11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

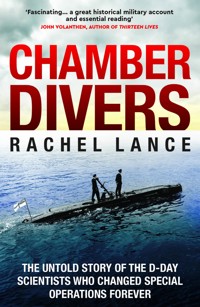

'Fascinating...a great historical military account and essential reading' John Volanthen, author of Thirteen Lives. The untold story of the D-Day scientists who changed special operations forever. On the beaches of Normandy, two summers before D-Day, the Allies attempted an all but forgotten landing. Of the nearly seven thousand Allied troops sent ashore, only a few hundred survived the terrible massacre, and the reason for the debacle was a lack of reconnaissance. The shore turned out to be impassable to tanks. The Nazis had hidden obstacles in unexpected places. The fortifications were more numerous – and deadly – than imagined. The Allies knew they needed to take the fight to Hitler on the European mainland to end the war, but they could not afford to be unprepared again. A small group of eccentric researchers, experimenting on themselves from inside pressure tanks in the middle of the London air raids, explored the deadly science needed to enable the critical reconnaissance vessels and underwater breathing apparatuses that would enable the Allies' dramatic, history-making success during the next major beach landing: D-Day.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Praise for Rachel Lance

‘A riveting account of the daredevil Allied researchers who made advances in underwater warfare possible during WWII… Propulsively narrated and full of moments of astonishing sacrifice, this brings a remarkable history to light’

Publishers Weekly

‘Meticulously researched, the unbelievable yet true story of the eccentric, maverick submarine scientists, whose courage and expertise ensured the success of D-Day. Inspirational reading’

Helen Fry, author of MI9 and The Walls Have Ears

‘Rachel Lance has produced a gripping, beautifully researched narrative that plunges readers deep into the drama of one of the most important military operations in history’

Alex Kershaw, New York Times bestselling author of Against All Odds

‘An illuminating account of the women and men whose dogged efforts and sacrifice helped to enable and protect the most critical, but also most fragile, weapon in war – the human body’

General Stanley McChrystal, US Army (Ret.), author of Team of Teams

‘With skill and heart, Rachel Lance tells the story of a group of unlikely heroes, who sacrificed their own bodies to advance a hidden world of warfare’

Nathalia Holt, author of Rise of the Rocket Girls and Wise Gals

‘In this bracing history of an obscure but significant aspect of the D-Day landing, Lance combines a staggering amount of research with an array of compelling personalities to tell an unforgettable story’

Booklist

CHAMBER DIVERS

Rachel Lance

To my grandpa

Earl Strawbridge Lance,

1924–1999

NCDU team 10,

who specialized in rocket launchers and

underwater explosives

and pushed me for hours on the rope swing

he built in his yard

Contents

Cover

Praise for Rachel Lance

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE: “A Piece of Cake”

CHAPTER 1: Professor Haldane and Dr. Spurway’s Problem

CHAPTER 2: Brooklyn Bridge of Death

CHAPTER 3: Devil’s Bubbles

CHAPTER 4: Subsunk

CHAPTER 5: Love, Cooking, and Communism

CHAPTER 6: Drunk and Doing Math

CHAPTER 7: Everyday Poisonous Gases

CHAPTER 8: The Blitz

CHAPTER 9: The Piggery

CHAPTER 10: The Littlest Pig

CHAPTER 11: Lung Maps

CHAPTER 12: Nerves

CHAPTER 13: The Inevitable Solution

CHAPTER 14: The Midget Subs

CHAPTER 15: Airs of Overlord

CHAPTER 16: The Operations

CHAPTER 17: The Longest Days

CHAPTER 18: The Unremembered

Acknowledgments

Footnotes

Notes

Bibliography

Credits

Index

Also by Rachel Lance

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

“A Piece of Cake”

DIEPPE, FRANCE

AUGUST 19, 1942

657 DAYS UNTIL D-DAY

The operation started with a simple cup of stew. By 0400, everyone had finished their hot, hearty breakfasts and begun to prep grenades. Thousands of warriors dressed in muted greens swayed with the rolling gray decks of the ships of the convoy beneath the meager light of the stars. Closer to the coast, the large ships split apart. The troops would attack at six separate locations.

Once nearer their location, British officer Captain Patrick Anthony Porteous helped his soldiers into position in the small, flat-bottomed boats that would take them the rest of the way. The propellers churned into motion. They headed for the chalky cliffs forming the dark skyline, a slight breeze from the stern nudging them landward.

The destination for Porteous’s group was a sloping, pebbly shore code-named “Orange Beach II,” located inside a curving hook of land in the northeast of Normandy, France. Their target cliffs tapered down to the west of the small resort town of Dieppe, and the other landing beaches—code-named “Yellow,” “Red,” “White,” “Green,” and “Blue”—lay to their left, in the east.

Porteous and his soldiers had watched tracer rounds briefly track across the skies during an unplanned encounter with armed trawlers during the Channel crossing, but the continued welcoming blink of a lighthouse onshore indicated that the scuffle had not triggered any alarms among the Germans. It was lucky because, for this group, that lighthouse was the primary means for navigation. They had limited maps, and no other visible beacons.

The Orange Beach party was divided into Groups I and II, and their joint objective sounded simple: silence the big guns in a reinforced artillery battery high on the cliff. If the battery was left intact, the German troops inside could lob mortar after gigantic, explosive mortar at the other five Allied beach locations, including the main landing sites. Group I would shimmy up a rain-carved gully in the cliff face and distract the enemy from the front. Group II would land to the west and sneak around behind. Porteous and his thirty soldiers, who formed half of F Troop of the British Number 4 Commando, had been designated part of Group II.

Captain Porteous had no idea what the true mission of the entire raid was. But like most soldiers, he knew that his role was not to reason why. His role was to destroy his assigned battery.

Group I landed without enemy opposition, guided in by the lighthouse. They used handheld tubes of explosives called Bangalore torpedoes to create a passageway up the cliff, blasting apart the thick nests of barbed wire that stuffed the narrow slot. A recent downpour had washed away the layer of dirt hiding most of the land mines, and under the moonless sky the soldiers picked their way over the safer patches of soil.

Group II was not as fortunate. As soon as Porteous and his commandos touched ground, the enemy opened fire. Machine guns tore through the night. Lightning-like bolts from tracer rounds showed that most bullets went above the commandos’ heads, but still they dashed across the pebbly shoreline.

To be trapped on an exposed, featureless beach was death. The longer the soldiers lingered without cover, the longer the Germans had to aim. The warriors of Number 4 Commando unfurled coils of chicken wire over the barbed wire blocking their exit from the beach, ran across these makeshift bridges, and dove down the steep drop on the far side. Somewhat protected in a small fold in the ground, they took a moment to regroup before proceeding inland.

No more than twenty of the two hundred in their party had fallen on the beach, fewer than predicted. A medic volunteered to stay behind, but the rest had strict orders: leave the dead and injured. Get off the beach, regardless of casualties, “regardless of anything.” They moved inland.

Group I’s gunfire from the front distracted the soldiers in the battery as hoped, while F Troop and the rest of Group II wound their way around, single file, silent, through a small passage in the hefty barbed wire guarding the back of the concrete monstrosity. Porteous and his troops lobbed explosives inside, killing the German soldiers and silencing their guns. Porteous was shot twice, once through the hand and once in the thigh, but he survived, as did most of Number 4. Their mission was a success.

However, theirs would be the only victory the Allies could claim that day in 1942. By the time Number 4 and their freshly taken German prisoners evacuated from the base of the cliff at 0815, with the wounded Captain Porteous in tow, they were faced with new horror. Thick layers of smoke obscured their view, but the raging thunder of machine guns and mortars at the other landing locations forced a brutal realization. Their compatriots were caught in the worst hell imaginable. Everyone else was stuck on their beaches.

Every snowball begins first as a harmless flake, a diminutive nucleus of crystallized water that, given a downhill nudge, quickly accumulates power. At Dieppe, one nudge was a case of mistaken identity.

In the dark, Gunboat 315 looked an awful lot like Gunboat 316. And by the time the Royal Regiment of Canada, headed for landing site Blue Beach, recognized the error and realigned behind the correct vessel, they were sixteen minutes behind schedule. The Royal Air Force had dropped a thick layer of smoke to obscure the aim of any Germans who happened to be awake, but by the time the tardy Royal Regiment arrived, the punctual smoke had begun to clear.

Aerial planning photographs taken months earlier had revealed the batteries gracing the tops of the cliffs, but the top-down views hadn’t hinted at the surprises in their vertical faces. The Royal Regiment landed on Blue amid the parting smoke and looked up to a nasty revelation. The shelling that had started on time at the other beaches had roused the Germans, and the Germans were not only awake; they had dug into the very cliffs themselves, creating machine-gun-filled nests burrowed into the sides of the steep white walls. They unleashed a furious thunderstorm of metal onto the Allies below.

The few Royals who survived the initial mad dash across the impossibly broad shore hunkered into small shapes, curled helpless against a meager seawall, hoping that the ships offshore and pilots in the air could take aim at the machine guns and mortars mowing them down. But it was hopeless. The officers on the ships couldn’t see through their own protective smoke screen. The pilots in the air, who were not equipped with rockets, struggled to hit the tiny targets dug into the cliff face with guns. Those down on the beach couldn’t fire upward and around corners into the machine-gun grottoes. Bullets and grenades peppered their sky.

Not a single soldier made it off Blue Beach. Almost half of the five hundred in the charge died. The unit had a casualty rate of 97 percent. But, since the Royal Regiment never got off the beach, they also never accomplished their goal: destroy the battery at the top of their cliff.

Other batteries in front of the main landing approach resisted Allied attack, too. In order to get to the town, the rest of the troops would have to run south across broad, open, unprotected beaches Red and White, with active guns crisscrossing their path. The deaths of the warriors at Blue, and the intact battery above them, were a snowball, and they triggered a crossfire avalanche. About a thousand of the Allied landing troops were British, but more than four-fifths of the 6,086 total were Canadians, with only about fifty Americans. What happened next is considered one of the most horrifying disasters in Canadian military history.

The inexperienced Canadian troops headed for Red and White were convinced that tanks alone would provide the power needed to break through the German defenses. Everyone would jump out of the ships together—the engineers with their packs full of explosives, the soldiers on foot, and the fearsome new tanks nicknamed “Churchills.” The soldiers would face down the guns while engineers blasted paths through the barriers blocking the exits from the beach; then the Churchill tanks would proceed smoothly and easily through those paths into the town. Their commander, General John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts, had even promised in his prelaunch pep talk that it would be “a piece of cake.”

An aerial photograph of the cliffs above Blue Beach, taken a few years after the raid. The gun caves are still visible in addition to the batteries along the top. (NARA photograph)

With this plan fixed in his mind, Dutch-born noncommissioned officer Laurens Pals of the 2nd Canadian, on board an impressive tank-carrying ship, confidently prepared to land on beaches Red and White. He did not know that the flanking batteries remained intact.

The barrage was instant, and staggering. The tanks had been waterproofed with a thin material, but their carrying vessels were not bulletproof. Both got riddled with projectiles. The vessels began to sink; the tanks began to swamp. Some coasted to land too crippled to function; others burbled to the bottom of the sea, drowning the people inside.

The process to unload the tanks was slow. The beasts were cumbersome, and soldiers on foot were stalled by tending to the monsters as they rolled out. The struggling clusters of troops provided dense stationary targets for hungry German gunners.

The combat engineers carried explosives to clear paths, but their ordnance caught fire when hit by bullets. Some engineers were forced to throw their flaming piles of munitions overboard, while others pressed on, knowing they were human bombs. All of these specialized soldiers were in the first wave of the assault. All were mowed down. As a result, paths were never cleared. An official report described the problem bluntly: “The road blocks were never destroyed because of the failure of Engr [engineering] personnel to reach these blocks alive.”

With the deaths of the engineers, no matter what, the tanks were blocked. However, the Churchills had never been used in combat before, or even thoroughly tested, and the beach itself proved another unexpected obstacle. The waterfront was made of pebbles, billions of smallish rocks polished smooth by the eternal grinding of the waves, and the rocks got stuck in the tanks’ exposed gear mechanisms. The tanks threw off their tracks. Almost all got stuck, at least one flipped over, and several somehow caught fire. Every single tank was destroyed. Some of the troops had been equipped with bicycles so they could travel farther into the town, and these, too, sank feebly into the pebbles. Almost nobody was able to clear the broad, steep shores.

When Laurens Pals landed, he took what cover he could in a small divot in the sloping ground. When ordered to advance, he dashed to a second small hole. From there he could see the street where he was supposed to start his specific mission during the raid. He would never reach it; the opposition was too great. A haze of death filled the space between. Dodging mortars and machine guns, he dove behind a landing ship that had tipped over, joining dozens of troops who had been shot. He helped establish a sort of field hospital in the cover of the sideways vessel. Pals and the others hunkered down and tried their best to survive the ongoing hailstorm of bullets, periodically darting out to drag more wounded and dead behind their improvised protection.

Laurens Pals was charged with a secret mission. He had been ordered to sneak into town, aided by a select handful of explosives-carrying engineers—all now dead—and steal a big yellow code book out of a hidden safe. There were others also charged with intelligence-gathering missions, and these missions were the true purpose of the entire raid. The Allies hadn’t wanted to bomb the town of Dieppe beforehand and risk destroying the fragile information they sought. But the official explanation for the lack of bombing was that it was hard to teach pilots to aim properly in such a short amount of training time.

So, because of the lack of bombing, the intact, beautiful residences along the waterfront stayed packed with machine guns and machine gunners. These gunners, too, fired at Laurens Pals every time he ran out to retrieve more wounded and dead from the bloodstained waves.

Desperate to accomplish the secret missions and gather intelligence from the town, the commanders offshore continued to send wave after wave of new troops to Red and White in the hopes that a few individuals would manage to break through and maybe find a code book or an encryption device known as an Enigma machine. The new model of Enigma was being used by German submarines to receive encoded messages and wreak havoc in the Atlantic. However, the reinforcements served only to add to the growing piles of Allied bodies strewn about the rocks. At 1100, after hours of abuse, the exhausted and battered survivors finally received a radio transmission ordering them to surrender.

The convoy offshore never sent ships for an evacuation. One group of sailors made an abortive attempt, but their lone vessel got overwhelmed by enemy fire and too many troops trying to scramble on board. They managed to evacuate only a small fraction. The rest were abandoned. Slowly, the screams went quiet.

Under pressure from the Russians to open a second front in the west to divide and distract the Germans, and under pressure from the Americans to try an invasion of the European mainland, Winston Churchill had reluctantly permitted the raid on Dieppe. Churchill had already been part of one beach debacle, when during World War I he had been responsible for a failed beach-landing attempt on the Gallipoli peninsula in modern Turkey. The travesty had resulted in 250,000 casualties stretched out over nearly a year of misery without resolution. He knew the Allies were not yet ready to assault beaches, but when pressed, the infamously fractious leader had been willing to prove his point in blood.

Ham Roberts, the commanding general of the 2nd Canadian who had made the quip about cake and kept sending in reinforcements to die, fled his home country. He would allegedly receive an anonymous parcel on his doorstep containing a single stale piece of cake on the anniversary of the raid every year for the rest of his life.

In the weeks following the massacre, when the tides had finally washed the blood off the pebbly shores and the Allied news media lied to pretend it had been a victory, the Allies would title the key section of their official report simply, with the most optimistic veneer they could muster: “Lessons Learnt.” The Dieppe “Lessons” report is unequivocal in its language: “As soon as it is known that a project involving a combined operation is under consideration”—meaning an operation like an amphibious invasion that combines sea and land—“the question of beach reconnaissance in all its aspects must be investigated.”

At Dieppe, landing ships had encountered underwater obstacles for the first time. The obstacles were fearsome-looking constructions of steel and explosives designed to tear and blow apart the ships from beneath. Landing parties needed to know if such obstacles waited beneath the waves. Perhaps most important, the report emphasized that they needed to do the scouting stealthily so they could keep the element of surprise: “Naval reconnaissance methods should also be used but care must be taken that they remain undetected.”

However, the report does not mention what kind of undetectable naval scouting methods should be used. Possibly because, in the fall of 1942, most were unaware if any such methods existed. The militaries’ only knowledge of the composition of the beaches at Dieppe had come from a photograph that someone had taken during a vacation trip years before the war—a photograph that showed finely clad ladies and gentlemen enjoying a day of relaxation onshore. The Allied officers had simply sent the tanks in and hoped for the best.

One of only three scouting photographs of White Beach, all of which were taken before the war.

The Allies learned that to achieve a successful large-scale beach invasion, to have a chance at bringing the fight to Hitler on the European mainland, they would need real intelligence: solid and up-to-date information about the positions of the guns, the slope of the shore, the type of sand or rocks, and the locations of obstacles or land mines. They needed a plan for navigation that didn’t rely on the luck of German-held lighthouses remaining lit—they needed detailed maps and the ability to send undetectable scouts who could place markers and beacons in advance. They were willing to throw bodies at the problem, but to succeed, they would need both bodies and cunning. They would need to send reconnaissance troops ashore. And the best way to do that, they realized, was to hide them under the ocean waves. To make a beach landing possible, they needed warriors equipped to survive underwater.

Fortunately, a small group of scientists was already on the case.

CHAPTER 1

Professor Haldane and Dr. Spurway’s Problem

Afew days later in London, a resonant hiss vibrated through a narrow metal chamber as pressurized gas gushed in. The enclosed steel tube was a cramped, heavily riveted cylinder with thick walls and rounded ends, a mere four feet in diameter and laid down sideways on a platform in the corner of an industrial warehouse. Pneumatic pipes sprouted from the top like mechanical antennae. Inside, wood planking formed a humble, flat floor, and even when curled up on that planking in a sitting position, Professor John Burdon Sanderson Haldane took up most of the chamber’s white-painted internal volume. Six foot one and unintentionally, awkwardly, massively imposing, the blunt yet mostly affable middle-aged geneticist had broad shoulders, a hefty mustache, and a prominent bald forehead that forced his bushy eyebrows downward at the seeming expense of his eyes. He sat staring across the narrow space at today’s test subject: Dr. Helen Spurway. The gas roared around them. The chamber began to heat.

Twenty-seven-year-old Spurway, herself a PhD geneticist, was as lanky as Haldane was robust. She perched on a small stool opposite the prof, her slim shoulders forced into a curve by the tubular white walls. She had short dark hair with a subtle natural wave in it, cut into a practical bob that would have been easy to dry after getting in and out of the water repeatedly for diving experiments. Her smooth, heavy brows formed a sharp frame within her pale face to offset deep brown eyes, and gave her the animated look of someone who not only listened but scrutinized. For today’s test, her nose was pinched shut by a spring-loaded clip. Her lips were sealed around a rubber mouthpiece that was connected through two large corrugated hoses to a square-shaped, flexible tan bag strapped to her chest. It was an apparatus designed to deliver pure oxygen to her lungs.

Haldane and Spurway’s goal was to see how long she could breathe the oxygen before it began to poison her. She was an eager test subject. The poisonous effects of oxygen become far worse under high levels of pressure, and she wanted to use her own body to puzzle out how bad they could get.

Roaring air continued to force its way into the small steel chamber, which was dimly lit on the inside by the paltry warehouse lights shining through its one pressure-reinforced porthole. The intruding air drove the internal pressure levels up to those felt by divers swimming deep in the ocean. The temperature climbed as more gas pushed and compressed itself into the small space, and the heat became unmerciful, exacerbated by the thick, syrupy sensation of the newly densified atmosphere. Haldane and Spurway, pressed together by the unyielding confines of the chamber walls, sat curled close enough to watch each other sweat.

The hiss of the gas, deafening at first, began to taper slowly as they reached their target pressure, but even as it slowed the reverberations caused by its flow remained the dominant sound inside the white metal tube. At increased gas densities, such as the pressures inside a hyperbaric chamber, houseflies cannot take flight. People cannot whistle. Voices become cartoonishly high-pitched, increasing in frequency alongside the temperature and density. Breathing and movement acquire a conscious feeling as the thickness of the air deepens.

Haldane and Spurway reached a pressure level equal to ninety feet beneath the waves, as well as a scorching heat somewhere in the triple digits Fahrenheit, and an operator outside the chamber spun a valve to halt the inward rush of gas. New sounds pinged through the cooling metal tube as the chamber operators manipulated the gases to maintain the depth, while the temperature inside began to drop. Haldane noted the time.

Five days after Dieppe, not yet knowing of its horror, Haldane and Spurway were already unwittingly working on the next amphibious assault plan. The tan leather breathing apparatus Spurway wore on her chest was called a Salvus, and in a world before the invention of the now ubiquitous SCUBA, she was trying to figure out how long it could be used safely by swimmers and submariners beneath the surface of the ocean.

After precisely thirty-three minutes of sitting in the chamber calmly, patiently sucking down oxygen, Spurway yanked the rubber mouthpiece from her lips. She vomited. She vomited repeatedly. Later, she reported that she had been having visual disturbances beforehand: brilliant flashes of dancing purple lights she referred to as “dazzle.” She gulped down chamber air, no longer on oxygen, and recovered slowly. Thankfully, today’s symptoms were mild. Watching her gulping, gasping face, Haldane again noted the time.

Professor Haldane, Dr. Spurway, and the other members of their small clan of scientists had spent the last three years grinding away within the close confines of these hyperbaric metal tubes at the myriad questions surrounding underwater survival, with the initial goal of enabling sailors to escape from submarines. Their leader, Haldane, believed firmly that human beings provided better feedback than research animals.

Shortly before the disaster at Dieppe, but not in time to stop it, the scientists had been asked to pivot this work to focus on a new, more specific goal. The Admiralty had called. To help their countrymen and the Allies defeat Hitler, to help end the war, the Allies needed the scientists to use this same work to prepare for beach-scouting missions. There would be another beach landing. And the next one could not fail.

Decades before the experiment, a thirteen-year-old boy peered out of the tiny reinforced window cut into the side of a metal chamber, gazing at the small crowd of adults watching him back through the clear, hefty panel. This small hyperbaric chamber sat on the deck of a Royal Navy ship rolling with the waves off the coast of Scotland. As the hiss of gas filled his chamber, the towheaded boy practiced moving his jaw and swallowing to allow the air to enter the spaces inside his ears. He succeeded, proving he could clear his ears. He reached the maximum pressure safely, and was returned to the surface pressure without harm. After the circular chamber door swung open, the boy clambered carefully out onto the deck in the hot, late-summer weather. His father began to strap him into a sturdy canvas suit sized for an adult while the sailors and other researchers watched. It was time for the boy to have his first dive.

The boy, John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, was born in 1892 into the sort of Scottish family whose summer homes have turrets. Stately portraits of ancestors with facial-hair topiaries or dresses with miles of pleated fabric grimaced down from the high walls of their multiple estates, and manicured lawns and gardens buttressed the elaborate stonework buildings. But John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, called “Jack” in his youth and later “JBS” as an adult, had no patience for such pomp. He insisted on keeping an old bathtub full of tadpoles beneath the arcing branches of one majestic apple tree, within which he was determined to breed water spiders.

His immediate Haldane family’s little team of four—himself; younger sister, Naomi; mother, Louisa Kathleen; and father, John Scott—formed one branch of a venerable lineage that stretched its documented pedigree back to the 1200s. As children, Naomi and Jack were bred into science the way some are bred into royalty.

Their parents, Louisa Kathleen and John Scott, seem to have gravitated toward each other because of the same fiercely independent, socially irreverent genius they would pass on to their children. She was a brilliant young woman with golden hair, classical beauty, an affinity for small dogs, and an outspoken confidence that, along with her propensity for the occasional cigarette, marked her as a rebel within the prim upper crust of 1800s Britain.

She stumbled across John Scott for the first time when he was asleep on the floor. He was a lanky young man with deep, kind eyes and a dark, full mustache, and she walked in on him sprawled on a rug in front of a fireplace, drooling into a scattered mountain of books. She and her mother were thinking about renting the Edinburgh home from the Haldanes for the winter, and John Scott was supposed to show them around.

He couldn’t convince her that he had been awake, but he did convince her to marry him. Born stubborn enough to be independent and wealthy enough to stay independent, she relented only after negotiations. After rejecting him twice, Kathleen finally accepted Haldane’s third proposal on the condition that he would not try to dictate her personal political views.

It stormed on their wedding day, and John Scott showed up late to his own ceremony in her parents’ Edinburgh drawing room because he had gone back home to grab a forgotten umbrella. The bride, however, being equally utilitarian, did not mind. The ceremony was already planned to be short because Kathleen had tracked a blue pencil line through most of the dumbfounded minister’s boilerplate script. She and John Scott were both firm agnostics and unafraid to buck convention, so she refused to wear lace, and she “strongly objected to the farce of being ‘given away.’”

After the wedding Kathleen promptly moved in to John Scott’s home in Oxford, England. He was a physician and professor of physiology at Oxford University, and the infamously eccentric researcher had already converted the basement and attic of the house into makeshift laboratories. There he could play with fire and air currents and gas mixtures. So could his children.

Eleven months later, it was into this kind of world that infant Jack was born. At one point as a baby, he screamed so forcefully that he gave himself a hernia, which unofficial scientist Kathleen calmly reduced herself. Sister Naomi was born five years later. A few years after Naomi’s birth, the finished quartet moved along with Kathleen’s mother to a larger, “comfortable and ugly” custom-built thirty-room mansion christened Cherwell. This building’s entire design revolved around the pursuit of science, no longer limiting it to the attic and basement.

John Scott insisted that the bathtubs be made of lead for better thermal insulation. He refused to allow the installation of gas lines because he considered gas too chemically explosive. He and Kathleen packed every room with cozy chairs for reading and intellectual curios such as scarab beetles or painted Chinese bowls stocked with goldfish. John Scott’s large office extended off the back of the house, and it was perpetually encrusted in a mosslike coating of books and papers. It held a room-length wooden table big enough to do the glassblowing required to make custom chemistry equipment, and a small step led down to their in-home laboratory. The lab had large windows looking out onto flower-filled gardens, and the walls were braced by broad shelves full of chemicals and supplies. The lab always featured at least one airtight gas chamber, just large enough to hold a person, nicknamed “the coffin.” It could be flooded with any gas desired. It often was.

Even the family cat slept curled, tightly but voluntarily, inside a beaker in the lab, and Naomi’s dollhouse was decorated by famous scientists. Nobel Prize–winning physicist Niels Bohr was among those who had contributed, bringing a little toy jug for her miniature estate.

Carved into the entryway stonework of the house was the Haldane family motto, one hovering word that would become an ominous portent. To enter the Haldane home, as if crossing the threshold of a new, far more foreboding world, all visitors and guests were required to pass under the simple declaration:

SUFFER

The two children were inseparable. Naomi and Jack chased globules of mercury across the laboratory floor, huffed chloroform and giggled at its effects, sucked in a miscellany of strange gases from storage bottles to test the effects on their voices, or simply whirled together dancing Viennese waltzes until the giddy spinning rendered them too dizzy to continue. He called her his “Nou.”She addressed him as “Boy”; “Boydie,” a contraction of “boy dear”; or sometimes just “Dearest.”

“As children we were both in and out of the lab all the time,” Naomi once wrote. They didn’t need to sneak in; they and their father were the only three allowed. Naomi’s job as a child was to monitor the test subjects through the observation window in the gas chamber and, should they fall unconscious, to drag them out and resuscitate them. By age three, golden-haired, chubby-cheeked toddler Jack was a blood donor for John Scott’s investigations, and by age four, he was riding along with his “uffer” (father) in the London Underground while John Scott dangled a jar out the window of the train to collect air samples. The duo found levels of carbon monoxide so alarmingly high, the city decided to electrify the rail lines. Already, as a toddler, the younger Haldane was learning how to keep people alive and breathing in worlds where they should not survive.

By age four, Jack was also exploring coal mines with his father to figure out how people breathed in those cramped, dangerous spaces. Frequent explosions and gas leaks made mining one of the most lethal jobs in the world, and gentleman physician John Scott Haldane became known among the miners of the country for his willingness to clamber into the narrow, dark, coal-filled passageways on his mission to make the air supplies safer. “Canary in the coal mine” is still a common expression to describe early detection of any threatening situation, and using the small, chipper birds to detect gas leaks was John Scott Haldane’s idea.

Every time a mine exploded, John Scott—and often his son, Jack—hopped on the next train to sift through the corpses and wreckage to find the cause. With every trip, young Jack watched his father practice firsthand what seemed to be the elder professor’s most important lesson: volunteer yourself first; then, after you went, exclusively test on “other human beings who were sufficiently interested in the work to ignore pain or fear.”

They chose to make informed consent their policy, in a time period so ignorant of the concept that physicians joked openly that it was easier to find volunteers for experimental surgeries than for experimental medical treatments because the unconscious surgical patients could not decline. Testing on animals was the absolute last resort, John Scott lectured, and he even designed a canary cage that would seal itself and resuscitate the coal mine birds with fresh oxygen the moment they fell off their perch.

From his mine trips, John Scott would send home periodic telegrams to reassure his family, but often the carbon monoxide inside postexplosion mines would temporarily addle him so badly, he would write the same words multiple times in one message, forget he’d already sent a message and send multiple repeats, or write entire messages of gibberish. (Kathleen did not find these telegrams reassuring.) To study the effects in a slightly more controlled manner, he sealed up his home gas chambers and willingly breathed levels of carbon monoxide that pushed him deliriously close to death.

Naomi wasn’t invited on the field trips, mostly. She had a heart-shaped jaw, broad cheeks, a button nose, and signature Haldane golden ringlets spilling down her back. But Naomi was born a daughter in 1897, and so she was born a disappointment to her patriotic mother, because girls were considered less useful to the British Empire at a time when the Empire was the loftiest of concepts for the aristocrats of England. Kathleen and John Scott were feminists by any definition, but even the most ardent advocates for equality recognize that their ability to raise their children on an even footing within their own home far exceeds the level to which they can demolish the bias of the outer world at large. It is possible to see the value of a young woman yet understand the arbitrary and brutal shackles the world will force upon her. The world that Kathleen knew in 1897 would look straight through Naomi’s genius or find it inappropriate. Indeed, despite the fact that Naomi grew up to be an extraordinary and prolific author as well as a vital key to adult JBS’s future science, most biographers omit or minimize her. Even Kathleen’s own memoir contains a beefy chapter titled “My Son” while only sparsely describing Naomi. Naomi summarized the end effect: “Certain avenues of understanding were closed to me by what was considered suitable or unsuitable for a little girl.” Young Naomi was denied access to the paradise where Jack got to play.

However, she crept her way in. Naomi might not have been welcome in the mines or on the boats, but within the walls of their homes, she was mostly an equal. From her, Jack would learn firsthand the intellectual equality of women—a principle that he would absorb and apply with fervor, and one that would allow him to build a spectacular future lab during a war-driven shortage of eligible men.

Naomi demanded that other children in her preparatory school participate in the family science, giving brusque orders like “You come in here. My father wants your blood.” A diary kept by Naomi at age six has colorful, meticulous illustrations of begonias with details about counting the petals to tell the sex of the blooms (a “she-begonia” versus a “he-begonia”), all written in the large, looping calligraphy of a child.

When Jack was eight years old, John Scott brought him to an evening lecture about Mendelian genetics, a set of mathematical explanations of how physical traits get passed down between generations—why some siblings turn out blond but others brunette; why some pea plants have violet flowers but others white. Science had not yet pinpointed the primary culprit as DNA. Jack became obsessed with the cutting-edge idea. Naomi had begun keeping guinea pigs after a nasty fall left her afraid of her pet horse, so they started using her carefully trained fuzzy “pigs of guinea” to test the theories of gene propagation themselves, along with mice, lizards, birds, and whatever other fast-breeding animal they could procure.

Soon the front lawn of their home teemed with a roiling carpet of three hundred guinea pigs, all carefully labeled, numbered, and partitioned behind wire fencing. The squeaking fuzz balls had been deliberately bred, observed, and documented so that the young scientists could compare the patterns of their whorls and colorful splotches against Mendel’s math. They executed the calculus to describe the patterns of inheritance in their guinea pigs at a time when most adults were unaware that such fields of research even existed. Through this exploration, Jack Haldane learned statistics. He learned probability.

The two developed a perspective on the world that was based on an innate need to understand how it worked, a need to tease apart its inner mechanisms and find what drove the microcosmos, the animals, the planets, and the stars. Naomi said her favorite part of the day was opening the mouse cages and letting “the darling silky mice” wander over her in her specially designated blue mouse-tending frock. Years later, during WWI, when adult JBS saw some odd, hairy-tailed rats at an undisclosed forward combat location in Mesopotamia, he gushed in a letter to his sister about how he “would like to Mendel them.”

As a child, Jack Haldane played with strange gases and saw their effects on test subjects in the sedate, controlled environment of the home gas chamber. He began to learn how breathing gases affected people under the menacing pressures of water.

Jack—soon to be JBS—Haldane was the next heir in a line of respiratory researchers trying to puzzle out the mysteries of the human body under pressure. People had been trying, and failing, to figure it out for decades. One of the first puzzles of life underwater was the mystery of decompression sickness, and this mystery was what had landed thirteen-year-old Jack inside a small hyperbaric chamber, trying to clear his ears against changing pressures, rocking on a Royal Navy ship near Scotland. He wanted to be part of the diving. The Haldanes were on this ship to prove that John Scott had answered the first major question of survival in the deep. However, long before the younger Professor Haldane and Dr. Spurway sweated in their chamber in 1942, even long before the elder Haldane’s experiment in 1906, the question of decompression sickness had been forced into consideration.

CHAPTER 2

Brooklyn Bridge of Death

On February 28, 1872, two decades before J. B. S. Haldane’s birth, Brooklyn Bridge laborer Joseph Brown was submerged well below the murky waters of New York City’s East River . . . technically. The twenty-eight-year-old American-born foreman sloshed through a shallow layer of dark, frigid water in his work-issued, thigh-high black rubber Goodyear boots, but the rest of him stayed dry, free to hoist a pickax or a sledgehammer beneath the low ceiling and bring it down with enough force to remove yet another hunk from the rocky sand of the moist river floor.

Caissons are massive constructions that look a bit like large rectangular wooden bowls. They’re turned so the open mouth faces downward, and they get plunked into the water beneath a layer of hefty building material thick enough to ensure that they plummet firmly to the bottom. Once they have settled onto the topmost, waterlogged layer of unstable earth on the river floor, workers use gas pumps to push air down into them from the surface, and that compressed air blows out the water from inside the inverted bowls. The workers are then free to travel down into the wooden structures and dig inside, working the edges of the caisson downward inch by painful inch into the muck and soil as they remove bucketfuls of stone and earth from below. Each caisson used for the Brooklyn Bridge was thirty-one by fifty-two meters in size, divided into six long chambers by internal walls. They were sizable hunks of a city block beneath the waves, but with no sun, and with impenetrably thick, flat, iron-reinforced wooden skies looming only three meters overhead. Brown, like so many others, sloshed inside.

Harper’s Weekly illustrations of caisson work for the Brooklyn Bridge.

The dark, soggy, air-filled crawl spaces had floors of mud and sand and were peopled by “sand hogs”—workers wielding pickaxes, chisels, sledgehammers, and shovels. As the sand hogs dug, the knife-edge perimeter of the bowl crept downward, the crushing weight of the tower above held at bay almost exclusively by the upward push of the pressurized air within. More layers of stone were arranged carefully on top of each caisson as it sank, and these layers became the pillars of the bridge, creeping their way from the river floor downward to the bedrock like the probing roots of a massive stone tree. When the workers hit bedrock, they would evacuate, the empty space inside the caisson would be filled with cement, and the entire monolith would be left in place as a support for the stable thoroughfare above.

Inside a caisson beneath the Missouri River, 1888.

The humidity of the river mingled with Joseph Brown’s sweat and the evaporated stench of the laboring crew around him. Most of the workers had long ago peeled off their shirts, or they had gone down without them in the first place. The air temperature around them rose to tropical levels with each swing of their tools, even as their feet froze from the chill water, and they could feel their headaches slowly build as they breathed and rebreathed the same air inside the enclosed space. Brown and the rest of the roughly sixty-person working crew were at the end of their third hour inside the humid, dimly lit, wooden-walled caisson. For foreman Brown, it was the end of his watch. It was hot. It was humid. It was time to come up. He headed for one of the ladders.

A particularly brutal winter in 1867 had iced the East River, the obstacle between Brooklyn and Manhattan, and left the ferryboats locked at their piers. After that difficult winter, the people of Brooklyn had decided they wanted a bridge to Manhattan. But not just any bridge. With the East River more of a broad, active tidal basin than a river, stretching an immodest five hundred meters across, it would need to be the longest suspension bridge in the world. So it would need burly supports on either end to keep it strong. And in order to let ships pass under the bridge freely, each of those supports would need to be the tallest construction in America at that time—excepting a few stray church spires and the Statue of Freedom, which nudged the Capitol Building in Washington, DC, to a few feet of advantage.

To keep out the river, the air inside a caisson needs to be at least the same pressure as the water outside. So, as the depth of the roots increases, the pressure in the air increases, too. Joseph Brown’s caisson was on the deeper, Manhattan side of the bridge. Far beneath the river, just like inside a pressurized chamber, the compressed air was thick. Because of the increased density, voices rose in pitch. Here, again like in the chamber, it became impossible to whistle. And it became dangerous. On February 28, 1872, Joseph Brown had been unknowingly working just beyond the cusp of where that pressure could become a deadly problem.

Brown and his crew, exhausted, shirtless, sweaty, filthy, and covered in river mud, climbed up the rungs of the stubby ladder and into the lock embedded in the roof of their caisson. The lock was a sturdy chamber in the shape of an upright cylinder, and it could hold up to thirty workers when densely packed. Once the last worker clambered up through the hatch in the floor of the lock, they closed and secured it behind them.

Finally, after hours at work beneath the suffocating body of the East River, the workers could see the sky again through the small reinforced window inside the opposing hatch in the lock ceiling. Only after the gas space of the lock was depressurized to the same pressure as the air outside could that upper door swing open, but then the sand hogs would be able to climb up the winding spiral staircase to fresh air, hot coffee, and freedom.

First, a crew member turned on the heating mechanism, which would send scalding steam flowing through the metal coils attached to the interior walls of the lock, in anticipation of the humid, bone-penetrating sort of cold that fills any space containing rapidly expanding air. The coils began to warm. Then the lock operator slowly and ever so slightly cracked open the brass valve to vent the pressurized air. The hissing scream of traveling gas dominated while the pressure dropped. Steam condensed out of the very air itself, an eerie and frigid indoor fog. The lock approached the lower pressure level of the outside world. Then the trouble started for Joseph Brown.

At first he thought that he was fine. It took about ten minutes to vent enough gas to reach surface pressure, and after that, he climbed out of the lock and up the long, twisting route toward daylight. Little is known about what he did next, but perhaps he relaxed at the top, or drank a cup of hot broth offered to him by the on-site doctor. Perhaps he jumped into a carriage to head straight home. But whatever choices he made, almost precisely one hour after leaving the caisson, a sudden stabbing bolt of agony rippled through Joseph Brown’s left shoulder and arm. Pain ran through his joints and along his nerves like lightning, “like the thrust of a knife.”

Nothing relieved the vicious pain, and nothing would. Not twisting his hand, not massaging the joint, not a “drachm” of ergot—a small dose of a medically unhelpful hallucinogenic fungus that grows on wheat—that he might have been prescribed by the bridge physician Andrew Smith. Brown simply lived with the hot, throbbing, jagged, penetrating neurological sensation of stabbing fire until the next afternoon, when he needed yet again to go down into the damp, murky depths in order to make a living.

Immediately when he reached the bottom of the river, the pain disappeared. His arm was healed; it worked as it should; he had no discomfort. He blissfully completed his shift, and he came back to the surface again, in the lock, slowly. This time, after the ascent, he had no issues.

The next day Joseph Brown’s arm still remained mostly pain-free, but it was covered with tiny red speckles. Freckles of blood had popped up like confetti on the parts of his arm and shoulder where yesterday’s pain had screamed the loudest. He reported to the bridge doctor Andrew Smith that those areas were slightly sore and slightly numb, and Dr. Smith was perplexed. Smith logged Brown’s strange symptoms in his notes. For months Smith would continue to wonder about their cause.

As the project progressed, the medical cases seen by Dr. Smith began to increase in tempo. More workers from each shift emerged from the caisson to become bent and contorted with often crippling pain. Each surfacing of the lock became the beginning of an ominous period of waiting for catastrophe to strike. Dr. Smith began recording everything obsessively, trying to understand, trying to treat, trying to figure out the pattern, trying—but failing—to save the workers from the mysterious ailment.

John Roland took a hit on March 8. While in a horse-drawn car and going home, he felt suddenly dizzy, lost all his strength, and could not stand. His feet were cold but his head was hot and he began sweating the disturbing, cold perspiration of an immune system fighting a demon. He recovered on his own within a few hours.

Hugh Rourke was next. On March 12, he, too, was going home when his right knee felt the telltale stabbing of knives deep inside the joint that left him suffering through the night. Rourke turned to morphine for relief. It became an addiction.

The deaths began in April, when the caisson roots stretched beyond sixty feet deep. German immigrant John Myers was the first on record. He dropped dead without warning after leaving a shift, having mentioned only that he was “feeling oppressed by the impurity of the air.” Patrick McKay collapsed the next day, unconscious, while walking down Roosevelt Street, having just left work. He was carted to a local hospital where he died in agony. His death was labeled “congestion of the brain” by perplexed physicians.

By May, a mere month before the pressurized work was done, when the caisson was nearing its deepest depths, the trickle of cases bloomed to a flood. On May 2, James Hefferner had pain, projectile vomiting, and extreme constipation. On May 4, Thomas Kirby had severe pain and swelling of the right arm. The sand hogs began to strike, demanding three dollars for every four hours of the dangerous work, instead of their previous rate of $2.43. On May 8, German immigrant Bruno Wieland was hit with pain, vomiting, loss of bladder control, temporary paralysis, and inability to stand or walk. They got their wage increase.

Then Dr. Smith wrote one medical case report that would provide more information and more useful clues than all the others. Yet ironically he did not list the victim’s full name. He wrote: “Reardon, England, 38.” His report is simple but brutal: “Began work on the morning of May 17; was advised to work only one watch the first day, but nevertheless, feeling perfectly well after the first watch, went down again in the afternoon.” Determined to work a second shift, Mr. Reardon refused to give his body the acclimation and trial period the doctors recommended. He refused to wait to see how his body responded to its first day of pressure. And so, after a morning of 2.5 hours hacking away at the river bottom, seventy-eight feet beneath the water, the stubborn Mr. Daniel Reardon, his full name known only through his death certificate, ate his lunch and climbed back into the shaft for a second shift.

It was his undoing. Immediately after his second depressurization, Reardon “was taken with very severe pain in the stomach, followed by vomiting,” and that pain quickly escalated. It spread to his legs. Within minutes, he was paralyzed from the waist down, but still feeling the agonizing fire. Unable to move his limbs, he could feel rivulets of pain coursing through them, excruciating stabbing needles from the wrath of increased pressure released too quickly. It could not be controlled by morphine. Daniel Reardon died the next day after having vomited through the night, having felt no release from the chronic lightning bolts of agony that made him twist and bend his body into strange and terrifying shapes.

Reardon, unlike the others, had an autopsy. When the doctors cut him open, they saw that his lungs were engorged, filled with the fluid and phlegm produced by a body struggling for breath. His spinal cord was “intensely congested,” meaning that it showed a telltale eruption of blood just above the nerves that, in life, should have controlled the movement of his legs.

Still, he was not the last. By June the newspapers were reporting the deaths with an air of fatigue. On June 18, laborer James Reilly’s paralysis and critical medical state were announced under the worn-out-sounding headline “The Caisson Again.”

The average sand hog on the Brooklyn Bridge lasted only three weeks on the job. Most wandered off without notice, either too hurt or too scared to continue. Although they were referring to other construction accidents, too, the newspapers called it “the Bridge of Death.”

CHAPTER 3

Devil’s Bubbles

The mysterious disease is now called decompression sickness, abbreviated DCS and more commonly known as “the bends.” While the disease in its severest form can indeed force victims to contort their limbs and spine in agony until they look “completely bent up,” its name originally started as a joke. The earliest known victims had milder cases from working in the lower pressures of shallower, less impressive bridge supports. These first workers started with minor pains and twinges, and to alleviate the issues, they sometimes walked with an odd, warped posture. The posture looked similar to the way rich women would warp their backs to bend forward and accentuate the bustles of their fancy dresses, a posture known as “the Grecian bend.” So, to mock them, the affliction became known as the bends. The joke became less funny when the caissons reached depths where the pressures began to cause paralysis and death, but the name stuck.

The devil of DCS is nitrogen. The odorless, colorless, otherwise harmless gas with its large, lazy molecule forms 79 percent of the air around us, and because the insides of the caissons were filled with nothing but pressurized air, nitrogen formed 79 percent of that, too.

Normally nitrogen is a bit of a good-for-nothing gas. Made up of two tiny nitrogen atoms tied to each other in triplicate, it’s a generally stable chemical, happy, almost boring. It’s too heavy to use to fill a good dirigible, too stable to burn and give off pretty colors. It’s not even interesting enough to make a good poison like carbon dioxide, or provide a funny smell like methane. Nitrogen is the boring neighbor on the cul-desac, smiling to everyone from its lawn, always ready to loan its garden tools to carbon when carbon wants to build a tree or a flower. Through its quiet existence and predictable early bedtime, nitrogen makes its neighbors oxygen, helium, and hydrogen look like wild partiers in comparison, with their balloons and their explosions, because—mostly—nitrogen just sort of exists.

Sometimes, however, it’s the quiet neighbor who turns out to be the serial killer. And in the caissons, once the nitrogen reached high enough pressures, the depths became John Wayne Gacy’s murder basement. The nitrogen crept in quietly while the sand hogs were at work. It oozed its way from their lungs into their bloodstreams with every normal-feeling breath, then from their blood into the cells of all their other tissues. Muscles. Fat. Joints. Nerves. As the workers chipped away at the rocks and the mud and the sand, silently their tissues grew soggy with dissolved nitrogen.

By the end of the unprecedented bridge construction and the unprecedented pile of dead bodies it produced, bridge physician Andrew Smith had deduced that the problem was nitrogen. Nobody knew exactly how the gas was getting into the workers’ cells. Still, as of this writing, nobody knows how, exactly, nitrogen behaves as it does inside the body. But gases inarguably have some way of diffusing inward, of creeping across barriers, of leaking into and out of all containers, including the cells of the human body. Somehow, while Joseph Brown and the others were hacking away at the mud and the boulders of the river bottom, the nitrogen crept into them.

After the workers let the nitrogen ooze for three hours, spending a scant few minutes decompressing was not enough to let it back out without a fuss. With every cracking of the brass valve to release the pressure in the lock, the pressure within the workers’ cells was also released. Suddenly loosed from the pressure dam keeping it in its prison, the nitrogen roared back as a flood. Tiny bubbles cascaded out and got lodged in the smaller passageways of the body, wedged themselves in, refused to move, refused to reabsorb, and, most important, refused to let any fresh oxygen-carrying blood pass by. DCS did not happen to every worker, and it did not happen on every ascent. But for those it struck, it caused mayhem.

The tissues, deprived of oxygen, would start to die, and in their scream of death, they would throw out jagged daggers of pain. Some, like survivor Joseph Brown, were lucky, because their bodies managed to carry on, to absorb the bubbles over time, to return to normal function. Others, like Daniel Reardon, were not. The bubbles lodged against their lungs, in their hearts and kidneys, and sometimes in the delicate nerves of their spinal cords. They caused difficulty breathing, cardiac arrest, paralysis, and death. The bodies, when opened up, were filled with bubbles and congestion, visual proof that the pain was caused by nitrogen-induced clogging and chaos.

The doctors knew that the risk and severity of the “caisson disease” increased with increasing pressure and increasing time. Some suspected the root cause was nitrogen, but nobody could prove it, and worse still, nobody could prevent or treat it. That is, of course, until the Haldanes came along. The Haldanes, who spent their lives breathing weird gases.

For young Jack, the home gas chamber was a sanctuary, and science time with his mustachioed father, John Scott, was his favorite escape. The tall, strong, self-described “fat” boy was relentlessly bullied at boarding school. The older boys physically beat him, sometimes every day for weeks, and they also found endless other ways to torment the socially odd, atypically brilliant young man. They chanted mocking rhymes about a small patch of white hair he had on the back of his head. When his uncle and namesake, John Burdon-Sanderson, visited, Jack missed seeing him because the other boys had pinned him beneath a flipped table loaded with bags of sand.

Sometimes he would respond to the bullying with dramatic losses of temper, which further encouraged the sadistic bullies to treat him like a spectacle who could be needled into hilarious explosion. On one occasion he tore an entire sapling out of the ground, including the roots, “and attacked his tormentor with it.” After flinging down the uprooted tree, Jack stormed into the classroom, fuming out loud, “I wish I could kill. I wish I could KILL.” He would never explain to his parents why he hated the school; his mother knew only that “