6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This collection of essays reprints previously published writings about Trinity College Cambridge's most celebrated writer, Lord Byron, for the bicentennial commemoration of his death on 19 April 1824. Bringing together diverse contributions from a series of scholars, three of them fellows of Trinity College, it explores various aspects of Byron’s life and writing. The collection draws out the relationships between ‘memorials, marbles and ruins’, themes always prominent in his thinking and feeling.

The earliest essay reprinted here dates from the bicentenary of Byron’s birth in 1788. Thirty-six years and two centuries later, this collection honours a figure of enduring, complex significance, with whom Trinity College is proud to be associated. It will be of value to scholars and students of Byron, as well as those interested in his life, in the bi-centenary year of his death.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

BYRON AND TRINITY

Byron and Trinity

Memorials, Marbles and Ruins

Edited by Adrian Poole

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

©2024 Adrian Poole (ed.). Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapter authors or their estate.

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Adrian Poole (ed.), Byron and Trinity: Memorials, Marbles and Ruins. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2024, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0399

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Further details about CC BY-NC licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Any digital material and resources associated with this volume will be available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0399#resources

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80511-278-5

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-279-2

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80064-280-8

ISBN Digital eBook (EPUB): 978-1-80511-281-5

ISBN Digital (HTML): 978-1-80511-283-9

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0399

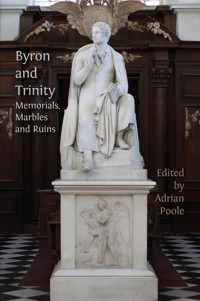

Cover photo: Statue of Lord Byron by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. Photograph by James Kirwan, courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Cover design by Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

Contents

Acknowledgements

About the Contributors

List of Illustrations

Foreword

Adrian Poole

1. Lord Byron and Trinity: A Bicentenary Portrait

Anne Barton

2. Pretensions to Permanency: Thorvaldsen’s Bust and Statue of Byron

Robert Beevers

3. On the Statue of Lord Byron by Thorwaldsen in Trinity College Library, Cambridge

Charles Tennyson Turner

4. Poets and Travellers

William St Clair

5. Byron, Stephens and the Future of Ruins

Adrian Poole

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Warm thanks are due to the colleagues who have helped bring this book to fruition including Nicolas Bell, Marc Gotthardt, Anne McLaughlin, Bill O’Hearn, Anne Toner, Fernanda Valencia, and Paula Wolff. I am particularly indebted to Nicolas Bell, the Librarian, for his assistance with the illustrations, and to Alessandra Tosi at Open Book Publishers, for the alacrity with which she welcomed the proposal. And special gratitude is owing to David Manns, Trinity alumnus, whose generous donation has made this publication possible.

For permission to reprint the chapters that make up this volume, we are grateful to the following: the executors of Anne Barton’s Estate for ‘Lord Byron and Trinity: a bicentenary portrait’, Trinity Review (1988); Liverpool University Press for Robert Beevers, ‘Pretensions to Permanency: Thorvaldsen’s Bust and Statue of Byron’, Byron Journal (January 1995); David St Clair for William St Clair, ‘Poets and Travellers’, Ch. 17 in Lord Elgin and the Marbles: the controversial history of the Parthenon Sculptures, 3rd revised edition (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998); and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for Adrian Poole, an earlier version of whose text was published under the title ‘Byron in Yucatán: War and Ruins’, in The Influence and Legacy of Alexander von Humboldt in the Americas, edited by María Fernanda Valencia Suárez and Carolina Depetris (Merida: UNAM, 2022).

About the Contributors

Anne Barton (1933–2013)was an eminent Shakespeare scholar and literary critic. Her most celebrated book Shakespeare and the Idea of the Play, adapted from her doctoral thesis at Girton College, Cambridge and published in 1962 under her former name Anne Righter, looked at Shakespeare’s historical and theatrical context to examine his relationship with plays, actors, and the audience. Some of her other publications include Ben Jonson, Dramatist (1982), The Names of Comedy (1990), and Byron: Don Juan (1992). Barton was a distinguished academic, holding positions as a Professor of English at Cambridge University and Fellow of Trinity College. She was also the first woman fellow at New College, Oxford where she taught for ten years. In 1991, she was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Robert Beevers (1919–2010)was elected Director of Regional Tutorial Services at the Open University (OU) at its establishment in 1969. As one of the university’s ‘founding fathers’, Beevers played a critical role in creating the university’s tutor and counsellor system as well as the regional study centres that function outside of its headquarters at Milton Keynes. Beyond his work at the OU, Beevers wrote a biography of British urban planner and social reformer Ebenezer Howard entitled The Garden City Utopia (1988). In retirement, Beevers published The Byronic Image: The Poet Portrayed (2005), which analyses portraits of the poet.

Charles Tennyson Turner (1808–1879) was an English poet and elder brother of Alfred Lord Tennyson. The two attended Trinity College, Cambridge together. After graduating, Turner pursued a life in the church―acting as the vicar of Grasby, Lincolnshire from 1836 until his death. Influenced by Byron at an early age, Turner published a considerable body of poems, writing a total of 350 sonnets over the course of his life. Some of his more notable publications include Sonnets, Lyrics and Translations (1873) and, co-authored book with his brother, Poems by Two Brothers (1827).

William St Clair (1937–2021)worked as a civil servant in the Treasury for many years before proceeding to Fellowships at All Souls, Oxford, then Trinity College, Cambridge, and finally the Institute of English Studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London. His passion for history motivated him to publish Lord Elgin and the Marbles in 1967, a pioneering study of the controversial acquisition of the Parthenon Marbles. In the book’s third edition (1998), St Clair exposed how attempts to whiten the Greek relics by the British Museum led to their damage. Equally invested in the world of literature, St Clair published books and articles on the genre of British biography, on writers of the Romantic period, most notably Byron, and in his massive study, The Reading Nation, on the history of books. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1992. His belief in open-access publishing led him to co-found Open Book Publishers in 2008; he acted as its Chairman until his death.

Adrian Poole (1948– )is an Emeritus Professor of English Literature at Cambridge University and Fellow of Trinity College. His research interests include comparative tragedy, prose fiction, and the impact of Shakespeare on English literature. In 2022, he won the Modern Language Association Prize for his scholarly edition of Henry James’s novel The Princess Casamassima, part of The Cambridge Edition of the Complete Fiction of Henry James.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 0.1

Anne Barton’s memorial brass in the Trinity College Ante-chapel. Photograph by Adrian Poole.

Fig. 1.1

The statue of Sir Isaac Newton in the Trinity College Ante-Chapel, by Louis-François Roubiliac (1755).Photograph by Adrian Poole.

Fig. 1.2

The memorial bust of Thomas Jones, Byron’s tutor, inthe Trinity College Ante-Chapel, by Joseph Nollekens (n.d.). Photograph by Joanna Harries, courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Fig. 2.1

Bertel Thorvaldsen, George Gordon Byron, original plaster model of the bust of Byron (April–May 1817). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/A257.

Fig. 2.2

Bertel Thorvaldsen, George Gordon Byron, marble bust of Byron (1824). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/A256.

Fig. 2.3

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument for George Gordon Byron, pencil sketch of Byron statue (1830). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Helle Nanny Brendstrup, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/C352.

Fig. 2.4

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument for George Gordon Byron with the Relief the Genius of Poetry on the Plinth, pencil sketch of Byron statue and relief for the plinth (1830–31). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/C350r.

Fig. 2.5

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Monument to George Gordon Byron, full-size plaster model of statue of Byron (May 1831). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/A130.

Fig. 2.6

Bertel Thorvaldsen, statue of Byron in the Wren Library, showing the owl of Minerva and the skull as memento mori. Courtesy of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Fig. 2.7

Photograph of the Byron statue shortly after its installation in the Wren Library in 1845. Courtesy of Trinity College, Cambridge (Add.PG.13[5]).

Fig. 5.1

Adrian Poole and other tourists at Cobá, Mexico, November 2018. Photograph by Margaret de Vaux.

Foreword

Adrian Poole

©2024 Adrian Poole, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0399.00

This collection of essays reprints some writings about Lord Byron, the most celebrated writer to have passed through Trinity College, Cambridge, for the bi-centennial commemoration of his death on 19 April 1824. It also contains a full bibliography of primary and secondary sources cited. Links to openly available primary resources, wherever available, have been added to the references for ease of access.

Three of the essays are by Fellows of the College: Anne Barton (1933–2013), who wrote a commemorative piece for The Trinity Review on the bicentenary of Byron’s birth in 1988;1 William St Clair (1937–2021), whose chapter on ‘Poets and Travellers’ in his book on Lord Elgin and the Marbles (3rd revised edition, 1998) is centred on Byron; and Adrian Poole (1948– ), whose essay on Byron and John Lloyd Stephens, the American traveller credited with the ‘discovery’ of the Mayan ruins in Central America, reflects on the legacy of the poet’s preoccupation with ruins. The fourth is by Robert Beevers (1919–2010), who describes the process by which the great statue of Byron by the Danish sculptor, Bertel Thorvaldsen, ended up in the Wren Library. Associated with this is the sonnet ‘On the Statue of Lord Byron’, written by Charles Tennyson Turner (1808–1879), elder brother of the more famous Lord Alfred.

The volume’s sub-title makes a certain claim for its coherence in the relations between ‘memorials’, ‘marbles’ and ‘ruins’, in so far as these subjects entail a continuity essential to Byron’s own thinking and feeling. Important scholarly and critical work has been done on these aspects of his life and writing, including his life-in-writing, much of it post-dating the essays reprinted here.2Nevertheless the present collection represents a modest means of honouring a figure of enduring, complex significance, of whose association with Trinity the College is proud. Given the large margin by which Byron failed to be a model student, he would have been astonished.

Not for the first time: Anne Barton recalls the ovation with which the author of Childe Harold was greeted by Cambridge students at the Senate House in 1814. But to borrow a famous saying from Shakespeare, while ‘the whirligig of time brings in his revenges’,3 it also prompts reflection on all the other challenges and opportunities with which it is freighted. It makes us consider how many words we need that begin with the prefix ‘re-’, including remembrance, reconciliation, reparation, restoration, renovation. And how complex it may be to make them real. Which is one reason, among many, why we still need to read Byron.

Fig 0.1 Anne Barton’s memorial brass in the Trinity College Ante-chapel. Photograph by Adrian Poole.

1 Anne herself has a commemorative plaque in the Ante-Chapel (see Fig. 0.1), that notes her eminence as a critic not only of Shakespeare and Jonson, especially their comedies, but also the poetry of ‘our own Byron’: OPERA SHAKESPEARIANA ET JONSONIANA PRAESERTIM COMICA NECNON BYRONIS NOSTRI CARMINA

2 On the visual commemoration of Byron, for example, see Geoffrey Bond and Christine Kenyon Jones, Dangerous to Show: Byron and His Portraits (London: Unicorn, 2020), pp. 76–84, which includes some valuable commentary on the Thorvaldsen statue, and some details not included in Beevers’s article.

3 Feste’s words in Twelfth Night, Act 5, scene 1.

1. Lord Byron and Trinity

A Bicentenary Portrait1

Anne Barton

©2024 Anne Barton, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0399.01

When this year’s Clark Lecturer,2 Jerome McCann, slyly called Lord Byron ‘Trinity’s most adorable pet’, a frisson of uncertainty rippled through the audience at Mill Lane. Suddenly, two possible meanings of the adjective ‘adorable’ were in collision: ‘worthy of reverence and honour’, the original sense, forced up against the more modern signification ‘charming, personally lovable and attractive’. For a moment, everyone in the room appeared to be trying to decide in which sense Byron might be adorable––or was it neither, or both? With no other Trinity poet, whether Marvell, Cowley, Dryden, Tennyson, or any of the rest, could such a dilemma arise. Assessments of Byron, on the other hand, in this bicentenary year of his birth, remain both contradictory and oddly personal and intense, as though this man had died only recently, rather than one hundred and sixty-four years ago. Nor has it proved possible to divorce the life and personality from the work.

For the young Byron’s long-suffering tutors at Trinity, the case was rather different. What they had on their hands for three scattered University terms, beginning in Michaelmas 1805, must have seemed in no sense ‘adorable’: a moody, extravagant, high-handed young man bitterly disappointed to be at Cambridge rather than Oxford with most of his Harrow friends. He was temporarily consoled by finding himself the possessor of ‘superexcellent rooms’3 (probably, as Robert Robson has suggested, I1 Nevile’s Court),4 where freed from the surveillance of a devoted but exasperating mother, he could begin to run himself seriously into debt. He also fell in love (‘a violent, though pure love and passion’)5 with one of the choirboys in the chapel. The Christmas vacation took Byron to London and there, despite remonstrances from Trinity, not to mention the threat of disciplinary action from the Court of the Chancery, of which he was a ward, he lingered for months, returning to Cambridge only in the summer term. He brought back with him an enlarged acquaintance with London bawds, and also with professional boxers, jockeys and fencing masters, low tastes for which his tutor Thomas Jones unavailingly reproached him. He would be engaged, before long, in an altercation with the Mayor of Cambridge, who took a dim view of Byron’s proposal to establish his fencing-master permanently in the town.

At the end of term, Byron vanished again, this time for a year. His fine rooms, re-allocated to Charles Skinner Matthews, another undergraduate, were still overflowing with Byron’s belongings and the Senior Tutor felt obliged to issue a nervous caution to the new occupant, ‘for Lord Byron, Sir, is a young man of tumultuous passions’.6 When the ogre re-appeared, however, late in June 1807, to remove them, having announced his intention of abandoning Trinity for good, he made no complaint but after renewing acquaintance with old friends, and making several new ones––including Matthews himself––decided abruptly to give Cambridge another try. Byron was now nineteen. During his year of truancy, the fat, idle, relatively unsophisticated youth the college remembered had been transformed. He had been in and out of a great many beds, had just published a collection of poems and, although there was nothing he could do about his congenital lameness, the purposeful shedding of several stone in weight had released from captivity a slim young man of arresting physical beauty. Just in case he might fail, nonetheless, to attract attention, Byron came back into residence for the Michaelmas term 1807 accompanied by a tame bear. Trinity’s statutes had long prohibited undergraduates from bringing their dogs into college, but the imagination of the authorities had not encompassed the need to fend off bears.

Byron’s reply to urgent tutorial enquiries about what he meant to do with the beast was that ‘he should sit for a Fellowship’.7 (He was later to pretend, in the postscript to the second edition of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, that only ‘the jealousy of his Trinity contemporaries prevented him from success’.)8 It was a joke with a cutting edge. Although Byron’s tutor Jones had successfully pressed, some years before, for fellowship elections to be conducted openly rather than in private, they were still susceptible to charges of favouritism and abuse. As a nobleman, moreover, Byron regularly dined in Hall with the fellows of Trinity. His impression of them as a group he had communicated earlier in letters written from Cambridge: ‘Study is the last pursuit of the society; the Master eats, drinks, and sleeps, the fellows drink, dispute, and pun’. Their pursuits, he claimed, were ‘limited to the Church,––not of Christ, but of the nearest benefice’.9 In ‘Thoughts Suggested by a College Examination’, a satirical poem published in his collection of 1807, Hours of Idleness, he made his contempt more public:

The sons of science, these, who thus repaid,

Linger in ease, in Granta’s sluggish shade;

Where on Cam’s sedgy banks supine they lie,

Unknown, unhonour’d live,––unwept for, die;

Dull as the pictures, which adorn their halls,

They think all learning fix’d within their walls;

In manners rude, in foolish forms precise,

All modern arts, affecting to despise;

Yet prizing Bentley’s, Brunck’s, or Porson’s note,

More than the verses, on which the critic wrote;

Vain as their honours, heavy as their Ale,

Sad as their wit, and tedious as their tale,

To friendship dead, though not untaught to feel,

When Self and Church demand a Bigot zeal. […]

Such are the men, who learning’s treasures guard,

Such is their practice, such is their reward;

This much, at least, we may presume to say;

The premium can’t exceed the price they pay.10

If, as Hobhouse later asserted,11 Byron was indeed the undergraduate that the great classical scholar Porson, Regius Professor of Greek at Trinity, once tried to assault with a poker, the attack was not entirely unprovoked.

When Byron included ‘Thoughts Suggested’ in the first edition of Hours of Idleness, he believed he had finished with Cambridge forever. He was a little nervous about the poem, all the same, especially after his own unexpected return to ‘Granta’s sluggish shade’. On the 20 November 1807, he wrote from Trinity instructing his publisher Ridge to omit it from the second edition. But, by 14 December, as term drew to a close, he had changed his mind, not only countermanding the November deletion, but adding four new lines, those beginning ‘Vain are their honours...’ to the original. It was one of the first examples of what was to become Byron’s characteristic reluctance to let go of a poem even after it had been published, the urgent need to carry forward with his own life what he had written months, or even years, before. In this instance, the accretion signalled another decision, this time irrevocable, to abandon Cambridge. Between Christmas 1807 and the spring of 1816, when he was (or felt himself) driven from England by the scandal surrounding the break-up of his marriage, Byron would return several times to visit or offer support to friends. His official connection with the University came to an end, however, in July 1808, when he finally took that MA which Cambridge, in his case, was most reluctant to award. ‘The university still chew the Cud of my degree’, he informed his friend Hobhouse (who was still at Trinity) in March of that year: ‘please God they shall swallow it, though Inflammation be the Consequence.’12

Ironically Byron owed his MA to precisely that academic venality and corruption about which he was so scathing both in letters of the period and in his satirical Cambridge poems. It was his bare three terms of residence which made the degree problematic, not the fact that he had never taken an examination nor, so far as is known, bothered to attend lectures. In 1787, Byron’s tutor Thomas Jones had made the radical proposal that noblemen and wealthy fellow-commoners should be obliged to take examinations just like financially dependent undergraduates, the pensioners and sizars. The Grace was defeated in the Senate House. Like other peers, Byron received his degree in exchange for going through a few minutes of whispered ‘disputation’ with his tutor in the Senate House, and handing the latter, (no longer, at least, Jones) a fat fee.

That Jones, before his death in July 1807, had occasionally remonstrated with his noble pupil on academic grounds, not simply because of his absences and animals, is clear from the defensive letter Byron addressed to him early in 1807. ‘I have adopted a distinct line of Reading’, Byron asserted, in the course of explaining why he had declined to avail himself of the formal instruction offered in mathematics, theology and philosophy: ‘this you will probably smile at, & imagine (as you very naturally may) that because I have not pursued my College Studies, I have pursued none.––I have certainly no right to be offended at such a Conjecture, nor indeed am I, that it is erroneous, Time will perhaps discover’.13 Time has not, in fact, revealed any coherent programme of study equivalent to the one Wordsworth (another defector from the Cambridge syllabus) had devised for himself in Modern Languages during his time at St John’s. It seems clear, however, that the Byron who had complained in his first term of residence that ‘nobody here seems to look into an author ancient or modern if they can avoid it’,14 did in fact continue to read avidly, if without system, at Cambridge, as indeed throughout his life. The grounds of his classical education had been laid before he came up to Trinity. Most of the translations from Greek and Latin published in his first volume of poems were products of the Harrow years. History he had always loved. It seems, however, to have been at Cambridge that English literature and, in particular, contemporary poetry, began to engage him seriously. They played, of course, no part in his official studies. Indeed, one of Byron’s chief complaints in ‘Thoughts Suggested’ was the ignorance of English history, law and literature fostered by the University syllabus:

Happy the youth! in Euclid’s axioms tried,

Though little vers’d in any art beside;

Who, scarcely skill’d an English line to pen,

Scans Attic metres with a critic’s ken.

What ! though he knows not how his fathers bled,

When civil discord pil’d the fields with dead;

When Edward bade his conquering bands advance,

Or Henry trampled on the crests of France;

Though, marv’lling at the name of Magna Carta,

Yet, well he recollects the laws of Sparta;

Can tell what edicts sage Lycurgus made,

Whilst Blackstone’s on the shelf, neglected, laid;

Of Grecian dramas vaunts the deathless fame,

Of Avon’s bard, rememb’ring scarce the name.15

During his last term at Trinity, Byron completed ‘above four hundred lines’ of verse anatomizing ‘the poetry of the present Day’.16 ‘British Bards: A Satire’, its initial title, was a youthful polemic which, in lengthening versions, was to go through five editions. Byron came to wish he had never published it at all. Although his faith in Milton, Dryden and Pope as standards of excellence remained fixed, he was later embarrassed by many of the judgements passed on his contemporaries. This poem written in part at Trinity is important, however, because without amounting to the kind of self-dedication Wordsworth had vowed in the summer vacation of his first year at Cambridge, it nonetheless signalled a commitment to poetry, his own and that of other people, about which Byron would often become impatient in the future, even somewhat ashamed, but which was to remain with him for the rest of his life. The Cambridge he knew may have seemed ‘a villainous Chaos of Dice and Drunkenness, nothing but Hazard and Burgundy, Hunting, Mathematics and Newmarket, Riot and Racing’ as he described it in a letter written during that final term.17 Byron’s life there had not been spent in simple acquiescence to its fashionable ‘Monotony of endless variety’.18

The Byron who, several years later,19 was given a spontaneous ovation by the undergraduates, and honoured by the dons when he entered the Senate House to vote in a University election had become, doubtless to the astonishment of most of the members of Trinity’s High Table, a famous man: the author of Childe Harold, The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, Lara and The Corsair. The impact of these romantic poems on the reading public, compounded as it was by the personal magnetism of their author, had been virtually without precedent. Works immediately inspired by the travels in Turkey, Greece and Albania on which Byron embarked after taking his MA, and by his perennial need to find objectifying fictional forms for his own emotional entanglements (which by now included a dangerous liaison with Augusta Leigh, his married half-sister), there was little in their conscious exoticism that seemed to link them to his University days. Yet like Wordsworth, Byron had been influenced to a greater and more permanent extent than he recognised by attitudes and ideas which he encountered in the Cambridge of his time.

On 21 January 1808, a month after his final departure from the University, Byron wrote a letter to Robert Charles Dallas, shortly to become his literary agent, in which he provided ‘a brief compendium of the Sentiments of the wicked George Ld. B’. They included the belief that virtue was ‘a feeling not a principle’, the conviction that human actions were governed by the privileging of pleasure over pain (the last, he joked, borne in upon him after getting the worst of an argument, tellingly conjoined with a fall from his horse), that ‘Truth was the prime attribute of the Deity,’ and death ‘an eternal Sleep’. He also claimed to prefer Confucius to the ten commandments, and Socrates to St Paul, to be sceptical about Holy Communion, and, while disallowing any acknowledgment of the Pope, to favour Catholic emancipation in England.20 As a collection of issues and opinions, it was a distinctively Cambridge blend.

Unlike Oxford at the equivalent moment of time, Byron’s Cambridge had been profoundly marked by the presence and work of Isaac Newton. The legacy of Newton was visible not only in the emphasis on mathematics in the Tripos, but in tendencies towards free-thinking and scepticism which impelled many members of the university into deism and a few others (like Byron’s friend Charles Matthews) into openly confessed atheism. In the realm of moral philosophy, the mechanistic implications of Newton’s thought encouraged a belief in the pleasure principle as the foundation of human action, and in materialist, utilitarian goals. In this climate, the ancient statute debarring anyone who refused to subscribe to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England from taking a degree began to seem oppressive: there was pressure to withdraw it, allowing Unitarians and members of dissenting religions, including Catholics, the same rights as Anglicans. Politically, too, as well as in matters of religion, Cambridge in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century harboured a good deal of radicalism. The effort by Byron’s tutor Jones to subject all undergraduates, regardless of wealth or rank, to the same academic requirements, although defeated at the time, was symptomatic of a democratizing impulse which extended to far wider, non-university issues of political and social reform. Nowhere in Cambridge were these liberal tendencies more pronounced than at Trinity, Newton’s own former college.

At Harrow, Byron’s close friends had almost all been noblemen like himself. At Cambridge they were not. In his final term he became a member of the Cambridge Whig Club and for the rest of his life remained fiercely anti-Tory. Of Byron’s three speeches in Parliament, delivered shortly after he had left Cambridge, one was a plea for Catholic emancipation, another a protest against the use of the death penalty to quell industrial unrest among the Nottingham cloth workers, while the third defended a parliamentary informer. Later on, he was to become deeply involved in the abortive Italian revolution and finally, when social ferment in England disappointingly failed to result in action, to die in the Greek War of Independence. Before then, he had written sixteen Cantos of Don Juan, his unfinished masterpiece, in which the radicalism and scepticism to which he had first been attracted at Cambridge found their mature poetic expression.

Unlike the early Cantos of Childe Harold, Don Juan was not a success with the reading public. Indeed, it came in for increasing moral castigation and abuse, even John Murray, Byron’s publisher for many years, finally declining to handle material so dangerously brilliant.

They accuse me––Me––the present writer of

The present poem of––I know not what,––

A tendency to under-rate and scoff

At human power and virtue and all that;

And this they say in language rather rough.

Good God! I wonder what they would be at!21

Caught in his last years, artistically as well as personally by one of England’s fiercest relapses into puritanism and orthodoxy, Byron nevertheless pressed on, in his Italian exile, with a ‘shocking’ poem that no one (except Shelley) prized. In Ravenna, from a distance of some fourteen years, his time at Cambridge––the days of swimming in ‘Cam’s [...] not [...] very “translucent” wave’, the reading, the conviviality and good talk––suddenly came back to him as ‘the happiest, perhaps, days of my life’.22 John Cam Hobhouse, Byron’s Trinity contemporary, had remained a close if misguidedly loyal friend. After Byron’s death, he nervously burnt the poet’s manuscript Memoirs, in order to safeguard his ‘reputation’. He would have liked to ‘lose’ Don Juan too.

That poem has effectively had to wait until the twentieth century to find its public, to be seen for what Byron, as he went on writing it, gradually realised that it was: in its unorthodox way, a genuinely moral work. Infinitely inventive, both funny and sad, it interweaves Byron’s idiosyncratic version of the Don Juan story with the record of an individual life––his own––lived so expansively and on so many different levels that an entire epoch of European history seems contained within it. Significantly, it is a poem haunted by the figure of Newton, the man whose discoveries had dominated the Cambridge of Byron’s youth. For Blake and for Keats, Newton figured as imagination’s enemy. Wordsworth, although influenced like Byron by Newtonian ideas, put the man himself into his autobiographical poem, The Prelude, only as an afterthought: a memory of the statue in Trinity chapel, with its ‘prism and silent face, / The marble index of a mind forever / Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone’.23 Byron, more complexly, saw Newton as a kind of Janus figure, embodying on the one hand the immeasurable capabilities of the human mind:

When Newton saw an apple fall, he found

In that slight startle from his contemplation––

’Tis said (for I’ll not answer above ground

For any sage’s creed or calculation)––

A mode of proving that the earth turned round

In a most natural whirl called ‘Gravitation,’

And this is the sole mortal who could grapple,

Since Adam, with a fall, or with an apple.

Man fell with apples, and with apples rose,

If this be true, for we must deem the mode

In which Sir Isaac Newton could disclose

Through the then unpaved stars the turnpike road,

A thing to counterbalance human woes;24

But he was also obsessed by Newton’s own wry description, shortly before his death, of himself as merely ‘a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay undiscovered before me’.25

Between these two views of man’s potentialities and achievement, one optimistic, the other despairing, Byron’s epic vacillates and swings. When the narrator writes of his recoil from ‘the abyss of thought’, in favour of ‘a calm and shallow station / Well nigh the shore, where one stoops down and gathers / Some pretty shell’,26 the aged Newton, through some strange act of ventriloquism, authorises Byron’s own characteristic distrust of metaphysical and religious systems. But Byron is also invoking Newton when, immediately after the stanzas about the apple’s fall, he defiantly characterises Don Juan itself––that unsparing investigation of human social, sexual and political relationships––as a voyage into the unknown equivalent to those undertaken by scientists, men ‘who by the dint of glass and vapour / Discover stars and sail in the wind’s eye’.27

After Byron’s death in Greece, at the age of thirty-six, his friend Hobhouse’s request that he be buried in ‘Poet’s Corner’ of Westminster Abbey was firmly refused.28 The Abbey also declined a few years later to accept the life-size statue of Byron by the Danish sculptor Thorvaldsen. Trinity, to whom the piece was finally offered, after it had languished for nine years in the Customs House, proved more courageous. The figure of Byron, seated on a broken Greek column, dominates the long sweep of the Wren Library much as the image of Newton dominates Trinity’s Ante-Chapel (see Fig. 1.1). And the man it represents still arouses passionate reactions of love and hate. Only last year [1987], at a conference in Venice, the former Labour leader Michael Foot came close to assaulting an opponent who maintained that Byron was not, after all, a hero of the socialist movement. T. S. Eliot visited upon the face sculpted by Thorvaldsen an intensely personal dislike: ‘that weakly sensual mouth, that restless triviality of expression, and worst of all that blind look of the self-conscious beauty’.29 Those, on the other hand, for whom Byron’s elusive but compelling personality continues to speak by way of the richest and most brilliant collection of letters in the language, and also in one of its greatest long poems, read that face rather differently. It seems, in any case, wholly appropriate that the author of Don Juan should be commemorated by a statue in the Wren Library rather than in the Abbey. That poem was, in a sense, begun in Cambridge, the place where Byron became confirmed in his adherence to two principles which, as he later said, were the only constant features of his mercurial life and work: the ‘strong love of liberty, and a detestation of cant’.30

Fig. 1.1. The statue of Sir Isaac Newton in the Trinity College Ante-Chapel, by Louis-François Roubiliac (1755).Photograph by Adrian Poole.

Fig. 1.2 The memorial bust of Thomas Jones, Byron’s tutor, inthe Trinity College Ante-Chapel, by Joseph Nollekens (n.d.). Photograph by Joanna Harries, courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

1 Published in The Trinity Review (1988) for the bicentenary of Byron’s birth. Reprinted by permission of the Executors of Anne Barton’s Estate.

2 These lectures, normally annual, were established in 1878 from a bequest of William George Clark; they are typically, though not exclusively, addressed to topics in English literature.

3 Letter to Augusta Byron, 6 November 1805, in Byron’s Letters and Journals, ed. by Leslie A. Marchand, 13 vols (London: John Murray, 1973–94), I, 79. All subsequent references to Byron’s Letters and Journals are to this edition, hereafter BLJ.

4 Robert Robson, ‘Byron’s rooms revisited’, The Trinity Review (Easter 1975), 22–24. Robson supports the probable veracity of J. W. Clark’s statement in Cambridge, Historical and Descriptive Notes (1890), p. 138, about the location of Byron’s room in I1 Nevile’s Court, Trinity College, Cambridge, and the high improbability of the legend, derived from M. F. Wright’s Alma Mater, or Seven Years at the University of Cambridge, by a Trinity-Man (1827), that Byron and his bear were lodged in the south-east corner of the Great Court, K staircase. About the situation of the bear, Robson cites Clark’s statement that it was kept ‘in a stable in the Ram Yard’, noting that ‘it is highly improbable to say the least that the College authorities would then have tolerated a bear in the College’, and even more drily that ‘it is unlikely even now, when discipline is a good deal less stringent than it was’ (22).

5Ravenna Journal, 12 January 1821; BLJ VIII, 22.

6 Letter to John Murray, 18 November 1820; BLJ VII, 232.

7 Letter to Elizabeth Bridget Pigot, 26 October 1807; BLJ I, 135–36.

8English Bards, and Scotch Reviewers: A Satire, 2nd edn (London, 1809). Reprinted inhttps://petercochran.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/english-bards-and-scotch-reviewers1.pdf

9 Letters to John Hanson, 23 November 1805, and Robert Charles Dallas, 21 January 1808; BLJ I, 81, 147.

10Byron: The Complete Poetical Works, ed. by Jerome J. McGann, 7 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980–93), I, 94. All subsequent references to Byron’s poetry are to this edition, hereafter CPW.

11 Peter Cochran, Byron and Hobby-O: Lord Byron’s Relationship with John Cam Hobhouse (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010), p. 313.

12 Letter to John Cam Hobhouse, 26 March 1808; BLJ I, 161.

13 Letter to Rev. Thomas Jones, 14 February 1807; BLJ I, 108.

14 Letter to Hargreaves Hanson, 12 November 1805; BLJ I, 80.

15CPW I, 92–93.

16 Letter to Ben Crosby, 22 December 1807; BLJ I, 141.

17 Letter to Elizabeth Bridget Pigot, 26 October 1807; BLJ I, 135.

18 Letter to Elizabeth Bridget Pigot, 5 July 1807; BLJ I, 125.

19 Late October 1814. Memoir of the Rev. Francis Hodgson, B.D., scholar, poet, and divine: with numerous letters from Lord Byron and others, by his son, James T. Hodgson, 2 vols (London: Macmillan, 1878), I, 292, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb11370276?page=346,347

20 Letter to Robert Charles Dallas, 21 January 1808; BLJ I, 148.

21Don Juan, Canto VII, 3; CPW V, 337

22Ravenna Journal, 12 January 1821; BLJ VIII, 24, 23.

23 William Wordsworth, The Prelude (London: Moxon, 1850), Book III, lines 60–63.

24Don Juan, Canto X, 1, 2; CPW V, 437.

25 Words supposedly uttered by Newton shortly before his death in 1727, reported by Joseph Spence in Anecdotes, Observations and Characters, of Books and Men (1820), I, 158; referred to in Don Juan, Canto VII, 5; CPW V, 338.

26Don Juan, Canto IX, 18; CPW V, 414.

27Don Juan, Canto X, 3; CPW V, 437.

28 [ed.: Geoffrey Bond and Christine Kenyon Jones recall Thomas Babington Macaulay’s observation that ‘we know no spectacle so ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality’, quoted in Dangerous to Show: Byron and His Portraits (London: Unicorn, 2020), p. 81. Unlike Byron, Macaulay does enjoy a memorial statue in Trinity’s Ante-chapel. There is also a memorial bust of Byron’s tutor, Rev. Thomas Jones (see Fig. 1.2), ‘per viginti annos Tutor eximius’ (‘for twenty years an outstanding Tutor’).]

29The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot: The Critical Edition, Volume 5: Tradition and Orthodoxy, 1934–1939, ed. by Iman Javadi and Ronald Schuchard and Jayme Stayer (Baltimore, MA, and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press and Faber & Faber Ltd., 2017), p. 431.

30Conversations of Lord Byron with the Countess of Blessington (London: H. Colburn, 1834), p. 390, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=dul1.ark:/13960/t2795c725&seq=13

2. Pretensions to Permanency

Thorvaldsen’s Bust and Statue of Byron1

Robert Beevers

©2024 Robert Beevers, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0399.02

Fig. 2.1 Bertel Thorvaldsen, George Gordon Byron, original plaster model of the bust of Byron (April–May 1817). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/A257.

The initiative that brought Lord Byron to sit for a portrait bust by the eminent Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen in May 1817 came from John Cam Hobhouse. The impetus to immortalise his friend in stone seems to have been purely personal. Whereas most of those close to Byron, whether as lovers or as friends, were happy to receive as a gift a miniature or even an engraving from a larger portrait, Hobhouse wanted something monumental, and tangible––and he was prepared to pay for it. He was, he liked to believe, Byron’s dearest friend, and certainly he was the most selflessly devoted: ‘a friend often tried and never found wanting’, as Byron himself testified in that warmest of encomiums, the dedication to him of the fourth Canto of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.2Hobhouse may also have been anticipating an eventuality in which he might never see Byron again. When they parted at Dover on 24 April 1816, on his leaving England as a self-imposed exile, Byron had hinted at a premonition that he might never return; Hobhouse noted the inference in his diary and the feeling of foreboding it evoked.3 The choice of Thorvaldsen for the commission may have been influenced by the fee, which would probably have been less than the more celebrated Canova might have charged; but the latter, though still active, was approaching the end of his career and taking few commissions. Thorvaldsen, by contrast, was at the height of his powers; his studio, in which as many as forty men might be seen at work, was one of the sights of Rome to be visited by popes and princes; and his output was prodigious. His personality was no less formidable than his talent: tall and imposing in appearance and sardonic in manner, he was not a man to be overawed by his subjects, however famous and aristocratic. His encounter with Byron––the sittings were no less than that––inspired Thorvaldsen to produce one of his finest busts and the only great portrait of the poet.

Hobhouse’s choice of the most austere of the Neo-Classical sculptors of the day must be seen in the context of his own enthusiasm for classical antiquity. By the time Byron arrived in Rome Hobhouse had spent nearly five months in the city, most of them in close study of the archaeological remains of Imperial Rome and of literary sources, both ancient and modern. His typically painstaking work is now remembered only for his contribution to the Notes, written jointly with Byron, accompanying the fourth Canto of Childe Harold; the book he was to publish in the following year containing material which could not be compressed into the Notes because of its ‘disproportionate bulk’ is now forgotten. Among the literary sources which he and Byron drew upon for the Notes was Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose Geschichhte der Kunst des Alterthums published in 1764 imitated the essentially Romantic interpretation of the surviving artefacts of ancient Greece (or, more typically, Roman copies of lost originals) which came to be known as Neo-Classicism. Byron and Hobhouse read Winckelmann in an Italian translation, which they were to cite in the Notes. Another who almost certainly had read that translation was Thorvaldsen, who, as the brilliant gold-medallist of the Danish Academy, made the pilgrimage to Rome in 1797 where, almost inevitably, he fell under the influence of the prevailing Neo-Classical doctrines. In the words of his French biographer:

The young Dane had hardly taken the first steps in the cause, which was destined to be so illustrious, when he met a fervent disciple of Winckelmann […] Thorvaldsen was strongly encouraged by the learned archaeologist in his enthusiastic admiration for the grand style of antique statuary, and abandoned himself unreservedly to his inclination, thenceforward pursuing resolutely the course which was to lead to the complete development of his genius.

4

The learned archaeologist was Georg Zöega, ‘the Danish Winckelmann’ and doyen of the artistic and literary circle of his fellow-countrymen in Rome. Whilst he recognised Thorvaldsen’s outstanding talent as a sculptor, Zöega found him ‘ignorant of everything outside art’. How is it possible, he complained, ‘to study as he ought, if he does not know a word of Italian or French, if he has no acquaintance with history and mythology […]?’5 The young Bertel became a habitué of the Zöega household, where it seems he set about rapidly learning Italian. He formed a liaison with an Italian maidservant in the Zöegas’ service, by whom he was to have two children. And he adopted the Italian version of his name––Alberto––which he was to use professionally for the rest of his forty-year sojourn in the city.

Thorvaldsen’s Danish biographer, J. M. Thiele, who knew the sculptor personally, believed that he found Byron’s manner at their first meeting distasteful or even repulsive.6Thorvaldsen’s own account, as told to an English visitor to his studio some ten years later, does not suggest antipathy so much as the wryly cynical amusement of a man approaching fifty at the antics of one not yet thirty. Byron ‘appeared the first day in his atelier without any previous notice, wrapped up in his mantle, and with a look which was intended to impress upon the artist a powerful sentiment of his character. It was the first introduction; and Thorvaldsen from whom I heard the fact, admitted that the effect was commensurate with his wishes.’7 But, if Thorvaldsen was not expecting Byron at that particular moment, he was not altogether surprised to see him for Hobhouse had prepared the way in a tactfully worded and even flattering letter. He wrote in the lingua franca of diplomatic and cosmopolitan society, which Thorvaldsen presumably had learned to read after twenty years in the company not just of scholars like Zöega but of his social superiors:

Milord Byron,

dont peut être vous auriez entendu parler comme du premier poète Anglais de nos jours est maintenant a Rôme. Je desire beaucoup qu’il puisse avoir un autre lien sure la postérité, pas moins durable que celui que lui ont fourni ses vers.––Voila pourquoi je le voudrais voir eternise par votre ciseau

.

8

[[trans. by ed.] Lord Byron, whom you have perhaps heard spoken of as the leading English poet of our time, is now in Rome. I very much wish him to have a further hold on posterity, no less enduring than that which his verses have afforded him.––This is why I would like to see him immortalised by your chisel.]

Thorvaldsen’s reply has been lost, so we do not know how many sittings there were or when they took place. The probability is that they were few, perhaps no more than two––an initial sketch in pencil and then the wet clay. He

worked in clay with extreme ardour, until he had set free from it the form which he had imagined, until he had given it the imprint of the thought which he had conceived. When it seemed to him that the clay had adequately rendered his ideas, he executed a plaster from it himself, which he generally finished very carefully: then he gave this to his workmen as a model, and it was their business to translate it in marble […] he constantly superintended the work, frequently retouched it, sometimes finished it himself.

9

Hobhouse was no less impressed by the sculptor’s zest for the job; ‘the artist worked con amore’, he said, ‘and told me it was the finest head he had ever under his hand.’10 According to Thorvaldsen himself, recalling the events as an old man in conversation with his friend Hans Christian Andersen, he asserted his authority from the start:

‘Oh, that was in Rome’, said he, ‘when I was about to make Byron’s statue; he placed himself just opposite to me, and began immediately to assume quite another countenance to what was customary to him. “Will you not sit still?”, said I; “but you must not make these faces”. “It is my expression”, said Byron. “Indeed?”, said I, and then I made him as I wished, and everybody said, when it was finished, that I had hit the likeness. When Byron, however, saw it, he said, “It does not resemble me at all; I look more unhappy.”’ ‘He was, above all things, so desirous of looking extremely unhappy’, added Thorvaldsen, with a comic expression.

11

Much has been made of Byron’s remark, usually to the detriment of Thorvaldsen who, it is said, was of too humble a background and of too simple a nature to ‘comprehend imaginary Misery’.12 Mario Praz, the historian of Romantic modes, suggests a fundamental antipathy between the poet and the artist, not only personally, but as to their aesthetic assumptions. ‘Byron’, he declares, ‘posed as a romantic, but Thorvaldsen carved in the Biedermeyer manner; he was alien to the portrayal of true sorrow: what then could he make of its imitation?’13 There could hardly be a harsher dismissal of Thorvaldsen as an artist: ‘biedermeyer’ was no more than a term of abuse, the mid-nineteenth century equivalent of ‘kitsch’. Those of us who know Byron from his letters to his close friends may suspect him of being facetiously ironical, not a little at his own expense. Thorvaldsen can be forgiven if he did not perceive such a nuance in his sitter’s apparent rejection of his work.

Fig. 2.2 Bertel Thorvaldsen, George Gordon Byron, marble bust of Byron (1824). Thorvaldsens Museum, photograph by Jakob Faurvig, CC0, https://kataloget.thorvaldsensmuseum.dk/en/A256.

But the bust itself reveals that he had recognised in Byron a luminous and resolute spirit to be compared with that of a Greek god. As soon as he saw the plaster model, Byron must have been aware that he had undergone an apotheosis at the hands of the sculptor. He was slightly embarrassed, but at the same time he took a sheepish pride at being thus ‘immortalised in marble while still alive’.14 This sense of unease was revived some four years later, when he heard that a young American visitor had obtained a copy of the bust from Thorvaldsen.

I

would not pay the price of a Thorwaldsen [

sic

] bust for any human head & shoulders […] If asked––

why

then I sate for my own––answer––that it was at the request particular of J. C. Hobhouse Esqre.––and for no one else.––A

picture

is a different matter––every body sits for their picture––but a bust looks like putting up pretensions to permanency––and smacks something of a hankering for

public

fame rather than private remembrance.

15

Byron sometimes affected a kind of philistine indifference towards the fine arts, but his writings reveal that he could be as deeply and powerfully affected by painting and sculpture as by poetry. What he objected to was not art as such but the pretentiousness, as he regarded it, of the attitudes struck by those who professed to appreciate it. Writing from Florence, where he visited two galleries in the course of a visit of no more than a day en route to Rome, he had to admit that ‘there are sculpture and painting––which for the first time gave me an idea of what people mean by their cant […] about those two most artificial of the arts’.16 He was overwhelmed by the visual experience of Rome, its architecture and, perhaps most of all, its sculpture: ‘my first impressions are always strong and confused’, he wrote soon after his arrival in the city, ‘& my Memory selects & reduces them to order––like distance in the landscape.’17 In the fourth Canto of Childe Harold, which he started writing within a month of leaving ‘the city of the soul’, Byron painted Rome in brilliant chiaroscuro: men and gods, past and present seem to emerge suffused with light briefly to be seen before retreating into the shadows. Apollo, in the form of the Belvedere statue in the Vatican, inspired three stanzas which immediately precede the final immolation of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage now hardly distinguishable from the poet himself. ‘The God of life, and poesy, and light–– / […] in his eye / And nostril beautiful disdain,’ though ‘made / By human hands […]’ still ‘breathes the flame with which ’twas wrought’. Harold, by contrast, ‘His wanderings done, his visions ebbing fast / […] His shadow fades away into Destruction’s mass’.18Byron’s apostrophe to Apollo carries echoes from Winckelmann.19 In one of the most famous passages in his GeschichteWinckelmann evokes the spirit of Apollo in the most romantic terms. ‘Apollo’s lofty look, filled with consciousness of power, seems to rise above his victory, and to gaze into infinity. Scorn sits upon his lips, and his nostrils are swelling with suppressed anger, which mounts even to the proud forehead […].’20 And Byron, like Winckelmann, might well have said to himself in the presence of ‘this miracle of art, I feel myself transported to Delos and into the Lycaean groves’.21Byron’s debt to Winckelmann does not, of course, in any way detract from the originality of his verse but his personal identification with the Apollo, at least in some of its features, is clear. Scorn becomes beautiful disdain—a facial expression of Byron’s often commented on by observers, and one which he may have tried to assume in front of Thorvaldsen.

Whether or not Byron saw himself in the image of Apollo, Thorvaldsen certainly did not regard himself as limited to any particular classical model. He aspired towards a classical essence. In this search for an archetype the sculptor would borrow certain features from the antique portraits and combine details from a variety of types which were originally very far removed from each other, in time and space, so as to obtain a result serving his own purpose.22 The Neo-Classical doctrine, in Thorvaldsen’s interpretation, could virtually submerge the individual in the ideal. ‘What you allow in portrait painting’, he declared, ‘is inadmissible in sculpture, because a work of sculpture is a monument, and just as the purpose of a monument cannot consist only in a record of the actual event, thus a statue can achieve this and without reproducing the features.’23 Fortunately for posterity, the sculptor did not adhere to this doctrine in its daunting austerity when faced with Byron. Indeed, his bust revealed the sitter’s features in actuality, even in such a minor detail as his lobeless ears. In short it was a good likeness; Byron himself had to admit, if a little grudgingly, it was ‘reckoned very good’.24When he sought to evoke the spirit of the poet––the ideal––Thorvaldsen did so without resort to extravagant mannerism; the eyes are only slightly uplifted, and their gaze suggests inner reflection rather than a search for inspiration from above. The lightly arched brows unite the separate features as might a frieze across the façade of a classical building. The head rests firmly and easily on a neck of great strength, though it is possible to perceive in the throat that alabaster beauty which was reputed to make women swoon. On first confronting the bust, at least in the original model, Byron’s physical presence almost assaults the viewer. The sculptor recognised what all other portraitists had failed to see, so obsessed were they with the poetical ideal, that Byron was an athlete, a man capable of feats of physical skill and endurance. Only then perhaps does one become aware of a resonance that transcends the purely physical: the strength resides in the whole being, in the spirit made manifest in the flesh. And Byron’s famous affirmation of the immortality of the spirit seems to transpire through the marble: ‘But there is that within me which shall tire / Torture and Time, and breathe when I expire; […]’25

Byron never saw his bust in marble; his favourable judgement was almost certainly based on a report from Hobhouse, who stayed on in Rome for nearly two months before joining his friend in Venice. During that time he called on Thorvaldsen in his studio and in the course of one of these visits he proposed a radical shift of emphasis away from the Greek ideal: he wanted to add a laurel wreath across the brow in the manner of a Roman military conqueror. The sculptor was not averse to this (he used such a motif on his bust of Napoleon), but the idea drew a furious response from Byron.

I protest against & prohibit the ‘

laurels

’—which would be a most awkward assumption and anticipation of that which may never come to pass.—

You

would like them naturally because the verses won’t do without them—but I won’t have my head garnished like a Xmas pie with Holly—or a Cod’s head and Fennel—or whatever the damned weed is they strew round it.—I wonder you should want me to be such a mountebank.

26

So vehement a rejection of the trappings of military honours may seem surprising from one who no more than four years ago had sat for his portrait wearing the dress of a warlike tribesman with a dagger in his belt. But Byron had changed since then and his underlying mood was sombre, barely concealed behind the flippant manner of the rest of his letter. He may, too, have been irritated by the verse which Hobhouse wanted to have inscribed at the base. In the face of such an onslaught Hobhouse could hardly persist; but he did not entirely relinquish the idea. ‘[W]hen the marble comes to England’, he told John Murray later that year, ‘I shall place a golden laurel round it in the ancient style, and if it is thought good enough suffix the following inscription, which may serve at last to tell the name of the portrait and allude to the existence of the artist, which very few lapidary inscriptions do.’27 But the bust took an unconscionable time to reach England and Hobhouse’s clumsy quatrain was never incised. One of Thorvaldsen’s assistants simply chased the name Byronon the front of the herm. Thorvaldsen offered a choice of two modes: the herm, where the head and neck rest on a plain cubic base, or a bust proper where the upper shoulders and chest are revealed in a manner that is Roman rather than Greek. Hobhouse chose the former mode in which Winckelmann’s neo-classical ideal of ‘noble simplicity and serene greatness’28 is perhaps more perfectly realised. But Hobhouse’s frustrated desire to decorate the head of his hero reflects a general drift of taste from the formal and austere towards a naturalism which, at least in Britain, was ultimately to suffuse forms in a layer of glutinous sentiment.

‘Chantrey does not think much of my bust of Lord Byron by Thorwaldsen [sic], nor does he think a great deal of Thorwaldsen’.29Hobhouse was on friendly personal terms with Francis Chantrey, the doyen of English sculptors, and he had a high regard for his opinions on sculpture in particular and art in general. His bust, his masterpiece, as he justly believed it to be, had only recently arrived into his possession, nearly five years on from the heady days with Byron in Rome. Sensitive to a degree to anything which might imply, even indirectly, adverse criticism of his friend, Chantrey’s remarks upset Hobhouse enough for him to record them in his diary. But he may, in his ruffled pride, have misunderstood Chantrey’s words or read more into them than the sculptor had intended. For Chantrey had met Thorvaldsen at the latter’s studio in Rome in October 1819 (he could have seen the Byron bust there) and, according to his Victorian biographer, who knew him far better than did Hobhouse, formed a high opinion of the Dane’s work.30 When, only a year or two later, Hobhouse was faced with the melancholy task of commissioning a statue as a monument to his dead hero it was to Chantrey that he turned.

The idea of a Byron monument to be erected in Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey derived from Hobhouse’s almost obsessive desire for official recognition and public acknowledgement of his friend’s genius. He seemed to want a kind of canonisation as a symbol of secular acceptability. As an attitude to the authority of church and state it hardly accords with his Unitarian upbringing and political radicalism; but Hobhouse was in the process of sloughing off both, and in courting the establishment he invited rebuff. Undeterred by Dean Ireland’s refusal to have Byron buried in the Abbey followed by a brusquely discourteous rejection of an effigy,31Hobhouse bided his time, waiting upon Ireland’s death. He set up a Byron Monument Committee with John Murray as secretary, and solicited public subscription. They circularised members of both Houses of Parliament and appointed corresponding members abroad, but the result was disappointing. By 1829, when the fund was effectively closed, the sum in hand was more than three hundred pounds short of the £2,000 they needed.32 It is not unlikely that Hobhouse consulted Chantrey in arriving at this figure, for he was his first choice for the commission. Again, Hobhouse was rebuffed: Chantrey refused the offer, probably because the fee available was too low. And, as if to add insult to injury, he made a bust of Ireland in the same year. He had already done Wordsworth and was later to immortalise Southey in