25,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Architecture

- Sprache: Englisch

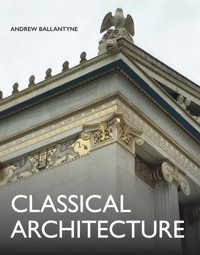

Lavishly illustrated and accessibly written, Classical Architecture takes the reader on a journey through the history of this iconic architectural genre, starting with an introduction to its origins in ancient Greece, through its resurgence across Europe during the Renaissance, to its influence on modern-day architectural design in locations as diverse as Shanghai and Washington DC. Written by Professor of Architecture and established author Andrew Ballantyne, and illustrated with over 100 photographs, this book will prove invaluable to anyone wanting to explore and understand this important and pervasive architectural style. Classical architecture has developed through many styles to become the backbone of western architecture. It was refined in ancient Greece mainly in sacred places. This architecture of finely modelled columns was taken up by the Romans and spread across their empire, changing on the way, so by the time the Roman empire collapsed it had become an architecture of arches and vaults. The monuments were impressive, even as ruins, and inspired imitation in later ages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine, Louvre, Paris, c. 1812

First published in 2023 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2023

© Andrew Ballantyne 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4166 8

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

Image credits Figs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 17, 18, 19, 26, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 36, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 55, 64, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 76, 79, 80, 88, 89, 91, 94, 95, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 107, 108, 110, 111 and 112: Shutterstock; Figs 6, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 32, 35, 37, 39, 40, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 65, 66, 67, 73, 74, 75, 77, 78, 81, 83, 84, 85, 86, 92, 93, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100 and 109: Andrew Ballantyne; Fig. 106: Rolf Hughes; Fig. 90: Gerard Loughlin; Figs 10, 13, 54, 63, 82 and 87: public domain.

Dedication

To J.J. Thomas, who knows where the bodies are buried.

Contents

Chapter One Ancient Greece

Chapter Two Ancient Rome

Chapter Three Byzantium

Chapter Four Romanesque

Chapter Five Renaissance

Chapter Six Baroque and Rococo

Chapter Seven Neoclassicism

Chapter Eight Eclectic Classicism

Glossary

Index

Chapter One

Ancient Greece

Starting in Athens

Any building put where the Parthenon is would look important. Held gloriously aloof from the everyday parts of the city, it is on a rocky plateau, the Acropolis, set apart from the rest of the city by cliffs (seeFig. 1). The building itself is a wreck. It can be seen from a great distance because of the lie of the land, and these days it is floodlit at night. From far away it makes a good impression, but when we get closer it is obviously no longer in use. The roof is missing, and so are most of the sculptures that used to embellish it. In the digital reconstruction, an idea of the building’s shape is restored, but the life is missing (seeFig. 2). Nevertheless it has a reputation as one of the world’s most beautiful buildings. In part that is because it has the status of a classic. Its beauty is not in doubt. If you do not find it beautiful, then it is your judgement that is at fault, not the building. We are educated to appreciate it.

Fig. 1 The view shows the Acropolis with the city of Athens in the background. On the Acropolis the ruined Parthenon is clearly visible on the right. The group of sunlit buildings to the left is the Propylaeion – the gateway building – with the small temple of Athena Nike in front of it. Further away, looking smaller and harder to distinguish, the Erechtheion is also visible.

Fig. 2 The Parthenon, Athens, 447–438BCE. Digital reconstruction of the most prominent classical temple.

The Parthenon is one of quite a small number of classical Greek temples to have survived – no more than fifty – some of them with just part of a single column upstanding in place. They are spread across the region that used to speak Greek, but modern national boundaries put them in different countries – the southern Italian mainland, Sicily and western Turkey, as well as the mainland and islands that are now in modern Greece. There are no surviving classical temples on Crete, although the father of the gods, Zeus, was supposed to have been born there.

Not all temples were classical in style. For example there are caves in the cliffs of the Acropolis that were used as temples. This book is about classical architecture, but not all the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome, which under a different heading might be seen as classical periods. Really we know very little about the everyday architecture of the ancient world because it has vanished, but the monumental buildings were more enduring – as they were intended to be. A classical building has columns, or – later – representations of columns. The façades of the Parthenon have columns going all the way round on all four sides. Within the space marked out by these rows of columns there is a closed building with walls that are solid except for a doorway at the end, the cella.

Fig. 3 The First Temple of Hera, Paestum, c.550BCE. An archaic temple – the oldest one illustrated in this book.

Le Corbusier was the most influential architect of the twentieth century. In his book Toward an Architecture there is a famous double-page spread with four illustrations that show two Greek temples paired with two vintage cars. The captions explain that we are looking at a temple at Paestum 600–550BCE (a Greek temple, built on land that is now in Italy, seeFig. 3) and the Parthenon 447–434BCE, and below them a Humber from 1907 and a Delage ‘Grand Sport’ of 1921. Le Corbusier’s book first came out in 1922 when the second car was brand new and would have looked spectacularly sleek compared with the old Humber, which is a very early car, dating from the year in which Henry Ford produced his first Model T. The idea with the pictures is to notice that the temples differ from one another in the same way as the cars. The older one establishes the type, while the newer one is much more sophisticated and refined.

The temple at Paestum (which the ancient Greeks called Poseidonia) from the early sixth century BCE is now classified as ‘archaic’. Its columns are used in the same way as at the Parthenon, going with a steady rhythm right round the building, but their shape is different. They taper much more noticeably as they reach the top, and their capitals spread out very wide. By contrast the Parthenon is called ‘classical’. There are other, later buildings in a similar style, but they can be bigger and more ornate, and they are called ‘Hellenistic’. The term ‘Hellenistic’ is used for the period between the death of Alexander the Great (323BCE) and the arrival of the Romans, starting with their conquest of Corinth in 146BCE. There is stylistic development across the 150 years – maybe five or six generations – that separates the temple at Paestum from the Parthenon, but now that another 2,500 years have passed we notice the similarities before we spot the differences.

When Did Architecture Become ‘Classical’?

Words keep changing their meaning, so we have to pay attention to when they are being used. At the time when the Parthenon was built, nobody thought of it as either classical or Greek. ‘Classical’ is a word that was first used by the Romans to refer to the highest class of Roman citizens – it meant the same as ‘patrician’. That sense is forgotten in current English, but if we think of ‘classical architecture’ as originally meaning ‘posh architecture’ we won’t be far wrong. ‘Classical architecture’ – meaning broadly ‘architecture modelled on Greek or Roman style’ – was not used in English before the eighteenth century.

‘Classical’ also has a sense of being the best. Archaic architecture seems to have the right general idea and good intentions; classical architecture is refined and gets it just right; Hellenistic architecture is showy and overdone. I don’t want to say that these judgements are right, but to point out that attaching the name ‘classical’ to a particular period means that we are saying that that period was in some sense the best. The earlier things are finding their way, the later things have lost their way, and the classical works are correct. Other things are judged against them. When we are talking specifically about ancient Greece, ‘classical’ normally refers to the fifth century BCE, but in a more general conversation it is used to refer to the style of the high-status architecture of that age and everything that has been influenced by it, at any time at all.

‘Style’ is another word that has changed its meaning. It starts in the Greek word for a column, stēle. It is still used in this sense in the specialised language that is used in discussing classical architecture. The row of columns that goes round a temple is called a ‘peristyle’. A temple with six columns across its front is called ‘hexastyle’. If it has eight, like the Parthenon, it is called ‘octostyle’. The temple’s base – usually with three steps at its edge going right round the building – is called a ‘stylobate’, and the columns are placed on it. Buildings without columns are called ‘astylar’.

Ancient Greece Was Not a Nation

Another word that has shifted in meaning is ‘Greek’. There had been a Greek language from Mycenean times – a thousand years before the Parthenon was built – but never a country with a national border. The word really comes from the Romans, who had the idea of the Greek speakers living in a region (which they called ‘Graecia’), but it was not a country with a unified system of government. In the same way, the Romans called the region where German speakers lived ‘Germania’.

The Greeks called themselves Hellenes, but other words were used as well. In the Iliad, which dates from maybe two or three hundred years before the Parthenon, Homer calls them Achaeans, and by that he means all the Greeks who came together to lay siege to Troy. But the same word is also used to name one of the four ethnicities that the ancient people recognised in the region: Achaean, Dorian, Ionian and Aeolian. These took their names from the sons of Hellen, whose own name has become that of the modern country – Hellas in Greek – but English persists in using the Roman-derived ‘Greece’.

For architecture, the important groups are the Dorians and the Ionians, who were not well defined in geographical or genetic ways, but came to represent a cultural polarity. The Dorians were portrayed as robust and military, with Sparta the city-state most distinctively associated with them. They were broadly associated with the territories of western Greece. The Ionians by contrast were associated with the east and with the idea of refinement and luxury. Athens belonged to that side of things, the culture being seen to have links with the landmass of Asia Minor (or Anatolia) where the modern nation Turkey now lies.

When the Parthenon was built the city-states were independent of one another – though alliances were made – and there was nothing like the modern nation. Athens was not then the capital city and not the most powerful state. Sparta had greater military power, and when Athens went to war with Sparta, Sparta eventually won (in 405BCE). Thucydides, an Athenian, lived through the years of conflict and witnessed some of the events. He wrote a history of the war, in which he comments that if you were to visit Sparta in the region of Lakonia, then you would think it was just a collection of villages, and wouldn’t dream that it had been one of the greatest cities in the world. On the other hand, if you were to find the ruins of Athens, you would think it had been at least twice as powerful as it really was.

His point was that the two places had very different cultures. The Spartans did not have a city wall, because they did not need one. Their military culture was such that if an enemy were to come close, they would be annihilated at a distance, before they ever reached the city. By contrast Athens had defensive walls and monuments a-plenty. There were walls around the city and walls that extended to the coast, so that when there was a siege, supplies could be brought in a protected corridor from the port at Piraeus 11km away. The ruler of Athens (Pericles) gave inspiring speeches that were written down and are still admired, while the Spartans are remembered for their Laconic wit – pithy put-downs backed up with physical menace.

The legacy of Alexander the Great was to spread Greek influence over a vast area south and east of what is now Greece. The Hellenistic kingdoms in these regions were huge and politically independent of one another. Culturally they mixed Greek ways of doing things with more local ways. Some of the greatest monuments of antiquity come from these regions – made possible by the wealth and concentrations of power that gave the rulers freedom to commission lavish buildings.

With the waning of Rome’s power, hundreds of years later, there was a greater sense of political centrality in this region, and there was a Greek-speaking capital, Constantinople (as we will see in Chapter 3). In 1453 it was taken over by the Turks, and became the capital of the Ottoman Empire. In those days Athens was a provincial city. The Ottomans used Nauplion as their administrative centre for the region, and it was there that the new king Otho arrived in 1832 to take his throne when the modern nation of Greece was established as a free independent country. The capital moved to Athens because of the splendour of the ruins there, making it the important place that the buildings had all along suggested it was.

The Altar of the Ancient Temple

The crucial part of a sanctuary was the altar. It is here that animals would be sacrificed. Sacrifices pleased the sanctuary’s god and obliged him or her to help. In ancient mythology Prometheus made the original people and gave them the secret of fire. He also struck a deal with the gods. He divided up a slaughtered animal and offered the gods a choice between the meat and the rest of the animal – bones wrapped up in the skin. The gods chose the skin and bones, and left the meat for the humans.

That partition of the animal was repeated with the sacrifices at temples in later ages. Animals would be slaughtered, the skin and bones would be burned for the gods, and the humans would cook the meat and eat it. At Corinth there were at least thirty dining rooms in the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore – probably more, as the limits of the site have not been found. The feasts involved far more people than the priests attached to the sanctuary. Most of the meat-eating that went on in ancient Greece was at religious festivals, and feasting could be done in the open air or in temporary shelters (tents, for example) that could come and go without leaving a trace that we can identify.

When Moses was leading his people in the desert, he set up the tabernacle – a formal arrangement of fabric and tent poles – as a portable temple. That would have been during the Greek Bronze Age – roughly a thousand years before the Parthenon. Modern weddings often use marquees for the feast, and the use of temporary awnings need not suggest an informal setting. The solidly constructed formal dining rooms must have been seen as preferable or they would not have been built at all.

The altars in Athens were important in Athens, but had relatively little significance beyond. In purely religious terms the sanctuary on the Acropolis had about the same significance as the temple of Aphrodite on Kythera, or the temple of Nemesis at Rhamnous. They were important for the cult of the particular god, and attracted pilgrims. Nowadays we know where the temples of Aphrodite and Nemesis were, but we have to imagine what they were like. They do not now have the monumental presence of the ruins in Athens.

Fig. 4 Theatre in the sanctuary of Asclepios at Epidauros, c.310BCE.

There were other places that were important to all the different Greek states. The sanctuaries at Isthmia (attached to Corinth) and Olympia held games where athletes from all the Greek states competed. At Epidauros there was an important sanctuary for Asclepios the healer, and people travelled there for the sake of their health. It is now best known for the sanctuary’s great theatre (seeFig. 4). The sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi had a more modest theatre and a running track, but it was best known for the oracle who delivered prophecies, the Pythia, and the games that were held here were known as the Pythian Games. It was a site that had great wealth and prestige because it could attract support from many states – there was widespread demand for divine advice.

These panhellenic (all-Greece) sites had the effect of bringing the different Greek-speaking states into contact with one another, forging bonds long before there was anything like a Greek nation with one central government. In each case there was a sanctuary at the heart of the activity, and these sanctuaries were not positioned for their convenience to the citizens of any city-state. There were traditions of divination – reading signs such as thunderbolts, the entrails of animals, or the flights of birds – that continued to be used when a new place was founded.

Often, though, they used places that had already established connotations. For example, at Athens the Acropolis had been fortified in even-more-ancient times and was the basis of a Mycenean settlement from a thousand years and more before the Parthenon was built. Similarly there had been a bronze age settlement at Eleusis, 25km from the Acropolis, which turned into one of Athens’ most sacred places – the home of the secretive and theatrical Eleusinian mysteries. The sanctuary at Delphi was on the slopes of Mount Parnassos, where the Muses were supposed to live – they inspired writers, musicians, dancers and astronomers.

Interacting with the Gods

Herodotus (484–25BCE) was from Halicarnassus, a Greek port that remained in the Persian Empire until it was conquered by Alexander the Great in 333BCE. Its provincial rulers had the status of kings, and the most famous was Mausolus, whose funerary monument, the Mausoleum, became known as one of the wonders of the world. That dates from a hundred years or so after Herodotus was writing, so he had no knowledge of it. He is often called ‘the father of history’ because his writings are thought to be the earliest attempt to write an account of the great events of his time and what led up to them. The great events revolved around the Greeks’ success in defeating the army of the great Persian Empire. Although the modern events are explained responsibly in a well-informed way, the background is clearly based in myths and tradition. With Homer’s Iliad we have a text of uncertain date, but it is assumed to be older than Herodotus by some centuries, and it has history in it that is so interwoven with mythology and poetic fabrication that we cannot read it as a historical account of the events, but rather as a poetic reimagining of them.

One of the striking things about it is how much the gods are involved with the events. Achilles, for example, is not only the greatest of the Greek warriors – he is also semi-divine. His father was the King of Thessaly, his mother a sea-nymph. Helen, who had been abducted by the Trojan prince, Paris, was the most beautiful mortal, but she had hatched from an egg. Her father was Zeus in the form of a swan, her mother either Leda or, in some versions, Nemesis – the goddess of retributive justice. Athena the virgin warrior and Poseidon the sea god were on the side of the Greeks. Aphrodite and Apollo were on the side of the Trojans. Zeus decided not to take sides, but the other gods were in the thick of the action, guiding weapons and inspiring the heroes.

Homer gives us a view of people acting in the world as he saw it. In this world gods and humans are interacting all the time – even interbreeding. The ancient world had no concept of the unconscious, and if you had lived then and felt moved by unexpected emotions then you would think a god had visited. You might appeal to Apollo or one of the Muses for creative inspiration, to a warrior such as Ares (the god of war) or Athena for courage, and if courage or inspiration came, you would know who to thank for it. There were local gods as well, who looked after individual wells or households, and you would want their help too.

The altars at the sanctuaries were the most direct mechanism through which the gods were obliged to take note of human affairs and to intervene in a helpful way if the sacrifices were impressive. Some votive offerings at the temples were small and personal – a clay model of a foot from someone who was lame, for example, or if someone wanted a child they would leave a model of a part of the body that was involved – but the great feasts would be public occasions when the city-state would do honour to its patron god and make sure that she or he continued to dwell in the city and intervene on its behalf. If a city were under siege then the enemy would make sacrifices to the city’s patron deity and try to persuade him or her to change sides. For such sacrifices to work the enemy would need to know the god’s secret name, which would be closely guarded.

Many altars would have been relatively simple stone platforms, suitable for cooking the meat and burning the rest of the bodies that had been slaughtered and butchered nearby. They could be decorated with sculptures round the sides, and they could be large. They rarely survive because when the old religion was overtaken by Christianity or Islam the old gods were seen as demons and the altars were there to summon them, so the altars were usually destroyed. The altars could be impressive buildings and they could be almost independent of the temples.

Fig. 5 Pergamon altar, from Pergamon (now Bergama in western Turkey, near Izmir). The altar is now at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, 166–156BCE.

The most impressive one to have survived, at least in part, is the one from Pergamon: it is now located indoors in Berlin, instead of being on a high hillside with spectacular views of the heavens above and the plain below (seeFig. 5). The arrangement there had the altar slab at its heart, with a sculpted relief on its sides (which is not so well preserved). The altar was set in a courtyard, and the whole courtyard was raised on a plinth, with the surviving sculptures on its sides. It was approached by a flight of steps, and the arrangement allowed the courtyard to be level despite the slope of the surrounding ground. This altar dates from about 300 years after the Parthenon, when Pergamon was the capital of one of the Hellenistic kingdoms. The sculptures depict a mythical conflict – gods fighting with giants – as do many of the architectural decorations in other places. The effect is lively and dynamic, with struggling muscular bodies – quite different from the calm processional mood of the images to be found, for example, on Egyptian temples.

The human body is the constant reference for Greek sculpture, whether it is attached to buildings or standing freely apart. Male bodies are often unclothed, whether in battle or at rest. Female bodies are more often clothed in flowing robes, but there are exceptions, especially in the case of Aphrodite, whose name gives us ‘aphrodisiac’.

Doric Order

There is a so-called ‘dark age’ in between the collapse of the Bronze Age (Mycenean) civilisation that built stone palaces and monuments, and the emergence of the civilisation that started to build Doric temples. This dark age did not leave buildings that could be found by archaeologists until in the late twentieth century they started using new techniques. Soil samples were taken into laboratories for analysis with chemical tests, microscopes and Geiger counters. People inhabited the same places during the dark age, but they did not build stone monuments. Post-holes, where timber columns decayed in the ground, can still be detected if the earth has not been disturbed by modern ploughs. The dates for this period are about 1100–800BCE.

The culture that we know about from after that period was certainly different from what was there before it, but there are some lines of continuity. The earliest Greek literature – the poems of Hesiod and Homer – emerge from this darkness, bringing to our eyes (by writing it down) traditions that are assumed to have been passed orally through earlier generations. Before the darkness there was writing, but the surviving documents that have been translated do not amount to literature, so it feels as if in Hesiod and Homer at last there is an insight into how people were thinking. There is in these poems a memory of historical events from the Bronze Age, filtered through understanding that is (in our terms) mythological, and which for them was clearly fundamental. In Hesiod there is an idea of earlier ages of the world that outshone the state of the present – a golden age, succeeded by a silver age, and an age of bronze, followed by the then-current state of the world. So the early world had been populated by giants and heroes who were close to the gods. I imagine that everybody knew this as a fact, somewhere in the back of their minds.

The evidence of early temples is scant and debatable. By later standards they were modest, but they served as a focus for sacrifices, and by about 600BCE there was an established model, which we call the Doric temple. If we look back earlier for an origin, then we are in the realm of contested speculations, but once the Doric temple is present, it seems to carry an authority that makes it something that others wanted to copy, refine and enrich. According to the Roman writer Vitruvius (we will hear more about him in the next chapter), Doric temples were called ‘Doric’ because they were first noticed in the cities of the Dorians (Vitruvius, Book 4, Chapter 1).

The Dorians were the people who came from the forests of the north and caused the breakdown of the Mycenean culture. Whatever traditions they brought with them would have been hybridised with the local ways of doing things. They learnt Greek. When Vitruvius mentions ‘Doric cities’ he certainly means cities in Greece, as the Dorians were not known to have left cities when they came to Greece. Their founder, Dorus (Vitruvius says, repeating the suppositions of his time), was the son of Hellen and the nymph Orseis.

By classical times the most prominent Doric city was Sparta, which was known for its austere military culture and communal living. Where architecture was concerned it was known for simplicity. The Dorian zone of influence was centred in the Peloponnese – the main landmass of south-western Greece – with related cities on some islands, in Anatolia (Turkey) to the east, and Sicily and southern Italy to the west.

Fig. 6 The so-called Temple of Concordia at Agrigento, Sicily, 440–430BCE. The original dedication is not known for certain.

The Temple of Concordia at Agrigento on Sicily is a good example of the Doric temple type (seeFig. 6). It dates from about the same time at the Parthenon, and is almost as well preserved, but we do not know its original dedication. Its value here is that it is typical rather than exceptional. Its shorter ends have six columns, so it is a hexastyle temple. The long sides have thirteen columns, which is the typical proportion – double the number of columns on the ends, plus one. The columns are fluted, so in bright sunlight we see vertical lines running up them. They rest on the stone platform – the stylobate – on which the temple as a whole sits. In this case there are four steps running round the edges of that platform; in fact it is more usual for there to be three.

These steps are sculptural rather than practical. In a small temple they can be used in the usual way, but in larger temples they are scaled up. The number of steps does not increase. So a large temple has large steps, which can make them inconvenient for humans to use. Some temples have a stone ramp built, so as to make it possible to move in a dignified way – for example in a procession – between the interior of the temple, where the cult statue of a god would be located, to the outdoor altar where the sacrifices to the god would be made in the line of his or her vision. For example, a stone ramp survives at the temple of Aphaia on the island Aegina. At Agrigento there is not, but there is a temporary modern ramp for the convenience of tourists, and it is possible that a timber ramp was placed here in ancient times when the building was in use.

The bottom of the column is cut off squarely, so it sits on the stylobate with no sculpted base in the column. At the top of it there is a capital – a sculpted ‘head’ – which in this case looks quite simple. The Doric column always has a capital in broadly this form, but with variation in how much it projects beyond the shaft of the column. The curved form here is called an ‘echinus’, which is the word for a sea urchin, but the resemblance in not immediately evident, and in English no one ever calls the capitals sea urchins. The same word is used for a hedgehog and the prickly outer casing of a horse chestnut, where the resemblance is clear. It is also the word for a copper bowl, and that is the meaning that best links with the capital. Think of it as a bowl sitting on top of the column. Then the bowl is covered with a flat square slab of stone called an abacus.

The abacus is in between the column below and the entablature above. Think of the entablature as a table top. It takes up quite a substantial part of the height of the building – almost one third of it, if we exclude the slope of the roof, more than half of it if the roof is included. The columns are quite close together – the space between them is about 1.5 column-diameters – so the stone in the entablature does not have to span very far, which is just as well, because stone used as a beam tends to crack in its underside if too much is asked of it. Stone can span much further if it is used as an arch. The ancient Greeks knew about arches, and they are to be found in utilitarian structures such as bridges, but never in high-status buildings such as temples.

The entablature is divided into two main bands. The lower one is called the architrave, and it is absolutely plain. Visually it could be a single beam running along all the column tops, but that would make it a huge piece of stone that would be impossible to manoeuvre into position without it cracking, so in fact it is made up of a series of relatively short (but still very substantial) stone blocks, each of which spans from one column to the next, with joints between them that are so finely made that they disappear from view. Above the architrave there is a frieze, which is panelled, alternating square panels (called ‘metopes’) with rectangular panels (called ‘triglyphs’) divided into three by incised channels.

The story that is usually told about this frieze is that it shows in a decorative way a memory of a timber structure. The triglyphs represent the ends of beams. So the correct place for them is directly above a column. There is usually an extra triglyph half way between each column. That is exactly the arrangement here at Agrigento. However, there is a complication. By the classical era – and even by the time of the archaic temples at Paestum – the frieze went continuously round all four sides of the building, whereas beams would have run across the building from side to side. If the triglyphs represent the ends of beams, then we would expect to see them above the columns on the long sides of the building, but on the short sides we should see just the whole length of the beam running across all the columns like the architrave, not the end of it.

So if it is a memory of a system of construction, it is a memory that has become hazy and stylised. It causes a problem for the designer every time the frieze reaches a corner. It does not make sense for two beam ends to be side by side at 90 degrees to one another. Constructionally it would make more sense if one beam rested on top of the other. What happens, though, is that in order to keep the regular geometry running round the corner, there are two triglyphs there at 90 degrees to each other, but the column at the corner is pulled closer to the next column along, so the triglyph here is not placed centrally on the column beneath it. The space between the last two columns on each side is always a little narrower than the rest. That might be to give the corner subtly more visual strength.

However, in order to keep it from being obvious, the space between the triglyphs here is slightly stretched. The triglyphs stay the same going across the building, but the adjustments are made in the proportions of the metopes, which always look like square panels, but in the middle of the façade they are slightly taller than square, and at the corners they are slightly wider than square. Along the whole of the façade the adjustments are made gradually from one to the next, so the visual effect is of continuous regularity.

We are likely to come away from the building thinking that the columns are regularly placed at the same distance from one another, and that the Doric frieze runs continuously round the building without encountering any problems. We will come back to the Doric temple in an enriched form when we reach the Parthenon below, but it is best understood if we can refer also to the Ionic temple, which is a rather different type.

Ionic Order

The Ionians were associated with western Anatolia – coastal land that is now in Turkey. They looked to an ancestor called Ion who, like Dorus, was a son of Hellen. There is, confusingly, a group of islands in western Greece that is called Ionian (between Corfu and Kythera), but those islands had nothing to do with this Ionia in the east. Three great Ionic temples were built in the sixth century BCE: the temple of Hera on the island of Samos (570–60BCE), the temple of Artemis at Ephesus (completed 550BCE), and the temple of Apollo at Didyma (540–30BCE).

This area – and indeed the whole of Greece – came to be dominated by the Achaemenid Empire – the Persians, with their capital at Babylon. The Greek cities could be at war with one another, but on occasion they banded together to fight the Persian threat from the east. The political landscape changed when Alexander the Great conquered Persia, and this threat went into abeyance.

The great Ionic temples of the sixth century BCE were the most extravagant and spectacular temples of their time, but they have not survived. The temple of Hera on Samos lasted less than a hundred years, because of either poor foundations or earthquakes, but it was rebuilt, as were the others before their eventual collapse. The Ionic pattern was similar to the Doric. The inner chamber of the temple was surrounded by columns that (with their entablature) were visible from the outside. In the case of these great temples there were two rows of columns right round the building, so the closed room of the temple, with the cult statue in it, was screened from view even more than usual.

The row of columns is called the ‘peripteron’. A temple surrounded by columns is called ‘peripteral’, and these, with a double row, are called ‘dipteral’. With a dipteral temple the effect is like a forest of columns, and one comes across the cella, the closed room, almost as a surprise. The cult statue would still have had a direct line of sight to the altar outside, and would witness the sacrifices that were made there.

Column and Capital

Every column comes at a price. There is work in it – skilled craftsmanship – and the materials for it would have to be quarried locally if possible and transported to the site where they would be finished. Increasing the size of the building, and increasing the amount of elaboration beyond the basic idea of it, added enormously to the expense, and these temples were extravagant and magnificent displays. They were in themselves sacrifices to the gods within, consuming the resources of the region that might otherwise have been used for utilitarian things such as food or fortifications. But people thought the temples were worth building. They secured the help of the gods, and they impressed everyone who travelled to visit them.

The columns in an Ionic temple are different from Doric columns. They have a scroll at the top – ‘volutes’, or two spiral curls. The column also has a distinct sculpted base, and its shaft is fluted with deeper incisions (and there are more of them – typically twenty-four instead of the twenty that are usual with Doric). You could imagine that the flutes in a Doric column are a stylised, neat and geometric version of axe cuts that might have hacked a tree trunk into shape. The Ionic flutes do not look like that. They are definite sculpted deeper grooves. In bright sunlight they make darker shadows than the Doric flutes do, so the columns look more sharply drawn, with fine lines. They are also proportionally taller than Doric shafts – typically the height is eight times the diameter of the column at its base, where the Doric is typically six diameters high. Another difference is in the frieze above the columns. Instead of the alternation of triglyphs and metopes, the Ionic frieze is continuous. It could be plain or sculpted, but it is not divided up into panels so it avoids all the Doric agonies of approaching a corner and adjusting the spacing.

There are two Ionic temples on the Acropolis at Athens. They are much smaller than the great-but-vanished temples in Ionia. In the polarity of ethnicities that made Sparta identify as Doric, Athens identified as Ionic. The Parthenon is a Doric temple and has the robustness and solidity associated with Doric that carried authority in this part of the world, as well as being appropriate to the virgin warrior Athena. ‘Parthenos’ means ‘virgin’, and it is that aspect of the goddess that is celebrated in the building’s name. However, the building is enriched with things that do not normally belong in a Doric temple, and which are more characteristically Ionic. The two Ionic temples, though, are the Erechtheion and the temple of Athena Nike. They, too, are unusual in different ways.

Ionic Temples on the Acropolis of Athens

The temple of Athena Nike was completed in about 420BCE, during a lull in Athens’ war with Sparta (the Peace of Niceas), but work on it began much earlier, after its predecessor was destroyed by the Persians in 480BCE. The dedication was to Athena as the goddess of victory, and this temple is set on the rampart, so it is very prominent as one approaches the Acropolis (seeFig. 7). The gateway building, called the Propylaea, marked the entrance to the sanctuary, but curiously this little temple has a sanctuary of its own – reached through the Propylaea but by turning right and finding a way along one of its wings, rather than going through to the main sanctuary with the other buildings in it.

Fig. 7 Temple of Athena Nike, Acropolis, Athens, 420BCE.