48,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: D.K. Printworld

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

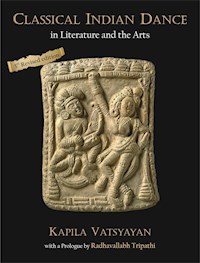

This volume is the result of many years of pain staking research in a field, which had been neglected by art historians, and thus presenting an idealistic view of the whole tradition of Indian art and aesthetics. This definitive work on the inherent interrelationship of the Indian arts is a path-breaking endeavour, treading into a domain which no one had explored. For that to happen, the author has delved deep into enormous mass of literature on the subject and has also surveyed the portrayal of dance figures in ancient temples. With Dr Kapila Vatsyayan’s profound knowledge of various dance forms as a performing artist of her own standing and having studied the sculptures and artefacts minutely, the book emerges so scholarly emanating the wisdom and know-how of a persona, endowed with the unique combination of a researcher, an art historian and an aesthetician par excellence.

The book vividly presents, analyses and critiques the varied facets of Indian aesthetics, especially the theory and technique of classical Indian dance, while doing a penetrating study of interrelationship that dancing has with literature, sculpture and music. In doing so, it surveys and analyses the contribution of great Sanskrit authors, theoreticians, playwrights of ancient and classical India such as Bharata, Bhāsa, Kālidāsa, Śūdraka, Bhavabhūti, Abhinavagupta, Jayadeva and many more along with numerous Bhāṣā scholars of arts, aesthetics and literature, covering each and every nook and corner of the Indian subcontinent.

This highly scholarly work should invoke keen enthusiasm among Sanskritists, art historians, dancers and students of varied art forms alike, and should pave the way for ongoing researches on all the topics covered within its scope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 943

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Classical Indian Dance

in Literature and the Arts

Classical Indian Dance

in Literature and the Arts

Kapila Vatsyayan

With a Prologue by

Radhavallabh Tripathi

Cataloging in Publication Data — DK

Courtesy: D.K. Agencies (P) Ltd. <[email protected]>

Vatsyayan, Kapila, author.

Classical Indian dance in literature and the arts /

Kapila Vatsyayan ; with a prologue by Radhavallabh

Tripathi

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9788124611449

1. Dance – India – History. 2. Dance in art.

3. Dance in literature. 4. Arts, Indic.

5. Sanskrit literature – History and criticism.

I. Title.

LCC GV1693.V38 2022 | DDC 793.31954 23

ISBN: 978-81-246-1144-9(HB)

ISBN: 978-81-246-1182-1(E-Book)

First edition published in 1967 by Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi

Second edition published in 1976 by Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi

Third fresh typesetted and revised edition published in 2022

© Kapila Vatsyayan (1928-2020)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission of both the copyright owner, indicated above, and the publisher.

Printed and published by:

D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

Regd. Office : “Vedaśrī”, F-395, Sudarshan Park

(Metro Station : ESI Hospital) New Delhi - 110015

Phones : (011) 2545 3975, 2546 6019

e-mail : [email protected]

Web : www.dkprintworld.com

To My Gurus

With Profound Gratitude

Contents

Prologue

Foreword

Preface to the Second Edition

Preface to the First Edition

Acknowledgements

List of Plates

Abbreviations

Introduction

1. Indian Aesthetics

2. Theory and Technique of Classical Indian Dance

3. Literature and Dancing

4. Sculpture and Dancing

5. Music and Dancing

Plates

Select Bibliography

Index

Prologue

Dr Kapila Vatsyayan can be ranked as one of the foremost art historians and philosophers of modern India. An aesthetician par excellence, she created hermeneutics for a serious study of India’s knowledge systems on art and aesthetics. She is definitely one of the very few scholars – the rare species of the modern “Vyāsas”, “Bharatas” and “Abhinavaguptas” – who tried to understand the theory and practice of arts not only on the basis of original Sanskrit texts – the scriptures or Śāstras, being skilled practitioners, they also gave entirely new perspectives.

Classical Indian Dance in Literature and Arts by Kapila ji was the first work on a critical and analytical study of the whole tradition of Indian dance with reference to Sanskrit. It is the result of her intensive studies and painstaking hard work taken up as love for labour. Dr Vatsyayan has delved deep into enormous mass of literature on the subject and she has also surveyed the portrayal of dance figures in ancient temples. With her practical knowledge of various dance forms as a performing artist of her own standing and having studied the sculptures and artefacts minutely, Kapila ji emerges here as a rare combination of a researcher, an art historian and an aesthetician. Keeping the whole peninsula in her mind, she has studied various dance forms prevalent in all the nooks and corners of the country. But then she also points out to the basic unities and the inherent philosophy behind them.

The first chapter of this work is an elaboration of the core concepts of Indian aesthetics. To Kapila ji the realm of aesthetics lies in ātman (human soul). She has created a subtle methodology and interpretative tools for understanding our knowledge traditions by the way of employing a whole set of symbols, metaphors and myths for interpreting multiplicity and dynamism of traditions in India. The metaphor of seed and sprout is taken to explain creativity. At the level of creativity, the seed (bīja) lies in eschewing the individual self, sacrificing the ego. This requires rigorous training and a life of discipline. Kapila ji rightly views this process as yajña. The metaphor of seed and tree also points out to the inner and outer levels of art creativity.

She also adopts the metaphor of the ocean, a confluence of many streams of thought to explain the organizational structures in art. This metaphor is suggestive of diversity and unity of the knowledge traditions.

As a thinker Kapila ji adhers to Advaitavāda. Her aesthetic theory creates the dialectics of a unified, undifferentiated experience. It visualizes one and the same consciousness in all the phenomena. In art creativity, this consciousness manifests in multifarious forms, moving from centrifugal to centripetal. In this way, there is fluidity and resilience of the process. The undifferentiation culminates into differentiation: the un-manifest into manifest and abstraction into concretization. The foundations of such an aesthetic theory are better supported by Śaivite monism, rather than the Vedāntic Advaita. Kapila ji rightly points out the subtle difference between the two. The Absolute in Vedānta is not self-conscious, but the Absolute in Śaivism is both self-conscious and self-luminous. It is vibrating with the potential to create a universe.

Kapila ji presents an idealistic view of the whole tradition of Indian art and aesthetics. The practice of art or learning any discipline as a matter of fact is a spiritual pursuit (sādhanā). It is for self-realization and invariably leads to a harmony within.

With this approach, Kapila ji looks towards the roots and strikes upon the fundamentals of all art forms. Each of the seven svaras (musical notes) corresponds to the seven basic elements of the physical body and they issue from the seven centres (cakras) of the subtle body. All the systems in music svara, śruti, jāti, rāga, etc. are linked to internal landscape; they stir the inner cores of human psyche. With a rare insight, Kapila ji unearths the linkage between the āhata nāda (perceptible sound) and the anāhata nāda (absolute sound). Both are manifestations of the Cosmic Sound which in the philosophy of music is described as the cause of this universe. According to Kapila ji “nāda is related to the Ultimate exactly as rays are to a gem, and just as an approach to the rays leads to the attainment of the gem itself, so the apprehension of nāda leads to the realization of the Ultimate.” Music in this way is a medium for the attainment of Ultimate Reality. Śruti – the micro interval between svaras – is the immediate expression of nāda and it invokes Nāda-Brahman. Thus, the abstractions yield the figuratives, the nirguṇa and nirākāra becomes the saguṇa and sākāra in music.

There are subtle differences between the art and aesthetic traditions of India and Europe. Kapila ji points out that “Indian dancing has a sculpturesque quality, which is rare in dance styles of the West”. The Indian dancer moves in a metrical cycle connecting herself to the cosmic rhythm. All the movements proceed from a perfect state of balance. The sthānaka (stance) serves as a footing for any beginning. It relates to the vertical median or Brahmasūtra and every movement leads to equipoise. Unlike the Western ballet, terrific leaps and gliding movements are avoided.

The second chapter is a detailed exposition of the theory and practice of classical Indian dance on the basis of authentic texts.

Discussing Bharata’s dramatic concepts, she rightly points out:

The theory and practice of Indian dance is an integral part of this conception of drama and cannot be understood without the full realization of the implications of these assertions, which have so aptly been made by Bharata. … at a very early stage of development, both these arts fused into one, so that, by the time Bharata wrote his treatise, dance was very much a part of drama and at many points of contact, both the arts were conspicuously conceived as one. The Nāṭyaśāstra thus is neither a treatise on drama alone as understood by some, nor a treatise on dancing, as believed by quite a few. The technique of Indian dancing has been actually to be culled and its principles selected with the acute discrimination from the technique of dramaturgy prescribed by Bharata.

However, Kapalaji does consider the autonomy of dance and its emergence as an independent art. On the other hand, she also emphasizes over the dependence of drama as presented in performance on the āṅgika of dance without which “the character of Indian drama is lost”.

With this focus on the interdependence between various arts, she deals with their creative process, which begins from the deep-rooted layers of human psyche. Philosophers like Abhinavagupta define these levels as the four stages of vāk (speech). Without using this complicated paradigm, Kapila ji strikes the very core of their thoughts when she says:

The dimension of the spirit, which is so often experienced by the sensitive and the aesthetically trained, and which has been called the twin brother of the mystic experience, is one which the ancient artist and the theoretician knew well; the tests only lay down the rules through which the perfect form in art can be suggested and, in turn, though which a state of supreme bliss, however momentary, can be experienced.

Kapila ji gives her own interpretation of the idea of the formless (arūpa) and the form (rūpa) in arts:

In sculpture, an image is not exactly divinity, it is merely an aspect of the hypostasis (avasthā) of God, who is in the last analysis without likeness (amūrta), not determined by form (arūpa) and transform (para rūpa).

Music and dance in this way lead to highest spiritual attainment. In dance, the body of the performer becomes the vehicle for the attainment of the soul; every gesture, movement and every attitude (āsana, bhaṅga or mudrā) paves the way for the spiritual journey within. This leads us to the idea of fundamental unity in all arts, the differences in technicalities and methodologies are just diverse ways leading to the one and the same goal.

An artist begins from the arūpa which is the abstract, the unfathomable, unknown, and visualizes the rūpa, which is perceptible, fathomable and concrete. Sāttvika abhinaya provides the best example for the transformation of arūpa – the idea and the abstract – into rūpa. All the bhāvas can be represented through physical gestures. But the abhinaya should reflect the inner soul. Even, the rāgas of music, as Kapila ji rightly points out, can be represented through saṁyuta (joined) and asaṁyuta (single) hastas with outward and upward movements. This very subtle relation between the arūpa and rūpa not only brings arts like music, poetry and theatre in close relationship, but also it opens possibilities beyond imagination. It may be possible that a rāga is being presented through its abhinaya without any vocal recital and the adept audiences have an experience of that rāga, they can hear the echoes of that rāga within.

Indian traditions of art lead to a divine experience but they are not frozen in time. Kapila ji views them in the context of pravāha-nityatā – eternality which remains in a continuous flux. She also emphasizes over the need to look at these traditions in the context of the culture which creates macro and micro classificatory systems with a scientific perspective.

The integral vision of all arts leads to a holistic perspective and Kapila ji examines the interrelationships between dance and literature in the third chapter of this work. This chapter is so far the most extensive elaboration of relations between dance and Sanskrit literature beginning from the Vedas to the best poets of classical tradition. The study of major Sanskrit plays is in fact revealing. It not only gives a picture of the ancient Indian theatre practised as per the precepts of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, it is also the first systematic attempt on systematizing the applied aspects of the Nāṭyaśāstra. In fact, Kapila ji’s treatment of Sanskrit dramas by great authors like Bhāsa, Kālidāsa, Śūdraka and Bhavabhūti can serve as a good stage manual for all these plays. While she takes into account all the types of abhinaya described by Bharatamuni, she also discusses kakṣyā vibhāga (the imaginary zonal division of the stage), various stage paraphernalia and other requisites for the performance of a particular play.

The interrelationships between dance and literature in our traditions have never been one-sided. Dancers, of course, have been drawing profusely from literary sources. The classics like the Gīta Govinda of Jayadeva have remained everlasting sources for all types of traditional Indian dances. At the same time, dance and its motifs have inspired our poets and they have weaved some of the most imaginative sequences in their writings on the basis of their knowledge of Indian dance in theory and practice. Kapila ji rightly says:

Dance has not only provided these writers with a subject for pleasure, for beauty and for poetic ornamentation in a nebulous way, but it has also influenced them in a way that they are sensitive to the minutest technical details and exhibit a knowledge of the art incomparable to any reference to it found in other literatures of the world.

She also points out how dance cast an impact in the making of many spiritual thinkers and saints; they could concretize the abstract theories and reformulate the symbols with the tools of dance in hand.

In fact, she has revolutionized our understanding of Vedic rituals from this point of view. Her brilliant analysis of the viniyoga (application) of hymns from the VājasaneyīSaṁhitā of the Yajurveda in rituals show the integration of theatricality and dance sequences resulting in a unique experience. With her wide range of knowledge about diverse traditions, Kapila ji also goes to find out the reflections of tribal music and dances in Vedic traditions.

The fourth chapter of this book entitled “Sculpture and Dancing” is the most precise elaboration of the concepts of Śilpaśāstra as reflected in the vast splendour of Indian sculptures. In fact, this is a path-breaking work and it created a model for the study of ancient sculptures which was emulated by many younger scholars working in the field. This chapter unfolds the panorama of Indian iconography and sculpture, pointing out to the

tributaries to the main river of the experience of life and art in India. The strong current of the earliest centuries of the Christian era passes through the torrents and uproars, exuberance and abundance in the Kuṣāṇa and Amarāvatī periods; it settles down to the flow of a mighty river in the Gupta period with immeasurable depth below and an undisturbed quiet flow on the surface.

She rightly points out that these sculptures present the philosophy and vision of seers and great poets. The figures become embodiments of the cosmic idea and architecture a reflection of the Cosmic Design. The symbolism behind Indian sculptures is aptly unravelled here. The dancing figures, created with a rapturous intensity, recreate the Cosmic Movement, the rhythm underlying them echoes the eternal chores.

In her study of the sculptural representations of karaṇas in Cidambaram Temple, Kapila ji has reorganized Bharata’s karaṇa system. This very intensive study has, in fact, become a manual for dancers and performing artists for a training into the mechanics and kinetics of human body.

These researches by Kapila ji have unearthed some unknown facets of our culture and have also led to restoring the missing links. For example, in her study of dance and music traditions, Kapila ji informs about the custom of singing the praise of a diseased person. Along with eunuchs, ladies and various other classes the of society, a pāṇivādaka used to come to narrate the deeds of a departed soul as a part of the funeral rites. She connects this pāṇivādaka to pāṇighna as mentioned in the Vājasaneyī Saṁhitā. The Ayodhyā-Kāṇḍa of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa gives a graphic picture of songs and narratives about Daśaratha following his sad demise.

It was because of their first - hand knowledge of the practical aspects of the Nāṭyaśāstra that she could clear a number of misunderstandings which the other researchers in the field had committed in their studies of the karaṇas as described in Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra. T.N. Ramchandran, B.V.N. Naidu and others who had made attempts at identifying the karaṇasin the Br̥hadīśvara and other temples on the basis of the readings in the fourth chapter of the Nāṭyaśāstra regarded karaṇasas static postures. Karaṇa being the basic unit of dance is the combination of several specific movements as well as gestures by hands and other limbs. The sculptures in ancient temples present only the final position the performer would attain after completing the whole sequence of these movements.

The division of human body into aṅgasand upāṅgasis well known to the practitioners of classical dance and theatre. However, it is Kapila ji who tells us the distinctive nature of our understanding of human physiology as different from the Western standards. In our tradition, “the basic anatomical structure of human form is more important than accessories of muscles and tendons that cover it” – she says. In this tradition it became possible therefore to “analyse human body in terms of a set of geometrical and mathematical laws of places and surfaces”.

I take this opportunity to congratulate D.K. Printworld for bringing out the third edition of this magnum opus by Kapila ji. This volume has since long been in demand. Although highly regarded for her immense contribution as a culture activist and as an organizer, Kapila ji also excelled as a philosopher, art historian and aesthetician. The present publication, I believe, will create a better understanding about her literary oeuvre and initiate fruitful discussion on our heritage.

Radhavallabh Tripathi

Foreword

With India’s attainment of independence and of her rightful place in the brotherhood of nations, the world has begun to look at India with new eyes. One consequence of this sudden upsurge of interest has been a glut of books dealing with various aspects of Indian culture – music, dance, costume, jewellery, art-crafts, etc. – generally hastily written and often full of errors and even misinformation.

In this climate of confusion Dr Kapila Vatsyayan’s book on Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts comes as a breath of fresh air, clear, incisive and invigorating. The product of years of diligent study of dance texts, careful research and exploration, patient analysis and long practice with the most revered teachers of the art, supported by a single-minded devotion to the cause of an art form that had suffered a near-total eclipse at the beginning of the century, the book may be said to represent a singularly happy merging of two traditions of learning – even of two cultures as it were: only in this case both humanist. For Dr Vatsyayan has not only utilized the repositories of tradition or the able guidance of an erudite scholar like the late Dr Vasudeva Saran Agrawala (under whose direction she worked for her doctorate in Fine Art at the College of Indology, Banaras Hindu University); she has also brought to bear an analytical approach to the ancestry of dance movement – so integral a part of the evolution of modern dance abroad.

No student of Indian cultural history can fail to notice one special feature of the Indian situation: it was usual for the Indian author, poet, artist, musician or dancer to dedicate his or her creation to a divinity or to a r̥ṣi (sage), thus concealing the artist’s own identity. The author of the Nāṭyaśāstra was no exception. It is impossible to identify or date him precisely; it continues to be a plausible theory that the text was compiled much later by a disciple in the tradition, to be preserved in the form in which we know it today. The treatise conforms to the tradition in another important aspect; like all other texts it quotes earlier authority. As, however, none of the material thus referred to is available, the Nāṭyaśāstra stands unique in its solitary splendour. While this isolation might have been the result of a natural tendency (particularly when tradition was preserved orally and the strain of memory was consequently always great) to consign older treatises so oblivion in favour of a newer and more comprehensive compendium of the tradition, it undoubtedly enhanced the importance and authority of the Nāṭyaśāstra for successive generations.

Though the Nāṭyaśāstra continues to have its importance for all scholars of the dance and the theatre arts generally, it was inevitable that regional styles should develop and that the commentaries should adapt themselves to accommodate and even provide justification for these variations. Some of these commentaries, such as Abhinavagupta’s for example, have in course of time themselves attained the status of a sourcebook of tradition. Thus, frequently, the dance teacher and the serious dancer – while conscientiously following the tradition or a sourcebook of authority – have in fact been called upon to exercise a meticulous selective judgement: the greatest have met this challenge with conspicuous success, thus enriching the tradition while following it.

Any attempt at reconstructing a history of the classical dance in India, therefore, would rely not only on dance texts and commentaries, down from Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra but of necessity delve deep into what was preserved in the practising tradition of preceptors as well as dancers. Furthermore, to correlate material from these two parallel sources into a meaningful pattern, the historian would have to study classical literature for its numerous references to dance and dance practice as well as to its vividly expressive and illuminating use of dance metaphor. Finally, continuous cross-reference to sculptural material would be called for not only to establish regional patterns but also to indicate chronological sequences. In other words, a historical study of the art of dance in India would call for a complex inquiry involving several disciplines; it would also call for skills not generally considered necessary equipment for scholarship. It is singularly fortunate that Dr Kapila Vatsyayan combines these skills with the scholar’s rigorous training and the artist’s sensitivity and insight. The result is this book: a masterly presentation of the aesthetic as well as the historical aspects of classical Indian dance, rendered with rare authority and fine judgement. That the analysis of certain sculptures in terms of dance movement provides new light for the understanding of classical sculpture also (e.g. the śālabhañjikās and flying figures) is matter for further commendation: it is obvious that this gain is not merely incidental but one of the aims pursued and ably fulfilled by the scholar.

I commend this well-documented and superbly illustrated work without reservation to all scholars and lovers of Indian dance.

Rai Krishnadasa

Honorary Director

Bharat Kala Bhavan, Benares

Preface to the Second Edition

The need for a second edition of a research publication, which by its very nature was heavy reading requiring patience, has been a matter of some gratification and fulfilment.

It would be natural for the readers to expect a second edition, to also be a revised edition with enlargements and modifications. The author too would have liked to meet these expectations had it not been for the fact that a truly revised edition would tantamount to the writing of three other books. A mere updating of the material would do the subject no justice.

The state of scholarship in the field twenty years ago was rudimentary and materials though known had not attracted the attention of scholars. Over these years, an increasing number of scholars both Indian and foreign have been engaged in serious, systematic researches of the traditional performing arts of India. This has resulted in a sizeable body of primary and secondary textual source material coming to light. Also recent archaeological excavations, particularly those conducted in Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, Soṅkh and Mathurā, have laid bare examples of early Indian sculptures which are exceedingly important from the point of view of a study of movement. Besides these, there has been further work on medieval monuments, particularly those of Udayeśvara temple in Madhya Pradesh and Koṇārak in Orissa. A consideration of all this material would have meant a rewriting of the present text, so as to incorporate the findings in the existing framework: it would also demand the extension of the time limitation the original work had set upon itself to a much later period. This would be particularly true of the great wealth of the traditions of mural and miniature paintings which have aroused enthusiastic interest of scholars and art historians during the last two decades.

The Preface to the first edition mentions the Nr̥tta Ratnāvalī and the Saṅgītarāja and some other works which could not be considered. It would have been logical to include analysis of these texts in the second edition. A perusal of these and many others which have since been published convinced the author that a fuller analysis of the material contained in these texts demanded a separate supplementary volume and not an enlargement of the present one. Important amongst these is the Bhoja’s Śr̥ṅgāraprakāśa, Ashokamalla’s Nr̥tyādhyāya, Vācanācārya’s Saṅgītopaniṣat Sāroddhāra, Śubhaṅkara’s Hastamuktāvalī, Mahāpātra’s Abhinaya Candrikā, the disputed text of Govinda-līlā-vilāsa from Manipur, Aṭṭaprakāram and Kramadīpikā from Kerala, and many others. Many of these belong to the medieval period and open up a new field of exploration of the deśī traditions which constitute a parallel and complimentary stream to the mārgī or all that has been considered here. After careful consideration of the material, the author came to the conclusion that it would be more profitable to follow the present study with a supplementary volume supported by charts and glossary rather than to revise the present text which seeks to present a unified picture of one stream, over a limited period.

What is true of the textual material also holds good for the literary works. Here also a larger body of Sanskrit literature is now available and one can no longer restrict consideration of Sanskrit writing to the thirteenth century. Dramatic writing continued until seventeenth century and in some cases even later. A comprehensive account of all this would also demand an independent volume and not a revision. Also, concurrent was the evolution of Indian languages, and the developments in theatre, music and dance reflected in these works. The author has attempted to survey these literatures in these years and the results of these in relation to the development of dance and dance drama, dependent primarily on the literatures of these languages, have been incorporated in a volume on traditional dance-drama forms under publication by the National Book Trust. The study takes into account this later Sanskrit drama and the growth of Indian literatures: in this respect it should be considered a supplementary volume which attempts to establish the multiple continuities.

As has been mentioned above, new evidence of dance and movement in Indian sculpture has come to light. Besides, there has been a substantial increase in a detailed analysis of other monuments of the medieval period. Consideration of this material would demand the enlargement of the present chapter on Sculpture and Dancing manifold. Of particular relevance to the present study would be the study of the sculptural reliefs of the Śārṅgapāṇi and Nāgeśvara temple in Kumbhakoṇam and some others which have cleaned up in Śrīraṅgam and Jagannātha Purī. Apart from the Indian material, a natural extension would be to take into account the prolific depiction of the movement of the dance in monuments of Asia ranging from Afghanistan to Indonesia and Cambodia. All this could not be contained in the present volume, because it would need the addition of at least another 400 plates. Thus instead of presenting a few scattered examples the author has already begun working on a comprehensive monograph on karaṇas which it is hoped will be published by the Department of Archaeology, Tamil nadu. Repeated visits to the three sites of Br̥hadeśvara, Cidambaram and Śārṅgapāṇi have convinced the author for the need for a complete re-evaluation of the subject, notwithstanding the valuable work of Shri C. Sivaramamurti in his Nataraja in Indian Art, Thought and Literature and the unpublished work of the late Shri T.N. Ramachandran.

Separately, papers have been presented in two succeeding International Congresses of Orientalists in Ann Arbor and Paris on the sculpture reliefs relating in Prambanan and Borobudur and those of Cambodia and Burma. These are under publication.

The whole sphere of painting had to be excluded in the first edition on account of the limitation of space and paucity of funds. This time also, it could not be included for the same reasons, and another, more significant, what appeared to the author and to her eminent gurus like the late Dr Vasudeva Saran Agrawala and Dr Moti Chandra to be scanty material, of mural traditions and the stereotyped repetition of the stylized pose, in miniature painting has indeed turned out, on deeper digging, to be an unparalleled documentation through line and colour of the history of choreographical patterns, movement and costuming. The author has been able to collect data relating to dance and theatre forms from the earliest prehistoric cave paintings, pottery and ceramics to the company school of the British period. Most significant amongst these is a sizeable body of paintings from the mural paintings of the Vijayanagara and the Nayak schools, and the documentation in the monuments of Kerala, both temples and palaces, which have been cleaned up by the Archaeological Survey of India. Knowledge is no longer restricted to the Mattanacherry and Padmanabhapuram palaces. Alongside has been the unravelling of many valuable sets of Jaina miniature painting. The three volumes of Jaina Art and Architecture, Moti Chandra and Karl Khandalavala’s work on New Documents in Indian Painting and the Moti Chandra’s last book on Studies in Early Indian Painting have thrown significant light on these. The evidence relating to dance in these and much else, which remains unpublished (but to which the author has had access fortunately), is immense and an analysis of this will no doubt present new facets of the performing arts. Neither the present format of the book, nor the expenses involved would allow the inclusion of this material. Since the field of painting is integral to the basic framework, the Sangeet Natak Akademi plans to bring out a companion volume on the subject.

The chapter on Music and Dancing was considered proportionately brief and inadequate by some critics. While it would be possible to enlarge the scope of the chapter to include earlier and recent publications of musical texts, the author did not consider it necessary to change the basic structure of the book merely to include more textual material much of it adequately dealt with by other scholars. Nevertheless, the author’s exploration of the oral traditions of music as pertinent to dance styles revealed that there was a vast storehouse of regional musical traditions which lay untouched. A consideration of this material would necessitate a technical examination of the compositions, supported by charts, notation of notes and movement, line drawings and the rest. All this work could not be undertaken by the publishers. The author hopes that younger scholars will pursue this line of inquiry and conduct such technical investigations. Indeed, the author is happy to say that two scholars have begun working in the field.

And finally no account of the dance and the Indian performing arts would be complete without taking into account of the variegated and significant living traditions still extant in tribal and rural India. Their contribution in shaping the traditions of the classical arts cannot be overlooked. This distinct though related field had to be investigated: the author has made an attempt at identifying this contribution and the mutual dependence of the two traditions of the literary and the illiterate, the mārgī and the deśī in a publication entitled the traditions of Indian Folk Dance published by the Indian Book Company. Many aspects of the Nāṭyaśāstra, lost to the classical arts, live and vibrate in the tribal and rural dances of India.

The above enumeration will perhaps convince readers that although the author shared their anxiety for a second revised and enlarged edition, the source material was far too vast and immense to commend such a course of action. Thus, instead of rewriting an old book, the author preferred to write supplementary works which would be a natural filling up of the basic framework followed in the original work. Also, the author is of the belief that the original work continues to provide the foundation of an approach to the study of dance and has validity.

This belief has been confirmed and supported by the reception which was received by the original work from scholars across diverse disciplines, ranging from Dr G.C. Pande, Dr V. Raghavan, Shri A. Ghosh, Dr N.R. Ray, Dr Karl Khandalavala to Reginald Massey, Betty Jones, Renee Renouf and others. Also, it is gratifying to note that scholars and students have begun to follow a methodology of research in the Indian Arts which aims at a total (albeit perhaps not a holistic) view rather than a fragmentary and unidimensional approach.

-Kapila Vatsyayan

New Delhi

30 June 1976

Preface to the First Edition

The present study is the result of some fifteen or more years of labour in a field which has, perhaps because of its very nature, received inadequate attention in the past. As a practical student of classical Indian dance forms I had found it necessary to examine and understand the theoretical bases on which the tradition of the dance and the traditional techniques had been built. The gurus and masters, hereditary repositories of what were unquestionably the authentic traditions and techniques of Indian dancing, could only provide inadequate or unsatisfactory answers to many of the theoretical questions that arose in my mind. This impelled me to conduct my own research into the original texts. The relationship of the arts, I thus observed, and the insights I gained encouraged me to pursue the detailed study of the field which forms the subject of the present work. I consider it my good fortune that I should have been led to the subject by what may appear an indirect route, because without this practical background I would have found it far more difficult to reach the bridge from the theoretical tenets to the vast and varied field of their application to dance practice. It is the discovery of such bridges and the clear demarcation of routes across them that has been my chief purpose in the present study. I may be permitted to express the belief, in all humility, that the purpose has been achieved. I trust that the lines of study indicated here will be extended to other fields which are, as I have attempted to demonstrate, inseparably related.

The size and nature of the field was formidable and I had naturally to restrict myself to what could be spanned by a unified study. Geographically its scope extended from Manipur to Gujarat and from Moheṅjo-daṛo through Khajurāho to Kerala. It was not only the archaeological sites scattered over this vast area or the objects recovered from them that had to be surveyed. The different local traditions of the schools of classical dancing preserved in isolated pockets throughout the country had also to be studied; and patient solutions found to intricate problems through personal contact with ageing gurus who represented the precious oral tradition of classical Indian dancing and who alone could provide the insight which would illuminate a study of so complex a field.

While the rasa theory is common to all Indian arts, a parallel study of the different art forms in relation to this theory has not been undertaken before. Indeed, it may justifiably be said that western scholars and art critics have generally devoted greater attention to the continuous study of the theoretical foundations of artistic practice than has been the case in India. Of course, to a large extent, this has resulted the very nature of western and Indian artistic theories. In the west, the theoretician as well as the practising artist in every field of art including literature has been actively concerned with “significant form” and has therefore generally studied several arts together or in relation to one another. In India, however, because of the emphasis placed by the rasa theory on the evocation of a mood or the attainment of a “state of being”, both the artist and the theoretician have tended to be concerned primarily with technique. This concern with technique has tended inevitably to isolate one art from another because techniques are specific and exclusive.

While the present study has, I believe, provided the groundwork for a complete historical study of classical Indian dancing and the evaluation of its different forms, the limits within which I have worked must here be clearly stated. I have dealt, in some degree of detail, with literary and sculptural material up to the medieval period. It would be logically consistent to continue this study into the beginning of the modern period, and it is my hope and wish that such a study will be undertaken in the near future. But it is obvious that this would require the collaboration not only of a large number of individual workers but also of regional institutions. Since from the medieval period onwards the unity provided by the Sanskrit texts is no longer sustained, the study would have to be extended to material in a number of regional languages. Apart from the difficulty of access to such language material and the problems of transliteration, translation and interpretation which might well prove too large for the capacities of any single individual, it is even possible that the diversity of the material might only blur the outline of the continuity provided by the Sanskrit tradition.

It has been a part of my good fortune, referred to earlier, that in the course of practical training in the different dance disciplines, I have been able to establish contacts with and receive valuable guidance from a number of gurus of dancing and ustāds or heads of gharānās of music, and I have naturally profited by the material thus made available. But obviously, a history of the theoretical foundations of Indian dancing cannot rely on such fortuitous circumstances.

Most of my literary and sculptural source material is known. My purpose was not so much to bring new material to light as to organize and correlate the existing material in a pattern of significance for the historical study of the classical Indian dance. In the field of sculpture particularly it was considered desirable to refer primarily to known examples in order to facilitate the main argument. An endeavour has been made to analyse sculptural representations of dance scenes in terms of dance poses and dance movement and thus to establish the close relationship between the two art forms.

The use of literary material has been more or less analogous. Though I have considered a number of unpublished manuscripts relating to dance in Indian libraries and abroad, I have based my argument in the main on published works. I would have liked to include in my examination some recently published manuscripts, specially Jayasenāpati’s Nr̥tta Ratnāvalī and the Saṅgītarāja and some other works published in Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and Assam. It was not possible to do so because the press copy had already been handed over and the press was unable to cope with additions during the years that the book awaited publication.

In the field of music greater emphasis has been laid on practice than on literary and other evidence; this was considered necessary to bring out the complete interdependence of music and dancing. A detailed analysis of texts of music was deliberately left out, on account of the obvious reason, that much valuable work has already been done on both textual and critical interpretation.

It is hoped that this analytical study will give the reader a clear picture of the interrelationship of the Indian art forms and of their common theoretical basis, and help him to recognize the true character of the Indian dance as the highest artistic integration of the forms and ideals of literary as well as audio-visual arts.

Work of this nature cannot be undertaken without help and guidance from many people and I unhesitatingly acknowledge my indebtedness.

Amongst the gurus from whom came my first insights into the great integrating power of the dance, I remember the late Minakshisundaram Pillai and Bharatam Narayanaswami Bhagavatar. To late Guru Amobi Singh, the late Mahabir Singh and Achchan Maharaj, my revered teachers of Maṇipurī and Kathak dance respectively, I owe my awareness of the vast body of tradition embodied in Indian dance styles, and the intricacy of thought to which they give visual form. To Shrimati S.V. Lalitha and Shri Debendra Shankar, I am grateful for the experience of Bharatanāṭyam and Uday Shankar styles. My training in the principles of movement analysis and dance notation with Dr Juana de Laban, daughter of Dr Rudolf von Laban, was not only a stimulating experience but a very fruitful one in my subsequent studies.

Scholars in the field of Indian studies have guided me in the search for solutions to many problems that arise in correlating the academic with the oral traditions of the arts of music and the dance. I recall with gratitude some enlightening discussions on the content of the dance for which Mahāmahopādhyāya Paṇḍit Gopīnātha Kavirāja kindly gave me the time. I acknowledge also Dr V. Raghavan’s willing help and guidance in addition to the benefit derived from his own studies in the field. Above all I am profoundly indebted to the late Dr Vasudeva Saran Agrawala, who as my research supervisor for a doctoral thesis I presented on the subject some of the material of which forms the basis of the present work, was not only a meticulous and exacting critic but also an inspiring guide.

To Shri S.H. Vatsyayan I am indebted in many ways and on many planes. The first insights into the relationship of word and movement came through many fruitful discussions. Later, his logical incisive criticism and his unquestioned help and support in all aspects of the work were both a source of encouragement and a challenge.

The Directors of several museums, and in particular Rai Krishnadasa (Bharat Kala Bhavan, Benares), and Dr Moti Chandra (Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay) have given me many valuable suggestions. Association with them and their work has also helped me to pursue many lines of thought to definitive ends.

Dr A. Ghosh, Director-General of Archaeology (now retired) and officers of his department have been most helpful in providing photographs and other illustrative material. Other sources of photographs have been separately acknowledged.

Dr Nihar Ranjan Ray and Dr Vidya Nivas Misra read the manuscript and made many helpful suggestions for which I am grateful.

I thank also the officers of the Sangeet Natak Akademi for their patience in seeing the book through the press. I am particularly sensible of the compliment implicit in the Akademi’s acceptance of the present work as the first in their programme of research publications.

-Kapila Vatsyayan

New Delhi

December1968

Acknowledgements

Archaeological Survey of India, figs 3, 5-6, 16, 22-23, 27-39, 41-42, 45-47, 58, 60-62, 65, 68, 75-76, 81, 83-84, 87-89, 91-92, 94-131, 133-34, 136-38, 142-45, 150-51, 154-55; Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland, USA, fig. 70; British Museum, London, UK, figs 63-64 and 66; Brundage Collection, San Francisco, USA, fig. 148; Fergusson’s Tree and Serpent Worship, fig. 67; Indian Museum, Calcutta, figs 4 and 57; Jodhpur Museum, fig. 90; Lucknow Museum, figs 14 and 59; Madras Museum, fig. 13; National Museum, New Delhi, figs 1-2, 9-11, 44, 72-73, 139 and 147; Patna Museum, fig. 7; Publications Division, Government of India, figs 24-26; Sarnath Museum, figs 48 and 74; William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas, USA, Cover Photograph, figs 93, 132 and 146; Shri Vatsyayan, S.H., figs 15, 17-20, 40, 50-55, 77-79, 82, 85-86, 140-41, 149, 152-53; Musee Guimet, Paris, fig. 69; Archaeological Museum, Gwalior, figs 71 and 135; Museum of Fine Art, Boston, USA, fig. 43.

I should also like to acknowledge with gratitude the willing and unhesitating assistance of Smt. Uma Anand and Shri Shungloo for the pains they have taken in going through the proofs and seeing the second edition through the press.

List of Plates

fig.

1 Haṛappā: Statuette,3000–2000 bce

2 Moheṅjo-Daṛo: Figurine,2500–1500 bce

3 Bharhut: Cuḷakoka Devatā, 2nd century bce

4 Bharhut: Sudarśanā Yakṣī, 2ndcentury bce

5 Sāñcī: Yakṣī, North Gate, 1st century ce

6 Sāñcī: Yakṣī, East Gate , 1st century ce

7 Bodh-Gayā: Girl Climbing a Tree, 1st century bce

8 Pompeii: Statuette of Girl,1st century bce

9-12 Mathurā: Railing Figures, 2nd and 3rd century ce

13 Amarāvatī: Woman under Tree,2nd and 3rd century ce

14 Manipuri: Female Torso, 5th century ce

15 Ellorā, Vākāṭaka: Female Figures, RāmeśvaraCave, 6th century ce

16 Māmallapuram: Yakṣī, 6th century ce

17-20 Khajurāho: Wall and Bracket Figuresfrom Lakṣmaṇa, KandarīyaMahādeva and Viśvanātha Temples, 11th century ce

21 Champa-Tra-Kieu: Detail of Pedestal, 8th century ce

22-29 Bhubaneswar: Wall Figures from Rājā Rānī, LiṅgarājaandMukteśvara Temples, 11th century ce

30-34 Belūr and Halebiḍ: BracketFiguresfromCennakeśava and Hoyasaleśvara temples, 12-13th century ce

35-36 Pālampeṭ: Bracket Figure,13th century ce

37 Sirohī Mīrpur: Wall Figure, 13th century ce

38 Ranakpur: Wall Figure Neminātha Temple, 14-15th century ce

39 Ābu: Bracket Figure, ĀdināthaTemple,13th century ce

Flying Figures

40 Udayagiri: Vidyādhara, Rānī Gumphā, 2nd century bce

41 Gwalior:Flying Gandharva, 5-6th century ce

42 Deogaṛh: Scene from the Rāmāyaṇa, 5th century ce

43 Central India: Vidyādhara, 5th century ce

44 Aihoḷe: Flying Gandharva,Durgā Temple, 6th century ce

45 Ellorā: Flying Figure, Kailāsa Temple, 7th century ce

46 Paṭṭadakal: Vidyādhara, Virūpākṣa Temple, 8thcentury ce

47 Nālandā:Niche Figure, 6th century ce

48 Sārnāth: Flying Figure, 6th century ce

49 Rājim: Yakṣa, Rājīvalocana Temple, 8thcentury ce

50-55 Khajurāho: Vidyādhara and Gandharva, Dulahdeo Temple, 11thcentury ce

Dance Scenes

56 Khaṇḍagiri-Udayagiri: Frieze of Dancers, Rānī Gumphā, 2nd-1st century bce

57 Bharhut: Panel from Ajātaśatru Pillar, 2nd-1st century bce

58 Bharhut: Panel, South Gate, Prasenajit Pillar, 2nd-1st century bce

59 Mathurā: Dancers and Musicians at Nema’s Feet, 1st century ce

60 Sāñcī: Dance Scene, Pillar South Gate, 1st century ce

61 Sāñcī: Dance Scene, West Gate, 1st century ce

62 Sāñcī: Mallas of Kuśinagara, North Gate,1st centuryce

63 Amarāvatī: Rail Cross-Bar depictingthe Mandadhatu Jātaka,2nd century ce

64 Amarāvatī:Dance Scene, Railing Pillar, the Nāga Campaka Jātaka,2nd century ce

65 Amarāvatī:Medallion, Adoration of the Buddha’s Bowl,2nd century ce

66 Amarāvatī: Internal Face on Intermediate Rails Outer Face, 2nd century ce

67 Amarāvatī: Medallion – Internal Face of Frieze of Outer Enclosure,2ndcentury ce

68 Amarāvati:Panel,2nd century ce

69 Gāndhāra: Dance Scene, 3rd-4th century ce

70 Gāndhāra:Dance Scene, 3rd-5th century ce

71 Pawaiya, Gwalior: Dance Scene, 5th century ce

72 Deogaṛh: Dance Panel, 5th century ce

73 Deogaṛh: Dance Panel, 5th century ce

74 Sārnāth: Dance Scene on Lintel,5th century ce

75 Auraṅgābād: Cave VII, Tārā Dancing,7th century ce

76 Ajantā: Dancer and Musicians,7th century ce

77-82 Khajurāho: Dance Scenes from Lakṣmaṇa,Kandarīya Mahādeva, Viśvanātha and Jagadambī temples, 10-11th century ce

83 Bhubaneswar: Dance Panel, Paraśurāmeśvara Temple,8th century ce

84 Bhubaneswar: Dance Panel, Paraśurāmeśvara Temple, 9-10th centuryce

85 Bhubaneswar: Reclining Figure,KapileśvaraTemple,11th century ce

86 Bhubaneswar: Dancer,11th century ce

87 Bhubaneswar: Ceiling Panel, Mukteśvara Temple, 10th century ce

88 Ābu: Dancing Deities, Tejpāl Temple, Dilwāṛā, 12-13th century ce

89 Ābu: Dancers with Female Deity, Tejpāl Temple, Dilwāṛā, 12th century ce

90 Jodhpur: Frieze of Dancers, 10th century ce

91 Sīkar: Musicians and Dancers, Harṣagiri, Purānā Mahādeva Temple, 10th century ce

92 Survāya:Ceiling Panel, Viṣṇu Temple, 11-12th century ce

93 Cāḷukyan: Śiva and Pārvatī on Nandī with Attendants, 10th century ce

. 94 Survāya:Dance Panel, 12-13th century ce

95 Markaṇḍa:Dancer, 12-13th century ce

96 Markaṇḍa:Drummer, 12-13th century ce

97 Gwalior: Pillar Reliefs, Sāsbahū Temple, 11th century ce

98 Kerala: Dancer with Accompanists, Trivikramaṅgala Temple, 12th century ce

99 Kerala: Kudakuttu Dance, Kidaṅgur Temple,11th century ce

100 Pālampeṭ: Frieze, Musicians and Dancers, Rāmappā Temple, 13th century ce

101 Pālampeṭ: Dancer with Accompanists, Rāmappā Temple, 13th century ce

102 Śrīśailam: Dancer with Accompanists, Śiva Temple, 13-14th century ce

103 Śrīśailam: Dance Panel, Śiva Temple, 13-14th century ce

104 Śrīśailam: Staff Dance, Śiva Temple, 13-14th century ce

105 Hampī: Frieze, Dancers, Throne Platform, Hazararam Temple,16thcentury ce

106 Vijayanagara: Frieze, Dancers, 16thcentury ce

Cidambaram

107-21 Dance Reliefs from Amman Walls, Devī Temple, 14th century ce

122-24 Karaṇa from East Gopuram, Naṭarāja Temple, 14th century ce

Nr̥ttamūrtis

125 Bhuvaneśvara: Gaṇeśa Mukteśvara Temple, 10th century ce

126 Halebiḍ: Gaṇeśa Hoyasaleśvara Temple, 12-13th century ce

127-28 Halebiḍ: Garuḍa with Lakṣmī–Nārāyaṇa, 12-13th century ce

129 Beḷūr: Sarasvatī, Cinnakeśava Temple, 12-13th century ce

130 Halebiḍ: Sarasvatī, Hoyasaleśvara Temple, 12-13th century ce

131 Somanāthpur:Veṇugopāla, 12-13th century ce

132 Coḷa: Bālagopāla, 12th century ce

133 Ellorā, Vākāṭaka: Śiva, Cave No. XXII, 6th century ce

134 Ellorā, Vākāṭaka: Śiva, Cave No. XV, 6th century ce

135 Gurjar Pratihāra: Śiva Dancing, 9th century ce

136 Ālamapur: Śiva, Western Cāḷukyan, 8th century ce

137 Aihoḷe Rāvaṇa Phaḍī: Western Cāḷukyan śiva, 7th century ce

138 Puṣpagiri:Śiva Dancing on Asura, 14th century ce

139 Coḷa: Śiva Dancing, 10th century ce

140 Bhubaneswar: Eastern Gaṅga: Śiva Dancing, Śiśireśvara Temple,8th century ce

141 Raichur: Śiva Dancing, 12th century ce

142 Halebiḍ: Śiva Dancing, Cennakeśava Temple, 12-13th century ce

143 Beḷūr: Śiva Dancing, Hoyasaleśvara Temple, 12-13th century ce

144 Paṭṭadakal: Śiva Dancing Virūpākṣa Temple, 8th century ce

145 Pālampeṭ: ŚivaDancing, Rāmappā Temple, 12th century ce

146 Coḷa: Naṭarāja – Bronze, 14th century ce

147 Coḷa: Naṭarāja – Bronze, 11th century ce

148 Central India: Śiva as Bhairava, 11th century ce

149 Ellorā: Śiva as Bhairava, Cave No. XXIX, Dhumar Lena,7th century ce

150 Kumbhakoṇam: Śiva Dancing, Sāraṅgapāṇi Temple, 14th century ce

151 Nepal: Viṣṇu, Vikrāntamūrti, 7th century ce

152 Kāñcīpuram: Śiva, Kailāsanātha Temple,7th century ce

153 Kāñcīpuram: Śiva as Bhairava,12th century ce

154 Central India: Śiva as Bhairava, 12th century ce

155 Tanjore: Gajasaṁhāramūrti, 11-12th century ce

Abbreviations

AD

Abhinaya-Darpaṇa

ASIR

Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report

ASR

Archaeological Survey Reports

AV

Atharvaveda

NŚ II

Gaekwad Oriental Series Second Edition Nāṭyaśāstra

BR

Bālarāmabharatam (Trivandrum Oriental Series)

HLD

Hastalakṣaṇam-Dīpīkā

HM

Hastamuktāvalī

JISOA

Journal of the Indian Society of Oriental Art

Manu

Manusmr̥ti

MG

Mirror of Gesture (by Coomaraswami and Duggirala)

NŚS

Nāṭyāśāstra Saṁgraha (Madras Oriental Series)

NŚ

Nāṭyaśāstra

R̥V

R̥gveda

SBR

Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa

SR

Saṅgītaratnākara

TL

Tāṇḍavalakṣaṇam

VD

Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa

YV

Yajurveda

System of Transliteration

vowels

अ (a)

आ (ā)

इ (i)

ई (ī)

उ (u)

ऊ (ū)

ऋ (r̥)

लृ (lr̥)

ए (e)

ऎ (ai)

ओ (o)

औ (au)

Consonants

क (ka)

ख (kha)

ग (ga)

घ (gha)

ङ (ṅa)

च (ca)

छ (cha)

ज (ja)

झ (jha)

ञ (ña)

ट(ṭa)

ठ (ṭha)

ड (ḍa)

ढ (ḍha)

ण (ṇa)

त (ta)

थ (tha)

द (da)

ध(dha)

न (na)

प (pa)

फ (pha)

ब (ba)

भ (bha)

म (ma)

य (ya)

र (ra)

ल (la)

व (va)

श (śa)

ष (ṣa)

स (sa)

ह(ha)

Anusvara (ṁ)

Visarga (ḥ)

Introduction

The present study is an attempt to investigate the nature and extent of the part played by other arts, especially literature, sculpture and music, in the development of Indian dance and to determine the role of dance in these arts. Since all classical Indian arts accept a common theory, which they faithfully follow, the attempt has necessarily involved a review of the fundamental principles of aesthetics which have governed the practice of these arts for fourteen centuries or so. Thus the scope of this presentation is:

(i) to give a general idea of the aesthetic theory common to literature, poetics, dramaturgy, sculpture, painting, music and dancing;

(ii) (a) to analyse the theory and technique of classical Indian dancing, with particular emphasis on the significance of symbols and symbolization,

(b) to trace the history of the theory of dance as formulated in the Sanskrit texts from the Nāṭyaśāstra to the Bālarāmabharatam, and

(c) to analyse the conscious attempts to represent and illustrate dance movements in sculpture, as in the Cidambaram Temple (Naṭarāja Temple);

(iii) (a)to analyse the references to dancing in the creative literature (kāvya) of Sanskrit from the early Vedic texts to the late medieval dramatic works (thirteenth-fourteenth centuries),

(b) to identify the general and more particular forms of dancing prevalent in different periods, and

(c) to establish the close relationship between dance and drama and to see how the technique of dance affects the dramatic technique of the classical drama;

(iv) (a) to analyse the treatment of the human body as form in Indian sculpture and dancing,

(b) to interpret the concepts of māna, sūtra and bhaṅga as principles of space, mass and weight manipulation,

(c) to review the yakṣī and śālabhañjikā motifs as figures representing dance movement in Indian sculpture, and

(d) to analyse the dance scenes in sculpture in terms of the technical terminology of dance as enunciated by Bharata;

(v) to trace the history of dance through pictorial evidence from the earliest murals to medieval miniature painting tradition; and

(vi) to consider the general principles of Indian musical theory and musical composition in their bearing on classical dance composition.

The sources utilized for this study are the Sanskrit texts from the R̥gvedicperiod to the fourteenth century and the examples of Indian sculpture from the earliest figurines of the Indus Valley to medieval sculpture in the field as also in collections. No attempt has been made to extend the study to the material available in regional languages.

II

The aesthetic enjoyment of the classical Indian dance is considerably hampered today by the wide gap between the dancer and the spectator. Even the accomplished dancer, in spite of his mastery of technique, may sometimes only be partially initiated in the essential qualities of the dance form and its aesthetic significance. But, in the case of the audience, only the exceptional spectator is acquainted with the language of symbols through which the artist achieves the transformation into the realm of art. The majority are somewhat baffled by a presentation which is obviously contextual and allusive but which derives from traditions to which they have no ready access. Although they are aware that the dance is an invitation, through its musical rhythms, to the world in time and, through its sculpturesque poses, to the world in space, in which the character portrayed is living, they are unable to identify themselves with him. Far less are they able to attain such identity with the dancer in his portrayal of the particular role.

Even this awareness is, however, a partial and imperfect comprehension of the essential interrelationship of the arts, which is one of the basic assumptions of classical Indian aesthetics. This interrelation, or rather this integrity, of all the arts is well illustrated by the dialogue between King Vajra and Sage Mārkaṇḍeya in the Viṣṇudharmottara Purāṇa.

King Vajra requests the sage to accept him as his disciple and teach him the art of icon-making, so that he may worship the deities in their proper forms. The sage replies that one cannot understand the principles of image-making without the knowledge of painting. The king wishes for instruction in this art and is told that, unless he is accomplished as a dancer, he cannot grasp even the rudiments of painting. The king requests that he be taught dancing, whereupon the sage replies that, without a keen sense of rhythm or a knowledge of instrumental music, proficiency in dance is impossible. Once again the king requests that he be taught these subjects; to which the sage replies that a mastery of vocal music is necessary before one can be proficient in instrumental music; and so finally the sage takes the king through all these stages before he is taught the art of iconography.

The present study is an attempt to determine the exact part played by these arts in the creation of Indian dance and in turn to ascertain the role of Indian dancing in these arts. Through the history of classical Indian sculpture and literature, it is possible to put together a fairly continuous social and technical history of dance.

III

The Hindu mind views the creative process as a means of suggesting or recreating a vision, however fleeting, of a divine truth; and regards art as a means of experiencing a state of bliss akin to the absolute state of ānanda orrelease in life (jīvanmukti). The spectator must also thus have an inner preparedness to receive this vision and be a potential artist; he is a rasika, a sahr̥daya, one who is capable of responding. The training and initiation of this person is almost as important as the training and discipline of the artist himself. All Indian arts, especially the arts of music and dancing, thus demand a trained and initiated spectator. An awareness of the salient features of the vast background of Indian dancing can help to formulate some of the demands traditionally made on the spectator. This study will, therefore, naturally concern itself with the basic aesthetic principles shared by all arts and then proceed to examine those aspects of the different Indian arts which have played an important role in the theory, technique and practice of Indian dancing.