeared between 1929 and 1970, with summaries in English and German, in which he addressed the problems of high-density urban living, traffic planning and modern housing ahead of anyone else. Their publication was a major event. Alison Smithson admitted that ‘When you open a new volume of the Oeuvre Complète you find that he has had all your best ideas already, has done what you were about to do next.’9 Before the war he had produced a series of elegant, white-walled concrete houses, then used the same wholly modern idiom while reconnecting with traditional stonework. But after the war his work embraced rugged textures and complex proportions. As well as five unités, including one in Berlin, Le Corbusier designed two seminal religious buildings – the chapel of Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp (1954) and the monastery of La Tourette at Éveux near Lyons (1960), and a capitol complex for the new city of Chandigarh in India (1954–64).

The generation of architects born in the 1920s and early 1930s took information from an increasing number of foreign sources. With more books and magazines available, and greater opportunities to travel – particularly on student scholarships – it became easier for young architects to look still further afield for inspiration. James Morris and Robert Steedman secured Carnegie scholarships to explore Europe on a motorbike in 1953, when the Unité at Marseilles was one of the few new buildings to have been completed. Then, in 1956, they won scholarships to study in Philadelphia, where their lecturers included Ian McHarg, Philip Johnson and Louis Kahn.

Assembly Building with Secretariat to rear, Chandigarh, 1954–64 by Le Corbusier.

When Peter Womersley first began working in Scotland in the mid-1950s, his private houses had closely followed Miesian lines. But then, as he explained in 1969, ‘How long can you develop an intellectual ideal, particularly if it has to get more “less” all the time? Should not every building be a fresh re-building of experience gained on other buildings? Should there not be development and enrichment at all times, if atrophy is not to set in?’10 While his contemporary Robert Venturi wrote that ‘less is a bore’ and developed post-modernism, Womersley found what he called ‘heart’ from brutalism. The buildings he listed as exemplars were admired by many of his contemporaries. They began with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and Le Corbusier’s Pavillon Suisse and Ronchamp chapel, then moved on to buildings by the next generation, including Kenzo Tange’s Olympic buildings and Kunio Maekawa’s concert halls in Tokyo, John Andrews’s Scarborough College near Toronto, the Marchiondi Institute by Vittoriano Viganò at Milan, and Skidmore Owings & Merrill’s Mauna Kea Hotel on Hawaii.

In 1955, James Stirling was one of the first British architects to visit Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaoul, a pair of new houses in Neuilly-sur-Seine on the edge of Paris. Their board-marked concrete frames and arched vaults, along with a crude infill of rough brickwork, were inspired by the vernacular of northern India seen by Le Corbusier at Chandigarh. In turn the idiom can be found in housing and university buildings around Britain as perhaps nowhere else. For Banham the greater emotionalism of Stirling’s work with James Gowan made it more exciting than the Smithsons’ restrained Economist group (1962–64) and heralded the dynamic 1960s after years of austerity. ‘I suppose they’ll call it brutalism,’ Stirling grumbled in 1961, anticipating reaction to his and Gowan’s re-interpretation of a Victorian working-class terrace at Avenham, Preston (demolished).11 Their engineering faculty building for the University of Leicester was Britain’s most distinctive post-war building, the red brickwork and north rooflights of local factories combined with the exaggerated angles of Russian constructivism. Stirling (without Gowan) went on to design still more controversial buildings at Cambridge and Oxford, which together have become known as the Red Trilogy.

Engineering Building, University of Leicester, 1959–63 by Stirling and Gowan.

Another version of the Maisons Jaoul, on a far grander scale, was Churchill College, Cambridge, built to train the budding scientists of the space age. The competition held in 1959 marked a coming-of-age for modernism; after a decade where it had become the natural vehicle for lightweight schools and housing, the competition brief asked for a design of our times that would last 500 years and be a memorial to Britain’s wartime hero. Stirling and Gowan’s design was shortlisted, but the winners were Richard Sheppard, Robson & Partners, who devised a concrete frame infilled with gnarled yellow brick and made a feature of giant arched vaults over Cambridge’s largest dining hall.

RAW CONCRETE

The Second World War had seen building materials in short supply, and concrete was used for huts, hangars and housing. These shortages continued into the 1950s, in part because brickmaking could not keep up with demand, in part because of the pound’s poor exchange rate against the dollar, which limited the amount of softwood and steel that could be imported from Scandinavia. A wartime licensing system remained in force until November 1954 to direct materials into essential housing, schools and industry. Brick shortages continued through the 1950s, and a crisis when the economy boomed in 1960–62 was exacerbated in early 1963 by three months of snow and frost across Britain. The LCC resorted to erecting prefabricated bungalows, not seen since the mid-1940s, and authorities everywhere explored new construction methods that were quick, economical and required little skilled manpower (also in desperately short supply).

Concrete again provided the solution. The Romans had exploited the hydraulic lime and pozzolanic ash binders that occur naturally in southern Italy to build structures ranging from harbour walls to the Pantheon. In Britain, cement (lime mixed with ash or brick dust) was being produced artificially in commercial quantities by the early 19th century, and became a fashionable alternative to stone for facing middle-class terraced housing. Mixed with aggregate it formed a quick-setting concrete for harbour walls and workers’ cottages. Inserting iron reinforcements followed in the 1850s, making possible concrete columns and beams. It was in France where the most significant inventions were made and above all marketed, led by François Hennebique, a building contractor turned engineer who disseminated his efficient reinforcement system through a series of approved contractors across Europe and beyond. In 1895 he dispatched a senior engineer, Louis Gustave Mouchel, to erect a granary and flour mill in Swansea and to establish a London office.

The first concrete structures concealed their raw guts behind brick or stone façades, partly for good manners and partly because of building regulations. It took until the mid-1920s, with buildings such as London’s Fortune Theatre and the Wembley Exhibition, for concrete to be recognised as beautiful in Britain. In the 1930s it became a statement of forward thinking and efficiency, as at Marlborough College, Wiltshire, where the memorial assembly hall is classical and the science laboratories of exposed concrete, yet designed by the same architect, W. G. Newton. This trend became still more important in the 1950s and 1960s, encompassing almost every building type.

While new techniques permitted larger schools, taller flats and more complex factories, they could also look more interesting. Sand or pebble aggregates offered infinite variations in colours and textures, sparkling where a sliver of mica or a grainy texture caught the low British sunlight. White concrete showed a careful choice of materials, since cement naturally darkens over time. Rich board-marking was a sign of sophistication; at the National Theatre the formwork was of carefully chosen Douglas fir, each piece to be used only twice since slurry would lodge and blur the pattern of its graining. Textures could be further enhanced by brushing or hammering the concrete as it cured: large aggregate could be exposed, or a cast ribbed finish partly chipped away – effective at London Zoo’s Elephant House and South Norwood Library.

Concrete’s elemental quality suited it for churches, theatres and art galleries, offering more than an ability to bridge large spans without intervening columns. It made possible the more open, wider structures that followed new thinking in both churches and theatres that sought to throw clergy and congregations, actors and audiences, closer together. It also provided a framework for stained glass and works of art. Indeed, concrete was also a medium for art itself. When in 1957 William Mitchell and Anthony Hollaway were employed by the London County Council as its first artists, they had to work with materials that cost no more than those being used for the buildings they were decorating. Their media thus became the concrete and bricks found on site, moulded or blasted in any way possible, plus what they termed ‘rubbish’ such as broken tiles and glass.

NEW TECHNIQUES

Reinforced concrete became steadily more sophisticated. Building regulations for new materials were most rigorous in London, so the greatest innovation was generally found elsewhere in Britain. Concrete’s tensile qualities were increased with the pre-stressing or post-tensioning of steel wires through the concrete, patented in France by Eugène Freyssinet in 1929 and proven when in 1934 he rescued Le Havre’s subsiding maritime railway station. Wires were run through the mould before the concrete was poured. They could be pre-tensioned, though most were post-tensioned after the concrete had partly cured. Pre-stressing had barely reached Britain by the war but was quickly adopted in the early 1950s for large spans following its success in a bus garage at Bournemouth. As important were the arrival of 300ft (91m) high tower cranes such as Big Alphonse, imported from France by the contractors Wates for building tall flats, mainly for the LCC. Smaller cranes ran on rails, making it essential that blocks be planned in straight lines at system-built estates such as Morris Walk (demolished), Broadwater Farm and Aylesbury.

The war saw advances in pre-casting, a simpler way of producing slabs and beams than pouring concrete into timber formwork erected in situ. Factories offered better working conditions and enabled the concrete to be finished to the highest standard, as with the storey-high panels of Alton West. The results can be more beautiful than stone, since they are so precisely controlled, but are almost impossible to replicate once a building is completed. The Cement and Concrete Association opened a research centre at Wexham Springs in 1947, building a series of offices and laboratories in a landscape with fencing and sculptures to demonstrate different methods of concrete construction and finishes, adding a training college at Fulmer Grange next door in 1966. Today, the only survivor on the redeveloped site is William Mitchell’s primeval sculpture Corn King and Spring Queen, from 1964.

The forgotten boom of the 1950s was in building power stations, bringing yet more contracts to the major construction companies and seemingly infinite supplies of cheap energy with the completion of the national grid across the United Kingdom. Electricity remained cheap until the early 1970s, when coal miners’ strikes and a 300 per cent rise in oil prices brought a dramatic end to a luxury that had been taken for granted. Many council homes suddenly became too expensive to heat. Reliable electricity meant that a sealed and air-conditioned environment became possible, and houses, shops and offices could have large open plans. These could be brilliantly lit for the first time, for at last artificial lighting became reliable; cold cathode and fluorescent fittings appeared in the war and were first adopted for civilian use in the public hall over Peckham’s Co-operative store in July 1949.

Structures became larger as more functions, boiler plants and covered parking were added. The architect Owen Luder explained in 2009 that ‘because you couldn’t get steel, you used in-situ concrete as it was the only thing you could do. That meant that the big contractors were doing the foundations and building frame, then they brought in specialist sub-contractors to do the rest. This was also the beginning of prefabrication off-site, bringing things in on a separate package. The concrete was exposed because it was the structure, and you can use the shutter boarding as a finish in various ways. Contractors didn’t realise how expensive concrete was to do, and for a time it was under-priced – by the late 1960s they realised, and it became expensive.’12

Luder was referring to the large construction companies that came to the fore during the Second World War and expanded further thereafter, winning large contracts in the new towns and in town centres. When after 1953 central government subsidies for public housing focused on slum clearance, with extra grants for building tall flats, these contractors began to license building systems from France, Denmark and Sweden, where prefabricated solutions to the chronic housing shortages had already been developed. They built their own factories to cast the concrete panels and beams. By the late 1960s seven companies dominated the housing market: George Wimpey, Britain’s largest contractor; John Laing & Son and Taylor Woodrow, their closest competitors; Concrete Ltd, the largest materials firm and licensees of the Bison system developed in Dartford, Kent; Wates, housing specialists with their own methodology; Camus (Great Britain), a subsidiary of the French giants who entered the British market via Liverpool in 1963; and Crudens Ltd, a Scottish company that held the licence to the Swedish Skarne system. By the late 1960s, Laing alone were employing over 10,000 men. Many firms had connections to the Conservative Party – Keith Joseph was heir to the Bovis company and Geoffrey Rippon a director of Cubitts – but it was the Labour Government of 1964 that made a condition of financing public housing that it should be system-built. George Finch, working for the LCC and the London Borough of Lambeth, recalled that ‘you had to develop strong arguments not to use a system. Local authorities were being strongly pushed and housing committees found it hard to resist the pressure.’13

THINKING BIG

Summerson’s ‘big sneeze’ saw the younger generation blow apart the international debating shop on modernism, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne founded in 1928. After organising its tenth meeting at Dubrovnik in 1956, a group of younger architects including the Smithsons formed a breakaway organisation appropriately called Team 10. Early studies for Dubrovnik on the theme of ‘Habitat’ produced by the English contingent (the Smithsons, Stirling, Bill Howell, John Partridge, Colin St John Wilson, Peter Carter and John Voelcker) had rejected freestanding tower blocks for lower-rise schemes that huggled round new street patterns. They suggested possibilities for public housing that began to appear for real in inner London a decade later. Once central heating and motor cars became affordable for council tenants around 1960, it made sense to stretch long slabs over basement parking, creating enclosed precincts in place of the traditional street pattern. Team 10 members encouraged an international style of large units that covered a variety of functions within city centres, new towns or universities like a giant overcoat. These they called ‘mat building’, but a more common term by the 1970s was the ‘megastructure’, derived from the artificial planets of science fiction such as Larry Niven’s Ringworld of 1970.

While many architects turned to teaching and exhibition work to support themselves between building projects, in the Smithsons’ case for many years, a few made a permanent career in this growing world of pure ideas. They were liberated by not having to make their projects remotely buildable, as can be seen in the largely theoretical work of Cedric Price and particularly of the six architects associated with Archigram magazine, whose most sought-after issues adopted the look of science-fiction comics. Telegrams may be no more, but the word amalgamated with ‘architecture’ still has a buzz to it. Peter Cook, David Greene and Michael Webb came straight from college, but Warren Chalk and Ron Herron had earlier worked for the LCC, moving from schools to detail the South Bank centre where they were joined by Dennis Crompton and in 1961 met Theo Crosby, who found them work with the builders Taylor Woodrow to support their reveries. Here the ambitions of the 1960s could assume boundless possibilities, but in turn inspire what might actually be buildable. An exhibition at the ICA, Walking City, led by Herron, envisioned London remodelled with giant beetle-like structures, while Cook’s Plug-In City saw buildings as adjuncts to a network of roads and services, repurposing an old city for constant change. He and Greene reimagined the design as a shopping centre for the latter’s native Nottingham, though in fact the group’s only buildings before the 1980s were a playground in Milton Keynes and a swimming pool for the singer Rod Stewart.

Here was a background for what might have happened if more money and materials had been available. We might scoff at the idea of two motorways coursing through Brixton, south London, but Magda Borowiecka’s barrier block and George Finch’s recreation centre raised on a pedestrian walkway remind us that until 1972 these roads were expected to happen. Only the City of London had the means and political stability to see a project to its end; hence the importance of the Barbican, first planned by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon in 1955 and built between 1963 and 1982 with little wavering of purpose and no short cuts.