9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

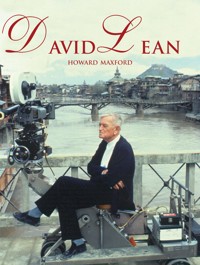

Oscar-winning director David Lean was responsible for some of the most enduring images in British cinema, including the romantic clinches between Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson in Brief Encounter and Pip's memorable dash across the marshes in Great expectations. Lean became renowned for his visual epics, painting the cinematic screen in such films as The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. Yet, despite the large canvas of these masterpieces, Lean never lost sight of the human story within them. In his study of Lean's career, Howard Maxford takes behind-the-scenes look at each of the director's films, chronicling their making and their subsequent reception by both audiences and critics. Lean's early work as a film editor, which led to his comission by Noel Coward to co-direct the landmark war drama In Which We Serve, is examined, along with Lean's self-imposed 14-year exile after a savage reception from critics to his penultimate film. His exile ended thriumphantly with the release of a Passage to India. Lean, the man away from the camera, is also revealed, including his six marriages and his strict Quaker upbringing. An informative critical guide, this David Lean companion offers a detailed examination of the work of one of cinema's true greats.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 335

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

DAVID LEAN

DAVID LEAN

HOWARD MAXFORD

CONTENTS

1 Croydon Days

2 First Steps

3 Cutting Edge

4 Lean Times

5 A Bit of French

6 Serving the Master

7 What Larks!

8 Ann

9 Katie

10 Bridge Building

11 It Is Written

12 Russia, Spanish Style

13 A Touch of Blarney

14 The Long Return to Triumph

15 Endgame

16 Filmography

‘He was the most extraordinary man I ever knew.’

From Robert Bolt’s screenplay of Lawrence of Arabia, as spoken by Colonel Brighton

One

CROYDON DAYS

The town of Croydon, just south of London, has had some bad press down the decades. It may not be the most glamorous of places, probably being home to more accountants and insurance brokers than almost anywhere else in the Britain. Yet it’s also the birthplace of many a celebrity from the world of entertainment, among them actor–manager Sir Donald Wolfit, character actress Dame Margaret Rutherford, comedy star Arthur Lowe, stage legend Henry Irving, screen star Dennis Price, actress Sylvia Syms, music hall comedian Roy Hudd and actress Dame Peggy Ashcroft, after whom the local theatre is named.

Croydon’s most famous son, Oscar-winning film director David Lean, at first seemed destined to follow many of the town’s inhabitants into the dusty world of finance. Born at the family home, 38 Blenheim Crescent in South Croydon on Wednesday 25 March 1908, Lean’s father, Francis William Le Blount Lean, was himself not only a chartered accountant but a Quaker too, so the last thing anyone expected of the young Lean was that he would become a film director. Indeed, David and his brother Edward, younger by three years, were forbidden to go to the cinema as children by their mother, Helena Annie Lean, for fear of the corrupting influence it might have on them.

By the time Edward was on the scene, the family had moved some miles down the road to Merstham, which is where they were when the First World War broke out in 1914. However, it wasn’t the declaration of war, nor Francis Lean’s conscientious objections to being a part of it, a by-product of the family’s religion, that prompted their return to Croydon for the duration. It was the inability to get David admitted to the local school, a Church of England establishment, that caused the upset. Despite the return to Croydon for David’s schooling, he proved far from being an apt pupil. In fact, David was soon slipping behind his younger brother Edward as far as academic achievement was concerned, all of which proved frustrating not only to his parents, but to the increasingly introspective David.

By the time the war was over, while David was at prep school, The Limes, his parents not only resigned from their Quaker meeting house, but also split up; David’s father met another woman with whom he wished to spend his life. This came as a devastating blow to Helena and her two sons, especially given the stigma that separation carried in at the time. Francis Lean stayed a part of his children’s lives after this split, yet the fact that his new partner, with whom he eventually moved to Hove to live (unwed), had a young son of her own, must have made the sense of abandonment even greater to the Lean boys. It was at this darkest hour of his parents’ split that David saw his first film, director Maurice Elvey’s version of The Hound of the Baskervilles. The year was 1921 and Lean was already 13 years old.

Lean had developed a keen interest in still photography by this time, having been given a Kodak Box Brownie camera for his 11th birthday by an uncle. This interest in photography would later become a passion. At this stage, his experiences with cinema had all been second hand, via reports from friends, classmates and his parents’ char lady, a Mrs Egerton, who regaled the fascinated Lean with the antics of Charlie Chaplin. That first screening of The Hound of the Baskervilles must therefore have been quite a revelation, even if today much of Elvey’s prolific output (over 300 films) is critically reviled. To Lean, however, untutored as he was in the ways of even the simplest films, Elvey’s productions such as TheElusive Pimpernel and Dick Turpin’s Ride to York, accompanied by a live orchestra, must have been irresistible, especially given his burgeoning interest in adventure stories. Little did he then know but Lean would gain a foothold in the film industry as Elvey’s camera assistant some years later.

In the director’s chair. David Lean observes the action during the making of Madeleine in 1949.

During the next few years, Lean devoured everything the cinema had to offer, even taking trips up to London’s West End where he found himself enthralled by such films as The Big Parade and TheGold Rush. One director in particular greatly impressed him. This was the American Rex Ingram, a former actor and screenwriter who, in the early Twenties, took to making spectacular productions of such popular books as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, The Prisoner of Zenda and Mare Nostrum. The visual power of these movies apparently came as something as a revelation to Lean, for it was while watching them that he gradually came to realise that there were actually people behind the film cameras, shaping what he was watching on the big screen, just as he carefully composed the increasingly ambitious stills he took with his own Box Brownie.

In 1922, despite his lack of academic achievement, Lean was enrolled at Leighton Park Public School in Reading to continue his education. A progressive school in which the Quaker religion took a comparative backseat, it must have seemed like a breath of fresh air to Lean after his stifling experiences in education so far. Still, Lean’s academic standing continued on a very average path during his time at the school, although his outside interests – film, photography and a love of natural history – continued to develop.

When Lean left the school at the age of 18, there was still the question of what he would do for a career. Astonishingly, farming was the first occupation given serious consideration, although eventually David went to work as a junior at the accounting firm of Viney, Price and Goodyear in the City, which is where his father worked. Lean, with his poor grasp of maths, found the work tortuous and dull. Thus, in his spare time, his fascination with photography continued as a form of escape, even branching out into amateur home movies at one stage. Like many others of his generation, he also had a passion for radio, having a crystal set in his room at home.

Meanwhile, as if to push home the message that David was an underachiever, it was his younger brother Edward who, having also been sent to Leighton Park during David’s last couple of years there, was chosen by their father to be sent to Oxford to continue his education. It wasn’t long after this that David decided a career in accounting definitely wasn’t for him, but that perhaps a life in film-making was. The question was how to get that all-important first introduction? Surprisingly, the answer lay with his father.

Two

FIRST STEPS

Somewhat conveniently for David Lean, it transpired that his father Francis knew the accountants who dealt with the books for the Gaumont studios at Lime Grove. After much cajoling, David finally got his father to arrange an introduction for him at the studio, which resulted in his being interviewed by one of the studio’s executives, one Harold Boxall, who then passed him over to Gareth Gundrey, the studio’s production manager, who himself also occasionally wrote and directed films. David’s enthusiasm earned him a probationary period – unpaid – at the studio, working as a runner.

The year was 1927 and the Gaumont studios were expanding; there was plenty of work to keep technicians busy. Thus, in addition to making the tea and running errands, Lean also found himself working as a clapper boy on a film called The Quinneys being directed by Maurice Elvey. A silent production starring Alma Taylor and John Longdon, The Quinneys, which concerns the sale of some fake Chippendale chairs, was made in the established ‘silent’ manner, with Elvey shouting instructions to the actors as they worked through the various scenes, with a small orchestra always on hand in the background to provide suitable mood music. It is fascinating to think that there may be off-cuts of film somewhere showing the young Lean snapping his clapperboard in front of the camera before a take (a few frames do exist of Lean working on a film, as do several rare behind-the-scenes stills).

Following a difficult period, things were picking up in the British film industry, especially after the introduction of The Cinematograph Films Act in early 1928. This attempted to address America’s stranglehold on the film industry by guaranteeing that a quota of films shown in British cinemas were British in origin, thus securing employment for many actors and technicians. This had the less desired effect of heralding the ‘quota quickie’, in which studios churned out low-budget, low-interest support films simply to fulfil the quota. Nevertheless, some interesting talent emerged from the set-up, most notably director Michael Powell, who cut his teeth at the helm of a number of quota quickies in the early Thirties, treating the experience as equivalent to education in a modern day film school.

Gaumont may not have concentrated too heavily on quota film-making but it did give Lean the grounding he needed if he was going to make anything of himself in the film business. He also learned a little about film criticism at the time from one of the studio’s camera assistants, Henry Hasslacher who, using the pen name Oswell Blakeston, wrote for the highbrow magazine Close Up. Just as Herbert Pocket pretentiously re-Christened Pip as Handl in Dickens’ Great Expectations, Hasslacher decided to change David’s name to Douglas, which later caused some mild confusion when Lean decided to revert to his real name. This affectation aside, Hasslacher did show Lean that countries other than America and Britain successfully produced films, and although they seldom were shown outside their country of origin, except at film societies, they were often of a higher artistic value than those churned out by British directors such as Maurice Elvey.

In the late Twenties, Lean began to make a name for himself as an editor. By the time he came to make Doctor Zhivago he was a master of the craft. Here, he supervises the work of Norman Savage, who would go on to win an Oscar for his editing on Doctor Zhivago.

There was a lot for Lean to observe and take in during the following months, including the practicalities of cinematography, editing, film development, set construction and lighting. Such was his enthusiasm, however, that he absorbed everything, although his interest was most keenly taken by editing. When the opportunity arose, he jumped at the chance to watch Maurice Elvey cut TheQuinneys, proving to be a useful assistant to the director. He also observed Will Kellino direct SailorsDon’t Care, on which he assisted cinematographer Baron Ventimiglia, a role he continued on ThePhysician, which was produced by Maurice Elvey and directed by German George Jacoby. Lean also remained under the watchful eye of Elvey for the director’s next film, a thriller entitled Palais deDanse, on which Lean again assisted the director in various capacities.

By late 1928, Lean was a familiar face at Gaumont and, having gained confidence with Elvey, was also proving a valuable assistant to other directors, among them Edwin Greenwood, for whom Lean assisted with the camera on What Money Can’t Buy. He was also persuaded to appear in front of the lens, too, in a brief walk-on role, sharing a few frames with the film’s star, Madeleine Carroll. Unfortunately, a blunder by Lean in the dark room lost some valuable footage which subsequently had to be re-shot. As a consequence he was taken off What Money Can’t Buy and was demoted to wardrobe ‘mistress’ for his next assignment. A lavish re-enactment of the Charge of the Light Brigade, it went by the title Balaclava and was directed by Maurice Elvey. A major production of its day, it proved to be a big success for the studio. Nevertheless, Lean hated his time on the film, on which his duties involved handing out, retrieving and maintaining the hundreds of British and Russian uniforms needed for the production. It’s hard to imagine Lean sitting, needle and thread in hand, sewing on a button or doing a quick bit of repair work!

By the time Balaclava was released, technology had marched on apace. In America sound was now all the rage thanks to the pioneering success of Don Juan and The Jazz Singer, both of which had been made by Warner Brothers using the Vitaphone process. Released in 1926 and 1927, respectively, these two films, along with a number of Vitaphone novelty shorts, helped to revolutionise the industry. Britain quickly jumped on the bandwagon, with Alfred Hitchcock re-shooting much of his 1929 film Blackmail, originally made as a silent, to take advantage of the new medium. Made for British International Pictures (BIP), the film proved an instant hit. Gaumont wasn’t far behind, reissuing Balaclava with a music and effects soundtrack. The studio also put into production a futuristic fantasy entitled High Treason. Directed by Maurice Elvey and based on a play by Noel Pemberton-Billing, the film, set in 1950, is a pacifist tract in which women unite to prevent the outbreak of a second world war. Seemingly forgiven for his dark room gaffe on What Money Can’t Buy, Lean was back as Elvey’s assistant on the film, which was also released as a silent, owing to the slow changeover to sound in the cinemas of Britain’s smaller towns and villages.

The coming of sound proved to be the making of Lean, for after assisting on High Treason, he went on to help director Sewell Collins in the cutting room with a musical short called The NightPorter. Unfortunately, Collins couldn’t master the craft of sound cutting. Lean, however, learning from newsreel editor John Seabourne, quickly took in the basic rudiments of synchronisation and proved valuable to Collins in the editing of the picture. This did much for Lean’s standing at Gaumont, so much so that following the departure of John Seabourne to another company – plus a costly editorial blunder by his replacement, Roy Drew – Lean was given the job of editing the Gaumont Sound News. Lean had come a long way in his few years at Gaumont, and all by the age of 21.

Three

CUTTING EDGE

Lean quickly proved his worth in the Gaumont News cutting rooms, handling with speed and efficiency breaking stories such as the crash of the R101 airship in France. News of the crash came on the morning of Sunday 5 October 1930; by that evening Lean had cobbled together a report on the disaster which was subsequently played in cinemas, complete with a commentary by Lean himself.

Closer to home, developments were also taking place in Lean’s personal life. An affair with his first cousin Isabel resulted in her getting pregnant during a trip to Paris. Isabel and David saw no option but to get married, which they did on Saturday 28 June 1930. The birth of their son, Peter David Tangye Lean, followed on Thursday 2 October the same year. With his busy workload, Lean was barely around at the home that he shared with Isabel and the baby in London’s Holland Park, which was perhaps just as well, for although proud to be the father of a healthy son, Lean wasn’t the ideal candidate for the job of parenting. Rather than family and home, his life centred around work. Changing nappies and digging over the garden were just not his forte. Lean thrived in the cutting rooms, and with EVH Emmett taking over from Lean as commentator, Gaumont Sound News quickly established itself as a staple programme with cinema audiences.

In 1931, Lean was offered a job at British Movietone News. His duties would be more or less the same as they had been at Gaumont, but the pay would be better. Given his domestic situation, Lean quickly agreed to take the job. It was also in that year that Lean edited his first feature film. A light society comedy starring Nora Swinburne and Godfrey Tearle entitled These Charming People, it was directed by Swiss-born Louis Mercanton. He was best known for co-directing (with Henri Desfontaines) the highly successful and influential 1912 film Queen Elizabeth (aka Les Amours de laReine Elisabeth), starring the legendary stage tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt. Unfortunately, Lean was carried away by his enthusiasm and, having cut just one reel of the film, was demoted to assistant editor. There was a lot of difference between editing a newsreel and a feature, and Lean still had much to learn. The demotion must have hurt his pride considerably but it was back to the newsreels. These Charming People is all but forgotten today, although it has one interesting footnote: Lean’s future wife, Ann Todd, had a small role in it.

Undeterred by his setback, Lean was determined to master the art of feature cutting. Consequently, when not tied up with newsreels, he became a familiar face in the studio’s other editing suites, often assisting the cutters with their work, simply to gain experience. His efforts eventually paid off, for he was asked to go to Paris to edit a Foreign Legion picture entitled Insult, which had been directed by an American Harry Lachman. Set in North Africa, it stars the young John Gielgud, Elizabeth Allan and Sam Livesey. Like These Charming People, it is forgotten today. Nevertheless, it was an important stepping stone for Lean, for it provided him with his first official feature credit. However, his lengthy absence and increased workload put an unbearable strain on his marriage, which Lean decided to end in mid-1932, leaving Isabel and his young son to fend for themselves.

Lean’s next feature assignment was Money for Speed for the British and Dominion (B&D) studio, starring John Loder, Cyril McLaglen and a young Ida Lupino. A low-budget quota quickie, it marked the directorial debut of the German-born Bernard Vorhaus, who had been working in America as a writer before this assignment. Although a routine production, Vorhaus and Lean got on well together, so much so that after cutting Matinee Idol for director George King, Lean went on to edit Vorhaus’s next film, the equally low-budget Ghost Camera, starring Henry Kendall. The plot concerns Kendall as a chemist who, while on holiday, inadvertently picks up someone else’s camera and decides to develop the film inside to see if he can trace the owner through it: his investigations uncover foul play. Despite this promising scenario, the film, based on a novel by Jefferson Farjeon, is scuppered by its low budget, Vorhaus’s stilted handling and some fairly stiff performances from Kendall, Ida Lupino, George Merritt and John Mills; no amount of clever cutting on Lean’s part could salvage it.

Nevertheless, Lean was gaining experience as an editor by leaps and bounds, and he learned some useful tips from B&D’s editor-in-chief, an American named Merrill White, who had cut innovative Hollywood films such as The Love Parade for Ernst Lubitsch and Love Me Tonight for Rouben Mamoulian, each of which are notable for their stylish and pioneering use of sound and music. Consequently, despite having just edited newsreels and a handful of unimpressive B movies, Lean’s reputation was growing, even to the point that other editors at both his own and other studios would ask for his help and advice when they ran into problems. In 1933, in addition to the three features he’d already cut (Money for Speed, Matinee Idol and The Ghost Camera), his newsreel work and his unaccredited work as a trouble-shooter, he cut a further two features. The first of these, Tiger Bay, stars Henry Victor and Anna May Wong and was directed by designer–director J Elder Wills for Ealing. The second, Song of the Plough, stars Rosalinde Fuller and Stewart Rome, and was directed for B&D by John Baxter, later known for such social dramas as Love on the Dole.

The heavy workload continued into 1934 with Dangerous Ground, a thriller starring Joyce Kennedy and Malcolm Keen, directed by Norman Walker for B&D. This was followed by the more interesting Secret of the Loch. Directed by Milton Rosmer for Ealing, it centres round a diver’s belief that he has encountered the fabled monster in Loch Ness’ murky depths. Starring Seymour Hicks, Nancy O’Neill, Gibson Gowland and Rosamund John, the film exploited a resurgence in interest in the Loch Ness myth (complete with a magnified lizard), and proved mildly popular, despite being a pretty shoddy piece of work.

Assisting Merrill White, Lean next tackled the Anna Neagle vehicle Nell Gwyn, which had been directed by Herbert Wilcox and photographed by Freddie Young, then B&D’s cinematographerin-chief. Nell Gwyn marked the first of several close encounters between the future director and the established cinematographer, although their partnership wouldn’t become a reality for another 25 years.

Studio portrait of producer/director Herbert Wilcox, for whom Lean edited several films in the early to mid-Thirties. Among them was Nell Gwyn in 1933, photographed by Freddie Young, who would photograph Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia over 25 years later.

In the meantime, Lean kept slogging away in the cutting rooms with Merrill White, his next job being an adaptation of George Barr McCutcheon’s oft-filmed comedy Brewster’s Millions, which had been tailored for debonair song and dance man Jack Buchanan. A lively production, it was the first British film from the American director Thornton Freeland, then best known for the Eddie Cantor musical Whoopee, and Fred Astair and Ginger Rogers’ breakthrough hit Flying Down to Rio. Again, among the Brewster’s Millions’ credits could be found one of Lean’s future collaborators. This time it was Anthony Havelock-Allan, who would go on to produce many of Lean’s films, although at this stage Havelock-Allan was a casting director.

In addition to his official work for B&D, 1934 also saw Lean work on Java Head with editor and future director Thorold Dickinson over at ATP for producer Basil Dean. Like Brewster’s Millions, JavaHead, a period romantic drama about a Bristol shipbuilder, marked the British debut of another American, J Walter Ruben who, before his work here, had directed a number of unambitious productions in Hollywood at both RKO and MGM, among them Where Sinners Meet, Public HeroNumber One and Riff Raff, the latter of which, a con-man comedy, had at least been enlivened by the performances of Jean Harlow and Spencer Tracy. Ruben’s work on Java Head was equally unambitious, and despite an interesting cast that included Anna May Wong, John Loder, Edmund Gwenn, Elizabeth Allan and Ralph Richardson (later to appear in Lean’s The Sound Barrier and DoctorZhivago), the film needed all of Dickinson’s and Lean’s talents to bring it to life.

The year of 1935 brought a better prospect in the form of Turn of the Tide, a would-be prestige production about two fishing families who feud, like Montague and Capulet, until their arguments are quelled by a romance and marriage. Produced by John Corfield for British National, the film remains important for the fact that it was the first production financed by the Methodist flour magnate J Arthur Rank, who entered the industry in a bid to promote religion, but ended up heading the largest and perhaps most influential and prolific production company in British film history. He was responsible for such subsidiary outfits as The Archers, Two Cities and Cineguid, the latter was co-founded by Lean, Ronald Neame and Anthony Havelock-Allan, through which they would make This Happy Breed, Blithe Spirit and Oliver Twist.

Directed by Norman Walker (Tommy Atkins, The Middle Watch), Turn of the Tide, based on ThreeFevers by Leo Walmsley and starring Geraldine Fitzgerald (making her film debut), John Garrick, Niall MacGinnis, Wilfred Lawson and Moore Marriott, was photographed by the German-born Franz Planer (who’d go on to photograph Hollywood spectaculars such as 20,000 Leagues Under theSea, The Pride and the Passion and The Nun’s Story). As with Java Head, Lean worked unaccredited on the film, which went on to surprise everybody by earning some very respectable reviews, although the American trade paper Variety pointed out that the 80-minute production would have benefited from being, ‘Cut to an hour,’ to, ‘make an acceptable second feature.’

It was back to B&D for the even more prestigious Escape Me Never starring German refugee Elisabeth Bergner as Gemma Jones, a waif who marries a composer to provide a name for her illegitimate child, only to discover that the musician loves another. Despite the scenario (based on the play by Margaret Kennedy in which Bergner had appeared in both London and New York), the film was lavishly produced by Herbert Wilcox (including location work in Venice and The Dolomites), with director Paul Czinner (another refugee from Hitler’s Germany and also Bergner’s lover and future husband) bringing out the best qualities in the star, who went on to earn an Oscar nomination for her performance. Although Bergner would ultimately lose the award to Bette Davis for Dangerous, the nomination at least helped to raise the film’s profile in America, where Variety commented that, ‘Its able presentation commands attention.’

For Lean to have been chosen to edit the film for the highly respected Czinner (Der TraumendeMund, Catherine the Great, both starring Bergner) was a major coup, and he learned much from observing the director at work filming the interiors at the B&D studios. Lean would go on to edit a further two films for Czinner. However, before that came another move (or perhaps Lean was ‘poached’ after the success of Escape Me Never), this time to Elstree, where his first assignment was Ball at the Savoy for producer and occasional director John Stafford. Little seen today, the film, a romance starring Conrad Nagel, Marta Labarr, Lu-Anne Meredith and Esther Kiss, was directed by Victor Hanbury (Admirals All, The Crouching Beast).

Ball at the Savoy may have been something of a non-event, but Lean’s private life was becoming increasingly busy with a string of romances and affairs, among them Ball at the Savoy starlet Lu-Anne Meredith, all of which culminated in Lean’s bid for true freedom by asking Isabel for a divorce, which she finally agreed to in 1935.

Back at work with Paul Czinner, Lean edited an adaptation of As You Like It, for which he earned an incredible £60 a week, an industry record at the time for an editor. A major production, As YouLike It is notable for the talent involved, which includes the Russian-born Hollywood producer Joseph M Schenck, who helped to finance the film through Twentieth Century Fox, of which he was the founder. The screenplay was by Peter Pan author JM Barrie and Robert Cullen, the cinematography by American Harold Rosson (already a veteran from Tarzan of the Apes and TheScarlet Pimpernel, with The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain to come), while the music was by William Walton, who’d provided the score for Czinner’s Escape Me Never. Elisabeth Bergner heads the cast as Rosalind, and she is supported by Laurence Olivier (Orlando), Leon Quartermaine (Jacques), Sophie Stewart and Felix Aylmer, while further down the list can be found Peter Bull and John Laurie.

Despite the best efforts of all concerned (Lean even did a couple of days directing on the picture when Bergner fell ill and Czinner went to her bedside), the film was over-produced, while Czinner’s restrained directorial approach resulted in several slow passages, prompting Graham Greene to observe in The Spectator, ‘Czinner has been too respectful towards stage tradition. He seems to have concluded that all the cinema can offer is more space: more elaborate palace sets and a real wood with room for real animals. How the ubiquitous livestock weary us before the end.’ Like many Shakespeare films of the Thirties, such as George Cukor’s Romeo and Juliet (with its 43-year-old Romeo and its 36-year old Juliet) and Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, As YouLike It is an over-decorated affair. Graham Greene continued, ‘How disastrously the genuine English woodland is spoilt by too much fancy, for when did English trees, in what apparently is late autumn, bear clusters of white flowers?’

A stirring performance. Elisabeth Bergner in the 1937 remake of Dreaming Lips. The film was directed by her husband, Paul Czinner, and edited by David Lean.

Perhaps all (Czinner, Bergner, Lean, William Walton) were more comfortable with their next production, Dreaming Lips, a less consciously arty and more typical star vehicle concerning the wife of an invalid musician who commits suicide after having an affair (indeed, Bergner and Czinner had already successfully tackled the subject in Germany in Der Traumende Mund in 1932). It went down a storm with female audiences (‘How the handkerchiefs flutter at the close,’ wrote Graham Greene in The Spectator). Based on the play Melo by Henry Bernstein, the film was again made by top class talent, among them writer Margaret Kennedy (the author of The Constant Nymph and Escape MeNever), who penned the screenplay with Lady Cynthia Asquith and the German-born Carl Meyer. The latter was already a Czinner veteran having co-written the screenplays for Ariane and DerTraumende Mund, although he was perhaps best known for The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, The Last Laugh and Sunrise. Although Meyer would live until 1944, Dreaming Lips would be his last screenplay.

Also involved behind the cameras was the noted American cinematographer Lee Garmes, hailed for his work on Zoo in Budapest, Scarface and Shanghai Express, the latter earning him an Oscar for his lighting of Marlene Dietrich, which was no doubt why he was hired to photograph Bergner (although Dreaming Lips would be his only British film). The art department was headed by the Russian-born Andrei Andreiev, assisted by Tom Morahan, while the film was financed and produced by a Czechoslovakian Max Schach. The international flavour was also carried over into the cast, with Bergner supported by Mexican Romney Brent and Canadian Raymond Massey, while Joyce Bland, Sydney Fairbrother, Felix Aylmer and Donald Calthrop batted for England.

A glossy production, the film earned some strong notices: Variety commented, ‘One of the finest productions ever made in England. [Had it been] made in Hollywood, the story would be whitewashed and much of its strength weakened.’ Unfortunately, the film wasn’t the commercial hit everyone hoped it would be. However, Lean found consolation in another affair he’d started, although this time the relationship would prove longer lasting. The name of the girl, an up-and-coming actress, was Kay Walsh who, having gained experience as a dancer in revue in London’s West End, had made her film debut in 1934 in Get Your Man, which she had followed with appearances in How’s Chances?, The Luck of the Irish and The Secret of Stamboul. Although none of these films left a lasting mark, Walsh would go on to become one of Britain’s most-liked female leads – she also ended up becoming the second Mrs David Lean.

Four

LEAN TIMES

After the commercial disappointment of Dreaming Lips, Lean was unemployed. Worse still, he had been less than prudent with his money. He had to move from the luxurious apartment he’d been living in at Mount Royal – a haven for the film industry close to Marble Arch – and into the lodgings at which Kay Walsh was living (a bold step given that the couple weren’t yet married and cohabiting was taboo at the time).

At least Walsh was working, her appearance in the play The Melody That Got Lost having earned her a contract with Ealing Studios, where her first film was the George Formby vehicle Keep Fit. Produced by Basil Dean and directed with verve by Anthony Kimmins, it was an immediate hit and did much to help establish Walsh with audiences (certainly more so than the programmers and potboilers in which she’d previously appeared). Also among the burgeoning talent involved in the film’s making was cinematographer Ronald Neame and art director Wilfred Shingleton, both of whom would later make substantial contributions to Lean’s films.

The long period of unemployment for Lean came to an end when he was approached to edit TheLast Adventurers in 1937. By no means a prestige production in the Czinner manner, the film was a low-budget drama involving the adventures, romantic and otherwise, of the crew of a fishing trawler. But the rent needed paying and the film achieved its modest goals adequately enough. Produced by Henry Fraser Passmore, it marked the directorial debut of respected cinematographer Roy Kellino, while the cast included such familiar faces as Niall MacGinnis, Peter Gawthorne, Linden Travers, Katie Johnson (remembered for her later performance as the kindly old landlady in The Ladykillers) and, in a supporting role, Kay Walsh, whose fee no doubt also came in handy for the household bills.

Lean must have been a little more cautious with the money he earned from The Last Adventurers because he didn’t edit a feature again for almost a year. Work was also a long time coming for Walsh too, who was cast to appear opposite George Formby again, this time in I See Ice. Like Keep Fit, the film was directed by Anthony Kimmins, with Ronald Neame and Wilfred Shingleton involved again as cinematographer and art director, respectively. Soon after, Walsh also secured a supporting role in another comedy, a minor effort entitled Meet Mr Penny, which centres round a clerk’s attempts to prevent a property tycoon from building on some local allotments. Directed in a workmanlike fashion by the prolific David MacDonald (Double Alibi, The Lost Curtain), the film features radio star Richard Goolden (known to millions as Old Ebenezer), Vic Oliver, Hermione Gingold, Fabia Drake and Wilfred-Hyde White. Despite these familiar faces, it was quickly forgotten.

When things were just about as bad as they could get financially, Lean was given the opportunity to edit his most prestigious film yet – an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 masterpiece Pygmalion. Made in 1938, it is rightly regarded as one of the great British films of the Thirties and went on to become the country’s biggest money maker in 1939, earning kudos for all involved.

A rare still of Pygmalion’s producer, the flamboyant Hungarian Gabriel Pascal, pictured giving instructions to Stanley Holloway and Leo Genn during the making of Caesar and Cleopatra.

Born in Ireland in 1856, George Bernard Shaw was one of the leading playwrights of his generation (Saint Joan, The Millionairess, Major Barbara, Man and Superman). Yet perhaps because his life was almost halfway over before the invention of cinema, he was always wary of the medium, and given the resultant mediocrity of the few plays he’d allowed to be filmed before Pygmalion, one can understand why. Among the disappointments had been a half-hour version of How He Lied toHer Husband starring Edmund Gwenn (notable chiefly for an early screenplay credit by Frank Launder) and a lacklustre adaptation of Arms and the Man with Barry Jones (as Bluntschli), Anne Grey and Angela Baddeley (later known for playing Mrs Bridges in television’s Upstairs Downstairs). Both of these films were directed (in 1930 and 1932, respectively) with Shaw’s blessing, by Cecil Lewis for BIP. There had also been a German version of Pygmalion in 1935, plus an attempt by Paul Czinner to film Saint Joan with Elisabeth Bergner in 1936. Unfortunately, this proposed production (which would invariably have been edited by Lean) was scuppered by Shaw when Czinner expressed fears about a Catholic boycott.

Enter a silver-tongued Hungarian producer named Gabriel Pascal who, although practically penniless, was determined to produce a series of films in Britain based on Shaw’s works, the rights to which he miraculously managed to secure during a meeting with the playwright, who was suitably amused and impressed by Pascal’s bravura and sheer effrontery, if not by his bank balance. Before Pygmalion, Pascal had made films in Italy (Populi Morituri, as both actor and co-director) and Germany (Friedrike, Unheimliche Geschichten, which he produced), as well as Britain (Reasonable Doubt and Cafe Mascot, which he produced, the latter based on a work by Cecil Lewis). Yet despite his contacts in the business, it took Pascal some considerable time to set up the financing for Pygmalion. Once secured, the producer put to work Cecil Lewis and WP Lipscomb on adapting the play for the screen, over which Shaw had complete control.

The story revolves around the phonetics teacher, Professor Henry Higgins, who takes up a bet from his friend Colonel Pickering that he can’t turn a Cockney flower girl – Eliza Dolittle – into a lady and pass her off in high society. This the Professor successfully does but not without learning a little about humanity along the way. Lewis and Lipscomb’s work on the screenplay primarily involved streamlining the play without drastically altering its structure or dialogue. Inevitably, certain expositional scenes, necessary in the theatre but less vital on screen, fell by the wayside in a bid to keep the narrative flowing, while the freedom of film also allowed the creation of several entirely new scenes and exchanges of dialogue, the most important of which was Eliza’s triumph at the ball, alluded to but not actually part of the original text. Shaw wrote this lengthy new sequence himself, which involved the creation of an entirely new character, the Hungarian Aristid Karpathy, a former pupil of Higgins’, now himself a noted phonetician, whose ear for dialect could well expose Eliza for the fraud she is.

By this time Anthony ‘Puffin’ Asquith, the son of the former Liberal Prime Minister Lord Herbert Asquith, was on board as director. At the time Asquith may have seemed a curious choice, for although he would later distinguish himself with such classics as The Way to the Stars and TheImportance of Being Earnest, and had made a splash with his debut feature Shooting Stars back in 1928, his recent career had included some notable failures, among them the Gallipoli-set drama TellEngland (‘Not likely to bring in any money’ commented Variety) and Moscow Nights (the direction of which Graham Greene described as ‘puerile’ in The Spectator).

Perhaps because of this, working alongside Asquith as director, as well as playing Professor Higgins, was the popular romantic lead Leslie Howard, known for successes such as Of HumanBondage and The Scarlet Pimpernel (although apparently Shaw’s preferred choice for Higgins was Charles Laughton). Playing Eliza was Wendy Hiller, whom the film would ‘introduce’ and whom Shaw himself had apparently ‘discovered’ in a production of his play Saint Joan (despite the fact that Hiller had already starred in a film in 1937 entitled Lancashire Luck, a comedy about the effect a pools win has on a poor family). The film also contains the first screen appearance (brief and unaccredited) of future star Anthony Quayle as an Italian wigmaker.

The pedigree of those involved behind the cameras was no less impressive, among them cinematographer Harry Stradling (who would go on to win an Oscar for photographing My FairLady, the musical version of Pygmalion, in 1964), French composer Arthur Honegger (Napoleon, LesMiserables, Crime et Chatiment