Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

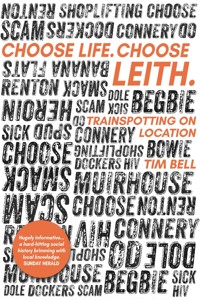

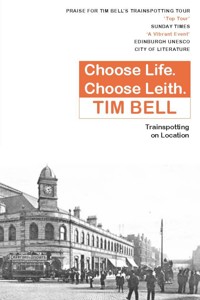

By examining the book, the play and the film, Choose Life. Choose Leith. both critically analyses the Trainspotting phenomenon in its various forms, and contextualises the importance of the location of Leith and the culture of 1980s Britain. Looking in detail at the history of Leith, the drug culture, the spread of HIV/AIDs, and how Trainspotting affected drug policy, Leith and the Scottish identity, the book highlights the importance of Trainspotting. Choose Life. Choose Leith. acts as a reference book, a record of the times and a background as to the history that led to the real-life situation and the publication of the book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TIM BELL is a speaker, writer and tour guide. Raised in rural Northumber-land, he travelled in the Middle East and North Africa as a young man before settling in Scotland to work with young people with special needs. After gaining a Bachelor of Divinity at the University of Edinburgh in his forties he became a chaplain, first in a prison and later in the port of Leith. He began his highly acclaimed tours under the banner ‘Leith Walks’(www.leithwalks.co.uk) in 2003, and has since taken hundreds of people through the streets of Edinburgh and Leith, exploring Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting on location. Tim has lived in Leith with his family since 1980.

Praise for Choose Life. Choose Leith.:

Tim Bell’s Choose Life. Choose Leith. is a very timely book. Well written, insightful, carefully crafted. BERT STEVENSON

Tim Bell ‘gets’ the dynamic that made Trainspotting a publishing then social phenomenon in the 1990s… the understated style of the author gently persuades the reader of the literary merits of the work and its various interpretations but also how it reflected the reality of its locations… Irvine Welsh has found the Boswell for his Johnson. GORDON MUNRO, THE LEITHER

As entertaining as it is shocking, Tim’s attention to detail and ability to bring the past back to life is fantastic. Highly recommended. STEPHEN BENNETT

A real joy to read. DAVID BLOOMFIELD

Many who enjoyed Trainspotting will be astonished at what is revealed here concerning all that lies behind Irvine Welsh’s best known work. IAN GILMOUR

Praise for Leith Walks:

Top tour. SUNDAY TIMES

A vibrant event. EDINBURGH UNESCO CITY OF LITERATURE

Enlightening, entertaining and very knowledgeable, Tim really helps the place and the story come alive. COLM LYNCH, 14 JUNE 2018

If you love the book or the film or both this is a tour you need to take. LARS, 23 APRIL 2018

Tim will make you see the story with different eyes. ANJA, 15 JANUARY 2018

The man is a fount of knowledge, with rich political and social perspectives on the book and its location, as well as insightful critical views of both book and film. COLIN SALTER, 26 AUGUST 2017

What an unexpected pleasure! LORRAINE WHELAN, 11 JULY 2017

If you have any interest in Trainspotting or the history of Leith Tim is the man to talk to! ALI, 8 JANUARY 2017

Tim’s tour of Leith was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. EMMA, 24 AUGUST 2013

[Bell] is at once warm, didactic, and encyclopaedic… he does an excellent job at describing selected scenes within the context of the surroundings. CAMILLE BOUSHEY, THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER

Praise for Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting:

Irvine Welsh’s grimy novel of addiction has emerged as the public’s favourite Scottish novel of the past 50 years. LIZ BURY, THE GUARDIAN

Irvine Welsh’s writes with skill, wit, and compassion that amounts to genius. He is the best thing that has happened to British writing in decades. NICK HORNBY

The voice of punk, grown up, grown wiser and grown eloquent. SUNDAY TIMES

The best book ever written by man or woman… Deserves to sell more copies than the Bible. REBEL INC

An unremitting powerhouse of a novel that marked the arrival of a major new talent. HERALD

A page-turner… Trainspotting gives lies to any notions of a classless society. INDEPENDENT ON SUNDAY

First Published 2018

Reprinted with minor updates 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-73-1

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Maps © David Langworth [email protected]. Map base © OpenStreetMap contributors (www.openstreetmap.org), available under the Open Database Licence (www.opendatacommons.org) and reproduced under the Creative Commons Licence (www.creativecommons.org).

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Tim Bell 2018

To my dear long-suffering wife, Liz,who makes many things possible.

Trainspotting

1. The practice or hobby of observing trains and recording the numbers of the seen locomotives

2. The act of injecting heroin; so called because of the mark or track line left on the affected vein

3. Referring to Irvine Welsh’s 1993 novel Trainspotting, and its lasting legacy of the ‘Trainspotting Generation’ – the over 35s impacted by the 1980s heroin and HIV era

Contents

Acknowledgements

Maps

Timeline

Introduction

SECTION I: By Leith Central Station They Sat Down and Wept

Chapter 1 Leith Central Station

Chapter 2 Leith Junkies

SECTION II: Composition, Threads, Tensions, Structures

Chapter 3 First Generation Episodes

Chapter 4 Second Generation

Chapter 5 The Bastard Twins

Chapter 6 David Bowie, Soren Kierkegaard and the Professionals

Chapter 7 The Music Trail

SECTION III: Trainspotting on Location and Character Profiles

Chapter 8 Leith, Edinburgh, Scotland

Chapter 9 There was an Irishman, a Dutchman and a Scotsman

Chapter 10 Maistly Rubble Nou…

Chapter 11 Meanwhile in the Schemes

Chapter 12 Welsh’s Women

SECTION IV: Heroin, Dealers, Sex and HIV/AIDS

Chapter 13 God’s Own Medicine

Chapter 14 From Eden to Leith

Chapter 15 Needles and Sex

Chapter 16 God’s Own Wrath

SECTION V: What sort of book?

Chapter 17 Is Welsh Scottish?

Chapter 18 Influences, Context and Genre

SECTION VI: Trainspotting the Play

Chapter 19 In-Yer-Face Theatre

Chapter 20 Origins and First Year

Chapter 21 Analysis of the Play

Chapter 22 Aftershocks

SECTION VII: Trainspotting the Film

Chapter 23 The Making of the Film

Chapter 24 This Film is About Heroin

Chapter 25 Character

Chapter 26 Broader Appeals

Postscript

Glossary

Bibliography

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Over the 15 years spent writing this book, many people have generously shared with me their knowledge and insights of Trainspotting and its surrounding issues. In the following pages, some of the extended conversations I have had with people who have supported the project are not directly referenced. Conversely, some chance remarks have been more or less quoted verbatim or greatly expanded. Some people have wished to remain anonymous, for a variety of legal, professional and personal reasons. Thank you all – you know who you are.

All those years ago two people gave me a secure start, which has led to the whole thing growing legs and wings to the point where it is finally published: special thanks go to John Paul McGroarty and Mary Moriarty.

Thanks are due to Thomas Ross, formerly of Luath Press, and present editor Alice Latchford. Years ago I played club hockey with Gavin MacDougall, Director, and we had no idea then that it would come to this! Thank you, Gavin, for your support and encouragement, in various forms, over several years.

Finally, to Irvine Welsh, who couldn’t know what he was starting way back in 1993, thanks for the ‘scabby wee book’ as he later called Trainspotting. For me it has been the perfect platform to combine my interests in community, culture, and words on a page. It’s better than scabby, Irvine. It’s ground-breaking.

Leith map: annotations.

1. 397 Leith Walk: formerly Boundary Bar.

2. 298 Leith Walk: formerly Tommy Youngers Bar. Renton meets Begbie in ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

3. 180 Leith Walk: formerly The Volunteer Arms. Scene for ‘A Disappointment’.

4. 7-9 Leith Walk: The Central Bar. Taken to be the pub ‘at the Fit ay the Walk’ in ‘Courting Disaster’.

5. 398 Easter Road: The Persevere Bar. Scene at the end of ‘Na Na and Other Nazis’.

6. 31 Duke Street: The Dukes Head.

7. 13 Duke Street: The Marksman. Davie Mitchell boards the bus here in ‘Traditional Sunday Breakfast’.

8. 17 Academy Street: Leith Dockers Club. Scene at the end of ‘House Arrest’.

9. 2 Wellington Place. Irvine Welsh lived here.

10. New Kirkgate Shopping Centre. Renton shops here in ‘The First Day of the Edinburgh Festival’.

11. Trinity House.

12. South Leith Parish Church (Church of Scotland).

13. St. Mary’s Star of the Sea Church (Roman Catholic).

14. 58 Constitution Street: Port o’ Leith. Bar where Welsh often met his writing group; clearly re-named Port Sunshine in Porno.

15. 44a Constitution Street: Nobles Bar

16. 63 Shore: formerly ‘the dole office’. Spud sits near here in ‘Na Na and Other Nazis’.

17. Cables Wynd House, better known as the Banana Flats. Sick Boy lives here (ref in ‘House Arrest’).

18. 23-24 Sandport Place: formerly The Black Swan.

19. 43-47 North Junction St: The Vine Bar. Presumably the pub referred to at the end of ‘Station to Station’.

20. 72 North Fort St: formerly Halfway House.

21. 284 Bonnington Road: formerly The Bonnington Toll

Leith Central Station. The most emphatically identified location in Trainspotting. Scene of the ghostly figure’s remark: ‘keep up the trainspottin mind’ in ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

Seafield crematorium and cemetery. Taken to be the place of the funeral in ‘Memories of Matty’.

Leith Academy. Renton and Begbie attended school here.

Fort House. The Renton family used to live here before moving to a flat ‘by the river’ (Water of Leith) (ref in ‘House Arrest’).

Edinburgh/Muirhouse/Leith map annotations.

1. 3 Drummond Street: formerly Rutherford’s Bar. Scene of ‘The Elusive Mr Hunt’.

2. 17 Market Street: The Hebrides. Bar where Tommy meets Davie Mitchell in ‘Scotland Takes Drugs In Psychic Defence’.

3. Calton Road exit from Waverley station. Renton begins his journey here in ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

4. Formerly the GPO (Post Office) on Waterloo Place. Kelly and Alison are here in ‘Feeling Free’.

5. 17-23 Leith Street: formerly Housing Department advice centre. Kelly and Alison are here in ‘Feeling Free’.

6. 43 Leith Street: Black Bull. The steps outside and the street alongside are the most accessible and recognisable Edinburgh location in Trainspotting the film.

7. 19 West Register Street: Café Royal. Seems likely to be renamed Café Rio in ‘Feeling Free’.

8. 21 Rose Street: formerly The Cottar’s Howff. Said to be the scene for ‘The Glass’.

9. 124-125 Princes Street: formerly John Menzies stationery shop. Scene of Sick Boy and Renton entering to do some shoplifting in Trainspotting the film.

10. 435 Lawnmarket: Deacon Brodie’s Tavern. Scene of the first celebration after the court hearing in ‘Courting Disaster’.

11. 9-11 Grassmarket: Fiddler’s Arms. Presumably the pub referred to on the bus to London in ‘Station to Station’.

North Bridge/South Bridge (‘The Bridges’) and Royal Mile. Sick Boy cruises here in ‘In Overdrive’.

Hibernian Football Club stadium. Derby match against Heart of Midlothian (Hearts) played here in ‘Victory on New Year’s Day’. Spud considers going in ‘Na Na and Other Nazis’.

Albert Street. ‘former junk zone’ Renton refers to in ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

Montgomery Street. Renton lived here – see ‘The First Day of the Edinburgh Festival’. See also ‘The First Shag in Ages’ and ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

The Playhouse. Renton walks past here in ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’.

St Andrew Square bus station. Main characters board the bus to London here in ‘Station to Station’.

Charlotte Square. Venue of the Edinburgh International Book Festival.

Scott Monument. Sick Boy shows a photograph of himself and his girlfriend taken here in ‘House Arrest’.

Former Sheriff Court House. Scene of Renton’s and Spud’s court hearing in ‘Courting Disaster’.

Tollcross. Johnny Swan’s flat is here in ‘The Skag Boys, Jean-Claude Van Damme and Mother Superior’.

The Meadows. Scene of ‘Strolling Through The Meadows’.

Milestone House, 113 Oxgangs Road. The hospice where Alan Venters lies mortally ill in ‘Bad Blood’.

Haymarket station, Dalry Road. Renton and Dianne are here in ‘The First Shag in Ages’.

Caroline Park House/Royston House. Source of the confusion of local names that puzzles Begbie in ‘A Disappointment’.

West Granton Crescent or ‘the varicose vein flats’. Renton visits Tommy here in ‘Winter in West Granton’.

Pennywell shopping centre. Renton walks through here and loses his suppository here in ‘The First Day of the Edinburgh Festival’.

Craigroyston School. Spud attended school here (ref in ‘Speedy Recruitment’).

Timeline

1875 Hibernian FC founded.

1903 Leith Central Station opened.

1920 Leith amalgamated with Edinburgh.

1952 Leith Central Station closed.

1957 Irvine Welsh born.

1964 Leith Kirkgate demolished.

1971 President Richard Nixon declares drug abuse to be ‘public enemy number one’, subsequently widely referred to as the opening of his ‘War on Drugs’.

1974 First new-style professional drug dealer charged in Muirhouse.

1979 Margaret Thatcher becomes Prime Minister.

1982 Nancy Reagan’s ‘Just Say No’ first coined.

April – June: Falklands War.

1983 Murder of Sheila Anderson, Leith.

First two known cases of HLTV-3 (or Gay-Related Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome [GRIDS]) in Scotland.

1985 51 per cent of a sample of intravenous drug abusers in Muirhouse found to be HLTV-3 positive.

HLTV-3 renamed Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV); and a group of symptoms that can result from an HIV infection named Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).

1987 ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ leaflet distributed throughout Britain.

Edinburgh dubbed ‘AIDS Capital of Europe’ in a newspaper article.

Needle exchange set up at Leith hospital.

1988 Waverley Care Trust founded.1 December established as World AIDS Day.

1989 Leith Central Station demolished.

1990 John Major becomes Prime Minister.

1991 Calculated per capita HIV+ people in England: 25 per 100,000; Scotland: 35 per 100,000; Lothian Region 144 per 100,000.

Milestone House, Edinburgh, opened as an end-of-life hospice for HIV+ people.

1992 Forth Ports Authority (owners of Leith docks) privatised.

1993Trainspotting the book (Irvine Welsh) published.

1994Trainspotting the play (Harry Gibson) premiered.

1996Trainspotting the film (Danny Boyle) premiered.

1997 Scotland votes in a referendum in favour of devolution.

1998 Former Royal Yacht berthed in Leith; now visited by around 300,000 visitors a year.

1999 Scottish Parliament inaugurated.

2003Porno, sequel to Trainspotting, published.

2012Skagboys, prequel to Trainspotting, published.

2013 Fort House, Leith, home of fictional Mark Renton, demolished.

Trainspotting voted the favourite Scottish novel of the last half-century in a world-wide survey by the Scottish Book Trust.

2016 Hibernian FC wins the Scottish Cup Final, the first time since 1902.

2017 27 January T2 Trainspotting film released

Cables Wynd House (the Banana Flats), Leith, home of fictional Sick Boy, awarded Category A List status.934 deaths in Scotland caused directly by illegal drugs, opiates implicated in almost 90 per cent ; almost one-half aged over 35, thus from ‘the Trainspotting Generation’. This is the highest per capita figure in UK and Europe.

Almost 6,000 HIV+ people in Scotland, of whom 13 per cent are unaware; 368 new diagnoses in 2017; transmission by injecting around 14 per cent in 2017.

2018 Pennywell shopping centre, Muirhouse, demolished.

Introduction

…the greatest artists conjure an everywhere

out of a highly specific somewhere….

Howard Jacobson

SHORTLY AFTER MY arrival in Edinburgh in 1980 from my native rural Northumberland, I made half a dozen offers to buy a house for my family, and bought the first to be accepted. Enthusiastically I told my work colleagues we had somewhere to live. They were pleased for me. ‘Where?’ they asked. ‘Leith’. Middle class Edinburgh eyebrows went through the ceiling, incredulously, pityingly. They never went to Leith. They had their reasons, of course. To them, Leith was a decayed port town, always rough and tough, now reduced to a gap site. It was the best move I ever made, and I’m still here with no plans to move.

I worked as a social worker with a non-statutory agency, going from professors’ houses in the Grange to itinerant families in Muirhouse in the same afternoon. Briefly I was a part time lay chaplain in a prison, then a port chaplain in Leith, meeting seafarers on board ships. Imported Russian coal for nearby Cockenzie power station was stacked near the hoist that up to very recently had transferred local coal for export. This little cameo illustrates the collapse of Leith as the traditional port and working class town of which Irvine Welsh was writing. Now that the power station is demolished, both the hoist and the coal yard are unused and are surrounded by offshore vessels tied up during the slump in North Sea oil; a cameo that illustrates the further changes in Leith since Welsh’s book Trainspotting was published in 1993.

I have only a dim memory of Leith Central Station, so important in Welsh’s story. All I remember is the eastern gable end towering and glowering over the bottom of Easter Road. Talking it over with many others who lived in Leith during the 1980s, I realise that I am not alone in not registering the significance of this once mighty landmark edifice which had lost its power of attraction.

I was well aware, of course, of the arrival of HIV/AIDS, but, bringing up a young family and involved in neither the heroin scene nor the sex industry, it wasn’t very immediate. In 1987 we were astonished to have a letter from friends in England who had read the headline describing Edinburgh as ‘the AIDS capital of Europe’. Were we worried? our friends asked. Well, the plentiful junkies were very visible, and we knew all about the generalised anxiety and the apocalyptic warnings. Apart from our house being broken into a couple of times by junkies, like many of our neighbours, we didn’t know it was worse here than elsewhere.

For a period around the turn of the millennium I was trying to cut it as a tour guide. I couldn’t bear to be a kilted wonder on Edinburgh High Street. I needed a niche. My business name was Leith Walks. One day I had an email from a Dutch journalist. With a name like this, surely I did an Irvine Welsh tour of Leith? I didn’t, but I researched it and created one. The write up was good, and I had found my niche. The more I looked into Trainspotting the book and interpreted it for visitors, the more I realised how much Welsh had spliced geography and history into his fiction. Now I think of it as something like fictionalised journalism or a first draft of history, with satire, humour and social commentary thrown in; and in some respects it’s an autobiographical diary.

The publisher’s blurb on the first edition ran through the main issues: ‘…What with vampire ghost babies, exploding siblings, disastrous sexual encounters and the Hibs’ worst season ever… Trainspotting is a jarring, fragmented ride through the dark underbelly of Edinburgh, the festival city. There is not an advocate, a festival performer or a fur coat in sight as, with bitter passion and rancid humour, Welsh lays bare the lives of this ill-starred bunch of addicts, alcoholics and no-hopers. Written in the uncompromising language of the street, Trainspotting is […] stark, brave, and wholly original…’

And Jeff Torrington, on the front cover, writes: ‘… A wickedly witty, yet irredeemably sad book… takes us on a Hell tour of those psychic ghettoes which are the stamping grounds for junkies, boozers, no-hopers and losers…’

There is no mention of heroin, and only passing reference to addicts and junkies. Early reviewers also emphasised how the fiction is set within social malfunction, of which widespread, out-of-control drug (any drug) abuse is a symptom. Heroin and HIV/AIDS are certainly part of the story, but they don’t dominate in the way that later commentaries suggest.

Harry Gibson’s play was on the stage in the next year’s Glasgow Mayfest, and Danny Boyle’s film was premiered within two and a half years of the book arriving on the shelves. This astonishingly rapid expansion of Trainspotting as a brand can only be explained by the sheer vitality of Welsh’s writing and the topicality of the subject areas, together with the collaborative creative energy of Welsh, Gibson and Boyle. The play does without the redemptive ending, and in that sense is a more honest depiction of the junkie story. The film magnifies the redemptive ending into a much larger proportion of the film than it is in the book. Both the play and the film take the story away from Leith, and no harm is done to their basic premise: young man gets into heroin, experiences the highs and lows, has some laughs, sees the dangers, leaves it all behind. It’s a universal story.

Together these three art-forms carrying the same enigmatic, elusive title, different and inseparable became a commercial and cultural fireball and a byword for a savvy, insolent transgression, strongly associated with the Cool Britannia of the late 1990s. Together they played a considerable part in changing public discourse around heroin and junkies. Trainspotting is now a cultural reference point that combines heroin and social history which talks about ‘the Trainspotting generation’. And, with Welsh, Gibson and Boyle creating updates and sequels there is a Trainspotting cult of which Leith is HQ.

This book takes Welsh’s book Trainspotting, father of the whole thing, back to basics in 1980s Leith. It has grown out of my tours around town. Well-informed locals, tourists, aficionados and academics have fed and tested my knowledge and insights. While some of my sources are documentary, others are fresh Leith voices, with lived experience of their subject.

To ground the whole thing on location and in history, Section I opens up the enigma that was Leith Central Station, and three real-life contemporaries of Welsh tell of their encounters with heroin in Leith. Section II analyses the piecemeal composition of Trainspotting the book, working through inconsistencies and confusions and revealing clever structures and tensions. In Section IIITrainspotting’s principal characters guide us round the Leith of their day, putting their story into their context. Section IV gives a brief history of heroin and HIV/AIDS and an account of how they collided in Leith, and in Section V we go in search of literary bearings for Welsh’s Trainspotting. Sections VI and VII put the play and the film respectively into their contexts and get under their skins to see how they work.

Tim Bell

Leith, July 2018

SECTION I

By Leith Central Station They Sat Down and Wept

CHAPTER 1

Leith Central Station

YOU CAN GO to exactly the spot where the photographer stood to take the shot on the front cover of Leith Central Station and the Foot of Leith Walk. The horse-drawn tram dates it to no later than 1904, that is within a year of the opening of the station. You are standing in the heart of Leith and at the heart of Trainspotting. The Heart of Leith, the Foot of Leith Walk, and Leith Central Station all their have distinctive meanings but they can easily be pretty well synonymous.

Irvine Welsh uses this location to pin together his story Trainspotting. The small figure on the far pavement at the lower right edge of the shot stands at the taxi rank where Renton fulminates in the first episode: ‘Supposed to be a fuckin taxi rank. Nivir fuckin git one in the summer… Taxi drivers. Money-grabbin bastards…’ (p.4).1 Leith Central Station is the most emphatically identified location in the entire book. Directly opposite the taxi rank, out of sight up the opening at the end of the terrace beyond the third awning, Renton and Begbie go up the ramp that ran along the gable end into the derelict station at first floor level, for the ghostly figure to suggest that they are there to spot trains. One of the most moving tours I ever did was with a recovering alcoholic. On what remains of the ramp I talked him through the literary situation, and I had to leave him alone with his thoughts for quite a while as he looked across the street and considered the implications for himself of being brought back to where he began.

When I came to live in Leith in 1980 an old man told me that ‘the Fit ay the Walk’ was the heart of the town. There were no changes from this photograph then, but now you will see that the ridged glass roof to the left of the station clock tower and the railway bridge a few hundred yards up Leith Walk have been removed. I was puzzled. I found a dispiriting 1960s shopping centre called New Kirkgate behind and to the right of where the photographer in the 1900s stood, with an unprepossessing residentialised walkway on the other side of it, heading away to the north. I had seen the same many times before, in towns around Britain. There was endless traffic on the junction in front of me, and the station behind the faded facade under the clock tower that dominates the photograph was obviously derelict and useless. But with a little local knowledge and a longer view, I gradually discerned what the old man meant.

Kirkgate – that’s Church Street in modern English, and the name tells you the street has been there for many centuries – ran to the edge of the crowded medieval town at the 16th century defensive town wall at St Anthony’s Gate, which was over the right shoulder of the photographer. The broad boulevard in front of the camera was built as a military defence and line of communication in the 17th century Cromwellian war. When the army left, it became a fine high route to Edinburgh, provided they kept horses and carts off; hence the name Leith Walk. In the days before the tyrannical motorcar, this broad confluence was a natural focal point in the town. It was the start or end point for many a march and rally for well over a century. The centrality was already in the parlance: Central Hall was there before Central Station. In 1907 they deliberately placed the statue of Queen Victoria, which comes into Trainspotting, in the heart of the town; it’s just off the shot to the left. Now the Heart of Leith is reduced to this broad pavement where the camera stood, 30 yards by 50 yards, not much to call the heart of a town. It’s a favourite spot for canvassers. There’s some seating. It catches the best of any sunshine that’s going. There’s a municipal Christmas tree here every year.

Whether it was arranged or not, the potency of this image lies in the line of boys and men, all with their caps on, stretching from the heart of the throbbing old town, across this social arena and fulcrum of the town’s comings and goings, to Leith’s magnificent entry to the wider world. This brings us to Leith Central Station, so central to Trainspotting. To have a full appreciation of the metaphor Welsh works in lifting an obscure, enigmatic word from a page towards the back of the book onto its title page, we need an understanding of its massive, useless, elusive, vainglorious and dysfunctional purpose and presence at the heart of Leith.

*******

Leith Central Station was a bastard. In 1889 the North British Railway Co. (NBR), wishing to thwart rival Caledonian Railway Co.’s (CR) proposal to run a loop to Leith docks, and, having invested heavily in the new Forth Bridge and needing to increase its capacity through Princes Street gardens, undertook to build a dedicated passenger line and station in Leith in order to have its way on both counts. Corporate hubris and the absence of any strategic planning was one parent.

A single-track line with a ticket office and a shed on the platform would have been enough. The town had neither the density of population nor a sufficient hinterland, the nearby port notwithstanding, to justify one of the biggest stations in Scotland at almost three acres, and the largest to be built in Britain in the 20th century. Leith Burgh Council didn’t want a level crossing at Easter Road, so at vast expense the company built a bridge and brought the trains in at first floor level; hence the ramp at the Leith Walk end. The Council wanted a clock tower; the company provided the one we see today. The station had several sidings, four platforms, generously proportioned waiting rooms and a large concourse. No-one knows why they had the wonderful roof made by Sir William Arrol, who had the Forth Bridge, Tower Bridge, London, and North Bridge, Edinburgh, to his credit. He wasn’t cheap. The sheer size and extravagance of Leith Central Station is the unknown parent.

The people of Leith had no reason to concern themselves with any shortfalls of their glorious new access to the outside world. The enormous area, free of internal division and interruption of any sort, together with the great height of the roof which permitted excellent natural light throughout, created very special effects indeed. And the name: was it not something to be conjured with? Edinburgh and London didn’t have a Central station. Glasgow and New York both did. And Leith! An ordinary suburban station it could never be. This place was a cathedral of visions of distant places and triumphant homecomings, an emporium of travel.

Mr John Doig owned The Central Bar at numbers 7 and 9 Leith Walk, immediately to the left of the nearest awning in the photograph. There were two small lounges at the rear of the main bar, from which there was easy direct access up to the platforms. The interior was attended to in fine style and, for the price of a drink at the bar, you can still appreciate it, unaltered, in all its glory. Look at the paintings amongst the highly elaborate tiles, woodwork, plasterwork, coloured glass and mirrors: the Prince of Wales (shortly to be king) playing golf; yachting at Cowes Regatta; hunting with pointers; and hare coursing. Evidently Mr Doig was a royalist. The fabric is now protected, as is the whole frontage from the foot of Leith Walk round the corner into Duke Street, with the clock tower on the corner. Welsh often drank here, and it is the pub that best fits the description in ‘Courting Disaster’ as the location for the second après-court celebration from where Renton goes to Johnny Swan ‘for… ONE FUCKIN HIT tae get us ower this long hard day’ (p.177).

Not to be thwarted in the end, Caledonian Railway Co., within a few months of the opening of NBR’s Leith Central, opened its own line to the east docks by a circuitous route, crossing Leith Walk by the bridge a few hundred yards up Leith Walk in the distance in the Edwardian photograph. Leith Central Station became operational on 1 July 1903 with no formal opening. The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch sniffed that the huge station for a single train was like a two-storey kennel for a Skye terrier. The bread and butter business was the ‘penny hop’ to Edinburgh, but when the Leith and Edinburgh tram systems were unified in the early 1920s a big hole was knocked into the customer base. However, during the 1920s and 1930s, they ran a good service to Waverley and round the southern Edinburgh suburban line. And, as Renton correctly observes as he pisses in the dereliction half a century later: ‘Some size ay a station this wis. Git a train tae anywhere fae here, at one time, or so they sais…’ (p.308). The Leith Member of Parliament, George Mathers, would proudly board his train to London here; first stop Edinburgh Waverley. They ran football specials, beer safely on board, to Wembley, London, for international matches. And you could go to Glasgow in the west or Aberdeen or Inverness in the north.

But the services gradually declined. By the end of the 1930s the station not much more than half a mile away, the Caley at Lindsay Road, offered 37 daily trains to Edinburgh while there were only 27 from Leith Central. Many of the trains leaving the Central were single carriages behind the engine, widely known as The Ghost Train. One engine driver recalled Leith Central Station shortly before the war: ‘…this great edifice was like a sanctuary, a retreat from the hustle and bustle of places like Waverley Station. Sitting on my engine at Leith Central I have contemplated its spacious emptiness, not a soul in sight, only the quiet murmur of steam and warm fireglow…’2 Unglamourous and under-used, nevertheless interest and even fame came to it. It became a useful overnight shed for main line trains: enthusiasts – the trainspotters of their day – delighted in reporting that notable engines such as Cock o’ the North and Quicksilver were at times only yards away from unknowing shoppers and pedestrians in Leith Walk. Alan, an apprentice boy in a wood yard near Easter Road, often took a moment to admire Gresley’s Mallard as she glided past.

The concourse was spacious and empty enough to permit the Boys’ Brigade to hold their weekly drilling and parading practices there. It was much bigger than any church hall. The boys marched up the ramp off Leith Walk, and they had the place to themselves in the evenings. Sometimes there was a train at the platform, but there were no arrivals or departures, and no passengers. Lighting was not included in the permission, so sometimes it was pretty dark before they finished. For Nina, accustomed to overcrowded housing, all those toilets in the station were a thing of wonder. She didn’t have to ask if she could go! In the late 1940s Annie, living in Prince Regent Street, loved to go to the Cabin Café right on the corner under the clock tower, to meet her friends on Sunday evenings, where they would have juice and a cup of coffee. She was faintly aware that it was a railway station, but it never occurred to her to catch a train there. If she wanted a train, the Caley at Lindsay Road was far more convenient.

In 1947 the railways were nationalised, and British Rail (BR) acted on the commercial reality that its private enterprise forerunners had not, that this line and station were not viable. On Saturday 5 April 1952, the last passenger train pulled out of Leith Central Station. In the local press there was no advance notice given on the day before or on the day itself, and there was no report or comment the following Monday. Only a local photographer turned up to record the occasion. From this point Leith Central Station faded even further from collective awareness in Leith.

After a decade or so of standing empty, it became useful again in an unexpected way. In the 1960s steam gave way to diesel. BR found itself having to maintain both steam and diesel engines for several years during the changeover, and adopted Leith Central as a maintenance depot for the new diesels while the sheds at Haymarket continued to service the steam engines and were adapted for diesel. It was known to BR as Depot 64H. It was used as Scotland’s first diesel driving training school. All this went on entirely within the building, behind closed doors, as it were, and without any great comings and goings from the surrounding streets. When BR had got rid of steam engines and adapted the Haymarket sheds, in 1972 Depot 64H was surplus to requirements.

Up to now the line had remained open as far as the Hibernian FC Easter Road stadium for occasional football specials. But now the line was closed completely. Just as lighter, cleaner, reversible diesel engines had been tested and were readily available, the Conservative governments of the 1960s, with their ideological objection to nationalised industries, had taken an axe to branch lines throughout the country. Any remaining chance of Leith Central enjoying a revival died.

Apathy and neglect set in. Anywhere else in the country such a large prime site in the centre of a town would have been a target for developers. In Leith there was no such pressure, and no options or plans were discussed. Leith Central Station, in all its magnificence, became an icon of economic downturn, high unemployment and, with the demolition of streets all around it, the Leith diaspora.

A flat local economy and high unemployment took hold. Councillor Alex Burton’s pleas to do something constructive with the station fell on deaf ears. BR let out some office space as a Job Centre at the top of the staircase from the Leith Walk / Duke Street corner. The alterations were carelessly done. The new false ceiling masked the access hatch to the clock tower. The usual contractor turned up to restore the clock to GMT in October 1978 but couldn’t gain access. They had to fish out the building’s drawings and the job was done in December. The main entrance to the station remained bricked up from an earlier closure, and access to the Job Centre was moved to a smaller doorway a few yards down Duke Street. An opening that was intended for purposeful comings and goings was taken up by people hanging around, the way they do when they have nothing to do and nowhere to go. br’s commitment to redevelop the station area for warehousing and, ultimately, offices never materialised.

Meantime, the platforms and sidings, under their vast roof, fell into disrepair. For anyone looking for a hidden place for sex, drinking, fighting, drug-taking, sleeping rough, or an open toilet, it was perfect. There was plenty of room for all, and no need for private parties to intrude on each other. Access was easy. Inside there was a creepy air of the Mary Celeste. The platforms were intact, with the railings at their ends helpfully there to prevent anyone falling in front of a train. The cubicle-like café and bar were there, the ticket booths could be broken into, the toilets stood with the doors hanging off and no plumbing.

The kids found it a wonderland. It became a rite of passage to go into the station, and some kudos was attached to bringing an air rifle with which to shoot the plentiful pigeons. And best of all, there was a ghost. It was legless, so it bounced or floated two or three feet over the ground. It wore a Celtic FC top so, naturally, it had big red eyes and horns. In its previous life it came to a game at Easter Road but its legs were crushed by a train. Some daring youngsters got onto the top of the roof, and the neighbours watched in horror. There were plenty of entrance points, the easiest being at the top of the ramp off Leith Walk, where there was no serious attempt at security.

Nothing happened. Eventually the Council acquired the site. Various plans were drawn up. It was big enough for a small sports stadium, whether covered or open. There could be a five-a-side football pitch behind the Leith Walk frontage, next to tennis courts, and a running track in the area where the sidings had been. The ramp from Leith Walk would lead nicely into the upper level of the complex. This 1980 proposal came to nothing. The feisty Revd Councillor Mrs Elizabeth Wardlaw deplored the Council’s ‘lack of foresight and determination to find funds and expertise… for the social, commercial and recreational development [of Leith Central Station] not only for… Leith, but the whole city of Edinburgh.’ She rejected a fellow councillor’s description of it as a Dickensian dump; she called for the potential of its ‘vast unobstructed area and massive walls to be imaginatively developed’.3

Frank Dunlop, the energetic and high profile Director of the Edinburgh International Festival came to see it. Various people proclaimed its excellent potential as a transport museum, an exhibition centre, or a concert venue and arts complex. You could have a Guggenheim there. In late 1988 it was decided. The roof and the platform level would be removed and the southern perimeter walls reduced. There would be a municipal Waterworld in place of the concourse area, and a Scotmid superstore in place of the platforms. The sidings would become a car park. Annie, who had left Leith and brought up a family in Edinburgh, was astonished to be told it was going to be demolished; she hadn’t realised it was still standing.

Welsh pitched his episode ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’ in the few weeks between the decision and arrival of the demolition squads: ‘… the auld Central Station… now a barren, desolate hangar, soon to be… replaced by a swimming centre’ (p.308).

Precisely a century after Caledonian Railway Company gave notice of its wish to run a passenger line to Leith, Leith Central Station was demolished. The contractor placed an ad in The Scotsman in February 1989:

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

You can buy a part of Edinburgh Heritage…

dressed stone for sale…

Sandy Mullay was invited to write an obituary in the Edinburgh Evening News. He couldn’t resist the last line: ‘The station now departing was one nobody wanted…’4 A bastard to the end!

*******

If you call yourself a creative writer you should be able to work something up from this metaphor-rich location. The episode ‘Trainspotting at Leith Central Station’ was published as a freestanding short story before it was given its place in Trainspotting. Welsh asked a friend, Dave Todd, to create an image of the vision and theme of the piece; the result was a train full of partying yuppies passing through a derelict Leith Central Station that is full of skeletons – a ghost train in reverse, Edinburgh’s prosperity mocking Leith’s austerity. Who were the skeletons? The crowds that never came to this vast place and who never will? Leithers? Leithers now in Edinburgh, Muirhouse, South Africa, Australia, Canada? Who is spotting whom? In an interview with The Big Issue in 1993, in which the image appeared, Welsh explained: ‘I wanted to do a book about Edinburgh and attack the perception of it as this bourgeois city where everything cultural happens, a playground for the Guardian/Hampstead middle classes. There’s another reality that runs parallel with that…’5 He has also said that he was writing in a working class voice that happened to have a Leith accent. In a strong way, Trainspotting is a Leith/Edinburgh story. Todd’s image was intended by Welsh and Todd to be used on the front cover of Trainspotting, but the publisher commissioned the photograph of the two figures with grinning skull masks in front of some trains and the departures board at Waverley station that became so familiar.

Renton’s journey from Waverley station in the eponymous episode is the most focussed geographical journey in the whole book. Every step can be retraced, and details along the way can be observed and considered, much like Stephen Dedalus’ journey in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Welsh has brought his characters to Leith Central Station, on foot, for the journey and the location itself to speak loud and clear.

Coming home from London for Christmas, Renton leaves Waverley station by the Calton Road exit, as many Leithers do who are pleased to stretch their legs after a long train journey. He walks confidently past other people’s problems up to Leith Street and down towards the Playhouse, with the surrounding restaurants. It is indeed ‘downhill all the way’, in common parlance a cheerful, well-worn double entendre meaning either that things can only get easier or that things will only get worse. But there’s nothing casual about it. Look for a bit more bite. As we shall see, in Welsh’s late 1980s Edinburgh’s rubbish flows downstream to Leith, Leith disposes of Edinburgh’s sewage, Leith takes Edinburgh’s junkies and the sex trade, Leith is demolished while Edinburgh stands tall, Leith weathers economic storms while Edinburgh preens itself as a city of culture, protected by the castle walls of privileged status. In the fiction, at the top of Leith Walk ‘middle class cunts’ in Edinburgh have an evening’s entertainment at the Playhouse and table reservations at nearby restaurants, while at the Foot of the Walk Begbie and Renton piss in their own situation in derelict ruins in the dark. It’s downhill to Leith, alright.

The timing of the setting of the episode is historically precise: it is Christmas 1988. Instead of something special, there would be a supermarket. Supermarkets are all the same. This one would do for the Junction Street shops what the managed Kirkgate shopping centre did for the shops along the old Kirkgate. Even though this was going to be a Co-op (and Leith was a Co-op town), it would sweep away locally owned businesses and destroy the micro economy and diversity of interest in the area. As for the swimming centre, there was already a perfectly good pool a few hundred yards away in Junction Place. Welsh seems to sense, correctly, as many people did, that it was a vanity project (although it was popular, the pools leaked, it was massively energy-inefficient, it was unsustainably labour intensive through poor design, and it lasted a mere twenty years; the pool in Junction Place is still going well). Now it had come to this, the final insult. This was the last surgical knife in the almost moribund body of Leith as it was being laid out to become north Edinburgh’s ghetto or, worse still, a suburb of Edinburgh.

While they are pissing the conversation is of distant collective memories and of what is being lost. We seem to have already met Begbie’s father in ‘There is a Light That Never Goes Out’ and it’s no real surprise that it turns out he is the ‘auld drunkard’ who approaches them. Is he the ghost of a generation of unemployed Leith men? Is he the ghost of the Leith diaspora? Is he the ghost of a man who has thrown his life away to alcohol? Maybe all three. Begbie is a child of all this. Violence, alcohol abuse and general depravity are strongly linked to persistent social instability and poverty. Merely to observe that the Begbies, father and son, are morally reprehensible is missing the point; they are used here as representative victims of the retreat of the economic tide and failed public policies.

Renton, who starts out from Waverley station in Edinburgh as a reasonably confident young man, and despite his feeling that he is safer because he is coming ‘hame’, deteriorates to a ‘pathetic arsehole’ in Leith’s pervasive bad atmosphere. It is tempting to think of the character Second Prize as a metaphor for Leith. His nickname is explained in ‘Station to Station’ and it seems unlikely that it was contrived for the purposes of this metaphor, but both the name and his condition work towards it. Renton tries to help him, but it’s ‘useless’. The last person we meet is the unnamed guy in Duke Street who is meekly resigned to ill treatment; is he too a representation of Leith? And is Begbie’s malign belligerence and indifference to others no more than a personification of everything that had gone wrong in Leith, to the permanent damage of the community and real people within it? Things are not well in Leith.

CHAPTER 2

Leith Junkies

LET’S RE-IMAGINE the Edwardian photograph. Now we see a line of 1980s Leith junkies, stretched out between home and the doorway to faraway places where problems are left behind. Their access, whether the station or heroin, is there, just a step over the road, a presence that’s impossible to miss, with easy access despite the closed doors, and a dark, dirty and disordered interior, deplored by most people. Home for them is neither secure nor satisfying; demolitions and dispersals characterise their environment, and few have had the opportunity to embark on rewarding and purposeful careers. They have been brought up hearing Mrs Thatcher’s rhetoric on the right to choose, that everyone has consumer options – not that they have had many. The skeletons in Leith Central Station in Dave Todd’s image are now junkies, dead or alive, and HIV+ people, dead or alive.

Within the eponymous episode Renton’s journey to Leith Central Station is just as much a review of his encounter with heroin as a return to Leith. He notes passing his old gaff in Montgomery Street, he nods at Albert Street, not mentioned elsewhere in the book but well known locally as Dealers’ Alley back in his junkie days. Begbie’s company in Tommy Younger’s explicitly invites a review of Renton’s career in junk since the suppository scene in ‘The First Day of the Edinburgh Festival’ gave him a good opportunity to quit. Begbie seems to know what happened way back in ‘Cock Problems’ – Renton gave Tommy his first shot. And going up the ramp to the terminal station brings Renton directly across Leith Walk from the first location to be identified, back to where he started, the taxi rank where on the second page of the book he and Sick Boy fume about taxi drivers who are unaware of and unresponsive to their junkie needs.

It is ‘the festive season’, the end of the year, a punctuation point in everyone’s life, when we review the past and look forward to the year ahead. Intimations of mortality need not be morbid, but, for a young man, Renton is well acquainted with death. He is the only survivor of the three boys in his family. Wee baby Dawn died, and the last we heard of her mother, Lesley, she was in intensive care in a Glasgow hospital following a suicide attempt. Dennis Ross didn’t make it. Renton has just been to Matty’s funeral, and Tommy is in trouble. He knows it is Leith Central Station’s last Christmas – could it be his too?

Begbie’s reference to Tommy in the pub links this episode to ‘Winter in West Granton’ not only in the storyline but also thematically. There is no mention of the season in which the episode is set; it’s a spiritual winter. West Granton Crescent too was a massively oversized, dysfunctional, dead end place and full of metaphorical skeletons. It should never have been built, and it was due for demolition (it was demolished about 20 years later). This stretches the junkie implications across the two episodes. When Renton is with Tommy he appreciates the reducing likelihood of successfully quitting with each failed attempt. If Renton doesn’t get out of Leith Central Station quickly the whole edifice will be brought down on top of him. He, like it, will have all his unrealised potential ingloriously and unceremoniously ended. Many people will be pleased to see the almost invisible derelict trouble spot go. Renton is uncomfortably close to being viewed in the same light, his existence barely noticed, his departure unlamented, a forgotten piece of history, at best a statistic. He, like the station, will be remembered, if remembered at all, as a bringer of danger and squalor, a waster and a loser.

To adapt Psalm 103 verses 15, 16 ‘As for [a junkie], his days are like [Leith Central Station]; he flourishes like a flower of the field; for the wind passes over it, and it is gone, and its place knows it no more.’

*******

Just as we can imagine that some of the men in the Edwardian photograph died in the First World War, so some of the 1980s junkies died, whether by overdose or with HIV/AIDS or some associated complication. However, Fred, Audrey and Donnie, who are all within a very few years contemporaries of Welsh, knew the Foot of Leith Walk in their junkie days and survived at least 20 years, have agreed to let me recount their stories. Their names are changed.

Fred’s story

Fred doesn’t like coming to Leith these days. He could see someone who might offer him something he would have to refuse. He lives in Edinburgh city centre.

Fred knows exactly when and where he acquired HIV. In London, in 1983, he shot up – only three or four times, he says – with a couple of older hippies who had a baby. They would fill up the syringe and share it. To check the needle was in a vein, they pulled into the chamber a little blood which, of course, was transferred to the next one. They were not remotely aware of any potential danger. This was the only time he injected. He left London and took to chasing the dragon. A few years later he had a phone call from London – he should get himself checked because one of his London friends had become HIV+. But by then he had already been diagnosed positive. He has been to many funerals over the years where he has strongly sensed other people feeling: ‘this should be for you, Fred’. Now, well after a Thirty Years Later party, he has developed a talent for photography, a hobby he pursues in many different countries.

He didn’t like growing up in Pilton. He had a poor attendance record at Ainslie Park School (Welsh attended there, about five years ahead of Fred) and was sent to the residential Dr Guthrie’s List D school in the south of Edinburgh. There were lots of bored boys there, and he had his first experiment with drugs with them – glue-sniffing. He was sent to a more disciplinarian establishment in Ayrshire, to which he responded quite well. Home again at the age of 16 he got a job with one of the last of St Cuthbert’s horse-drawn milk carts in Stockbridge, where he became aware of the drug-taking hippie community centred round The Antiquary pub on St Stephen Street, known to everyone as ‘The Auntie Mary’. Back on the schemes he saw his own age group getting into drug-taking and stealing and he made a deliberate attempt to get away from it all. He was rejected at the Army recruitment centre because of his police record; on overhearing his mother say he would try to join the American army, the recruiting sergeant advised them to go somewhere they knew people and get someone to confirm that they had known him for two years. He joined the army from Manchester, where his uncle’s neighbours obliged. In nine months he went from being a Sid Vicious lookalike, with red-tipped points in his spiked hair, to standing to attention in a bearskin.

Then at the age of 19, he was posted to the Falklands for active combat duty. Nothing had prepared him for brushing this close to death. He saw what bullets could do to a body. He thought hand-to-hand fighting was a thing of the past, but he was ordered to fix his bayonet, with which he killed an Argentinean who was manning a machine gun. He cleared the dead, friend and foe, from battlefields. The bodies froze quickly in the cold. He found some hash in the pockets of a dead Argentinean. He smoked it in a trench with a ringside view of the aerial attack on Mount Longdon: stoned, ‘it was the best show I ever saw’. Guarding captured Argentineans, he fell into conversation with one of them. Recollecting the conversation later, he came to the conclusion that he was fighting a politicians’ war: Thatcher, with unemployment problems and Galtieri with problems of too many people disappearing, both found the theatre a welcome distraction. His only consolation now is that he played a part in toppling Galtieri. Shortly after this his leg was broken as his unit came under an infantry mortar attack.

Looking back on it, being sent to the hospital ship was the defining turning point of his life. He recalls the moment when he had a tap on his waistband. Looking down he saw a double amputee, and this was the moment he first thought about his future after the war. Although not badly injured himself, someone told him to call out for Omnopon, an easy-to-issue opiate painkiller. The nurses and medics were not set up to deal with needy, manipulative, deceitful patients. He acquired a habit in the six weeks on board before the ship berthed at Montevideo and he was flown home. There were excellent facilities at Woolwich Hospital for alcoholism, and none at all for drug addiction. It was on several day leaves from the hospital that he acquired HIV, shooting up with the hippies. He told the padré that he had a problem with drugs, and shortly afterwards he was asked if he wanted to leave the army. Without being given time to consider his options or take advice, he left, signing away his pension rights and such treatment as may have been on offer for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He heard later that three of his mates hanged themselves, presumably unable to handle the effects the war had on them.

Fred went to Liverpool, to be with the girl he had had a child with before the war. Living with her, their son, and her parents, he couldn’t settle and he caused problems. Quite rightly, he says, he was put out. He was homeless for around a year – not so difficult for an ex-soldier. One day he stole the Liverpool Lord Mayor’s chair from the city chambers. As he was lugging it out of the door onto the street the security guard challenged him. ‘I’m taking it for repairs’ he said. The security guard asked him to tell his boss to give him more information. The next day’s Liverpool Echo reported that an Irishman had stolen the chair. Fred bought a few grams of heroin with the proceeds. The chair was recovered, unharmed, a little later. He was sent down for 18 months in Walton prison for burgling a solicitor’s office. In the safe they found some photographs of a swingers’ party, and his mates wanted to try a bit of blackmail, but Fred was only in it for easy money. At the court appearance he looked for help from the army – in the event the officer expressed the view that he had let down the regiment. He remembers sitting in a cell in Walton prison with two others, reading in a newspaper that one in three people with what it called the new ‘Gay Plague’ would die within a year. One of the others in that cell died of AIDS in 2010.

He was discharged to Edinburgh, where he saw the drug scene had changed from being reasonably relaxed and friendly to becoming violent and dangerous. He knew people – for legal reasons, he refuses to discuss whether he was one of them – who went to Glasgow to pick up consignments of heroin, running the risk of being charged with dealing if caught, and attracting a sentence of seven or eight years in prison. Telling the police who he was running for would attract a different sort of punishment. He used to buy his own stuff at The Gang Hut, which he remembers as somewhere near Albert Street. It had a heavily reinforced door – you knocked and asked through the letterbox ‘anything happening?’ Money went in first, then out came the wrap of heroin. Secondary dealing was done in nearby pubs – Fred remembers The Central Bar at the Foot of Leith Walk – by people who weren’t set up with the security of a flat. He sold on one of his own purchases, spinning it out with some contaminants (cutting it), which he regretted, and he says he didn’t repeat it. Later he got to know the people in The Gang Hut, and spent days in there, with everybody briefed on how to flush incriminating items down the toilet in the event of a police bust.

Diagnosed HIV+ by now, Fred wasn’t expecting to live more than a year. His biggest fear was contracting Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer causing foul black lesions on the skin. But he was persuaded to be positive about his condition, and he says he was the first heterosexual to join a self-help group for what was then known as GRIDS