Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Third Editions

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

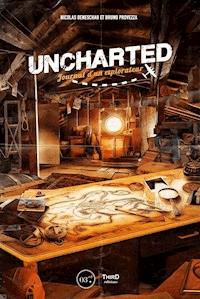

In movies, defining a 'classic' means judging the quality of a director, the acting of the actors or the value of a script. But when it comes to video games, which are inextricably linked to technological evolution, it is not so easy to predict which games will age well and stand the test of time. Uncharted has the feel of a classic grand adventure, with thrilling action and great dialogue. One thing is certain: few video game series have earned that label. Mixing a form inherited from the Hollywood pulp classics with great writing made the saga instantly enjoyable, thrilling and exciting. In addition to discovering the secrets of the creation of each title in the saga, you'll also be able to immerse yourself in its universe and discover its historical inspirations. A way to create your own adventure.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Couverture

Page de titre

For Antoine, my own little adventurer… Nicolas

PREFACE

If you’re reading this book, it’s because the pockets of your sun-worn leather jacket still contain traces of dust from the Rub al-Khali desert. Because the skin on your hands tells of weeks spent meticulously brushing the tiniest rocks found in an ancient ruined city lost in an oppressive jungle. Because the smell of long-forgotten books of spells and improvised torches are no stranger to you. Because none of your injuries, nor your collection of scars, would ever be enough to stop you exploring or extinguish your blind passion. And it’s probably because you never stray too far from your Colt and your DualShock controller. Know that you are not alone. Not by a long shot.

When the idea of a book about the Uncharted series first took root in our minds, we saw it as a fresh opportunity to take a deep dive back into these games that marked the glory days of the previous two PlayStation consoles. The spiritual successor to Indiana Jones, brainchild of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, Nathan Drake bears deliberate similarities to the character that inspired him. Jones and Drake are both unflinchingly confident, even in the most extreme circumstances ; both possess a sharp sense of humor, even in the most trying of times ; both have a propensity for destruction when it’s to preserve history ; and both have a particularly energetic approach to archeology. Most of all, though, they both have a questionable talent for preservation, with their adventures invariably ending with the destruction–voluntary or otherwise–of the very same treasures and wonders they set out to discover.

Elena, Chloe, Sam, Sullivan… over the course of the series, encounters with his friends and companions in misery flesh out the picture of what it means to be Nathan Drake. The self-proclaimed descendant of a famous British explorer of the same name, a rogue, a scrapper, a charmer, lucky, lovable, and sometimes melancholy… the Uncharted series tells the story of one individual man, more than any other video game that came before. But rather than having us play as the main character, Naughty Dog’s series instead invites us along to join him on his adventures. It whisks us off around the world on some hair-raising adventures, destroying priceless ancient relics and blowing up just about everything in sight… and always with a smile in the company of his amazing team.

While our main aim in writing this book was to reveal the secrets of how each game in the series was made, we would be over the moon if we could also evoke some of the atmosphere and interests that first led readers to buy one of the games. With that in mind, we have tried to dig deeper into the game world and explore its real-world historical inspirations. You’ll come to see that actual history has nothing to envy the adventures of our protagonist and that the real world is home to just as many incredible destinies and outlandish mysteries as those depicted in Uncharted.

As intimate as it is fantastical, Naughty Dog’s series was our joy and our obsession in equal measure. All it takes is for us to hear a few particular notes of music and we want to head back out to discover unexplored lands…

The Authors :

Nicolas Deneschau

An avid devourer of Kaiju-Eiga monster movies, black and white Sci-Fi, and pirate novels, Nicolas is still trying to find his rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle. After a stint in the movie world at Cinegenre.net, he honed his writing skills at Merlanfrit. Today, he works with Third Éditions.

Bruno Provezza

Bruno Provezza has been an aficionado of video games and fantasy movies from a very young age. Between 2002 and 2006, he was the editor-in-chief of the official website of the Mad Movies magazine before joining the writing team on the monthly print edition. He also managed their special edition dedicated to video games. He has also worked as a translator for publications by Flammarion and Pix’n Love. He is co-author of Resident Evil. Of Zombies and Men, Welcome to Silent Hill. A Journey into Hell, and Professor Polymathus in a Brief History of Video Games, all published by Third Éditions.

CHAPTER ONE :WHO LET THE DOGS OUT ?

“Sic parvis magna”(Greatness from small beginnings)

Sir Francis Drake

dURING an interview with the American video gaming website IGN, Tate Mosesian tells the story of his first days at Naughty Dog back when he joined the company in 2002 : “There was something tangible when you walked through the door and sat down to start working. There was never any doubt that what you were working on was going to be finished and it was going to be good […] Everything was very professional regarding the production of the game. Everything else was total chaos […] There were a lot of people strewn around. There wasn’t any real organization… It just didn’t seem like that triple-A studio from first impression.” Mosesian didn’t even have a computer waiting for him on his first day. On the second day, one was at his desk, but it was covered in food and stains. “Well, yes, it would have been nice to not have to clean spaghetti sauce off of my keyboard, but it was nice to be working in a studio that did such great work, but also maintained this crazy garage mentality. This bunch of guys just working on something awesome. That was actually really cool.”1

It’s rare that the very name of a studio causes such a rapturous reaction. It’s even more surprising that its very mention elicits so much praise and a stream of superlatives, not to mention its reputation coming to signify a mark of undeniable success. Within the golden circle of developers working on triple A titles, and as the studio that dreamed up the Uncharted and The Last of Us video game odysseys, Naughty Dog is today synonymous with technical perfectionism and a quest for excellence at every stage of a game’s creative process. Each new Naughty Dog release is as much an event for the manufacturer that supports them (Sony, in this case) as for gamers the world over who consume each of its games in droves.

It’s also surprising that the company that may well be the biggest of Sony and PlayStation’s in-house studios would have such an unusual backstory. Indeed, the story of Naughty Dog goes hand in hand with the history of video games itself. Naughty Dog is a studio that stands out from the rest of the industry for its identity, culture, and chummy atmosphere. Its story unveils a particular vision of the American Dream : two young guys who began making games in the basement of a small Virginia home.

A PIVOTAL ENCOUNTER

In early 1980, as The Empire Strikes Back hit the movie screens and an entire generation learned that Luke was his father’s son, Donkey Kong, Frogger, Defender, and Galaga were rolled out in arcades. In northern Virginia, Andy, Jason, and a handful of other kids bonded over a shared passion for video games. Beneath the gentle sun of the American East, they spent their afternoons basking in the fluorescent lighting of video game arcades, spending all of their savings on trying to beat the latest high scores.

They all had a thing for pixels and the Apple II. The jewel of its creator, Steve Wozniak, this precursor to the PC could be used for simple programming in Integer BASIC or Applesoft, which were easy to use and open to all. Quiet and reserved, the young Andy Gavin was a perfectionist when it came to code. For two years on his Apple II, he developed unpretentious yet technically remarkable little games. With a more fiery character, Jason Rubin was the artist of the group. Despite the lack of a mouse and only a basic keyboard, he spent hours working his craft. Although of radically different temperaments, the two young Virginians soon came to see that they had complementary skill sets. But they were still far from suspecting that their common interest would lead them, a few years later, to found one of the world’s most successful video game studios enjoying a global reputation.

The first forays of this band of Apple II enthusiasts were initially limited to pirating games bought by their friends. With mass computing still in its infancy, finding ways to get around the protection–however rudimentary–of these games on floppy disk posed a real technical challenge. But the lack of information didn’t stop them, and they got a kick out of altering the games’ source code to write their names in the end credits and imagining they were the biggest names in video games. In February 1984, Punch Out !! (a boxing game by Nintendo) hit the arcades and our friends decided to begin work on a major endeavor to make an almost carbon copy of Genyo Takeda’s game. They took photos of each of the characters’ movements, and once again delved into the game’s coding in a process that lasted months. Just when they were entering the final stages of their project, disaster struck : Andy accidentally wiped the disk on which the only copy of their game was saved. With this stroke of fate, Andy and Jason’s Punch Out !! project was over.

A PROMISING START

Thankfully, this tragedy did nothing to dampen the two young programmers’ enthusiasm for their craft. In late 1984, they began work on an original program : Math Jam. As a piece of educational software, it was far removed from Andy and Jason’s predilection for entertainment, but the genre was in fashion back then as the market sought ways to win over parents and find a way into their homes.

Jason’s father, a corporate lawyer, helped the two young developers to start their own company–JAM Software, for Jason & Andy’s Magic–and develop their first project. As the name implies, Math Jam served up a fun way to learn the basics of arithmetic, with a design tailored to kids. After receiving the blessing of a few local teachers, the entrepreneurial duo was able to sell their first game. They copied the program onto floppy disks, inserted some basic instructions, put everything in envelopes, and mailed them to a few local schools. To sell the program on a larger scale, however, the US Department of Education required JAM Software to appear before a panel on the other side of the country so that their game could be approved. At that point, Andy and Jason gave up and decided to return to their first love, video games.

In 1986, JAM Software published its very first real game : SKI Crazed. The original title, SKI Stud, was soon changed to be more politically correct. The aim was simple : hurtle down snowy slopes while avoiding the obstacles that littered the player’s path. The animations and graphics were particularly polished for a production of this level. To achieve such a fine result with such rudimentary hardware, Jason used the editor from another program : Pinball Construction Set. It enabled him to draw the characters and environments in more detail… still without a mouse and using the extremely limited resolution of the monitors of the day. This ability to squeeze the best out of the resources at hand would become the hallmark of Naughty Dog : there is always a workaround for every technical challenge. SKI Crazed was picked up by a small publisher from Michigan, Baudville, and, generating $2 per copy sold, it became the two friends’ first stream of income, going on to sell around 1,500 copies. This represented a fortune for the two friends, who could finally make their first major investment : a hard drive…

In Virginia, Andy and Jason graduated from High School and each set off to a different college. Despite the distance–Jason was studying in Michigan and Andy at Haverford College in Philadelphia–they maintained their JAM Software project and developed Dream Zone, again published by Baudville. Dream Zone was a more ambitious adventure game combining digitalized images and drawings, in which a kid explored the weird world of their own dreams. The game’s interface was inspired by the earliest text-based adventure games, and once again the game’s production values were outstanding, from the music all the way through to the graphics. This was also the first time that Jason and Andy worked to polish the game’s story, an endeavor underpinned by the game’s dreamlike atmosphere. Dream Zone turned out to be a critical success, selling just over 10,000 copies and earning $17,000 for its creators. At the age of just seventeen, this was a real bounty for the precocious developers, and it served to fuel their now limitless ambition.

EVERY DOG HAS ITS DAY

This ambition was what led Andy and Jason to terminate their relationship with Baudville, a small-scale publisher, and go knocking on the door of Electronic Arts. In 1987, the company founded by Trip Hawkins (a former Apple employee) was already a global giant, producing, distributing, and publishing hit franchises (Ultima, The Bard’s Tale, Skate or Die !). Brazenly, our duo sent a copy of Dream Zone to one of Electronic Arts’ decision-makers in California. When a response finally came, it was straight to the point : “We’ll send you a contract.” With a check for $15,000 in the bank and royalties of 10 % on sales, Jason and Andy reworked the foundations of Dream Zone to create Keef the Thief, a medieval fantasy adventure game. The game hit the shelves in 1989, released on PC, Amiga, and the Apple II under the banner of Naughty Dog, the studio’s new name that the two friends had dreamed up during the development process. Although they delivered what was promised to Electronic Arts, the two creatives were not happy with the development conditions. Deeming the game too serious, the firm from Redwood had ordered them to inject some humor into it. This, however, went against the atmosphere and tone that Jason and Andy wanted to give the game.

In the end, though, the producers at Electronic Arts implicitly acknowledged that the changes they had imposed on Keef the Thief didn’t really result in a higher quality product. This meant that Andy and Jason felt comfortable signing a new contract. This time, the publisher offered them $150,000–an astronomical sum for the time–to work on an ambitious adventure game project. Production began in 1989, with Andy and Jason still studying hundreds of miles apart. They used every break from college to get together in Andy’s parents’ basement to discuss their respective tasks. Originally intended for release on PC and then the SEGA Master System, it was Trip Hawkins himself who suggested letting Naughty Dog get their hands on the latest development kits for the Genesis (known as the Mega Drive outside North America). So it was that, despite a long time spent getting a handle on the new hardware, not to mention the chaotic development, Rings of Power was released on the Genesis in the USA in 1991. Heavily inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Rings of Power was an isometric 3D role-playing game with turn-based combat. Criticized for its steep learning curve and complicated controls, the game nevertheless features a huge game world and a well-crafted setting. It was a successful release, with an initial run of 100,000 copies selling out within three months of release. But another Electronic Arts game released at the same time pulled the rug out from under Rings of Power, cornering both media attention and sales : Madden NFL. The release of the Genesis version resulted in a tsunami of sales, monopolizing the publisher’s production capacity and depriving Rings of Power of another production run.

In the wake of Madden NFL’s phenomenal success, Electronic Arts soon refocused its ambitions. Instead of swords, dragons, and fantasy worlds, the marketing department much preferred a pair of sneakers. A veritable parade of sports stars descended upon Electronic Arts in Redwood to promote the company’s new golden goose. The EA Sports label was founded that same year, but failed to motivate our two young developers, who instead decided to take what would turn out to be a wisely timed break. It bears repeating that at this point, Andy and Jason were still at college, and while Jason was dreaming of surfing and California, Andy had set his sights on postgraduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston.

THE 3DO ADVENTURE

With no waves in sight, Jason Rubin’s attention soon turned to a booming new technology : 3D. In 1993, he founded a new company, invested in some expensive hardware (the Silicon Graphics workstations needed for 3D special effects, costing as much as $75,000 back then), and signed an unlikely contract with Columbia Pictures to develop a fairly complex shot for Mike Nichol’s movie Wolf.

Meanwhile, in Redwood, Trip Hawkins, the charismatic leader of Electronic Arts, was working on a brand new, ambitious console. He sold his company so that he could found another that was entirely dedicated to developing this new console, the 3DO. The 3DO was built using standard architecture that was available to several manufacturers (the first 3DO was sold by Panasonic, then Sanyo, Saab Electric, and Goldstar). Riding the very recent wave of multimedia, the 3DO vaunted its built-in CD-ROM drive, its 3D processing, and its huge potential for video. The technology was comparable to that seen one year later on the SEGA Saturn and Sony PlayStation, but the 3DO needed games if its May 1993 US launch was to be a success.

So, before Jason Rubin had even started working on Wolf, the telephone rang. Citing Naughty Dog’s proven track record for quality productions–and outlining some very appealing financial rewards–Hawkins offered Jason and Andy an opportunity to come back into the fold and develop a game for his new console. They wasted no time signing the contract in light of the benefits it promised. But to guarantee total artistic independence, our two developers decided to work on the most popular genre of the day. Street Fighter II had revolutionized the video game industry when it was released in 1992. That same year, Mortal Kombat was a smash hit, and youngsters all over America rushed to the arcades in droves to let the fists and combos fly. What was needed, then, was an ambitious fighting game to showcase the 3DO’s release.

Development of Way of the Warrior began in late 1993. It proved to be an even more outrageous version of the already extreme Mortal Kombat (Midway), combining–sometimes improbably–fights between digitalized characters, uninhibited humor, and ostentatious violence. To complete the game’s development, Jason moved into Andy’s student dorm in Boston, where they hired friends, roommates, students, and family to get each creative stage of development over the line. The fighters’ images were motion-captured against a sheet hanging from the apartment wall, the outfits were made from McDonald’s Happy Meal packaging, and Jason and Andy themselves played two of the fighters. All of this quickly drained the duo’s bank account, and they were forced to rely on instant noodles for sustenance.

Without yet having found a publisher for Way of the Warrior, Andy and Jason used the last of their money to hire a few square feet at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in January 1994. On the 3DO stand, hidden among several different uninspired multimedia projects, Naughty Dog’s game was generally well received. Three publishers rushed in with offers to buy their new game : Crystal Dynamics, Universal, and Trip Hawkins himself, but the most enticing offer ultimately came from Universal. The contract gave Naughty Dog 18 months to finish their game, followed by exclusive rights for three more games, all with complete artistic freedom.

REINVENTING PLATFORM GAMES

Way of the Warrior was finally released in mid-1995. The quality of the finished game was pretty average overall and it received lukewarm reviews, but it generated solid sales despite this. Andy dropped out of college, and the duo crossed the United States to California, not far from Universal’s head office. For their next projects, Andy and Jason knew that they could no longer go it alone. The experience of Way of the Warrior’s chaotic development drove them to hire two new staff. This was how Dave Baggett, a developer, and Taylor Kurosaki, a graphic designer specializing in special effects for TV, came to be the studio’s first two hires. With the core team in place, they now needed to settle on a concept and begin the development of a new game, and an idea soon began to take shape with the announcement of a brand new console.

1 https://www.ign.com/articles/2013/10/04/rising-to-greatness-the-history-of-naughty-dog

CHAPTER TWO :FROM MARSUPIALS TO MONGOOSES

“There is nothing wrong with change, if it is in the right direction…”

Winston Churchill

iT was in Las Vegas once again, at the 1995 CES, that the story of Naughty Dog would reach a decisive turning point. The presentation of Ridge Racer (Namco) for the PlayStation, a new console that was scheduled to hit the shelves in American stores that September, came as a body blow to the newly formed team. But just as they did with Way of the Warrior, Naughty Dog naturally began to study the hottest trends of the moment, before settling on a genre that was very much in fashion : platformers. Their aim was to elevate the genre by harnessing the power of the latest consoles to their advantage and of the new era they ushered in : 3D.

The initial concept for Crash Bandicoot could be summed up in a single sentence : “What would Donkey Kong Country be like in 3D ?” Fully aware of their inexperience with this new technology, and the design of open worlds in particular, Crash Bandicoot was conceived as the natural evolution of the platform games that had delighted the previous generation (with Mario and Sonic at the top of the list), while retaining linear progression. This approach earned it the colorful codename of Sonic’s Ass Game. While SEGA and Nintendo already had their mascots in place to support the line-up for their respective consoles, Sony, as the fresh challenger, was desperately searching for a strong personality that could represent the PlayStation brand in the eyes of the public. And so was born Willy Wombat who, based on an initial idea from Dave Baggett, would be renamed Crash Wombat before finally emerging as the Crash Bandicoot we know and love, the result of an improbable combination of influences in the form of Donkey Kong Country and the Looney Tunes cartoons.

As they scrambled to find a mascot, it was love at first sight when the decisionmakers at Sony met Crash Bandicoot, all the more so as they were under immense pressure to unveil striking projects at the upcoming E3 (Electronic Entertainment Expo), which was due to be held in Los Angeles just over three months later. Sony immediately propelled Crash Bandicoot to front and center of the line-up for its new console, ready to compete with Shigeru Miyamoto’s Super Mario 64 and Yuju Naka’s Nights into Dreams. This represented a giant leap, one that was almost unthinkable for a small studio with four staff and a hitherto niche reputation.

The hotly anticipated clash between the three games–Mario, Nights, and Crash–came at E3 in 1995. While SEGA opted for a literal translation of their 2D game’s gameplay by constraining players to a single axis, Mario 64 served up a considerably more spectacular, even revolutionary vision, by giving players the freedom to roam as they please. Crash Bandicoot was a perfect fusion of these two approaches, featuring movement on several axes within linear levels set on rails. Naughty Dog, fully aware of its own limitations in terms of both technique and resources, would remedy its game’s relative lack of ambition by giving as much polish as possible to other aspects of the game. And that effort paid off. Visually, Crash Bandicoot made a big impression and immediately won over the public. Thanks to its solid game design and polished production, its never-before-seen lighting effects, and varied sequences with perfect pacing, not to mention its intuitive controls, Crash Bandicoot was an immediate sensation. Andy and Jason quickly realized that they had just conceptualized what would become their philosophy when making games : delivering immediate fun.

Crash Bandicoot was released in the USA on August 31, 1996, and was a smash hit. In just a few months, it sold more than 2 million copies worldwide to become the PlayStation’s #8 top-selling title. It was such a success that Crash Bandicoot became the first Western franchise to break into the protectionist Japanese market. Buoyed by this success, Naughty Dog was now able to establish new rules with both Universal, its publisher, and Sony, its distributor. Mark Cerny (Vice-President of Universal Interactive, producer of Crash Bandicoot and future architect of the PlayStation 4) joined the ranks at Naughty Dog, whose team had ballooned to almost 20 staff to work on the inevitable sequel, Crash Bandicoot 2.

Crash Bandicoot 2 : Cortex Strikes Back was released on October 31, 1997, in the USA. That meant one year of production in which to establish the concept, break from the game’s linear design, and implement game design choices that couldn’t make it into the first game, like camera controls. That year also enabled the studio to poach some talent from its competitors, as they did with Erick Pangilinan, who would become artistic director on The Last of Us years later. He came to the studio for his interview one early evening in 1997. The world he discovered there was the polar opposite of what he’d seen in the industry so far. The office carpet had been ravaged by pizza and wrappers from hamburgers tossed to the studio’s own mascot, an actual dog. The overall atmosphere was far removed from that seen in other companies, characterized by music and shouting. But the thing that struck Pangilinan most was the voracious passion that drove every employee at Naughty Dog, whom he saw as a group of upstart students all working towards a common goal. The studio described its mentality as that of a small team in which every employee played an important role and could influence every stage of their games’ development.

The initial contract signed with Universal demanded the production of three games, but Naughty Dog ended up developing four at a sustained pace. Crash Bandicoot 3 : Warped was released on the PlayStation in North America in 1998. The critical response was almost unanimous in lauding the constant reinvention of the series that took the original concept and ran with it. The game was once again a success, and yet again the quality of the graphics and audio along with the flexible controls meant that Crash could seduce an ever-wider audience.

For the production of Crash Team Racing, the fourth game in the franchise, the studio decided to free itself from Universal. The anthropomorphized Crash was now a globally recognized mascot–he could be seen everywhere from Pizza Hut boxes to the Eurostar–but Universal was no longer as effective in promoting the franchise. Sony bought the rights and Naughty Dog decided to self-fund most of its racer. On September 30, 1999, Crash Team Racing hit American stores and proved popular yet again with both gamers and the press. The game provided an unexpected alternative to Nintendo’s Mario Kart, which then reigned supreme, bringing some welcome subtleties to the gameplay and providing a fine swan song for the PlayStation.

ACQUIRED BY SONY

The new millennium, though, ushered in a turbulent period for Naughty Dog. The development of Crash Team Racing was extremely complex in technical terms, and the studio was subjected to ever-greater pressure from Sony, who wanted a new mascot to accompany the launch of its new console, the PlayStation 2. For the very first time, Andy Gavin thought about selling his shares in the company and taking a break from the frantic pace of work that was the norm in the industry. The video game market was rapidly evolving, and the next generation of games would require significantly larger teams. Indeed, the budget needed for the next Naughty Dog game would stand at almost $14 million. Andy was worried that he would lose the sense of carefree freedom he held so dear. However, there was no way the studio could continue on its path without significant financial backing.

It was while presenting their new “Project Y” (which would later become Jak and Daxter : The Precursor Legacy) to the bigwigs at Sony that the sale of the studio was definitively signed. In January 2001, Naughty Dog officially became the property of the Japanese manufacturer, with Andy and Jason remaining co-presidents. Gone was their independence, but as the relationship with Sony had never been anything other than positive, the developers from Virginia had no regrets about signing an agreement that would prove to be extremely profitable for Sony. Naughty Dog would keep releasing games of a consistently higher quality, without their management style or the studio’s creative freedom ever being called into question. On such an incredibly versatile market, not many developers could say the same.

YET ANOTHER VIRTUAL DUO…

The concept for the studio’s next franchise, “Project Y,” was broadly in the same vein as Crash Bandicoot : a platformer set in a colorful world. However, because the technical specifications of the upcoming PlayStation 2 still seemed to fall short of what the developers at the studio–who had adopted the nickname “the Dogs”–expected, they would not be aiming at photorealistic graphics for the game. This time, inspired by Mario 64, Naughty Dog wanted to give players the ability to explore. Initially, Project Y was led by three main figures, but it was Josh Scherr (hired in February 2001 and responsible for the cutscenes in the first three Uncharted games), who was responsible for the final character design, as well as the names bestowed on the two protagonists : Jak, the hero, and Daxter, the ottsel (half otter, half weasel).

It was while Crash Team Racing was still in development that Andy Gavin received the first development kits for what would later become the PS2. Sony’s hardware was complex and exotic, but it brought with it some interesting possibilities that enabled the Dogs to create–from scratch and in total independence–a proprietary programming language (GOAL) and, ultimately, a polished game engine. The engine was so powerful that the technical excellence on display in Jak and Daxter immediately distinguished it from other games released during the early years of the PS2. What Andy Gavin wanted to do was to create an open world that the characters could interact with, while maintaining the same level of polish and fluidity as that featured in the studio’s earlier releases. In the beginning, the characters were supposed to evolve as the game progressed (like Tamagotchi), but this idea was dropped so that the developers could focus on the very essence of the game : its gameplay and narration. To serve up a seamless gaming experience to players, a logical decision was imposed on the developers : no loading screens. It was a feature that set a precedent for the studio’s future games.

To pull off such a feat, given that the PS2 was a radically different console from earlier hardware configurations, Gavin’s technical decisions would be the fruit of an uncommon ability to improvise. Indeed, some of the components built into the console were only there to emulate PS1 games (to facilitate backward compatibility). This inspired Gavin to develop a 3D engine that ran certain processes on the processor provided for backward compatibility with the PS1, in addition to the PS2’s own processing power ! The result, GOAL, was a hybrid engine that straddled two generations of consoles and produced amazing results on the screen. Jason Rubin, meanwhile, remained frustrated that he had been unable to fulfill his narrative dreams on the earlier generation of consoles. But the power delivered by this new hardware enabled him to turn the player experience into an odyssey through a credible, coherent, and living world. At long last, technological constraints no longer seemed to be an obstacle to the imagination of the two developers, and they would now be able to make their dreams a reality : telling a story through a game.

The challenge, however, encompassed far more than just the narrative. He needed to demonstrate a skill that very few developers had mastered in the early 2000s : directing. Jason was disappointed by the first tests using the Jak and Daxter prototype, finding the animations too “video-game-y.” The character movements were too sensitive to the DualShock controls (the PS2 controller), and the dialogue scenes were basically a camera switching between characters as they spoke. It was then that Josh Scherr and Evan Wells (a developer who would go on to become co-president of Naughty Dog) came up with the idea of forcing the team to throw all current video customs and conventions out of the window. Together, they would redefine the fundamentals of stage direction : shot/reverse shot, axial symmetry, new camera angles… Drawing inspiration from real-world filming techniques, in Jak and Daxter they wanted to make a game that offered players total immersion. Despite the many difficulties encountered throughout the development process, which took a total of three years and threatened the game’s pre-Christmas 2001 release date, the team decided to deliver the completed game five weeks late, so that they could give it an irreproachable level of finish. The Precursor Bot, the game’s final boss, was finished in a rush, being completed barely 48 hours before the game shipped.

Jak and Daxter : The Precursor Legacy was released on December 3, 2001, in the United States. The threshold of one million copies sold was quickly exceeded, an amazing feat for the time. The press lauded the game’s creativity, innovation, and attention to detail. Relishing this reaction, Sony wasted no time in showcasing the two mascots, who won Original Game Character of the Year at the 2002 Game Developers Choice Awards. After a short break, development of Jak II began almost immediately, and once again Scherr imposed his “cinematic” vision of stage direction, stressing just how important it was to stand out from the competition. Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto III came out at the same time as The Precursor Legacy, a tsunami that left a lasting mark on the video game industry. Scherr convinced the whole team that Jak II could hold its own against all comers, as long as they worked hard on its universe and narrative. The level of challenge and simple fun were no longer enough to keep players going level after level : they needed to want to find out what happens next in the plot.

To elicit this desire, the game needed to be designed like a movie, like a real adventure. The traditional formula of playable sequences alternating with cutscenes had to go. The game had to be a cohesive whole and a totally seamless experience for gamers, so that they could feel immersed in the story and invested in what happens to the main characters. This would be Naughty Dog’s new mantra : an engrossing adventure and strong, likable characters, all in the service of an entertaining end result with a firm focus on what was fun. Jak II was released on October 14, 2003, in the USA and, in a first for the studio, received a cool reception. The game was attacked for being far too hard, despite its many undeniable qualities, like the feeling of freedom and the polished narrative. In Japan, the game was a resounding flop, with players moaning about its portrayal of the darker side of the heroes’ adventure.

Jason Rubin, though, was determined to make the Jak and Daxter universe more mature, in line with the tastes of an aging American audience. For the final installment in the trilogy, Jak 3 gradually reversed the roles, with the game more than ever resembling a third-person shooter with a platform gloss. The game also allowed players to get around in a buggy, and the developers later admitted that they were directly inspired by the titles from Rockstar Games. Jak 3 hit stores in the United States on November 9, 2004, and only just recuperated its $10 million budget, despite receiving positive reviews for its solid narrative and once again flamboyant production values. The results, however, spoke for themselves : fewer than two million copies sold over the course of a year, just over half of the sales achieved by the last game.

ACCEPTING CHANGE, BUT RETAINING THE FOUNDATION

By this point, Andy and Jason had been feeling tired and somewhat weary of running the endless marathon that began with the release of the first Crash Bandicoot game. They developed one game after another as the market evolved, the competition became more heated, and Naughty Dog just kept growing. However, the studio’s unorthodox structure did provide some relative flexibility to its various staff. Indeed, Naughty Dog boasted a “horizontal” management structure, with management stepping aside in favor of individual ideas and initiatives. The objective, schedule, and budget were set at the launch of each project, but then every team and every employee were given free rein to their creativity in what could be an anarchic setup. Then came the crunch, those temporal anomalies during which every single employee was working flat out day and night, weekdays and weekends, to refine the gameplay, fix bugs, and polish the end product. This way of working was great for individual labors of love, and it also enabled two staff to blaze to the forefront.

Evan Wells was already an industry veteran. He got into the video game world through the back door with a summer job working on ToeJam and Earl in Panic on Funkotron, a platform game for the SEGA Genesis. But he really earned his stripes at Crystal Dynamics, working on Gex, another platformer developed for the 3DO in 1995. It was during this time (when Gex was being ported onto the PS1 in 1996) that he saw the first screenshots from Crash Bandicoot. Impressed by the technical expertise displayed by the Dogs’ game, Wells jumped at his first opportunity to join the studio. Joining Naughty Dog in 1998, he worked as just another programmer on Crash Bandicoot 3 : Warped, and then joined the development of Crash Team Racing. He graduated to game designer for the Jak and Daxter trilogy. Strongly influenced by cinema, he taught classes at the USC School of Cinematic Arts in Los Angeles in 2001 and embodied Naughty Dog’s new direction for the Jak and Daxter series, with a greater focus on plot.

Another employee would also come to stand out from the crowd. Christophe Balestra was the studio’s token Frenchman. While still at high school in the 1990s, he was actively involved in a number of groups on the demoscene (amateur collectives who made short real-time videos that attempted to push the computers of the day to their limits) on the Atari ST. In 1997, with a handful of friends, he founded Rayland Interactive. Rayland Interactive released Mad Trax, a futuristic racer on PC, and then Bang ! Gunship Elite, an action game released on PC and the Dreamcast. Modest productions these may have been, but they enabled Balestra to learn all of the creative and technical ins and outs of game production. When Rayland wound down, Christophe Balestra moved to Toulouse where he worked at a subsidiary of Bits Studios, a British company that specialized in porting games to handheld consoles. Just a few days after joining the company, Balestra met the studio’s British director, who had come to fire all of its staff. The only one he spared was Balestra, having been impressed by the young developer’s frank attitude. It was during this time, while he was preparing a move to London, that Balestra discovered Jak and Daxter : The Precursor Legacy. He immediately applied for the first job ad posted on the Naughty Dog website and was invited for an interview the very next day. He mumbled a few words in English and answered yes to every question he was asked, but he primarily impressed through his technical expertise in low-level programming languages. Thanks to the experience he had amassed in his demoscene days, Balestra had learned how to develop as a system integrator, and he grasped the challenges of coding complex algorithms with very little processing power, skills that immediately seduced his recruiters. He moved to California in 2002 during the development of Jak II. It took the Frenchman just one week to forge a solid technical reputation within the studio, impressing even Andy Gavin himself. Despite the language barrier, Balestra’s personality earned him the nickname “Mr. No.” Indeed, he was the first to ever dare issue a categorical no to Jason Rubin when he was asked to show the results of a programming test for Jak 3.

In 2004, Andy and Jason decided to leave the company they had founded, and the transition needed to be a gentle one during the production of Jak X : Combat Racing. While Evan Wells and Stephen White were quickly earmarked as co-presidents of Naughty Dog, White couldn’t handle the pressure and opted to seize an opportunity at Sucker Punch, the studio behind the Sly Cooper and inFAMOUS franchises. Christophe Balestra was then appointed to oversee the handover alongside Wells, with both programmers being equally well respected by their peers.

Jak X, a racing game intended to conclude the Jak and Daxter series, was a fairly straightforward project that provided a bit of breathing space between two eras for Naughty Dog to consolidate its in-house structure ; with a new Sony console on the horizon, the development of a new franchise could wait. The role of Balestra and Wells was to ensure that every employee could accept these major changes, in an effort to avoid any hasty decisions and the studio’s potential closure. Jak X : Combat Racing was released on the PlayStation 2 on October 18, 2005, in the United States, and would be an epilogue for the Dogs’ franchise. Not that that would stop two more installments being released on the PSP (PlayStation Portable) : Daxter in 2006, developed by Ready at Dawn Studios (The Order : 1886) followed by Jak and Daxter : The Lost Frontier in 2009, from High Impact Games.

CHAPTER THREE : TO UNEXPLORED LANDS

“A delayed game is eventually good, but if you release a game in a bad state, you will always regret it.”

Shigeru Miyamoto

wHEN Sony announced the PlayStation 3 at E3 in Los Angeles in 2005, Naughty Dog was faced with two problems. Firstly, the GOAL engine designed in-house would not run on Sony’s upcoming console, meaning that they would need to make another from scratch, and the almost simultaneous departure of the studio’s main technical genius, Andy Gavin, would not make this process any easier. What’s more, galvanized by the studio’s success, Sony decided to break it up into two teams : the first would work on a project for the PSP, while the second would be tasked with developing a launch title worthy of the future PlayStation 3.

To resolve this technical challenge and thereby maximize the chances of getting the best out of the new PlayStation, a consortium was created that contained Sony’s first-party studios : Insomniac (Ratchet & Clank), Guerrilla (Killzone), Santa Monica (God of War), Sucker Punch (inFAMOUS) and Naughty Dog. The ICE Team (Initiative for a Common Engine) would bring together the cream of the crop from the studios in question to design an engine that would underpin their future games, all under the stewardship of Mark Cerny. This was a laudable initiative and one that was exclusive to Sony (Microsoft would struggle to emulate it for its own studios). But rather than satisfying every stakeholder with a single, complete engine, the ICE Team would ultimately produce a series of complementary tools that fell far short of the initial ambition. The main bonus for Naughty Dog, though, was to have played an active role in the PS3’s development, mastering the hardware even before its final prototype was approved. Despite it all, this period of being up in the air and the resulting lack of direction did little for the motivation of the studio’s staff, who began leaving for new ventures.

As we explained above, the first Naughty Dog team was tasked with working on a sequel to Jak and Daxter for the PSP, while the second team wanted to focus on preproduction of the studio’s next flagship series, codenamed Project Big, which would accompany the release of the PlayStation 3. Although initial feedback on the portable project was positive, the developers working on the project found it hard to get excited about. The studio’s situation, combined with the frustration felt by the team–who were some of the most technically gifted developers in the industry and who were now forced to work on a minor project–threw a wrench into the works for the new Jak and Daxter. Not even the arrival of a talented young designer by the name of Neil Druckmann managed to revive their enthusiasm. A difficult decision was then made : Naughty Dog would rather abandon the PSP project to refocus on the PS3, as the studio was not yet mature enough to handle the simultaneous development of two games. For the other team, the situation was hardly any brighter. Development of the new tools had been a disaster, and preproduction was drowning in chaos. If the decision to abandon the PSP project (which, a few years later, would become Jak and Daxter : The Lost Frontier, developed by another studio) had not been made in time, it’s highly unlikely that the Uncharted series would ever have seen the light of day. It became apparent that new blood was needed on the management team.

A NEW ERA BECKONS

After earning a degree in literature at the University of California Berkley, Amy Hennig decided to study cinema at the University of San Francisco. In 1989, it was by chance–and, first and foremost, by financial necessity–that she got her first job as a freelance artist for Atari. She worked on ElectroCop, an action game that would fail to be released. In her eyes, however, it was a revelation : video games were a media that opened up endless and as yet unexplored opportunities for her. Passionate about film since the first time she saw Star Wars : A New Hope in a movie theater in 1977, she nevertheless understood that breaking into such a male-dominated industry had more to do with luck and who you know than with any real artistic talent.

Indeed, a woman working in this industry was as incongruous as it was “suspect.” Determined, she nevertheless managed to get hired by industry giant Electronic Arts in 1991. It was two years later that she took advantage of an artistic director’s departure, filling the vacancy for Michael Jordan : Chaos in the Windy City. The game was a success, but the opportunistic shoehorning in of a star to promote the game was completely out of place. Hennig, though, used the opportunity to climb the ranks one rung at a time, becoming one of the few women to occupy a management role in the video game industry. As the 1990s drew to a close, she seized a new opportunity at Crystal Dynamics. There, she met Richard Lemarchand and Bruce Straley, who would also go on to swell the ranks at Naughty Dog. But before that, they would work together on a AAA title, Legacy of Kain : Soul Reaver (the 3D sequel to Blood Omen developed by Silicon Knights), that would be burned into the minds of gamers on the first PlayStation. Following in the footsteps of Tomb Raider–an impressive production packed with twists for its memorable characters–by making remarkable use of the game environment, Soul Reaver was a hit game and provided a launchpad for Amy Hennig’s career.

She would oversee the development of two more games (Soul Reaver 2 and Legacy of Kain : Defiance) before joining Naughty Dog, who had been courting her for some time already. She joined the Californian studio as a lowly developer in 2003, working on Jak 3. However, she would soon form part of a core team that, from 2005 onwards, would be working on a new franchise to accompany the next generation of Sony’s consoles, the famed Project BIG.

Serving as creative director at Naughty Dog for the duration of the Uncharted series, Amy Hennig, with her unique personality made up of equal parts refinement and fun, led an atypical career as a strong woman in a man’s world. From 2003 all the way through to her unexpected departure in 2014 while production of Uncharted 4 was in full swing, Amy Hennig embodied the series, imposing an unprecedented standard of quality that redefined how narrative was built into gameplay and formed the very essence of the franchise.

FALLING BY THE WAYSIDE

So it was that, while the first team was preparing to abandon production of Jak and Daxter for the PSP, the second Naughty Dog team was working flat out on a new concept under Project BIG. At its head was Amy Hennig, accompanied by Josh Scherr, Evan Wells, Neil Druckmann, and Richard Lemarchand, who had come up with an initial concept under the working title of Zero Point. The draft plot placed the action in an undersea research facility. Bio-terrorists had broken in, and it was up to a small team to do all they could to regain control and prevent an environmental disaster. The nefarious plan, dreamed up by one Navarro, involved using the undersea base to launch a poison capable of destroying all of the world’s forests. The general design of the game incorporated elements of steampunk and Victorian architecture, while the protagonist (already going by the name of Drake…) was based on Marty McFly (played by Michael J. Fox in the Back to the Future series by Robert Zemeckis). The first technical prototypes veered between photorealism and cartoon stylization, without ever settling on one or the other, and the general layout of the levels required the development of a powerful fluid mechanics engine (with most of the levels being underwater or in the process of flooding). The undersea facility featured lots of open spaces, providing plenty of opportunity for exploration. However, the technical challenge only grew when the developers dreamed up weapons that manipulated water, hand-to-hand combat between different enemies, and an autolock aiming system to rid the game of its more punishing mechanics and return the focus to the plot. A lot of puzzles were created, some even based on sound waves.

It was at this point that the Dogs glimpsed the first screenshots of an ambitious game being developed by one Ken Levine at 2K Boston. He had just revealed his latest project to the world : BioShock, characterized by opulent artistic direction, a complex game world, and mind-blowing graphics. But it was an announcement that put an end to Zero Point. Despite adopting different approaches, the two games were too similar, and Naughty Dog’s project was still at too early a stage to compete.

FORTUNE FAVORS THE BOLD

After going almost all the way back to the drawing board with Zero Point, whose initial concepts would gradually be incorporated into Uncharted : Drake’s Fortune, the bigwigs at Naughty Dog were engaging in some selfreflection. As with every new generation, the latest consoles were more demanding in terms of resources, but they also required more expertise in engineering. And as Christophe Balestra freely admitted, the studio’s programmers had begun to lag behind when it came to the technical skills needed to work with recent developments in programming languages on PC and the now widespread use of shaders (a new computing routine that managed the absorption and diffusion of light). BioShock provided the stark proof.

Ever-increasing processing power, video chips dedicated to increasingly specific tasks, and a storage capacity that had exploded with the inclusion of a Blu-ray drive on the PS3 : the developers were always on the clock, forced to understand the latest advances in computing technology, come what may, as the famous Project BIG faded into the background after Zero Point was abandoned. As Amy Hennig recalls : “The transitional period was a real nightmare [laughs]. No, really, it was very difficult. We had to start again from scratch and we couldn’t use anything we had designed up until that point on Jak and Daxter. We found ourselves with a new platform, a lot of new faces in the team, and a new concept. And like all transitions of that magnitude, it was a pretty big leap. The example that springs to mind is that before, the artists literally painted the textures onto the objects, and now they had to use shaders like the people at Pixar do. The tiniest rock needed individual attention. As did the moss growing on it. We needed to be able to manage the light, how it fell on the rock in question. We needed to make the grain of characters’ skin look realistic. And every time we needed to use successive layers of shaders. And those are just a few examples. To obtain results like that took a lot more work using far more complex techniques than in the past. And all of that work was just for the game’s visual appearance ! Then we also had to work on the gameplay proper. In short, it was a real challenge but the best in the industry like tackling challenges like that. It’s interesting when you have to relearn everything, and people who don’t like change don’t last very long in the video game industry.”1