20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Communications and Mobility is a unique, interdisciplinary look at mobility, territory, communication, and transport in the 21st century with extended case studies of three icons of this era: the mobile phone, the migrant, and the container box. * Urges scholars in media and communication to return to broader conceptions of the field that include mobility of all kinds--information, people, and commodities * Embraces perspectives from media studies, science and technology studies, sociology, media anthropology, and cultural geography * Discusses ideas of virtual and embodied mobility, network geographies, de-territorialization, sedentarism, nomadology, connectivity, containment, and exclusion * Integrates the often-neglected transport studies into contemporary communication studies and theories of globalization

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 536

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Redefining Communications

Technological Determinism and Contextualism

Techno‐Globalization: Nations and Regions

Anthropologizing Media Studies: Against EurAm‐centrism

Decentering Mediated Modernities

Cultural Presentism: Problems of History

Histories of Speed‐Up: Old Futures?

Media Centrism and the Materiality of Communications

A Reader’s Guide

Part One: The Return of Geopolitics

Part Two: Reconceptualizing Communications: Mobilities and Geographies

Part Three: The Mobility of People, Information, and Commodities: Case Studies in Communications Geography

Back to the Front …

Part I: The Return of Geopolitics

1 Communications, Transport, and Territory

Introduction

The Power of Metaphor

Passengers, Readers, Drivers, and Spectators

Communications and Geography – European and North American Traditions

Communications, Transport, and Mobilities: Intersections

Material and Virtual Networks

The Multidimensionality/Simultaneity of Complex Networks

2 Constituting Europe: Empires, Nations, and Techno‐zones

Communications and Empire: Telegraphs, Cables, and Networks

Improving Circulation: Building the Nation with Canals, Roads, and Railways

Europe as the “Pivot of History”? Constructing the Eurozone

Transporting Europeans: High Speed Networking

Eurostructures: Airports, Bridges, and Borders

Europe as Techno‐zone: The Politics of Technology

Walls and Borders: Europe’s Edges and Others

Beyond Europe: Untold Stories from the “B‐Zone”

Europe’s Troubled Prospects

Part II: Reconceptualizing Communications: Mobilities and Geographies

3 Sedentarism, Nomadology, and “New Mobilities”

Introduction

Community, Place, and Mobility: Sedentarist Metaphysics

Nomadology: Frictionless Flux?

Beyond the Sedentarist/Nomadic Binary

Migrancy as Metaphor

“New Mobilities” Theory

Mobility Systems and the History of Time–Space Compression

From the Railway System to Car System

Questions of Periodization and Determination

Historical Perspectives: How New is Mobility?

4 Disaggregating Mobilities: Zoning, Exclusion, and Containment

Introduction

Relative Mobilities and the (Continued) Friction of Distance

Transnational Mobilities: The Flow of Goods and the Control of Persons

Contained Mobility

Contemporary Borders: The Transnational Ban‐Opticon

Metaphorical and Actual Mobilities: Fast and Slow Lanes

Consigned to the Perimeters: Zoning the Nation

Aeromobilities: Above the Madding Crowd

Hierachies of Mobility and Connexity

On the Bus: The Losers’ Vehicle of Last Resort

The Politics of Waiting

Techno‐Prosthetic Mobility as a Condition of Citizenship

Visible and Invisible Geographies

5 Geography, Topography, and Topology: Networks and Infrastructures

Nearness and Farness: Geographical Proximity and Topological Connexity

The Ideology of Networks: Deterritorialization?

Liquid Geographies

Infrastructures, Discourses, and Materialities

Net Geography: Digital Districts

Network Structures and Hierarchies

Against Globalized Models: Regional and National Specificities

The Limits of Geographical Metaphors

6 The Virtual and the Actual: Being There, Disembodiment, and Deterritorialization

Being There: Questions of Place

Epistemological and Ontological Questions: Stability and Motion

The Virtual, the Material, the Actual and the Real

Questions of Mediation

Disembodiment and Representation

Net Geography and Locative Media

Virtual Trust and the “Compulsions of Proximity”

Reflexivity and Misunderstanding: Thick and Thin Modalities of Interaction

Communications: Hierarchies of Preference and Modes of Symbiosis

Teleparenting: A Test Case of Long‐Distance Relationship Maintenance

Part III: The Mobility of People, Information, and Commodities: Case Studies in Communications Geography

7 Migration: Changing Paradigms, Embodied Mobilities, and Material Practices

Introduction

1 Conceptualizing Migrancy

Migrancy as Ontological Disruption: Whose Perspective?

Assimilating, Belonging, Returning: The Case of the United Kingdom

Typologies and Archeologies of Migrancy

Place Polygamy and the “Relativization” of Community

2 Structures of Feeling: Affect and Experience

Being (In More Than One) There …

Multisite Households and “Absent Presences”

Translocal Subjectivities: Networked Feelings

Love, Loss, and Money: The Sadness of Geography

Material and Virtual Modes of Circulation

3 Migrant Perspectives: Lines of Flight

Desperate Straits

Flows of Capital, People, and Data …

Geopolitics from Below: Against Victim Perspectives

Migration, Imagination, and Ingenuity

Fortress Europe and the (Televized) Return of the Medieval Pilgrims

8 Mobile Communications and Ubiquitous Connectivity: Technologies of Transformation?

1 The Mobile Phone: Emblem of Liquid Modernity

The Powers of the Virtual: Technologies, Voices, and Publics

Technology and the Social

2 Impacts and Influences?

What Does the Mobile Phone Do?

From Technological Effects to “Affordances”

Technologies of Encapsulation and Secession

Connected Presence, Perpetual Contact: The Narrowing of Social Bonds?

3 Beyond the West

Cross‐Cultural Comparative Perspectives

Technology, Tradition, and Superstition

Third World Adaptations of the Mobile: Beyond Marginality …

Cultural Contexts of Mobility: The Particularities of Mobile Phone Use in Nomadic Cultures

4 Mobile Bodies and Mobile Technologies

The Migrant and the Mobile Phone

Migrants as Early Adopters: “Lifelines” and Budgetary Priorities

Media Logics: Mediations, Affordances, and Propensities

Medium Specificity and Media Repertoires: “Polymedia”

Virtual and Actual Proximities

9 Containerization as Globalization: The Mobility of Commodities

Introduction

1 The Box that Changed the World?

Shipping Matters: The Material Infrastructure of Globalization

From Break‐Bulk to Containerization

Invisible Infrastructures and Mobile Metaphors

Dramatizing Globalization: BBC.co.uk/thebox

A Box Becalmed in a Global Downturn …

2 The Politics of Standardization

Convergence Technologies

Standardization as Permanent Revolution?

Regional Dynamics in the Global Economy

Contradictions of Scale

Technological Innovation and Regulatory Contexts

3 Contradictions of Containerization

From Transport to Logistics

Piracy and Preemptive Securitization

The Circulation of Goods and Bads

Repurposing the Box …

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 07

Figure 7.1 Display of luggage of late nineteenth‐century immigrants to North America, Ellis Island Immigration Museum, New York 2006.

Figure 7.2 Display of luggage and bunk beds of twentieth‐century immigrants to France, Musé de la Cite Nationale de l’Histoire de l’Immigration, Paris 2009.

Chapter 08

Figure 8.1 English traditional folk dancer checks his messages, Warwick Folk Festival 2012.

Figure 8.2 Orthodox priest in virtual conversation, Crete 2016.

Chapter 09

Figure 9.1 Container boxes, Port of Los Angeles 2007.

Figure 9.2 Container ship and cranes, Port of Los Angeles 2007.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

ix

x

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

Communications and Mobility

The Migrant, the Mobile Phone, and the Container Box

David Morley

This edition first published 2017© 2017 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by law. Advice on how to obtain permission to reuse material from this title is available at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

The right of David Morley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

Registered OfficesJohn Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USAJohn Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Office9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, customer services, and more information about Wiley products visit us at www.wiley.com.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print‐on‐demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of WarrantyWhile the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the authors shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data

Names: Morley, David, 1949–, author.Title: Communications and mobility : the migrant, the mobile phone, and the container box / David Morley.Description: Hoboken, NJ : John Wiley & Sons, Inc., [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.Identifiers: LCCN 2016049318 | ISBN 9781405192019 (cloth) | ISBN 9781405192002 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781119371649 (Adobe PDF) | ISBN 9781119371625 (ePub)Subjects: LCSH: Communication–Technological innovations–History | Mass media–Technological innovations–History. | Telecommunications–Technological innovations. | Mobile communication systems. | Communication, International–History.Classification: LCC P96.T42 M67 2017 | DDC 302.23–dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016049318

Cover Image: John Stanmeyer/National Geographic CreativeCover Design: Wiley

In celebration of the indefatigable spirit of Flaubert’s multidisciplinary encyclopedists Bouvard and Pécuchet, in whose footsteps I seem to have been trudging for many years now.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments are due to the many people who helped me in different ways over the long period of this project’s gestation. In the first instance, I must thank Jayne Fargnoli both for her initial enthusiasm in commissioning the project and for keeping the faith through my long delays in delivering what I had promised. I thank the Department of Media and Communications at Goldsmiths for a valuable term’s sabbatical along the way. I also thank the many people who made helpful comments and suggestions on this material at the various institutions where I have presented talks on this project including, in the United Kingdom: Lancaster University, Manchester University, and the University of Surrey. Elsewhere: New York University; Fordham University, New York; University of California Santa Barbara; University of Southern California; NorthWestern University, Chicago; University of Wisconsin, Madison; American University in Cairo; University of Western Sydney; Melbourne University; National Chengchi and Hsinchu Universities, Taipei; University of Paris II; University of Rennes; Toulouse University; Burgos University; University of Lisbon; University of Bremen; University of Erfurt; University of Tuebingen; Charles University, Prague; University of Krakow; University of Vienna; University of Helsinki; Tampere University; Sofia University; Kadir Has and Bahcesehir Universities, Istanbul; Zagreb University; and the University of Rijeka.

The intellectual influences that shaped this book were various and included, notably, the work of the late John Urry and his colleagues in the Mobilities journal, based at Lancaster University. In my conception of migrancy, I was much influenced originally by the work of John Berger and, more recently, by that of Ursula Biemann. In relation both to the need for contextual study of technological infrastructures and to the symbolic importance of technologies, I was greatly helped by the insights of Brian Larkin’s anthropological work. In that connection, I also owe the journalist Michael Bywater a debt of gratitude for the inspiration provided by his early conception of the mobile phone as “The Ultimately Desirable Object.” My friend Dave Mason kindly provided me with the photograph of the Greek priest communicating with the virtual world at the beginning of Chapter 8. The late Alan Sekula was one of those who first brought my attention to the world of containerized transport and was also the person who arranged the tour of the port of Los Angeles that allowed me to take the photographs accompanying Chapter 9. I owe Dick Hebdige gratitude for inviting me to UCSB’s path‐breaking conference on “The Travelling Box” in 2007, and I thank Jeremy Hillman for kindly agreeing to be interviewed about his work on the BBC’s “Box” project.

I should also like to thank my daughter Alice for her ingenuity and resourcefulness in finding my cover image for me when I could not locate it myself. Lastly, though very far from least, I am grateful to CB, not only for her (eternally observant) detective work, which first alerted me to the existence of the BBC “Box” but also for her patience in chewing these matters over with me so frequently, often on the way both to and from Old Milverton.

Beyond all that, I am also grateful to the designers of the computer software that enabled the book to be produced (as it was) by dictation, once I could no longer easily use a computer keyboard. But this is a double‐edged sword, and in this connection, I must also offer a “Reader Alert”: this type of software inevitably introduces a certain level of unpredictable error in transcription, which (lacking any “QWERTY”‐style logic) no amount of proofreading can guarantee to eliminate. Thus, alongside any conceptual errors and factual inaccuracies that still remain in the text, the reader may also find instances of pure nonsense. I would of course, prefer to attribute them entirely to the technology, were that not to fall into technological determinism.

Introduction: Redefining Communications

The book before you covers a wide range of topics only some of which will be familiar to media and communications scholars. It is a synthetic text that aims to bring together perspectives from media studies, science and technology studies, transport studies, sociology, and cultural geography on questions of mobility, territory, communication, and transport in the contemporary world. It is, by intention, programmatic and often takes an exhortatory tone: my objective is to persuade the reader that a number of critical issues in the field of contemporary culture and politics will be better understood if this broader interdisciplinary perspective is brought to bear on the questions at stake. To this end, the text is replete with indicative examples from a variety of fields, by means of which I hope to demonstrate the kind of benefits to be had from the perspective on offer here.

As is explained at more length in Chapter 1, my ambition is to redefine the agenda of media and communications studies and, in particular, to (re)expand the definition of communications so as to once again include within it (as was historically the case) the realms of material mobility, transport, and geography. Thus, in many places, I invoke the phraseology of geopolitics, power, and territory – although of course, the territories of concern are now both material and virtual, online and off. Against the utopian futurism of much research in the field, which focuses primarily on the virtual, I am concerned to restore the material dimension to the analysis by considering how these two dimensions of geography are now articulated with each other in increasingly complex modes of symbiosis.

By way of establishing a broader theoretical framework within which the book’s particular arguments can be understood, I spell out below some of the presumptions, commitments and perspectives which have guided its writing.

To some extent, my approach can be defined negatively in terms of the critiques of Mediacentrism, Eurocentrism, and Cultural Presentism, which I have articulated elsewhere.1 More positively, I am concerned to bring together the European and North American materialist traditions of communications theory represented by Armand Mattelart, Yves de la Haye, Harold Innis, James Carey, and John Durham Peters2 in combination with perspectives offered by the “new mobilities” paradigm,3 alongside work in transnational studies,4 cultural geography,5 and transport studies.6 To put it polemically, my approach represents the opposite of what I regard as the technologically determinist forms of “new media” theory as represented by the work of scholars such as Freidrich Kittler, Scott Lash, and Lev Manovich.7 Let me now explicate that set of perspectives a little more fully before proceeding to the more particular agenda of the book’s later chapters.

Technological Determinism and Contextualism

We are often told that, under the impact of the new technologies of our globalized age, we live in an increasingly borderless world characterized by unprecedented rates of technological change and mobility, and new modes of time–space compression. In many versions of the story of globalization, we are offered an abstracted sociology of the postmodern, inhabited by an uninterrogated “we,” who “nowadays” live in an undifferentiated global world, whose lives are increasingly determined by the (seemingly automatic) effects of the new media. However, the technologically determinist nature of these claims flies in the face of a great deal of audience research since the mid‐1980s, which has demonstrated the complex and variable ways in which media technologies are interpreted and mobilized by their users. My own view is that, rather than accepting these generalizing and abstracted approaches, we need to understand how a variety of media technologies, both new and old, are fitted into, and come to function within, different cultural contexts.

That kind of “contextualist” approach to questions of technological change is defined by Jennifer Bryce as one in which, rather than starting with the internal “essence” of a technology and then attempting to deduce its “effects” from its technical specifications, one begins with an analysis of the interactional system in a particular context and then investigates how any particular technology is fitted into it.8 Clearly, while particular technologies do each have their own specific capacities and affordances, no technology has straightforward impacts – not least because one has to begin with the question of which people (differentially) see the potential relevance of any given technology and how they might use it in the specific cultural context of their own lives. This is to argue that context is no “optional extra,” which we might study at the end of the analytic process, but rather, is best seen a “starting point” – which has determining effects on both production and consumption.9 Thus, rather than focusing on digitalization or cyberspace in the abstract, we might better examine the particular types of cyberspaces that are instituted in specific localities under particular cultural, economic, and political circumstances. In saying this, evidently, I follow the lead originally given by Raymond Williams in his study of how the development of television technology was influenced by the contexts in which it operated.10 In arguing thus, I also follow the example set by Danny Miller and Don Slater’s study of the Internet in Trinidad – as a way of understanding how the worlds of the virtual and the actual are differently integrated in a specific context.11

None of this is to argue that the specific capacities and affordances of a given technology or infrastructure are either unimportant or inconsequential. Much of what follows – whether in the discussion of transport infrastructures in Part One or of the various technologies of containment in Part Two or in relation to the mobile phone and the container box in Part Three – is precisely concerned to develop a more nuanced analysis of their respective and particular powers. The question, for me, is how to understand the operation (and limits) of these powers as they are instantiated in particular circumstances. Following de Certeau, I take the view that the most illuminating moment is often that at which the strategies of powerful agents, institutions, and their technologies are in tension with the tactics of those whom they hope to control, who have to “make do” by choosing from the particular menu of technologies on offer to them and mobilizing these resources to their own purposes as best they can.12 The outcome in each case has to be considered in the particular as the balance of power varies between different instances – and thus the result of the encounter is by no means always predictable.

Techno‐Globalization: Nations and Regions

Coming from a cultural studies tradition which prioritizes grounded theory and emphasizes specificity, I am unsympathetic to abstracted “One‐Size‐Fits‐All” analyses of globalization‐through‐technology, which reduce the whole of history to one Big Story of deterritorialization and cultural homogenization. Here, we may perhaps be better served by some differentiations between the perspectives of a variety of different regions, nations, and periods. Nonetheless, the discourses of techno‐globalism continue to repeat the claim that nations are (somehow) about to disappear as a result of the advance of new technologies. However, Kai Hafez rightly warns of the dangers of exaggerating the degree to which media globalization has, in fact, taken place and questions the idea that there is any simple, linear process of transnationalization in the media.13 He also insists that we attend to the continuing significance of national or regional boundaries in the effective constitution of media markets – both old and new. Thus, not only television (especially in its news‐based modalities) but also a great deal of Internet traffic still flows within, rather than across, cultural and linguistic boundaries. Such boundaries, and their political manifestations, continue to be of great significance, globalization notwithstanding. Similarly, if you consult the Facebook app on “Facebook Stories” you can readily see how the structure and patterning of Internet “friending” runs along the very predictably restricted paths laid down by national, cultural, linguistic, and political boundaries.14

Anthropologizing Media Studies: Against EurAm‐centrism

These issues also have to be considered alongside the problem of media and communications studies’ continuing EurAm‐centrism.15 Here, the difficulties are several. As authors such as John Downing and Brian Larkin have argued, most of these theories have drawn their template from the particular techno‐cultural conditions of the white, middle‐class, Euro‐American world – what has also been called the “WEIRD” word – not just statistically abnormal but more specifically White, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and (more or less) Democratic. The problem is that they have often been imported wholesale and applied elsewhere without being appropriately tailored to the local situation.16 From a perspective beyond the North Atlantic this means that media studies increasingly appears parochial because of its failure to recognize the specificity of its own history.17

We thus need to develop a more internationally comparative perspective, but if the benchmark from which we start is always that of a Western perspective (to which all other instances are merely treated as supplementary, or even exotic) then the problem of ethnocentricity remains unresolved. The simple addition of “deviations” from a Western norm cannot satisfactorily remedy this fundamental epistemological problem. In this context, some anthropological perspectives may be of assistance. The new millenium has seen a welcome increase in work which brings specifically anthropological perspectives on culture into discussions of media, and what unites this work is its insistent relativization of all cultural certainties.18

Decentering Mediated Modernities

The necessary scale of the relativization at stake here is daunting – not least because discussions of media and communications inevitably presume as their backdrop a variety of strong (and again usually EurAmcentric) presumptions about the nature of modernity – and of its central institutions, such as the city. In the world’s rich Northwest, we tend to think of cities in terms of their size and wealth, and of them necessarily having particular facilities and infrastructures (such as municipal transport and sewage systems). However, empirically speaking, most of the world’s fastest growing cities, all of which are relatively poor, have none of these conventional attributes. Growth in cities like Mumbai and Lagos is occurring without widespread industrialization, infrastructure provision, or formal job creation. These are places that “invert every essential characteristic of the so‐called modern city.” They are not “catching up” with the West: rather, they challenge us to rethink what a “modern” city is, or may become.19

In this same spirit, Brian Larkin’s study of emergent media cultures in northern Nigeria (which forms a significant background to my later discussion of these issues in Chapter 8 in relation to the mobile phone) begins by asking what media theory would look like if it began from how the media actually work in a place like the contemporary Nigerian city of Kano. Thus he very deliberately places Nigerian media in the context of the particular types of institutions, infrastructures, technologies, cosmologies, and conceptions of selfhood available there.20 Larkin’s aim is thus to defamiliarize Western presumptions and productively “interrupt” our taken‐for‐granted approaches, insofar as they assume the universal normality of the sociopolitical configurations of the West, by providing us with a kind of negative mirror in which we might see our own taken‐for‐granted practices in a “denaturalized” light.21

In developing my arguments in the succeeding chapters, I follow Doreen Massey by insisting that, in the worlds of the media as elsewhere, we must attend to geographical, regional, and spatial variability. However, this is not to reduce geography to a concern with the merely local, the empirical, and the a‐theoretical but, rather, to recognize, with her, that there is nothing “mere” about the local. “Spatializing” media theory means recognizing its multiplicity and its openness. As Massey observes, the recognition of spatial multiplicities is a precondition for the recognition of temporal openness, so as to literally “make space” for other stories of the future.22

Cultural Presentism: Problems of History

However, as Lynn Spigel has put it, the more we speak of futurology, the more we need also to place contemporary changes in a historical perspective.23 The problem here is that much of media and communication studies, as presently constituted, suffers from a drastically foreshortened historical perspective and thus displays a form of what Graham Murdock and Michael Pickering call “cultural presentism.”24 In an era of new modes of digitalization, technical convergence, and individualized and interactive media systems, it becomes all the more urgent that we place all these issues in a more effective historical frame. Happily, there are some signs of this deficiency now being made good. Siegfried Zielinski’s path‐breaking work on what he calls the “deep time” of media history has already helpfully recontextualized the particular developments of cinema and television as what he calls mere “entr’actes” in a much longer history of audiovisual media.25 Ultimately, as demonstrated in Barbara Stafford and Frances Turpak’s book on the Getty Museum’s (2001) “Devices of Wonder” exhibition, all this involves a very long history. There are continuities here which can usefully be traced back to the worlds of the “magic mirror” and the portable Wunderkabinett (the precursor to today’s laptop or tablet?), as well as to the worlds of the automaton, the magic lantern, and the camera obscura.26 In the recent period, the development of what has come to be called “media archaeology” has now begun to turn this historicizing perspective on a variety of aspects of media research that previously lacked the benefit of the relativization it helpfully brings to any infatuation with the charms of the present.27

Histories of Speed‐Up: Old Futures?

We are often told that we are entering a new historical epoch, in which change takes place at an ever increasing rate as result of the effects of increasingly powerful technologies.28 However, it can perfectly well be argued that we live in an age of technological stasis, relatively speaking, compared with the speed of technological change in the late nineteenth century (the era of the invention of radio, the cinema, photography, the steamship, the railroad, and the airplane). In relation to the changing mobility patterns discussed in Part Two of the book, Steven Kern’s analysis of the culture of time and space in the late nineteenth century shows that, in proportional terms, the increase in numbers of people travelling and the distances they travelled then was far more radical a change than anything experienced in recent years. We shall return to those issues in more detail in Chapter 3.29

Speaking of the (relatively) unchanging nature of quotidian routines in much of the rich West, the journalist Simon Jenkins observes that he still shaves with soap and razor, dons clothes of cloth and wool, reads a newspaper, drinks coffee heated by gas or electricity, and goes to work with the aid of a petrol and internal combustion engine to a centrally heated office, where he types on a QWERTY keyboard.30 As he notes, none of these activities has altered significantly during the past century, whereas in the previous hundred years, the pattern of daily life altered beyond recognition. Similarly, in relation to the contemporary notion of our living in a digital age, Tom Standage rightly insists that its commencement must be dated at least from the moment in the mid‐nineteenth century, when the telegraph – as the first technology to reduce all information to a binary code – was invented.31

These issues also bring us to the eternally vexed question of how to address the question of periodization in our work. Just as Raymond Williams noted the coexistence of residual, dominant, and emergent tendencies within any one historical period, Fernand Braudel always insisted on the need to recognize the simultaneous existence of different temporalities and Bruno Latour argues that “modern time,” in any pure form, has never existed and we inevitably live amidst a jumble of technological eras.32

To turn to the currently available visions of the techno‐future, Richard Barbrook observes that the imaginary of technological futurism is curiously static, and that the vision of high‐tech utopia offered to us in the early twenty‐first century is curiously similar to that which could have been seen at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.33 At stake in these contemporary discourses of what Vincent Mosco calls “cyberbole” is the tendency to see that future as the pure extension of logic, technical rationality, and linear progress. As we shall see further, in Chapter 5, technologies of different eras have, in their turn, often evoked the same vision of “redemption.”34

The further problem here is that scholars have tended to focus exclusively on technological novelty, while in reality, it is older technologies that continue to dominate our lives. Moreover, our accounts of technology are fundamentally unbalanced by a propensity for focusing on invention over use, acquisition over maintenance, and inevitability over choice35 yet what matters more is how technologies are used and by whom – and how they are transformed and “reinvented” in hybrid or creole forms as their use shifts from one context to another.

Thinking about the history of technology‐in‐use – and concentrating on the adaptation, operation, and maintenance of things – offers us a very different perspective from that of the innovation‐centered model. Most importantly, it offers us a global history, by means of which, as Edgerton argues, we can shift our attention away from the large‐scale, spectacular, masculine, prestigious technologies of the rich white world, to also bring into focus the small‐scale, mundane, feminized, and often creolized technologies of the bidonvilles and shanty towns of the world.36 These will often involve adaptations of older, imported technologies that are given a new lease of life and adapted for local use (such as the tin drum, flattened into a roof or wall in a Brazilian favela or the scooter crossed with the rickshaw to produce the tuk‐tuk taxis of Thailand). These technologies are at the heart of the fastest growing cities, such as Lagos and Mumbai – the places where, as I noted earlier, the modernities of the future are already taking shape.

Media Centrism and the Materiality of Communications

Having outlined my theoretical concerns in relation to the general issues which frame the contents of the chapters that follow, I now turn to the question of media centrism. I have detailed elsewhere my reservations about the improperly media‐centric nature of communication studies.37 Much of the rest of this book consists of an attempt to outline what a non media‐centric approach would look like – mobilizing an expanded notion of communications, including its material dimensions. In relation to the latter issue, my argument can perhaps usefully be read in the context of what has been called the recent “materialist turn” in communications studies. For my own part, it was coming across the late Alan Sekula’s militant denunciation of the largely unquestioned (even if erroneous) belief that, as he put it, e‐mail and air travel were the main bases of globalization that set me on this track. It was his work on the central role of container shipping as the fundamental “enabling condition” of trade in the global economy that provided the original inspiration for the analysis developed in Chapter 9. This emphasis on materiality and infrastructure can also be seen in the more recent “materialist turn” in the field, reflected in the work of scholars such as Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, among others.38

A Reader’s Guide

In terms of structure, this book is divided into three parts: the first sets out the theoretical and conceptual agenda of the approach that I am advocating and focuses on the role of communications and transport technologies in the constitution of communities at different scales. The second reframes the concerns of media studies within the broader context of the new forms of mobility – and of (virtual) geography – which are held to characterize the contemporary world. The third offers a set of case studies demonstrating how the perspectives outlined above may help us to develop a better understanding of three figures that I have chosen as emblematic of our era – the migrant, the mobile phone, and the container box.

However, I must also enter a caution here about the claims I make for my argument. Given the gargantuan scale and range of the topics the book covers, I have had to restrict, for the sake of brevity, any ambitions to be exhaustive in my approach to the particular specialist subfields which I survey. My examples and case studies can thus be no more than indicative, rather than conclusive. Moreover, as I weave the arguments together around a set of recurring themes focused on the different forms of articulation of virtual and material geographies, I inevitably run the risk of some repetition in my attempts to demonstrate the virtues of a multidimensional perspective on any one issue. Whether the game is worth the candle is, ultimately, for the reader to judge.39

Part One: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 1, “Communications, Transport, and Territory,” begins by outlining the problems that have arisen as a result of the gradual shrinking of the meaning of “communications” to include only its rhetorical and discursive dimensions. It goes on to make the case for restoring the broken link between the analysis of symbolic and physical modes of communication, including the material forms of transport and mobility. In all of this, my further intention is to go beyond the social sciences’ conventionally “a‐mobile” perspective (usually limited to the territory of a given nation‐state) while offering an approach to transport and mobility that, so as to better address their sociocultural and political dimensions, transcends questions of mere economic functionality.

Chapter 2, “Constituting Europe: Empires, Nations, and Techno‐zones,” addresses the role of communications and transport technologies in the constitution of communities. Here, we attend specifically to their role in enabling power to be operationalized across increasingly greater distances in the process of the formation of both nations and empires in Europe. Central here are the arguments initially developed by the “physiocrats” of eighteenth‐century France about the crucial role of transport systems in enabling “free circulation” and thus ensuring the economic health of the nation – arguments with a strong contemporary resonance. Beyond these historical examples, I end the chapter by focusing on the contemporary construction of the European Union as a transnational community, or in Andrew Barry’s terms a “techno‐zone”40 based on specific practices of community building and border control, in relation to questions of trade, technology, and demography.

Part Two: Reconceptualizing Communications: Mobilities and Geographies

Chapter 3, “Sedentarism, Nomadology, and ‘New Mobilities’ ,” is principally concerned with exploring the potential of the “new mobilities” paradigm for reconceptualizing the study of communications in terms of the historical evolution of mobility systems.41 These issues are contextualized by reference to debates about conceptions of community, place, and mobility, and I propose an approach that aims to transcend the sterile opposition often posed between nomadological and sedentarist perspectives on these topics. It goes on to critique conventional histories of the field, which often produce a simplistic narrative, principally focused on the continual increase in technologically enabled speed.42 The chapter explores a variety of historical periodizations of mobility – and the extent to which the technologies of each era produce a given mode of subjectivity. It also reconsiders claims about the “newness” of contemporary mobilities in the context of evidence about earlier periods of time–space compression and globalization, especially in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

As its title, “Disaggregating Mobilities: Zoning, Exclusion, and Containment,” indicates, Chapter 4 is concerned to move beyond the abstract metaphysics of mobility to disaggregate its different forms. This involves distinguishing between the mobility enjoyed by different categories of persons as well as the disjunctions between the increasing fluidity in the global flow of goods on the one hand and the increasing modes of control exercised over (certain types of) population movements on the other. Thus we focus here on the changing forms of material and virtual borders; on mobility hierarchies and relative speeds of mobility; on the politics of waiting; and on the various modes of surveillance, exclusion, and containment applied to the mobility of differently categorized persons and entities.

Chapter 5, “Geography, Topography and Topology: Networks and Infrastructures,” focuses on the new forms of “philosophical geography”43 that have emerged with the development of networked forms of techno‐connectivity. The issue of geographical proximity is often now argued to have been displaced by that of topological connexity, so that absolute space or distance becomes less important than the linkages made through various forms of networked virtuality. The chapter recontextualizes arguments concerning networking as a form of “deterritorialization” by placing them in a historical perspective, by recognizing that the ideology of “salvation through networks” is no new phenomenon. It reviews the emergence of “liquid geographies” and also addresses the continuing significance of material infrastructures.44 It further examines the specific geography of the Internet, itself manifest in phenomena such as “digital districts” – in which the “new technology” companies of our day are, in fact, found to cluster in very particular geographical locations. It also examines the extent to which, rather than demonstrating a flat or rhizomic structure, these virtual worlds increasingly display similar forms of hierarchy to those familiar from previous cultural industries, with a small number of large companies controlling a high proportion of virtual activity.

Chapter 6, “The Virtual and the Actual: Being There, Disembodiment, and Deterritorialization,” offers an analysis of contemporary debates about the changing relationship of virtual and actual geographies. It addresses the history of communications technologies with the capacity to transform material absence (or distance) into virtual presence and focuses on debates about the capacity of contemporary digital technologies to provide us with an experience of “place polygamy.” These technologies are often argued to “dissembed” us thereby from the material world of physical geography. However, I offer here a perspective that, while recognizing the significance of the new electronic landscapes in which we live,45 is skeptical of arguments about the “place‐annihilating” capacities of communications technologies.46 Here we explore the increasing interdependence of virtual and actual geographies, as exemplified by the development of the “locative media” of today’s geospatial web. The chapter also addresses the capacities (and limitations) of differently mediated modes of communication in relation to the continuing “compulsions” of physical proximity and the uncertainties of virtual forms of trust.47

Part Three: The Mobility of People, Information, and Commodities: Case Studies in Communications Geography

Chapter 7, “Migration: Changing Paradigms, Embodied Mobilities, and Material Practices,” addresses the archaeology of the changing modes (and typologies) of historical and contemporary migrancy as a differentiated set of material practices developed in varying contexts and constituting a variety of complex new “ethnoscapes,” in Arjun Appadurai’s terminology.48 Here we explore questions related to the development of multisited households and diasporic networks and also the experience of ongoing “place‐polygamy” and trans‐local subjectivities on the part of a growing number of migrants. The chapter revisits some of the concerns of my earlier work on the ontological crisis that migrancy often presents for “host” countries,49 all of which has been given a new significance in the context of recent crises around refugee and asylum seekers in Europe and the Middle East. It further discusses how, in the specific case of the United Kingdom, the division between those who consider themselves part of that community and those deemed to be illegitimate “outsiders” is now being redrawn on grounds other than the familiar ones of race and ethnicity. The chapter also offers a perspective on “geopolitics from below” addressing these issues from the point of view of would‐be migrants themselves. Thus it also focuses on the forms of ingenuity and resourcefulness developed in the informal economy that supports the practice of long‐distance migrancy. In this context, we shall consider the various routes (and blockages) in the “lines of flight” along which flows of capital, data, commodities, and migrants all travel, though at very different speeds. Taking the specific case of African migrancy, we consider the situation of those attempting to cross the “Desperate Straits,” which separate North Africa from Europe. Following Ursula Biemann’s attempt to reverse the usual “victim perspectives,” in which migrants are only shown at the moment of their capture (or failure), we also investigate the complex routes by which sub‐Saharan migrants are guided across the deserts to the North African coast by Tuareg nomads mobilizing an ingenious combination of traditional desert navigational skills and the latest in GPS and four‐wheel‐drive technology.50

Chapter 8, “Mobile Communications and Ubiquitous Connectivity: Technologies of Transformation?,” focuses on the debates about the transformative powers of mobile telephony.51 Here, I treat the mobile phone as a heuristic device around which important debates about the culture and politics of our era are now condensed. In this respect, the “mobile” has perhaps become one of the “emblematic” technologies of our age – just as the motor car and the television set were emblematic of previous eras. Here I address the affordances offered by the mobile phone, paying particular attention to its potential roles (along with other mobile ICTs) as a democratic device capable of empowering and giving voice to the dispossessed in moments of political stuggle. Conversely, I also address its potential role, in other contexts, as a “secessionary” or “capsular” technology with a tendency to reinforce the narrowing of social bonds.52 I argue that we need to understand the mobile phone not in terms of any technological “essence” but in terms of its place within the overall repertoire of “inconspicuous but omnipresent” technologies of mediation that now surround us.53 Building on the earlier critique of Eurocentrism, the chapter then examines, from a “contextualist” point of view, how the mobile phone has developed in parts of the world where the social, demographic, technological, political, and infrastructural assumptions of the rich Northwest simply do not apply. Here we shall address some of the “adaptations” of the mobile phone among the poor of the Third World and its significance when inserted into nomadic or religious, rather than sedentary or secular societies.

By way of better articulating the concerns of chapters 7 and 8, in the conclusion to this chapter, I turn to the question of the specific functions of mobile telephony in the world of migrants – with whose lives, as “mobility pioneers,” the mobile phone has been claimed to share a significant “elective affinity.” Here we attend to the growing significance of multisite households and translocal subjectivities in the migrant experience, as well as to the particular significance of mobile forms of communication as the “social glue” that holds together migrants and their families.54

Chapter 9, “Containerization as Globalization: The Mobility of Commodities,” takes as its starting point Alan Sekula’s critique of “idealist” perspectives on globalization that ignore the material foundation of the global economy – the transport of material goods across the world’s oceans.55 The chapter focuses on how much the mobility of objects in commodity form has been transformed by the technology of containerization.56 In examining the contentious history of “standardization” in the development of the (transmodal) container box, we also discover an illuminating “pre‐echo” of contemporary debates about (cross‐platform) digital convergence technology in the media field and communications. By attending to the material practices underpinning these transport systems (and the unresolved tensions and contradictions within them), we may better avoid any abstracted or dematerialized perspectives on globalization. The container box itself is increasingly recognized as one of the central symbols of our era, and its story is dramatized here by means of an account of the BBC’s “Box” project. In that case, the journey of one particular container box around the world was used to provide a multiplatform narrative about the multimodal transport system on which we now all depend so much. The chapter goes on to develop a critical perspective on the significance of the fast‐growing logistics industry, which has come to be so important in the recent period, as a way of managing the complex long‐distance supply chains that now link the different parts of the global economy. In this context we also consider the significance of the recent rise of various forms of (hi‐tech) sea‐borne piracy and the effects on global shipping of the “securitization” strategies that have been deployed as desperate, and thus far, only partially successful, attempts to combat them.

In conclusion, the chapter also queries the conventional story of the container box as a necessarily transformative technology by examining the extent to which the standardization process has itself always been contradictory and contested – and thus never universally instantiated. We also have to recognize the wide range of uses for which the container box has been repurposed in different parts of the globe, as it now functions not only as a container for travelling commodities but also, in different contexts, as a form of temporary shelter, of low‐cost‐housing, and as one of the “building blocks” of military encampments, prisons, educational institutions, and large‐scale markets across the globe. Thus, we end the story of the “box” by exploring the multiple purposes to which it is now put in different places.

Back to the Front …

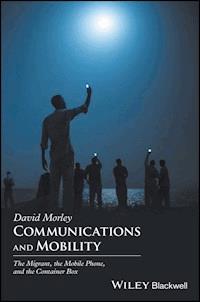

By way of bringing these introductory remarks to a (temporary) conclusion, let me refer back to the image on the cover, which brings together many of the key themes of the book. In the photograph, we see a group of illegal migrants who were being smuggled by ship and had been temporarily left to themselves on a beach – at which point, they all seized the opportunity to point their mobile phones towards the sky (as if in some ritualistic form of supplication) in the hope getting a phone signal, perhaps so that they could communicate with their families back home, or maybe with those awaiting them at the end of the next stage of their journey. The ship from which they had disembarked is hidden, off‐screen, as this poignant little scene is enacted.

However, beyond the micropolitics of the personal dramas at stake here, there are also geopolitical issues in play: the beach itself is in Djibouti, at the narrow Bab el Mandeb Straits, on the Gulf of Aden. This is one of the key geopolitical “pinchpoints” in global trade through which sail a vast proportion of the world’s container ships. Indeed 30 percent of all shipping, worldwide, passes through here, en route to and from the Suez Canal. In recent years Djibouti’s strategic importance has been boosted further, as it has now become an important base for international “anti‐piracy” strategies, involving not only France (as Djibouti’s ex‐colonial master) but also Germany and Japan, alongside America, for whom it is central to their antiterrorism strategy. At the time of writing (May 2016), as part of their new “active defence” strategy, the Chinese government has decided effectively to contest the long‐standing American dominance of the Gulf by building its own militarized port directly across from what is already America’s largest military outpost in Africa, thus transforming the straits into a major potential fault line in any future conflict over world trade.57

Notes

1

D. Morley (2009) For a Materialist, Non Media‐Centric Media Studies,

Television and New Media

10

(1) ; and D. Morley (2012) Television,

Technology and Culture: A Contextualist Approach, Communication Review

15

.

2

A. Mattelart (1996)

The Invention of Communication

, University of Minnesota Press; Y. de la Haye (1979)

Marx and Engels On the Means of Communication

, International General; H. Innis (1950)

Empire and Communications

, Oxford University Press; J. Carey (1989)

Communication as Culture

, Unwin Hyman; J.D. Peters (1999)

Speaking into the Air

, University of Chicago Press.

3

This paradigm has been developed in the work of the

Mobilities

Journal launched in 2006.

4

A. Appadurai (1996)

Modernity at Large

, University of Minnesota Press.

5

T. Cresswell (2006)

On the Move

, Routledge.

6

R. Knowles, J. Shaw, and I. Docherty (eds.) (2008)

Transport Geographies

, Blackwell.

7

F. Kittler (1999)

Gramophone, Film, Typewriter

, Stanford University Press; Scott Lash (1994)

Economies of Signs and Spaces

, Sage; and L. Manovich (2002)

The Language of New Media

, MIT Press.

8

J. Bryce (1987) Family Time and Television Use, in T. Lindlof (ed.),

Natural Audiences

, Ablex Books.

9

This emphasis is similar to that of the “circuit of culture” model developed by Stuart Hall and his colleagues at the Open University – see P. du Gay, S. Hall, L. James, et al. (1996)

Doing Cultural Studies

Open University Press.

10

See R. Williams (1974)

Television

, Technology and Cultural Form, Fontana Books. See also the work of the subsequent scholars associated with the “social shaping of technology” approach, D. Mckenzie and J. Wajcman (eds.) (1999)

The Social Shaping of Technology

, Open University Press. For a critique of that approach, see among others M. Lister, J. Dovey, S. Giddings, et al. (2008)

The New Media: A Critical Introduction

, Routledge.

11

D. Miller and D. Slater (2000)

The Internet: An Ethnographic Approach

, Berg, London.

12

M. de Certeau (1984)

The Practice of Everyday Life

, University of California Press.

13

K. Hafez (2007)

The Myth of Media Globalisation

, Polity Press.

14

Facebook app at

www.facebookstories.com/stories

.

15

The term “EurAm” appeared in Japan in the 1980s and 1990s and reflects the lack of distinction between the cultures from the Japanese perspective. See D. Morley and K. Robins (1995)

Spaces of Identity

, Routledge, Ch. 8.

16

J. Downing (2005)

Internationalising Media Theory

, Sage; B. Larkin (2008)

Signal and Noise Media, Infrastructure and Urban Culture in Nigeria

, Duke University Press; J. Diamond (2013)

The World Until Yesterday

, Penguin. On these issues cf. also J. Curran and M.‐J. Park (eds.) (2000)

De‐Westernising Media Studies

, Routledge.

17

In this context Georgette Wang argues that, to take a key example, Habermas’ conception of the public sphere, having been coined to describe a particular discursive space within eighteenth‐century Europe, cannot simply be transposed to other locations, with different political and cultural histories, without considerable modification G. Wang (2011) After the Fall of the Tower of Babel, in

De‐Westernising Communication Research

, Routledge.

18

Cf. the collections by K. Askew and R. Wilk (eds.) (2002)

The Anthropology of Media

, Blackwell; F. Ginsburg, L. Abu‐Lughod, and B. Larkin (eds.) (2002)

Media Worlds

, University of California Press; J.X. Inda and R. Rosaldo (eds.) (2002)

The Anthropology of Globalisation

, Blackwell; E. Rothenbuhler and M. Coman (eds.) (2005)

Media Anthropology

, Sage.

19

R. Koolhaas et al. (eds.) (2004)

Mutations

, Actar Publications.

20

Larkin,

Signal and Noise

; cf. also P. Mankekar (2015)

Unsettling India: Affect, Temporality, Transnationality

, Duke University Press.

21

Cf. A. Abbas and J. Erni (eds.) (2005) Introduction, in

Internationalising Cultural Studies

, Blackwell.

22

D. Massey (1994)

Space, Place and Gender

, Polity Press; D. Massey (2005)

For Space

, Sage.

23

L. Spigel (2004) Introduction, in L. Spigel and J. Olsson (eds.),

Television After TV

, Duke University Press.

24

G. Murdock and M. Pickering (2009) The Birth of Distance, in M. Bailey (ed.),

Narrating Media History

, Routledge.

25

S. Zielinski (1999)

Audiovisions: Cinema and Television as Entr’actes in History

, University of Amsterdam Press; S. Zielinski (2008)

The Deep Time of the Media: Towards an Archeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means

, MIT Press.

26

B. Stafford and F. Terpak (2001)

Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen

Getty Institute.

27

J. Parikka (ed.) (2011)

MediaNatures

, Open Humanities Press; J. Parikka (2012)

What is Media Archeology?

Polity Press.

28

Cf. D. Edgerton (2006)

The Shock of the Old

, Profile Books.

29

S. Kern (2003)

The Culture of Time and Space 1880–1918

, Harvard University Press. The Economist Ha‐Joon Chang makes the point quite literally: as he observes, the invention of the telegraph reduced the time that it took to carry a message across the Atlantic from two weeks to 2 minutes, a quite spectacular reduction, by a quite spectacular reduction, by a factor of approximately 1000. Conversely, insofar as the Internet has reduced the time of sending a page of text from the 10 seconds needed by a fax machine down to one second (or a fraction thereof) that is a far less significant reduction of a factor of only around 10%. H.‐J. Chen (2010) The Net Isn’t as Important as We Think,

The Observer New Review

(August 29).

30

S. Jenkins (2007) The Age of Technological Revolution is 100 Years Dead,

The Guardian

(January 24).

31

T. Standage (1998)

The Victorian Internet

, Walker and Co. Amazon and eBay may have speeded up earlier forms of long‐distance retailing – such as the kind of catalog‐based, mail‐order systems of postal shopping familiar in the industrialized West in the 1960s – but they certainly did not invent it. As far back as the mid‐nineteenth century, the Sears Roebuck catalog made a cornucopia of consumer goods available to farmers in isolated rural homesteads across North America who had never previously been able to acquire them at all. In historical terms, so far as the development of consumer cultures goes, the implementation of that system, 150 years ago, was a far more revolutionary innovation than that achieved in recent years by Amazon.

32

R. Williams (1965)

The Long Revolution

, Penguin; Williams,

Television Technology and Cultural Form

; F. Braudel (1995)

A History of Civilisations

, Penguin; B. Latour (1993)

We Have Never Been Modern

, Harvester Wheatsheaf.

33

R. Barbrook (2007)

Imaginary Futures

, Pluto Press.

34

V. Mosco (2004)

The Digital Sublime

, MIT Press. A. Mattelart (2000)

Networking the World

, University of Minnesota Press.

35

Cf. B. Winston (2005)

Media, Technology and Society

, Routledge.

36

Edgerton,

Shock of the Old

, pp. xi–xiii; cf. also P. Oliver (2003)

Dwellings: The Vernacular House Worldwide

, Phaidon Books; P. Chamoiseaux (1997)

Texaco

, Granta Books.

37

Morley, For a Materialist.

38

See A. Sekula (1996)

Fish Story

, Richter Verlag; see also his “essay‐films”: A. Sekula (2006)

The Lottery of the Sea

, Icarus Films; N. Burch and A. Sekula (2010)

The Forgotten Space

, Doc.Eye Film with WildArt Film. On the “materialist turn” see L. Parks (2005)

Cultures in Orbit: Satellites and the Televisual

, Duke University Press; L. Parks and N. Starosielski (eds.) (2014)

Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures

, University of Illinois Press; N. Starosielski (2015)

The Undersea Network

: Duke University Press.

39

In this context I have to acknowledge, in passing, my somewhat inadvertent role models – Gustave Flaubert’s mythical scribes Bouvard and Pécuchet, who, rather in the spirit of Diderot’s great enterprise of the “Encyclopedie,” set out to master the full range of disciplines necessary to understand the world. Of course, they end up in a comedy of disillusionment with the inevitable limitations of all forms of knowledge, overwhelmed by unsolvable intellectual complexities and reduced to the role of pessimistic scribes with the impossible task of copying out everything that is already known. There were certainly times, when writing this book, when I had a strong sense that I knew just how they felt. (G. Flaubert (1954)

Bouvard and Pécuchet

, New Directions, with an introduction by Lionel Trilling.)

40

A. Barry (2001)

Political Machines

, Athlone Press.

41

J. Urry (2007)

Mobilities

, Polity Press.

42

J. Tomlinson (2007)

The Culture of Speed

, Sage.

43

M. Serres and B. Latour (1995)

Conversations on Science, Culture and Time

, University of Michigan Press.

44

Cf. the work of Parks,

Cultures in Orbit

, and Parks and Starosielski,

Signal Traffic

.

45

Morley and Robins,

Spaces of Identity

.

46

J. Meyrowitz (1985)

No Sense of Place

, Oxford University Press.

47

D. Boden and H. Molotch (1994) The Compulsions of Proximity, in R. Friedland and D. Boden (eds.),

NowHere: Space, Time and Modernity

, University of California Press.

48

Appadurai,

Modernity at Large

.

49

D. Morley (2000)

Home Territories

, Routledge.

50

U. Biemann (2010)

Mission Reports

, Bildmuseet/Arnolfini Gallery.

51

Cf. Appadurai,

Modernity at Large

re “technoscapes.”

52

S. Graham and S. Marvin (1998)

Net Effects

, Comedia/Demos; L. de Cauter (2005)

The Capsular Civilisation

, Reflect Books.

53

H. Bausinger (1990)

Folk Culture in a World of Technology

, Indiana University Press.

54

S. Vertovec (2004) Cheap Calls: The Social Glue of Migrant Transnationalism,

Global Networks

4

; M. Madianiou and D. Miller (2013)

Migration and New Media

, Routledge.

55

Sekula,

Fish Story

; Sekula

Lottery of the Sea

; Burch and Sekula

The Forgotten Space

.

56

M. Levinson (2006)

The Box

, Princeton University Press.

57

K. Manson (2016) Report from Djibouti,

Financial Times Weekend Magazine

(April 2–3), pp. 12–19.