Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

'An enthralling thriller ... hypnotically readable' ANDREW TAYLOR 'A compelling tale of a world on the brink of war' THE TIMES 'Ceaselessly entertaining' OBSERVER In the heat of the desert, will the trail go cold? Cairo, 1938 Archie Nevenden is many things: amateur archaeologist; theatre impresario; absent father; potential defector. And now, he's a missing person. His daughter, Prim, hasn't seen him for nearly fifteen years. But she's never given up on him, and now she's on her way to Cairo to assist in the search. Harry Taverner claims to work for the British Council, but Prim knows there's more to it. He clearly has a theory about what happened to Archie, one she's not going to like. As Prim and Harry uncover the layers of Archie's existence in Cairo, they find themselves drawn in to more than one conspiracy. And soon they'll discover that Archie may not be the only one in danger... Praise for S W Perry: 'Powerful, panoramic' Sunday Times 'Beautifully written, entirely convincing' Leonora Nattrass 'Gripping and heartfelt' Elisabeth Gifford 'Sweeping' Daily Mail

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 556

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by S. W. Perry

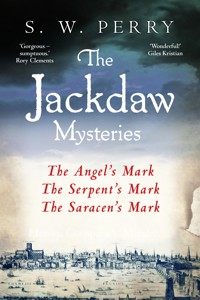

THE JACKDAW SERIES

The Angel’s Mark

The Serpent’s Mark

The Saracen’s Mark

The Heretic’s Mark

The Rebel’s Mark

The Sinner’s Mark

NOVELS

Berlin Duet

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2025 byCorvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Copyright © S. W. Perry, 2025

The moral right of S. W. Perry to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 80546 064 0Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 488 4E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 065 7

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWCIN 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep ComplianceLtd., Ground Floor, 71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin,D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

For Jane

One

Cairo, April 1938

Until the shooting, the only slaughter committed against the Nimrod Theatre had been confined to the review pages of the Cairo newspapers. A cosy but unimposing little auditorium off Kamil Street, The Nim, as its habitués preferred to call it, was known more for the brio of its productions than for their commercial success. Before that warm and otherwise agreeable Cairene night, an audience could rest safe in the knowledge that a pistol was nothing more lethal than a prop, that the shot that made them jump in their seats was merely a blank, the resulting blood comfortingly fake. But – as all theatre folk know only too well – even the best runs must come to an end some day.

The time of the attack, 10.27 p.m., was not in doubt, it being the solemn habit of the manager – an over-earnest young Egyptian named Moussa Bannoudi – to set the foyer clock in accordance with the start of Radio Cairo’s early-evening news broadcast. That night it took a fatal ricochet, stopping the hands dead and thus precluding any debate.

Outside, beyond The Nim’s Moorish archways, painted a lustrous red and gold in a European’s imagining of a caliph’s treasury, the city was taking its pleasures as it did on any other night. In the adjacent Ezbekia Gardens, a slice of belle-époque Paris transported to Egypt, the street lamps threw their warm light into the groves of banyan and acacia trees. Friends and lovers strolled along the pathways, around the lake and over the little wrought-iron footbridge. At nearby Santi’s a cosmopolitan mix of Egyptians, Lebanese, British and French queued noisily for a late table. In the Long Bar at Shepheard’s Hotel, and on the floating nightclubs moored along the Nile, the lounge-lizards were hard at work. At the Kit-Kat Club, officers from the British garrison vied with smooth young men from King Farouk’s court for the attention of the chorus girls. And at the Nimrod Theatre that evening’s performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – already dismissed by the theatre critic of Al-Misri as ‘lacklustre’ – had just drawn to a close. Behind the safety curtain, the cast were rushing to cleanse themselves of greasepaint and sweat. In the auditorium the house-lights were up and the audience was already pushing for the exits.

Awaiting them in the lane outside was a small squadron of taxis, from which issued a growing hysteria of waving arms and blaring motor horns, the usual Cairo method of attracting trade. The more romantically inclined could choose instead a hantour, a horse-drawn carriage – there were several for hire that night – whose drivers, clad in traditional galabeyas, sat cradling their long whips like fishermen at their rods. And while the Cairo police later took copious statements from them all, it was perhaps inevitable that their attention was focused more on those coming out of the theatre’s lobby rather than on the four men who entered it.

They came from the direction of Ibrahim Pasha Square, or so the driver of the hantour nearest the entrance said later to a white-jacketed Cairo police constable while his horse munched from its nosebag. And there were three of them, not four. Not so, claimed a motor-cab driver. They came from across the Gardens, and they were five in number. They were European gangsters… they were Egyptian nationalists… they were Jews… they were the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and they came by tram…

While the shaken witnesses inside the foyer each had their own recollection and guarded it jealously, all agreed there had been no warning given. ‘It wasn’t as if they came in brandishing tommy guns like mobsters from Chicago,’ said the redoubtable Madame Nasoul, who ran the front-of-house. And indeed had she been smoking one of her foul Kyriazi Frères, it is quite possible that in the resulting smokescreen no one could have described the assassins in any consistent detail at all.

‘I thought they were waiting for someone,’ Madame Nasoul told the fiercely moustachioed detective inspector who took her statement – they being four gentlemen in overcoats and fedoras. ‘They came in over there,’ she said, pointing at the left-hand brass-edged swing door that led to the street, ‘maybe two minutes before the inner doors opened.’ And then, turning, with an imperious sweep of her hand she gave the inspector a rapid visual tour of the foyer. Look up to the gallery, please, Inspector. Observe the ottoman couches, thoughtfully provided for those who need to sit while chatting during the interval, and where we laid out some of the wounded. Follow the curving red-carpeted stairs – admittedly a little worn, but do you know what carpet costs these days? – down to the ground floor and the box office – note the interesting arabesque lattice-front dating from the Khedive era – and finally to the stalls: one double door on each side, hidden away beneath the circle’s overhang like the private booths in one of the naughtier clubs on Emad al-Din Street. And, all the while, studiously ignoring the sticky pools of drying blood.

When the swing door first opened and the four men entered, Madam Nasoul had asked herself why anyone would wear an overcoat on such a warm night. But if her suspicions were aroused, it was only because she feared they might be gentlemen from the bank, come to serve a foreclosure notice, which – given the precarious nature of the Nimrod’s financial health – was a constant possibility.

At first they did nothing very much at all. Adopting a nonchalance that, with hindsight, Madame Nasoul agreed should have provided a warning, they made a casual pretence of studying the various photographs on the lobby wall: portraits of some of those who had appeared at the Nimrod since its opening late in the previous century, when it had been known as the Karnak. Some of these faces were Egyptian, including Rose al-Youssef and Zaki Rostom, while the others belonged mostly to second-tier English repertory actors seeking relief and employment after the mildewed trials of end-of-the-pier stages and provincial boarding houses. If the four men found anything to excite them in this collection, they did not reveal it. Indeed, on later reflection Madam Nasoul thought they might have been using the glass to ensure their fedoras were pulled well down over their brows. She considered asking them if she might be of assistance. But by that time the departing audience was already streaming out of the auditorium. This diversion drew her away and may very well have saved her life.

It was over almost before anyone realized what was happening – a sudden fusillade of shots. Maybe ten. Some said more. Some said fewer. Those whom the bullets struck were mostly not in any position to count.

From the cab rank it sounded like little more than the backfiring of a motorcycle engine. But inside the confined space of the Nimrod’s foyer, it had the deafening brutality of an artillery barrage.

It stopped almost as abruptly as it began. For a moment there was silence, the stunned quiet of incomprehension broken only by the wet slither of blood-soaked clothing on stone as people sought to crawl away from the danger, or from their own pain. Someone moaned, a deep groan of anguish rising from the depths of damaged flesh. Then the screaming started.

The swing doors all but flew off their ornate brass hinges as terrified people fled out into the street, causing the usually placid hantour horses to startle. Once freed from the theatre’s interior, panic turned truth into wild speculation, and the four gunmen into twenty. In a dozen breathless exchanges it was declared, with absolute certainty, that the assassins were still inside, stalking at will through the auditorium; that they had accomplices in the street ready to take potshots; that they were on the roof or rampaging through the nearby Hotel Bristol; that at this very moment they were gunning down people at the Alhambra Music Hall.

In fact they had calmly disappeared into the Ezbekia Gardens before the cordite smoke dissipated, leaving their discarded overcoats and fedoras in a neat pile beneath a bush by the lake, there to be discovered at daybreak by the police.

Moussa Bannoudi and Madame Nasoul tended to the injured as best they could, joined by the braver members of the cast and the backstage crew courageous enough not to lock themselves into cupboards or the dressing rooms. By the time the first police officer arrived, the polished tiles of the lobby were a kaleidoscopic picture of bloody footprints. The constable, a gangly Sudanese boy of barely twenty in a white tunic and fez, took one look at the carnage and began blowing his whistle. He went on doing so until Madame Nasoul told him brusquely to take the wretched instrument outside because the noise wasn’t helping anyone.

The death toll was less than the number of prostrate bodies might at first have suggested: six fatalities and eight wounded. Amongst them was an assistant master from the English School at Heliopolis. The English-language newspapers, while giving him a glowing obituary, referred to the Egyptian casualties – amongst whom were a doctor from the Kasr al-Ainy hospital and his wife – only as locals.

The attack was naturally the subject of much speculation and many column inches in the next day’s newspapers and over the days that followed. The Egyptian Gazette, being Englishowned, stated confidently that it was a terrorist outrage, staged by nationalists for whom the implementation of an Anglo-Egyptian treaty – committing Britain to eventually removing all her troops from the country – was progressing too slowly by half. The leader writer of Al-Misri suggested the assassins might have been supporters of Benito Mussolini, and the attack staged in revenge for British criticism of Italian atrocities in Abyssinia. A suggestion in the periodical Raghaeb that the shooting was a protest at Western debauchery held little water, if any. For the zealot with murderous intent there were far more inviting targets elsewhere in the city.

Despite the encouragement of Thomas Russell, the English commandant of the Cairo city police, known throughout Egypt as Russell Pasha, none of the detectives investigating the crime could establish any connection between the victims, other than that they had chosen to watch the play. Until, that is, it was noticed that one of them – the unfortunate assistant master from the English School – bore a passing resemblance to the owner of the Nimrod Theatre, one Archibald Nevendon.

Nevendon was already known to the police, but not because of any former criminality. He was an upstanding member of Cairo society, director of the Egyptian office of the Anglo-Levantine Oil Company. And he was the man who, singlehandedly, had been keeping the Nimrod Theatre afloat since purchasing it as a barely going concern several years previously. Indeed, his photograph was amongst those on display in the lobby. It hung beside that of his late brother Nimrod, after whom the theatre was named.

And there, for the time being, the trail went cold. Because, on further investigation, it was swiftly determined that Archie Nevendon had not been seen at his office for several days. Nor had his usual haunts had so much as a sniff of him. He had apparently vanished off the face of the Earth like desert mist at sunrise.

Two

The black Humber saloon pulled off the lane and began to edge cautiously between the ivy-covered stone pillars that guarded the entrance to Bevern Lodge, a minor and gently mouldering estate in the folds of the Ashdown Forest, midway between the southern fringes of London and England’s south coast. Watched by the young woman in tweeds and headscarf who, until a moment ago, had been standing in the shadow of an ancient beech tree beside the curving driveway, it came to a halt on the gravel barely ten yards away from her.

Driver: male, she noted. Single passenger beside him. Also male. Both middle-aged. Pencil moustaches lending a touch of severity to their otherwise forgettable faces. Creased lapels suggesting cheap off-the-peg suits. Eyes taking in far more than they were giving away.

Until she’d heard the engine, Primrose Nevendon had been topping up the ancient metal bird-feeder that her father had strung on a cord from the lowest bough when she’d been too small to reach it without being hoisted onto his shoulders. It was mid-April, and beyond the thick laurel hedge the forest was once again turning itself into a mix of Birnam Wood and grouse moor, somehow dropped by mistake into the downs of East Sussex. Fallow deer grazed amongst the stands of Scots pine. On the sandy paths, adders basked in the spring sunshine. And beside Bevern’s driveway, a perceptive young woman reached a conclusion: policemen – in anyone’s language.

Prim lowered her arm, letting the paper bag of birdseed rest against her right knee, and waited in silent expectation while the car window wound down with the juddering squeak of rubber against glass.

‘Bevern Lodge?’ asked the car’s passenger.

Primrose set down the bag of birdseed and came closer, stooping a little to bring her face nearer to his. ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Is this Bevern Lodge, luv? Only there’s no sign anywhere.’

Pulling the scarf knot away from her chin, Primrose gave a regretful smile. ‘Sorry – luv. We had to take it down.’

‘Something to hide, eh?’ suggested the passenger almost flirtatiously, for by now he could see that this was not the sturdy and weathered countrywoman he’d anticipated. ‘Being a bit naughty, are we?’

‘People from the village kept throwing paint over it.’

The driver rested his hands on the steering wheel and spoke across his companion. ‘From what we’ve heard about you lot, can’t say I’m surprised.’

Primrose shrugged. ‘If you’ve come here just to insult us, we can get that down at the Rose and Crown, thank you very much.’

The man in the passenger seat had a pencil sticking crookedly out of his breast pocket and the drooping eyes of someone who holds suspicion amongst the highest of human virtues. He rested one elbow on the window frame and let his head loll out as if he had no muscles in his neck. ‘Now we’ve established we’re in the right place,’ he said, in a tone that suggested the missing sign and the young woman were co-conspirators in a crime as yet unnamed, ‘are you Celestina Lombardi?’

‘No. You want my mother,’ Primrose said. ‘I’m the daughter, Primrose – Prim to my friends. But I take it you’re not here to be friendly.’

‘And what precisely makes you think that, Miss Lombardi?’

‘Oh, just a hunch,’ she replied. ‘And it’s Nevendon, by the way – Prim Nevendon. I kept my father’s name when they divorced.’

‘Don’t suppose you’ve seen him at all, recently?’

‘Only if you consider 1924 recent,’ Prim said, looking surprised. ‘Why do you want to know?’

‘I’m Detective Inspector Swinnell,’ the man in the passenger seat said, answering a different question entirely. He glanced back into the motorcar. ‘And this is Detective Sergeant Mullen.’

Mullen leaned forward to peer through the windscreen. ‘Nice little place you’ve got here. Must have cost a bomb. Foreign money, was it?’

Prim Nevendon smiled sweetly. ‘This can’t be about my overdue library book; they’d have sent a superintendent at the very least.’

Swinnell didn’t rise to her bait. ‘Assuming that you’ve seen your mother since 1924, perhaps you could tell us where we might find her.’

‘Up at the house,’ Prim said. She pointed up the drive. ‘Keep going and round the bend. You can’t miss it.’

‘What do we do when we get there?’ enquired Mullen sarcastically. ‘Ask the butler?’

‘If we had a butler,’ said Prim evenly, ‘I wouldn’t be standing here wasting my time talking to Dick Tracy and his sidekick, now would I?’ She stepped back from the car. ‘You’re bound to bump into some of the Fraternity up there. They’ll be able to help you. My guess is you’ll find her in her pottery studio.’

‘Her pottery studio,’ said Swinnell archly, turning to his companion. ‘Do you have a pottery studio in your semi in Dulwich by any chance, Sergeant Mullen?’

‘Next to the indoor swimming pool, sir.’

Swinnell began to wind the window up, his shoulder revolving as he turned the handle, as if he was exercising an ache. He stopped halfway. ‘You might want to follow us,’ he suggested to Prim. ‘After we’ve spoken to your mother, I dare say we’ll be wanting a word or two with you, Miss Nevendon. Not planning to leave the country or anything of that nature, are we?’

Prim frowned. ‘Why on earth would I want to do that?’

‘Oh, it was just a thought. Rome… Berlin… somewhere of that nature.’

‘I’m perfectly happy in East Sussex, thank you all the same, Detective Inspector,’ Prim replied, but by then she was talking to the glass.

She heard Mullen put the Humber into gear. Could have offered me a lift, she thought as it disappeared amongst the trees. Perhaps the discourtesy was a punishment; they were policemen, after all. Maybe they’d guessed she was lying to them. Not about Archie, of course. But about being happy in East Sussex.

The Lodge was a rambling Tudor manor house built by a Sussex wool-merchant-turned-sea-wolf who’d made his fortune pirating New World silver from the Spanish. In the intervening centuries it had sagged into the landscape like a sandcastle in a slowly encroaching tide. It boasted a tithe barn, several priest-holes and a moat, now given over to daffodils and meadow flowers. Celestina Lombardi had inherited it from an English aunt, otherwise it might have been sold in the divorce. Now, under her often-dreamy and scatterbrained rule, it was home to a small, eclectic community of artists and third-tier philosophers, known amongst themselves as the Bevern Fraternity, and to the surrounding hamlets as ‘that bunch of Eyeties up at the big house’.

Besides Celestina – who, as Prim had explained to the detective inspector, was mostly to be found in her potter’s smock with her greying hair tucked into a poacher’s hat – there were in fact only two members of direct Italian descent: Gianni, a shy young fellow whose slender hands were permanently stained by the ink from his efforts at screen-printing, and Mariana, who wrote poetry in the style of Boccaccio and affected the tragic air of a modern-day Ophelia, even when she was happy. The latest addition to the Fraternity was a German, Gertrude Bernbaum, a young artist who’d fled to England because the Nazis had pronounced her work degenerate and who was permanently worried sick for her parents, who couldn’t get the right papers to leave Stuttgart. The rest were English to their roots – except for Angus. Angus was a would-be playwright. He’d never had anything performed in public, but he was always pestering Prim to do the set design for his next great project that was sure to wow. A friend of a friend of John Gielgud was even now championing his efforts – and had been for several months. He was sure to hear something soon.

And playing the role of big sister to them all, sometimes even to her mother, was Primrose. Or Prim to her friends, if they weren’t police detectives. Prim Nevendon, twenty-four, daughter of Celestina and Archie, occupation – of sorts – freelance stage designer, with a few provincial successes to her name but nothing yet to hang a hat on, let alone a reputation. Almost, if not quite, single out of choice, because quite frankly the sort of boys one met these days – well, so far, they’d proved about as appealing as a wet weekend in Bognor. And, if she were being honest with herself, scared stiff for the future: hers and everybody else’s. And who wouldn’t be these days, what with that dreadful Mr Hitler in Germany ranting away like a lunatic?

Reaching the house, Prim saw the now-empty Humber parked outside. Its nearside front tyre was plonked just enough onto the verge to flatten some of the daffs she’d planted last year. Deliberate and wanton violence, she decided. Police brutality. Next thing we know, we’ll be exactly like Germany, if we’re not careful.

‘These two gentlemen are police officers, darling.’

Celestina was sitting at her old potter’s wheel, still wearing her poacher’s hat, with her arms, her apron and the floor around splattered with a milky residue of liquid clay. Swinnell and Mullen stood with their backs to the single window, looking as though they’d stumbled upon a crime scene in which extreme violence had been committed with a sack full of flour and a hosepipe.

‘I know,’ Prim said. ‘I met them on the drive.’

‘They claim they’re from the station in East Grinstead,’ her mother said. ‘I don’t believe that for a moment. We know almost every policeman in the county by sight, don’t we, Primmy? God knows, we’ve had them sitting in their motorcars out there in the lane long enough, taking note of who comes and who goes. Scribbling away in their notebooks. Probably got binoculars, too. What do you think we’re going to do, Inspector Swinnell – raise a giant statue of Signor Mussolini on the lawn? Signal from the dovecote to submarines full of Nazi spies off Seaford?’

Swinnell could have been wearing a bulletproof vest beneath his jacket for all the damage her sarcasm did him. ‘It’s a matter of allegiances, Mrs Nev—’ he paused, before correcting himself. ‘Mrs Lombardi.’

‘Allegiances? Don’t be so bloody impertinent, Inspector. I’m a British citizen. I was born here.’

‘What is all this about, please?’ Prim asked.

Without waiting for Swinnell to speak, Celestina said, ‘They’re here because your father’s gone missing again.’

The tone in her mother’s voice was the one she always used when speaking of Archie: disinterest as a disguise for complete loathing. It always brought out the combative side of Prim’s nature. Where her parents were concerned, she didn’t believe in absolutes.

‘You don’t sound overly concerned, Mrs Lombardi,’ said Mullen.

‘Why would I be concerned? It’s not as if he hasn’t done it before.’

‘I see,’ Mullen replied, raising an eyebrow. He drew a notebook from his coat pocket and thumbed it open. ‘Would you care to tell us about the previous occasions on which he has disappeared?’

‘There was just the one.’

‘And when would that have been?’

‘February 1924. He walked out and never came back. Did us all a favour, to be honest.’

‘What do you mean, missing?’ Prim asked. ‘Is he all right?’

Swinnell turned in her direction. ‘All we know is that Mr Nevendon hasn’t been seen either at his office or at his customary haunts for some time. I can’t be more specific than that.’

‘Have they checked the local cocaine dens, or the whorehouses?’ Celestina enquired.

Swinnell’s brows lifted. ‘Should they have?’

‘My ex-husband had the scruples of an alley cat, Detective. Only alley cats tend to be more reliable.’

‘Mummy!’

Celestina opened her palms defensively. A trickle of watery clay ran down her right forearm and dripped onto her knee. ‘It’s the truth. That’s what we’re supposed to tell policemen, isn’t it? Otherwise they might get out their rubber truncheons.’

‘You’re thinking of the Gestapo, madam,’ Mullen said. ‘We’re from the East Sussex Constabulary.’

‘There’s a difference?’ said Celestina archly.

Inspector Swinnell emitted a slow, official cough. ‘We had been led to understand that Mr Nevendon was an upstanding member of the British community in Cairo. Are you suggesting he might have a secret life?’

Celestina’s reply was laced with bitterness. ‘Casanova was an author – but he’s not exactly famous for his books, is he?’

Mullen’s mouth suffered a brief spasm that was very nearly a smile. He turned to Prim. ‘And what about you, Miss Nevendon? Do you remain in contact with your father?’

‘Egypt isn’t exactly on the doorstep, is it, Sergeant?’

‘I’ll take that as a “no” then.’

Prim felt her cheeks burn. How could she have been so transparent? And to a policeman at that. In what she had imagined was a pithy grown-up reply, she had exposed the quiet childhood ache she felt at the infrequency of Archie’s correspondence. ‘That’s not at all what I meant,’ she said, too quickly and far too defensively for her own liking. ‘He sends me a card at Christmas, and on my birthday. He writes letters every now and then. We keep in touch.’

‘Regularly?’ asked Mullen.

‘Not as much as I should like. At least not these days. He has a very important job. I imagine it makes heavy demands upon his time.’

‘And in these cards and letters, has he ever indicated any fears he might have for his safety? No hint of why he might have taken it into his head to disappear?’

‘Of course not.’

‘Why “of course”?’

‘Because if he had, I would have asked him how I might be of help,’ Prim said, barely avoiding an accusing glance at Celestina.

‘What about this theatre business he’s involved in?’ Swinnell asked.

‘You mean the Nimrod?’

‘Has he ever mentioned any troubles he might be experiencing on that front?’

‘What do you mean by “troubles”, Inspector?’

‘Like impending bankruptcy.’

‘The theatre is a tough business to make money in, Inspector,’ said Prim. ‘I don’t suppose it’s any different in Cairo.’

Mullen was writing in his notebook. Without looking up, he asked, ‘What exactly is his connection with this theatre, Miss Nevendon? Is he one of your amateur dramaticals, by any chance? I only ask because the missus is very much into that sort of thing.’

‘He owns it,’ Prim said bluntly.

‘Well, well. An impresario,’ said Swinnell mockingly.

‘Not really. It’s another of his hobbies. Well, more than a hobby really.’

‘More in what way?’ asked Mullen.

Prim glanced at her mother, but Celestina seemed content to let her do the talking. ‘Well, you see, it’s named after his younger brother, my uncle Nimrod,’ Prim said. ‘My father purchased it after the Great War. They had both served on the staff of General Allenby during the campaign in the Middle East. They’d discovered the theatre when they were on leave.’

‘Isn’t it a bit unusual, purchasing a theatre – and in Cairo, of all places?’ suggested Swinnell, as if Prim had been pitching a doubtful alibi.

‘They do have theatres in other countries, Inspector,’ she said. ‘And Uncle Nim had an early ambition to run one. Granny G always said they were like a couple of young boys with a secret den to play make-believe in. Isn’t that true, Mummy?’

Celestina shrugged. ‘Grace may have said something like that.’

‘Anyway, they found this rundown old place and decided to give it a new lease of life,’ Prim went on. ‘Saw themselves as a pair of regular D’Oyly Cartes, according to my grandmother.’

‘May we have the address of this uncle, Mr Nimrod Nevendon?’ Mullen asked.

‘Certainly,’ said Prim. ‘Try the War Cemetery in Jerusalem. I can’t tell you what plot.’

‘Ah,’ said Mullen with a wince. ‘I see. Please forgive me, Miss Nevendon.’

‘That’s all right, Sergeant. You weren’t to know. He died in late 1917, fighting in Palestine against the Turks. My father was heartbroken. He vowed to keep that theatre going in Nim’s memory.’

Swinnell wrote briefly in his notebook, then placed the end of his pencil against his thin moustache and gave a little rub, as if it suddenly offended him and he wished to erase it. Or perhaps he was simply preparing himself for what he said next. ‘I’m sorry to have to tell you, but there was shooting at the theatre a few days ago.’

Prim’s hands flew to her mouth. ‘Dear God, not Archie—’

‘No, not your father,’ Swinnell replied hurriedly. ‘The attack happened after he’d gone missing. But the local police do believe it might have something to do with his disappearance.’

‘A shooting – that’s just awful,’ Prim said, looking at Celestina, who simply shook her head as if to say: I could have told you things would come to this, one day.

‘There were several fatalities,’ said Swinnell in a matter-of-fact way. ‘But your father was not amongst them.’

‘Why would anyone do something like that?’ Prim asked, appalled. ‘That sort of thing only happens in Chicago.’

‘Forgive me, Miss Nevendon,’ Swinnell went on, ‘but did your father ever speak of politics in his letters, by any chance? I’m thinking international politics. The present tensions in Europe, for instance.’

Celestina had suddenly found her voice again. ‘If you mean Nazi Germany and Herr Hitler, Inspector, or Signor Mussolini in Italy, why don’t you come out and say so? We’ve heard it all before.’

Swinnell turned towards her, almost as if he’d forgotten she was there. ‘Mr Nevendon is – let us use the word is until we have cause to think otherwise – a senior director of Anglo-Levantine Oil. Is that not true?’

‘Yes. He runs their Cairo office,’ said Celestina. ‘What of it?’

‘Then I suspect your former husband must have access to all sorts of confidential information that would be of interest to a potential enemy in the event of war breaking out,’ Swinnell went on. It sounded like a recitation, as though he was speaking someone else’s lines. ‘Take the new oil pipeline from the fields in Iraq to the terminal at Haifa in Palestine, for example. It was installed to supply the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet. Then there’s the strategic importance of the Suez Canal. I dare say Mr Nevendon would have inside knowledge of that, too.’

‘My, they do teach you a lot in the police, don’t they?’ Celestina said archly. ‘I didn’t know the training was so encyclopaedic.’

Swinnell chewed her response and found it tasted unpleasant. ‘I’m sure Mr Hitler would be only too happy to get his hands on information pertaining to such matters,’ he said loftily.

Prim said, ‘Are you suggesting Herr Hitler has kidnapped my father, Inspector? Isn’t that a little far-fetched?’

‘Certain people in authority are at this very moment considering the possibility,’ Swinnell responded cryptically.

Prim gave him a teasing smile. ‘I think you’ve been reading too much John Buchan in your lunch break at the police station.’

‘There is another possibility of course,’ Mullen piped up from the wings. ‘Perhaps he’s decided to go over of his own free will.’

‘Go over? You mean defect – to the Nazis?’ Prim said. ‘That’s preposterous. Archie would never do such a thing.’

‘Who cares where he’s gone?’ Celestina murmured to herself. Then, to Swinnell, she added, ‘If you find a body, I suggest interviewing the vultures. Ask them if they found a backbone on the carcass.’

‘Mummy! That’s horribly uncharitable,’ Prim scolded. Facing Swinnell, she said, ‘My parents had a bad divorce. She doesn’t mean it.’

Celestina stood up and wiped her arms on her smock. ‘I really would like to get back to work, if that’s not obstructing you in your duties, or whatever you call it.’

Swinnell’s manner hardened. ‘One more thing, Mrs Lombardi. What exactly do you get up to here at Bevern Lodge, if I might be so bold as to ask?’

‘What do you mean by “get up to”?’ Celestina hissed, flapping her stained smock and reminding Prim of an angry goose. ‘I think it’s time you left, Detective Inspector,’ she said. ‘But for the record, neither I nor my daughter, nor anyone else here at the Fraternity is, or has ever been, an agent of a hostile power – whatever you or the ignorant bigots who throw paint over the entrance pillars like to claim. We’re artists, that’s all. We have no political affiliation to foreign governments, and we just want to be left in peace. There, you can write that down in your silly notebook.’ She became tearful, although when Prim rushed to comfort her, she flapped a hand to wave her off. ‘It’s unbearable, all this innuendo. It’s prejudice, that’s what it is. Prejudice, pure and simple.’

Prim said sternly, ‘I think my mother has made her point clearly enough, don’t you? Good day, gentlemen. When you leave, please try not to destroy any more daffodils.’

Swinnell tucked his notebook and pencil inside his jacket, his face impassive. ‘If you should happen to hear from your father, Miss Nevendon,’ he said smoothly, ‘perhaps you’d be good enough to telephone the police station at East Grinstead and ask for me by name. Can you do that for me?’

Prim agreed that she could. She escorted the two men to the hall and closed the door behind them. She thought of bolting it, but knew they’d hear the clank of the ancient lock and think her actions suspicious. So she went to the kitchen to put the kettle on.

When she returned to the studio, bearing a tea tray, her mother was at her potter’s wheel, hunched over it like a murderer, gripping the spinning clay as if she intended to strangle it. Prim watched her for a while in silence. She was a fine artist when the temper wasn’t on her. She’d once aspired to be another Clarice Cliff, selling her brightly coloured wares to the best people in London stores. Somehow it had never quite become a reality. Now Celestina sold mostly to her friends, her only commercial outlet being a shop in the Brighton Lanes run by an ageing tenor and his young male friend – something else Prim suspected her mother blamed Archie for.

Clearing a space amidst the jumble of knives, coils of cutting wire, scrapers and coilers on a nearby table, Prim set down the tray. ‘Surely you must be a little worried about him,’ she ventured tentatively, pouring the tea the way Celestina liked: milk first and to hell with snobbery.

‘They weren’t from East Grinstead,’ her mother replied without looking up. ‘They were Special Branch. You could tell by the size of their feet. Why do they have to come here asking their impudent questions as if we were enemy agents?’

‘I think they just want to know what’s happened to Archie,’ Prim said, taking a sip of tea. ‘And to be honest, so do I. It might be something awful. He might be hurt, or – God forbid – worse.’

Celestina took her foot off the pedal and the wheel slowed to a halt. The clay gleamed wetly as though it had risen from the ocean, its gaping mouth desperate for air. She looked up at her daughter. ‘You were only ten when he left, darling. You were too young to know about things. Your father is like bad clay. Too many impurities. Too many voids. Nothing good will ever be made of it.’

‘That’s not how I remember him,’ Prim said, trying hard not to sound argumentative.

‘Yes, well, that’s you all over, Primmy. Too good to see the bad in people. Wait till you get hurt, then tell me if you still feel the same.’ Celestina reached across to the tray and drank noisily from her teacup, something she had started doing years ago simply to annoy Archie’s mother, Lady Grace Nevendon. Then she put her foot back on the pedal and her head went down again. The potter’s wheel began to whir once more.

There was no point in pushing further, not when Celestina was in one of her emotional deep-freezes. So Prim left her mother to it and went outside to inspect the damage the Humber had done to the daffodils. Kneeling on the grass verge, she imagined herself eight years old again, trowel in hand, digging up the little clay effigies that Celestina had made specially for Archie to bury around the grounds, so that Prim could play the great archaeologist. It was the year Howard Carter had found King Tut – 1922. Two years before catastrophe came into her life in the form of her parents’ divorce. She tried to imagine Archie beside her now, not as she had seen him last – a bald, stocky man with the weary look of a prizefighter on the downside of his career – but then. Young and vigorous. Wearing his flannel Oxford bags and cricket jumper, smelling of Bay Rum cologne and linseed oil. Telling her stories of how he and Uncle Nim had played the amateur archaeologists in the years before the Great War, brown-kneed in their cavernous shorts in some dusty Mesopotamian defile while they dug for the lost treasure of Gilgamesh and came home with nothing to show for it but blisters. A young father with dreams.

Lady Grace Nevendon – Granny G to the family – had long ago told Prim how, as a child, Nimrod had dreamed of opening a grand theatre in the West End, while Archie was going to run the Middle Eastern galleries of the British Museum. Neither ambition had been fulfilled. Like so many of their generation, the Great War had got in the way. Nim had died of gangrene in a Jerusalem hospital, courtesy of a fragment from a Turkish hand-grenade, while Archie had come home consumed with guilt for having failed to protect his little brother. Maybe that had been what had destroyed his marriage to Celestina – even as a child, Prim had suspected that. After a few years of itinerant prospecting in Africa and the East, Archie had ended up behind a desk at the Anglo-Levantine Oil Company in Cairo. What was the point of dreams, wondered Prim as she nipped off the daffs that had succumbed to the Humber’s tyres, when even the brightest ones can be crushed by someone else’s careless parking?

Larchford Farm lay a short way down the lane from Bevern Lodge. The farmer, John Hanslope, was barely fifty, but looked more like eighty. Gaunt and grey-faced, he wheezed almost as much as the ancient steam tractor he employed on his land. He had been gassed in the Great War. Now his son ran the business. Knowing to his cost where jingoism could lead, Mr Hanslope Senior had had his fill of it, which was probably why he was one of the few people in the Forest with any time for the members of the Bevern Fraternity. Before the divorce, he’d been a firm friend of Archie’s. By the time Prim turned five, she could count every horse in the Larchford stables as a close friend, bursting into tears when Celestina told her she couldn’t keep them in her bedroom. Now, when she wasn’t in London, she would often ride out in the Forest on Mr Hanslope’s spirited chestnut hunter, to clear her mind and put things in perspective. An hour after the two detectives had left, she was saddling up.

Riding alone along the skyline, with the heather readying to bloom on the slopes that rolled away towards the South Downs, she had already half-decided to go to Egypt. After all, what was there for her in either London or Bevern?

A relationship with a much older theatre director was coming to its natural end, with all the emotional jolting and teeth-jarring of a minor motorcar accident, leaving her with a choice: either roll on until the wheels fell off, or head straight for the nearest tree and be done with it.

Harold Armitage, twenty years her senior, had only ever been a fling, but a fling that had got a little complicated. It was like a Béarnaise sauce: great when it worked, only occasionally worth the effort. It was the one affair she’d kept hidden from her mother, because Prim was almost certain she’d be accused of seeking a surrogate for her missing father’s love. On occasions, Celestina could be uncomfortably direct.

Riding through the pines at King’s Standing, she saw a troop of Territorials resting after a run. They called to her with good-natured juvenility until their sergeant told them to button their lips. She waved at them and went on her way, down a sandy track, giving a wide birth to the adders coiled sleeping on the warming earth in the spring sunshine.

If the newspapers – and Mr Hanslope – were right, there could soon be another European war. She’d seen too many women of Celestina’s generation condemned to a widow’s life and never remarrying. Then there were the women who’d never even had the chance, the ones who held a dead lover’s letters to their heart every night as the empty years ticked by. If the slaughter was going to repeat itself, there was no question of getting serious about someone when the last communication you received might be an official telegram that read: Madam, it is my painful duty to inform you that a report has this day been received from the War Office…

And if there was to be a war, wouldn’t the theatres shut down? This time, or so the experts said, it would be a war unlike any other, a war of bombs dropped on civilians, of whole cities reduced to rubble. Her fledgling career would be amongst the first casualties.

Then there was the promise of Egypt itself – a pull, if anything was. Its history was as familiar to her as England’s, thanks to Archie’s tales of his adventures with Uncle Nim. Of its recent history she knew only what she had read in the newspapers and heard on the radio: that it had gained its independence in 1922, but that it still maintained strong ties with Britain, even permitting her troops to remain there to protect the vital Suez Canal. She’d read that the new young king, Farouk, was something of a playboy. That there was a nationalist movement that wanted all remains of Britain’s involvement removed. Beyond that, little enough – except that Cairo was home to the Nimrod Theatre. She’d been dying to see it from the moment her father had first mentioned it in his letters.

Besides, it was her duty to help in the search for Archie. Her memories of him had eased the pain of his absence. She had clung to them jealously, using them as a shield whenever her school friends had unthinkingly paraded the virtues of their own all-too-corporeal fathers, whose motorcars, lined up on the school’s drive, had marked out the span of each term like bookends. Archie was her father. She loved him. And now he might be in trouble. What sort of daughter would turn her back at the very moment he had most need of her? The very thought of it made Prim’s cheeks burn.

If there was any doubt, Mr Hanslope’s chestnut mare put paid to it. Somehow, or so it seemed, she had read her rider’s thoughts. Because, without really being conscious of having done anything with her legs or the reins, Prim now realized that they were trotting back towards Larchford Farm. And her mind was made up.

———

‘That’s the most ludicrous thing I’ve ever heard in my life,’ Celestina said later that evening when Prim delivered her bombshell.

The Fraternity had eaten together in the dining room, which they called ‘the refectory’ – because it sounded grand and they weren’t – and were now occupied playing gin rummy in the drawing room. Out of a sense of duty, Prim had joined her mother in the library to hear a talk from the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, about the responsibilities of Empire on the BBC National Programme.

‘How do you propose to even get there?’

‘The same way anyone gets to Cairo: by steamer.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Prim.’

‘I’m being quite serious.’

Celestina switched off the radio set and perched on the arm of the sofa. ‘Look, darling, you really do have to remember that I know all about your father and his little peccadilloes. Trust me, you’ll be far too late to mop up whatever mess he’s got himself into.’

‘At least I have to try, don’t I?’

Celestina ran a hand through her daughter’s blonde hair. It was the sort of calming caress she hadn’t used since Prim stopped falling off her tricycle. ‘I know you were his little girl,’ she said, ‘and I hate to have to be brutal, but he’s probably either floating in the Nile with some tart’s bullet in his head or lying insensible in a hashish den. He might have fooled you and all those clever people at Anglo-Levantine Oil, but Archibald Nevendon never fooled me – at least not since I woke up one morning and smelled someone else’s perfume on him.’

‘I can go by aeroplane.’

‘How will you do that? You don’t have the money.’

‘I’ve got a little bit put by from my last commission. I thought you might help with the rest.’

Celestina stared at her daughter as if she’d suggested they rob Martins Bank in Tunbridge Wells at gunpoint. ‘Me? You want me to fund this insane idea of yours?’

‘He’s in trouble,’ Prim pleaded. ‘I know he is. I have to go.’

But Celestina was unmoved. ‘Archie bloody Nevendon made his own bed a long time ago – several of them, as I know to my own humiliation only too well. He can lie in whichever one of them he chooses, as far as I’m concerned.’

‘Surely, Mummy, you must care a little about what might have happened to him.’

‘Must I?’

‘You loved him, once upon a time.’

‘Once upon a time I had a taste for pasta. Can’t abide the stuff now. I have absolutely no interest in that wretched man, and no intention of funding your foolish jaunt to Egypt. Forget all about gadding off to Cairo, darling. If you’re at a loss for something to do, why don’t you let Angus take you down to a dance in Brighton? You know he likes you.’

‘I’ll find a way, Mummy. You can’t stop me; I’m a grown woman of twenty-four.’

‘Primrose, darling—’

Prim flinched. Her mother only ever called her by her full name when she was about to deliver a lecture.

‘Far be it from me to insult your intelligence, but the nearest you’ve ever travelled to exotic parts is Brighton Pavilion. God alone knows what sort of trouble a young woman could get herself into in Egypt. What if you end up in a Bedouin harem or a white slave-market?’

‘I don’t think the Bedouin have harems, Mother. And Gertrude Bell managed all right, didn’t she?’

Sensing defeat, Celestina changed tactics. ‘Darling, I couldn’t bear the thought of anything happening to you, so far away. I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night for worrying.’

Prim, who had long ago learned to counter Celestina’s appeals to her conscience with practicality, said, ‘I’ll speak to the Cairo police. I’ll go to see Anglo-Levantine. Just being there, I can at least hope to hear some news. I’ll talk to his friends, put advertisements in the newspapers…’

‘I give up,’ sighed Celestina, removing herself from the arm of the sofa and pouring herself a large measure of vermouth from the drinks cabinet, the Italian way – neat. ‘Want one?’ she asked.

Prim shook her head. ‘I’ll find the money somewhere else,’ she said. ‘And I’ll be fine. Don’t worry about me.’

Celestina downed half the glass in one take. ‘Well, that’s going to be easier said than done. But I suppose I can’t stop you, can I?’

‘Not really.’

‘Do we bother with an argument, like the one we had when you went swanning off to Birmingham for that production of Uncle Vanya? I mean, Birmingham of all places, really, darling.’

‘You know I don’t like arguing, Mummy. But I’ve made up my mind.’

Celestina finished her vermouth in two more gulps and slapped the glass down on the cabinet. ‘And I refuse to feel guilty for not indulging you in this insane plan.’

‘I’d rather go with your blessing than without it.’

‘We wouldn’t have this problem if you were married, Primmy,’ her mother said ruefully. ‘There’d be someone to put his foot down.’

Prim looked at her mother from beneath a lowered brow. ‘I’d like to see someone try.’

‘I suppose your next stop will be to visit that dreadful woman in Knightsbridge.’

A daughterly smile from Prim – like the ones she used to give Celestina whenever her mother had seen through some childish evasion, or downright lie. ‘If that’s the only way to get to Cairo, I suppose I’ll have to.’

The next morning Prim caught the slow train to London. She sat in a second-class compartment as if dressed for an interview, because Granny G – Archie’s mother – maintained what she called ‘standards’. The compartment was half-full, mostly bowler-hatted men heading to their anonymous drudgery in the City. Prim had enough space to place her bag beside her on the tartan seat, which was just fine because she didn’t care to be overlooked.

As the pipe smoke hung in the air like the aftermath of an artillery duel, she took out her collection of Archie’s letters and began to read through them. She knew the contents as well as an actor knows their lines. They were precious to her: all she had left of him to cling to.

The early ones, sent when she was a schoolgirl, were chatty – or as chatty as Archie’s formal, businesslike demeanour could manage. The later ones bore the stiff, uncertain taciturnity of a man addressing a young woman he no longer really knew. Typed, not handwritten – he’d always had a jumpy, inconsistent scrawl – they seemed to her now like letters sent from another century.

Once she’d read them all again, she returned them to her bag. Then, taking out her fountain pen and a notepad, Prim wrote a brief letter to Harold Armitage:

Dear Harold,

Sorry to break it to you like this, but I’m sure you knew it was coming one way or the other. I think it’s time to drop the curtain. A short run. We gave it our best. We had some good houses, and I’m sure you’ve had worse reviews. Sorry, but my heart’s not in it.

Yours,Prim

She folded the note into the envelope she’d brought for the purpose and settled back into her seat. Outside the carriage window, the soot-stained brickwork of Victoria hove into view.

Lady Grace Nevendon maintained a genteel but dwindling salon in an echoey apartment off Lennox Gardens, to the south of London’s Brompton Road. Stuffed with outsized furniture salvaged from an impractical family pile somewhere in Gloucestershire, it had the feel of an over-filled antiques shop. Granny G was an elfin woman in her late seventies. Habitually dressed in a flowing silk kaftan and turban, she was the focus for a local coterie of third-tier female aristos too low down the social scale to find a welcome in Belgravia. They met twice a week, rain or shine, to drink Singapore Slings for lunch and lament the present travails of the world, drawn to Grace Nevendon as if she were the medium at an Edwardian séance.

‘I know exactly why you’ve come, darling,’ she said as Prim kissed her on the cheek and caught the dry scent of faded lavender, making her think of old flowers left too long in a church bereft of a congregation. ‘I have a friend at the Foreign Office who telephoned me a few days ago.’

‘Oh,’ Prim replied as she hung up her coat. ‘But you didn’t think to call me?’

‘You know how it is. Celestina might have answered. I do so hate unpleasantness on the line. Can’t abide it.’

‘Aren’t you worried about him?’

‘Of course I am, darling. But what can one do from Knightsbridge? I’ve spoken to a charming Major-General Russell in Cairo – he runs the police there. Took two days before the operators could make a decent connection, but he was as helpful as anything.’

‘And did he have any news?’ Prim asked as Granny G led her into the drawing room.

‘Not really. My bet is that Archie’s gone off on one of his little jaunts into the desert, digging up whatever it was he and darling Nim used to get so excited about when they were young.’ And as if to prove her point, she gestured at the collection of framed photographs she kept on a mahogany drum-table in the window bay. Prim knew each one by heart: Nim and Archie as children, pretending to be archaeologists as they dug in a flowerbed with a trowel too large for their infant hands; Nim and Archie in their army uniforms, standing by the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem; Nim and Archie reclining in wicker chairs on the terrace at Shepheard’s in Cairo; Nim and Archie in sola topees and shorts, leaning into each other and grinning like loons against a background of ancient mud-brick walls. Her boys, forever frozen in the past. Their images had stood on this table for as long as Prim had been coming here, a huddle of tombstones in the graveyard of Grace Nevendon’s memories.

‘We had two police officers come to Bevern Lodge yesterday,’ Prim said. ‘Mummy thinks they were either Special Branch or from the government. They suggested Daddy might have taken what he knows about the oil fields out there and handed the information over to the Italians or the Germans.’

‘That’s ridiculous.’

‘Exactly what we said.’

‘Archie does have a venal side to him – I’m allowed to say that; I’m his mother. But he wouldn’t sell secrets to countries that could become our enemies. He risked his life against the Germans in the last war.’ A pause. ‘His brother gave his.’ She shook her little head. ‘It’s out of the question.’

Sherry schooner in hand, Prim went over to the collection of photographs. She picked up the one of her father and Uncle Nim standing amidst some ruins. There was no way of telling where the shot had been taken. It could have been Palestine, Iraq – Mesopotamia as it had been then – or Egypt. A handwritten note took up the place where a signature would have been, had it been a painting rather than a photograph: TURQUOISE, 1913. The year before she was born, Prim noted. While Celestina had been carrying her, Archie and Nim had been abroad on another madcap expedition to dig for treasures both men knew they would never find.

‘I’ve told Mummy that I’m going to find a way to get out to Cairo to search for him,’ she said, turning towards her grandmother. ‘When I asked for her help, she refused point-blank.’

Grace Nevendon nodded in sympathy. ‘Yes, well, I’m afraid that doesn’t surprise me in the least. I know Archie was less than a gentleman in that marriage. I’d have thought Celestina might have got over it by now; I suppose that’s down to the Latin temperament she inherited from her father.’

‘So I’ve come to you instead.’

Granny G’s moist eyes widened. ‘You’re asking for my assistance in getting to Cairo?’

‘You’re the only one who can help me.’

‘Do you really think that’s a good idea, darling?’

‘Why not?’

‘First, it’s a long way. Second – it’s Cairo.’

‘Granny, it’s a cosmopolitan city. Plenty of people go there. I’ve read about it in magazines.’

Grace looked doubtful. ‘I know you theatre people like to think of yourself as frightfully modern, but Egypt? Come on.’

‘I’m not a child, Granny. I’m not a naïve little girl. I can take care of myself. I’ve survived so far amongst a lot of hotblooded actors and directors. It takes a fair bit to shock me, you know. Besides, if not me, then who else is going to look for him? You’d go, wouldn’t you – if you could; if you thought he needed help?’

Grace Nevendon reached out and took the photo from Prim’s hand. She looked at it for a moment, a thin smile on her face. Whether it was from the memories or the regrets, Prim couldn’t tell. ‘Yes, if I were younger, I suppose I would,’ she agreed. She set the photo back in its place carefully, as though it were too delicate to survive much handling. ‘If I were to help you – and I emphasize if – how do you plan to get there?’

Prim tried not to grin. ‘Well, time is of the essence. The Imperial Airways flying boat service from Southampton to Africa stops at Alexandria. They lay on a train from there. I could be in Cairo within a day and a half of leaving England.’

Granny G allowed herself a sharp laugh of admiration. ‘Good heavens, darling. What a modern world we live in.’

‘But will you help me?’

‘Your mother isn’t going to forgive me for this, you do realize that?’

‘And I wouldn’t be able to forgive myself for abandoning Daddy in what might be his hour of need. At the very least I can represent the family with the authorities. If someone’s there to keep up the pressure, they might work a little harder.’

‘You’re a sweet girl, Prim,’ Grace said, as if she’d only just reached that conclusion. ‘I’m sure Archie would be proud. But have you considered the possibility that he might have got himself into some sort of deep water? He’s always been a very forthright sort of boy. Some people find him rather rich meat. He makes enemies easily.’

‘He’s still my father, Granny.’

Granny G refilled their glasses from the cut-crystal decanter. ‘Chin-chin,’ she said.

‘Chin-chin, Granny,’ Prim replied, desperate for an answer, but trying hard to hide it.

‘What happens if you don’t like what you find? Have you thought of that?’

‘Honestly, I’ve never thought of Daddy as a saint. But if he’s in trouble—’

Grace Nevendon set down her glass and took her granddaughter’s hands in hers. To Prim’s surprise – followed swiftly by a sense of guilt that made her blush – they felt like cold, reptilian claws. It was like something from a fairy tale made to scare children, the clutch of an old crone warning her not to go deeper into the forest. She shook off the notion and gave Grace her best smile. ‘I’ll be fine,’ she promised.

‘Well then, I suppose I ought to fetch my cheque book.’

At the door, as she was leaving, Prim said, ‘Oh, I almost forgot. I’d like you to look after these.’ She reached into her bag and withdrew the wad of Archie’s letters. Holding them out for Granny G to take, she added, ‘Will you take care of them for me? I know it’s silly, but I had the daftest notion that Celestina might have one of her angry episodes and burn them while I’m away. And they’re really all I have left of him – apart from the memories.’

Moussa Bannoudi was about to cross Cairo’s rue Bostane, near the Yugoslav Consulate, when the car pulled up a few paces ahead. He barely gave it a glance. He didn’t recognize it, or the three men wearing Western clothes who lounged so casually in their seats. Nothing to do with him. They’d stopped for someone else. He kept walking.

When the three men stepped out to block his path, he still had no cause for concern. Indeed they waved at him, smiling, as if they knew him. He heard a cheerful ‘As-salamu alaykum’.