26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Choreography is the highly creative process of interpreting and coordinating movement, music and space in performance. By tracing different facets of development and exploring the essential artistic and practical skills of the choreographer, this book offers unique insights for apprentice dance makers. With key concepts and ideas expressed through an accessible writing style, the creative tasks and frameworks offered will develop new curiosity, understanding, skill and confidence. The chapters cover the key areas of engagement including what is a choreographer?; getting started; improvisation and ideas; context, stage geometry and atmosphere; movement as dance in time and space; solo, duet, trio and group choreography and finally, structure and the 'choreographic eye'. This is an ideal companion for dancers and dance students wanting to express their ideas through choreography and develop their skills to effectively articulate them in performance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 221

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

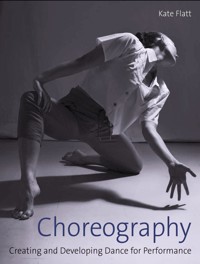

Choreography

Choreography

Creating and Developing Dancefor Performance

Kate Flatt

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

© Kate Flatt 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 612 8

Frontispiece: Afterlight. Choreography by Russell Maliphant. Dancer Daniel Proietto. HUGO GLENDINNING

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. What is a Choreographer?

2. Getting Started: Essentials of Choreography

3. Movement in Time and Space

4. Context, Stage Geometry and Atmosphere

5. Choosing and Working with Music

6. Solo, Duet, Trio and Group Choreography

7. Structure and the Choreographer’s Eye

Conclusion

Glossary

Appendix I – Music Genres

Appendix II – Searching for Music for Choreography

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

This book has been written from my perspective as a choreographer and offers insights gained through professional practice as well as from remarkable teachers.

In my work as a choreography teacher and mentor, I have spent several decades in studios sharing the joys and struggles that young and apprentice choreographers encounter. I have also learnt a great deal from them and appreciate the memorable moments they have created in the studio. Their discoveries have taught me a lot about the framing of tasks and observation exercises given in the book, which introduce and develop key understandings.

Apprentice creators have also enlightened me about what is possible to grasp at the outset of the choreographic process in terms of starting points and what can only be acquired gradually through creative encounters with dancers in the studio.

Marie Chabert and Amir Giles in rehearsal.CHRIS NASH

CHOREOGRAPHIC PROCESS

The chapters in the book introduce the process of choreography as studio development from initial starting points, through the making of a work as a complete choreographic statement.

It addresses practical considerations on choosing dancers, working in the studio and with music, and offers tasks for improvisation and creation. The final chapter addresses finishing the work in the studio and transferring work to the stage, with advice on lighting, costume and giving a title to a piece of choreography. The more complex processes of visual presentation involving collaboration with designers, lighting designers, composers and other specialist theatre artists are referred to, but these are in reality the subject of another book.

NAVIGATION

The book is not designed as a manual of ‘how to’, but as an aid to navigation through the choreographic process. It introduces key elements, strategies, components and tools required along the way. The apprentice choreographer is encouraged to develop both art and craft, through personal intuitive engagement and by developing an ‘eye’ through observation of what emerges. Along with that, there is an emphasis on how choreographers develop by staying in touch with the feelings and passions that are integral to the realization of ideas as choreography.

CHOREOGRAPHY IN EDUCATION

The teaching and learning of choreography are an important part of dance training. Written with artistic development in mind, the aim of this book goes beyond the need for the student in dance education to fulfil GCSE and A level examination criteria. The use of terminology is related to the range of terms used in professional practice and may differ from standard educational terms derived from Laban’s dance education principles. A Glossary is provided to expand and unpack the different concepts addressed by the different chapters and tasks.

Dancers in rehearsal.MATTHEW BALL

Examples of works by established professional choreographers are referred to and can be researched online by the reader. As a field of study, choreography is rich in transferable skills that are valuable for all. These capacities reach beyond the studio and are relevant for all aspects of life: flexibility; negotiation; creative thinking; collaboration; composure; leadership; communication; and critical engagement.

CREATIVE TASKS

The chapters contain tasks and observation exercises designed around the various concepts that are introduced and are described for the reader to try out as experiments in studio practice. For example, dance movement, as the medium of choreography, can be explored in the studio through suggested tasks to experience the shaping of movement in space and time. They have been devised to inspire and develop knowledge and skills for those new to choreography and the processes of articulating ideas as dance. The tasks have also been tested at different levels of study over several years: in school situations; at undergraduate and postgraduate level; and in professional situations. Some have been developed from creative exploration in my own choreography. As I am not in the studio and able to demonstrate or answer any questions they might raise, they have been a challenge to describe clearly and succinctly!

By using imagination and problem-solving skills, the reader will be able to interpret the tasks in their own way. There is not a right and wrong attached to them. However, I wish I could be there to see the solutions found.

DEVELOPING THE EYE

Choreographers in the process of making a complete piece of work, develop a discerning, objective eye. This capacity means being able to stand back and look at what has been created, and at how ideas and material communicate from the point of view of the audience. The final chapter addresses the objectivity required of the apprentice choreographer in standing back from the creation process on completion of a work for a final studio showing.

MUSIC

Appendix I identifies a range of music genres and composers suggested for readers, in addition to Chapter 5 on ‘Choosing and Working with Music’. In the bewildering world of easily accessible music on the Internet, choosing music can be an overwhelming experience with too much choice being on offer. The chapter has examples of music choices by established choreographers, which can be referenced through online searches or company websites.

Ultimately, this book is designed to inspire and to give strategies to support the development of choreographic ideas that won’t go away. It reaches out to apprentice choreographers who feel compelled to realize their own dance works and pursue a career in dance.

THE DEVELOPING ARTIST

Rainer Maria Rilke, writer and poet, says more beautifully than I can what is required to maintain composure and sense of oneself as a developing artist:

Go through your development quietly and seriously; you cannot disrupt it more than by looking outwards and expecting answers from without to questions that only your innermost instincts in your quietest moments will perhaps be able to answer…

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (1929), translated by Charlie Louth (Penguin edition).

CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS A CHOREOGRAPHER?

THE CHOREOGRAPHER AS A PRACTITIONER

The choreographer as a practitioner is considered to be a creative artist equal to a composer of music, an author of a book and a film director. A thumbnail history of the choreographer’s emergence through history and how the role has changed and developed can be traced from dances in the village square, via the royal courts and into the range of contexts and theatres of today.

Noémie Larcheveque playing with shadow.JACK THOMSON

Dance without choreographers

Traditional dance forms from all over the world do not involve a choreographer as we know it. Social and ritual dances formed of circles, spirals and patterns emerged, apparently with no need of someone to decide what or how people should dance. Solo performers in diverse forms have evolved their own dances, recognizable as coming from a specific tradition or style. These universal expressions of dance occur as a spontaneous ritual or celebration with live music, often with traditions handed down through centuries, in urban or village settings. Similarly, in dance halls, social dance has developed without choreographers, by imitation and with semi-improvised elements as found in jive, samba, tango, jigs and street dance. Diverse traditional dance forms are available widely to view as video clips on social media and highlight the global riches of dance without choreographers. Dance traditions have been documented and researched by ethnog-raphers, as a record of how people danced in earlier times and in different parts of the world.

The dancing master

In the Renaissance, dance tutors emerged as experts and taught people in the royal courts of Europe to excel in the dances such as the pavane, galliard, la volta, minuet or sarabande. Elizabeth I was famous for her love of dancing and before breakfast would dance a galliard, a man’s jumping dance. Perhaps this was her way to keep fit? Her ministers attended her licensed dance academies, learning from Italian dancing masters, hoping to gain promotion by impressing the queen at the court ball. By the seventeenth century, in the reign of Louis XIV of France, dance had grown in prestige and importance. Dancing masters arranged dance events as court spectacle, whilst meticulously recording the dances and the corresponding court rules of etiquette.

The ballet master

In the nineteenth century, ballet masters developed ballet training to higher levels of technical accomplishment. There are many images captured by the painter Edgar Degas of tutu-clad young women being taught by an older man – the ballet master and guardian of ballet tradition. In the development of Western theatre dance, ballet was performed to instrumental passages as interludes in operas. It then grew into a respected art form handed down as the nineteenth-century story ballets of the Romantic era and later on the iconic classical Russian ballets of Swan Lake, The Nutcracker and The Sleeping Beauty.

Brazilian folk ritual of Bumba meu Boi, with dancer Carolina Paulino.SHEILA BURNETT

Queen Elizabeth I dancing at court.

Painting by Edgar Degas of a nineteenth-century ballet master in rehearsal.

The choreographer

In the early twentieth century, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev created the Ballets Russes, basing the company in France. As a producer, he pioneered rich and ground-breaking productions combining dance, music and art. He enabled radical new creations, making ballet an avant-garde art form. He promoted his choreographers as lead artists, who collaborated closely with composers, artists, designers and performers. Among them, Fokine, Nijinsky, Massine, Balanchine and Nijinska would go on to work with artists such as Bakst, Matisse, Picasso, Derain and Dali as stage designers. Meanwhile, composers such as Stravinsky, Debussy, Prokoviev and Ravel collaborated in developing innovative new work with these pioneering choreographers.

Modernism and the choreographer

In the early twentieth century in America, in keeping with modern art, drama and music, Martha Graham pioneered a shift in emphasis away from entertainment and spectacle, towards inner, psychological motivation. Her work showed how emotion could be embodied in the movement. Along with Doris Humphrey, Graham had a profound influence on Alvin Ailey, José Limon, Pearl Lang, Katherine Dunham and Glen Tetley in the USA. One of her dancers, Robert Cohan, moved to the UK to develop his work there during the 1970s and 1980s.

Meanwhile, in Europe, choreographers of the Modernist movement, Mary Wigman, and Kurt Jooss, were to influence the work of late twentieth-century choreographer Pina Bausch. She, in turn, has had a profound influence on present-day choreographers, whose innovative work in dance and theatre is seen across Europe and America.

Choreographers and changing the space

In the mid-twentieth century, the stage space came also to be seen as an abstract canvas. Pioneering choreographer Merce Cunningham moved away from representation and narrative within choreography. Alongside innovative artists such as John Cage, Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, Cunningham is credited with breaking down the hierarchy of the stage space. He asserted that dance movement did not have to represent anything and also that no single place on the stage is more important than any other. He also pioneered thinking on the important interrelationship of space and time in choreography and introduced the strategy of chance operations. His innovations included site-specific works, use of interior and exterior locations, working with film and other new technologies. He has had a profound influence on succeeding generations of choreographers. The training technique he developed continues to be taught in dance schools around the world.

Choreographers in the twentieth century

In the dynamic cultural melting pot of post-war New York, George Balanchine continued to move ballet forward. He created spatial and musical ‘arguments’ with his ballet dancers, shaping compelling action in his abstract works like Agon (1957). He developed highly articulate use of stage geometry with a centre stage focus and established what became known as his ‘neo-classical’ signature.

In Britain, Ninette de Valois founded the Royal Ballet, bringing the great classical story ballets of Imperial Russia to Britain. De Valois oversaw the development of a choreographic heritage with narrative works by Frederick Ashton, John Cranko and Kenneth Macmillan. This has influenced the development of recent ballet choreographers such as Liam Scarlett, Cathy Marston and Christopher Wheeldon.

Musical theatre choreographers

In the world of musical theatre, choreographers working in collaboration with producers, writers and directors became vitally important contributors to the commercially funded musical theatre of the post-war era. Jack Cole, Agnes de Mille, Bob Fosse, Jerome Robbins and Susan Stroman, amongst others, became pioneers in musicals of the latter part of the twentieth century. They used jazz, ballet, traditional and modern dance to create a deep connection to the story being told, instead of the dance being merely spectacle or ornamentation. Musical theatre productions from both New York and London have enjoyed big commercial gains and global success for its choreographers.

Late twentieth-century radicals

In the late 1960s, a group of interdisciplinary performers, artists and makers emerged in New York. Choreographers Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, Douglas Dunn and Steve Paxton, associated with the ‘Judson Church’ group, questioned the validity of many former principles of dance making. Their performances would involve improvisation, with the dancer in a constant state of exploration rather than delivering shaped choreography. New work was created in spaces not designed for performance – lofts, streets and rooftop locations became the performance environment. Postmodern innovations have also brought greater democracy to choreographic practice, with creative strategies that have enabled dance to become more inclusive for non-professional and differently abled performers.

‘The Bottle Dance’ from Fiddler on the Roof. Directed by Lindsay Posner. Original choreography by Jerome Robbins with additional choreography by the author.SHEFFIELD CRUCIBLE PRODUCTION (2006)

Revival of Trisha Brown’s Roof Piece (1976), in New York.LAUREL JENKINS

Group in workshop for MA Movement Direction, RCSSD, London.LUDOVIC DES COGNETS

Movement directors

The work of a choreographer in plays and opera encompasses that of a movement director. There is an important distinction between the work of the movement director as a creative artist in text-based theatre or opera and that of a choreographer. Similar strategies and approaches may be used by both practitioners in the studio, but to different purposes in the outcomes of their work. A movement director works with the skills of actors and singers to shape their physicality and body language, which may emerge as a kind of ‘invisible choreography’ embedded in the action. Their work serves the narrative and also heightens the intensity or emotional impact of dramatic action.

Choreographers in companies in the UK

In the 1970s, the Rambert Dance Company built on the pioneering approach of Marie Rambert in supporting new choreography by Glen Tetley, Norman Morrice and Christopher Bruce. Under the leadership of Robert Cohan, London Contemporary Dance Theatre promoted and toured the work of Siobhan Davies, Micha Bergese, Robert North and Darshan Singh Bhuller. In the 1980s, independent choreographers emerged and a national touring infrastructure for smaller-scale choreographer-led companies was set up. With this came a priority to make dance more widely accessible through participation, training and education programmes.

Suzan Opperman and James Stephens in rehearsal.MATTHEW BALL

Finding ideas in the studio. Dancer Maud-Helène Treille.MATTHEW BALL

CHOREOGRAPHERS TODAY

Art and craft

The choreographer is a creative artist who captures the essence of an idea in dance. Their craft is the ability to create distinct, sole-authored works that can be abstract, thematic, or narrative.

Being a choreographer involves developing the ability to:

•invent and devise dance movement using imagination, perception and feeling

•shape dance movement in space in time

•create stage pictures and non-verbal images

•develop a range of strategies to solve problems in the abstract

•use dance to suggest things that words cannot.

Being a choreographer involves developing inter-personal skills in order to:

•work with people using flexibility and negotiation

•maintain composure and good judgment in leadership with others

•manage time when working towards completion for a deadline

•communicate, collaborate and use critical engagement.

Growth and change

The choreographers of today create new work with dancers who are trained in a range of dance disciplines and whose abilities contribute to dance as a dynamic force in the twenty-first century. Funding and support for new choreography in the UK embrace a rich and diverse art form, for ever-growing audiences. Working as a choreographer also includes community work, designed to make dance accessible to all through participation and educational work. These developments offer career possibilities and challenges for innovation by choreographers in all genres of dance.

A linked chain dance – one of the oldest dance forms. The Ballroom of Joys and Sorrows (2012).CHRIS NASH

Choreography devised with participating dancers. The Ballroom of Joys and Sorrows (2012).CHRIS NASH

Dancers using trapeze in Melt (2016) by Sharon Watson with Sandrine Monin and Sam Veherlehto.JOE ARMITAGE

What styles of dance?

Boundaries in terms of style have become blurred. The dance world does not any longer divide neatly into clearly labelled styles. Choreographic languages draw on a wide range of dance forms from across the globe and often show a fusion of styles in new work. Choreographers of today create for an industry that is notable for its innovation, inclusivity and acceptance of differently abled bodies.

Here are examples that give insight into the broad range of styles across all dance forms:

•Crystal Pite, William Forsythe and Alexander Ekman make work that broadens the idea of what ballet can be, sometimes completely reinventing it.

•Candoco and Stop Gap are UK companies whose inclusive contemporary dance work involves choreography for mixed ability dancers with wheelchairs.

•Wayne McGregor makes work that engages with technology, powerful visuals and scientific advances for his own company and international ballet companies.

•new work, drawing on African heritage, has a significant and growing profile in the UK, with global connections supported by the organization Dance of the African Diaspora.

•contemporary choreographers Kim Brandstrup, Aletta Collins, Akram Khan, Wayne McGregor and Hofesh Schechter have all been commissioned to make new work for ballet companies around the world.

•Shobana Jeyasingh, Akram Khan, Akaash Odedra and Sonia Sabri, amongst others, make contemporary work in the UK that references their backgrounds in South Asian dance.

•Kenrick Sandy, Botis Seva and Kate Prince, amongst many others, originate their work from an urban street-dance background to develop dance theatre with thematic or narrative content.

•Matthew Bourne reconfigures stories that originated with ballet or film for his own company of contemporary and ballet-trained dancers.

Choreographers work in many different contexts

There are many different contexts and disciplines that require the work of a choreographer. These include:

•in education with young people, schools or youth groups

•community groups with people of different ages and mixed abilities

•text-based theatre or drama in which dance or movement is required

•opera for musical interludes, or as part of the staging

•musical theatre as musical staging of song and dance numbers

•dance competitions in folk or ballroom dance

•dance assessments and examination in a course of study

•cruise ships and fashion shows

•dance for the camera, television, film and commercial music videos

•digital interaction, using motion-capture for video games and animation.

PEOPLE WHO SUPPORT THE CHOREOGRAPHER

Choreographers making a new work need substantial support from several specialists who support the work’s creation and realization. This is to enable the choreographer to be in the studio with a creative mind, fully focused on the choreography but also aware of what else is involved in creating work for performance.

Example of Benesh notation – score for choreography of Turandot at the Royal Opera House. Notator Ann Whitley.

The dance notator

Choreography in rehearsal and as stage presentation is recorded and filmed, so that it has an afterlife and is not left only to choreographers’ and dancers’ memories of the material made.

A dance notator uses a special system for writing down choreography. At the seventeenth-century French court, Raoul Feuillet devised a system of symbols and codes to record the steps and patterns of the dances. Since that time, a number of different systems have been established. The main ones are by Rudolf Benesh, used extensively by ballet companies, and Labanotation, developed by Rudolf von Laban, pioneer in dance analysis. The systems provide significant benefits to the choreographer by recording new work and importantly by also enabling reconstruction and revivals of previously notated repertoire works.

The producer or promoter

These roles are vital in enabling a dance production to be realized. Diaghilev is perhaps the most famous producer in dance history. In contemporary dance production, these roles involve all of the following:

•financial support and funding to pay artists and production costs

•recruitment of the creative team (design, lighting, composer and so on)

•organization of performance dates, studio and stage rehearsals

•arranging auditions to choose the dancers and issuing the contracts

•seeking permissions such as music copyright

•marketing and photographic images to advertise for an audience.

Amir Giles and Marie Chabert in rehearsal.CHRIS NASH

Maud-Helène Treille and Luke Cinque White trying out ideas and creating connections.MATTHEW BALL

The rehearsal director or assistant choreographer

This is a vital person for the choreographer in creating a new work. The role can include:

•supporting the creation of the work by sharing in the emerging thoughts and ideas

•making sure that the schedule and studio space allow sufficient time

•leading a warm-up for the dancers

•rehearsing the dancers and helping them to learn new detail

•taking care of the work after it is in performance and rehearsing a second cast.

The schedule coordinator

A choreographer has to become a time-management expert in the studio. Every working environment has constraints on studio time for rehearsals of a new work alongside repertoire works. Repertoire dance companies have a schedule coordinator who does an extraordinary juggling act to make sure that everyone gets a fair amount of studio time with the right people. In school and college environments there are similar pressures when a lot of people are creating. Once the performance dates are known, the choreographer will have to work with the schedule coordinator to find out what studio time is available to them.

WORKING WITH DANCERS

Dancers as creative collaborators

Choreographers place increasing emphasis on devising movement to include creative input from the dancers. This commands respect and, importantly, appreciation of the dancers’ artistic and technical contribution to the growing work. The dancers’ finely tuned facility and training, along with improvisation skills, contribute greatly to the process of devising new movement vocabulary and form a significant aspect of contemporary choreographic practice.

In the films A Chorus Line and All that Jazz, a male choreographer is seen at the front of a studio full of sweating dancers. He is counting loudly in ‘eights’, shouting instructions and pushing the dancers to their limits, not unlike an army drill sergeant. This is hopefully something from the past. Choreographers today lead diverse groups of people who need to work as a team. Support, encouragement and communication as well as inspiration and invention are leadership skills needed in the choreographer.

A good studio ambience

In 2017, I had the privilege of watching Crystal Pite rehearsing her work Flight Pattern with the Royal Ballet. In a room full of dancers, she never once raised her voice, answered all the questions she invited from the dancers and explained in a calm, easy tone what was required. At the end, she released the dancers and turned her attention to her small child, who had been present watching the whole rehearsal. It seems that in the twenty-first century, there is a new democracy growing and finding itself in the rehearsal studio.

A YOUNG CHOREOGRAPHER’S VIEW

This quote captures very well the curiosity and passion for creativity that the job entails.

‘Movement has always been the best way of expressing myself creatively. I enjoy translating a concept into movement. It’s like a sort of puzzle most of the time. It feels like you are a creative detective in many ways – you have this idea and it is effectively a big puzzle. You have to find the links between different parts of the puzzle. You have to find the logic, the reason etc.

You don’t know where things are going to lead or where each turn will take you. I also love spending time in the studio with dancers, seeing my ideas come to life. Surprises are an exciting aspect of this process.’

Sophie Laplane, choreographer, in conversation with the author, October 2018.

CHAPTER 2

GETTING STARTED: ESSENTIALS OF CHOREOGRAPHY

WHAT, WHY AND HOW?

A choreographer enters the studio with curiosity, to investigate and to ask questions about the movement and ideas. Starting to choreograph will raise these questions:

•Why am I choreographing this dance?

•What is my idea?

•How do I start?

There are a number of reasons why apprentice choreographers begin to create. It could be because there is an urge to communicate as choreography an idea that simply won’t go away. Or it could be that there is a dancer you want to work with. It could also simply be a creative challenge. A dance may also be choreographed as a gift, tribute or celebration for someone as a special performance, or, if studying dance, it could be for an exam.

First steps.MATTHEW BALL