33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

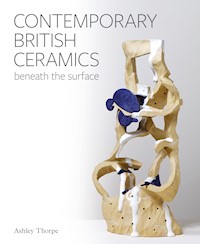

Ceramics is one of the most vibrant and engaging fields of contemporary British art. This lavishly illustrated book reviews the work of twenty-two artists and celebrates their contribution to its rich landscape. Written from a collector's point of view, it explores what contemporary ceramic objects can mean, what emotions they evoke and how artists draw upon different facets of the art and crafts worlds in their work. A vital visual and critical resource, Contemporary British Ceramics showcases British ceramics as a compelling interdisciplinary practice, attuned to the contemporary world. Featuring more than 280 images, it encourages readers to look beneath the surface, to discover the vibrant contribution that British ceramics makes to the broad field of contemporary art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

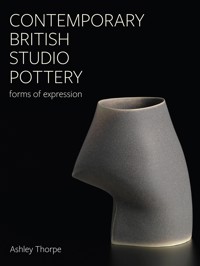

CONTEMPORARYBRITISH CERAMICS

beneath the surface

Merced, California, Pam Su, 2018.

CONTEMPORARYBRITISH CERAMICS

beneath the surface

Ashley Thorpe

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Ashley Thorpe 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 889 4

Cover design: Kelly-Anne Levey

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Contents

Introduction: The Collector’s Eye

1 Richard Slee: Frames of Reference

2 Alison Britton: In Between

3 Jennifer Lee: Drawn Together

4 Carol McNicoll: Montage Notations, Bricolage Citations

5 Sara Radstone: By Accident and Design

6 Pam Su: Directly Indirect

7 Benjamin Pearey: Pages from a Diary

8 Aneta Regel: Ceramic Sculptor

9 Nathan Mullis: Between Worlds

10 Mella Shaw: Prayers for the Future

11 Tessa Eastman: Bridging the Divide

12 Annie Turner: Deep Structures

13 Henry Pim: Structures of Feeling

14 Martin Smith: Un/Divided Lines

15 Aphra O’Connor: Planes, Frames and Spatial Games

16 Patricia Volk: Compositions in Sympathy

17 Ken Eastman: Phenomena

18 Nao Matsunaga: Placed Spaces

19 Sam Lucas: Unexplained MsStories

20 Elena Gileva: Context Dependents

21 Connor Coulston: Portraits of Daily Life

22 Neil Brownsword: Performance Process

Afterword: Beneath the Surface

Artist Biographies

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

The Collector’s Eye

I have called this introduction ‘The Collector’s Eye’ in response to The Maker’s Eye, a Crafts Council exhibition consisting of some 500 objects – textiles, ceramics, paintings, wood, metal and glass – chosen by fourteen craftspeople, held in London in 1982. In the year before the exhibition opened to the public, the Crafts Council published an accompanying catalogue. Selectors were arranged in the volume alphabetically by surname, and essays by two ceramicists with seemingly antithetical views were serendipitously placed next to each other. In the first essay, Alison Britton noted how her selection of works moved beyond utility. She observed how each object gave more than was asked of it, offered reflections on ideology as much as function, and existed in a space somewhere between craft and art. In contrast, in the second essay Michael Cardew asserted functionality as key for the consideration of ceramics as craft, a term he felt needed to be defended from the emergence of a new hierarchy that prioritized ceramics as ‘fine art’.

Grayson Perry, Searching for Authenticity (2018).

(© Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro)

My relationship with ceramic practice rests entirely on the fact that I am a collector rather than a maker. Looking back at The Maker’s Eye catalogue exactly forty years after its publication, I am struck at how much has changed, and how much seems to have stayed the same. In some ways, ceramics as a discipline seems more at ease with itself. The impassioned debates about whether ceramics can or should be ‘art’ have perhaps been settled. Ceramics is an incredibly varied set of practices and ideologies, which includes anything from the most unpretentiously utilitarian bowl through to the most recent developments in fine art sculpture and site-specific performance. The British Ceramics Biennial, launched in 2009, has showcased the array of approaches that exist, and offered a platform of encouragement for recent graduates and established talent alike. Commercial galleries have focused on specific but varied types of work: some showcase more functional ware, others ceramic art and sculpture, and a handful of others exhibit both. Some artists exhibit with craft shops, others with fine art galleries.

Many collectors embrace this range of possibility. Others, I have observed, are much more resistant to it. Pots are an easier sell, and they certainly command the highest prices at auction. Names such as Hans Coper (1920–81), Lucie Rie (1902– 95), Edmund de Waal, Jennifer Lee and Grayson Perry all achieve the eye-watering prices previously reserved for oil paintings and bronze sculpture (in 2018, a Coper vase sold for £318,000). Perhaps people know where they are with a pot; the familiarity of containment, however nominal, is reassuring.

If we look elsewhere, such as in the US, we find a much longer tradition of abstract and sculptural ceramics, and where such work is more readily regarded as contemporary art. In the mid-1950s, whilst Rie and Coper were crafting tea and coffee sets in Albion Mews, Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) was already working with the likes of John Mason (1927– 2019) and Ken Price (1935–2012). These artists were pivotal in redefining what ceramic as a material could do. Utilizing techniques derived from Modernist, Abstract and Expressionist art, they successfully freed clay from its associations with domestic utility.1 The exhibition The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art, held at Yale University Art Gallery in 2015, demonstrated how these artists were deeply integrated with the wider milieu of the American avant-garde. In the US in the 1950s, fine and ceramic art circles were conjoined, and larger works by these artists now command tens of thousands of dollars at auction.

The 2015 Yale exhibition also included work by Rie and Coper. In discussions of line, volume and tone, it can be argued that some of their output contributed to a shift in ceramic practice in the US, and the UK, though in the latter perhaps as much, if not more, through their teaching.2 Certainly, the tone adopted by the curators for these artists was much more benign. It was noted, for instance, how Rie and Coper were resolutely tied to the realm of British pottery.3 Whilst the influence of continental modernism to Lucie Rie, and the sculptures of Henry Moore to Hans Coper, revealed connections to the wider preoccupations of fine art, the exhibition made absolutely no attempt to claim that they were as enmeshed into fine art circles in Britain as their counterparts were in America.4 And that is, quite simply, because they were not. At least, not until the late 1980s and early 1990s, by which point Coper had died. Is this a problem? Yes and no. ‘Pottery’ is not a dirty word. Though I sometimes wonder whether British ceramic artists who do not make pots are overlooked for doing so, whilst also being snubbed by fine art galleries for using (what some art collectors might perceive as) a ‘craft’ material. Things are changing, but progress seems to me to be slow. Why?

There are undoubtedly many nuanced and complex reasons as to why the US and UK should have different aesthetic emphases. We could look, for example, to the different socio-economic and cultural impacts of the Second World War. We could recognize the legacy of mass-produced tableware in cities such as Stoke-on-Trent for framing expectations around ceramic practice as essentially vessel based. We might also look at the pervasive influence of Bernard Leach (1887–1979), and his belief that the Anglo-Oriental approach was the way to unify utility with art. We could explore the impact of Leach’s criticism of artists such as William Newland (1919–88) and James Tower (1919–88) who, by making work influenced by Pablo Picasso in the 1950s, were derogatorily termed ‘the Picassettes’, further cementing a divide between ‘fine art’ and ‘craft art’. We could consider the status of Rie and Coper as immigrants, and the fact that they initially had to situate their modernism within the prevailing Leach aesthetic. There is also the role of government institutions in promoting certain ideologies around craft, and the significance of museum acquisition policies privileging certain practices over others. All of this, and undoubtedly a great deal more, has played a part.

In recent decades, there have been significant attempts to communicate to a wider public how contemporary ceramic artists work across forms, practices and approaches. The ceramic galleries of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, for instance, have sought to challenge perceptions with a host of temporary exhibitions and artistic residencies, many of which exhibitions of ceramic sculpture by Gillian Lowndes (1936–2010) and, by holding examples of work purchased by the collector Anthony Shaw on long-term loan, brought sculptural work by the likes of Ewen Henderson (1934–2000), Sara Radstone and Eileen Nisbet (1929–90) to new audiences.

If anything surprises me about the forty years since The Maker’s Eye, it is that the mingling of ‘art’ and ‘craft’ has not become a more commonplace approach in exhibition curation.

Yet, the problem with any public gallery is that it has to classify its collections according to material. Ceramics in a dedicated gallery is a double-edged sword: it necessarily highlights ceramics as a practice and enables stylistic changes within the discipline to be observed. However, it is also more difficult to perceive its connections with other artistic movements, and perhaps risks clay being determined as a rather self-referential medium. Disappointingly, the exhibition A Secret History of Clay: from Gauguin to Gormley, held at Tate Liverpool in 2004, emphasized fine artists who engaged with ceramic practices (the approach of fine artists perhaps demonstrates less understanding of the history of ceramics than those who studied it at art college). It included only a handful of ceramic artists moving into fine art (two with pots, one with tiles), and rather overlooked the vital interconnections between painting, sculpture and ceramics.

If there is a ‘secret’ history of clay, it is that studio ceramics has been a fertile area of enquiry precisely because it has always brought together different arts practices. Yet, this is nothing new. Japanese Jōmon (14000–300 BCE) and Chinese Majiayao (3300–2000 BCE) cultures made both ceramic pots and sculptures are not rooted to the vessel. A number of the artists featured in this book have participated in this scheme. Similarly, the Centre of Ceramic Art in York has mounted using carving, sculpting, hand-building, drawing and painting skills. Contemporary British ceramic practice as described in this book is doing nothing more than flexing the ancient muscles of the medium.

If anything surprises me about the forty years since The Maker’s Eye, it is that the mingling of ‘art’ and ‘craft’ has not become a more commonplace approach in exhibition curation. It is particularly surprising because a number of contemporary makers continue to draw, paint and make prints. But it also helps to illuminate what is going on in terms of dialogue. As an ideological platform, The Maker’s Eye empowered Alison Britton to convincingly describe a significant mutation in British ceramic practice. Britton herself has been inspired by the US artist Betty Woodman (1930–2018), whose work sits in between ceramics, sculpture and painting.5

Bryan Illsley, Hoarse, featured in Fun and Games, his 2014 solo show at Marsden Woo Gallery.

(© Philip Sayer. Courtesy of Marsden Woo)

This amalgamation of disciplines has also been important for Britton’s own practice, as demonstrated in the essay on her work included here. To my mind, Britton, and others (Richard Slee in particular) have engaged with the opening out of perspectives offered by ceramic abstraction from the US as much as, if not more than, the modernist and sculptural impulses of Coper and Rie.6 Perhaps by offering an alternative to Michael Cardew’s validation of the Leach doctrine, Britton’s essay in The Maker’s Eye gave words to a conceptual space that a number of British artists already inhabited, but which had not otherwise been formally articulated. Her essay continues to be relevant because it argues for the unification of intellect, artistry, skill and playfulness beyond the constraints of utility. As I look across this volume, I find such unification in abundance.

Nevertheless, sculptural ceramics is not new to Britain. The brilliant The Art of the Modern Potter by Tony Birks, first published in 1967, documented works by Ruth Duckworth, Ian Godfrey, Bryan Newman and Anthony Hepburn. All of these artists, especially the latter, sought out new sculptural vocabularies for clay that seem contemporary even now. Over the past few decades, the likes of Jill Crowley, Kerry Jameson, Claire Curneen and Bryan Illsley have created a compelling body of abstract and figurative sculptures. My riposte to any naysayers who are dismissive of work beyond the vessel is that ceramic art does not have to look like a pot to be a container. Ceramic sculptures might not be designed to hold water, but they certainly hold ideas. They carry liquid meanings: our desires, fantasies, dissatisfactions, memories and passions.

I am very aware that, with the exception of some works by Martin Smith, there are no throwers included in this book. It is not that I dislike thrown pots, feel they are lesser, or consider them devoid of interest. As a collector, I love all forms of ceramics, and it is the malleability of the material that stimulates me most. It is more that I have had to implement criteria to make the volume feasible. Paul Rice’s British Studio Ceramics (2002) focuses exclusively on the vessel, much of it thrown, and so I have sought to offer something of an alternative here. I have also chosen to concentrate on artists who are still active, meaning the work of luminaries such as Nicholas Homoky, Rupert Spira, and the late Janice Tchalenko (1942–2018) and Robin Welch (1936–2019) are regretfully omitted. Other important names – Gordon Baldwin, Claire Curneen, Edmund de Waal, Walter Keeler, Magdalene Odundo, Grayson Perry and Julian Stair – have been written about elsewhere.7 In any case, this book was never meant to be a comprehensive survey. Rather, I have sought to offer a deeper reflection on the work of specific artists, and interweave established names with emerging makers, some of whom have never been written about before.

In this respect, I am most influenced by the structure of The Art of the Modern Potter. Any volume reflects the tastes of its author, and in what might seem like a blindingly obvious statement (but one that is often glossed over), I have only written about work that I like and when I feel I have something to say. For artists nearer the start of their careers, and who are still in the process of discovering their voice, I have responded to what I perceive as exciting discoveries in their work, even if these prove to be transient. For more established artists, I have tried to find a new angle on their practice.

Although Britain is the focus for this volume, this particular constraint should not be regarded as an endorsement of nationalist insularity. If anything, British ceramics seems more international than ever. British artists regularly exhibit abroad, both in solo and group shows. In fact, some artists find it easier to exhibit abroad than they do in Britain, a sad and rather telling indictment. Social media has enabled artists from around the world to share their work and comment upon it, and British artists can participate in international discussions about practice without even leaving their studio. The artists explored here demonstrate an interest in, and a response to, work from Europe, the US, Japan, and elsewhere. This influence is not just confined to the field of ceramics, but also extends to wider fine art and sculptural practice, as well as the critical writing that accompanies it.

From the outset, I wanted this book to be critically engaged, accessible, and a good thumb-through. I also knew I did not want a lot of section headings. Some books bracket artists together through shared themes or approaches, such as ‘materiality’, ‘space’, the ‘abstract’ etc. I understand the value of this approach, but equally I am often left confused as to why one aspect of an artist’s work, such as ‘material’, has been deemed more important than another, say ‘space’. Why must artists only appear in one category in a book when their work is out of necessity much broader? There is a risk, I think, of distorting what the work actually is in order to meet the demands of a particular thesis.

Neither did I want this volume to follow the educational approach. This proposes that if artists trained at the same institution, perhaps under the same teacher, it follows that their work must be broadly similar. Not everyone who studied ceramics at Camberwell, the Royal College of Art, or wherever else, produces work according to the same aesthetic ideals. This is not to say that artistic genealogy does not have its place. There can, however, be an over-emphasis on education as the primary determinant. In saying all this, I am not anti-theory, or anti-history. It is simply that, in this volume, I have sought to approach contemporary ceramics in Britain in a slightly different way.

The guiding principle in this volume has been remarkably simple: treat each work as its own object in the world. By framing the analysis in this way, I have tried to think about what these pieces evoke as works in their own right. How might they make us feel? How does ceramic relate to other arts? How might one aspect of an artist’s work resonate with another? These essays stand as records of my perception of the work and its meaning as expressed in the examples I have selected. It is entirely subjective. My approach to each chapter has also been quite uniform. I have formulated my ideas, usually in relation to an existing concept, and then approached each artist to seek permission to write on them. I have then tested out my thinking, either by meeting the artist and discussing their work in person, or by sending them the writing for a response, or, more often, both.

Claire Curneen, Tending the Fires (2016).

(Photograph by Dewi Tannatt Lloyd)

You will, of course, be approaching this book with different motives and priorities. For some, flicking through the pages to look at the images will be the main concern. This is how it should be. Certainly it always is for me: why else would you buy an art book? In structuring the accompanying text, I have tried to account for different approaches to its reading. Each chapter is self-contained, enabling you to dip in and out the book as you see fit. For those who decide to read the book chronologically, I have placed artists in close proximity where there is a shared vocabulary or point of reference. This is not so much putting work into conceptual boxes; more curating it into echoes and synergies, as well as very real and significant differences. For this reason, I do not consider the lack of sub-sections in this book to be a critical retreat. Quite the opposite, in fact.

There is a definite logic suspended in the progression of the essays. Moving from the first to last chapter, there emerge questions concerning the relationship of ceramics to painting, drawing, memory and emotion, ecological disaster and the environment, place, architecture and space, identity, and history. These categories are not exclusive: the essays speak to many of these concepts in different ways. The critical perspective I offer here is to state categorically that thematic relationships are more complicated and nuanced than sub-sections can ever hope to convey. Should you journey through the book from beginning to end, the themes will mutate as you progress, and you will find the strongest conceptual synergies between essays in proximity. However, the first and last essays should not be regarded as end points in a spectrum. Rather, these chapters – focusing upon the work of Richard Slee and Neil Brownsword – explore how work sits amongst and between the categories of ‘fine art’ and ‘craft’. In this sense, the volume has a very circular structure; you can read chronologically from any chapter and end up back in the same place.

I have to admit that when I look back on the process of writing this book, I cannot help but wonder what each artist made of me when I marched up to them and brazenly responded to their work. But I have been consistently amazed at the generosity of their response. I remain indebted to all of the artists included here for their time, tolerance and support in responding to the writing, and in liaising with their equally generous photographers to enable pictures of their work to be reproduced. Each essay has been read by the artist prior to inclusion. Some made suggestions, others did not, but in all cases the writing remains my own response to their work. There is a short biography for each artist at the back of the volume, but there is otherwise no statement by them on their practice. This, I think, is important to viewing their work in the world: that is, as works that are discovered without a need to validate responses through biography, the artist’s own thoughts, or technical processes.

Claire Curneen, Detail of Tending the Fires (2016).

(Photograph by Dewi Tannatt Lloyd)

Grayson Perry, Sales Pitch (1987).

(© Grayson Perry. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro)

As someone who is not a maker, I only have a rudimentary understanding of clays, glazes, and firing temperatures. I have not asked artists to supply this information in detail, and I accept that this might be frustrating for some readers (and perhaps some artists too). For me, there is an element of mystery in how these pieces are produced, and I feel this has equivalence in discussions of other arts. Fine art criticism, for instance, does not tend to focus on technical details at the expense of other kinds of analysis, even if it includes reference to conventions (e.g. the golden ratio in painting). Certainly, painters are rarely asked to document the five pigments they mixed together to get the shade of green they used for blades of grass in an oil painting. It is not the point. In accepting that ceramics is its own medium, has its own needs, languages and perspectives, I still do not feel compelled to include technical data. There are plenty of books about this already. The focus here is on the work produced and its impact; how it got into the world is of less importance to me than the fact it is here at all.

These essays, then, represent my honest responses to the work, written from the heart as much as the head. For me, ceramics have become tied to everyday experience in distinctive ways. What might seem like mundane or trivial incidents can sometimes trigger a particular way of responding to an artist’s work. If parts of this volume seem autobiographical, this arises simply from the fact that the works I have selected are sewn into the fabric of daily life. I am sure that an artist, dealer, curator, historian or critic would have a very different take on the questions I have explored in this introduction, and which reverberate across the book. But I am not pretending to be something I am not. I am a collector, and I speak from that position, with respect, affection and conviction. What follows is nothing more than a view from the collector’s eye.

Richard Slee

Frames of Reference

Art [...] differs from handicraft; the first is called free, the other may be called mercenary. We regard the first as if it could only prove purposive as play, i.e. as occupation that is pleasant in itself. But the second is regarded as if it could only be compulsorily imposed upon one as work, i.e. as occupation which is unpleasant (a trouble) in itself, and which is only attractive on account of its effect (e.g. the wage).8

This rather snobby division between art and craft – of art exhibiting a playfulness and love of beauty for its own sake, whilst craft simply being a highly skilled imposition that earns a crust – was proposed by the influential German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). In The Critique of Judgement published in 1790, Kant sought to understand how it was possible for us to recognize and experience beauty. Kant’s analysis has been developed, and critiqued, but has remained a highly influential theory. Indeed, I regard it as a useful frame of reference for exploring the work of Richard Slee. In 2018, Slee held an exhibition, Framed, at the Crafts Study Centre in Farnham, Surrey. The exhibition consisted of twenty-five wall-mounted works, many of the pieces taking the form of found objects edged by ceramic frames. The exhibition raised questions about the divide between art and craft, the nature of the boundaries, and the possibility of their blurring.

In order to understand the implications of the divide between art and craft, and the challenge Slee’s work offers to it, we first need to explore Kant’s ideas in more detail. Kant offered four observations, a kind of criteria, about how we experience beauty and, in turn, how we come to recognize fine art. His first assumption was that:

Taste is the faculty of judging of an object or a method of representing it by an entirely disinterested satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The object of such satisfaction is called beautiful.9

For Kant, there was an important distinction between things that we produce because we need them to survive, and things we make simply because they give us pleasure. For an object to be beautiful, it cannot be functional. Indeed, Kant argued that producing an object was not a remarkable thing in itself; all livings things produce what they need to survive. Bees make honey, spiders make webs to catch flies; only humans produce things that they do not actually need. For Kant, this was the first requirement for an object to be beautiful, and by extension, to be art; it must have no industrial benefit, no utility, no need beyond its own existence. Thus, when we look at art, we are not looking at it in an interested way (that is, in terms of how we can use it to help us survive), but what Kant describes above as a ‘disinterested’ way. We contemplate the object simply for its own sake. If we look at an object in this disinterested way, and find it to our ‘satisfaction’, we find it beautiful. If it gives us ‘dissatisfaction’, we do not.

The beautiful is that which pleases universally, without a concept.10

Secondly, if everyone can feel pain, Kant observed, then everyone can feel pleasure, and so beauty must exist as a universal phenomenon. For something to be beautiful it must be liked by more than one person. Whilst taste varies between individuals, an object will not be validated as beautiful if only one person thinks it is; beauty is a socialized phenomenon.11 Furthermore, Kant suggested that in the aesthetic contemplation of an object, we look ‘without a concept’. What he means is that when we look at something in a disinterested way, our imaginations go into overdrive, and we open up a number of different conceptual understandings about what we see: there is not one correct interpretation. Kant called this appreciation of an object without a concept ‘Free Play’. Free Play is a crucial mode of analysis that our minds enter into when we make aesthetic judgements about beauty.

Beauty is the form of the purposiveness of an object, so far as this is perceived in it without any representation of the purpose.12

Thirdly, Kant argued that for something to have beauty, it has to set out to be beautiful in the first place, but it cannot look like this is what it is setting out to do. This might seem self-evident, but he argued, for instance, that a flower is beautiful to us simply because it was grown and made (its ‘purposiveness’) to be beautiful. Bees could not find a flower beautiful, assuming they could have such a judgement, because their interest was in a practical search for nectar. Similarly, in art, a painting can be beautiful because it is designed and made to be beautiful: this is its sole purpose. Yet, when we contemplate art, we do not want to feel that we are being manipulated into appreciating beauty. If we become too aware of the artist’s labour, we look at a painting in terms of how it elicits our feelings, that is, we focus on the labour of the artist’s technique. In such instances, our own ‘disinterested’ aesthetic experience is lost; rather, we become ‘interested’ in how the artist achieved the work, and view the painting as a kind of skill or craft, and not as art.

The beautiful is that which without any concept is cognised as the object of a necessary satisfaction.13

Finally, Kant argued that beauty rests upon supplying us with some kind of aesthetic satisfaction. Again, this seems self-evident, but it is nevertheless an important point. If an object does not satisfy us (give us ‘necessary satisfaction’), we will not find it beautiful.

The significance of Kant’s ideas to the analysis here rests upon recognizing that we apply certain kinds of criteria to help us distinguish art from other kinds of object. We make art ‘special’. How? When we want to experience and appreciate art, we go to special buildings (galleries), into special rooms (exhibit ions), to look at paintings on a white wall free of other visual distractions, and which are made even more important by being marked out by a picture frame. All of this facilitates, as observed by Kant, a disinterested way of looking at an object. We dismiss the practical and look for the aesthetic. By going to a gallery, we actually make a physical effort to separate ourselves from the daily lives of work and family, to stop thinking about what we need to do to survive, and to instead immerse ourselves in a search for beauty. Indeed, art, for most of us at least, is not a daily experience; it is a special activity. The hushed environment of a gallery, should we happen upon it, assists us in our search for aesthetic enlightenment by reinforcing our temporary removal from the humdrum of the daily grind.

If we follow Kant’s ideas, ceramics, as a craft practice, is concerned with function, and so it cannot be art. A pot is designed to be a useful container: it cannot be pure beauty. The judgement we make about a pot fundamentally rests upon whether it can do the job of holding a liquid properly. We do not need to go to a special gallery to experience ceramics. In fact, they are such a fundamental part of our daily lives that we need go no further than the kitchen. All of this rests, of course, on the assumption that a theory from 1790 still holds water. It seems to me that many contemporary ceramic artists have overturned some of these assumptions. Richard Slee is certainly one of them.

How does a pot become art? Context demands from the spectator a very particular way of seeing. Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) understood this only too well when he famously took a readymade ceramic toilet urinal (‘not art’), and, stripping it of its possible function, put it in an art gallery in 1917 (now ‘art’). Equally, Grayson Perry has shown that the unassuming shape of a pot – bound up with the daily, the disposable and the domestic – is the perfect vehicle for smuggling unsettling imagery into the fashionable galleries of the contemporary art world.14 Once a pot is in a gallery, people are forced to look at it differently, as art, and not wonder about whether it will leak if filled with liquid. Such shifts in context are crucially important when considering the artworks (note the term) of Richard Slee. Framed brought together a number of different worlds – craft techniques, the handmade, the readymade – and, in what stands as a strong riposte to Kant, quite literally reframed these things into fine art.

Space (2015).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

There remains something mischievous about putting an art exhibition on in a craft centre. Slee designed the exhibition specifically for the Craft Study Centre, and so the politics of this decision is very resonant. The Crafts Study Centre originated at the Holburne Museum in Bath, where it opened in 1977, before moving to Farnham in 2000. It includes an extensive archive about, and numerous world-class examples of, studio ceramics, calligraphy, wood, furniture and textiles. It holds some works on paper, but it is by no means an Art Gallery. In Framed, Slee showed that the divisions between art and craft are very tenuous, if not ultimately irrelevant. At least half of the overall material on display was ceramic, but since the works were all designed to be fixed to the wall, there were no plinths or shelves. The exhibition space was designed to perform like an art exhibition. Slee seemed to be provoking his audience: if you come to a craft gallery to see a ceramics show, and are confronted by a fine art experience, you will be tested against your own preconceptions. Look for craft and you will see craft. Look for art and you will see art. Look for both and you will find the work of Richard Slee.

The pieces in Framed were made entirely from found objects, processed by Slee in particular ways. During one of his adventures around pound shops, Slee came across a range of baroque-style plastic picture frames. There is an interesting conceptual tension in these objects that no doubt aroused Slee’s interest. In these frames, the baroque style – the ornate grandeur of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries – has been mass-produced in plastic and sold, at profit, for only one pound. They capture a wider sense of collapse between high art and mass consumerist culture. More people have seen Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503) as a digital image, a poster or a postcard, than in the flesh as an oil painting. Of those who have made the pilgrimage to The Louvre, many will simply have been jostled past it by the crowds. So much for the quiet contemplation of beauty. Kant, one imagines, would disapprove. Slee’s engagement with these picture frames relates to wider questions of cultural value, the impact of mass production, and the increasingly topsy-turvy relations we have with the concept of high art.

Slee created plaster moulds from the plastic frames and used press-moulding techniques to create his ceramic copies. The frames were populated with other treasures from pound shops: lenticular prints, fablon, and sections of plastic and metal. If the baroque plastic frames brought high art into the consumer market, Slee’s decision to frame these bargain objects in the exhibition elevated them from the cheapest art commodities into the subject matter of high art. Slee’s trademark style – the bright colours and glossy sheen – make the frames appear cartoon-like, implying his awareness of the transactional changes in value he has initiated. As art works by Slee, these frames are now worth far more than they cost to source and make. Yet, such upcycling is in keeping with the broader concerns of Slee’s practice. From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, he produced a number of sculptural works that featured miniature ceramic figures; some sourced from a collection his daughter had discarded, others bought from charity shops (see, for example, Landscape with Hippo, 1997, now in the ceramic collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum). Slee’s work has long brought the ‘mass-produced’ into the domain of ‘the unique sculpture as artwork’. In so doing, he has blurred the divisions between art, craft, and the mass-produced.

Deeper Space (2015).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

It is clear that Framed sits in between the art/craft divide when focusing on specific pieces. The subject matter of each work can be categorized in numerous overlapping ways. Some of them focus on astronomical space to consider questions of pictorial space. Space (2015) is an entirely ceramic work created in the same colour. Here, a sense of space is contingent on a lip creating a visual separation between the image and the frame that surrounds it. Yet, these two elements are mutually dependent: without the frame the picture is not delineated and thus it does not exist. In Space, the frame, usually considered supplementary to the image, actually creates the main image. Thus the frame is given visual equivalence to the picture by creating both in the same material and colour. The perception of depth arising from the frame lip is extended in Deeper Space (2015), where the same colours are deployed as in Space, but a lenticular image deepens the spatial perspective. The three-dimensional image is at odds with the flattening effect of the frame, and in turn, the frame’s relationship with the wall.

Wasteland (2018).

(Photograph by Damian Griffiths, courtesy of Hales Gallery)

Green Field (2015).

(Photograph by Damian Griffiths, courtesy of Hales Gallery)

Other works referenced fine art landscape painting. Frame and subject were again fused in Wasteland (2018), where a dead tree was modelled into the structure of the frame itself. A tile, chosen because it has a kind of horizon line, was placed behind the tree to form the pictorial space. The frame activates the tile – a found object – into a landscape. This complex and clever work demonstrates Slee’s understanding of the power of framing, in both a literal and conceptual sense, to our perception of objects. Recontextualizing an everyday object profoundly alters our experience of it. In the same way, Green Field (2015) frames green plastic grass to offer a witty evocation of a field.

Reference to fine art also included specific movements and styles. In Impression (2018), Slee used glaze across a flattened plane to evoke the impressionist strokes of Monet’s paintings. No Title (2018) could easily have been a print by Victor Vasarely or an early work by Bridget Riley, but it is in fact a found piece of printed plastic (plastic also being a medium used by op-artists). Abstract (2018) is self-evidently abstract art, whereas the diptych Something to Think About (2018) offers a humorous take on conceptual art, where the title simultaneously directs and obscures the meaning of the work.

Impression (2018).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

No Title (2018).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

Abstract (2018).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

Something to Think About (2018).

(Photograph by Damian Griffiths, courtesy of Hales Gallery)

Purple Grill (2018).

(Photograph by Richard Slee)

This is not to suggest that Framed is not conceptual art. As a body of work, it absolutely is conceptualized, and skilfully so. Slee works, not in series, but in relation to constraints that require specific kinds of answers.15 Here, picture frames offered a literal and theoretical constraint within which to work. They enabled him to consider how readymades are recontextualized into art through the device of framing at a literal, institutional and conceptual level. Yet, they also document a more straightforward joy in colour, shape, texture and rhythm discerned in the objects of the everyday. There is obvious delight in finding an object in a bargain shop, releasing it from its historical meaning and daily use, and placing it into a new context where it only refers to itself. Something to Think About and Purple Grill (2018) aptly demonstrate this. Indeed, the plastic in these works has greater resonance with Abstract Expressionist artists like Roy Lichtenstein than the everyday object. Yet, there is no attempt to disguise the fact that these are found objects. In fact, the works are contingent upon the spectator recognizing their duality as found objects altered into the status of fine art. Each work thus has a triple subject: the frame, the framed, and the relationships between the two. We are able to see how Slee is using the frame to shift, even reframe, our perception of each object as art, but also how there is potential for art all around us in our daily lives if we choose to look for it. The key to unlocking this lies in imagination and play.

Kant proposed that art has to be regarded 'as if it could only prove purposive as play, i.e. as occupation that is pleasant in itself.' Craft, however, 'is unpleasant (a trouble) in itself, and which is only attractive on account of its effect (e.g. the wage).'16 Slee’s ceramics are a product of play, of labour, and of craft skill. Indeed, if the pursuit of aesthetic beauty is predicated on looking at something in a 'disinterested' (that is, non-utilitarian) way, then Slee’s reframing, repurposing and even dis-functioning of found objects means they have to be regarded as art. In fact, Kant’s notion of Free Play is clearly at the heart of everything Slee does.

Framed asks us to look at how we see things, how we frame things, and challenges us to reconsider what we view as important. This is proven by the fact that in Framed