21,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

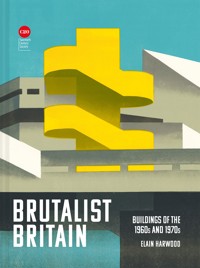

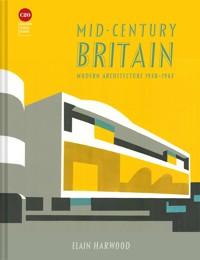

Leading expert and passionate advocate of modern British architecture Elain Harwood gives the best overview of British architecture from 1938 to 1963 – mid-century buildings. Growing in popularity and with an increasing understanding of their importance as a background to our lives, the buildings range from the Royal Festival Hall, Newcastle City Hall and to Deal Pier and Douglas ferry terminal, from prefabs and ice cream parlours to Coventry Cathedral and the Golden Lane Estate. The author writes in non-technical, layman's language about the design, architecture and also the influence of these buildings on the lives of our towns and cities. The author has arranged the huge variety of buildings into: Houses and Flats: Churches and Public Buildings; Offices; Shops; Showrooms and Cafes; Hotels and Public Houses; Cinemas, Theatres and Concert Halls; Industrial Buildings and Transport. There is an insightful introduction that places these buildings in the context of 20th-century architecture generally and globally. All fantastically photographed to make this a must have for anyone interested in our built heritage. Postwar Britain architects often saw architecture as a powerful means to improve the quality of our lives after the shadow of war. This is the fascinating story of what they built to meet that challenge. Cover illustration by Paul Catherall

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 230

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Mid-century Britain

The Festival of Britain

Private Houses and Flats

Low-cost Housing

Education

Public Buildings and Memorials

Shops, Offices and Industry

Entertainment

Transport

Places of Worship

Footnotes

Index

Picture credits

MID-CENTURY BRITAIN

Mid-century modern is a term coined in the United States to describe architecture and design from about 1940 to the early 1960s. Used only a little during that period, it became popular when in 1984 Cara Greenberg published Mid-Century Modern: Furniture of the 1950s, an example of the design world taking the lead in reviving a fashion and bestowing its nomenclature as it had with Art Deco.1 The name was quickly adopted to describe the flash hotels built along Miami’s northern shore in the 1940s and 1950s, and as quickly reduced to ‘Mi-Mo’, also referring to Miami Modern.

British architects around 1950 had their own terminology. They spoke instead of the ‘New Empiricism’ or ‘New Humanism’ to describe a gentle modernism that was simple and functional but had decorative touches. In calling her ground-breaking survey Contemporary, in 1994 Lesley Jackson revived a name used in its day for buildings and interiors considered to lack intellectual rigour, usually well-meaning public buildings designed by junior borough architects with too many contrasts of materials, colours and planes. ‘When I hear the word contemporary, I reach for my revolver,’ quipped Theo Crosby in a manifesto for the counter-movement, the New Brutalism.2 What he would have made of the term ‘Soft Brutalism’ used today for much of this architecture should perhaps remain unprinted. ‘Mid-century modern’ might be American, but it usefully describes the best design by a generation that was equally confident in architecture, furniture design and landscape, which included such international talents as Arne Jacobsen, Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames and Marcel Breuer. Yet the phrase can equally be used of more modest but dynamic symbols of post-war affluence such as cafés and ice-cream parlours. There is (inevitably) a more specific American term for this – the ‘Googie’ style, taken from the coffee shop of that name in Hollywood designed by John Lautner in 1949 and used by Douglas Haskell of House & Home magazine in 1952 to describe the futuristic shapes, day-glo colours and neon synonymous with the diners, motels and drive-ins of suburban highways. Planning legislation and limited car ownership, especially among the young, ensured such developments remained rare in Britain; a motel built at Newingreen, Kent, in 1952 was listed, yet was demolished.

One name truly describes the architecture and design of the 1950s in Britain, and Britain alone: the Festival style, a reference to the great exhibition of British culture and manufactures held across the country in the summer of 1951. It marked the evolution of modernism in a country where neo-classicism and Art Deco styles had dominated public building through the 1920s and 1930s. These had adopted many details from northern Europe, particularly Scandinavia, and so too did the gentle modernism beginning to be seen by the Second World War. If the Festival of Britain marked the high point of this style’s fashionability, it remained the dominant style into the early 1960s, surviving longest in libraries, town halls and entertainment buildings. Elsewhere it began to be refined, to become more measured and simple in its ingredients, reaching a minimal extreme with the development of curtain walling – whole facades of glass, aluminium and steel. Mid-century modern embraces all these variants. First of all, though, the use of the word ‘modern’ requires some extra explanation, taking us back further in time.

The Modern Movement

Britain saw little in the 1920s of modernism, the radical style epitomised by white boxes of reinforced concrete. It need not have been so, for the country had made early advances in concrete as well as steel-framed construction, just as its Arts and Crafts movement had looked for simplicity in the use of traditional materials and furnishings. Indeed, in his book on modernism first published in 1936, Nikolaus Pevsner claimed William Morris as its first pioneer.3 Nevertheless, it would be possible to write a parallel account of early 20th century architecture in the English-speaking world, especially the United Kingdom, which focused solely on classical buildings. A genre harking back to the traditions of Sir Christopher Wren seemed suited to the head of the world’s largest empire and responded to building regulations that favoured conservative construction methods; it was encouraged by the importation of Beaux-Arts doctrines from France to the growing schools of architecture, notably at Liverpool University, which in 1894 introduced the first course to be recognised by the Royal Institute of British Architecture (RIBA).

In the 1920s British architects found inspiration in northern Europe and especially Scandinavia. Denmark and Sweden also followed a broadly neo-classical tradition at this time, with Philip Morton Shand coining the phrase ‘Swedish Grace’ to describe the stripped-back refinement found in that country. Its builders developed distinctive brick bonds and diaper patterns, projecting headers being a particular favourite, which they combined with render and coloured tiles. Monopitch roofs were practical in heavy snowfalls. The Netherlands offered an extensive range of more modern housing models, from low-rise estates by J.J.P. Oud to tall flats by Johannes Brinkman and Willem van Tijen; Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya used their student prizes to visit Rotterdam in 1945 ahead of designing Churchill Gardens. Willem Dudok’s new town of Hilversum became a source for many public buildings. Herbert Tayler knew the Netherlands through his Dutch mother, but was also impressed by Ernst May’s working-class terraces in Frankfurt, seen on a student trip with his partner David Green in 1930.

The development of reinforced concrete was taken forward in Europe and then America rather than Britain. The reinforcement of concrete with an embedded steel mesh provided some tensile strength and a greater efficiency in compression, and was first patented in Britain under franchise by a French company, Hennebique. The result in 1897 was an enormous flour mill for Weaver & Co. in Swansea. By 1914, architects in central Europe were showing that steel, glass and concrete could produce industrial architecture of great elegance, exemplified by Gropius’s Fagus Factory at Alfeld near Hanover completed that year. Meanwhile, in Vienna, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos and others were designing prestigious offices and executive houses without mouldings, producing geometric shapes with sheer planes as facades. After 1918, these clean forms, acknowledging only the basic classical proportions to inform new ways of interspersing solids and voids, suggested a stylish, healthier way of living – one without excess or the trappings of past regimes now discredited. This seemingly simple architecture also offered possibilities for cheap housing and a range of public buildings, addressing a social agenda of growing importance as left confronted right in the straitened times that followed the Great War and Russian Revolution.

Housing at Römerstadt, Frankfurt: Ernst May, 1928.

Bauhaus, Dessau: Walter Gropius, 1924.

The underlying theories of practicality and propriety (Sachlichkeit) and the spirit of the age (Zeitgeist) were largely published in German, although Dutch, Czech, Swiss, Russian and French architects contributed to the movement. While it established a course teaching architecture only belatedly, a centre for the movement was the Bauhaus, the art school in Weimar renamed by Gropius in 1919 and moved by him in 1924 to Dessau, some two hours south of Berlin. A meeting point for artists and designers from across Europe where the planes of Dutch de Stijl met the expressive forms of Russian constructivism, the Bauhaus also encouraged rigorous thinking from first principles and collaborations between architects and between them and other disciplines on an equal footing. No fewer than 17 architects contributed to the Weißenhofsiedlung, a housing estate in Stuttgart built as an exhibition for the Deutscher Werkbund in 1927. Of the 21 buildings erected using flat roofs and generally white exteriors under the direction of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 11 have survived. They include three houses by Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), in which he demonstrated the ‘five points’ that he felt underlay all modern architecture: the unmoulded column or ‘piloti’, a free plan, free facade, strip windows and flat roof. The requirements presumed a reinforced concrete frame supported on the pilotis, though in practice the outside walls – whether of concrete or brick – continued for a time to take much of the load. The following year, 1928, saw the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) founded at La Sarraz in Switzerland as a forum for debating ideas on modern architecture that continued until 1959, charting the wider aspirations of the mid-century towards planning and urbanism, and eventually sealing the style’s eclipse.

Britain had little building in this modern style before 1930. The first building in the style is generally acknowledged as New Ways, Northampton, a house of rendered brick from 1925–26 by the German architect Peter Behrens for W.J. Bassett-Lowke, whose career as a model engineer brought him in close contact with designers and toy manufacturers from that country. More telling was High and Over, erected in 1929–30 on the hill above Amersham, Buckinghamshire, by Amyas Connell, a New Zealander who had come to London with his friend Basil Ward determined to win the Prix de Rome in classical architecture only to be seduced by the work of Le Corbusier. Many of the earliest exponents of modernism in Britain came from the Commonwealth, with Raymond McGrath from Australia and Wells Coates from Canada showing, like Connell and Ward, the benefits of travel and a broader education. They formed the core of the Twentieth Century Group in 1930 and the Modern Architecture Research (MARS) Group in 1933, which affiliated itself to CIAM. But when in 1932 Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson published The International Style alongside an eponymous exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, they included from Britain only Joseph Emberton’s Royal Corinthian Yacht Club at Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, opened in 1931.4

The rise of fascism forced an exodus of modern architects to the Americas, Palestine, Africa and beyond. The westwards shift of CIAM, which left Le Corbusier in Paris as its dominant force, was exemplified by the career of a fellow Swiss, its secretary Sigfried Giedion. Born in Prague and educated in Vienna and Munich, from the late 1930s to the late 1950s he taught at Harvard University alongside Josep Lluís Sert, whose own exile took him from Barcelona through Paris to the United States. London was an important stopping point for many architect migrants. Some, like Berthold Lubetkin from the Soviet Union, settled permanently and supported later refugees such as Peter Moro, whom he employed as a specialist in staircases at his second block of flats in Highgate, Highpoint II. This block has a wider structural significance, for while the earlier Highpoint I of 1933–35 closely resembled the Weißenhofsiedlung in its structure (and was admired by Le Corbusier), at Highpoint II in 1936–38 the Danish émigré engineer Ove Arup made a braced frame from the internal cross walls and floor plates. This open-ended structure can be likened to a wine rack, a series of cubes with no front or back; because the central part of the main elevation carried no load Lubetkin could introduce double-height windows towards Highpoint’s gardens. Arup refined this ‘box-frame’ in the 1940s, but even the simplest cross-wall construction made possible the lighter, open facades found in all post-war buildings from terraced housing to office towers.

The émigré architects Erich Mendelsohn, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer produced a handful of buildings in Britain before finding greater opportunities in the United States. Mendelsohn created the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, opened in 1935, and Gropius a school at Impington, near Cambridge, a light, largely single-storey building of brick very different to the futuristic Bauhaus. To gain work permits, many émigrés formed partnerships with British nationals, bringing experience and kudos to a younger generation. These included F.R.S. Yorke, who had already promoted modernism – and his own career – with a book, The Modern House, which went through six editions.5 In 1935–37, he formed a partnership with Marcel Breuer that saw the building of a white concrete summer house on pilotis at Angmering-on-Sea, Sussex, and alterations to Wells Coates’s Lawn Road flats.

Weißenhofsiedlung, Stuttgart: houses by Le Corbusier, 1927.

Mid-century Modernism

By the late 1930s these architects had learned that concrete and flat roofs were less flexible than they had hoped. Yorke’s assistant Randall Evans recalled to the historian Alan Powers the problems of threading ducts and services through a roof slab at a house in Lee-on-the-Solent, Hampshire. ‘Let’s make a New Year resolution – no more concrete houses,’ they had declared.6 In 1936 Breuer produced a temporary pavilion of Cotswold stone for the furniture retailers P.E. Gane, exhibiting at the Royal Agricultural Show in Bristol. Raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Yorke understood Cotswold building traditions, but for Breuer international influences were more important, including Le Corbusier at the Villa Mandrot in 1931, Pavillon Suisse (1930–32) or in his own apartment in the Rue Nungesser-et-Coli (1934), where he combined natural stone with a concrete frame. A little brick terrace at Stratford-upon-Avon, built in 1938–39 with stone end walls and a monopitch roof, shows Yorke turning the synthesis into a new British modernism.

How British architecture might have evolved but for the Second World War can be seen at the Impington school and in a series of houses built in the late 1930s. These include Overshot, near Oxford, by Godfrey Samuel and Valentine Harding from 1937, faced in brick and timber under a shallow-pitched copper roof; three brick houses by Mary Crowley of 1936 at Tewin, Hertfordshire, for her family and a friend, all with monopitch roofs that acknowledged her great love of Danish architecture; and Moro’s eclectic house at Harbour Meadow, Sussex, completed in 1940. The most intriguing is perhaps Brackenfell in Cumbria, a small house and studio for an artist and collector built in 1937–38 by Leslie Martin and Sadie Speight that married brick, tile and local stone with expressive shapes and massing drawn from Russian constructivism, explored first hand through the couple’s friendship with another refugee, Naum Gabo. This was an early example of a building also designed as a repository for art, which became a feature of the early 1950s. Many of the younger architects, including Samuel, Harding and Crowley, had trained at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, where modernism came to dominate teaching from the mid-1930s and where in 1936 a new principal, Eric A.A. Rowse, allowed the students to collaborate in groups on larger projects with time to explore social, historical and planning issues rather than simply produce designs. The move encouraged the students to become still more politically motivated, drawing them initially into conflict with the AA’s management, but after the war it became an integral part of the school’s working as well as the beginnings of many professional partnerships.

Walter Segal, who arrived in London from Germany in 1936, sought ‘a natural architecture’ and this shift can be seen in many northern climates. Frank Lloyd Wright experimented with traditional materials in the service of modernism from the mid-1930s, famously at Fallingwater, while Alvar Aalto embraced the Finnish landscape and climate with a collage of stone, timber, steel, concrete and render at the Villa Mairea of 1938–39. Houses at Lincoln, Massachusetts, by Gropius and Breuer heralded a new style more responsive to nature and place by marrying local rubble walling with timber framing and painted boarding. It was an assimilation of New England traditions and the latest in American open planning with their experiments in (old) England; its promotion by Sigfried Giedion as a ‘new regionalism’ was timely for émigrés seeking to show their commitment to a new country. Some of these houses were illustrated in the Architectural Review in November 1939, along with ones by Richard Neutra and William Lescaze – the latter with a flying canopy supported on two sharply angled columns. It was, however, Breuer’s own house at Lincoln, with its double-height living space and contrasting materials, which offered the clearest model for young British architects. Gropius made group working fashionable when he founded the Architects’ Collaborative with his graduate students in 1938.

In Sweden, Gunnar Asplund turned from classicism to modernism when in 1930 he curated the Stockholm Exhibition, its temporary buildings adopting a functional style locally called funkis, enlivened by colour, pattern and works of art. Imaginative sculptures by Carl Milles became a feature of the city’s streets and quaysides, preferred to commemorative representations of past dignitaries. This change was followed in 1932 by the election of a social democratic government, heralding an innovative welfare state based on insurance programmes for the sick, elderly and unemployed (modelled on David Lloyd George’s reforms in Britain), partial nationalisation and decent housing. The development of an architectural expression for this democratic socialism made the country particularly appealing to young, left-leaning architects from Britain.

Brewery Terrace, Stratford-upon-Avon: F.R.S. Yorke, 1938–39.

Post-War Building

Construction in Britain, so slow through the 1920s and 1930s, picked up from 1936 but halted again with the outbreak of war in September 1939. The Ministry of Works and Buildings assumed control of building materials, especially timber, and continued similar measures into peacetime. This rationing was a bitter blow to the ambitions of the Labour Government elected in July 1945, the first to win a clear majority. Its mandate to build a more equitable Britain, supported by decent national insurance and healthcare, with good homes and schools, was based on the principles set out by William Beveridge in a government report of December 1942 that was read by a remarkable number of people. Aneurin Bevan, the dynamic young minister responsible for health and housing, was anxious to build. But supplies of softwoods from Scandinavia were decimated by a drain on Britain’s dollar reserves in July 1947, following the end of an American loan, although luxurious hardwoods from the Empire remained available because they could be bought with sterling. Controls on the profits of developing land or ‘betterment’, introduced in 1947 by the Labour Government, delayed the building of private houses and commercial offices – although it did not stop entrepreneurs from buying up sites ahead of the repeal of the controls by the Conservatives, who returned to power in 1951. The new government retained a system of licensing until November 1954, so that the limited supplies were directed towards schools, public housing and industry. This did not relieve the slow pace of most public building, which frustrated the efficacy of progressive legislation on new towns, planning and the National Health Service. More effective was the building of hundreds of new power stations and deep mines to meet rising demand for electricity and coal following Labour’s nationalisation of the power and transport industries.

The shortages of brick and timber encouraged architects to be creative. The RIBA promoted prefabrication in an exhibition, Rebuilding Britain, at the National Gallery in February 1943, followed by ones on Swedish factory-made housing and new American townships in 1944. Timber houses were imported from Sweden in 1945–46, but of greater impact was the work of the Burt Committee and an Experimental Building Department that authorised the building of thousands of two-storey houses using unconventional materials, many of which survive today. Between 1946 and 1951 the British Iron and Steel Federation erected 31,320 houses to a design by Frederick Gibberd that used sheet-steel panels as a distinctive cladding to lighten the upper storeys. Estates of these houses were commonly termed ‘tin towns’. Other manufacturers used precast concrete beams or slabs, sometimes with brick end walls; of these, Cornish Unit housing using the waste from china clay manufacture can be most easily identified because the upper floor is set in a mansard roof.

The quintessential ‘prefabs’, however, were the 156,623 small bungalows built under the Temporary Housing Act of 1944 after Sir Winston Churchill promised that half a million new homes would be built as soon as war ended. Willing inventors experimented with plywood, concrete and asbestos sheeting, producing 11 approved variants after the government’s steel prototype – exhibited at the Tate Gallery in May 1944 – was found to be too expensive. For architects brought up on Meccano, wartime innovations and American experiments in packaged housing (by Konrad Wachsmann, Walter Gropius and Buckminster Fuller), these were exciting times. By 1948 bricks were back in supply and the cost of transporting precast units from several suppliers was competitive only for larger structures, making schools the one outstanding success of the prefabrication story. Large numbers of primary schools were needed quickly for new estates and to meet the baby boom of the mid- to late 1940s. Hertfordshire County Council’s programme best captured the mood of the times, a development from first principles that brought together artists, engineers and manufacturers to create a bright, informal environment designed to stimulate the small child.

Sweden and Denmark promoted their brand of architecture and interior design aggressively after the war, publishing extensively in English. The Architectural Review devoted its issue of November 1948 to Danish architecture, which it later also published as a book, but Sweden attracted a greater number of architect-travellers, drawn to its social programmes and exhibition work as well as good design. Its neutrality in the Second World War ensured that its belated industrialisation and related housing programme continued through the conflict. Robert Matthew, chief architect at the London County Council, studied prefabrication and the concert halls recently built at Gothenburg and Malmö. However, its appeal was greatest among students and young graduates: Trevor Dannatt recalled the joy of visiting a country free of rationing and found a similar cornucopia in its architecture and design. Oliver Cox, Graeme Shankland and Michael Ventris lived in Stockholm for two months in 1947, which informed their work on housing and schools, while Ralph Erskine had already settled there permanently.

In the absence of building in Britain, and with the continued rationing of foodstuffs, clothes and appliances, exhibitions promising better days ahead assumed a great importance. Many architects, including Basil Spence, specialised in their design. An exhibition of new manufactures held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1946, Britain Can Make It, was popularly renamed ‘Britain Can’t Have It’, since most new goods were directed to the export market in the vain hope of supporting the ailing pound. Devaluation in 1949 did little to relieve the austerity, made worse with the outbreak of the Korean War a year later. Fortunately, the greatest exhibition of them all – the Festival of Britain – was too advanced to cancel, although its budget was cut by a quarter.

Swedish prefabs, Auckley, Doncaster, c. 1948.

The Festival of Britain

The idea of commemorating the Great Exhibition of 1851 was first suggested by the Royal Society of Arts in 1943 and revived in 1945 by Gerald Barry, editor of the News Chronicle, as a great trades and cultural exhibition.7 A showcase for British advances in science, manufactures and the arts, it marked the country’s move from the centre of an empire to focus on technology and innovation. The name ‘Festival of Britain’ was coined by Prime Minister Clement Attlee and Herbert Morrison, Labour’s deputy leader. Yet, while the event was closely associated with Labour and Morrison’s old stamping ground of the London County Council, which provided the three main London sites and built the Royal Festival Hall, its style was determined by Gerald Barry as director general and Hugh Casson as director of architecture. Casson (1910–99) typified a generation of architects trained in the 1930s whose career had been cut short by the war, but who now found a belated chance to build – and with a freedom to do much as they liked. A core group had worked with Casson on an exhibition for the MARS Group in 1938, and he asked friends he could trust to take on the central buildings and open spaces. By 1951 it seemed that nearly every architect in London was working on the Festival to meet its 3 May deadline.

Having so many designers led to a great complexity of detailing, despite simple materials and an intended life of just five months for the main exhibition on London’s South Bank. The tight site was very different from the open plain of the Champ de Mars used for exhibitions in Paris, yet a twisting circulation route controlled by changes in levels, landscaping and water features worked to its advantage. It personified the revival of the picturesque movement in buildings and landscape which the editors of the Architectural Review (of whom Casson was one) had promoted during the war as a symbol of national identity and a contrast to the straight lines and neo-classicism of totalitarianism, whether of the left or right. Articles on Capability Brown and the English public house had run alongside those on new architecture in Sweden and Brazil. By the late 1940s the movement had evolved into what the magazine’s owner Hubert de Cronin Hastings had christened ‘townscape’, the picturesque weaving together of variously shaped buildings, hard landscaping and street furniture in towns old and new, generally to be explored on foot. The idea was taken forward by his art editor, Gordon Cullen, with articles in the Architectural Review that in 1961 were collated as a book, also called Townscape.

There were affinities between the Festival and the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, in its relationship to water and constructivist juxtapositions, unified colour palette and lettering. A still closer association was with the New York World’s Fair of 1939–40, which featured a circular exhibition building, the Perisphere, and a needle-like landmark tower, Trylon. The Festival of Britain had respectively the Dome of Discovery by Ralph Tubbs for its main exhibitions and Skylon, a cigar-like structure supported on a cat’s cradle of cables devised by Powell and Moya with the engineer Felix Samuely. Its ebullient style was most clearly seen in the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion, by Robert Russell and Robert Goodden, probably from an idea by Casson (he certainly thought of the name). It was a whimsical celebration of British character based on the heraldic supporters of its coat of arms, one standing for ‘realism and strength’ and the other ‘fantasy, independence and imagination’.8 They were displayed as traditional corn dollies, while giant figures represented the law, church and Alice in Wonderland’s White Knight, set under a flight of plaster doves issuing from a wicker cage and symbolising liberty.

The Festival was the last great event before television became widely available, so people had actually to visit the South Bank to appreciate it. People braved the long queues and puzzling displays to enjoy the experience of being in a modern village in the heart of London, where the Gothic gables of Whitehall Court across the river added to the sense of folly. It came to life at night when, lit by tiny bulbs set in the concourse paving, hundreds of dancers defied the wet weather to foxtrot in their overcoats. The unseemly haste of the exhibition’s demolition in early 1952 ensured its mythical status. The LCC were persuaded to clear the site quickly in the expectation that its development as a cultural centre, begun so promisingly with the Royal Festival Hall, would continue. Instead the government reneged on the deal and the land stood empty for a decade, when lines of trees and the imposition of covenants over certain views – as well as much larger buildings – ensured that the Festival’s happy intricacy was not repeated.

The South Bank’s centrepiece architecturally and culturally was the Royal Festival Hall, the one permanent building. A replacement for the bombed Queen’s Hall, home of the London Proms, it reflected a revival of classical music in the wake of wartime concerts and radio broadcasts, seen too in the Aldeburgh, Cheltenham, Edinburgh and Malvern festivals, the Third Programme (now Radio 3) and the Arts Council – all launched in the late 1940s. But while there was little save praise for the RFH’s auditorium and the great foyers that surrounded and underpinned it, the elevation with its patterns of little windows and mix of materials raised questions – already voiced internationally in a series of articles by Sigfried Giedion – about whether the mid-century modern style had the gravitas for a really major public monument.