Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Ceramics

- Sprache: Englisch

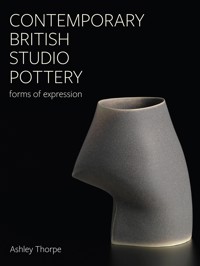

Pots have existed across the world and in different cultures for thousands of years. This volume explores how contemporary makers use the ancient language of the pot to convey contemporary ideas, from the sculptural and painterly to the ecological and satirical. This beautifully produced book is a visually rich and critically in-depth focus on the work of twenty-four potters. A companion volume to Contemporary British Ceramics: Beneath the Surface, it reveals how pots can be extraordinarily powerful forms of expression.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction: What is a pot and what is not?

Formal Languages

1. Magdalene Odundo: Glossolalia

2. Tina Vlassopulos: Space for Imagining

3. Julian King-Salter: Twists and Turns

Dialogues with Twentieth Century Art

4. Dan Kelly: In Contrast

5. Elizabeth Fritsch: A Responsive Eye

6. Sam Hall: The Muse of Fire

7. Sara Flynn: Drawn to Life

8. Julian Stair: On the Table

Dialogues with the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

9. Jo Taylor: Re-collections

10. Matthew Warner: Status Symbols

11. Paul Scott: Breaking with Tradition

12. Stephen Dixon: Satura

13. Frances Priest: Neo-modernisme

14. Nico Conti: Ceramic Surgeon

The Tangible

15. Toni De Jesus: Points of Contact

16. Gareth Mason: Tripartites

17. Sarah Purvey: Streams of Consciousness

The Intangible

18. Chun Liao: Palimpsests

19. Nicholas Rena: Matter That Matters

20. Lawson Oyekan: A Unified Theorem

21. Akiko Hirai: Nothing Comes from Nothing

Colliding Worlds

22. Tim Copsey: Tableau-ware

23. Gabriele Koch: Metaphorica

24. Márek Líška: Here and Now

Afterword: Forms of Expression

Artist Biographies

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Image Credits

Index

Introduction: What is a pot and what is it not?

The ‘vessel’, it seems, is a contentious word in ceramics. As Laura Gray has noted, debates surrounding the validity of the term reveal ‘tensions about the relative value of the pot, the vessel and the object, and the status between the useful and the useless in the art world.’1 As Gray goes on to observe, the word ‘vessel’ brings to the fore anxieties about craft, its relationship to fine art, the relevance of utility, even accusations that ceramicists are guilty of self-aggrandisement.2 The debate as to whether ceramics should be regarded as ‘art’ or ‘craft’ (even subject to the same kinds of criticism as fine arts) was particularly vehement in Britain in the 1980s.3 Rather than being resolved, however, the debate simply fell to the wayside. When Grayson Perry won the Turner Prize in 2003, pottery was widely considered to have entered the world of British fine art, as if a trophy was all that was needed to iron out the polemics of the preceding decades.4 Yet, as Perry admits of his own training, ‘the main reason for not taking up throwing was that I wanted to avoid the signature ceramicist’s skill because it would mark me too easily as a potter and I was clinging onto my newly minted identity as a contemporary artist’.5 As Perry went on to observe, ‘pottery was craft, not art, pottery was the business of skilled tradesman not gentleman academics, pottery was humble, small and domestic and seen as feminine.’6 Indeed, Perry’s work has readily exposed, rather than erased, the divisiveness of ceramic art/craft discourse.

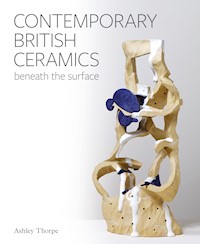

Many of the artists included in my first book, Contemporary British Ceramics: Beneath the Surface (2021), made sculptures. This was a deliberate choice. I was interested in capturing the interdisciplinary nature of contemporary practice, and I wanted to focus on – what seemed to me at least – some of the less readily accepted branches of contemporary British ceramics. This necessitated moving across different formal concerns. However, makers of pots and vessels were still included; artists such as Alison Britton, Ken Eastman, Jennifer Lee, Carol McNicoll, Sara Radstone, and Martin Smith, were an integral part of the discussion because their work related to many movements, themes, and ideas. These included drawing, painting, film, modernism, postmodernism, architecture, history, identity, and belonging. From this interdisciplinarity, I was soon convinced that the impassioned arguments as to whether ceramics was or is fine art or craft were retrograde. Indeed, over the last forty years or so, and with the benefit of hindsight, I am left to conclude that the claiming of ceramics as either art or craft was not just futile, but a disavowal of the kinds of work produced.

Art or Craft?

In his excellent analysis of the history of the word ‘craft’, Paul Greenhalgh demonstrated how the meaning of the term shifted from the seventeenth century, partly in response to developing class politics. Indeed, the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that:

Art […] differs from handicraft; the first is called free, the other may be called mercenary. We regard the first as if it could only prove purposive as play, i.e. as occupation that is pleasant in itself. But the second is regarded as if it could only be compulsorily imposed upon one as work, i.e. as occupation which is unpleasant (a trouble) in itself, and which is only attractive on account of its effect (e.g. the wage).7

For Kant, craft was produced for money, whereas art existed for its own aesthetic sake. Presumably art was not produced for financial reasons because it was either practised, or patronised, by the upper classes. Such collectors were perhaps less interested by the cost of the works they acquired, more the social and cultural capital of owning a collection. Craftspeople, presumably typified as lower class, needed to make a living from their wares because they had to put food on the table.

By the time of the late nineteenth century and the arrival of the Arts and Crafts Movement, craft was used to refer to any decorative art (an eighteenth-century catch-all term for all artistic practices excluded from ‘fine art’) that was non-industrial and community-produced, with the concomitant belief that such creative labour was for the common good.8 Indeed, William Morris (1834–1896) defended craft in his 1882 lecture The Lesser Arts of Life, arguing that ‘if our houses, our clothes, our household furniture and utensils are not works of art, they are either wretched make shifts or, what is worse, degrading shams of better things.’9

In the aftermath of the success of the Arts and Crafts Movement, craft became a more widely understood term. Craft became tied to anti-industrial discourses, and it was in this context that Bernard Leach (1887–1979) rose to prominence.10 Leach became the dominating ideological force of the British studio pottery movement for much of the twentieth century. In A Potter’s Book (1940), Leach suggested that ‘a pot in order to be good should be a genuine expression of life. It implies sincerity on the part of the potter and truth in the conception and execution of the work.’11 Such a view echoed William Morris; that the best pots should be consequential, engaging us through sight and touching us through tactility. Yet, for Leach, such aesthetic experiences were tied to his universalist beliefs that art should inspire a cosmopolitan shared world culture of humanity. It is for this reason that Leach was such an ideological advocate for connections between ‘East’ and ‘West’. After all, the bridging of cultures brought all of humanity together in the appreciation of a common aesthetic. Such ideas seem rather generous in spirit, and do not, in and of themselves, deem functional pots to be the worthiest. Nevertheless, his beliefs in artistic sincerity were inextricably tied to utility, where ‘the form of the pot is of the first importance, and the first thing we must look for is […] proper adaptation to use and suitability to material.’12

Bernard Leach, ‘Leaping Salmon’ Vase (c.1960).

Such doctrinal thinking glossed over contemporaries who sought to align pottery with modernist fine art. In inter-war Britain, the work of William Staite Murray (1881–1962) had successfully situated pottery as a parallel activity to sculpture and painting. Regarded as antithetical to Leach’s utilitarian artisanry, Staite Murray’s solo exhibitions of pottery earned him critical acclaim, and by the 1930s he was exhibiting with the Seven and Five group of modernists (which included Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore). Yet, as the 1930s wore on, influential art critics turned against Staite Murray’s work for its apparent self-indulgence.13 Following the dissolution of the Seven and Five group in 1935, Staite Murray emigrated to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1939 and ceased potting.14 In the decades that followed, Staite Murray’s success in arguing for pottery as a mode of fine art expression was downplayed by Leach and his supporters.15 Thus, the philosophical thrust of most British studio pottery became tied to utility.

Leach’s philosophy was so prominent that it persisted in some quarters until the turn of the century. As late as 1998, the ceramicist and critic Peter Lane was still suggesting that:

The form of a vessel often suggests that it can perform some kind of useful purpose in addition to the decorative aspects of its being. When vessels are primarily intended to serve as containers, that special function must be carefully considered and incorporated into the initial design.16

Lane was aware of artists who made pots that were not intended for use, for the volume was illustrated with numerous examples. Furthermore, all pots have ‘useful purpose in addition to the decorative aspects of its being’, making his distinction between a pot and a vessel obscure. In his concluding chapter, ‘Traditions and Innovations’, Lane nevertheless noted how, for some contemporary artists, ‘utilitarian aspects in even the most familiar shapes of ceramic vessels are of little or no interest.’17 Yet, by pushing the discussion of these artists to the final (somewhat shorter) chapter, they were still positioned as a departure from the mainstream. Perhaps in the 1970s and 1980s this might have been assumed by the casual observer, but by the turn of the century, the landscape was far more diverse.

The Turn to Painting

In the USA, things had proceeded very differently. In 1961, the important critic Rose Slivka articulated the impact of Abstract Expressionist painting on ceramic practice. Her observations were providential, and are worth quoting at length:

Painting shares with ceramics the joys and the need for spontaneity in which the will to create and the idea culminate and find simultaneous expression in the physical process of the act. Working with a sense of immediacy is natural and necessary to the process of working with clay. It is plastic only when it is wet and it must be worked quickly or it dries, hardens, and changes into a rigid material.

The painter, moreover, having expanded the vistas of his [sic] material, physically treats paint as if it were clay – a soft, wet, viscous substance responsive to the direction and force of the hand and to the touch, directly or with tool; it can be dripped, poured, brushed, squeezed, thrown, pinched, scratched, scraped, modeled; treated as both fluid and solid. Like the potter, he even incorporates foreign materials – such as sand, glass, coffee grounds, crushed stone, etc. – with paint as the binder, to emphasize texture and surface quality beyond color.18

The overlaps – and significant differences – that Slivka identified between painting and ceramics encouraged an understanding of how technique, form, approach, and treatment, could establish new modes of expression in clay. It is not that painting and ceramics were the same; more that they had overlaps that were fertile areas of investigation. By the 1960s, US artists such as Peter Voulkos (1924–2002) and then Ron Nagle (b.1939) had become leading names, capably demonstrating the expressive possibilities of new ceramic forms.

Such ideas arrived in Britain somewhat later and became hybridised with (and used as a response against) the prevailing Leach ideology. The pot would not be discarded, but it was considered that utility need not be the primary formal concern. In her important essay for The Maker’s Eye exhibition held in London in 1982, Alison Britton observed how, in her curated selection of objects (which included ceramics, textiles, jewellery, glass, wood, and metalwork) she sought:

to make a comparison evident between ‘prose’ objects and ‘poetic’ objects; those that are mainly active and those that are mainly contemplative. To me the most moving things are the ones where I experience in looking at them a frisson from both these aspects at once, from both prose and poetry, purpose and commentary. These have what I call a ‘double presence’.19

In comparison to Slivka’s observations, Britton’s were somewhat more conservative, though it must be noted that Britton was reflecting upon her own curatorial choices, rather than agitating for the wider field. However, in time, the essay would do just that, being cited in arguments for new approaches to the pot in Britain as a conceptual and formal device. In her essay, she noted, for instance, how her emphasis on ‘vessels’ ‘could be somehow inherent in the training of a potter’, or a product of ‘clinging to the residue of use as a justification’, or even a recognition of ‘vessels’ as ‘basic, archetypal, timeless.’20 Nevertheless, whilst the pot was central to tradition, it did not mean it had to be ‘traditional’. As an example, Britton explored the work of Andrew Lord in relation to painting, noting how his three-dimensional works ‘retain some of the imprecision and loose, impressionistic quality of a two-dimensional representation.’21

Despite her intentions, Margetts’s observation that modernism had been rejected in some ceramic practices from the 1970s and 1980s glossed over, rather than resolved, the awkward art/craft debate she sought to rationalise. Whilst Margetts highlighted how the modernist ethos of Bernard Leach had been questioned, no one seemed to observe that a logical extension of her argument at this time would be to similarly reject Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, whose modernisms had been construed as antithetical to Leach.24 In general terms, Rie, Coper, and Leach were not all that oppositional in seeking a transcendent aesthetic for their work. Indeed, Leach famously gifted Rie a large white Korean Joseon Dynasty Moon Jar (now in the collections of the British Museum).25 Perhaps this was tacit recognition that Rie’s work, like his own, could combine ‘East’ and ‘West’ aesthetics in the search for universalist values, even if their approach to form was very different. Indeed, outside Europe, the strongest audience today for Rie and Coper is, in fact, in Japan. Thus, the apparent rejection of modernism in the 1980s and 1990s was somewhat contradictory, with Leach facing critique, but Rie and Coper receiving credit for fostering a whole generation of new makers.26 In reality, as documented in Chapter 1 exploring the work of Magdalene Odundo, the rejection of modernism was selective and uneven.

A decade later, the exhibition The Raw and the Cooked: New Work in Clay in Britain, toured Britain between 1993 and 1995. Funded by the Crafts Council, the exhibition was curated by Britton and Margetts. With a more expansive range of approaches, Margetts was able to confidently make her point:

Lucie Rie, Tall Vase with Flared Lip (1979).

Hans Coper, Cup on Foot with Central Disc (1965).

Clay is not a craft material but an authentic medium for sculpture. The works take myriad forms, in concept scale and meaning: the continuing exploration of the vessel form, fusing the languages of painting, sculpture and architecture in a physical language of its own, is balanced by works concerned with the ironical re-presentation of ceramic traditions; with figuration; with landscape (physical, mythological, metaphorical); and with identity.27

This constituted the strongest statement yet, for British-based makers at least, in support of the full plastic potential of clay. Margetts advocated for clay as a fine art material that should be respected in its own right; that is, if respect meant being freed from craft association. Indeed, Margetts even suggested that Hans Coper had now joined Bernard Leach on the reject pile for contemporary makers.28 Yet, by erasing the craft roots of clay, Margetts short-circuited her own argument. Instead of agitating for the artistic virtuosity of all makers, she instead implied that only those who use clay as ‘an authentic medium for sculpture’ might transcend association with craft. What was meant by ‘sculpture’ was not explained. Such a position seemed to reinforce rather than deconstruct the art/craft dichotomy which, as the American jeweller Bruce Metcalf observed in 1997, was ‘as if the two worlds spoke mutually incomprehensible languages, with no Rosetta Stone to establish translation.’29 Yet, many of the works included in the exhibition by the likes of Gordon Baldwin, Alison Britton, Ken Eastman, Bruce McLean, Carol McNicoll, and Grayson Perry (to name just a few), were contingent upon audiences recognising how ‘craft ideas’, especially derived from domestic utility (that is, the pot), were being reframed in new ways. It was not that ceramics had escaped its ‘craft’ roots; nor was it as simple as reclassifying ceramics as ‘fine art’. Indeed, the art/craft divide had been produced for ideological and economic reasons; arguing for pottery as a separate fine art practice simply reinforced the division. It was more that there was a recalibration of ceramics as an expressive material in its own right and on its own terms. The history, languages, demands, and predilections of ceramic forms were interrogated, but only to proliferate interdisciplinarity. To situate this expansion within a centuries-old craft/art dichotomy might have critiqued Leach, but with hindsight it seems to have missed the point. Ceramics was being celebrated as its own medium; its plasticity enabled it to take what it needed from any other discipline, artistic or otherwise.

Janice Tchalenko, Platter (2016).(Courtesy of Luke Tchalenko)

Even today, to suggest a move beyond the art/craft dichotomy risks being contentious. As Greenhalgh has observed of craft, ‘the further it consolidated into classification – the more it became a naturalised and institutionalised signifier of a certain range of practices and attitudes – the less of a serious player it became.’30 Indeed, as Tanya Harrod noted, by ‘the 1980s […] the word craft became a positive hindrance’.31 Nevertheless, ‘Craft’ is an important word for many ceramicists, especially for those who trade in pots. Yet, an important definition of the word ‘craft’ is connected to skill; the myriad techniques of making, the ability to allow material to behave as itself, to compel it to take another turn, anticipate, or allow for surprise. Does craft define ceramics? No. It is true that ceramics is a technically complex discipline, and that these skills developed across history – so often lacking in fine artists who work in clay with little technical mastery – remain essential. Yet the fine arts – be it drawing, painting, or sculpting – also requires disciplinary craft, which must be mastered if a professional career is to be sustained. If fine art has ‘craft’, it follows that craft can also have ‘fine art’. By ‘fine art’, I mean – in the Kantian sense – beauty, aesthetic pleasure, and personal expression. After all, Bernard Leach may have emphasised the importance of utility, but this did not preclude pots from becoming a vehicle for beauty. In fact, artistry was central to his ethos. As Leach observed in The Potter’s Challenge from 1975, ‘technique can be a good thing but not by itself.’32 Leach insisted that pots should be beautiful, truthful, and individual. Above all else, he stated that ‘the final word I would use as a criterion of value in the world of art, if I were reduced to a single word, would be the presence of life.’33 For Leach, ceramic works – if they are any good – are the product of both craft and art.

Why does this matter? It matters because the question of whether ceramics is art or craft has rumbled on for decades, and it continues to have marked consequences on the contemporary. Johanna Drucker has convincingly argued how contemporary sculpture is dependent upon affect (the redeployment of materials into new contexts) and entropy (how conventional uses of material are eschewed).34 In particular, she suggests that:

Affectivity and entropy are intensified gestures of differentiation. Each defines a contemporary world of production and consumption that allows visual art to distinguish itself from mainstream consumer and material culture while still engaging with its very means. Rather than defining art as an entirely separate domain, affectivity and entropy suggest that fine art is a use, a way of working, a gesture of distinction, within the realm of material culture and of its objects, things, and stuff.35

In the contemporary period, such affect/entropy is often dependent on non-expert uses of material. In the case of ceramics, the affect of clay is aligned with the relative technical inexperience of the fine art artist, which is highlighted as a method of achieving authentic entropy. This means that ceramics in art must be distinguished from any association with its roots in craft (as argued by Margetts). The latter, in its mass-produced iterations, is deeply embedded in the material culture of the everyday. Tableware, for instance, is a product of, and literally a tool for daily consumption. By circumventing association with craft, clay can achieve authentic fine art entropy, legitimising it as a distinctive practice in the age of digital proliferation and mass manufacture. This is one means of accounting for the growing ubiquity of clay in the holdings of the contemporary fine art gallery, as well as the admittance of Grayson Perry into the world of fine art via the 2003 Turner Prize.

Given the above, it is not surprising that some trained contemporary ceramicists have chosen to downplay their skill (craft) so that they can exhibit a similar entropy as their fine art colleagues. As artists who have comparatively little technical understanding of clay occupy more and more space in fine art galleries, several trained ceramicists call themselves ‘fine artists who happen to use clay’, as though their choice of medium were a stumbled-upon accident. This is despite their advanced technical capability, and the fact that their work knowingly draws upon multiple aspects of ceramic history. Thus, the perceived difference between clay as ‘craft’ and ‘art’ material continues to have genuine impact on the careers of makers.

Astonishingly, Peter Dormer, writing twenty-five years ago, observed the same trend. He noted that although craftspeople:

have many understanding admirers, they have not found themselves admired as much as other ‘artists’. Potters do not earn the same regard as sculptors, for example […]. The contradiction is that it appears to many intelligent craftspeople that they have to renege on craftsmanship to pursue their craft. The admirers of ‘high art’ are not interested in craft and the consumers of decorative objects and other trophies for the home do not see that high craft is really worth paying for. So what is a maker to do if he or she is to gain status and earn a living?36

Is this denial of the word ‘potter’ simply produced by what the ceramic dealer, critic, and historian, Garth Clark polemically described as an ‘ego-driven envy […] fueled by resentment that craft, while successful, was not as respected or as valued as the fine arts’?37 Certainly such resentment persists in some quarters, though as many of the chapters in this volume evidence, the histories of ceramic production – understood as craft – are now being readily interrogated as part of studio pottery, and even circulated in fine art galleries. Nevertheless, as Clark suggests, as long as ceramics is seen to respond to fine art rather than vice versa, it will always be regarded as a discipline of secondary value.38 Will this lingering sense of ceramic entropy lead to the ecstasy of new disciplinary value, or the gradual atrophy of skill?

Towards definitions

If it is to reach the former, echoing Clark, and responding to Greenhalgh’s observation that the meanings of ‘craft’ have been subject to constant revision, criticism needs to play its part in documenting how ceramics is a vibrant and exciting interdisciplinary field of enquiry of and for itself. That means, to paraphrase Leach, finding the right language to evidence how ceramics is a field teeming with ‘life’. In the catalogue for his curated exhibition Pandora’s Box (1995) for the Crafts Council, Ewen Henderson (1934–2000) highlighted the significance of form as a central question. Selecting work for exhibition by makers such as Ian Auld, Gordon Baldwin, Bryan Illsley, Mo Jupp, Gillian Lowndes, Lawson Oyekan, Sara Radstone, and Angus Suttie, Henderson argued that ceramics demands ‘a formal language, and we all have to have it I’m afraid. We can’t converse without a verbal language and it’s even more important in the visual language because people are less familiar with it.’39 The pot, of course, remains central to this language.

But if considerations of utility are totally removed, is a pot still a pot in formal terms? What is the ‘essential potness’? Are pots and vessels really the same? If not, where does one end and the other begin? Is one art and the other craft? There seems to be a problematic lack of precision about the language of ceramics.

Two years before The Raw and the Cooked exhibition opened, the critic John Houston published The Abstract Vessel: Ceramics in Studio in 1991. This short monograph was an attempt to give conceptual classification to the growing plurality of approaches towards ceramic form. For Houston, historicism was not enough; it was not simply that artists were returning to the ancient roots of pottery where aesthetic divisions between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ did not exist. Rather, he sought to analyse instances of contemporary work that demonstrated ‘matters of stance and articulation where the artist’s voice and the potter’s form do not quite match; where the language is vivid but not entirely pottery-compatible: not authorized by pottery past.’40 In sympathy with Margetts, Houston suggested that the disassociation between clay and craft was where ‘the abstract vessel begins to be reinvented, made up, re-filled with more than the usual concerns of pottery.’41 The ‘abstract vessel’ was thus the synthesis (preferably somewhat awkward) of pottery with non-pottery concerns. The results, Houston suggested, were ‘abstract vessels certainly, but so rich in metaphors and analogies that our mental contexts are figured with a montage of kindred inventions, constructions, fictions – object-poems improvised in a cluster of tongues.’42 Certainly ceramic objects can be poetic in the sense that they have a self-reflexivity beyond utility; Alison Britton had already argued this in her essay in The Maker’s Eye in 1982, quoted earlier. But what does this reveal about the use of form?

Houston’s recognition of the self-reflexive interdisciplinarity of ceramics remains astute, but there is something of a lack of precision in the term ‘abstract vessel’. His analysis includes figurative sculptures by Philip Eglin, where, Houston argues, ‘the image of the body as the prime analogy of a form to render feeling is what transforms the abstract vessel into the thinking object.’43 Yet, this expansive belief that figurative sculptures are abstract vessels, presumably because they contain space, effectively places most, if not all, non-functional ceramics into the formal sphere of the vessel. Eglin’s work sometimes takes the form of a reconfiguration and innovative treatment of British ceramic history. Not all of his output relates to the pot, however, especially those works that explore figuration. These are ceramic sculptures. One of the issues with Houston’s essay is that he uses the words ‘pot’ and ‘vessel’ interchangeably, making the notion of the ‘abstract vessel’ remarkably abstract.

In moving beyond the abstract, dictionary definitions offer an intriguing point of departure:

Vessel (noun)

A container, especially for liquid; a ship or large boat; a tube or duct for carrying liquid, e.g., blood or sap, in animals and plants.

Pot (noun)

Any of various domestic containers, usually deep round ones, used as cooking or serving utensils, or for storage.

Chambers Dictionary

From this, it is possible to deduce that pots are associated with domesticity and function, whereas a vessel is somewhat more expansive in form. Vessels comprise sculptural decisions that consider interior space as a question of containment; in particular, how interiority is confined by, and then released into, the exterior. This means that vessels have no overt relationship with the form of domestic pots. Pots may consider similar territory, but they have the additional frisson of filtering such sculptural investigations through forms associated with domesticity and utility, even if such associations are denied, or become replaced by other metaphorical resonances. It does not mean that functional pots are craft and non-functional ones are art; more that the emphasis on the self-evident, reflexive (poetic) nature of artistry is, as is always the case, dependent on the maker’s own agenda, and how the end user chooses to deploy the object (that is, admire it on a shelf, use it, or both).

One might legitimately ask: why not simply call any pot that is sculptural and non-utilitarian a vessel? ‘Vessel’ certainly sounds grander than ‘pot’. Indeed, some might feel that the description of work as a vessel helps to initiate the perceptive labour required from audiences, specifically recognition that there is more at stake than questions of utility. The problem here is that, at a fundamental level, all pots sculpt space, and a great many of the makers included in this volume make maximum use of this aspect in their work. There is, therefore, a risk that conflating ‘sculptural pot’ with ‘vessel’ diminishes the significance of form – especially the pot – and the development of precise ceramic languages.

In her essay for The Raw and the Cooked, Alison Britton (who refers to herself as a potter who makes pots) suggested how a pot can be:

a form that is overtly hollow and frequently curvaceous, with a related interior and exterior appearance, [that] can very easily seem to be a metaphor for the human body or self. More angular geometric pots seem to relate to buildings, and perhaps sleights of scale and to an architectural sense of space. […] More loosely amalgamated, highly fused, and geological-looking pieces readily make suggestions of landscape, prehistory, and forces of nature.44

Britton’s definition highlights the interdisciplinary nature of pots. Pots can, and do, bridge formal connections between notions of utility (craft), decoration, painting (art), the technical history of ceramic production (craft) and contemporary sculpture (art). A pot is a form that can be pulled in multiple directions; one of its strengths is its malleability. Smuggling the formal language of the ‘pot’ into the ‘vessel’ risks denying the adaptation, extension, and individualisation of the formal languages of pottery that give a piece its significance. The vocabulary becomes obscured.

The remedy demands a significant shift in paradigm that runs counter to contemporary understanding, and even runs counter to several of the makers included in this book. The word ‘vessel’ is not automatically interchangeable with the word ‘pot’. Rather, as the dictionary definition suggests, a vessel is a somewhat looser term; it is not anchored to forms associated with, or developed from, domestic utility but can float (like a sailing boat) on its own formal buoyancy. A vessel does not reference forms found in the domestic frame; it need not have the expansive curvaceousness and hollowness that Britton observes. Rather, it playfully arranges internal and external space into dynamic relational contours without recourse to the pot. Admittedly, a curvaceous pot is one means of exploring the relations between interior and exterior space, but importantly for the point being made here, it is not the only one. Tubes, for instance, are a recurring motif in vessels, perhaps a referent of blood vessels, which they nominally resemble. Once it is regarded as distinctive and independent from the pot, the vessel is a remarkably under-explored ceramic form. In Britain, some, though by no means all, examples of work by Gordon Baldwin (his boulder-inspired vessels), Sara Radstone (her boat-inspired caskets) and Lawson Oyekan – as outlined in the chapter on his work in this book – indicate the directions in which the vessel might be taken. To call these ‘pots’ is to distort what they really are.

Is it not the case, then, that a vessel is simply a kind of ceramic sculpture? Yes and no. Sculpture, as Laura Gray has appositely noted, is a nebulous term, capable of absorbing many of the contradictory approaches attributed to it. Indeed, as noted above, the three-dimensional quality of most ceramic work classifies it as ‘sculptural’, so what differentiates either the pot or the vessel from ceramic sculpture? Gray suggests that, despite its inherent complexity, ‘form, space and material remain important for thinking about sculpture’.45 Thus, if a pot has a curvaceous hollowness associated with (or derived from) utility, whilst a vessel uses other vocabularies to consider the flow between interior and exterior space, then – in another shift of paradigm – a ceramic sculpture emphasises exterior surface via an enclosed form. To reiterate the critique of John Houston’s abstract vessel, a Philip Eglin figure is not a vessel, it is sculpture; sculpture that is formally different from a sculptural pot (for example, by Elizabeth Fritsch), and further different from a sculptural vessel (for example, by Gordon Baldwin).

It is important to point out that one form – sculpture, vessel, pot – is not worthier than another; they are simply different. Yet in acknowledging difference, there is perhaps the temptation to overstate them when they are by no means absolute. It is the job of artists to undermine formal categorisation at every turn. It is perhaps better, then, to consider these categories as having degrees of overlap, as operating on a continuum or sliding scale, where each work configures attributes of form into distinct kinds of dynamic relationship (see the diagram, The Continuum of Ceramic Form, for the principal arcs that might amalgamate categories). Much contemporary work hovers on the outskirts of, or sits across, categories – as pot-sculptures (perhaps the most common form described in this book) or vessel-sculptures. Theoretically at least, a work might even exhibit qualities of the pot, the vessel, and sculpture as resolved elements in the same complex composition (see the central axes across the shaded centre in the diagram below). Do these categorisations, and the attribution of a sliding scale, risk pushing analysis into subjective speculation? Perhaps. Yet, it is clear that ceramicists, whether they label themselves as potters, makers of vessels, or sculptors, do move between and across different points of reference. My previous book, Contemporary British Ceramics: Beneath the Surface, was testament to this interdisciplinarity. As a natural extension of that project, forging a means to discuss movement across vocabularies of form is important, not only for the coherence of this volume, but also for the clarity and confidence of ceramics as a discipline.

Millennium Cup (1999), a sculptural pot (left), and Study for a Large Blue Vessel (2002), a vessel (right) by Gordon Baldwin.

A pair of vessels by Sara Radstone, Untitled (2002).(Courtesy of Sara Radstone)

A ceramic sculpture by Sara Radstone, Dark Folder (2012).(Courtesy of Sara Radstone)

The Continuum of Ceramic Form: the principal axes between pots, vessels, and sculptures.

The structure of this book

Given the above, it is clear that the structure of this book cannot follow the obvious format, namely the neat sub-division of chapters into potters that make pots, those that make vessels, and those that create sculpture. Such a categorisation might offer a satisfying straightforwardness, but it would be, quite simply, wrong. The pottery landscape does not work to such neat coordinates. Indeed, most chapters include examples of work that demonstrate how a potter moves between vocabularies in their work. The chapters that follow document how the languages of the pot, the vessel, and sculpture are (re)configured and (re)combined in the work of contemporary makers.

That said, where work is described as a vessel by its creator, that chosen term has been honoured in the writing. Some may feel that this undermines the ideas outlined in this introduction, and risks adding to the confusion. Personally, I feel it accurately reflects current ambiguity in describing ceramic form. If readers look at the terminology attributed to work more critically, this introduction will have achieved its aims. Further thoughts offered in the Afterword may also assist the discussion.

The chapters of this book can be read independently and non-chronologically. Yet, as reflected in its subtitle, Forms of Expression, the volume seeks to comprehend what is at stake in the decisions that have been made around form – the actual means of expression. For this reason, the volume is divided into six broad thematic sections, which highlight the central concerns of the potters included and facilitate comparisons between them. The first, Formal Languages (Chapters 1–3), introduces a methodology for the analysis of form inspired by Bernard Leach who, in A Potter’s Portfolio first published in 1951, outlined the compositional structure of a pot. It emphasises how the constituent elements of form become utilised as an essential vocabulary for creative expression in contemporary work.

As noted earlier, William Staite Murray offered an alternative vision to Leach, aligning ceramics with the expressive plasticity of fine art. Dialogues with Twentieth Century Art (Chapters 4–8) presents four contemporary makers whose work might regarded as further developing Staite Murray’s belief in the painterly and sculptural possibilities of the pot. Comparisons with Cy Twombly, Josef Albers, Barbara Hepworth, and Ben Nicholson are made not to imply the secondary status of pottery, but to evidence how pots exhibit equivalent decorative and sculptural expression through their own formal languages.

The third section, Dialogues with the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Chapters 9–14), surveys a branch of the turn towards the postmodern that combines contemporary art with pre-Leach ceramic mass-manufacture and the circulation of its display. By drawing upon the aesthetics of Wedgwood, Spode, and Sèvres, these makers also offer a range of capital ‘P’ and lowercase ‘p’ political statements: from the denial of Britain’s colonial past to a direct confrontation with it, and from the definition of studio pottery as necessarily ‘handmade’ to the embracing of the latest 3D printing technologies.

Pottery is, of course, concerned with tactility – the pressure of the fingers on wet clay and the touch of hands on fired objects. The fourth section, The Tangible (Chapters 15–17), explicitly focuses on the relationship between potter, pots, and purchaser, arguing that the pot is a singularly tactile vehicle for interpersonal connection. In contrast, The Intangible (Chapters 18–21) investigates how pottery expresses the ethereal, spiritual, and hypothetical, from the emotional landscape of the interior to the scientific theories that explain the laws of the universe. The final section, Colliding Worlds (Chapters 22–24), demonstrates how pots can reflect upon, and critique, our relationship with the natural world. Challenging the stereotype that pottery is simply a quaint and complacent activity, these works coalesce to warn us of the consequences of our ecologically unsustainable craving for natural resources.

The rationale for selecting who to include in this book was – as it always is – a personal one. For each potter I chose, I could easily have included another three. Nevertheless, as was the case with my previous volume, I have sought to include a mix of established, mid-career and emerging artists. Some of the potters are very much a product of the last decades of the twentieth century, but they form part of the contemporary ceramic landscape that connects the achievements of established generations with the evaluative concerns of the up and coming. In this sense, the volume represents a snapshot of a specific moment in time.

With this in mind, it must be asserted that the focus of this book on Britain does not infer that only British, British-based, or British-trained ceramicists undertake formal creativity, or that they automatically lead the world in their discipline. To spotlight Britain is simply a means to focus the discussion via the specific geographical context in which I live. Wherever possible, I meet the potter in their studio and discuss their work with them, and a focus on Britain is conducive to this process. No kind of ceramic neo-imperial British greatness, or post-Brexit superiority, is implied. All of the potters included were either born, currently live, or were trained in Britain. Beyond this, geography is irrelevant. Indeed, as the first chapter on the work of Magdalene Odundo attests, pots will always transcend boundaries.

Magdalene Odundo: Glossolalia

In my own work, my vocabulary is deliberately minimal. I do not want my pots to require lengthy explanation. I want them to feel empathetic, I want people to be able to understand them visually. For me, visual literacy, looking and noticing, is the most important thing. Viewers are welcome to imbue the work with whatever they want, but the words come second. The work, the vessel, must come first.46

To mark the end of the twentieth century, Dame Magdalene Odundo OBE produced a series of Millennium Jugs (as well as Millennium Cups) in white earthenware. Such unassuming domestically scaled pots might appear a curious introduction to the grander terracotta forms for which Odundo is internationally recognised. Yet, I begin with these inventive works because they exemplify key concepts that can be discerned elsewhere. The jug itself is formed with a rounded base and cannot stand by itself. A separate concave foot affords it a supported place to rest. Consequently, the jug can – if desired – be manipulated to stand at obtuse angles from its base, to tilt so that the symmetrical balance of the jug is disrupted. This interplay between symmetry and asymmetry is, as Emmanuel Cooper pointed out in his excellent assessment of Odundo’s oeuvre, a central compositional concern in much of her work.47 More significantly, as a piece made to commemorate the millennium, the jug points in two directions. The extruded handle curves away from the body in an upward direction, whilst the extruded ‘spout’ curves downwards away from the lip. The body of the jug is thus located at the interstice between these directions, redolent of the move between centuries, and symbolic of looking both backwards and forwards. Setting the jug into its base at one angle or another (either towards the handle or, conversely, towards the lip) implies a leaning towards history or the future, whilst the jug positioned upright (as photographed) emblemises attenuation to the present. Thus, the jug is a container of uncertainty and anxiety around moments of passage from one epoch to the next. The inability of the jug to stand without its concave base might even symbolise our need for rituals, and associated objects, to ground us during periods of transition.

Millennium Jug (1999).

Millennium Jug (1999) alludes to the wider liminality of Odundo’s work; how it sits in and out of time. In museums, her pots blend effortlessly with examples of ancient ceramics from Africa or South America. Out of an interminable desire to comprehend the expressive potential of clay, the cultural and religious significance of pottery across thousands of years, pursued through decades of study, exudes from her fingertips. Yet, in the contemporary art gallery, Odundo’s work commands its own presence and her instantly recognisable pots are internationally sought-after. Her forms curve across continents in every sense; she fashions visual patchworks that situate the present within the past and enmesh the present into the future. As with the Millennium Jug, her pots are Janus-faced, looking backwards and forwards from their own temporality.

It is, however, axiomatic that pots transcend linguistic, religious, and cultural specificity. A look around the ceramics collection of any museum confirms this. What risks the prosaic becomes, in Odundo’s hands, perceptive and enriching. Her emphasis on visual literacy implies an understanding of how the personal moves into the universal and back again. The perceptions of the artist are cast in the primordial visual language of clay for universal comprehension, but meaning is not a given; it is always context-specific, being inflected – accented – with a particular syntax in the moment of experience. Pots may possess a universal visual language, but meanings shift, are revised, or re-inscribed. Odundo challenges us to read visually. Interpretation comes later. But what is it, exactly, that we are being asked to read?

A clue to this lies in Odundo’s early ceramic training. Born in Kenya, Odundo travelled to England to study at the Cambridge College of Art from 1971–73, and then the West Surrey College of Art and Design in Farnham from 1973–1976, where Henry Hammond (1914–1989) was the Head of Ceramics. Hammond, whose aesthetic was derived from Anglo-Orientalism, took his students on field trips, including to St Ives, where Odundo and her fellow classmates had the opportunity to meet Bernard Leach in 1974. Soon after, following a meeting with the Leach potter Michael Cardew (1901–1983), Odundo learned of the Abuja pottery that Cardew had himself set up in Nigeria, and travelled there to study for a few months in the summer of 1974. Then, in 1976, Odundo travelled to California and was able to see the Native American potter Maria Martinez (1887–1980) at work.48 Even from this brief summary of Odundo’s activities in the early years of her ceramic education (she later went to the Royal College of Art from 1979–1982), there is an obvious fascination with the transnational movement of potters, potteries, and pots.

It is no coincidence, then, that Odundo found sympathy with some of the internationalist and universalist ideas of Bernard Leach. As Odundo herself stated:

Coming from a family where, for my dad, travelling had been a part of work, it seemed that Leach was describing a very enriching culture. […] I thought the philosophy Bernard Leach was advocating, which I understood to be about being engaged in making objects or making art, was sound and relevant.49

Leach was a believer in the Bahá’í faith, a syncretic religion dating from the nineteenth century that seeks the realisation of a divine cosmopolitan world order. As Leach himself wrote, Bahá’í promised a unified world via:

principles of independent investigation, […] unity, […] roots in justice, universal education, balance of religion and science, marriage of East and West, recognition of art, of the equality of men and women, the need of a common language, the abolition of both great wealth and great poverty, and, to these ends, of a universal parliament of man [sic …].50

The cosmopolitanism of Bahá’í provided Leach with a philosophical and spiritual means of reconciling himself with his own sense of hybridity. Born in Hong Kong, and spending much of his life moving between Britain and Japan (and elsewhere), Leach recognised that Bahá’í offered a rationale for his practice, which ‘was inextricably becoming rooted to two hemispheres’, and that he considered placed him as ‘a courier between East and West’.51

In A Potter’s Portfolio, first published in 1951, and which was then subsequently edited into The Potter’s Challenge, first published in 1975, Leach sought to expound upon the ability of pottery to communicate universally:

The pot is the man [sic], he a focal point in his race, and it in turn is held together by traditions imbedded in a culture. In our day, the threads have been loosened and a creative mind finds itself alone with the responsibility of discovering its own meaning and pattern out of the warp and weft of all traditions and all cultures. Without achieving integration or wholeness he cannot compass the extended vision and extract from it a true synthesis.52

To provide a sense of how this synthesis was achieved, Leach included numerous examples of ‘Exemplary Pots’ which, aside from a few examples from Ancient Greece, America, and the Middle East, came from East Asia. To introduce these ‘Exemplary Pots’, Leach included diagrammatic analyses of two Chinese Song dynasty (960–1279) works: a vase and a bottle. The analysis of the vase, reproduced here, divides the form into different ratios, some documenting lines of correlation between the base and the rim, others exploring how compositional spheres exert control over mass and volume. By placing these illustrations before the reproductions of ‘Exemplary Pots’, Leach was clearly encouraging the reader to apply these ideas across the illustrations, and by extension, to their own practice.

Analysis of a Song Dynasty Vase by Bernard Leach.(Reproduced by kind permission of Profile Books)

In turning towards Odundo, it would be easy to overstate her connection with Bernard Leach’s philosophy. Her relationship to Leach should be regarded as a general, if critical, sense of compatibility; Leach never taught Odundo. Nevertheless, in some of her work from the early 1980s, there is a stylistic fusion of form inspired by Abuja pottery and the black burnished pots of Maria Martinez. In the example reproduced here, Odundo has carved into the top section of the pot, creating a spherical pattern that both alludes to and disguises some of the compositional elements discerned by Leach. She has positioned the lines as being lower than – in parallel with, rather than as actual markers of – the ‘major sphere’ of the pot. This gives the feeling that the upper and lower sections are exerting pressure on one another, affording the work a dynamic presence despite its apparent simplicity.

Angled Mixed-Colour Piece (1989).

Stages in the analysis of Angled Mixed-Colour Piece (1989).

Angled Mixed-Colour Piece (1989) with lines of analysis. The numbers relate to points in the preceding text.