15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

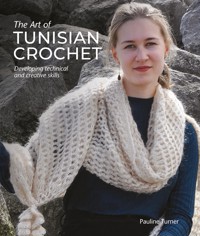

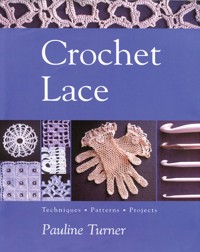

Crochet Lace is a practical guide to crocheting with fine thread to produce beautiful and delicate lace designs. Whether you are a crocheter or a lacemaker, you'll find plenty to interest you in this book. It explores the most popular styles of crochet lace in depth, with historical information, useful techniques, individual patterns and larger practical projects, such as framed lace motifs, pretty gloves and a bedspread. Illustrated throughout with colour photographs and easy-to-follow diagrams, Crochet Lace is a valuable sourcebook for everyone who wants to learn how to make lace with a crochet hook.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 184

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Crochet Lace is a practical guide to crocheting with fine thread to produce beautiful and delicate lace designs. Whether you are a crocheter or a lacemaker, you'll find plenty to interest you in this book.

It explores the most popular styles of crochet lace in depth, with historical information, useful techniques, individual patterns and larger practical projects, such as framed lace motifs, pretty gloves and a bedspread. It includes:

• The Basics: all the basic equipment, materials and techniques for crochet are covered, so you can start making crochet lace even if you have no previous experience of the craft.

• Filet Crochet, the most popular kind of crochet lace, results in a smooth, uniform appearance. All the techniques are given, plus charts for classic patterns, including Van Dyke bricks and hearts.

• Motifs: from the much-loved Granny Square to more intricate wheels and flowers, motifs play a large part in lace crochet. A library of twelve of the best designs is included here.

• In Irish Crochet, motifs are made first then connected by a background network of lace stitches. This chapter gives traditional and modern patterns, including shamrocks.

• Learn to imitate traditional types of lace, such as Honiton lace, guipure lace and tatting, using crochet.

• Edgings: adding a crochet edging is a great way to personalize your clothes. This chapter explains how:

• Adaptation and Finishing: how crochet can be adapted for clothing and household items, including instructions for making braids and buttons.

Illustrated throughout with colour photographs and easy-to-follow diagrams, Crochet Lace is a valuable sourcebook for everyone who wants to learn how to make lace with a crochet hook.

Pauline Turner is the author of many books and articles on crochet, including How To Crochet, published by Collins … Brown, and runs an international correspondence course, the Diploma in Crochet, the first part of which has also been adapted for the City and Guilds in the UK. She is a founder member of the Knitting and Crochet Guild of Great Britain and is the International Liaison Chairperson of the Crochet Guild of America.

More Titles from BatsfordFounded in 1843, Batsford is an imprint with an illustrious heritage that has built a tradition of excellence over the last 168 years. Batsford has developed an enviable reputation in the areas of fashion and design, embroidery and textiles, chess, heritage, horticulture and architecture.

tap on the titles below to read more

@Batsford_Books

www.batsford.com

Contents

Introduction

The Basics

Filet Crochet

Motifs

Joining Motifs

Irish Crochet

Crochet Imitating Other Types of Lace

Edgings

Adaptation and Finishing

Index

A Note on Terminology

Introduction

With any craft there will always be confusion about its exact source, often because an idea beginning in one country will very quickly be available in another. As I looked back, searching for when crochet arrived in Britain, and as I tried to find the journey it made to get here, I realized that there was a conflict of opinions. On searching further it became clear that assumptions had been made that only served to confuse matters and that even basic definitions varied. For instance, some authorities were calling a process of making a textile by the name crochet when it had been worked only with the fingers, or had used a bar and fingers to make the loops. Sprang and finger knitting may look like crochet but I believe that including them under the banner of ‘crochet’ makes the definition of the term too large and unwieldy. I realized I needed a starting point for myself.

I began looking in dictionaries and encyclopedias to see how they described crochet. There was very little to choose between them. The entry in the Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, which I felt gave as concise a definition as any, states that crochet is ‘looping work done with a small hook’. Nowadays, the word ‘small’ is unnecessary because crochet can employ huge hooks on which to work rug wool and very thick string. However this book focuses on thread crochet and therefore the word ‘small’ is appropriate.

Originally crochet used fine cottons in an attempt to copy the designs of traditional lace. Small hooks with tiny barbed heads were required to manipulate the threads. After the First World War, ladies started to use thicker threads for crochet work and also fine knitting yarns for greater speed. When rayon was introduced, which split when knitted, it was found that a slightly larger crochet hook worked well with it.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s new crochet techniques were explored, as was the use of materials other than traditional cotton and linen threads. It was then that the range of hook sizes was greatly expanded. Since the 1980s, the variety of hooks has extended further, with increasingly larger sizes being produced to allow thicker wool such as rug wool, baler twine, acrylics and rag strips to make a variety of useful and decorative articles. Ribbons, wire and even toilet paper can be used for crochet.

However, there is still a lot of speculation over where and when crochet was developed. Part of this confusion occurred because it was frequently linked with knitting, and therefore erroneous assumptions were made that crochet is as old as knitting. If this were true and if, as seems likely, the craft of crochet started on the continent of Europe, it seems very strange that there are no paintings or writings describing crochet – particularly as there are paintings of people knitting. Large numbers of beautiful Renaissance paintings show ladies making lace with bobbins on a pillow or with the needle, but none show them crocheting. A rare reference can be found in Mary Thomas’s Knitting Book when she describes the way the shepherds of Landes in southern France produced knitting using hooked needles made from umbrella ribs. However, the South American natives also used hooked needles with which to knit, not crochet.

The Great Exhibition of 1851, held in London, was famous for exhibiting crafts of all kinds. What is fascinating is the large number of entries in all needlecraft sections except crochet. In fact, the crochet section was included under embroidery. This is another factor indicating that crochet is the youngest of all the needlecraft textiles, and confirms my understanding that crochet originated from the craft of tambour embroidery, the tambour hook evolving into the crochet hook. The majority of the exhibits came from central and southern England with single exhibits from Ireland and Liverpool and two from Yorkshire. Each time I find a date for a piece of crochet it confirms that the craft spread from the Continent north, east and west. It also indicates to me that crochet was not as widespread as it is sometimes said to be.

As I went through the Great Exhibition catalogue I was intrigued to notice that Cornelia Mee had exhibited many pieces of needlework but did not include any crochet. Considering Cornelia Mee was a prolific producer of crochet patterns during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, I find it fascinating that she had not discovered the crochet (or tambour) hook at this point in her creative career.

Entries from the catalogue of the Great Exhibition of 1851:

Riego de la Branchardaise, Eleonore, London Inventor and manufacturer exhibiting lace berth, altar cloth, prayer book covers, collars.

Clarke, Eliza, Norwich Collar in point stitch with crochet edge representing guipure lace, crochet collar imitating Brussels point lace, collar imitating guipure lace.

Constable, Hannah, Clonmel, Ireland Infants’ dress in white thread crochet.

Cross, Mary, Bristol Crochet counterpane.

Fryer, Miss N., Barnsley Crochet counterpane.

Lockwood, Georgiana, London A child’s fancy crochet frock. Crocheted toilet cover.

Padwick, Anne, Emsworth Crochet table cover in Berlin wool. Wool toys, tea service.

Thwaites, Mary, Islington Crochet D’oyleys.

Waterhouse, Emma and Marie (no town listed) Crochet counterpane in Strutts cotton.

Hooks manufactured for use with fine work produced in the last century and the early part of this century were made to look like those used in tambour embroidery. This tool is shaped like a stiletto with a fine, often very sharp, hook on the end. The tension (the evenness of the looped stitches) had to be achieved by making certain that the loop under construction went to exactly the same point along the length of the hook each time. Normally this was achieved by placing a finger on top of the stem of the hook to act as a stop. It also meant that in the earlier days of crochet, one hook could be employed for different tensions and different thicknesses of fine thread just by moving the finger used to create the stop to a different place on the hook.

Throughout this book I have defined crochet as a means of producing a textile using a hook. In order to make anything in crochet it is necessary to have one loop on the hook at all times. No matter how complicated the crochet stitch or pattern construction is, it will start with one loop on the hook and end with one loop on the hook in readiness for the next stage.

When following post-1970 crochet patterns requiring the use of 2.0mm (size 4) hooks or larger, the loops should be the size of the circumference of the hook’s stem. As hooks manufactured since that date have straight stems with an even diameter throughout, this is an easy rule to follow. Obviously there is shaping near the barbed head and the tension will change if the crochet worker places the loops in that part of the hook instead of on the regular part of the stem.

Left: A selection of old crochet hooks. Centre: A selection of new crochet hooks. Right: Antique pieces of crochet lace.

Crochet patterns

Printed crochet patterns did not evolve in a natural way but came into being through consumer demand. The very first patterns were actual samples of crochet that were copied, often working on from the crochet sample itself.

Initially the names of the stitches were either translations from European languages or referred to the style of lace that was being copied in crochet. In the beginning the term ‘crochet en air’ was used to distinguish the crochet textile from the hook employed for tambour embroidery, because both involved a tambour style of hook. However, while tambour embroidery produced a design composed entirely of chain stitches that were anchored through a piece of fabric, ‘crochet en air’ produced the chain stitches free from any other material but also attached to those chain stitches previously made. This was probably the birth of crochet lace. Assuming that my premise and research findings are correct, this would be the reason why crochet was listed in the embroidery section of the 1851 Great Exhibition catalogue. Filet crochet, which is a technique of crochet that copies the needle lace of filet, retained its name, probably because it was the kind of crochet most frequently worked.

During the 19th century information about crochet appeared in needlecraft books by prominent authors such as Mlle Riego and Mrs Gaugain, to name but two. Mrs Gaugain called all her crochet work ‘tambour’, however all the main writers of the mid-nineteenth century used different terminology for the same process. The lack of consistency in naming crochet stitches and crochet processes persisted for a century. The names of the stitches did not matter until the latter half of the 20th century because instructions for any design were rarely given – the crochet pattern was either copied from the actual crochet or, in the case of filet crochet, from charts. Books written between 1850 and 1880 with patterns given in words were all accompanied by clear illustrations showing where the stitches lay, usually with a sketch. If ever you can get your hands on some of these old patterns, you will find them great fun. Each row or round of instructions constituted an essay, as most writers did not use abbreviations until much later. The secret is not to get lost in the reading while trying to follow the instructions.

Old pattern giving lengthy instructions.

By the mid-nineteenth century, although the number of stitches and combination of stitches worked was small, they formed a wide variety of designs. These designs would have small examples kept in fabric books. An actual piece of crochet was worked as a pattern reference and stitched on to either oiled cloth or heavy-duty felt. The book would then become a communal pattern book of crochet designs for a small hamlet or community. If someone ‘invented’ a new design by playing around with stitch combinations, they would add a sample to the pattern book for the rest of the hamlet’s inhabitants to copy. At this stage most crochet designs were lacy, which meant it was easy to copy the flat, open pattern by counting the number of stitches in each row or round.

Old pattern showing obsolete abbreviations.

By 1950 the names of the basic stitches printed in patterns within the United Kingdom had been standardized, as had their abbreviations. However, the United States decided to change the naming of their stitches from 1912 until as late as c. 1936. Until that time the USA used the same terminology as Britain. Now they name their stitches with the same names but for different techniques. Confusion, confusion. Many designs produced in continental Europe when translated may use either British or American terminology for the names of the stitches.

Fortunately, the Continental patterns are nearly always accompanied by diagrams using the international crochet symbols. Because symbols and a chart are being followed it does not matter which language the pattern is written in.

Even by 1850 most working-class women could not read and write, although young ladies in the middle and upper classes were becoming accomplished in these tasks. Needlecraft skills were usually learned from governesses, maiden aunts, mothers or elder sisters. Girls were shown how to crochet and copy patterns, and not left to read and decipher instructions for themselves. This was an important factor in creating much of the confusion still existing within the craft of crochet. The crochet terminology and the patterns of the post-1950 period still use different names for very similar instructions.

Old pattern showing obsolete abbreviations.

It was not until after 1960 that crochet began to experiment with different yarns and different ways to insert the hook and genuinely look at the potential of crochet to produce many other techniques. Hence throughout the period 1850–1950 the stitches remained few and were easily copied.

It was only at the end of the 20th century that people around the world began to want a stable and uniform vocabulary for crochet. Students of crochet were encouraged and inspired to do serious research into crochet as a textile. I am fortunate to house a large number of their findings. The results are ongoing and as more and more people research the subject in a scientific manner, their conclusions continue to amaze. Where some of their findings cover the art of thread crochet I have included them in this book.

One other aspect of thread crochet that I have observed is the number of times the original lace copies appear in pattern books throughout the world. If you think you have seen a crochet pattern before, the chances are you probably have, either in a different kind of yarn or in a different country.

My conclusions

Summarizing crochet’s multi-faceted origins, I determined a number of points:

A young craft: crochet is the newest of the textiles using yarn and thread. In recent years it has begun to make a place for itself among the crafts and art forms, although it has been a struggle.

A pirate craft: originally crochet ‘stole’ its ideas from the lace makers and chose to make crochet fabric using implements from other crafts: crochet is a pirate.

Lace imitator: by using the embroiderer’s hook and copying the lace designs it was possible to make a fabric that was similar in looks to lace but one that could be made much more quickly. In this way crochet was able to become a cheaper version of a much sought-after trimming.

Copying itself: copies of filet lace designs became prolific, primarily because those who were adept at working with lace thread and a hook were often illiterate. There are many tales of ladies in service, working on farms, or doing other manual work, going into town on market day and memorizing as much of a filet-style crochet pattern as possible. They would crochet this at home and hope that the shop would not have removed the design they were working on before the following market day.

Home craft: crochet existed as a home craft long before it became incorporated into fashion or art forms. It is only since the 1970s that various people have begun to explore the potential of the different techniques required in crochet and to make use of the various combinations of stitches, yarns, hooks and colour blending to create new and exciting effects.

Confused history: searching for proof of the origins of crochet we can be sidetracked by eminent people informing us that fabrics do not last and that this is why no early samples survive. Often this is to confirm their own belief that crochet is an old textile, despite the fact that fabrics in other media such as weaving, knitting, sprang, and so on can be found.

Art and folklore: serious researchers will look to folklore and paintings for proof of the existence of a craft or husbandry skill. During the French Revolution for example, we see paintings of lace making, knitting, weaving, spinning, even tatting and knotting, but to date no painting of someone working crochet has come to light. Nor are there any known references to crochet in folklore.

Nuns’ story: Irish crochet is one of the few branches of crochet that has been well documented, by nuns, and even here the earliest reference to crochet is at the turn of the 19th century when the Ursuline nuns expanded their needlework and included crochet. The first Ursuline convent was formed in 1772 and was well known for its fine needlework. This has led people to believe, erroneously, that the nuns could crochet when the convent was opened.

Chapter OneThe Basics

The Basics

There are many ways of exploring the many different facets of crochet, but as this book concentrates on crocheted lace I have chosen to look at the traditional beginnings as well as the more usual present-day techniques. Should you already be an experienced crocheter, you might like to try out the following instructions, which were originally given in The Enquirer’s Home-Book, dated 1910. The passage begins with what was required to produce crochet work, and then goes on to tell you how. If you are a beginner to crochet, the following section is for historical interest only; please practise the methods given from page 19 onwards first, returning to these more complicated explanations when you feel more proficient.

‘… Cotton, thread [presumably linen], wool or silk and a crochet needle are the materials required for crochet work. The long wooden and bone crochet needles are used for wool, while for cotton and silk short steel needles screwed into a bone handle are best. The beauty of crochet work largely depends upon the regularity of the stitches; they must be elastic, but if too loose they look as bad as if too tight. The work should be done only with the point of the needle; the stitch should never be moved up and down the needle.

‘All crochet work patterns are begun on a foundation chain. There are three kinds of foundation chains. The plain, the double, the purl. The plain foundation consists of chain stitches only.

‘Plain foundation chain – Form a loop with the cotton or other material with which you work, take it on the needle and hold the cotton, as for knitting, on the forefinger and other fingers of the left hand. The crochet needle is held in the right hand between the thumb and forefinger, as you hold a pen in writing; hold the end of the cotton of the loop between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, wind the cotton once round the needle by drawing the needle underneath the cotton from left to right, catch the cotton with the hook of the needle and draw it as a loop through the loop already on the needle, which is cast off the needle by this means and forms one chain stitch. The drawing of the cotton through the loop is repeated until the foundation chain has acquired sufficient length. When enough chain stitches have been made, take the foundation chain between the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, so that these fingers are always close to and under the hook of the needle. Each stitch must be loose enough to allow the needle hook to pass easily through. All foundation chains are begun with a loop.

‘Double foundation chain – Crochet two chain stitches, insert the needle downwards into the left side of the first chain stitch, throw the cotton forward, draw it out as a loop, wind the cotton again round the needle and draw it through the two loops on the needle *draw the cotton as a loop through the left side of the last stitch, wind the cotton round the needle and draw it through both loops on the needle. Repeat from * until the foundation chain is long enough.

‘Purl foundation chain