22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Movement Direction in contemporary theatre production is increasingly recognised and valued as a significant component of the expressive art of bodily communication in live performance. From scene changes, to character development, to dance sequences, movement direction underpins all that we see on stage and screen. This comprehensive book traces the creativity, skills, and knowledge essential to the movement director employed within the context of performance making. Key concepts are combined with insightful accounts from experienced practitioners and supported by creative tasks aimed to develop curiosity, skill, and deeper understanding of this valuable craft. Topics covered include: what is Movement Direction?; the expressive body; the actor's process; movement in time and space;? working with dance forms; context, research, and planning; Movement Direction for plays and opera and finally, working with directors.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

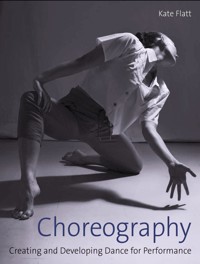

Performer Jordan Ajadi.

First published in 2022 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Kate Flatt 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4061 6

Image credits

Alain de Chamberataud, page 151 (right); Annie Spratt, Unsplash, page 79; Annika Johansson, page 126; Ardian Lumi, Unsplash, page 78; Asha Jennings-Grant, page 130 (bottom); Author’s collection, pages 24, 45, 62, 66 (top), 74, 117; Chloe Lamford, page 65 (left); Chris Nash, pages 32, 39 (bottom), 58 (bottom), 87, 118; Engravings from Rhetorical Gesture and Action by Henry Siddons (1822). Royal Ballet School Special Collections, pages 19 (bottom), 20 (left and right), 21 (left), 57 (top three), 61; Faisal Waheed, Unsplash, page 66 (bottom); Hugh Hill, page 148 (left); Jack Thomson, cover and frontispiece, and pages 2, 12, 42, 47, 48 (all), 49 (all), 51 (all). 54 (top and bottom left), 88; Jacques Callot (1592–1635), Balli di Sfessania (Tafelband), Potsdam 1921, Signatur: Wa 5604a, with kind permission of the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbuettel, page 18 (all); Jake Weirick, Unsplash, page 105; Jemima Yong, page 129; Joe Hill-Gibbins, pages 35 (all), 122, 123, 124, 125; Juan Miguel Agudo, Unsplash, page 65 (right); Karsten Winegeart, Unsplash, page 96; Kristina Pulejkova, page 130 (top); Leandro de Carvalho, Unsplash, page 56 (top); Ludovic des Cognets, pages 28, 39 (top), 54 (bottom right), 81, 136; Marie-Noëlle Robert, pages 109, 116; Márton Perlaki, page 152 (bottom right); Matthew Ball, page 73; Nikolas Louka, pages 26, 143; Oliver Lamford, page 46; Peter Simpkin, page 155 (bottom right); Picryl, pages 76 (top and bottom), 93 (top and bottom), 102; Pixabay, pages 57 (bottom), 99 (top); Ricardo Cruz, Unsplash, page 101; Ricardo Gomez Angel, Unsplash, page 104; Robert Workman, pages 106, 114, 115, 120; Royal Central School of Speech and Drama (photo by Ludovic des Cognets), pages 7, 71; Ruth Mulholland, page 149 (left); Shutterstock, pages 17, 19 (top), 56 (bottom four), 82, 83, 89, 135; Steve Cummiskey, page 84; Thomas Bonometti, Unsplash, page 99 (bottom); Tyler Nix, Unsplash, page 58 (top); Uta Scholl, Unsplash, page 16; Wasi Daniju, page 31.

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. What is Movement Direction?

2. The Professional Context

3. The Expressive Body

4. Movement in Space and Time

5. Working with Dance Forms

6. Movement Direction for a Play

7. Movement Direction in Opera

8. Movement Direction Applied in Other Contexts

9. Working in Collaboration

Conclusion

Appendix I Professional Development, Support and Further Study

Appendix II Contributors’ Biographies

Glossary

Further Reading

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONTRIBUTORS

Heartfelt thanks to all the movement directors and directors, who gave of their time for interviews and approving transcripts of the conversations. Their contributions enrich this book with the varied and enlivening accounts of their views and practice. The case studies include Vicki Amedume, Lucy Cullingford, Sarah Fahie, Jonathan Goddard, Joyce Henderson, Steven Hoggett, Jos Houben, Asha Jennings-Grant, Cameron McMillan, Ingrid Mackinnon, Diane Alison Mitchell, Sacha Milevic Davies, Anna Morrissey, Jenny Ogilvie, Ita O’Brien and Ayse Tashkiran.

I am also very grateful for rich, informative conversations held with a wider group and how that has helped shape the scope and detail of the book. These include movement director Natasha Harrison and directors David Lan, Femi Elufowoju Jr, Brigid Larmour and Matt Ryan.

ILLUSTRATIONS

I am grateful to the photographers who have granted me permission to use their work.

These include Robert Workman, Matthew Ball, Stephen Cummiskey, Chris Nash, Joe Hill-Gibbins, Chloe Lamford, Oliver Lamford and Barbara Stott. Special thanks to Jack Thomson for the cover image and also performer Jordan Ajadi for their continuing collaboration.

Images by Ludovic des Cognets are from a RCSSD Master Class, given in 2009.

Workshop participants, former students at RCSSD, also gave their permission and they include Vicky Aracas, Daphna Attias, Zoë Cob, Brad Cook, Claire Dunn, Anna Healey, Filippos Kanakaris and Terry O’Donovan.

Many thanks to the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbuettel, Germany, for permission for the commedia dell’arte images in Chapter 1. Grateful thanks also to Anna Meadmore at The Royal Ballet School Special Collections for use of the images from Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to the English Drama by Henry Siddons (1822), a text that belonged to Dame Ninette de Valois, donated to the library in 1963.

THANKS

Special thanks go to Ayse Tashkiran, movement director and educator for her support and insight, in reading and commenting on aspects of this book.

Heartfelt appreciation and admiration for the many performers, actors and movement artists from diverse backgrounds, whose talent and investigation into movement and embodiment feeds into and carries the work of movement directors everywhere.

On a personal level, I am deeply grateful for the support, love, insight and patience of my husband Tim Lamford, especially for his care of our family, when they were growing up, and whilst I was away from home working as a movement director. Without him this book would not have been written.

Actors in a movement class at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama.

INTRODUCTION

Life requires movement.

Aristotle

IN THIS BOOK

This book is about what movement direction entails and introduces the multi-faceted craft of the movement director, along with the knowledge, skills of invention, research and creative vision that the role encompasses.

Professional Practitioners

In the preparation of this book, I have drawn on my own experiences of working in theatre on plays, opera and musicals as a movement director and theatre choreographer. I have also been grateful for conversations and interviews with movement directors who are practitioners active in the field. This has resulted in contributions and accounts of their practice, which appear as examples, quotes and case studies relating to shows and productions they have created. These movement experts have generously offered accounts of how their ideas are realized through approaches to research, studio strategies, script study and collaboration as part of the challenge and creative problem-solving of the movement director’s practice. The chapters offer insight into working in the professional context, the expressive body, the actor’s process and approaches to working with scripts on plays and in the world of opera. Also introduced briefly are examples of applied skills in the context of motion capture, physical comedy, fashion shoots, contemporary circus and intimacy co-ordination in film and television. The final chapter on collaboration includes views, observations and conversations with directors on this important aspect of how movement direction in live theatre occurs.

MOVEMENT MEMORIES

The power of communication in the theatre can create a vivid, lasting memory through movement. Seeing live performance across decades has shown me how movement speaks without the need for words. These few recalled moments remind me that, by simple but imaginative means, movement leaves a resonant impression. Common to these memories are great performers, whose imagination, precision of rhythm, bodily detail and the connection to the space around them leaves an indelible imprint.

Marcel Marceau in Performance

The great mime artist Marcel Marceau performed a programme of vignettes that peopled the stage with characters who communicated volumes without words. He transformed the space by his action, playing every character himself. His skill was in communicating character detail through his masterful use of an expressive body. His gift was a precise yet playful approach that awakened the imagination of the audience, leaving an indelible image. Here are two examples from his repertoire of vignettes:

•The Tribunal

Marceau became an elderly and rather doddery judge. I recall that he walked up three steps to a podium and tripped on the top step, before then presiding over the court. This was all played on a flat stage floor, with no props or scenery. He went on to play, alternately, the prosecutor and the criminal on trial in the courtroom.

•The Mask

Marceau was playing with two imaginary, archetypal masks of comedy and tragedy, switching back and forth between them, at times quite rapidly. In this game, the comic mask eventually became stuck on his face. All attempts to remove it were in vain; his body then portrayed the limp despair of being trapped, seemingly without escape, but with an insane, fixed grin stuck on his face.

The Tempest (1610–11) directed by Giorgio Strehler, Piccolo Theatre, Milan (1978)

I saw the famous Piccolo Theatre production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest at the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival in 1984. Directed by visionary Giorgio Strehler and played in Italian, I was able to understand the whole of the play without knowing it well, nor much Italian. He used theatre magic and movement with great dexterity to create the world of the play.

The movement elements for the storm at the start of the play consisted of a stage full of quantities of billowing silk manipulated by a company of invisible people situated below the platform of the simple, wooden set. Instantly there was emphasis on movement and rhythm coming from the performers. I have never forgotten Aerial’s arrival. A slender, androgynous performer in a costume resembling a cloud of white silk descended from above. Suspended on a wire, the air spirit greeted Prospero in a high-pitched, bird-like voice. The movement involved tumbling, rising and falling on a vertical wire, assisted by an unseen operator. At one point, Prospero’s arms were outstretched and, for a fleeting moment, Aerial balanced on tiptoe, alighting on his hand before flying upward again. It was a magical revelation of what movement can do to embody the air spirit that is Aerial. Any YouTube clips available do not do justice to the lightness of the performer and their sense of flight.

Leonide Massine in Rehearsal

Massine was working on a revival of his LeBeau Danube in 1972 with Joffrey Ballet. One rehearsal day, he became exasperated with the young dancer playing the hussar (Massine’s own role). The dancer, who was very able with all the danced material, could not seem to embody the thought behind a particular moment and the focus required in the action. Standing, centre stage, he was asked to slowly raise his arm and then give a flourish as if the opening phrases of the Blue Danube Waltz made him remember something. Massine, then seventy-six years old, lost patience. He got up from his chair, went to the centre of the room and showed what he wanted from the moment. His energy from the spine and the gesture initiated from his centred torso radiated outward into the space, whilst the ensemble couples waltzed slowly around him to the slow, dream-like strains of Strauss’ Blue Danube Waltz. The years rolled away, to reveal a young man recalling a romance.

MY OWN JOURNEY INTO MOVEMENT DIRECTION

I became a movement director before I fully understood what the term meant. I had originally trained as a dancer in ballet and contemporary dance. I had studied choreography with Leonide Massine, t’ai chi ch’üan and the Alexander technique. I also travelled extensively in Eastern Europe learning, watching and researching traditional folk dance in ritual and village settings. I began choreographing seriously, after early beginnings, in my mid-twenties. After developing my own sole-authored projects, I was asked to work on the opera Eugene Onegin by Tchaikovsky, and immediately felt at home in that world. Four years later, after a clutch of other operas, and following the arrival of two children, I was phoned about a ‘new musical’. The director, Trevor Nunn, explained what might be required. I suggested naively that he might be looking for a kind of ‘invisible choreography’. The term movement director did not widely exist in 1985. I accepted the creative challenge to work on the original Les Misérables at the RSC on the hunch of ‘a funny feeling I should do this’. After discussing with my husband, a fellow creative artist in dance, we agreed that it might be hard with our two small children to manage at this time, but an important step. Who knew what the future held? I decamped to a flat in the Barbican with the children and engaged a nanny whilst my husband went on a UK tour with his company Spiral Dance. I started rehearsals at the RSC in their Barbican studios finding myself in a world of storytelling, movement, bodies and the characters of the now famous, epic, musical story.

A Voyage of Discovery

The creative process began with rehearsal days full of exploration and improvisation to discover the ensemble language and the way that the many stories within Les Misérables could be told through action. The work also encompassed the development of many individual characters, some only appearing for a few moments, others growing, changing, living and dying in the world of Victor Hugo’s novel. After ten days, out of an eight-week rehearsal period, together with the directors John Caird and Trevor Nunn, we began on the task of staging the story, aided by the famous revolving stage, of this epic novel.

The rehearsal process revealed that, although experienced as a choreographer, I had entered a new and rather different role. I led a daily warm-up, created frameworks for improvisation as movement and body work for the actors, whereby many characters and scenes emerged. I drew on my earlier studies with Massine, especially his work on the skeleton, as well as finding a sense of weight and rhythm, which gave me extremely valuable tools to explore with. Energy, emotion and different bodily states were explored and from these were developed the musical numbers. The movement improvisation tasks helped the actors find and create the undernourished bodies of beggars, the physicality of toffs, the body stories of whores and the many other characters whose powerful emotions told Victor Hugo’s epic story for the musical it was to become.

LES MISÉRABLES, DIRECTED BY TREVOR NUNN AND JOHN CAIRD, RSC (1985)

The embodiment of anger in the musical number At the End of the Day was a key moment of creative endeavour and realization. I offered an observation, ‘If you’re angry, it’s so hard to move’. ‘Can you make an improvisation for that?’ was the response. Next morning, following overnight planning, struggles with my five-year-old daughter missing her father and five-month-old son not too keen to sleep through, I made a start.

For the improvisation, I asked the actors to recall a sporting action then to physicalize it, locating the energy of the action, and where the impulse points for the movement were in the body. There was quickly a room full of action: footballers, tennis aces, cricketers and javelin throwers. On an impulse, I asked them to capture the energy of the action, focus on the point of maximum impact (as in kick or hit of the ball) and stop, and not follow through the action. This meant capturing all the force within the now still body and suspending the action. ‘What is supposed to happen?’ asked an actor. ‘I don’t know [I really didn’t] but try it and let’s find out?’

Forces and Gestures

The body shapes that emerged were full of contained force. The actors went on to add gestures associated with anger – a clenched fist, a pointed finger of accusation, two hands showing empty frustration or rage. Often the gestures needed to be pulled in toward the body, at other times they spilled outwards or upwards.

Interestingly, the force of the action went down the body, into the ground and outward into gesture. This contributed to the expression of the powerful lyrics, telling the frustration of a group of able-bodied people, with no work, angry at factory owners. With bursts of action, propelled forward and yet held back, they travelled on a straight line, arriving downstage, with the final words confronting the audience with an accusation, full of embodied anger. With this physicality, the words landed with force and clarity.

FURTHER MOVEMENT ADVENTURES

Following on from the adventure that Les Misérables became, I took up opportunities as a movement director over the next few decades on some extraordinary new productions with wonderful performers who have all taught me so much. The source material, scripts, songs and libretti that I have had the privilege to research, prepare and create within, have been life-changing in terms of ideas and the journeys I have undertaken alongside performers and directors. With that comes an affirmation that a simple hunch, as a sketched idea, can grow to become a powerful movement sequence within the world of a play. The bodies of the performers and their actions are a vital part of how a story is communicated to an audience. I have also been fortunate to have had a ringside seat to witness the work of exceptional directors and to participate with them in the development of beautiful moments of live theatre. My work, as provider of movement for productions of theatre, opera and musicals, has reaped rewards and memories that I will always cherish.

Trial and Error

Looking back to the beginning of a career of making theatre, there have been some tricky challenges. There is potential for a developing idea to not land properly, to be misunderstood or to just go wrong in the rehearsal context. This risk is always present in creative enterprise where trial and error are at the centre of creative endeavour. Occasionally, performers feel insecure or are unable to envisage how movement observations and guidance offered can help them. Aside from that, there are many pleasures and discoveries to be found in how moments come alive through the performers and how they offer expressive meaning for an audience. Despite the best of intentions, collaborative engagement with directors can entail difference in taste, opinions, ego and, at times, misunderstandings or even friction. The movement director needs to become open and a skilled, alert navigator, offering ideas and material, guiding and shaping within the flow of creative action. When this goes well, it is possible to break new ground and find new approaches and pathways.

Embracing the New

Movement direction as a career involves discovery, growth and being prepared to try new things and inspiring other people to do so with you. It can also mean stepping out of a comfort zone into a new place. It is important to remain grounded and at times to be somewhat fearless. In the maelstrom of production rehearsals and the hub of creativity, managing confidence and fear of the unknown really counts. I stand by this wonderful observation from the late, great, education theorist Sir Ken Robinson:

...if you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original...

Ken Robinson and Lou Aronica, The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything (Penguin Books, 2009)

CHAPTER 1

WHAT IS MOVEMENT DIRECTION?

Movement directors work with the physical, living bodies at the heart of a theatre production. They are called upon to create a movement language or physical style or to manifest – through performing bodies – the more enigmatic, elusive or otherwise absent parts of a theatre text.

Ayse Tashkiran, Movement Directors in Contemporary Theatre (Methuen, 2020)

Performer Jordan Ajadi in rehearsal.

MOVEMENT DIRECTION

Movement direction in contemporary theatre production is increasingly recognized and valued as a significant component of all the elements that make up live theatre performance. Movement work is developed to be subtly expressive in the body of a performer or more visible as distinct sequences and fluid transitions in ensemble creation. These can reflect reality as believable narrative serving to strengthen and delineate the world of a play or opera or offer heightened action by more abstract means.

Movement direction can involve all the following:

•Research into the source of movement and action in the script or libretto.

•Staging ensemble work as group or choral expression.

•Making movement components for scene changes in a production.

•Creation of movement ‘scape’ as physicality in the world of a play or opera.

•Creating a historical style in movement for a given context.

•Working with an audio environment, which may include music.

•Developing and enriching character in an actor’s performance.

•Working with dance forms.

THE MOVEMENT DIRECTOR’S ROLE

The movement director is engaged to develop, arrange, oversee and coach material on all aspects of movement activity for stage presentation. They operate in collaboration, in ways that their creativity and knowledge are visible within the envelope of a director’s overall concept. The authorship of a movement director becomes apparent in the physicality, action, body language and characterization carried by the performers. Movement directors collaborate, observe and accompany the performer’s process in the arena of the studio, where invention, chemistry and intuitive responses are all at play. The movement director’s role in working with performers can broadly entail all or some of the following:

•Knowledge and insight about the body as instrument of expression.

•Support and skill development as training for performers.

•Leading a warm-up for an ensemble at the start of the rehearsal day.

•Coaching dance skills for social and historical dances.

•Enabling the body and imagination to connect.

•Observing how psychological states and thoughts of a specific character are expressed, embodied and perceived by the audience.

•Enabling embodied emotion to be legible and believable in characterization.

•Drawing on skills, techniques and insights drawn from diverse movement traditions.

•Clarity in communication toward a collaborative outcome.

•Problem-solving.

WHAT DO MOVEMENT DIRECTORS SAY?

The movement director’s art and skill are probably best defined in the words of professional practitioners who work in a range of settings.

Steven Hoggett

A movement director is responsible for anything that moves on the stage with an inherent quality. This could be the performers, a piece of furniture, or an object that is flying through the air. The role means creatively engaging with three distinct aspects of theatre-making:

•Creating sequences – often to music or soundscape but without text.

•Character development – through bodily expression and physicality.

•Scene changes – as transitions within an unfolding narrative.

Lucy Cullingford

A movement director views the play through a physical lens; moves bodies, words, time and space from the functional into the epic world; navigates emotion into the physical realm expanding the character’s inner life before the audience.

Sasha Milevic Davies

Movement direction is about working with the body in action and along with that, the rhythm and spatial qualities of that action. It is incredibly important that the pacing of the action, not only is integral, but also has an influence on the world of words. It involves collaborative decisions with the director and with a team who are together creating a visual, as well as a narrative, world in the staging of a play with sophisticated use of technology, lighting and design.

Movement Director or Choreographer?

There is some debate around the similarities between the two roles. The term choreographer first emerged early in the twentieth century. The term movement director is possibly newer, although the practice is undoubtedly older. A variety of terms for movement, choreography or dance can be found in the list of creatives on a production. They include movement director, director of movement, movement by, dance director, musical staging, dance arrangement or choreography.

Similar Skills

There are inevitably crossover areas with similar skills being employed. Both practitioners organize movement, dance material and action by solving problems imaginatively and often at speed. As practitioners they may share an approach, and working methods may be similar, but the purpose behind the outcomes can be very different. Here is an outline of the two roles to help unpack the approaches to creating:

A movement director:

•Is trained and experienced with movement skills.

•Uses skill and craft to author a vision specifically for the movement world of a production.

•Creates with performers from a range of disciplines.

•Develops their work alongside the director’s vision for a production.

•Is concerned with defining a physicality relevant to, or drawn from, a script.

•Can create or arrange sequences drawn from dance forms, with an integrated purpose.

•Is concerned with embodied emotion, thought and intention of performers.

•Works on legibility of movement in space and time.

A choreographer:

•Is trained and experienced in dance technique and movement skills.

•Creates dance as abstract, thematic or narrative material.

•Is sole author, in terms of material, vision and concept for a choreographic work or ballet.

•Uses the facility and skills of trained dancers rather than actors, singers or other performers.

•Articulates meaning through shaping dance in space and time.

•Creates to music, as in dance numbers in musicals or featured dance interludes in opera.

•A theatre choreographer collaborates with a director to provide choreography to a brief.

Recognition of the Craft

The creative outcomes perceived as movement direction may or may not be recognized by critics, venues, producers and possibly audiences. A debate hovers around the fact that movement direction, when skilfully deployed, becomes fully and seamlessly integrated into the whole and does not always stand out as a separate entity from the rest of the production. The movement element of a performance contributes to enhanced storytelling, characterization that engages with the actor’s process in the rehearsal room and to the work of the director who provides the framework or envelope for the production. Choreographic authorship is more easily recognizable as a separate entity and may employ dancers’ facility, appearing as dance with music, within a work.

WORKING METHODS

Living Material

The medium of human movement, by its very nature, is central to the expressive art of communication. As a living, slippery, changeable material, it is distilled in live theatre as embodiment of character, behaviour and underlying thought, which the performer expresses. There are diverse activities involved in working with movement that are unpacked across the course of the following chapters. Embodied knowledge and a discerning eye are significant aspects of the skill set needed by practitioners working in the field. The studio and stage demand of the movement director that they have done their research, as well as offering immediacy and sure-footed instincts in the handling of performers, ideas and imagination. Their work, integrated and subsumed into the whole of what an audience experiences, undeniably contributes to making a production distinctive as a theatre performance.

Working with Actors

Movement directors work in relation to the actor’s process, collaborating on movement, observing and feeding-back in terms of how the physicality is perceived in the context of a scene. In creating movement action, the heart of ‘why’ and with ‘what intention’ within the movement will emerge in relation to the director’s vision. The actor’s process is about finding out and synthesizing information to make offers of movement from the centrality of all the other information they are carrying about the character. The answer to the question ‘Why do I move?’ is something the actor needs to discover organically, rather than have imposed upon them. In this way the movement director acts as a provocateur or catalyst to action. If formal technical instruction is involved, it needs to be clarified to the actor as such, so that it becomes part of a palette of resources for them to draw on.

THEATRE MOVEMENT TRADITIONS – A BRIEF INTRODUCTION

Theatre is an ancient art and the use of movement within it a vital and ideally integrated component. These few introduced here, out of the many theatre traditions from across the globe, can be investigated through wider reading. They have developed in different eras in different parts of the world and show that movement is at the heart of a work and that a performer’s skill is integral to the form.

She waved her arms and sketched in the air an image of a soundless voice, speaking with hands and moving eyes in a graphic picture of silence full of meaning.

Polyhymnia, the Greek muse of rhetoric and hymns, described in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus from c. 400 BC

Epidaurus Theatre, Greece.

Ancient Greek Theatre

The world of expressive bodily movement is as ancient and archetypal as the expressive art of song and the ancient charcoal drawings found on the walls of darkened caves. As was known to the Classical Greek and Roman orators, movement of the performer, along with voice and emotion, is integral to the delivery of meaning. The Greeks named nine muses as their attributes of artistic expression, and at least three of them are associated with movement and the rhetorical gestures used to accompany oration.

Movement of a choral group, portrayed on a Greek vase.

Ancient Greek theatre is a tradition with no material surviving that can confidently be said to belong to the form. Theatre performances took place at open-air festivals in honour of the gods. They were played on an open stage, called an orchestra, with a wide, stepped, almost circular arena for the audience. Performers wore masks covering their faces, requiring them to act with the whole body. This would have been physically demanding and require the use of movement and muscular tension to convey emotions, which in modern theatre or film we see in the faces of actors.

Movement... involved dances normally in a formation either on a rectangular or circular basis and while it might occasionally become wild and rapid, it was usually solemn and decorous, a style sometimes called emmeleia... literally harmony.

Oliver Taplin, Greek Tragedy in Action (Routledge, 1993)

A chorus of fifteen male performers provided singing and dancing in a series of sequences throughout a play. These provided commentary on the interaction of the characters and praised the gods. The idea of integrating an ensemble of expressive, moving bodies to tell stories has its descendants in opera with a singing chorus, in ensembles for musical theatre and in ballet with a corps de ballet of dancers.

Commedia dell’Arte

The legacy of this form of improvised theatre, which flourished in Renaissance Italy, is important for its characters, influence on performance skills, use of half masks and improvisation. Illustrations from 1700 in Giorgio Lambranzi’s New and Curious School of Theatrical Dancing (Dover Edition, 2002) give an impression of commedia dell’arte scenes in theatre performance. The form was known to Shakespeare, used by Molière in his plays and influenced the buffo or comic characters in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. Significant aspects have been documented, used in training systems and influenced the work of masters Vsevelod Meyerhold, Georgio Strehler, Jacques Lecoq and the choreographer Leonide Massine.

Commedia dell’arte characters.

There is no single name that we can attach as originator of the form, yet it is understood as having had a significant element of vibrant, movement characterization at its heart. Professional players in Italy and beyond formed travelling troupes and developed skilful comedic techniques for outdoor performances in the street, square or courtyard, as well as in theatres. There were set scenarios that relied on the wit and playful movement detail of the performers for the plots involving recognizable, known characters. The performers’ skills included mask work, dance, singing, comic routines and acrobatic skills, with a well-developed movement language of character work that was recognizable and apparent through gait, differing rhythms and behaviour. The characters included servants, known as zanni, lovers, clowns, braggarts and fighters, along with the roles of Harlequin, Columbine, Pantalone, Pulcinella and Scaramouche.

Kabuki Theatre

Japanese Kabuki theatre is a distinctive theatre tradition that is highly theatrical with elaborate costumes, make up, wigs and weaponry. Action of the performers includes distinctive stylization in the vocal work and movement. The performances are actor-centred, rather than led by a director, and the plots, usually in one act, tell stories in a way that subordinates the literary aspect in favour of theatrical effectiveness, often to suit a particular actor.

Kabuki drama.

Kabuki can be translated as comprising ‘dance-sing-skill’. The actors work with mie, translated as ‘rhymes we say’. The movement material and its inclusion show a refined form developed over years of study and apprenticeship. The movement in performance follows a pattern offering a sequence of activity that arrives at a significant tableau. Kabuki movement, though fluid and graceful, is characteristic in how, with increasingly rhythmic movement, the performer achieves a place of equilibrium, or attitude, as a significant static moment, which ranges from semi-realistic to bizarre or grotesque. Neither movement nor timing aims to be realistic but the essential quality in the movement is that of a balanced, sculptural tension.

The theatre layout is like Western theatres, with the significant feature of the hanimichi, a long, raised promenade platform connecting stage right with the entrance to the auditorium. The actors enter and leave by this, and play important scenes here, bringing them close to the audience, seated around and just below them. The actor is accompanied by the presence of a shadowy figure, a kurogo, dressed entirely in black, which in Japanese theatre tradition makes him invisible to the audience. The role is as a kind of servant to the action for help with costumes and props. Kabuki is intrinsically stylized and rich in showmanship for which the actors train through a long apprenticeship to attain their craft. The best-known role type is that of onnagata or female impersonation, where male actors who specialize in this, play young, middle-aged or old women. Male roles are the handsome man, the lord, the superhero, as well as clerks, villains and comic roles.

Elizabethan and Early Modern Theatre

Elizabethan theatre placed importance on rhetorical gesture, which has a connection with the art of expressive oratory from ancient times. The use of movement as gesture is documented in the writing of John Bulwer (1644) and in his book Chirologia, it is described as having ‘the art of manuall rhetoricke, consisting of the naturall expressions, digested by art in the hand, as the chiefest instrument of eloquence’. Bulwer outlines advice for actors and orators with a significant distinction made between natural expression and rhetorical action.

Shakespeare

We can’t go back to see what was done in the performance of his plays, but it is probable that Shakespeare considered movement a significant part of the actor’s expression. In Hamlet, Ophelia describes Hamlet’s actions in precise detail to her father Polonius (Act II, Scene 1). Her description of their encounter, and his odd behaviour toward her, suggests he is not of sound mind. Hamlet then tells the players who have arrived to perform at Elsinore, to ‘Suit the action to the word, the word to the action’ (Act III, Scene 2). He continues to show interest in the quality of movement and language in the players’ delivery. He seems to be suggesting, as an aspirant director, not to overact or play the emotions too powerfully.

... nor do not saw the air too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently; for in the very torrent, tempest, and, as I may say, the whirlwind of passion, you must acquire and beget a temperance that may give it smoothness... pray you, avoid it.

(Act II, Scene 2).

Henry Siddons

If we fast-forward a hundred years from Bulwer’s writing to developments of modern theatre, the emphasis on gestural codes, demeanour and behaviour as rhetorical action is noted by the celebrated actor and theatre manager Henry Siddons (1741–1815). Practical illustrations are given in Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to the English Drama by Henry Siddons (1822). These sixty-five engravings, published after Siddons’ death, indicate the range and scope of his observations of performers and the portrayal of intentions through gesture and physicality. Siddons’ intriguing work is an interpretation of an earlier book from 1785, by German theatre director Johann Jakob Engel.