Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Third Editions

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

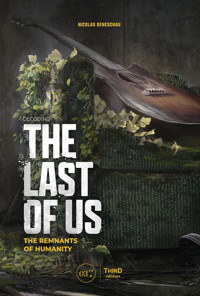

How far would I go for love? This profound question drives the visceral storytelling of The Last of Us. Love is the central theme for people like us. We find it in literature, cinema, TV series, the most extravagant reality shows and, in this case, video games. After disrupting the adventure game formula with the acclaimed Uncharted series, Naughty Dog changed its recipe in 2013 with The Last of Us, embracing the post-apocalyptic genre. Seven years later, The Last of Us Part II offered a more radical and divisive experience, but still focused on people, their motivations and their flaws. With the book "Decoding The Last of Us: The Remnants of Humanity", author

Nicolas Deneschau invites us to grasp all the complexity behind the design of these titles, as well as the meticulousness of their authors and development teams. He analyses the many ways The Last of Us can be read and considers the important role the diptych played in the transformation of the blockbuster video game.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 656

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Couverture

Page de titre

Never woulda run through the blinding rain

Without one dollar to my name

If it hadn’t been

If it hadn’t been for love

Never woulda seen the trouble that I’m in

If it hadn’t been for love

Woulda been gone like a wayward wind

If it hadn’t been for love

Nobody knows it better than me

I wouldn’t be wishing I was free

If it hadn’t been

If it hadn’t been for love

Four cold walls against my will

At least I know she’s lying still

Four cold walls without parole

Lord have mercy on my soul

Never woulda gone to that side of town

If it hadn’t been for love

Never woulda took a mind to track her down

If it hadn’t been for love

Never woulda loaded up a 44

Put myself behind a jailhouse door

If it hadn’t been

If it hadn’t been for love

Four cold walls against my will

At least I know she’s lying still

Four cold walls without parole

Lord have mercy on my soul

If It Hadn’t Been for Love

The SteelDrivers (The SteelDrivers, 2008

PREFACE

“Anything you love too violently always ends up killing you.”

Guy de Maupassant

How far would I go for love?

Love is the key theme in our lives as human beings. It’s the number-one subject among all works of literature, film, television series, reality shows–no matter how outrageous–and of course, video games, which prove to be just as valid a form of artistic expression as any other. And on that point, I’d like to stress how the relatively new medium has gradually risen to greater prominence while taking on the theme of love. Bit by bit, video games have dared to explore relationships between individuals, entering the “private sphere” that has assumed a prominent place in contemporary societies. Video games have demonstrated the importance of recognition, of individual fulfillment, of respect for others, and for gender diversity through romantic relationships. In the world of video games, love is represented in many different forms. It can be as simplistic and archetypal as saving a damsel in distress in games like Super Mario Bros. or The Legend of Zelda. It can also be as mechanical and systematic as an Excel spreadsheet in games like The Sims and Mass Effect. Sometimes, however, it is handled with greater care and finesse, as in Catherine, in which a young man must choose between two women to whom he finds himself attracted. Love can even take on a tragic dimension, as with the ill-fated love stories of Shadow of the Colossus, Deadly Premonition, or Final Fantasy VII.

With all these varied forms, love has become a new paradigm in video games. The fascinating thing about studying it is that it allows you to observe the sociology of its context and time. Dying for the love of one’s cause in Assassin’s Creed, for love of one’s country in Call of Duty, or for the love of the kingdom in Mount & Blade–love has a lot to teach us about what it means for something to be sacred. What are we willing to die for if not for love? But in today’s world, in the West, who would be willing to die for God, for their country, or for a revolution? On the other hand, it almost goes without saying that the only people we’d be willing to die or risk our lives for are those we love. A child, a parent, a loved one, the person we can’t live without, the center of our lives so narrowly focused on friends and family in our individualistic, hedonistic modern societies. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t say this out of disenchantment; we should rejoice about these changes that have given a new image of what it means to be sacred.

Sacred now bears a human face. It’s this wisdom of love, of humanity, that makes the great dramatic patriotic or political stakes of games like Assassin’s Creed or Call of Duty seem so trifling, as examining the misfortune of a single man ultimately makes us more inclined to understand the misfortunes of all others. So, in order to more effectively examine love, hate, and death, ideally, we would need to obliterate anything that might interfere with the context. There would be no more place for country, for kingdom, or for God. The relationships would have to be so intense and so primal that they would be like magnifying glasses for the audience, allowing them to better observe the characters. Death and the risk of losing a loved one would have to be so imminent and tangible that the only possible form of expression would be the truest and purest love. There would have to be an apocalyptic event ravaging the world, leaving just a handful of people willing to do whatever it takes to save their loved ones.

“Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real.”

Cormac McCarthy

Post-apocalyptic fiction is a form of puppet theater

The term “apocalypse” has never been used more than in our contemporary media, artistic, and cultural vocabulary. It’s as if the old myth reveals our mystical fascination with the end of time and normalizes our fatalistic feelings about the relentless degradation of our environment and society. The sudden profusion of a certain kind of apocalyptic fiction–and, by extension, stories of the “after times,” i.e., post-apocalyptic fiction–whether in film, literature, television, or video games, is no random matter of happenstance. After all, there’s nothing new about it, given that the term, which comes from the Greek apokálypsis (literally meaning “divine revelation”), became increasingly common between the 2nd and 1st centuries before the common era as a literary subgenre dealing mainly, in symbolic form, with the fate of the world and God’s people. However, in the Industrial Age, the term passed a point of no return on August 6, 1945, when a nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, drastically transforming the meaning of the word “apocalypse.” From there, Earth entered a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. Humanity began to see things through a new lens. While the apocalypse had once been God’s weapon for controlling his people, the province of religious belief, it transformed into a tangible reality. In the 20th century, humans became the principal threat of destruction and annihilation of all life on Earth. And the evidence of our entry into the Anthropocene epoch continues to be increasingly obvious. Our planet faces numerous environmental dangers, increasingly deadly wars, massive downward spirals into sectarianism, and supersized pandemics driven by limitless globalization. The apocalypse no longer has anything to do with God; it’s all about humanity now.

Thus, since World War II, each type of threat–nuclear, toxic, environmental, or chemical–has given rise to its own vein of apocalyptic imagery in popular culture. The post-apocalyptic subgenre has become a contemporary form of tragedy. After the world ends, what comes next? Despair? Hope? In any case, the post-apocalyptic tale is a sort of entreaty to the audience. While it may be too late to avoid the apocalypse, perhaps you can prevent history from repeating itself. A fascinating context for a story. If there is no more hope for the future, can we conceive of a new present? Post-apocalyptic fiction thus frees itself from the constraints of our own age and sets its action in humanity’s dying days. Ultimately, isn’t it a remarkable way to arm ourselves in order to prevent the end of time?

In The Last of Us from the studio Naughty Dog, a game that unambiguously embraces the post-apocalyptic subgenre of fiction, a mysterious global pandemic decimates our modern society within a matter of days. The infection–caused by a mutated species of Cordyceps, a parasitic fungus that destroys its human host, much like how the same genus of fungi kills insects in the real world–really proves to be just a narrative device that moves the focus from the dystopia of the after times to a character study. After all, humanity’s problem is humans, not God. Naughty Dog is less concerned with its universe, belonging to a highly codified subgenre, than it is with its characters. With the end of the world being of humanity’s own doing, the story’s authors choose to focus their attention on those very same humans. The plot of The Last of Us thus proves to be totally timeless. The context is just a pretext for heightening the personalities and advancing the action. Naughty Dog amused itself by roughing up its marionettes and then cutting their strings one by one. The Last of Us has all the trappings of modern tragedy, but stubbornly rejects the simplistic dichotomy of good versus evil. The game also has the trappings of both Greek and humanistic tragedies. Shaped by a catastrophe, the game’s strong, captivating characters must live with the consequences for the rest of their lives, and the time loop repeats endlessly: the loss of a loved one, vengeance left unsatisfied, and on it goes.

It may seem unnecessary to specify this, but it will only add a few extra characters to be printed: this book, which humbly invites the reader to re-examine the two volumes that make up this saga, to understand the process of the games’ creation, and to explore the fascinating themes that they offer, is best enjoyed if you have already played The Last of Us and The Last of Us Part II. From the very first pages, the plot of the two games will be spoiled and then, later, dissected. Consider yourself warned.

Evoking emotion

Sometimes, an experience is so intense that it haunts you for years. There are surprising moments that are so memorable that no matter what you do, you can’t just forget about it. You try to direct your thoughts elsewhere, to do things differently, but to no avail. The experience continues to take up space in your mind. It may be an ex-boyfriend or-girlfriend, something that happened in your childhood, a trauma, or even a work of art, whatever the case may be. The experience plants itself in your subconscious and refuses to leave. You try to fight it off, but it still remains. In fact, as you read these lines, you probably have such an experience in mind. Something that has stayed with you for years–perhaps a thought that you’ve shared with no one or that you’ve only spoken of on very rare occasions. Instead, you keep that secret deep within yourself, buried under an array of emotions. These experiences that affect us so profoundly are fascinating in more than one way, given how they define us as people. They shape our personalities and our ways of being. You may even find yourself wanting to conjure up certain experiences using artifacts, like a song that reminds you of a summer night, a book connected with a particular moment in your life, a photo, a movie, or even a video game.

Most of the time, when a player sits down and starts up a video game, they’re just looking to have some fun. In concrete terms, playing a video game boils down to a series of repetitive actions that may eventually lead your brain to release a few hits of dopamine in the best-case scenario, giving you satisfaction and a feeling of accomplishment, things that the player probably seeks without always realizing it. It is more unusual, and a much more recent phenomenon, for the player to seek a novel emotional experience. At the end of the aughts, people in the video game world talked about emotion very delicately. Viewed with wariness, or even a certain kind of disapproval, the term “emotion” was long treated with curiosity in the tightknit video game community. On the one hand, the expression has been debased by certain condescending developers when talking about the medium and, on the other hand, a community had formed to act as the reactionary guardian of the temple, ready to launch a veritable crusade against anyone who would dare to try to change things. Burnt by experiences that most likely erred too far towards the cinematic side, like Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain or the works of Telltale Games, players reproached creators for taking up the paternalistic yoke of cinematic storytelling. As a matter of fact, in 2009, director Guillermo del Toro drove that point home when he predicted that film would become an offshoot of video games. What people didn’t understand at the time is that video games didn’t need to mimic film, but rather needed to forge their own path forward to tell stories and stir new emotions in players. It’s precisely when video games free themselves from their overbearing ancestor that they succeed in offering their most memorable experiences. Fumito Ueda’s ICO (2001) and Shadow of the Colossus (2005), Jenova Chen’s Flower (2009) and Journey (2012), or Yoko Taro’s NieR (2010) are all games that transcend the traditional codes of film to invent their own storytelling tools. The player isn’t the invisible witness to the action; they are the actor. Still, in these games, interaction is no longer limited to frenetically repeating an action until it evokes pleasure; it is entirely dedicated to stirring emotions. Without the interaction, the emotional investment of the player is not possible. Fear, joy, sadness, fulfillment, stress: the more the video game medium progresses, the more varied the emotions become and the more subtle their delivery.

In spite of the very conservative and disapproving attitude towards attempts at doing things differently with the medium–as if video games should never have evolved since Space Invaders, or as if film could be boiled down to a medium meant to make viewers laugh with nothing more than a pie to the face–it’s actually an incredible tool, a sort of Trojan horse, for conveying emotions. When you play a game, when you submit yourself to an exotic diegesis1 that comes with its own set of rules, your psychological and rational defenses as a player come way down; as such, you become more vulnerable to the emotional charms crafted by the creators. Very early in video game history, developers ventured down the path of evoking the most primal emotions: fear in the survival horror subgenre, laughter in point & click games, etc. Year after year, developers honed the subtle balance between storytelling and gameplay, seeking the Holy Grail: having the gameplay become the logical result of the storytelling, and vice versa. Among the developers who have taken that risk, some have made it their signature: Quantic Dream, Telltale, Don’t Nod, CD Projekt, Rockstar, and… Naughty Dog.

The California-based studio has been making games for a long time, but hasn’t always focused on the medium’s storytelling potential. The Uncharted saga, which started with Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune in November 2007, certainly put the emphasis on its characters and the quality of its dialogue, but it was also rightfully criticized by reviewers and audiences, particularly for its barely adapted cinematic side and, above all, for the very real dissonance between what the story tells us and the actions that the player must carry out through the characters. It’s just not “realistic.” I don’t mean realistic in the sense of scientifically credible; I mean it in the context of the pact between the player and the game’s universe. The game doesn’t feel “grounded,” by which I mean consistent, realistic, and authentic. There’s no problem with a character having superpowers if that’s consistent with the game’s story, but it’s hard to accept the actions and attitudes of another character if they run contrary to their characterization. For Naughty Dog, which was quick to take this critique very seriously, the turning point was in one game in particular. A title that would literally redefine a whole segment of narrative game design. A title that came out of nowhere, not belonging to any established franchise. A game that would appear on store shelves on June 14, 2013, at the very end of the PlayStation 3’s life span, in spite of the fact that the market was already decidedly orienting itself towards the next generation of consoles.

The Last of Us was not created to be a revolutionary title. Moreover, none of Naughty Dog’s games have ever adopted such an ambition. Naughty Dog is a goldsmith, an artisan who takes a raw material and creates something sublime. During development, some of the studio’s teams even expected the title to be a flop. That opinion seems ridiculous from where we stand years later, given the game’s impressive legacy. However, it’s perfectly understandable when we put things in context. At the time, multiplayer games were king; the video game press and social media were predicting the end of the solo game. The universe created by Neil Druckmann was nihilistic, sad, and demoralizing, a far cry from the exotic and colorful backgrounds of the company’s previous hits. Whereas Uncharted was the champion of humor and action free of complexes, The Last of Us presented itself as tragic, slow-moving, and resolutely human. Naughty Dog took a risk by betting on such a paradigm shift, a risk that nonetheless paid off since, today, the game is considered one of the greatest milestones of video game storytelling, or even of video games, full stop. A success that necessarily makes us wonder how the studio pulled off such a feat. If you’re reading this book, there’s a good chance that you’ve asked yourself that very question. Does the success of The Last of Us come from the simple fact that it offers an engrossing and realistic story? From its convincing characters whose reactions are so surprising and ultimately so human? From its heartrending epilogue that leaves virtually all players feeling devastated? I think The Last of Us really owes its success to something simple: the emotions that it makes us feel. The two episodes created by Naughty Dog constitute one of those life-changing experiences in the life of a player. The kind of experience that can change your way of seeing the world. And the emergence of those very emotions is no accident. They are the result of a meticulous effort of manipulation–in the sense of storytelling–by Neil Druckmann, Bruce Straley, Halley Gross, and the rest of the Naughty Dog team. The precise, unparalleled work of artisans.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nicolas Deneschau is a lover of monster films and pirate novels. After initially focusing his attention on genre films, he lent his writing talents to the video game analysis website Merlanfrit.net. Nicolas now collaborates with Third Éditions. Notably, he is the author of The Mysteries of Monkey Island: Pirates Ahoy!, as well as the co-author of The Apocalypse of Godzilla: Japan’s Inner Monsters and The Saga Uncharted: Chronicles of an Explorer.

1. Diegesis is the universe in a work of fiction, the world that it creates, governed by its own original rules.

ACT 1: THE LAST OF US

Chapter 1: The goldsmiths’ workshop

“Story games are not movies, but the two forms do share a great deal. It is not fair to completely ignore movies. We can learn a lot from them about telling stories in a visual medium. However, it is important to realize that there are many more differences than similarities. We have to choose what to borrow and what to discover for ourselves.”

Ron Gilbert, Why Adventure Games Suck

Sic Parvis Magna

Long before the accolades, the praise, the money, and the pressure that comes with all that, the history of the studio Naughty Dog began to take shape in the early 1980s. Andy Gavin and Jason Rubin, two pre-teens from Northern Virginia, shared the same passion for video game arcades. On an Apple II family computer, the two friends would amuse themselves by recreating graphics, animations, and routines from video games that were popular at the time. They pirated, modified, and distributed copies under the table on floppy disks, passing the games off as their own creations when selling them at school. In February 1984, Andy and Jason even set about producing a complete copy from scratch of the Genyo Takeda arcade game Punch-Out!! They took photos of the movements of the boxing game’s characters, then spent several months drawing and programming every element of gameplay, until they ran into a catastrophe familiar to many a budding game developer at the time. The floppy disk containing the only version of the game broke, and they lost their data.

However, that setback didn’t dampen the motivation of the two young programmers in training, who supplemented their studies by creating a number of small programs, including Math Jam, their very first title published by their own company, which they named JAM Software (for Jason & Andy’s Magic). In 1986, the two young men began developing their first original game, Ski Crazed, a rudimentary obstacle course. They sold about 1,500 copies of the game at $2 apiece. It wasn’t a large bounty, but the two friends were very pleased. While they hadn’t made a fortune, Andy and Jason began to realize that they had an opportunity. Dream Zone, the second game from JAM Software, was much more ambitious. A text-based adventure featuring graphics combining digitized photos with pixel art, Dream Zone stood out in particular for its story and poetry. To top it all off, the game was a surprise hit, selling a little over 10,000 copies. Above all, Dream Zone was their ticket into the big league. Jason worked up the nerve to send a copy to Trip Hawkins, the head of Electronic Arts (Ultima, Bard’s Tale, etc.) at the time. In return, he received a check for $15,000 to produce the medieval-fantasy adventure game Keef the Thief in the span of a few months. The game was released in 1989 for the Amiga and PC. JAM Software officially became Naughty Dog. And that was just the beginning of a long adventure.

A talent for plagiarism

Trip Hawkins decided to place trust in Andy and Jason by offering them $150,000 to develop a new game for SEGA’s upcoming 16-bit console, the Genesis (Mega Drive in Europe), for which the development kit had just been provided to the publisher. Rubin and Gavin split their time between finishing their university studies and developing Rings of Power, an unusual role-playing game heavily influenced by Ultima and Wizardry, two popular games at the time, but with a camera perspective similar to Populous, the “god game” by Peter Molyneux that was the talk of the town in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. Already at that time, Naughty Dog was beginning to develop a signature. Both Andy and Jason were first and foremost video game fans and technicians; they didn’t see themselves as creators per se. Rings of Power was a melting pot of different recipes from its time, and that is precisely what would become the hallmark of Naughty Dog for many years. Far from the pretense of inventing, revolutionizing, or blazing a new trail for video games, the studio would instead try to coast on established formulas while adding their own special touch to the graphics, sound, animation, and simple, primal pleasure of playing. So, to support the release of the 3DO, the console that Electronic Arts attempted to launch in the American market in 1993, Naughty Dog once again shamelessly plagiarized the day’s best titles, which happened to be fighting games. In 1993, while Street Fighter II was drawing crowds to arcades, the 3DO graced screens with Way of the Warrior, an incredible, improbable, totally cobbled together title similar to Midway’s classic game Mortal Kombat. Digitized actors, amateur costumes, uninhibited humor, and ostentatious violence: the game was a pastiche lacking ingenuity that combined both a by-any-means-necessary attitude and a talent for hiding the game’s spectacular shortcomings. Most of the motion-capture scenes were performed by the actors in front of a white sheet in the small Boston apartment where Andy Gavin lived while studying at MIT. The fighters’ armor was made up of cardboard boxes and Happy Meal cartons from McDonald’s. Friends and family all pitched in to lend their likenesses to the game’s cadre of martial artists. Way of the Warrior created a bit of buzz at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas in January 1994, and Naughty Dog found a publisher for the game: Universal. The Universal team, impressed with what Andy and Jason could pull off on the cheap, offered them an exclusive contract for three games. Naughty Dog had successfully launched and would have the opportunity to grow.

Crash test

Continuing to apply the studio’s signature, the next game from Naughty Dog was a modest amalgam of the video game trends of the time. Modest, but incredibly memorable and successful. In 1994, the Super Nintendo delivered its swan song with the incredible Donkey Kong Country, a true gem for the platform, developed by Rare. At Naughty Dog, the team directed its attention towards a newcomer on the video game scene: Sony’s PlayStation. The polygons, the 3D graphics, the use of CD-ROM: Jason Rubin saw the potential, even if the sad fate of the 3DO suggested he shouldn’t be so optimistic. “What if we made a Donkey Kong Country in 3D?” With that, Andy Gavin established the concept for their next game. Aware of their technical and financial limitations, Naughty Dog didn’t attempt to start the open world revolution that Nintendo would ignite with Super Mario 64, instead faithfully transcribing the game design of the previous generation of platform games with an additional dimension, preserving the linear progression. Sonic’s Ass Game, as it was nicknamed by the small studio, took months of relentless work by the team of eight, from learning to produce 3D graphics to developing totally experimental controls, from using new graphics tools to dealing with a console whose possibilities seemed impossible to master. Crash Bandicoot, as it was finally named, was able to take advantage of an improbable confluence of circumstances. During 1995’s E3 trade show, SEGA unveiled Yuji Naka’s Nights into Dreams, to be released for the Saturn, and Nintendo made a splash with Shigeru Miyamoto’s Super Mario 64, while Sony showed up casually without a standard-bearer and without any images ready to show off to the public. So, the video game media had to do their work for them. Automatically conflated with the Sony PlayStation, Crash Bandicoot became the official fun and colorful character to represent the brand-new machine. It was a godsend and a fantastic promotion for Naughty Dog. Sony seized the opportunity and made sure to mention the game as soon as it could. Audiences almost immediately fell for Crash Bandicoot: it’s less technical than Mario, easy to pick up, and nice to look at, with its styling inspired by Looney Tunes. When the game was finally released on August 31, 1996, it quickly sold 2 million copies. An incredible success. Crash was even one of the first Western titles to become a hit in Japan, an extremely rare feat. Not an ounce of originality, no astounding creativity, not at all revolutionary, just a little well-crafted game without immoderate ambitions, but made with loving, almost artisanal expertise, arriving in the right place, at the right time. Of course, Sony and Universal made sure to capitalize on the game’s success. Between 1996 and 1999, four installments in the Crash series hit the shelves. The Naughty Dog team grew accordingly to around 40 employees, making the California-based studio the biggest bunch of amateurs, in the words of Jason Rubin. The company had an ambiance of camaraderie, pizzas, and Coca-Cola; they worked a lot and played a lot, but meanwhile, the video game industry continued its ascent.

Adulthood

The industry grew, and the stakes and pressure grew with it. For Sony, the entry into the new millennium meant the arrival of the PlayStation 2. Between this loss of innocence and the technical difficulties encountered in working with the new console, Andy Gavin began to feel it was time to move on. In January 2001, Naughty Dog nonetheless presented its project Next to the heads of Sony, who decided to deliver the funds needed for the game’s development by simply buying the studio. From then on, the “Dogs” would belong to the inner circle of the Japanese console maker, a particularly visionary and redeeming position for them to be in during a decade that saw a growing divide between small teams in danger of extinction on the one hand and large-scale professionalization of the industry on the other. The only thing that Naughty Dog would have to worry about was making not just good games, but great games.

This new era gave birth to Jak and Daxter. Influenced by what the team had learned from Japanese productions and sporting a fun, colorful, more Western design, the studio’s new game met once again with spectacular success without doing anything particularly inventive, but simply by enhancing an existing formula. The title again stood out for its technical excellence, its user-friendly, fluid controls, and its lack of loading time–a technical feat at the time. To achieve such a result, the team’s in-house engine, GOAL, demonstrated unprecedented ingenuity. Indeed, some of the components included in the PS2 were there to allow backward compatibility with older games from the PS1. This gave Gavin the idea to develop program routines that would operate certain game elements directly through the processor dedicated to PS1 backward compatibility, in addition to the resources dedicated to the PS2 itself! As such, GOAL was a hybrid game engine bridging the gap between the two console generations, producing impressive results on screen.

From 2003 to 2006, the Jak and Daxter series once again received four installments that achieved satisfactory success, even if that success steadily declined from the first episode to the last. Each title was another little baby for the studio, produced with painstaking effort. The team faced tight deadlines and their motivation slowly withered away. Finally, Andy Gavin and Jason Rubin, having reached the point of exhaustion, threw in the towel. The studio was in a crisis. It would have to reinvent and reorganize itself while working with new hardware, the PlayStation 3, which would be released in November 2006.

The Naughty Dog formula

While it’s interesting and important to examine the genesis of Naughty Dog and its earliest hit series, Crash Bandicoot and Jak and Daxter, it was really from 2007 onward, with the release of Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune, that the pieces of the puzzle constituting The Last of Us began to fall into place. Starting with the action game following the adventures of Nathan Drake and his friends, each title and every detail would serve a singular purpose: to refine the “formula,” one that would advance and improve to the point of reaching its acme in 2020’s The Last of Us Part II.

The internal turmoil generated by the departures of Andy Gavin and Jason Rubin, along with a number of members of the studio’s old guard, had a major impact on the development of the new franchise to accompany the release of the PlayStation 3. Leadership of the studio fell to Evan Wells, formerly of Crystal Dynamics, who had already been with the Dogs for a few years. Before long, he was joined by Christophe Balestra, a young Frenchman who had become one of Naughty Dog’s technical gurus. Placed under the expert management of Amy Hennig, development of Project BIG underwent several transformations, both in terms of its design and its ambiance, before finding its sweet spot. For the website Gamasutra, Bruce Straley, who would be the future co-director of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, summed up the general concept of the new franchise thusly: “We set out with a specific goal of making a playable summer blockbuster. This was almost our motto from the beginning of production: How do we take those epic action sequences from films like Die Hard, Terminator 2, or the Indiana Jones series, and keep the player in full control? We all just love those films and the feeling you have when leaving the theater after a great summer matinée, and we thought to ourselves, ‘Wow, what if you could play that? ‘ In addition to the action, can we have the heart and emotions of those movies as well? You know why Ripley is willing to sacrifice so much in Aliens, and you care. We wanted players to fall in love with our characters, to care about what happens to them and about their relationships.” This idea would not just form the new orientation of the Uncharted series; it would redefine the overall trajectory of the studio in the years to come, with Naughty Dog undeniably shaped by the project’s exceptionally influential female director.

Amy Hennig

After earning a bachelor’s degree in English literature from the University of California, Berkeley, a young Amy Hennig decided to pursue film studies at San Francisco State University. In 1989, finding herself in a difficult financial position, by pure luck, she got her first job working as a freelance artist for Atari. She started by working on ElectroCop for the Atari 7800, an action game that was never actually released. Still, for Amy, it was a revelation: the video game medium opened up infinite unexplored possibilities for her. While she had been passionate about film since she first saw Star Wars: A New Hope on the silver screen in 1977, she sensed that breaking into a male-dominated industry would depend more on who you know than on your actual artistic abilities.

Indeed, a woman’s presence was treated as an oddity, or even with suspicion. However, she was tenacious and was hired by the industry giant Electronic Arts in 1991. Two years later, she got a break when an art director left the company and she was promoted to take his place working on the title Michael Jordan: Chaos in the Windy City. The game was a success, but the opportunistic and forced incorporation of the basketball star to promote the game was viewed as a total waste. Still, Hennig used the game as an opportunity to climb the ladder one rung at a time, making her one of the very few women to hold a management position in the video game industry. In the late 1990s, she seized a new opportunity at Crystal Dynamics. Notably, while there, she met Richard Lemarchand and Bruce Straley. They worked together on a first-rate title, Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver (the 3D sequel to Blood Omen, developed by Silicon Knights), that was life-changing for owners of the first PlayStation. Making excellent use of the environment, much like the revolutionary Tomb Raider, and presenting impressive direction and multiple twists for the colorful characters, Soul Reaver was a top-notch success and a springboard for Amy Hennig.

She went on to direct two more games (Soul Reaver 2 and Legacy of Kain: Defiance) before joining Naughty Dog, which had been trying to woo her for some time. She joined the California-based studio as an ordinary developer in 2003, working on Jak 3. Before long, she put together a core team and, starting in 2005, they began working on a new license that would be released alongside Sony’s next generation of console. The game was given the code name Project BIG.

Working as a creative director at Naughty Dog throughout the entire Uncharted saga, Amy Hennig, with her one-of-a-kind personality characterized by her finesse and her sense of fun, thus followed an unusual career path as a strong woman in a male-dominated world. From 2003 until her surprise departure from the studio in 2014 in the middle of production of Uncharted 4, Amy Hennig embodied the series and imposed unprecedented quality standards that redefined how storytelling could be integrated into gameplay, forming the very essence of the series.

Over the span of a decade, from 2007 to 2017, the Uncharted saga became increasingly refined and improved its formula consisting of meticulously blending pure action scenes with cutscenes and story-driven sequences. The watchword “blockbuster” sums up quite nicely the goal of each new production. Naughty Dog wanted to tell stories and create fun games that could be “experienced” in one sitting. Faithful to its history as a copier of genius concepts, the studio would steal good ideas from all over without trying to do anything revolutionary. Instead, Naughty Dog aimed to highlight its technical prowess and its talented craftsmanship. Sony needed “flagship games” to sell its machines; the studio would brilliantly deliver on that order by carving out a high-quality niche for itself among AAA productions.

Interactive movie

Before we really get into the genesis of The Last of Us, I feel that it’s important for me to address one of the biggest grievances leveled against Naughty Dog’s games. To do so, allow me to go on a personal tangent for just a moment. It’s almost an involuntary reflex at this point, but every time I read or hear a negative comment about the trend of Naughty Dog’s titles, whether Uncharted or The Last of Us, being nothing more than crude (barely) interactive movies, I retort with the same response, an analogy that has stayed with me for almost as long as narrative video games have existed. The story begins in 1986. I was seven years old and in CE1, the equivalent of second grade in American schools. At the time, the World Cup was fast approaching and like all the other kids in my neighborhood in a far-flung suburb of Paris, my friends and I would get together after school and take over whatever bit of paved surface we could find to play soccer. As the French national team, led by Platini and Battiston, racked up victories, each recess was entirely dedicated to reproducing their matches in the schoolyard. The ball would come out and we would quickly get back into teams. Our 10-minute break was all we needed to gleefully score over a dozen goals. It was late in the school year, every little boy was obsessed with soccer, and all of us had become experts in the field. Mastering our passing and dribbling skills was taken much more seriously than reading or multiplication tables.

After our two months of summer vacation, when I returned to school to start CE2 (third grade), I watched as the boys sprinted to the schoolyard’s improvised soccer field and split into teams. But this year, a new face appeared in the group. Mathieu’s parents had just moved to town. His dad was actually the new head of one of the two local movie theaters. Mathieu and I quickly became friends and he joined our modest little team of recess soccer players. While all the other boys put great effort into bouncing the ball around in a sort of juggling act, with varying levels of success, Mathieu’s thing was to tell stories. One afternoon, he told us all about this new movie starring Tom Cruise that had just come out called Top Gun. He mimed the confrontations between the US Navy’s F-14 jets and the Soviets’ MiG-28s, throwing in lots of gestures and sound effects. We were amazed. He grabbed our soccer ball and instead of launching into a dribble, he made up an entire story blending together Highlander, Russian secret agents, and legendary pirate treasure. From then on, our little team would get together each recess to continue the adventure. We crossed over deep chasms, climbed snowy mountains, battled enemies with imaginary pistols, and protected our precious soccer ball at all costs. With Mathieu, a whole new world of games opened up for us. His talents as a narrator were such that waiting for the next part of the story was torture. And that kid knew exactly how to toy with our ability to be amazed. The rules of our game may have been less technical, fair, fine-tuned, and thought-out than the rules of soccer, but that wasn’t the point. The stakes were low and the competition was artificial or even non-existent; no matter. The stories that Mathieu came up with had almost no point to them and were really just barely disguised knockoffs of the films he’d seen recently at his dad’s movie theater; but that didn’t matter either. No. What we enjoyed was experiencing those thrilling adventures together. Each kid got to play a key role in the adventure and soaked in the words of our narrator. Sometimes we would try to change the script, but Mathieu would typically set us straight within a minute. He was the storyteller and he allowed us to embody the characters that he imagined. It was a totally new way for us to experience a story. We became part of his imaginary universe. And what amazing adventures we went on!

Over three decades later, I find that the critical lens through which video games are viewed remains as rigid as ever. A rigidity that a bunch of kids very naturally destroyed while playing in their schoolyard. The medium has constantly been bogged down by rules and limitations, little boxes defining the critical contours of video games. Naughty Dog’s games have found themselves in the overlap between two worlds that have long eyed one another. On the one hand, there’s the straightline story games and interactive movies, and on the other hand, there’s the classic technical action game. That is precisely both the studio’s strength and weakness. Mainstream, dazzling, universal, but not technical enough for some, and not offering enough freedom for others. It all depends on what kind of kid you are, your capacity for being amazed, your willingness to be guided on a journey. Since 2007 with the release of the first Uncharted, Naughty Dog has gradually refined its formula. Of course, it may be imperfect and rigid, even questionable. But without a doubt, Naughty Dog aims to be a new schoolyard storyteller and puts all of its fantastic talent into achieving that.

Chapter 2: The roots of all evil

“Story in a game is like story in a porn movie:it’s expected to be there, but it’s not that important.”

John Carmack, creator of Doom

A video game in service to a story

Independent of its most pragmatically technical, or even mechanical, aspects, a work of art, no matter the medium, is the result of a creator’s vision and message. The seven “classic” arts, according to the definition established by philosopher Étienne Souriau in 1969 (i.e., architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, music, theater, and film), lend all of their virtues in service to the artistic vision of one or more creators. In this respect, video games have always distinguished themselves. Since its earliest days, the medium has been afflicted by an internal conflict, a sort of ambivalence. While creators initially conceived of video games as a pastime, mainly oriented towards action and maneuvering, in the mid-1970s, the medium gradually moved in the direction of storytelling. First, text was used as the game interface; then, under the influence of film and thanks to technical improvements in graphics and sound, most of the story was conveyed through images and action. Video games worked off of forms of storytelling inherited from the classic standards of film and literature.

It’s hard to pin down a precise date, but it was probably around the early 1990s that storytelling began to play a dominant role in most video games. This sudden focus on story in a medium very much centered on fun created a schism among industry observers. Researcher Gonzalo Frasca theorized about this conflict in his 2003 essay Simulation versus Narrative: Introduction to Ludology. In his paper, Frasca describes two opposing camps of thought: “narratology” and “ludology.” For narratologists, video games offer a new form of narrative expression, combining features of the “classic” arts of film and literature. In their view, far from simply being limited to entertainment, video games offer a new possibility for immersing the player in a story by telling it in a different way. Conversely, for ludologists, story is not the primary objective of video games, or at least story should necessarily be conveyed through gameplay, as that is the very essence of a game. As such, a player of Pong could create their own story around an eminently basic game system. On the one hand, video games are thought to tell a story established by a creator; on the other, the player is supposed to invent their own story out of the game.

For the video game industry, this schism in theory translated concretely to critics’ perception of the medium. Initially, games were essentially judged on the quality and originality of their gameplay. Gradually, the importance of storytelling in video games forced a paradigm shift and changed the criteria used for evaluation by the press and even by players. However, the underlying problem remained. Did video games really offer a true storytelling tool distinguishing them from their glorious ancestors? Could video games deliver emotions and tell stories without simply mimicking film?

French researcher Sébastien Genvo offered some interesting food for thought in his essay Le Game design de jeu vidéo: approches de l’expression vidéoludique (Game design in video games: approaches to video game expression). According to Genvo, a video game naturally tells a story conveyed exclusively through its gameplay. The story arises from the interpretation of commands. There is an entertainment-related result of manipulating the mouse or controller–pressing a button to jump or to stab a boss with a sword–and there is the narrative result of the same action–getting up, moving up, hitting or killing a character. Every action can have a controlled narrative result if it’s deliberately designed to serve a function in the story. As such, little by little, the interactive features were no longer perceived as being diametrically opposed to storytelling; instead, they came to be seen as a whole new artistic means of telling a story.

This striving for narrative gameplay in its purest form became the obsession of a movement that spread far and wide in the 2010s. What we now call “indie” video games quickly staked their claims on that fertile ground. Memorable gameplay-storytelling “experiences” would become clear, concrete examples to back up the theories of Frasca and Genvo: Fumito Ueda’s ICO (2001), Jonathan Blow’s Braid (2008), Jenova Chen’s Flower (2009) and Journey (2012), Markus Persson’s Minecraft (2010), the list goes on. Firmly more conservative, the big-budget segment of video game productions–the “AAA” games–nonetheless enviously eyed the ingenuity and the collection of tools that emerged from this new wave of creativity. While some productions continued to focus more and more on the richness of their universes and quality of their writing, as in the case of Naughty Dog’s Uncharted, the incorporation of cinematic elements, while done proudly, was incomplete, and the artifices of gameplay continued to interfere with storytelling. By the end of the aughts, there was still not a single AAA game to fully incorporate these concepts into both its gameplay and storytelling. Like any artistic medium, the video game needed an author, a creator, and, if possible, an artist who had fully absorbed the evolutions coming out of the new wave.

The storyteller

Interestingly, Neil Druckmann wasn’t always a computer guy. When he started university, he majored in criminology. “And then at some point, I took a programming class, and it came easy to me, and then it just clicked, ‘Wait, this is what people do to make video games! ‘” That’s right: before joining the prestigious Naughty Dog studio and writing The Last of Us, Neil Druckmann imagined following a very different career path. “I thought I was going to be an FBI agent, that’s how silly I was,” he told Edge magazine in 2013. “Originally, I grew up in Israel. And I lived there for ten years before my parents decided to move to the US, and then I went to middle school and high school in Miami, Florida.” While most young immigrants learn English in school or from TV shows, Neil Druckmann developed his skills in the language through another medium: the video games that his brother would share with him on their family computer. “I learned most of my early English through computer games. While still abroad [living in Israel], I spent countless hours playing the old Sierra and LucasArts adventure games. I played everything from Maniac Mansion to Space Quest; and since these games required a substantial amount of English to play them, I ended up picking up quite a bit of it in the process,” Druckmann shared on the blog he wrote while still a student at Florida State University. Again, for a while, Neil Druckmann majored in criminology, but then instead decided to try his luck with a degree in computer science. “Then I moved to Pittsburgh, where I went to Carnegie Mellon [University] and got a master’s degree in Entertainment Technology, which is this weird major that combines storytelling with programming and art.” While at CMU, Druckmann cut his teeth in the video game world by working on a variety of small, amateur productions, including a first-person shooter entitled Pink Bullet, a clone of Super Mario Bros. called BearDay, and, most interestingly, a full-fledged game for Nintendo’s ancient NES console dubbed Dikki Painguin in TKO for the Third Reich, in which a ninja penguin uses his sword to chop Nazis to bits on apocalyptic backgrounds reminiscent of classics like Tecmo’s Ninja Gaiden from 1988.

After earning his master’s, in 2003, things really started coming together for Neil Druckmann. As in all great stories, our hero would start from humble beginnings. In 2003, during the prestigious Game Developers Conference (GDC) in San Francisco, an annual gathering of the cream of the crop of video game creators, Neil attended talks by Randy Smith (Thief), Ted Price (Spyro, Ratchet & Clank), and Will Wright (The Sims, Sim City), as well as one Jason Rubin. While Rubin spoke, the young aspiring developer began to see a glimmer of his calling in life. In his talk entitled “Great game graphics… Who cares?,” the co-founder of Naughty Dog, which had been a subsidiary of Sony since 2001, explained to his audience that the technical evolution of consoles and other gaming hardware was pushing studios to focus mainly on the graphics and special effects of their video games. For Rubin, the true strength of smaller studios was their boldness. He argued that captivating audiences by creating games that were increasingly engaging on an emotional level was the key. For Neil Druckmann, that argument was music to his ears. He immediately seized his opportunity. When Rubin finished his talk, “I approached him and I bugged him and I told him that I wanted to break into games. He foolishly gave me his business card, and then I started just bugging him and sending him my portfolio,” Druckmann told a journalist from the website CreativeScreenwriting in 2013.

The next big milestone. Just a few weeks later, Emmanuel Druckmann, Neil’s brother, took him to E3, the video game industry’s biggest event, held in Los Angeles. The stars of the show were id Software’s Doom 3 and, in particular, the impressive technical demo for Valve’s Half Life 2. But Neil made a beeline for the Naughty Dog booth, where the studio was presenting Jak 2. There, he met Jason Rubin a second time. Impressed by the young man’s perseverance, Rubin invited Neil to come interview for a job at the studio’s office in Santa Monica. After a formal meeting with Evan Wells, who at the time was the head of the development team and who would later become the co-president of Naughty Dog, Neil Druckmann had the extraordinary honor of being hired on the spot as an intern at the studio. It was quite a rare move for the company, which generally preferred to hire independent contractors so that it could expand its workforce according to the needs of projects and the financial situation of the company. That said, Druckmann (gladly) paid a price for that privilege, with the expectation that he be ready to work constantly. For the production of Jak 3 (2004) and Jak X Combat Racing (2005), working as a developer, the young man would spend his evenings in front of his computer screen, trying to sort out hundreds of lines of code, to the detriment of his personal life. Still, he worked hard, and before long, it paid off.

In 2004, the departure of the company’s two historic leaders, Jason Rubin and Andy Gavin, completely upended the studio’s management. Christophe Balestra and Evan Wells took the reins as best they could amid the confusion and a tense atmosphere. Having a close relationship with Wells, Neil Druckmann was given a key role on the prestigious design team, the group in charge of coming up with and designing universes, gameplay, and the major orientations of the studio’s games in development. Druckmann’s new position moved him away from the more technical side of development and his lines of code. “I’ve always been more interested in the storytelling aspects of games as something I really wanted to pursue and push. Eventually, I was able to convince the powers that be at Naughty Dog to give me the chance to do that. So, I moved over to the creative/design/writing side, and that’s when I started working on the writing of Uncharted 1. I worked closely with Amy Henning on structuring the story and writing some of the scenes.” However, Neil Druckmann didn’t have any particular experience with writing; on that point, he adds, “I’m lucky in that I started my career at Naughty Dog, which has always been very story driven, very character driven.” And clearly, in 2004, the studio rapidly pivoted towards this new approach to video games focusing essentially on storytelling and cinematic qualities. Moreover, the studio had an ideal location in Santa Monica, California, being very close to Hollywood. Several members of the team regularly attended talks given by heroes of Hollywood storytelling, like John Lasseter (Pixar) and J.J. Abrams (Lost, Star Wars VII). “We’re constantly trying to refine our craft, trying to think of ways of using less exposition, making it more character driven, [and] thinking about arcs.” Thus was born the studio’s mantra, “character-driven experience.”2

The pillar

“I’m Bruce Straley. […] I make video games. […] I game-directed […] Uncharted 4, co-directed with Neil Druckmann, and then prior to that, I co-created and co-game directed […] The Last of Us. And then before that, Amy Hennig did the creative director role and I had the game director role on Uncharted 2. Prior to that, I was the art director for Uncharted 1, and then the Jak and Daxter franchise. I’ve been at Naughty Dog for, I don’t know […] coming up on 18 years,” the co-director of The Last of Us told Maciej Kuciara (Art Cafe) in a 2017 interview. In a perpetually evolving industry, particularly at Naughty Dog, a studio that’s no stranger to upheaval and reorganizations, Bruce Straley is seen as a veteran, a pillar. Unlike Neil Druckmann, his future colleague, Bruce discovered his calling in life after formally studying art. Responding to a question about whether there was a particular moment where he realized what he wanted to do in life, Straley said, “I think that’s a modern concept, pursuing your dreams. For me it was–I did go to art school, but it was only because my mom kicked me out of the house and she was like, ‘you’re going to school.’ And so the only thing I was good at was drawing. […] I [drew] and painted every day for a couple years.”

After finishing art school, he moved out to California and, while he saw himself working in advertising, he actually got his first professional experience working for a small company called Western Technologies Inc. In 1992, the first game he worked on that got published was Menacer 6. It was a collection of mini-games put together on a single SEGA Genesis (a.k.a. Mega Drive) cartridge and distributed by SEGA of America. From there, Bruce Straley continued to gain experience, working on the backgrounds for several SEGA Genesis titles, including X-Men (1993) and Generation Lost (1994). “It is funny, there are people in the industry who, when they find out how long I’ve been making games–I’ve been in the industry since 1991–[…] there’s people who are like, ‘I was six years old when you made your first game.’ […] And I’m like, ‘That doesn’t make me feel very good.’” In 1994, he joined the team at a studio called Zono, designing the category-defying Mr. Bones (1996) for the SEGA Saturn. One day in 1996, he happened to come across a game called Pandemonium!, a spectacular 3D platform game from the heyday of Sony’s original PlayStation. On the back of the game box, he read the name of the developer: Crystal Dynamics. He decided on the spot that he was going to work there. And nothing could stop the intrepid artist: just a few months later, in early January 1997, Bruce Straley packed up his desk and moved into a large office at Crystal Dynamics, just south of San Francisco, where he would work alongside one Evan Wells.

Straley found himself surrounded by passionate people and inspiring specialists. He first worked as an artist on Gex: Enter the Gecko (1998), a 3D platform game with a cartoon style for the Nintendo 64. He then worked on Gex 3: Deep Cover Gecko (1999), for which he diversified his skills and began mastering, little by little, certain aspects of modeling, animation, and, most importantly, optimization. “It takes a long time to become good at anything you attempt to do, right? […] My experience shows, like, doesn’t matter how big my ego is, what I think I know. Every single project, every single year, I learned something new. And I think as long as we’re still being challenged… it just takes a long time to do anything, you know? To learn anything.” Bruce Straley was lucky to be part of the talented team at Crystal Dynamics working on the future cult classic Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver with Amy Hennig. Straley remained humble and watched her work. He worked long hours, learned a lot, and perfected his skills. Meanwhile, Evan Wells had left Crystal Dynamics to go work for the young but already prestigious studio Naughty Dog. Wells offered Straley a job as an in-house artist with a pretty healthy salary. So, in 1999, Bruce Straley left the San Francisco Bay Area and moved to Los Angeles.

While Naughty Dog had already earned accolades, it was still a small studio. Straley immediately put his talents as an artist to work by helping finalize the game Crash Team Racing (1999). From there, he continued developing his skills by simultaneously serving in different roles: an artist specializing in textures; a designer, establishing the look of Jak and Daxter: The Precursor Legacy (2001); a background artist… the list goes on. Over the course of several installments in the Jak and Daxter series, Bruce Straley proved to be a crucial link between the studio’s artists and developers. The particular technical constraints of the PlayStation 2 required rigorous work and optimization at all times from the team members working on the modeling of characters and backgrounds. And the artists and technicians did not find it easy to work together. Each side believed that they had the most important job. On the one hand, the artists wanted to make the world’s most visually-stunning game; on the other hand, the developers were focused on making the game’s animations fluid. A cold war began between the two camps over the optimization of the graphics engine for Jak and Daxter, which, as we already know, went as far as to exploit the console’s chip intended for running PS1 games. Unexpectedly, Straley was able to intervene and translate the needs of each side. He served as a sort of negotiator, faithfully maintaining his neutrality. Most importantly, the team quickly recognized his ability to settle things when thorny decisions had to be made.

As a direct consequence of the studio’s reorganization following the departures of Andy Gavin and Jason Rubin, Bruce Straley was promoted to the role of art director for the studio’s next big project: Uncharted. “For us in production on that game, we learned a lot about what not to do. And that has to do with, we took on, one, new technology, because we came from the PlayStation 2 to the PlayStation 3, and for some reason we just thought that the PlayStation 3 was going to be able to fly spaceships to Mars and solve world hunger. It was going to be the solution for everything.” After many departures of staff members, Naughty Dog was getting back on its feet under the leadership of Christophe Balestra and Evan Wells, with new ideas and unbridled ambition. However, they soon ran into a roadblock: “So, we hired a bunch of people from the film industry who had never made games. […] We had programmers–people who, like, they did The Day After Tomorrow