6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

The idea of the volume

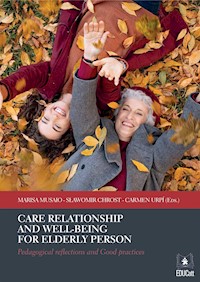

Care relationship and Well-being for the Elderly person: Pedagogical reflections and Good practices, edited by Marisa Musaio, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan and Piacenza (Italy), Sławomir Chrost, Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce (Poland) and Carmen Urpí, Universidad de Navarra of Pamplona (Spain), expresses the intentionality of pooling research and reflections to help raise awareness of a different narration of the elderly condition, to delineate an interpretative, reflective and practical-planning perspective, to support an all-encompassing advocacy towards the elderly person in the contexts of care and educational and pedagogical services.

The contributions that compose the volume converge on a “pedagogy of elder person” that does not indulge in a merely problematizing approach on the difficulties of elderly and advanced old age. Following this idea, Marisa Musaio’s contribution privileges a hermeneutical and interpretative approach to rethink how we see and think of the older adults. This approach helps us to deconstruct the most widespread cultural stereotypes and develop wide-ranging attention, which also requires an interpretation in consideration of gender. A necessary step to develop a way of approaching the elderly person is the interpretation of care as an intrinsically relational task, to help the person address the criticalities of aging, the onset of frailties and any difficulty beyond which the person can continue to take care of themselves, be cared for and promoted in the complete entirety of resources. Beyond any difficulty to be faced, there still remains a person with their history, experiences and memories.

Tratto dall'Introduzione

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

MARISA MUSAIO - SŁAWOMIR CHROST - CARMEN URPÍ (Eds.)

CARE RELATIONSHIP AND WELL-BEING FOR ELDERLY PERSON

Pedagogical reflections and Good practices

Milano 2023

Volume submitted to Blind Peer Review Evaluation

To cite this volume: Musaio, M.; Chrost, S.; Urpí, C. (2023) (Eds.) Care relationship and Well-being for Elderly person. Pedagogical reflections and Good practices. Milano: EDUCatt.

© 2023EDUCatt - Ente per il Diritto allo Studio Universitario dell’Università Cattolica

Largo Gemelli 1, 20123 Milano - tel. 02.7234.22.35 - fax 02.80.53.215

e-mail: [email protected] (produzione); [email protected] (distribuzione)

web: www.educatt.it/libri

Associato all’AIE – Associazione Italiana Editori

ISBN: 979-12-5535-076-7

ISBN ePub: 979-12-5535-102-3

Summary

Research group

Introduction

Marisa Musaio

Cultural images and Pedagogical perspectives on elderly person for promoting Identity and Care

Guido Cavalli

Anthropological and Pedagogical reinterpretations about the elderly

Anna Przygoda

The picture of the Relationship in the Dyad grandparents-grandchildren

Agata Chabior - Sławomir Chrost

The Carer–elderly relationship: theoretical and research references

Natascia Bobbo

Elderly people suffering from chronic diseases: beyond Therapeutic adherence, looking after the Well-being of the elderly person

Monica Crotti

Age-inclusive city: promotion of relational well-being in elderly people

Carmen Urpí - Fernando Echarri - María Teresa Lasheras

Life Lived and Left for Living: The arts at the service of wellbeing and care for the elderly. An art experience in a context of emergency and social isolation

Carmen Urpí

Revisiting Cinema to Connect Generations. A service-learning program for social debate

Glossary

Index of Names

Research group

Natascia Bobbo, PhD in Education, Associate professor in Social and Health Pedagogy, Department of Philosophy, Sociology, Pedagogy and Applied Psychology, University of Padova (Italy). Her main research interests are: Therapeutic Patient Education, Medical Education, Narrative Based Medicine and Medical Humanities, Death Education, Emotional Fatigue and Pedagogy of Care Work. She founded and directs the Journal of Health Care Education in Practice.

Guido Cavalli, Graduated in Philosophy, University of Venice and Parma, with a thesis on “The sacred in Heidegger’s thought”, PhD student in Pedagogy/Education, Department of Pedagogy, Catholic University of Sacred Heart of Milan (Italy), collaborator and editor of Kasparhauser philosophy Journal.

Agata Chabior, PhD in Education, Associate professor, the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (Poland), Faculty of Pedagogy and Psychology, Institute of Pedagogy. Areas of research: Andragogy, Social Gerontology, Social work.

Sławomir Chrost, PhD in Education, Associate professor, the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (Poland), Faculty of Pedagogy and Psychology, Institute of Pedagogy. Areas of research are: Pedagogical anthropology, Philosophy of Education, Pedagogical Relationship, Social Pathologies.

Monica Crotti, PhD in Education, Assistant professor (tenure-track) in General and Social Pedagogy, Department of Human and Social Sciences, University of Bergamo (Italy). Her main research interests are: Intergenerational learning, especially the Relationship between Children and Older people.

Fernando Echarri,Collaborator professor in Visual Arts Education at the University of Navarra (Spain). He holds a PhD in Environmental Education (2009). He is a member of the research group VOICES. Currently Head of the Educational Area of the University of Navarra Museum.

Teresa Lasheras,Director of Music and Performing Arts at the University of Navarra Museum (Spain) and belongs to its board of directors. She has developed her professional career in the management of cultural and artistic services, both in public and private organizations.

Marisa Musaio, PhD in Education, Associate professor in General and Social Pedagogy, Department of Pedagogy, Catholic University of Sacred Heart of Milano e Piacenza (Italy). Member of several international scientific advisory boards, she directs the editorial series “Pedagogia, persona, possibilità”, Mimesis Editions. Her main research interests are: Care and Helping Relationship and Health professions, Life skills education and Care pedagogy for elderly, Aesthetic Experiences and Personal flourishing.

Anna Przygoda, PhD in Education, Assistant Professor at the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce (Poland), Institute of Pedagogy.

Carmen Urpí, Associate professor in Arts and Aesthetic Education, School of Education and Psychology of the University of Navarra (Spain), coordinator of the research group VOICES (Voices of Innovation and Creativity in Education and Society), member of the Ibero-American Society for Social Pedagogy (SIPS).

Introduction

Defining elderly and advanced old age is a complex task by reason of the numerous biological, physical, psychological, pathological, cultural, social, and environmental factors that contribute not just a set of phenomena to be investigated but a delicate age of life and an experience of human enrichment. The pedagogical research in this field is even more complex for the personal dimension that does not allow for reductions and generalizations.

Historically, as still today, the elderly age has been affected by images that associate it with illness and the passing away of life, even though studies show that we currently age better and healthier. However, even if the elderly are more likely to become ill and to incur pathological conditions that specifically accompany aging, we cannot admit the identification of elderly age with illness and frailty. Nonetheless, never before has old age been widely medicalized, identified with an ill body to be treated, a person often deprived of their uniqueness and history, thus preventing us from grasping the complexity of a person. Contemporary culture further focuses on the elderly predominantly from problematic viewpoints, highlighting their fragility and exclusion from social dynamics. The representations and ways of thinking about the elderly age convey stereotypes that prevent an authentic perception and the possibility of recognizing the person from a unified and integral approach.

The pandemic framework has not improved our perception of the elderly person. Due to the considerable difficulties the pandemic entailed, it has yet to foster perspectives and attitudes to help us relate to older people, their residual potential and their creativity.

The priorities of the health emergency have placed the lives of the elderly even more under the influence of risk, danger, and insecurity that have overflowed into their lifestyles, depriving them of the humanizing meanings that we now feel the need to recover.

The long-time pandemic has touched a kind of ‘ground zero’ on various aspects: from assistance to the possibility of ensuring the daily continuity of care, from isolation to loneliness, to the need for an authentic relationship, even though, from other points of view, it has allowed us to understand the profound meaning of human fragility and the educational work of relationship required in different contexts. It is precisely from the awareness of the human and social impact that the framework of pandemic difficulties has determined on the elderly condition that this volume aims to encourage a more in-depth look at the elderly person, care, relationship, and the promotion of ethical purposes concerning this condition of existence. Beyond any emergency, the elderly person requires acknowledgment, attention to the relational dimensions of care and intergenerational bonding, and the activation of measures of protection against future risks. An ability to address progressive aging is also required, together with a purposeful approach to the problem of chronic diseases, and the promotion of the health and quality of life of the elderly in the spaces of the city, with a knowing look also at the forms of their artistic expressiveness. These are the requirements needed to mitigate the consequences of isolation, enhance the sense of solidarity, and activate measures of mutual support.

Accordingly, the condition of the elderly person is to be seen not only as the outcome of factors and conditions that recall the onset of pathologies but also as a set of potentials, resources, and relational skills that synthesize the existential becoming of the person. As Romano Guardini states, old age is the outcome of the “particular tension between the identity of the person and the change in the traits that qualify him or her” (Guardini, 2011, p. 3). Old age, following the events, modifies how one listens to oneself and one’s presence, to the world, to others, to how one lives one’s time and the changes that describe it. The elderly person faces the need to address the inevitable change of self, of one’s body, in being able to look at painful experiences such as illness and suffering, at the “crisis of detachment”, in the light of a broader design. This new perspective allows them to take on the season of old age as a time of revision and change of one’s life project, considering the needs and fragility that inevitably contribute to the re-signification of one’s existence. For these reasons, pedagogical research reflects on the elderly person from an in-depth look that, while recognizing personal, social, and existential vulnerabilities, also knows how to promote the potential of each elderly person.

The idea of the volume Care relationship and Well-being for the Elderly person: Pedagogical reflections and Good practices, edited by Marisa Musaio, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan and Piacenza (Italy), Sławomir Chrost, Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce (Poland) and Carmen Urpí, Universidad de Navarra of Pamplona (Spain), expresses the intentionality of pooling research and reflections to help raise awareness of a different narration of the elderly condition, to delineate an interpretative, reflective and practical-planning perspective, to support an all-encompassing advocacy towards the elderly person in the contexts of care and educational and pedagogical services.

The contributions that compose the volume converge on a “pedagogy of elder person” that does not indulge in a merely problematizing approach on the difficulties of elderly and advanced old age. Following this idea, Marisa Musaio’s contribution privileges a hermeneutical and interpretative approach to rethink how we see and think of the older adults. This approach helps us to deconstruct the most widespread cultural stereotypes and develop wide-ranging attention, which also requires an interpretation in consideration of gender. A necessary step to develop a way of approaching the elderly person is the interpretation of care as an intrinsically relational task, to help the person address the criticalities of aging, the onset of frailties and any difficulty beyond which the person can continue to take care of themselves, be cared for and promoted in the complete entirety of resources. Beyond any difficulty to be faced, there still remains a person with their history, experiences and memories.

In Guido Cavalli’s contribution the causes of the cultural marginalization of the elderly in modern society are analyzed by reconstructing the anthropological opposition between the modern individual and the elderly person. This is accomplished through an excursus of founding texts for modern thought and others that have allowed for an existential and personalistic reinterpretation of the elderly, both in terms of anthropology and in terms of a re-reading of the educational models of care and community.

Agata Chabior and Sławomir Chrost emphasize the analysis of the optimal conditions within the social and living environment that enable the elderly person to live as well as possible. Particular focus is placed on the relationship with carers, reflecting elements such as kindness, responsibility, empathy, and acceptance. The undoubted advantages of establishing a relationship, confirmed by the research results, allow us to identify the prerequisites for future research around relationality and the development of communication skills in the carer-elderly relationship.

Relationality is at the core of Anna Przygoda’s investigation on intergenerational perspective of the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren. This special bond within the family benefits the children, who need educational role references that can help them in important identifications in their future lives, and the elderly as grandparents, who have the opportunity to play the role of “bearers of right models,” expressing strong emotional bonds.

The weaving of authentic relationships, intergenerational ties, openness to the contextual reality and to the extended network of educational, social and community services, are emerging as essential resources to help the elderly deal with the more challenging experiences that inevitably recall the aging processes and the pathological conditions that most frequently arise in the elderly.

In this direction, and in understanding how to help the elderly continue to deploy their residual resources, Natascia Bobbo’s contribution joins in, with a direct focus on the frailties and adversities that can affect the lives of the elderly, particularly those living with a chronic disease. Living with a chronic disease has innumerable consequences that affect the quality of life at any age but can be a particularly disruptive challenge for the elderly. In fact, elderly patients with chronic diseases may be at greater risk of maladjustment than younger patients. As the results of the observational study conducted before and during the pandemic emergency on elderly people with diabetes and osteoporosis show, there is a need to identify which adjustment strategies can be activated by the elderly and what conditions allow or prevent them from doing so.

Against the backdrop of these considerations, the volume keeps a firm focus on the emphasis that the person is not only their frailty, but always remains a set of attitudes, potentialities, creativity, skills, and relationships. Although the road to implementing a promotional approach to the elderly person is in many ways still to be built, as shown by the current epochal phase marked by the pandemic, it is necessary to the condition of the elderly also in relation to poorly investigated dimensions. In this direction, Monica Crotti’s essay investigates the condition of the elderly concerning several issues that recall the role of age-friendly cities. These issues are associated with the importance of quality of life and intergenerational solidarity, indicating how critical educational guidelines are today to recognize the accessibility and inclusion of the elderly within cities and to reflect the assumptions of the care of social well-being even in old age.

The generative and regenerative, inclusive and well-being-promoting purpose of the elderly person is extensively emphasized in the contribution of Carmen Urpí, Fernando Echarri and Teresa Lasheras, with reference the implications between the perception of elderly people and the activities of art museums, the possibilities of re-empowerment of the elderly through projects with a participatory and co-creative character in the arts. While the elderly have traditionally been regarded as targets of museums, theaters and other cultural organizations, they can instead become leading actors capable of taking care of themselves and being cared for by society by claiming a diverse, active and forward-looking role.

The innumerable potentials of the elderly can also emerge from specific artistic forms such as those enclosed in the film heritage, a topic Carmen Urpí dwells on. She aims to promote intergenerational dialogue between young and old, activate service-learning processes on fundamental life issues and enhance their sense of community.

In short, the volume is a multi-voice dialogue on some of the leading emerging issues around the elderly person. The essays cover the multiple dimensions that contribute to defining a condition of life that is not necessarily marked by hardships and emergencies but also by potentials and experiences to delve into as interesting scenarios for scientific, practical, and educational study. A pedagogical reinterpretation reveals the specificity of the humanizing proposal of an education to dimensions, by no means taken for granted, such as care, relationship, promotion of well-being, and attention to the uniqueness and history of each person that can emerge from involvement in expressive and creative activities. As a subject who is no longer merely passive, a receiver of interventions, the elderly person becomes a co-protagonist of experiences, and does more than only request. The elderly person, in turn, is capable of listening, experiencing tenderness, welcoming, and sharing. This set of human attitudes leads research to identify more profound needs present in each person, all the more so when they experience aging processes, changes, and times of suffering.

Marisa Musaio

Sławomir Chrost

Carmen Urpí

Cultural images and Pedagogical perspectives on elderly person for promoting Identity and Care

Marisa Musaio

Abstract

Introduction. Contemporary culture pays attention to the elder people primarily from the problematic point of view of frailty, perpetuating stereotypes and perceptions that prevent the activation of a harmonious and integral approach to the person in a delicate stage of life.

Objective. The contribution proposes a pedagogical perspective based on an interpretative synthesis and interdisciplinary analysis on the elderly person, to combine reflection, care, assistance and practical-planning commitment, in order to raise awareness of a different narration of the elderly condition.

Method. The essay’s starting point is a hermeneutic pedagogy of the older person, attentive to anthropological, ethical, and educational dimensions, and then analyzes the central cultural stereotypes regarding the older adult, showing the importance of their deconstruction in order to elaborate educational and relational purposes.

Results. The hermeneutic investigation makes it possible to highlight how there is not one single old age, but many possible old ages, which implies attention to a multifaceted universe, that requires an interpretation in relation to gender, to elaborate a way of approaching the older person and care as an interdisciplinary task carried out by the various helping professionals.

Conclusion. The contribution points out four dimensions for a rethinking of elderly age: how we see and think of the older adult; tracing the need for a "pedagogy of the elderly"; considering the polarity between frailty and care, in order to move towards the promotion of a specific educational helping relationship with the older person.

Keywords: Aging, Care, Pedagogy of the elderly, Stereotypes, Multiple old ages

1. Approaching the elderly between stereotypes and interpretations of aging

A society of globalization, uncertainty, environmental risk and aging, makes register the grow of complexity and emergency factors. At the same time it is also growing a sense of widespread unease (Bauman, 2018/2002; Benasayag & Schmit 2003/2004), above all in people engaged in experiencing existential transitions and the ages of life that imply a transformation and achievement of new balances (Stoppa, 2021). This happens in adolescence and different elderly ages, the ages of life that par excellence are expressions of desire, in which the experience of one’s own body and the world changes altogether and results in a new feeling for things: while for adolescents it entails learning to inherit from previous generations, for the elderly it means learning to exercise the art of knowing how to fade away.

In his book The ages of desire. Adolescence and old age in the society of eternal youth, the psychoanalyst Francesco Stoppa affirms that adolescence and old age “are the ages in which to say yes to life, in the first case by stepping into the scene, in the second by knowing how to leave it”(Stoppa, 2021).

The progress and innovations of the developed world have enhanced the desire for youth in those experiencing the third and fourth ages. They do have increased opportunities to access lifestyles and well-being, but what is still lacking is a corresponding recognition of older people within society.

These acquisitions do not extend to the so-called “oldest persons” and to those aged 80 years and over, who continue to face a growing stigma and many social stereotypes compared to the third age between 60 and 79 years. Of all the stereotypes, ageism stands out because of the prevalence of standardized and impersonal perceptions about the elderly people (Nelson, 2009; Healey, 2013; Levy, Apriceno, Macdonald, Lytle, 2018). Research and theories that address ageism, studying the effects of discrimination on the elderly people, highlight how essential the role of communication is in the aging process, to enhance people’s capabilities. In fact, differences in social groups and cultural characteristics of communities affect the way we communicate about age. In the meantime, if we place communication at the center of the reflection on aging processes it is possible to focus on those components of uncertainty and negativity that persist around the aging process. We can avoid negative language and treat life changes as an evolving adventure, leveraging on a theory of successful aging that draws on the ecological model of communication (Giles, Gasiorek, Davis, Giles, 2022).

The study of stereotypes around the age and identity of the elderly, considering the influence of culture, gender, ethnicity, or being a member of certain marginalized groups, deals with these dimensions to understand how they contribute to an “intergenerational educational relationship”. The aging representation and how we discuss illness, death and dying in different cultures (Bretelle-Establet, Gaille, Katouzian-Safadi, 2019; Gire, 2014) inevitably affects said relationship, as these themes remain constantly at the margins in a society that delineates itself as essentially amortal (Holmberg, Jonsson, Palm, 2019; Manicardi, 2011). On the contrary, these experiences help promote a relationship paradigm based on the recognition of the older person and attention to their specific life needs. As the aging processes have intensified, the demand for care is increasing as well in that delicate stage of the end of life, which implies an understanding of the life-and-death attitude by the elderly (Lei, Gan, Gu, Tan, Luo, 2022).

The transition from the third to the fourth age, mainly referring to the older persons’ possibility to keep the resilience indispensable to maintain their own position of engagement and autonomy even in old age, proves to be fraught with challenges and adjustments necessary to ensure aging without discrimination (Kydd, Fleming, Gardner, Hafford-Letchfield, 2018), which can be inclusive within society and filled with meaning for the person.

Compared to the other life ages, the older persons experience the primary distinction between age and time: while the former displays the passing of days of which one can only take note, time, on the other hand, is an individual experience, of the imagination, of memory (Minkowski, 2004). While age tends to delimit us between a date of birth and a date of death, time, Marc Augé notes, “is a freedom”, while “age is a constraint” (Augé, 2014, p. 11). Indeed, those who approach old age and advanced old age for research immediately perceive age as a constraint that applies particularly to identifying specific categories of so-called frail people. The risk they otherwise face is of remaining invisible in both a social and cultural sense, drawing attention only in problematic and pathological terms.

The distinction between age and time warns us against falling into easy clichés and stereotypes that unfortunately survive extensively in our society. When we refer to the elderly and old adults indeed, we move from a rhetoric about the wisdom of the older persons, fueled by stereotypes that tend to overestimate the virtues of old age concerning the experience acquired, to an age as a source of knowledge or accumulation of experience. In the interpretations of younger people prevail glossy images typically employed to represent the older persons, up to describe them in a paradoxically infantilized way within the care and assistance contexts where a helping relationship is established with them from medical, nursing, caregiving, educational, and animation points of view.

Trying to untangle the references to images, expressions, and stereotypes paired with the older adults, the impression is that one needs to outline a multidisciplinary and multidimensional approach without, however, disregarding the underlying fact that recalls the lengthening of the average lifespan. Population aging is the top global demographic trend aligned to reach a substantial figure by 2050 due to the increase in the world population over 60 years of age, which will almost double from 12% to 22%1. The forecast for 2050 is that 80% of the older people will live in low- and middle-income countries, registering a much faster rate of population aging than in the past so all countries are facing a set of challenges to ensure health and social systems capable to better address these demographic changes. Accordingly, the interpretation of aging data activates reflections, research, and political decisions, which directly connect with the topic of health, care, and the relationship we can establish with the older persons (Musaio, 2021). However, the need to ask how we consider the elderly, how we interpret a phase of life that thrives on the intertwining of the passage of time and the experience of one’s own age, remains central, but little investigated, in consideration of the fact that, as Augé states, “For each of us life represents a long and involuntary investigation” (Augé, 2014, p. 11), which is not easy to compare with the history, experience and way in which each individual lives their own existence. For these reasons, the author states:

The point of age, experienced by everyone in every aspect ..., and at any age ... represents the essential human experience, the place of encounter between ourselves and others and is common to all cultures. Nevertheless, it remains a complex and contradictory place in each of us […]. Eventually, everyone is brought to question their age, whether from one aspect or another, and thus to become the ethnologist of their own life (Ibid., p. 15).

To those who object that older persons live in the past, thus believing that the passing of time accounts for the discriminating factor to understand the older person’s life experiences, Augé replies that no matter how much we age externally, the core of our essence as persons does not age and remains indestructible. “Old age – the philosopher Francesca Rigotti points out – is not a fault; specifically, youth is not a merit. These are data, facts, not values. Old age is not sand in the mechanism of life, it is life itself” (Rigotti, 2018, p. 118). From these reflections around a possible and different interpretation of old age, it is easy to glimpse a task of research for different sciences, within an interdisciplinary dialogue, in being able to redeem the older person from perspectives and ways of thinking that marginalizing them and not recognizing them for what they really are.

2. Images of old age between positive, negative, and gender perceptions

The image of old age and advanced old age that has emerged over the eras is one of the nucleus problems from which to start a philosophical topos present since ancient times, both in consideration of the conditions of the older adults in times past and in relation to the formulation of images drawn from philosophy, literature, myths, and legends.

Advanced old age has always attracted the attention of writers and philosophers. In the first book of the Republic, Plato records a conversation between Socrates and Cephalus, father of the rhetorician Lysias, observing that, although most men regret youth, old age is in many respects a blessing in that it frees us from physical desire and leaves the mind free for philosophy (Repubblica, 328b-329d). In the Platonic perspective, advanced old age thus constitutes an opportunity to reach human perfection. This consideration also influenced the later reworking of Cicero, who in his work De senectute, imagines an octogenarian speaking. In contrast, the author was sixty-three years old when he wrote the book and completed it shortly before his death. Cicero’s point of view exerted a vast influence in later Western culture by directing that appreciation towards old age that reaches our days, which leads to deeming it the “age of opportunity”.

A positive perception of old age emerges mainly in the thinking of contemporary authors such as James Hillman and Marc Augé, for whom old age exists more in the “perceptions of others”. The Italian psychiatrist Vittorino Andreoli is of the same opinion. In a recent work, he narrates about pain as a mental component and characteristic of the human species. He gives voice, narratively, to the discomfort of the older persons by referring to an older medical professional who finds himself retired for reasons of age but does not perceive himself as changed or diminished in his skills. Although his usual occupations have ceased, and he can longer practice medicine, he manifests a greater awareness of his profession:

And it came to him to think about time, the time that passes and the meanings it takes on, which do not belong to personal perception but acquire a social dimension. […].

He felt no change in himself; he depended on an act that had declared him unable to perform the task he was carrying out, certainly not perfectly, but with a good level of commitment, of interest for the patients, in which he projected himself, sensitive to the pain of others.

Time is a social invention, measured in years. He does not argue about questions of physics: whether time exists in nature or is one of the complications of the human species [...] he limited himself to the difference between his perception of that certain age and the social one that had imposed on him to stay at home (Andreoli, 2022, pp. 294-295).

The positive perception that the older person feels about self-awareness and the professional and human experience learned over time contrast with the negative perception that occurs for purely chronological reasons, almost always dramatically decreeing the older person’s detachment from a context of professionalism, relationships, meanings, which conversely have been important for an extended period of the older person’s life and about which society intervenes sanctioning its end.

The question of how to approach and interpret the older person cannot neglect to consider also the question around the self that crosses the person’s mind, a question often outlined by a sense of loneliness because of the detachment from society, of the fear of being forgotten, abandoned, of no longer having references, with inevitable reverberations on the person’s experiences: “And as time goes by, I have no desire to see anyone, to go out, because I am ashamed, – Andreoli has the elderly doctor protagonist of his narration say – it seems as if I were showing my nothingness, taking it around town, making it evident” (Ibid., p. 303).

With his appeal for a “humanism of vulnerability” Andreoli invites us to recover the essential meaning of certain words such as “old age” which are increasingly emptied of the meaning referring to a wise person and progressively interpreted in relation to the chronological condition of persons over sixty-five years. Because of this factor they are defined as old by a society that relapses the older adults to the canons of the capitalist society of productivity, interpreting them as the ones who manifests a diminished workforce and tends, thus, to entrust their ‘scrapping’ to the State through retirement. By evaluating the human being solely on physical strength, without taking into account their experience, intelligence and acquired knowledge only brings them to feel alienated. The human being cannot be referenced only to the dimension of acquisition and productivity, because their existence encompasses many meanings, and age is not a mere parameter to foster “the scrapping of a person” (Ibid., p. 185).

In addition to being identified with the exclusion from the productive society, the elderly people are mainly considered in relation to the event of death. And given that we live in a society that does not recognize death as an existential condition, but rather associates it only as a condition pertaining to the elderly, it does not therefore recognize that death is a condition proper to the human being, that it is man himself who is destined to die: “Death always happens, no mortal is immortal” (Ibid., p. 184). Consequently, the connection usually established between the older people and death is inconsistent.

In a hermeneutic of the condition of elderly people, we thus verify stereotypes that empty the person of their meaning, reducing their human dignity and the perception of their active potential.

The very use of the term “old” should be sensitive and overhaul those phenomena of infantilization of language that do not consider that “for the old person”, for the person that has been declared old, such a term constitutes a very serious judgment that comes to shatter existence: “The old person is declared useless, legislated without possibility of appeal. Final judgment. The penalty is death, and since they keep calling it back, one ends up wishing for it, which only adds to the sense of uselessness” (Ibid., p. 194).

Going beyond pure rhetoric, the words “old age” and “elderly”, just like other words crucial to our existence, should be used in their simplicity and essentiality. It happens, however, that we use them emptily, words repeated and blended just to put them in order and have the impression that they create a nexus. In reality, we need to return to the meaning of these words so that they can express the human needs, an essentiality that brings us back to the everyday meaning and truth of life that is at once a synthesis of things, activities, experiences, whether beautiful and joyful or painful. For this, we need to trace the prejudices of our time that lead us to consider old age as the age of shame and to forget, instead, that it expresses vulnerability as a dimension that permeates the human condition (Paglia, 2022).

Perceptions around old age register an oscillating trend, projected on a register that is now negative, now positive, or problematical. A polar trend also seems to be found in the considerations by modern psychological sciences, which underline the processes of cognitive and physical decay on the one hand, and the promotion of creative potential and the possibility for the older person to continue their own line of personal development, even managing to reach and overcome the levels of acquisition of youth and adulthood. So, we could confirm the point of view of the poet Paul Valéry about the relationship that the human beings have with time, that involves the activation of a space of possibility, in which the individual acts as a “collector” of possibilities starting from a point that remains stable and which is one’s self:

I am – an incessant contraction of power in the face of the act. The strange movement of this ego, virtual point, is due to the fact that every response close to its point of externalization, speech, movements, etc., produces questions or stimuli – centripetal. I cannot speak without listening to myself – I-spoken inwardly. I cannot move without imagining my displacement. Thus, the ego is to feel that the vitality or activity is not exhausted through a specific act or through an impression. It is the feeling of the reconstitution, or permanence or simultaneity, independence, of powers (Valéry, 1974/1990, p. 433).

The person at the core of their subjectivity remains essentially themselves. Thereby, the approach to be adopted to read their potential, and not only the difficulties or problems they face, requires that we recognize the concept of “ages of life”. Therein, and in the differences between one age and another, we must identify an image and representation of the person such as to preserve the attention to the inner dimension of the single individual who is going through the later ages of life. Everyone, in fact, experiences their awareness and history and certainly needs others, love, friendship, reciprocity. Moreover, as the person grows older, they continue to maintain a relationship with themselves, with their body. Although this is further complicated by age, the person keeps their uniqueness and remains open to new experiences of self in relation to the body, the relationship, the construction of new human relations, the way they experience feelings and their own intimacy (Castiglioni, 2019).

Coming back to the perceptions around old age, it is interesting to consider the growing attention towards the gender dimension about the changing conditions of women’s lives. In this regard, it is possible to trace reflections by female writers who, having dealt with the issue of female identity in the course of their profession, continue to make it a core of research to show the intertwining that old age produces between life, work, and age transitions. This is the case with the studies of sociologist Marina Piazza who highlights the importance of being able to discover, particularly by women, how to deal with this age and the “many possible old ages”, starting from an understanding of the experiences that people record referring the different aspects of their existence:

From throwing the body into space, from getting the measure of oneself in the relationship with others, from being fast, from seizing the ‘moment’, [...] I have moved on to containing time in my body, feeling its heaviness: not only of the body itself, but also of the sedimentation of one’s existences, a stone in the heart that slows down one’s movements – which is the essence of old age (Piazza, 2019, p. 14).

The problematic perceptions around old age, especially in comparison with previous ages, are accompanied, in the case of women, by the difficulties they encounter in entering this new phase of life that indeed transforms people, although it is not an abrupt transition, nor equal for everyone, nor much less homogenous, shared and compact.

Just as with other ages of life, old age is also interlaced with differences, contradictions, and multiplicity, and it could not be otherwise. It is the person, once again, as in younger ages, who is at the center, who is confronted with themselves, with the models around them and also with the absence of models, because in fact, there is no standard model of old age applicable to each and everyone, but, rather, a mixture of perceptions, experiences, sensitivities that come from our lives and from the reflections we have made. The images of old age to be investigated are therefore those that guide us to perceive the “difference” in people’s lives: